EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Without a powerful, industry-dominating strategy, you’ll spend the next several years generating very little traction in the marketplace. To address this challenge, we’ve integrated several of the best-known strategic concepts into one comprehensive framework — called The 7 Strata of Strategy — for scaling up your business. The 7 Strata defines the complete brand — and then everything aligns with this. And it provides an agenda for the strategic thinking team to create and maintain a competition-crushing, differentiated approach to a specific market. There are recommended resources to bolster your team’s understanding of each stratum. It’s hard work, which is why we suggest you assign this effort to a handful of leaders.

The recession decimated the building industry after the global financial crisis, but Vancouver, Canada-based BuildDirect.com, which sells building materials through its website, has doubled sales each year since Jeff Booth and Rob Banks founded it in 2003. Its 2014 run rate is $200 million, and it’s quickly heading toward a billion. Why? Strategy!

When you nail your strategy, top-line revenue growth and fat margins come almost effortlessly. For those experiencing this kind of rapid and sustainable growth, skip this chapter. (We’re serious!) Don’t risk messing up your winning strategy. Your only challenge, like that of BuildDirect.com, will be to heed the warning made famous by HP’s Dave Packard, who was once advised that “more companies die from indigestion than starvation.”

“More companies die from indigestion than starvation.”

For leaders of companies that are not buried by too much business, read on. Without an effective strategy, you’re going to spend the next several years executing a plan that is less than optimal and leaving a pile of money on the table. Worse, you’ll keep the doors open for savvier competitors to swoop in and take over your industry.

Using BuildDirect.com as a case study (along with ample other examples), we’ll walk you through the one-page 7 Strata of Strategy tool it used to dominate its industry. The 7 Strata is a comprehensive framework for creating a robust strategy that differentiates your company from the competition and helps you establish the kind of roadblocks that allow you to dominate your niche in the marketplace.

For those familiar with the One-Page Strategic Plan (OPSP), think about the 7 Strata framework as the “page behind the page” — a worksheet drilling down into the details of your Sandbox (WHAT you sell to WHOM and WHERE), Brand Promises, and the Profit per X and Big Hairy Audacious Goal (BHAG®), which are highlighted in columns 2 and 3 of the OPSP.

The idea is to use the 7 Strata worksheet to answer a series of strategic questions and plug some of the answers into the appropriate spaces on the OPSP. The questions will help you make key strategic decisions. Why aren’t there spaces for all the 7 Strata answers on the OPSP? Because some should be kept confidential, and others cover details behind a few specific decisions summarized on the OPSP.

With each of the 7 Strata (levels) of decision-making, we’ll share a KEY RESOURCE to help you dig deeper into that particular aspect of your strategy. In most cases, entire books have been written about the Strata, and where an appropriate one exists, we refer to it. We strongly suggest dividing up the workload and having each executive team member read one of the recommended books or articles and then brief the rest of the executives. Strategy is what a senior team should be spending the bulk of its time on, anyway — not fighting fires on a day-to-day basis, which is best left to the middle managers.

NOTE: If this work were easy, every company would have a killer strategy. The process can be very uncomfortable for CEOs, who might feel they should already have all the answers. After all, it’s the CEO’s primary job to set and drive the strategy of the business. At the same time, it’s a very messy and creative process requiring lots of learning and talk time with a myriad number of customers, advisors, and team members. This can be particularly difficult for engineering types who want to follow a sequential process to finding the right answers. It just doesn’t happen that way.

Of all the methods we teach, this is the one where you must truly “trust the process.” Persevere, keep searching (it took Wayne Huizenga, a very savvy serial entrepreneur, several years to find the key to making AutoNation’s strategy work), and the magic will occur.

As mentioned in “The Overview,” it’s helpful to think about strategic planning in terms of two separate and distinct activities (and teams): strategic thinking and execution planning. The 7 Strata framework is one of the key tools guiding the strategic thinking agenda of the company. The 4Ps of marketing (Product, Place, Price, and Promotion) is the other guiding framework. From our perspective, marketing strategy = strategy. For an update to the 4Ps, search the Internet for ad agency Ogilvy & Mather’s 4Es of marketing (Experience, Everyplace, Exchange, and Evangelism), and add these to your marketing meeting and strategic thinking agendas.

The first step in completing the 7 Strata and working through the 4Ps or 4Es of marketing is designating a strategic thinking team. Select no more than three to five people to meet for an hour or so each week to discuss each of the Strata and other issues of strategic importance. It’s not sufficient to schedule strategic thinking time once every quarter or year. It’s all about iterations: making a few decisions, testing them, and coming back to the table the following week for discussion. It’s these ongoing weekly meetings that will keep your strategy relevant and fresh.

“It’s not sufficient to schedule thinking time just once every quarter or year.”

Jim Collins refers to this team as “the council.” Grab a copy of Collins’ Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap... And Others Don’t and read the three most important pages ever written in business — Pages 114 to 116 — where he describes the 11 guidelines for structuring such a council. Included are recommendations on who should be on this council. Besides a few key members from the senior team, you might include someone with specific industry or domain knowledge underpinning your strategy.

The council doesn’t accomplish its work in isolation. The council members are expected to spend time each week talking with customers and employees and checking out competitors, extracting insights and ideas to fuel their strategic thinking. People get the sense that geniuses like Steve Jobs sat around humming in a lotus position, hoping divine intervention would strike. To the contrary, Jobs spent most afternoons engaged directly with customers, much to the chagrin of his team. And, underscoring the link between strategy and marketing, he chaired only one function — marketing — via a three-hour, Wednesday-afternoon meeting.

