Table 6.1 Financial performance of individual business units within Amsterdam airport

Jaap de Wit

When the discussion in the Netherlands about the viability of an offshore airport in the North Sea finally came to an end, the Dutch cabinet decided in 1999 to resume preparations for the privatisation of Amsterdam airport Schiphol. These preparations had already been started in 1995, at the request of the Dutch parliament, but they had been postponed for a few years to give society full opportunity to arrive at the conclusion that the existing location of the national airport will do for another few decades. During the years 2000-2002, the details for an Initial Public Offering (IPO) of Amsterdam airport were further elaborated. After a period of political turmoil, a decision in parliament is now expected to be forthcoming in 2004.

In general, the major driving forces behind airport governance reform are adequately described elsewhere (cf. Ashford and Moores, 1999; Carney and Mew, 2003; and Graham, 2001). Political considerations in the Netherlands concerning privatisation of Amsterdam airport primarily focused on the argument that public ownership should not be continued if it is not indispensable for safeguarding public interests. In other words, if public policy measures effectively cover these interests, these measures should be preferred to private ownership. This appears to be the more urgent since, these days, the state, as a shareholder, is left with very little influence in the limited company that is Amsterdam airport.1

During the preparations for privatisation three public interest issues were identified that require adequate legal ruling:

A new legal framework for noise measurement as well as noise and safety contours has been put in place recently, and therefore the further preparations concentrated on the two other interests. Here we discuss primarily the development of a regulatory framework for the airport charges.

The choice between a more heavy-handed and a light-handed regulatory system is mainly determined by the deemed monopoly power of the airport involved. This depends on the relevant markets in which the airport provides services. We successively discuss here the market delineation of Amsterdam airport services and the related question of airport competition, the controversy between single, 'middle' and dual till, and negotiated access principles. Finally, we analyse the instruments that have been developed to guarantee the availability of a well-equipped national airport.2

Starkie (2002) clearly articulates that the raison d'ȇtre of economic regulation is to try to encourage the 'natural monopolist' to be cost efficient and to increase output to a level that maximises economic welfare. Conventional wisdom views the airports as an example of a natural monopoly industry.

This issue played an important role in the development of a regulatory framework for Amsterdam airport. In an early stage of the preparations for the new framework, the Dutch Competition Authority (NMa) was requested to review the then current airport charges in the context of the general competition law. The NMa (2001) concluded in its answer that Amsterdam airport is a monopolist in the relevant geographical market, which was restricted by the NMa to the Schiphol airport area.3 To arrive at this conclusion, the NMa more or less ignored the characteristics of the relevant product market. The main criterion used to define the relevant product market is demand substitutability, if we follow the definition proposed by the European Commission (Larouche, 2000). This brings us to the question as to who is the airport's customer? The identification of the customers of the airport services is not so obvious, because an airport operates mainly upstream in the supply-chain. Consequently, a multi-stage approach is required that places the demand for airport services at Amsterdam airport in the context of the substitution possibilities throughout the supply-chain, as Frontier Economics (2000) reported to the NMa. It is not only the demand from airline operators that is relevant here. This demand ultimately derives from passengers and cargo shippers. Substitutability in the context of the SSNIP-test approach4 has to be analysed in relation to the demand behaviour of (categories of) airline operators, (categories of) passengers and cargo users at Amsterdam airport. This may imply more segmented product markets for airport services of Amsterdam airport than was assumed by the NMa. Before analysing the relevant markets in more detail, we first have to address the question which products are provided by an airport and which customers are involved. The next question is whether the supply of (a subset of) these products at Amsterdam airport is a natural monopoly.

An airport nowadays is a multi-product firm that provides a growing range of services and products to an increasing number of customers.5 ' Actually, the growing customer base of larger airports is one of the attractive characteristics to private investors. Real estate developments (hotels, restaurants, business centres, landside shopping malls, etc) at the airport site and in the neighbouring region focus on an increasing variety of customers. Selling duty free articles to the air travellers has become an important profit generator. Car parking lots are operated for visitors and travellers. Cargo sheds are provided to cargo handling companies and forwarders.

Irrespective of this increasing diversity of products and customers, the essential role of an airport remains the interface between the air transport mode and surface transport modes.

This primarily boils down to the accommodation of aircraft movements, i.e. services for safe landings, take-offs, taxiing and parking of aircraft, and the throughput of passengers, baggage and cargo via this multi-modal interface. These core activities are also the airport services that have to be taken into account within the context of market power. Hotels, car parking shopping malls etc may benefit from a locational rent at the airport site, but these services actually compete with comparable services downtown or in the wider airport region.

