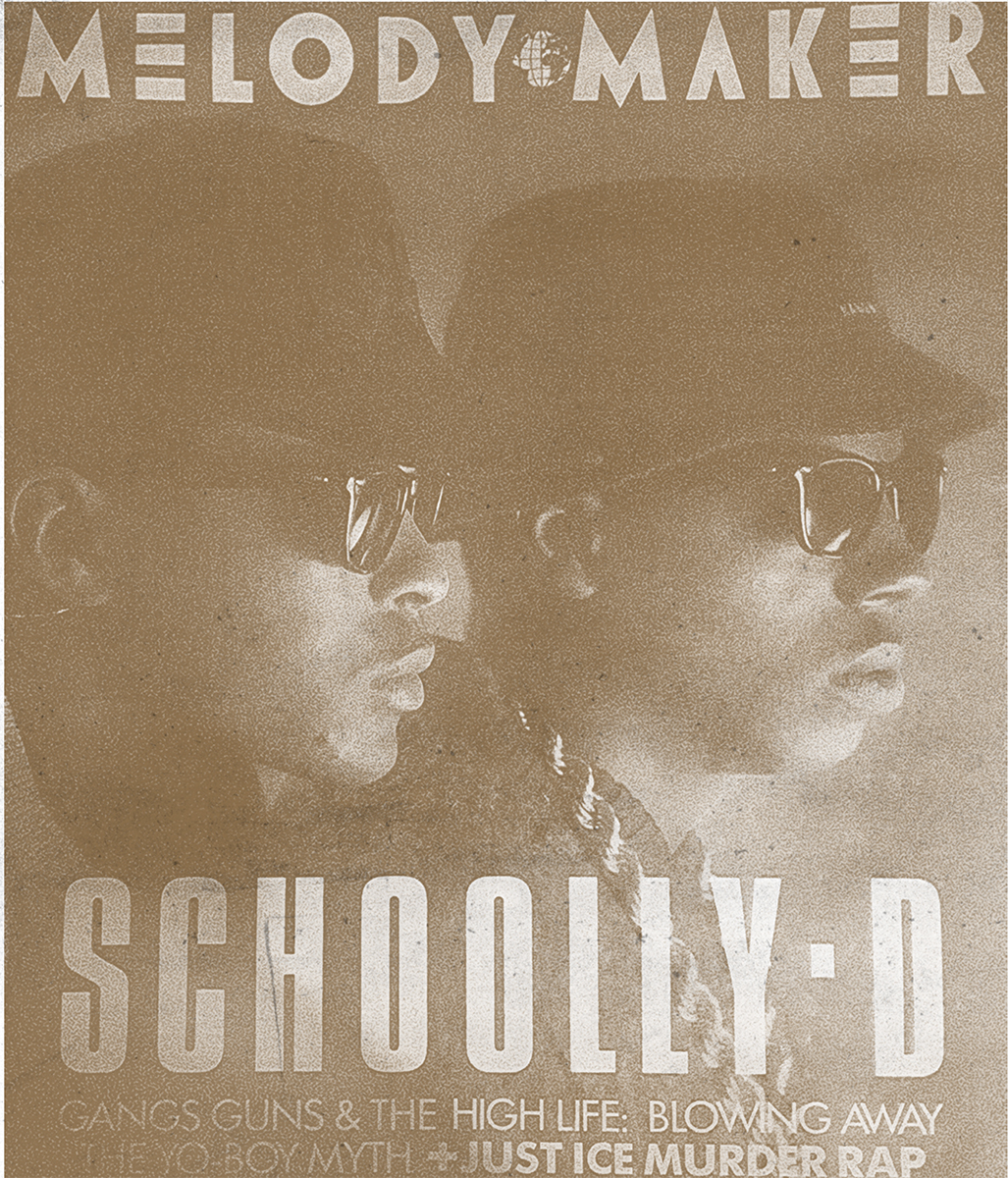

Schoolly D (right) and his DJ Code Money appeared on the cover of the November 15, 1986, edition of British publication Melody Maker.

IN 1982, RAP GOT A GLIMPSE OF ITS FUTURE.