Jim Collins emphasizes that holding the council isn’t a consensus-building exercise. The team members are there to give advice to the CEO. And they are there to help the company illuminate the winding road ahead, which is why strategist Gary Hamel calls these groups “headlight teams.” The key is to help the CEO see beyond the speed at which the company is growing so he or she can keep the company from careening off the side of the road.

In the end, strategic decisions need to be made, and it’s the job of the CEO to make them. Yet it’s advisable to recruit several pairs of eyes (and to have frequent contact with the market) to help you navigate.

The creation of the 7 Strata of Strategy framework was inspired by a book written by Walter Kiechel III, a former Fortune editor and Harvard Business Publishing editorial director. Titled Lords of Strategy: The Secret Intellectual History of the New Corporate World, it chronicles the relatively short 50-year history of corporate strategy and the four men who were the pioneers in the field. For leaders interested in the topic of strategy, it’s an invaluable resource documenting, in one easy-to-read package, the frameworks used by Boston Consulting Group, Bain & Co., McKinsey & Co., Porter Consulting, and many others.

What struck us, as we read the book, is how overly complex many of the models are. They were designed for large global conglomerates. At the same time, stating a simple definition of one’s market (or Sandbox) and a few Brand Promises, as required on the OPSP, was too simplistic.

There needed to be something in the middle — for middle-market firms — that integrated several important aspects of strategy, and thus was born the 7 Strata of Strategy framework. We tested it with several firms for three years and found that it drove the exact kinds of strategies that helped companies like BuildDirect.com dominate their industries. We knew then that we had something powerful, yet simple enough to help gazelles scale.

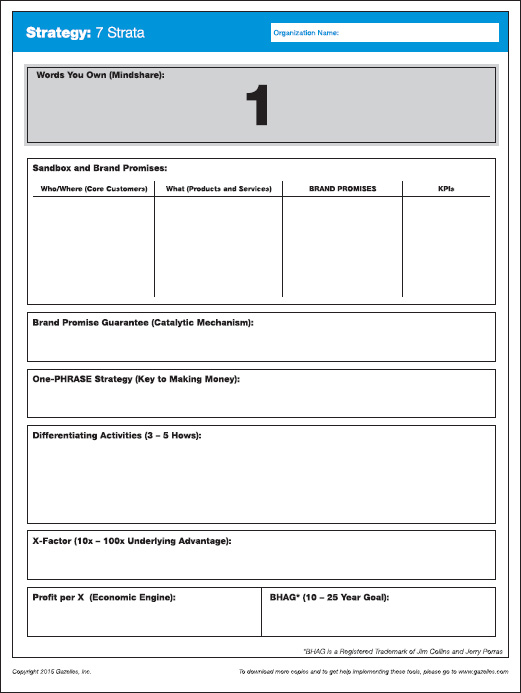

Again, for those interested in the relationship between the 7 Strata and the OPSP, think of the 7 Strata as the pure “strategic thinking” piece of the strategic planning that the OPSP guides. As we take you through each of the 7 Strata, we suggest that you download the one-page worksheet at scalingup.com and follow along. Here are the 7 Strata:

1. Words You Own (Mindshare)

2. Sandbox and Brand Promises

3. Brand Promise Guarantee (Catalytic Mechanism)

4. One-PHRASE Strategy (Key to Making Money)

5. Differentiating Activities (3 to 5 Hows)

6. X-Factor (10x – 100x Underlying Advantage)

7. Profit per X (Economic Engine) and BHAG® (10- to 25-year goal)

NOTE: Most strategy frameworks include some kind of competitive analysis. As you work through the 7 Strata, it’s illuminating for the team to discuss how the competition might fill in each level — and to do the same for firms you highly respect outside your industry. This will give you additional insight into the market, the competition, and ways to differentiate your strategy.

Words You Own (Mindshare)

Words You Own (Mindshare)

KEY RESOURCE: Search Engine (Google, Bing) tools

No one can own the word “automobile” in the minds of the marketplace, but Volvo owns “safety.” Meanwhile, BMW has molded every decision about the design and marketing of its cars around two words: “driving experience.” Though BMW is also considered a luxury and performance vehicle, the company’s obsession with the driving experience is what continues to differentiate the car from other mass luxury vehicles.

If you’re lucky, the name of your company becomes the word you own, like Facebook. Or your company name can clearly describe what you do and represent the words you want to own in the minds of your market, like “trench safety.” If you’re entrepreneurial, you can name a new niche and then own it by default. J. Darius Bikoff did this in the bottled water industry in 1996. No one could own “bottled water,” but he added some vitamins and minerals and created the first new beverage category in 25 years, called “enhanced waters.” Though consumers were unaware of this term, Bikoff’s Glacéau brands captured the attention of the big players in the industry. Coke snatched up the company for $4.1 billion just over a decade later.

The developers of Snapchat combined these ideas, creating a new category of chat and cleverly naming the venture after the two words the application now owns in the minds of the market. Launched in September 2011, the company now has a multibillion-dollar valuation.

It’s a fun and useful exercise to think of well-known brands (and your competition) and discern the words they own. In the end, that’s what branding is all about: owning a small piece of the mind-space within a company’s targeted market, whether that’s in a local neighborhood, an industry segment, or the world. If you want to hurt a competitor, steal its word, as Google did with Yahoo, becoming the “search” engine of choice.

Since 87% of ALL customers (business, consumer, and government) search the Internet to find options for purchasing products and services, you need to dominate these search engines. The key is owning words that matter — the ones people think about and use to search for your products and services.