Runways and terminals, however, cannot be duplicated m the same area by a competing new entrant. We therefore focus on the prices of these airport services, i.e. landing and take-off charges for aircraft movements, aircraft parking charges, passenger charges for the terminal throughput6 of passengers and baggage.7

Although the concept of the natural monopoly may well apply to the network component of most network industries (gas, electricity, water, railroads etc), it can be questioned whether this is the case for airports. A natural monopoly requires the firm's cost function to be subadditive over the entire range of outputs. Actually, this is quite a demanding condition, since we have to determine whether single-firm production of y is cheaper than its production by any combination of smaller firms. That is, we must know C(y*) for every y* ≤ y (Baumol et al, 1982). This requires a constantly decreasing long-run average cost curve. For airports however, this characteristic is unlikely. Doganis (1992), for example, indicates that, beyond a level of about three million passengers, unit costs flatten out and do not seem to vary much with airport size. As pointed out by Starkie (2002), it is even more likely that the cost curve will increase for larger airports, due to the increasing scarcity of one input factor, i.e. land in the neighbouring area of the airport. Thus, competitive entry is not frustrated by returns to scale but rather by other entry barriers, especially the availability of land. Also, other factors may stimulate the airport's market power, such as the lock-in effects for airline operators. This will be addressed in the analysis of relevant markets for airport services of Amsterdam airport.

If we apply the multi-stage approach to the various customers in the supplychain, the primary customers are the airline operators.

An airport's market power is reflected in the level of captivity of the various airline operators at that airport. Captivity is created by entry and exit barriers. If the airport is the home base of a carrier, sunk costs will be involved in operational facilities, buildings, maintenance, etc. Branding of the airport with the national airline also creates exit barriers. These sunk costs make it costly to station aircraft at other airports if the home-based operator increases the airport charges. The reluctance of Dutch charter airlines to station aircraft at the regional airports in the Netherlands is partly explained by this operational argument. They prefer to serve these regional markets by so-called "W-flights" from Schiphol.

Another argument put forward to illustrate the airline's captivity refers to the slot scarcity at alternative airports. This argument however has a limited impact. First, slot availability varies strongly between airports. Secondly, a limited reallocation of flights can already be an effective demand reaction if the airport operator raises its charges above competitive levels (see Greenhut et al, 1987).

The regulation of international air transport markets also stimulates captivity. In particular, older types of bilateral air service agreements specify the routes to be served by the designated carrier. As a consequence, KLM is obliged to operate from Amsterdam airport to benefit from a number of Air Servive Agreements (ASA). This captivity has further increased due to the fact that the third and fourth freedom traffic rights based on ASAs have been combined with sixth freedom operations via the home base Schiphol during the last 25 years. This has resulted in a large number of transfer passengers via the home base. This connectivity got an extra boost by the intensified hubbing process after the liberalisation of the internal market in 1993. Nowadays, KLM's radial network heavily depends on transfer passengers (probably more than 70%) and, as a consequence, the transfer share in the total traffic volume of Amsterdam airport is also quite substantial (about 40-45%). If, however, Schiphol airport increases its charges, KLM could not respond adequately. A reallocation of flights to other airports would more than proportionally damage the KLM network synergy.8 Consequently, KLM is a captive customer at Amsterdam airport due to aeropolitical as well as operational conditions.

One should realize, however, that this situation can rapidly change. Since KLM has been taken over by Air France, the captivity will decrease.9 In that case, an increase in airport charges might evoke a reallocation of flights from Amsterdam to Paris, using the high-speed rail link Amsterdam-Paris as a feeder line.

For the time being, captivity of airline operators at Amsterdam airport strongly depends on the type of carrier: KLM's captivity was high but is decreasing, whereas the captivity level of the home-based charter airlines and short-haul foreign airlines is lower. Long-haul foreign airlines and cargo airline operators probably show the lowest level of captivity. Both types of carriers can easily choose a different large airport as their hub to serve Europe if aeronautical charges become relatively too high.10

It is still premature to conclude definitely on the market power of Amsterdam airport based on these levels of captivity, which is what the NMa (2001) did. Such a conclusion requires a further analysis of the final stage in the supply-chain. The ability of Amsterdam airport to raise charges for its services to airlines ultimately depends on the willingness of the passengers (and cargo users) to pay for air transport services to and from Schiphol.11 This willingness to pay is ultimately determined by the substitution possibilities in terms of alternative airports or transport modes.

Since, in general, the nature of transport demand is conditioned by the origin and destination of the trip, the individual route in air transport is also the starting point for the relevant product market.12In other words, in principle, route A-B is not a substitute for route C-D. Even a further segmentation should not be surprising within this narrow definition. The reason is that the criterion of demand substitutability implies that the same physical product (a transport service for route A-B) can be supplied in different relevant product markets, if two or more distinct classes of customers whose preferences differ buy it. For example, the differences in time- and price-elasticity between business and leisure passengers may require a split into two distinct relevant product markets within route A-B.