President Reagan gutted school programs and Martin Luther King Jr. did not yet have a holiday. The Los Angeles Lakers defeated the Philadelphia 76ers to win the NBA finals, and the Crips and Bloods gangs ruled South Central. The first CD player was sold; disco was dying and gangster rap was about to be born. Snoop Dogg was eleven years old and Ice Cube was thirteen, and they lived in Long Beach and South Central, respectively. A seventeen-year-old Dr. Dre got his first set of turntables after listening to Grandmaster Flash’s “The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel.” A twenty-four-year-old Ice-T was transitioning from a life of crime to being a rapper at Radio Club, aka Radiotron, the only rap club in L.A.

At this point, rap records were mostly party songs brimming with braggadocio and good-natured rhymes. In 1979, rap took its first major commercial step forward with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” the genre’s first mainstream hit. The song’s music was blatantly appropriated from Chic’s disco record “Good Times” and its rhymes, in part, were lifted from Grandmaster Caz. Rappers Wonder Mike, Master Gee, and Big Bank Hank delivered simple, playful lyrics about their affinity for fashion, the desire to get with women, and the awkwardness of eating substandard food at a friend’s house. Even at a time when rapping was in and of itself revolutionary, the Sugarhill Gang’s lyrics, and those of such contemporaries as Kurtis Blow and the Funky 4 + 1, were little more than conversational, simplistic, and occasionally witty barbs that rhymed. Since the overall genre was in the infancy of its artistic evolution, most rappers of this era were still developing their styles and songwriting skills. Still, their delivery, concepts, and rhyme patterns, which were relatively straightforward, were nonetheless groundbreaking.

TIMELINE OF RAP

1985

Key Rap Releases

1. LL Cool J’s Radio album

2. Doug E. Fresh & The Get Fresh Crew’s “The Show” b/w Doug E. Fresh & M.C. Ricky D’s “La Di Da Di” singles

3. Schoolly D’s “P.S.K. What Does It Mean” and “Gucci Time” single

US President

Ronald Reagan

Something Else

The first Internet domain name, symbolics.com, was registered.

When 1982 came along, pioneering Bronx hip-hop DJ Grandmaster Flash and his rap crew, the Furious Five, came with it. With “The Message,” the group’s revolutionary recording, rapper Melle Mel described the desolate neighborhoods that many members of the rap community called home. “Broken glass everywhere,” Melle Mel rapped at the start of the first verse. “People pissin’ on the stairs, you know they just don’t care.”

“The Message” was a dark, somber song that spoke profoundly of the reality that many black people in America were experiencing and which stood in stark contrast to the festive music most rappers were releasing at the time.

For many rap fans, it was the first time they’d heard any sort of profanity on a record. A young Jayo Felony, a future gangster rapper who would be signed to Def Jam Recordings, was floored when, at the chaotic end of “The Message,” Melle Mel and his crew are seemingly apprehended by police and an officer (or someone impersonating an officer) blurts out, “Get in the goddamn car.” Those lyrics are remarkably tame compared to those uttered by rappers today, but in 1982, they were shocking.

The lyrics resonated with Jayo Felony and the rap-buying audience in a new, piercing way because they signaled a key change in rap. For the first time, the rage, chaos, and feelings of helplessness of blacks in America had been presented in a rap song. Moreover, Melle Mel presented himself as someone caught in systematic degradation and oppression. Although political messaging had been present in other rap songs, by Kurtis Blow for instance, it had never been presented in such a stark, serious, and striking manner.

Then, in 1984, gangster rap forefather Schoolly D flipped the script. Inspired by “The Message,” the pioneering Philadelphia rapper made a record called “Gangster Boogie,” in which he played the role of someone who menacingly instilled fear in and perpetuated crimes against the people living in the abhorrent conditions of the ghetto that Melle Mel had described. Schoolly D pressed it up on vinyl and took it to radio DJ Lady B, whose “Street Beat” show on Power 99 in Philadelphia was one of the most influential rap radio shows in the country at the time.

Lady B gave it to Schoolly D straight: No record company was going to sign him or distribute his records. The reason? He was rapping about weed and guns. Schoolly D, though, did not think his music was abrasive.