“The key is owning words that matter.”

These search engines are useful tools for discerning your company’s or competitors’ success at owning a certain set of words. Take a moment to search the words or phrases you think you should own in the minds of your customers, and see how high your company ranks — or whether your lesser competitors are outranking you. Then go to the Google AdWords Keyword Planner to see how many times someone has searched for your target word or phrase. More important, this tool will show you what related words are searched and with what frequency, both locally and globally. This will help you refine the words you choose to dominate.

The tool will tell you how many advertisers are bidding for a particular term in the Google AdWords program. It also gives you a sense of the difficulty you will face if you want to own that search term, letting you know if the competition is low, medium, or high.

Your first instinct may be to go after the most popular terms, whether you are planning to use paid advertising or “organic” search engine optimization techniques. However, you may be better off picking slightly less used but still popular terms to point potential customers to specific products or services you offer.

Then take a page from the best-selling book The New Rules of Marketing & PR: How to Use Social Media, Online Video, Mobile Applications, Blogs, News Releases, and Viral Marketing to Reach Buyers Directly. As author David Meerman Scott says, “You are what you publish.” Hire writers and videographers to create case studies, white papers, and videos that naturally catch the attention of the search engines (and media) and educate the customers about the words you want to own. Videos and images have dominated over text ever since Google purchased YouTube.

BuildDirect has dived into this approach. While it is armed with a clever name that describes what it does, co-founder and CEO Booth knows that customers don’t think, “I’m looking to purchase building supplies direct.” BuildDirect has created algorithms that help customers find products in just a handful of the thousands of building product categories — the ones the company has decided it can dominate. It has optimized its website so that it will show up high in natural Web searches — meaning unpaid searches — for terms such as “laminate flooring” and “hardwood flooring.” If you go to the company’s website, you’ll see that it’s prominently displaying these terms on the home page, along with photos. Are you doing the same?

BuildDirect has built its search engine rankings for its chosen terms by publishing unbiased content — which includes these keywords — to help customers tackle their building projects. These articles, housed within the BuildDirect Learning Center, aren’t thinly disguised commercials for BuildDirect.com. They are useful, well-written articles that might otherwise appear in a home remodeling publication. One division is the Laminate Flooring Learning Center. This section is chockfull of useful information aimed at homeowners considering this flooring choice, such as a description of laminate flooring, with its pros and cons, an explanation of the manufacturing process, a listing of the types of laminate flooring, cleaning and care information, and a buying guide.

If you were stumped about whether to go with wood flooring or laminate, the information would be helpful — and that’s why it pulls in visitors to the site. “Our key customer is Debby the Do-It-Yourselfer,” explains Booth. “We try to arm her with as much information as we can to help her make an unbiased decision.” People don’t want to be sold; they want to be educated.

The site’s clientele extends beyond home improvement buffs. Many professionals in the building trades also purchase materials through the site, and the content is sophisticated enough to give them the information they need to serve their customers well, too.

By focusing the site on the customer and his or her needs — and not on tooting its own horn — BuildDirect.com has taken control of the words it wants to own in its marketplace. And, as a result of this smart strategy, much of its business comes in through customers’ unpaid Web searches for terms such as “laminate flooring,” says Booth. This is what is driving the company’s phenomenal revenue growth.

For more on how to use content to drive revenue, read Joe Pulizzi’s highly insightful Epic Content Marketing: How to Tell a Different Story, Break through the Clutter, and Win More Customers by Marketing Less.

If you focus on only one of the 7 Strata, this first one is the most important in driving revenue. The rest help you defend your niche, simplify execution, and turn your revenue into huge profit.

NOTE: Owning a word or two also applies to your personal brand (e.g., Tim Ferriss owns the term “4-Hour.”) Here’s a link to a piece Verne wrote as a LinkedIn Influencer titled “Your Career Success Hinges on One Word: Do You Know It?”: http://tiny.cc/success-one-word

Dominating the search engines isn’t the only test. Your identity as the maker of the safest car or the “king of enhanced waters” might be well-entrenched in the minds of the right people, and therefore it might not be necessary to pop high in searches. The key is picking a niche and owning (or creating) the words in the minds of the people you want as your core customers.

Sandbox and Brand Promises

Sandbox and Brand Promises

KEY RESOURCES: Robert H. Bloom and Dave Conti’s book The Inside Advantage: The Strategy That Unlocks the Hidden Growth in Your Business, and Rick Kash and David Calhoun’s book How Companies Win: Profiting From Demand-Driven Business Models No Matter What Business You’re In

There are four key decisions to make on stratum 2:

1. Who/Where are your (juicy red) core customers?

2. What are you really selling them?

3. What are your three Brand Promises?

4. What methods do you use to measure whether you’re keeping those promises? (We call these the Kept Promise Indicators, a play on the standard definition of KPIs.)

Who/Where: Bloom and Conti, authors of The Inside Advantage, implore companies to get crystal clear about Who and Where their juicy red core customer is — the customer from whom the business can mine the most profit over time. Their warning is to define customers beyond a pure demographic. For Nestlé’s Juicy Juice, pigeonholed early on as just another sugary drink for children, Bloom’s team redefined the Who as “a mom who wants her young children to get more nutrition.” For a particular nurse-staffing firm, the core customer is actually members of its team — the travelling nurses it places with hospitals — due to a global shortage of nurses. Bloom and Conti’s book will help you discern a concrete definition of your core customer.