The body of case law on relevant markets as developed under the European Commission's legislation not only points towards more segmentation and fragmentation of relevant product markets for airport services. More aggregate relevant product markets can be found as well (Larouche, 2000). For example, indirect transfer flights A-H-B via each relevant hub H have to be included in the A-B market of direct flights.13 Furthermore, high-speed trains can be included in the A-B market if they are an adequate substitute in the eyes of the customer (Paris-London, Paris-Brussels, London-Brussels).

Mediterranean holiday-package tours are another example of a more aggregate relevant market. According to the Commission, these trips are sufficiently substitutable from the demand side to include them in the same relevant market.14 In this view, many Mediterranean airports compete in the holiday package-tour market.

It is similar for air cargo. In the eyes of the Commission, the relevant market for airport services in intercontinental air-cargo transport comprises many airports on the same continent, since indirect routes as well as multi-modal transport chains are now taken into consideration.15 Consequently, many West European airports are potential competitors of Amsterdam airport in the relevant product market for air cargo.

As already indicated, other relevant product markets based on the principle of demand substitutability are the indirect routes A-H-B in the city-pair market A-B. In intercontinental city-pair markets the relevant product market can also comprise hubs in the other continent. For example, in the Warsaw-Detroit market not only Amsterdam and Frankfurt are competing hubs but possibly also New York. From the point of view of demand substitutability, these indirect markets are competitive, and the level of competition as reflected in the cross elasticities depends on the number of alternative indirect routes and the number of carriers serving these routes. The share of these indirect transfer markets in the passenger volume of Amsterdam airport is substantial: 40-45% of total passengers. This concerns non-captive product markets since most of these passengers can choose between different indirect routes and their intermediate hubs.

In 1997, the Commission included the following airports as competitors in the West-European transfer market: Frankfurt, Munich, Copenhagen, London, Amsterdam, Brussels, Paris, Zurich and Vienna. Perhaps today Milan Malpensa should also be included, whereas Brussels and Zurich should be excluded.

The NMa's opinion on the role of Amsterdam airport in this category of relevant product markets is peculiar. The exclusive concentration on supply-side (non)substitutability brings the NMa (2000) to the conclusion that competition in these markets only exists in theory, based on the argument that airlines in Europe cannot easily move their operations to another hub. Apparently, this approach enables the NMa to ignore fully the increasing probability that the price-sensitive transfer passengers will choose other hub airports and other carriers if aeronautical charges substantially increase.16

All in all, Starkie (2002) concludes that the market power of an airport with respect to its aeronautical charges is likely to vary between the different relevant product markets. As Starkie also illustrates, the final conclusions about monopoly power of airports also require a further analysis of the spatial setting of each relevant product market. This is about catchment areas and the availability of proximate airports as sufficient substitutes to the passenger: the relevant geographical markets.

It is not unusual to apply the distance to the airport as a simplification to determine the radius of the catchment area.17 Within the overlapping part of the various circular catchment areas, the airports involved are expected to compete.18 This may, however, result in an oversimplification of one variable, i.e. distance. Airport-choice models can be more helpful to delineate relevant geographical markets for airports. Important variables in these models for example as developed by Harvey (1987), Ashford et al. (1987), Furuichi and Koppelman (1994) and Veldhuis and Pelger (2003), are the airline ticket prices offered in the relevant product market at each competing airport, and the various travel times in the transport chain, especially access time and flight frequencies. In each separate product market the demand elasticities of these variables can vary substantially. Long-haul flight passengers show smaller elasticities with respect to travel time than do short-haul passengers. Business passengers show higher elasticities as to travel time and lower elasticities as to airline ticket prices than do leisure passengers.

It is also important to realise the impact of trade-offs between these variables. A cheap airline ticket will compensate for longer access times. Regional airports, for example, that accommodate low-cost carriers, are covering much larger catchment areas with respect to the air routes served. In addition, higher flight frequencies compensate for longer access times. For example, in 1995, about 40% of the airline passengers from the Rotterdam region to London were captured by Amsterdam airport instead of being served by Rotterdam airport (De Wit, 1996). Differences in flight frequencies and more competitive airline ticket prices explain this airport choice.

Obviously, changes in the aeronautical charges are expressed in the ticket prices. The more expensive the airport, the smaller the catchment areas for the various relevant product markets owing to higher ticket prices. The popularity of more distant cheap airports served by low cost carriers provides further evidence of this point.

It is important to realize that a catchment area analysis is a snapshot situation. The delineation of geographical relevant markets can rapidly change over time. For example, access times may change due to new infrastructure. The high-speed rail link Amsterdam-Brussels will relocate an important part of the Belgian market into the overlapping catchment areas of Paris and Amsterdam airports. At the same time, the catchment area of Amsterdam airport may further shrink due to diminishing accessibility by road and rail as a consequence of increasing congestion and decreased rail punctuality.