“I was being an artist,” Schoolly D said. “I grew up listening to [comedic legend] Richard Pryor on the radio on Saturday night. Late Saturday nights, the DJ would put on [his album] That Nigger’s Crazy. We didn’t think nothing of it. It was art. To us, it was art. To you [outsiders], it was just like, ‘We’ve got to stop these voices.’ Motherfuckers were listening. Then when they started listening, it was like they didn’t understand. I tell people now, ‘I don’t give a fuck what y’all thought. You have to understand that. I was making records for my peers, to uplift my situation, and it was workin’. I wanted to tell my stories the way I wanted to tell my stories. That’s why I never wanted to change my art.”

Faced with the sobering reality that he might never get radio play or a record deal, Schoolly D started saving up to press his own records. He connected with the buyers at influential mom-and-pop Philly record shops such as Funk-O-Mart and Sound of Market. Philadelphia was a bit player in rap at the time, but the city was on the cusp of an explosion thanks to Pop Art Records, which released early singles from burgeoning rap artists Roxanne Shanté, Steady B, and MC Craig G. For the mom-and-pop shops, independently released rap records were particularly attractive because corporate record stores typically didn’t carry much rap. Schoolly D was encouraged by the feedback he got from Philly’s independent record retailers.

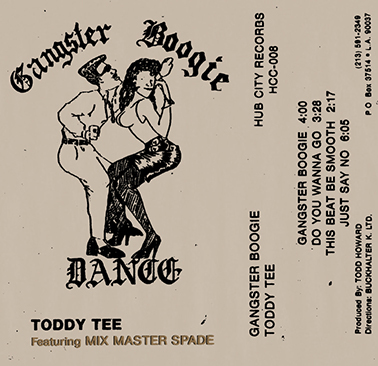

MIX MASTER SPADE

This pioneering rapper-singer-mixtape maestro helped popularize early Compton rappers. As Los Angeles–area rap evolved in the mideighties from the electro sounds of Egyptian Lover, World Class Wreckin’ Cru, and others, Mix Master Spade made mixtapes and singles with a singsong style that featured collaborations with such protégés as Toddy Tee (“Just Say No”) and King Tee (“Ya Better Bring a Gun”). The Compton Posse leader helped his city develop a buzz on the local market prior to N.W.A putting it on the global map a few years later.

The works of generations of rappers were inspired by the pulp street novels of such revered writers as Iceberg Slim and Donald Goines. Their gritty stories featured graphic tales of pimping, prostitution, and murder, and the narratives were often inspired by the authors’ real-life experiences. Ice-T took his name in order to pay homage to Iceberg Slim, while Goines’s Crime Partners was adapted into a 2001 film that featured Ice-T and Snoop Dogg. Goines’s Never Die Alone was made into a 2004 film starring DMX.

AUTHOR |

FIRST PUBLISHED |

SEMINAL BOOK |

Iceberg Slim |

1967 |

Pimp |

“All the record stores said that if I pressed the record up, they’d sell them,” Schoolly D said. “So I did it.”

Launched in 1983, his Schoolly-D Records was the first artist-owned rap label. It was also the first to release what would be considered a gangster rap song, 1985’s “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?” The booming, self-produced song featured Schoolly D rapping about smoking weed, driving a Mercedes, buying cocaine, pulling a gun on another rapper, hijacking said rapper’s show, and taking a girl (who he later determines is a prostitute) home, where he “fucked her from my toes to the top of my head.”

The way Schoolly D rapped—with an ominous, off-kilter flow—stood in stark contrast to the other rappers of the era. Ice-T, for instance, remembers being drawn to the song the first time he heard it. He was at a club in Santa Monica, California, and was initially hooked by the beat, but he was also taken aback by how Schoolly D flowed.

“At that time, everybody was yelling on records,” Ice-T said. “The cadence was so different.”

As an artist, Schoolly D had taken several significant steps with “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?” For one thing, he stood apart from most of his rap contemporaries because he was a solo artist. In 1984 and 1985, many of the biggest rap acts, including Run-DMC, Whodini, and the Fat Boys, were groups. Another distinction was that he rapped in first-person narrative, and in a brash, violent, sexual, and menacing way, about the street lifestyle.