Kash and Calhoun, authors of How Companies Win, further suggest that there is a niche within any industry that represents no more than 10% of the total customers but holds a disproportionate percentage of the profit — what are termed profit pools. For instance, in the dog food industry, Kash’s team segmented the market based on the relationship between an owner and her dog (vs. the size of the dog) and found a group of owners they labeled “performance fuelers.” These are owners who are active — biking, hiking, jogging, and running — and want their dog with them. Though they represent only 7% of all dog owners, they account for more than 25% of the profitability in dog food purchases. The key is finding that same niche in your industry and owning it through a highly focused product or service offering.

Once you know more specifically Who they are, it’s much easier to know Where to find them. The performance fuelers can be reached locally on a few key trails and via a couple of popular news sites and blogs.

For BuildDirect.com, as mentioned above, the core customer is “Debby the Do-It-Yourselfer,” not simply women ages 35 to 55. She represents a very specific persona and is highly predictable in where she can be reached — reading certain publications, shopping certain sites, and searching for specific products.

What: Bloom and Conti suggest that the primary mistake companies make in describing What they sell is to focus on the benefits and features. All sales are emotional, initiated through the heart (“No one was ever fired for buying IBM”) and then justified logically by the head. That’s why established brands play on people’s fear of purchasing from a new entry in the marketplace.

Summit Business Media (now Summit Professional Networks), an example that Bloom and Conti use in their book, offers “the indispensable source of authoritative information, data and analysis for the well-informed financial professional.” The concepts that the company is irreplaceable and helps its clients stay well-informed play to the financial professional’s emotional needs as much as business needs. Kash and Calhoun add that the What must encompass a 100% solution. Many business leaders are easily distracted by shiny objects; they move on too quickly to another product line, distribution channel, or niche before thoroughly locking down an existing one with an offering that completely does the job a customer needs to accomplish.

Winterhalter Gastronom GmbH, a German manufacturer of commercial dishwashing equipment, dominates the market in selling to large restaurant and hotel chains. These companies operate in a 24/7 environment and need dishes that not only are clean but look clean. Winterhalter engineered a complete solution for this niche, which included supplying water conditioners, specialty detergents, and a global quick-turnaround repair service to customers.

Brand Promises: Debby the Do-It-Yourselfer wants laminate flooring, and BuildDirect grabs her attention. So why should she buy from BuildDirect vs. its competitors? There have to be some compelling reasons that are evident from the moment she visits BuildDirect’s website. We call these reasons the Brand Promises. Most companies have three main Brand Promises, with one promise that leads the list.

For BuildDirect, the Brand Promises are “Best price, best customer service, and product expertise.” “Best price” is the lead promise. The key is to define the company’s Brand Promises quantitatively so they can be measured and monitored. Best price, in BuildDirect’s case, means 40% to 50% less than anyplace else where you can purchase a similar product. BuildDirect has teams monitoring prices daily to make sure that it can keep this promise, or that it exits certain products and categories when it can’t.

WARNING: Refrain from using the words “quality,” “value,” or “service” as Brand Promises. They are too vague. Their definitions may vary, depending on the group of customers you’re facing. McDonald’s delivers what Verne considers high value and service if it’s noon on Saturday and he and his wife are looking for a place where they can grab a quick bite with their four children without standing in a long line, and get a few minutes of peace while their two youngest play in the indoor playground. However, as a place to go on a date night, McDonald’s has little value to them. McDonald’s has defined its three measurable brand (value) promises as speed, consistency, and fun for kids. Getting clear about this and then delivering on these promises (including sending specific updates on these KPIs to its franchise owners daily) helped it pull off one of the most respected modern business turnarounds.

The right Brand Promise isn’t always obvious. Naomi Simson — founder of one of the fastest-growing companies in Australia, RedBalloon — was sure she knew what to promise customers who want to give experiences such as hot air balloon rides as gifts, rather than flowers and chocolates. Her promises included an easy-to-use website for choosing one of over 2,000 experiences; recognizable packaging and branding (think Tiffany blue, only in red); and onsite support.

It wasn’t until a friend and client mentioned that she was using the website as a source of ideas — but buying the experiences directly from the vendors — that Simson had an “Aha!” moment. She realized that other customers might be doing the same thing, assuming that RedBalloon must be marking up the price of the experiences to cover the costs of the website, packaging, and onsite support. To grow the business, she promised customers they would pay no more for the experiences they bought through RedBalloon than for those purchased directly from the suppliers; otherwise, customers would get 100% of their fee refunded. The company calls this promise, which is technically a pricing guarantee, a “100% Pleasure Guarantee,” to fit its brand.

KPIs (Kept Promise Indicators): A promise has no weight if you don’t keep it, resulting in lost customers and negative word-of-mouth publicity. Thus, it’s critical that you know how to measure daily whether you’re keeping your promises. At RedBalloon, Simson created a team that monitors pricing of its roughly 2,000 experiences to make sure that her customers can’t buy the experiences more cheaply from other vendors. This isn’t easy. The prices that suppliers charge for experiences like jet boating are subject to constant change because of factors such as fuel price fluctuations and insurance costs.

Rackspace, offering cloud-based hosting, is another company that has mastered Brand Promise KPIs. The company, based in San Antonio, has built its brand around the promise of “fanatical support.” This phrase appears smack in the middle of its website: “Fanatical Support: Over 1,400 trained cloud specialists, ready to help.”