It is obvious that the captivity of passengers will increase with decreasing distance between the place of origin in the catchment area and the airport. If the highest population density is found in the proximity of the airport, the major part of the originating passengers will be generated from this limited area. As a matter of fact, 70% of Amsterdam airport's non-transfer passengers originate from the three surrounding provinces (North Holland, South Holland and Utrecht). It is likely that a relatively low percentage of airline passengers from this area would choose a different airport. Outside this core of the catchment area the average captivity will diminish and the percentage of passengers that choose a competing airport will increase.19 Apparently, the border provinces belong to the overlapping part of different catchment areas of various competing airports. These border provinces show a lower population density and a lower propensity to fly than do the three core provinces. As a consequence, only a relatively small share of Amsterdam airport's total non-transfer passenger volume originates from these border provinces. However, this small share of non- or less- captive passengers in the catchment area does not confirm in advance the market power of Amsterdam airport in the various geographical relevant markets. Starkie's (2002) reference to Greenhut et al (1987) is highly relevant here: competition at the boundary points is often sufficient to transmit price changes over the whole of the market. This is also illustrated by the fact that Amsterdam airport recently (2002) became more anxious about this part of market.

The analysis of the relevant geographical markets of Amsterdam airport indicates that demand substitutability of airport services at Amsterdam airport can be based on overlapping catchment areas of other European airports. The number of competing airports and the level of competition depends on the individual relevant product market.

Based on these findings, we conclude that a light-handed regulatory regime for the aeronautical charges of Schiphol airport would be the most obvious solution, if any regulatory regime should be introduced. The conclusions of the NMa (2001) on the monopoly power of Amsterdam airport pointed in a different direction. This probably at least partly explains the rather heavy-handed regulatory framework that has been developed.

The aeronautical charges of all international airports in the Netherlands have been subject to a legal approval procedure of the Minister of Transport for many years. The authorities originally intended to implement the non-discrimination article 15 of the Chicago Convention through this approval procedure. In this Convention, contracting states agreed not to apply discriminatory aeronautical charges to foreign versus national aircraft. This origin of the approval procedure in the Netherlands explains why even very small general aviation airstrips were subject to this procedure: very small aircraft from abroad could land and take-off at them and might be discriminated by the airport charges. To underline the general interest of this procedure, each approval is still crowned by a Royal Decree.20

This procedure was also developed to comply with other international obligations, such as various ASAs, which usually require that the airport charges reflect the principles on user charges recommended by ICAO. These principles broadly refer to cost-relatedness, transparency and non-discrimination.

In the second half of the 1990s the procedure descnbed came under pressure. The explanation is obvious, since the only reason for this procedure was to prevent possible discrimination between aircraft of different states. Furthermore, the criteria for approval were vague. The tension between airport users and airport operators built up, especially at Amsterdam airport and the larger regional airports of Eelde, Rotterdam and Maastricht. This can be attributed partly to the absence of rules concerning a consultation procedure and the information to be provided by the airport operator to the users. The basic explanation for this tension, however, was the increased competition in the liberalised internal air-transport market, which forced airlines to implement continuous cost reduction programmes. At the same time, Amsterdam airport continued to increase the aeronautical charges and succeeded in staying profitable by expanding its commercial activities.

In 1998, Dutch competition law was implemented, together with the establishment of the new competition authority NMa. Airline complaints about airport charges increasingly started to point towards the abuse of monopoly power. This was followed by several court cases in which the state was accused of approving alleged abuse of monopoly power by the airport. It was obvious that this procedure required a fundamental revision. When, at the end of 1999, the Dutch minister of transport decided to resume the preparations for the privatisation for Amsterdam airport, the efficiency of the airport services market of Amsterdam airport was identified as a public interest that should be safeguarded by new procedures before actual privatisation could take place. The NMa (2001) report further underlined the importance to replace the existing approval procedure by explicit regulation, in order to cope with the alleged monopoly power.

The experience with the introduction of new regulatory regimes in other network industries inspired the Ministry of Economic Affairs21 to introduce the so-called negotiated access model as a new component in the regulatory regime on aeronautical charges at Amsterdam airport (Ministry of Economic Affairs, 1999). Network industries like gas, water, electricity, telecommunications and railroads have been involved in a process of vertical separation in recent years to isolate the monopoly component (the network infrastructure) from the competitive component (the service providers). In such a situation, network access is conditional to create competition between service providers.

This access can be realised either in a relatively light-handed or in a heavy-handed approach. In a so-called negotiated (third party) access approach (Engel, 2002), only minimum network access conditions are specified ex ante. Market parties themselves determine the tariffs for the use of the network and disputes are settled in court.