“Our first inkling of gangster rap was Schoolly D, ‘P.S.K.,’” platinum rapper-producer and Compton, California, gangster rap act DJ Quik said. “I don’t know how I got that record. But I know that once I got it, I couldn’t let it go. I played that shit wherever I could play it. The music kind of low-key scared you into liking it, like a bully.”

As the song gained popularity, Schoolly D noticed that his artistic stance made some listeners uncomfortable, especially coming from a black man who was willing to exact violence on others.

“Richard Pryor would say this all the time: ‘If the shit I was saying had music behind it, it wouldn’t get played, not anywhere, because the message with music and a black man who didn’t give a fuck—or gave a fuck—was dangerous in America,’ and is still dangerous to this day,” Schoolly D said. “You see it. How the fuck are police officers—and twenty of ’em—with guns afraid of one little black boy? What do they say? ‘I was in fear of my life.’ But they don’t give a fuck about going in the hoods and rounding up gangs, but they swear to God it’s always that one motherfuckin’ black dude that’s getting shot.”

Violence notwithstanding, in the “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?” narrative, the protagonist decided he “ain’t doing no time” and showcased his so-called “educated mind” in deciding not to shoot the “sucker-ass nigga trying to sound like me.” Philadelphia was emerging from a neighborhood gang era when Schoolly D was crafting the song, and he said it was this short-lived period of peace and civility that inspired him to look at his city’s culture of violence from a mindful perspective.

“I felt in ’85, when I was writing that, I was feeling like, ‘Wow. We can actually go into other neighborhoods and don’t have to worry about getting shot. We can date other girls from other black neighborhoods,’” Schoolly D said. “It was kind of like I felt like we were educating ourselves. I was like, ‘I’m not going to do no time just for some sucker-ass shit. If I do time, it’s going to mean something.’ That’s what I was trying to stress, but the more I said that, the more it got drowned out. People were like, ‘Yeah. But you said this in the beginning. . . .’ I’m like, ‘Did you read the whole fuckin’ book?’ It made me very angry and it made me close up. So it was just like, ‘People don’t really want to know the real truth. They just wanna know I could shoot and stab, or rape and murder.’ It’s a shame that it has to be that way, but it’s not all that way.”

“P.S.K. What Does It Mean?” also sent shock waves throughout the music world thanks to its thunderous self-produced beat. Unlike most other rappers, Schoolly D produced and composed his own music. He grew up listening to jazz and funk, and he gravitated to songs with lengthy guitar solos and robust horn sections. Material from Ohio Players, James Brown, Chicago, and the Beatles were among his favorites. While listening to these musically disparate groups, he appreciated the instrumental portions of songs. Thus, “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?” contains several extended instrumental sections during its six-plus minutes.

“The song was about not just rapping,” Schoolly D said. “It was also about the music. Since I was going to write the music and the music was going to represent me, I spent a lot of time writing that music.”

It “sounded like a church cathedral eight city blocks big,” Questlove said of “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?” “That much echo. I was more hypnotized at the way the drums kept coming in offbeat at the top of each phrase ending.”

“It was groundbreaking, the drums that they used,” independent rap juggernaut and Kansas City rap pioneer Tech N9ne said. “You never heard anything like that before.”

The influence of “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?” resonated for years. It is one of the most sampled and referenced songs in rap history. The sonically sparse song is a genre-shifting piece of art that influenced generations of artists, even though it never went gold or platinum, and even though it is not often referenced by the artists who appropriated it. In fact, many of the artists who used “P.S.K.” were far more commercially successful than Schoolly D.

For instance, in 1991, the popular UK rock group Siouxsie and the Banshees co-opted the beat on their biggest hit single, “Kiss Them for Me.” In 1997, the Notorious B.I.G. covered it on “B.I.G. (Interlude),” a cut from his ten-times platinum Life After Death album. More recently, Nicki Minaj emulated Schoolly D’s flow on “Beez in the Trap,” her 2012 single featuring 2 Chainz.