The company measures its success in meeting this Brand Promise in three ways. The #1 measurement is uptime of a client’s site. Rackspace offers a money-back guarantee if there’s any downtime. If there is a problem, and a customer has to call in, that call will be answered in three rings. Rackspace installs red lights in its call centers that start to spin if a call is getting ready to go to a fourth ring. So that a customer doesn’t get transferred, that call will be answered by a level two tech. That’s what the customers want. Rackspace measures its performance on these three things, obsessively, every moment: uptime, calls answered in three rings or fewer, and lack of call transfers. The data is streaming all over its facilities. That’s how Rackspace grew from nothing to a market cap of more than $6 billion in a dozen years.

The BuildDirect team, similarly, has various Kept Promise Indicators it monitors to make sure everyone is keeping the company’s Brand Promise. Besides keeping an eye on competitors’ pricing, the company has set countless measures for how long someone is on a certain landing page; how long it takes for a customer service rep to respond to a question; and how simple it is for customers to find what they need and purchase it.

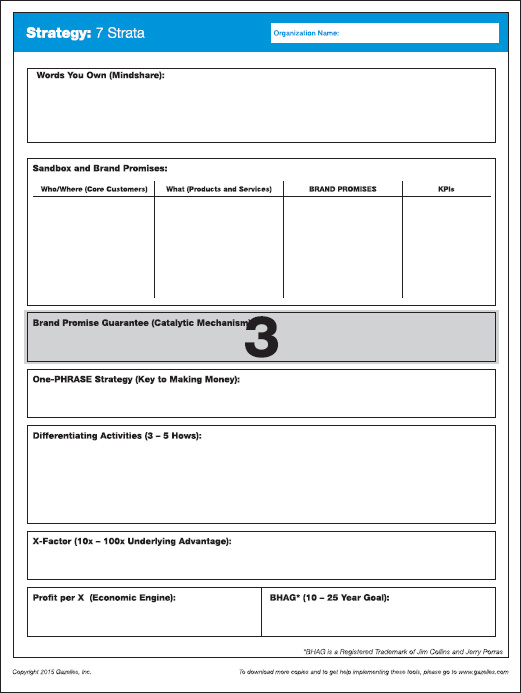

Brand Promise Guarantee (Catalytic Mechanism)

Brand Promise Guarantee (Catalytic Mechanism)

KEY RESOURCE: Jim Collins’ Harvard Business Review article “Turning Goals Into Results: The Power of Catalytic Mechanisms”

It needs to hurt to break a promise; otherwise, it’s too easy to let the moment pass. This is why Collins labeled what we call a Brand Promise Guarantee “a catalytic mechanism.” By promising to refund 100% of a RedBalloon gift voucher’s cost if the customer can find the experience for a cheaper price, the company’s guarantee puts heat on Simson’s team to keep their pricing promise.

The Brand Promise Guarantee also reduces customers’ fear of buying from you. In its early days, Oracle promised that enterprise software would run twice as fast on its database software as on competitors’ (in full-page ads on the back of Fortune magazine), or it would pay customers $1 million. Today, it offers a similar guarantee on its Exadata servers, except the reward is $10 million.

Professional service firms might offer “short pay” guarantees, giving the client an option to pay whatever he thinks reasonable if there are issues. Though 99% of clients won’t send less, the existence of the guarantee gives them the confidence to do business with the service firm and encourages customers to share their concerns.

In BuildDirect’s case, the company offers a 30-day, no-questions-asked money-back guarantee — and it will even pay the return shipping. This catalytic mechanism assures Booth that his team is focused on helping a customer choose the right building products.

Jim Collins’ article will give you many more examples, as will the marketplace, when you start paying attention to what other companies are doing to guarantee their promises.

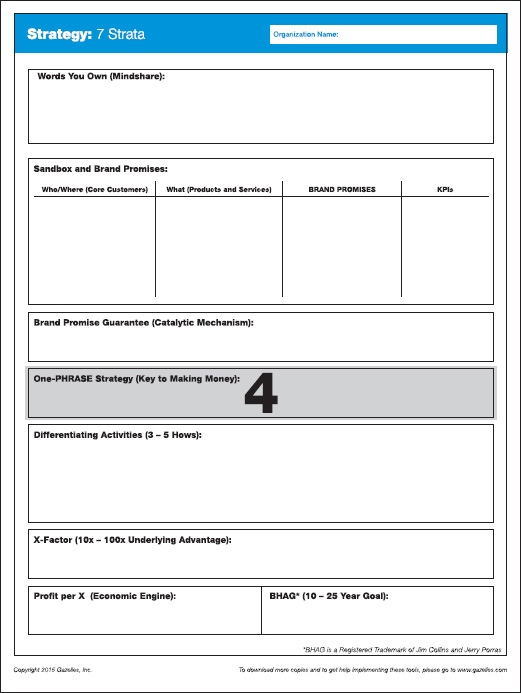

One-PHRASE Strategy (Key to Making Money)

One-PHRASE Strategy (Key to Making Money)

KEY RESOURCE: Frances Frei and Anne Morriss’ book Uncommon Service: How to Win by Putting Customers at the Core of Your Business

Do you dare to be bad? Even risk alienating or upsetting a large segment of potential customers? This is precisely what highly profitable and successful companies do, according to Frances Frei, a leading strategy professor at Harvard Business School, and Anne Morriss.

The first three Strata — owning mindshare, making and keeping promises, and backing them up with a guarantee — are expensive to accomplish. Making matters worse, in trying to address ever-increasing customer demands, the marketplace ends up “want, want, wanting” your margins away as the competition ramps up the “feature set and added services” war.