The regulated (third party) access approach is more heavy-handed (Bier, 2001). The public authorities influence the tariffs directly, via either a price cap or a rate of return regulation. Access conditions are determined ex ante and disputes are primarily settled by the regulator.

One may wonder, however, whether market access to the network infrastructure should be the key issue in the regulation of airport services. In air transport, the issue of market access has been regulated for many years already in an international setting. Bilateral air service agreements between states or EU competition rules for the internal market explicitly address the issue of market access. Congested EU airports can be earmarked as slot-coordinated airports based on objective criteria. For these airports, slot scarcity is regulated by uniform EU slot allocation rules. These rules explicitly address the interests of new entrants by the creation of a separate slots pool. 22

All in all, the history of the air transport industry is different from other network industries in that it has operated in a strictly vertically integrated way for a long time. It justifies the conclusion that market access should not require much attention in a new regulatory framework for Amsterdam airport. The basic idea of the negotiated access model corresponds with the findings from the relevant market analysis for Amsterdam airport: a light-handed regulatory model without direct regulatory interference in the tariffs.

However, the regulatory system that was ultimately developed for Amsterdam airport only bears the name 'negotiated access'; in actual reality it became a full-fledged regulated access system. The tariffs and conditions are not primarily negotiated by the market parties but almost completely fixed ex ante by detailed rules. For example:

The resulting detailed regulation is partly based on ex ante rules and partly on ex post procedures. However, the details do not correspond with the negotiated access model concept. Irrespective of this confusing terminology, the main question remains unanswered: what determines the choice for a negotiated or a regulated access model? Bier (2001) has tried to derive these conditions under social welfare considerations for the electricity market. If the monopoly power of the airport appears to be moderate, the regulatory incentives should be moderate as well, keeping in mind Starkie's (2002) warning that there is a trade-off between living with imperfect regulation or imperfect markets. If the relevant market analysis and the resulting level of monopoly power of Amsterdam airport is adequately taken into account, it is obvious that the characteristics of a true negotiated access model make this approach more appropriate for the regulation of Amsterdam airport.

During the preparations for the new regulatory regime of Amsterdam airport, the single - dual till controversy also played a role. All over the world, and also in the Netherlands, airlines intuitively advocate a single till, whereas airports intuitively opt for a dual till. Airlines underline the common-good characteristics of airport activities: "runways serve to develop commercial activities" (See also footnote 5). However, airports underline the need for a reasonable rate of return on aeronautical activities and the entrepreneurial freedom to develop new commercial activities.

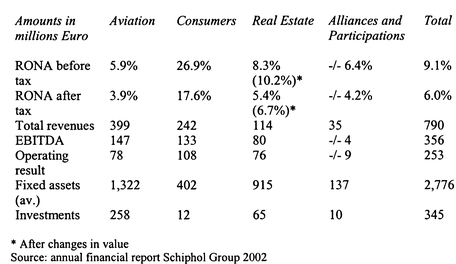

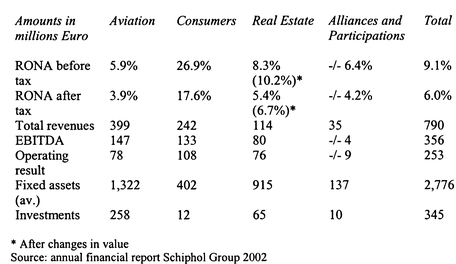

The consequences of these two approaches for the aeronautical charges are illustrated by Amsterdam airport's financial figures (2003) which are specified in four individual business units: aviation, consumers, real estate and alliances/participations. The unit "aviation" comes close to the aeronautical activities, and the other business units together more or less cover the non-aeronautical/commercial activities (see Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 Financial performance of individual business units within Amsterdam airport

According to the NMa (2001), an interval of 6.5-9.2% for the overall WACC before tax is reasonable, as is an aviation-specific WACC of 7.9%. The contrast between the consequences of a dual-till and a single-till is clear: a dual till requires a substantial increase in airport charges to boost the aviation Return On Net Assets (RONA) from 5.9 to 7.9%. A single till, however, allows for a substantial reduction in airport charges as long as the overall RONA remains in the range 6.5-9.2%.