Part of the allure of “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?” can also be traced to P.S.K., an acronym for the Park Side Killers gang with which Schoolly D was affiliated. Although Schoolly D never rapped about being in the gang on the song, word spread through rap circles that Schoolly D was representing and flaunting his gang membership, adding another layer of mystery, intrigue, and menace to the selection.

“I was like, ‘Okay, so this is like a little anthem for a gang,’” Ice-T said.

Also included on the “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?” single was another one of Schoolly D’s most significant songs, “Gucci Time.” On this cut, the Pennsylvania artist opens the track by saying he wants to beat people up for biting his material. For many young rap listeners, it reminded them of what they’d hear on the streets.

“C’mon, man, that’s gangster shit,” Tech N9ne said. “That’s like real people talking to you on a dope-ass hip-hop beat. His tone was like nobody’s. He’s the pioneer of gangster rap.”

In fact, the way Schoolly D rapped about his wealth, his material possessions, and his unflinching attitude and willingness to beat people down separated Schoolly D from other rappers.

“‘Lookin’ at my [sic] Gucci, it’s about that time,’” Tech N9ne said. “He had a Gucci, not looking at some other nigga’s Gucci wishing [he] could have one. It reminded me of the dope dealers in the hood. I was like, ‘He must be a dope dealer.’ That was my first stereotype of Schoolly D. He struck me as somebody who didn’t have to talk about nobody else or what they seen. It’s what he’s doing.”

The third “Gucci Time” verse features Schoolly D rapping about pulling a gun on a pimp whose girl he was enjoying himself.

Reached in my pocket / Pulled out my gun / Shot the pimp in the head / Motherfucker fell dead / But now she in jail on a ten-year bid

Like “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?,” “Gucci Time” quickly became one of the most sampled songs in rap history. The first major usage came on Beastie Boys’ “Time to Get Ill,” a selection from Licensed to Ill, their breakthrough 1986 album that sold more than ten million copies. Other rap artists either just recited the chorus—“Lookin’ at my Gucci it’s about that time”—or modified it for their own personal fashion sensibilities, from Common—then going as Common Sense on 1994’s “Chapter 13 (Rich Man vs. Poor Man)”—to the Big Tymers—on their 2002 hit single “Still Fly.” JAY-Z rapped over the instrumental, referenced the lyrics, and was inspired by the title for his “Looking at My S Dots,” which celebrated his 2003 Reebok deal.

Buoyed by the success of “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?” and “Gucci Time,” Schoolly D released his eponymous debut album in 1985. The six-track project also included “I Don’t Like Rock ’N’ Roll,” “Put Your Filas On,” “Free Style Rapping,” and “Free Style Cutting.” The latter was an instrumental selection that featured the turntable work of Schoolly D’s DJ, DJ Code Money.

SAMPLERS VS. INSTRUMENTS

In the mideighties, most rappers moved away from using live instruments to make their music. Instead, they worked with drum machines, samplers, and turntables. This evolution largely eliminated musicians and instruments from the actual music-making of rap. Now, producers and production crews were self-contained units who could program, sample, and scratch their way from an idea to a beat.

KEY EQUIPMENT

DRUM MACHINES

Roland TR-808

Linn LM-1

TURNTABLE

Technics 1200

SAMPLERS

E-mu SP-1200

Akai MPC60

Akai MPC2000

On “I Don’t Like Rock ’N’ Roll,” Schoolly D marked a line in the sand, distancing rap—and himself—from rock music. He also dissed Prince (who, in the eighties, had said that people who made rap weren’t musicians, among other slights), boasted of carrying a .38 automatic pistol, and scored himself and his girl of the moment some marijuana.

Like “Gucci Time,” “Put Your Filas On” is a celebration of the type of ghetto fabulousness that would become synonymous with rap within a few years. It was also a nod to the line of athletic gear particularly popular with drug dealers in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States at the time.

“The fuckin’ label was handwritten. There was nothing pretty about this shit.”

BIG BOY

Original hand-drawn art from Schoolly D.

Released in 1985 on Schoolly-D Records, Schoolly D marked several turning points for rap: It was released by a rapper not from New York and by his own record company. It was also self-funded and self-produced, Schoolly D hand-drawing his own art for his early singles and albums and printing the song information on his releases.