This is why it’s critical to identify your One-PHRASE Strategy. This phrase represents the key lever in your business model that drives profitability and helps you choose which customer desires to meet and which ones to ignore.

Take IKEA’s business model, based on “flat pack furniture.” Since IKEA doesn’t have to ship or warehouse air, its costs are considerably lower than competitors’, giving it a huge price advantage (its #1 Brand Promise). Add to this a flair for design and the best Swedish meatballs on the planet, and you have three Brand Promises that outweigh all the things people hate about IKEA — and it’s a long list!

Yet it’s specific trade-offs that power IKEA’s success and serve as a blocking strategy to competitors. Others simply don’t have the stomach to make people drive out of their way to visit a warehouse designed like a labyrinth, committing customers to a lengthy shopping experience. Pile on the need for assembly after the purchase, and it’s crazy to think anyone would shop at IKEA. And a lot of people don’t. But with just 6.8% global market share, IKEA is the world’s largest and most profitable furniture chain.

Apple’s One-PHRASE Strategy has been its “closed architecture,” the source of its phenomenal profitability. It also serves as a powerful blocking strategy, since Google and Microsoft are beyond the point of no return and would never be able to close their open systems. Again, most of the consumers in the world don’t find the trade-offs worth it, but that hasn’t kept Apple from being the most valuable company in the world.

Frei and Morriss’ overarching point is that great brands don’t try to please everyone. They focus on being the absolute best at meeting the needs/wants of a small but fanatical group of customers, and then dare to be the absolute worst at everything else. In turn, competitors, in striving to be the best in everything for everyone, actually achieve greatness in nothing — and end up as just average players in the industry.

We would share BuildDirect’s One-PHRASE Strategy, but we strongly suggest that the company keep it a strategic secret. Again, you don’t want to run around bragging about the key driver of your business’s profitability, at least in the early years.

The book Uncommon Service will give you a myriad number of examples and walk you through how to both “be bad” the right and highly profitable way and “be great” via a few Brand Promises. It takes real guts to ignore or even alienate 93% of customers, focusing instead on the 7% of the market that is fanatical about you and willing to put up with the trade-offs.

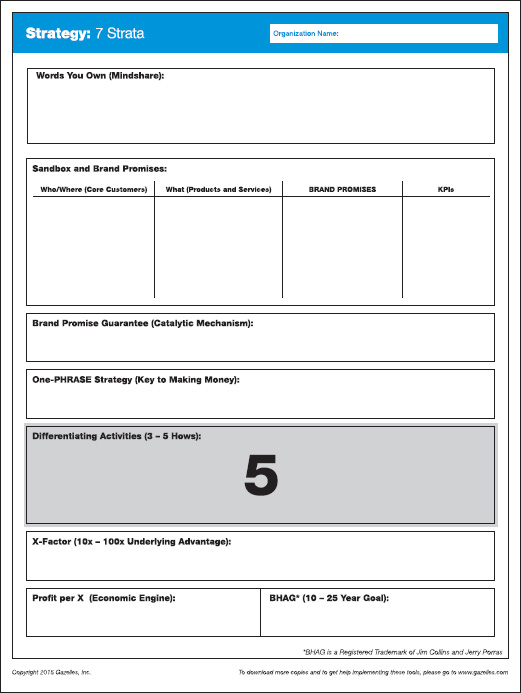

Differentiating Activities (3 to 5 Hows)

Differentiating Activities (3 to 5 Hows)

KEY RESOURCE: Michael E. Porter’s classic 1996 Harvard Business Review article titled “What Is Strategy?”

Underpinning the One-PHRASE Strategy is a set of specific actions that represent HOW you execute your business differently from the competition. According to well-known strategist Michael Porter at Harvard Business School, it’s at the “activity” level of the business where true differentiation occurs and the business model is revealed.

NOTE: This is the first time the term “differentiation” has been used. Competitors can pursue owning the same words, make the same Brand Promises, and offer the same guarantees. However, it’s HOW you deliver on your promises where differentiation occurs. Adds Kevin Daum, author of ROAR! Get Heard in the Sales and Marketing Jungle: A Business Fable, “a true differentiator can only be defined as something your competitor won’t do or can’t do without great effort or expense. Often these can take years to develop since if it can be done cheaply, easily and quickly it provides little or no competitive advantage.”

Again, Porter’s point is that this happens at the activity level of the business, as illustrated by the Southwest Airlines case he highlights in his HBR article referenced above. Southwest has a handful of hard-to-copy activities that differentiate it from competitors. In addition to not having advance-reservation seating, the airline flies just one type of aircraft (reducing the number of repair parts needed and giving it more flexibility to swap pilots), utilizes second-tier airports to reduce landing fees, favors point-to-point flights vs. the more expensive hub-and-spoke system, and nurtures a quirky culture that helps customers put up with all the negatives.

These activities serve as blocking factors precisely because all the other airlines, except copycat Ryan Air, are already invested in multiple aircraft, provide advance-reservation seating (it’s hard to take away something away you’ve already given the customer), are locked into expensive hubs, and have built cultures of unhappy employees!

The key is to choose HOW you go about delivering your products and services in your industry in ways that are nearly impossible for your competition to copy. Notice that these activities derive from Southwest’s One-PHRASE Strategy — “Wheels Up” (its expensive hunks of metal make money only when they are in the air) — helping the airline achieve this key result that drives profitability. Each layer of the 7 Strata of Strategy builds upon and reinforces the others.