The Dutch version of the 'till' problem is a little more complicated, however: a choice had to be made between three options. This is because in a public hearing on the privatisation of Amsterdam airport, the NMa introduced the third option of a so-called 'middle till'. The NMa arguments for this option ran as follows. Locational rents play a major role in the profits of commercial activities. These locational rents should be partly redistributed to the benefit of the airport users. Therefore, the land at the airport site and even around the airport should be included in the regulatory asset base. If this land were hired for commercial activities, the aviation till should benefit from the locational rents by applying market-oriented square-metre prices that could be derived from comparable sites elsewhere, like the Central Business District. Some considerations have to be taken into account concerning this middle till option. Forsyth (2003) for example clearly indicates that locational rents are not due to the abuse of market power like monopoly rents, which reflect market inefficiencies. Locational rents are difficult to separate from monopoly rents at an airport, but as such they arise from the premium paid for preferred locations. The better the landside accessibility of the airport region, the lower the locational rents. Not only the airport operator gets these rents. Also owners of the surrounding land enjoy these locational rents by virtue of their proximity.24

From the point of view of allocative efficiency, however, the middle till is not fundamentally different from the single till, since both of them intend to cross-subsidise the aeronautical activities. The allocative efficiency of the single till has been disputed in the case of capacity-constrained airports (CAA, 2000; Starkie and Yarrow, 2000), since it reduces the incentives for the optimal use of airport facilities. Since Amsterdam airport will remain a slot-coordinated airport after the opening of the fifth runway, slots remain scarce during substantial periods of the day. Under these circumstances, the expected economic inefficiency of a single till has resulted in the decision to implement the dual till system.

Although it can be contested whether the interest of the 'main port' availability is a public interest, it was identified as such in the preparations for the privatisation of Amsterdam airport. As a consequence, specific instruments were developed to safeguard this interest. Since there are some interrelations with the 'main port' interest and the efficient market interest, it is necessary to discuss the safeguards for this main port interest here in more detail.

Amsterdam airport was corporatised as a limited company in the early 1950s. Public ownership for a long time corresponded with the public utility interest of the airport. However, commercialisation, privatisation and internationalisation of the airport sector have been strong incentives to develop new commercial interests as an airport company. New opportunities emerged at the Schiphol site, in the wider airport region, at other Dutch airports, and abroad at foreign airports. The single public utility interest issue of a well-equipped home base for the national airline KLM is less self-evident anymore in that stage of development.

Parallel to these developments, another development was important: the disappearance of state commissioners in the supervisory board of publicly owned enterprises.25 Under these circumstances it became evident that the influence of the state as a shareholder in Amsterdam airport is not so different from the position of any other shareholder in a Dutch limited company.26 In the existing corporate governance structure, this influence is very limited nowadays.

If the state was to pass on to privatisation of Amsterdam airport, this would trigger new commercial activities, productivity improvements, higher cost efficiency, international participations, etc. However, the core business - i.e. the aeronautical activities at Schiphol - will never show high rates of return (see the table above). Politicians therefore suspected the danger that Amsterdam airport, after privatisation, would neglect its core business and put big efforts in other more profitable commercial activities.27

To cover the interest of the core business for the Dutch economy, a separate instrument is intended to be introduced; specifically, an operating licence for an unlimited period of time. If the airport operator were to neglect this interest in a substantial way, the Minister of Transport could withdraw the licence if the airport's viability is endangered. The problem is, however, that it would take years to remove the operator. In other words, the licence would be almost ineffective. To be able to change the operator immediately (if necessary), the legal ownership of the land at the airport will be transferred to the state just before the actual IPO is started. At the same time, the land is leased back to the airport operator for zero ground rent.28 Substantial negligence of the core business, to an extent that the continuity of the airport is endangered, is an explicit condition to immediately end the land lease. This land lease also enables the immediate expropriation of the infrastructure and real estate on the leased land.29 All in all, an important incentive has been created to influence the behaviour of the airport operator according to the public interest of the 'main port'.

A final comment concerns the enforcement of this licence. Enforcement criteria should be specified before the introduction of the policy measure. However, a 'well equipped airport' is not a standard concept. It will change in the course of time. To grasp the key issues in a monitoring system is difficult, and too much focus on the short run in this system could result in direct public interference with private investment policies of the airport operator. However, the regulatory principles of dual till and rate of return regulation as such are already sufficient incentives to guarantee adequate investments in the aeronautical facilities. Therefore, withdrawal criteria for the operating licence can only be seen in the context of an ultimum remedium; otherwise a combination of a heavy-handed economic regulation and an operational licence could develop into a substantial degree of regulatory overkill.

Starkie's trade-off between living with imperfect regulation or with imperfect markets will probably show whether a light-handed system based on negotiations between market parties is preferable for Amsterdam's Schiphol airport.

1 Other arguments are, for example, better access to capital markets, efficiency improvements, and a better position for Schiphol airport to participate in international airport tenders.

2In the Netherlands this is called the 'main port' interest. The question may arise, however, whether this interest actually is a public interest, i.e. a social interest for which the public authorities take the final responsibility to look after. For example, what to do if KLM and Air France decide to choose Paris as their main hub? Or, what about a high-speed rail link from Amsterdam to Brussels airport that changes Zaventem into a relevant alternative?