In BuildDirect’s case, the reason it can offer such outstanding pricing, service, and guarantees is that there are a handful of unique ways in which it has structured the business model that afford it the ability to deliver on its Brand Promises. Specifically, BuildDirect:

1. Requires a minimum order of a pallet of material

2. Carries no name-brand products and instead provides a distribution channel for a number of small manufacturers with outstanding products

3. Requires cash in advance, even on its largest orders, which can be in the six figures

A particular competitor might share one of these approaches with BuildDirect, but it’s the unique combination of all three that underpins its differentiation. And it’s the distasteful nature of some of these activities — derived from its secretive One-PHRASE Strategy — that blocks the competition from copying them.

Read Porter’s article, along with Uncommon Service, and establish a set of activities — “how” you run the business — that is different from the norms of the industry, helps you drive profitability, and blocks the competition. This is a lot for a handful of activities to accomplish, but this is the source of your differentiation. Do the work!

As Porter summarizes, “A company can outperform rivals only if it can establish a difference that it can preserve.”

X-Factor (10x-100x Underlying Advantage)

X-Factor (10x-100x Underlying Advantage)

KEY RESOURCE: Verne’s Fortune article titled “The X-Factor”: http://tiny.cc/the-X-Factor

Why would BuildDirect allow us to share the details of its strategy? It’s because of a hidden X-Factor — a 10x-100x underlying competitive advantage over its rivals. Normally invisible to customers, this edge underpins the strategic activities described above and blocks competitors from even trying to copy BuildDirect. And it typically addresses a huge, established choke point in an industry.

Once you have such an advantage, it will usually let you decimate the competition, allowing you to sustain the kind of rapid growth that BuildDirect has sustained for more than a decade.

As Verne has discussed in Fortune, Chris Sullivan made the Outback Steakhouse restaurant chain successful by focusing on an early X-Factor. After working extensively in the restaurant industry, he knew the primary challenge for large restaurant chains is maintaining consistency in food quality and service. But why? As he continued to peel back the layers, he concluded that it was due to the industry’s average six-month turnover of general managers in stores, a statistic considered to be “just the way it is in the restaurant business.” Good managers were typically moved around to take over for bad managers, and great managers would eventually leave and start their own restaurants.

Recognizing manager turnover as the choke point in the industry, Sullivan and his team asked themselves a key question: What if we could keep a restaurant manager in the same restaurant for five to 10 years? This would represent a 10x to 20x improvement over the existing situation in the industry.

The key for Sullivan turned out to be an unusual compensation plan (think “differentiated activity”). Young people interested in becoming managers were asked to “invest” $25,000 in an Outback restaurant. Imagine one of your children coming home and sharing that they found a job managing a restaurant. After expressing your initial skepticism (“What, managing a steakhouse after obtaining a four-year degree?”), you get around to the all-important question: “So what does it pay?” Whereupon she explains that she actually needs to pay the company to get the job!

Here was the deal Sullivan pioneered: New managers would invest $25,000 and commit to staying for five years. Outback would take the first three years to train them to run a restaurant, paying a competitive wage. During the last two years, the new managers would get to run a restaurant on their own. If they hit certain performance milestones by the fifth year, they would get a $100,000 bonus — a 4x return on their investment — which would vest over the next four years. If they signed on to stay at the same restaurant another five years, they would receive the $100,000 in one lump sum, plus $500,000 worth of stock that would vest over the next five years.

The company ended up turning a bunch of people in their 20s into millionaires; 90% of managers stayed in the same restaurant for five years; and 80% stayed for 10 years or more. Most important, Outback’s theory was correct. The longevity of management led to consistency in products and service, helping Outback become the third-largest restaurant chain in the US, and the most profitable, before Sullivan stepped aside as CEO. (He’s now back turning around the company as this book goes to print.)

So how do you figure out an X-Factor? Start by asking: What is the one thing I hate most about my industry? What is driving me nuts? What is the choke point constraining the company? It could be a massive cost factor. It could be a massive time factor. The challenge is that you’re often too close to the situation and as blind as everyone else to the real problems that have been accepted as industry norms.

One clue to the source of the X-Factor is going back to your last 10 trade association meetings and gathering the titles of the various breakout sessions. Put them in an Excel spreadsheet, and see if there are any patterns of challenges facing your industry over the past decade. By focusing on these roadblocks, and figuring out a 10x to 100x advantage, you’ll have a huge leg up on the competition.

And you don’t have to run a business the size of Outback to put this principal into practice. Barrett Ersek, founder of lawn care company Happy Lawn, reduced the typical sales process from three weeks to three minutes. Using the latest digital technology and tax map data to estimate lawn measurements and offer instant quotes while customers were on the phone, he eliminated the need to have salespeople visit prospects’ homes and take manual measurements, write up quotes, and then schedule appointments. It’s not surprising that industry giant ServiceMaster bought Ersek’s $10 million company. At Holganix, Ersek’s new company — which manufactures and distributes organic fertilizer — he’s identified another X-Factor. But, like his One-PHRASE Strategy, he’s keeping it a secret.

BuildDirect’s X-Factor also remains a secret, as it should. But you can go to Verne’s Fortune article for additional examples. Then start brainstorming with your strategic thinking team about some possible 10x advantages.

Profit per X (Economic Engine) and BHAG® (10- to 25-Year Goal)

Profit per X (Economic Engine) and BHAG® (10- to 25-Year Goal)

KEY RESOURCE: Jim Collins’ Hedgehog Concept in Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap... And Others Don’t

The final two decisions cap the strategy with a single overarching KPI that Jim Collins labels “Profit per X” and a measurable 10- to 25-year goal referred to as a BHAG®, a term that Collins and Jerry I. Porras introduced in their book Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies. Both decisions round out Collins’ strategic framework that he calls the Hedgehog Concept in Good to Great.