3 This conclusion surprisingly indicates that the NMa may have misunderstood the concept of the geographical market. The relevant geographical market does not necessarily comprise the location where the relevant services are produced and (inevitably) consumed, but it concerns the area in which the conditions of competition are sufficiently homogeneous. Therefore, for airport services, the concept of the catchment area for an airport answers much better the relevant geographical market definition.

4 The Small but Significant, Non-transitory Increase in Price (SSNIP) is the most common approach to relevant market delineation. This test should answer the question, whether the consumers of the product for which a hypothetical small (5-10%) but permanent price increase is introduced would substitute other products or other suppliers established within the same area studied. If this is the case and the substitution compensates the price increase, the substitutes and the area belong to the same relevant market.

5 An intriguing question in this context is, whether the joint production of the essential air traffic and passenger services on the one side and for example duty free sales to passengers at the other side is an example of joint production in the Marshallian sense. Are some of the production factors public inputs in the sense that once they are acquired for the use in producing one good, they are available costlessly for use in the production of others? This opinion is more or less reflected in KLM's justification for a single till by stating that the runways and terminal make duty free sales possible. It seems however more likely to assume a more flexible relationship, i.e. economies of scope and quasi public, sharable inputs.

6 Usually passenger terminals in Europe are owned and operated by the airport company. Due to the high transaction costs between the airport and the airline, home-based carriers may prefer to rent or even own dedicated piers and gates. The new Lufthansa terminal in Munich is the current exception.

7Since most cargo handlers and forwarders own or rent their cargo terminals at the ramp, the terminal costs are included in the handling and forwarder fees. This explains the absence of cargo charges in the overview of official airport user charges at most European airports.

8 Recent analysis reveals that KLM's intercontinental network is almost completely dependent on the transfer volume. If this volume is eliminated, only daily flights to New York and Paramaribo (Surinam) could be maintained.

9 Until now EU Cross-border mergers have been frustrated by the nationality clauses in ASAs. Stepwise, these regulatory obstacles are disappearing. For example, the European Court of Justice decided in November 2002 that these nationality clauses are in conflict with EU-rules on the free establishment inside the EU. Furthermore, in May 2003, the EU Transport Council agreed on the EC mandate to negotiate a multilateral ASA with the USA.

10 An exemption has to be made for the alliance partners of the home-based carrier, which are almost as captive as the home-based airline.

11 One should realise that passenger charges are directly transferred to the passenger, without further airline interference. Every flight coupon shows the amount of airport 'tax' to be paid directly by the passenger. The question whether the airline will absorb a part of these airport charges is not relevant here.

12 See also the ECJ Judgement of 11 April 1989, case 66/86, Ahmed Saeed Flugreisen v. Zentrale zur Bekampfung unlauteren Wettbewerbs (1989) ECR 803 at Rec. 40-41.

13 See for example Decision of 11 August 1999, Case COMP/JV.19, KLM/Alitalia (2000) OJ C 96/5, CELEX number 399J0019 at Rec. 22.

14 See for example the Air tours-First Choice case (Case no IV/M.1524 of 22.09.1999).

15 KLM/Alitalia, supra, note 25 at Rec. 23-25.

16 Most hub airports in Europe apply a kind of Ramsey pricing based on different levels of price elasticity in the various market segments. Transfer passenger charges are for example substantially lower (or nil) than charges for departing passengers. It is possible, however, that a difference in terminal costs is involved as well, since departing passengers use both the land- and airside of the terminal, and transfer passengers only use the airside.

17 See for example the Commission's approach: a 100 km radius around the airport for regional flights and a 300 km radius for direct intercontinental flights, in Commission Decision of 21 May 1999, Case No 1V/M.1255 - Flughafen Berlin; Commission Decision 98/190/EC of 14 January 1998, FAG-Flughafen Frankfurt/Main AG, It should be noted, however, that the Commission also points to other factors, like access mode time.

18 A misinterpretation of these EC distance standards may also have played a role in NMa's opinion on the market power of Amsterdam airport: it appeared that only those airports situated within a distance of 300 km from Schiphol have been identified as Schiphol competitors. However, these standards are about overlapping catchment areas, each of them with a radius of 300 km (Frontier Economics, 2000). Therefore, one cannot ignore Frankfurt and Paris if EC standards are applied correctly.

19 This impression was confirmed after matching the data of the passenger surveys of a number of German airports and the Schiphol passengers survey.

20 To date, Dutch citizens are informed about five times a year through official announcements in the Dutch newspapers, that it pleased Her Majesty to approve the new airport charges of for example Texel, Midden-Zeeland, Hoogeveen, Hilversum, Budel, Teuge, Maastricht, Eelde, Rotterdam or Amsterdam. An approval procedure for Eindhoven and Twente airport was never implemented, since their status as military airports with civil co-use created a problem between the ministry of transport and the ministry of defence about the designated civil area of the airport.

21 The new regulation of Schiphol airport was developed in a working group consisting of members from the ministry of transport, the ministry of economic affairs, the NMa and the ministry of finance.

22 The slot allocation rules are now being reconsidered, to look for more market-oriented approaches.

23 Actually, the choice for RoR regulation of the aviation till was not the result of a more fundamental discussion about the well-known pros and cons of price cap regulation and RoR regulation. RoR regulation was introduced as a more or less inevitable component of the envisaged 'negotiated access' model.

24 An IPO of Amsterdam airport enables the selling shareholder, in this case the state, to cream at least a part of the capitalised future locational rents.

25 A state commissioner has always been a contradiction in terms. Each member of the supervisory board shall only serve the company's interest, independently, without any order or consultation. As long as the public interest and company interests point in the same direction, the potential conflict of interests remains hidden. At the same time, the impression is created that the state is able to influence a company's policy and to safeguard the public interest through its state commissioners. But this is an illusion.

26 The so-called Structuur NV.

27 This danger is rather small if one realises that the profitable commercial activities are more or less rooted in the aviation activities. Neglecting the aviation activities will inevitably have a strong negative impact on commercial activities.

28 The balance sheet will not be affected by these changes, since it only refers to the bare legal ownership. The airport operator keeps all possibilities to exploit the land as he intended to do.

29 Various financial compensation principles have been developed for different situations.

Ashford, N. and Moore, C.A. (1999) Airport Finance, Woodhouse Eaves.

Ashford, N. and Benchemam, M. (1987) "Passengers' choice of airport: an application of the multinomial logit model", Transportation Research Record, 1147,1-5.

Baumol, W.J., Panzar, J.C. And Willig, R.D. (1982) Contestable Markets and the Theory of Industry Structure, Harcourt Brace Jovanovitch.

Bier, C. (2001) "Network Access in the Deregulated European Electricity Market: Negotiated Third Party Access vs. Single Buyer", German Working Papers in Law and Economics, Vol. 2001, Article 17.

Carney, M. and Mew, K. (2003), "Airport governance reform: a strategic management perspective", Journal of Air Transport Management, 9, 221-232.

Civil Aviation Authority (2000), The "Single Till" and the "dual till" Approach to the Price Regulation of Airports, Consultation paper, London.

Doganis, R. (1992) The Airport Business, Routledge, London.

Engel, C. (2002) Verhandelter Netzzugang, (Negotiated Access), Gemeinschaftsgüter: Recht, Politik und Ökonomie, Preprints aus der Max-Planck-Projektgruppe, Recht der Gemeinschaftsgüter, 2002/4, Bonn,

Forsyth, P. (2003) Creating and Shifting Locational and Monopoly Rents at Airports, presentation at the Hamburg Aviation Conference 2003.

Frontier Economics (2000) Schiphol Airport: Market Definition Study, A report prepared for NMa, London.

Furuichi, M. and Koppelman, F.S. (1995) "An analysis of air travellers' departure airport and destination choice behaviour", Transportation Research A, 28A, No. 3, 187-195.

Graham, A. (2001), Managing Airports, an International Perspective, Butterworth/ Heinemann.

Greenhut, M.L., Norman, G. And Hung, C. (1987), The Economics of Imperfect Competition: A Spatial Approach, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Harvey, G. (1987), "Airport choice in a multiple airport region", Transportation Research A, 21, No. 6, 439-449.

Larouche, P. (2000) "Relevant market definition in network industries: air transport and telecommunication", Journal of Network Industries, 1, 407-445.

Ministry of Economic Affairs (1999) Publieke belangen en marktordening, Liberalisering en privatisering in netwerksectoren (Public interests and market structure, Liberalisation and privatisation in network industries), The Hague.

NMa (2001) Rapportage Luchthaventarieven Schiphol (Report airport charges Schiphol), The Hague.

Schiphol Group (2003) Annual Financial Report 2002.

Starkie, D. (2002) "Airport regulation and competition", Journal of Air Transport Management, 8, 63-72.

Starkie, D. and Yarrow, G. (2000) The Single Till Approach to the Price Regulation of Airports, CAA, London.

Veldhuis, J.G. and Pelger, M. (2003) "Airport competition and changing landside accessibility", paper to be presented at the ATRS Conference, Toulouse.

Wit, J.G. de (1996) "De kwetsbaarheid van meervoudige airportsystemen; lessen voor nieuwe luchthavenplanners, (The vulnerability of multiple airport systems; lessons for new airport planners)", Tijdschrift voor Vervoerwetenschap, No. 4, 355-370.