The Profit per X metric represents the underlying economic engine of the business and provides the leaders with a single KPI they can track maniacally to monitor the progress of the business (a great luxury to have). Though the numerator can be any metric you like — profit, revenue, gross margin, pilots, routes, etc. — the denominator is fixed and represents your company’s unique approach to scaling the business. And it generally ties back to the One-PHRASE Strategy (all of this stuff links together). While most airlines focus on profit per mile or profit per seat, Southwest focuses on maximizing profit per plane, which aligns with its One-PHRASE Strategy of “Wheels Up.”

As we saw in Alan Rudy’s story in Chapter 2, he took a similar approach in the business of answering phones. While everyone else focused on revenue per minute and profit per minute, he looked at the industry through a different lens and drove the business to maximize profit per booked appointment. The result: revenue reached an industry high of $5 per minute, vs. an average of $1.25 per minute. At Gazelles, we used to obsess over profit per event; now it’s profit per long-term client.

As leaders set the ultimate long-term, 10- to 25-year goal for their companies, we see a lot of sloppy work — a random number or statement of aspiration with no real connection to a company’s underlying strategy.

Microsoft’s BHAG®

“When Paul Allen and I started Microsoft over 30 years ago, we had big dreams about software. We had dreams about the impact it could have. We talked about a computer on every desk and in every home. It’s been amazing to see so much of that dream become a reality and touch so many lives. I never imagined what an incredible and important company would spring from those original ideas.”

— Bill Gates at a news conference announcing plans for full-time philanthropy work and part-time Microsoft work, June 15, 2006, Redmond, Washington

Collins placed the BHAG® in the center of his Hedgehog Concept, noting that it must fully align with all the components of your strategy. It’s why we’ve made it the seventh and final stratum. And we’ve discovered that the best unit of measure for the BHAG® is the X from the Profit per X.

NOTE: Your BHAG® should be measured in the same units as the X. This is a key point. Since Southwest Airlines is focused on profit per plane, it made sense that the company set a long-term goal to have X number of planes in the air. The Profit per X and the BHAG® need to align very tightly.

The BHAG® must also align with the Purpose of the company, as we explain in the chapter on the One-Page Strategic Plan. RedBalloon set an aggressive BHAG® to sell 2 million experiences in 10 years, a goal established in 2005, when it sold only 7,500. Simson, founder and CEO, reasoned that to truly change gifting in Australia forever (tapping people’s desire for experiences vs. stuff), RedBalloon needed to touch the lives of 10% of Australians. At the time, there were 20 million Australians, so reaching 2 million experiences sold was the goal. It then made sense for RedBalloon’s primary KPI to be profit per experience.

BuildDirect’s business model is very different. It operates in the retail building-supply industry, where competitors focus on metrics like profit per square foot of retail space, profit per SKU, and same-store sales growth. Booth has built the company based on maximizing profit per “building product category.” To reach Fortune 500 status by 2023, Booth has set a BHAG® to dominate just 20 of the more than 1,000 specific product categories (2% of all building categories — that’s hyperspecialization). Figuring that each category represents $500 million to $2 billion in revenue, BuildDirect should reach $10 billion to $20 billion in revenue in just 20 short years since its launch, if it is not purchased in the meantime.

BuildDirect’s strategy can be stated simply, but there is nothing simple about it. If you’re a “Debby the Do-It-Yourselfer” in North America (it’s expanding internationally) and want laminate flooring, you’ll find it easily via the search engines. Debby will likely find the promise of 40% to 50% savings an appealing value proposition, in light of the access she will get to the company’s expertise and the ease of purchasing from the comfort of her home or office, with products delivered directly to the construction site.

And Debby has no fear of being sold something she doesn’t want. If, for any reason, she doesn’t want what was shipped, she has 30 days to send it back, and BuildDirect will pay the return shipping. How can Booth afford to offer this? BuildDirect has a secret One-PHRASE Strategy that makes it a lot of money. And though elements of its model are unpleasant for customers, the Brand Promises outweigh how the company goes about its business (e.g., if Debby wants this laminate flooring, she’ll need to order at least a pallet of material; be willing to forgo the big brand names; and pay fully in advance).

BuildDirect doesn’t mind that we share its strategy because its top-secret X-Factor, which took years to perfect, provides a 10x advantage over any competitor that might try to copy the rest of its strategy. That’s why Booth figures that the company needs to dominate just 20 of more than 1,000 categories to reach Fortune 500 status. And to monitor its progress, BuildDirect focuses on maximizing its profit per building category, helping its leaders know when they’ve maxed out a category and need to exit it or add a new one.

The payoff is huge if you figure out all of the attributes of the 7 Strata. As with all of our tools, nail down what you can and keep moving. Set up your strategic thinking team, have each member read (and master) one of the referenced books or articles, and start testing your theories and honing your strategy to perfection. You’ll know you’re on the right track when sustained revenue growth and great margins start coming more easily.

It’s very difficult work, and your strategic thinking team may feel both lost and outright dumbfounded in the beginning, but trust the process. Keep meeting each week and talking through the ideas, and answers will come to you. If you need help, Gazelles has some top-notch strategy consultants, with experience helping many companies work through these Strata, who can help you do some of the heavy lifting.

In the last chapter of the “Strategy” section, we’ll take several decisions from the 7 Strata and integrate them into the OPSP: the one-page vision around which to align the entire company.