“The fuckin’ label was handwritten,” Los Angeles’s Real 92.3 radio personality Big Boy said. “There was nothing pretty about this shit.”

Schoolly D also provided rap with its first look into the life and mind of an artist who was part of the street culture and boasted about his criminal activity—instead of just describing the deplorable conditions surrounding him.

“When you heard it, it was some of the most gulliest, gutter—to this day—gangster shit that you heard,” Big Boy said. “That’s the way we were talking. If we were on some, ‘Fuck this motherfucker,’ then to hear someone on record say, ‘Fuck this motherfucker,’ you were like, ‘Oh, shit.’”

Unlike other rappers who wanted to distance themselves from urban squalor, Schoolly D placed himself in the middle of it, making it clear that he was representing the streets because he was of—and from—the streets he was rapping about. He made himself the prototype for gangster rappers.

“Being from Philly and being from the Northeast, I had to make sure [to put] more heart and soul into it,” Schoolly D said. “When you put more heart and soul into something like that, people are more afraid. . . . I was representing a person, a one-minded person, Schoolly D, and that’s more dangerous than a gang. It is because you beat down the leader of a gang, the gang disbands. You beat down a man, he becomes a martyr.”

TODDY TEE

Released in 1985, Toddy Tee’s “Batterram” documented the vehicle—a modified ex-military tank outfitted with a battering ram affixed to the front—the Los Angeles Police Department used to break down the doors of suspected L.A. drug and crime houses in the eighties. The song’s upbeat, keyboard-driven sonics belied the horror described in the lyrics, including the batterram, which shoved a person’s living room into his den. The following year, Toddy Tee, who was from Compton, and Mix Master Spade detailed the drug epidemic ravaging South Los Angeles on “Just Say No,” a song whose music was decidedly upbeat for such bleak subject matter. “Batterram” and “Just Say No” hinted at what gangster rap would become.

In 1986, Schoolly D released the first version of Saturday Night! – The Album. Originally consisting of seven songs, the project’s cover art was again drawn by Schoolly D, but, unlike his previous work, Schoolly D’s name was written without a dash between the y and the D. Being essentially a one-man shop (record company owner, rapper, producer, drum programmer, keyboardist) afforded Schoolly D little time for quality control over the artwork he created for his material. He also provided another explanation for the discrepancies between how he wrote his name, which also included writing it with one L—“Schooly D.”

“When you put more heart and soul into something like that, people are more afraid.”

SCHOOLLY D

“In the beginning, it depended on how much weed I was smoking,” Schoolly D said. “Sometimes you’d be seeing double and you think you put those two Ls down, but you know you didn’t. Then I was like, ‘Whoa. It must mean something.’”

Interested in seeking out the possible significance of using Schoolly D versus either Schoolly-D or Schooly D, he spoke to a mystic.

“She was like, ‘I’m going to tell you something about numerology,’” Schoolly D said. “She said, ‘I was thinking about you. I was hoping I’d meet you and sit down with you. When you spell it with the one L, you’re going to do great things at home with your family. When you spell it with the two Ls, great things will come to you with your business, your money. You should think about when you did this and when you did that.’ It was some numerology, but most of it was how high I was.”

Saturday Night! – The Album’s selection “Saturday Night” contained what was becoming Schoolly D’s signature storytelling style: violent, profane tales about his drug-induced, sex-chasing life on the streets of Philadelphia. Like “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?” and “Gucci Time” before it, “Saturday Night” became a popular sample source. The Roots used its music on their 1999 song “Without a Doubt,” and Diddy protégé Loon used the “Saturday Night” instrumental as the music for his 2003 single “How You Want That.” Method Man also paid homage to “Saturday Night” on his hit 1995 single “I’ll Be There for You/You’re All I Need to Get By” with Mary J. Blige by saying Schoolly D’s “cheeba cheeba, y’all” chant.

With Saturday Night! – The Album continuing the success Schoolly D had enjoyed with his self-titled debut album, he embarked on several tours throughout the United States and Europe. When he returned after an extended stay promoting his material in Miami, his mother told him he needed to sit down and call an emerging rapper who had tried to reach him several times. The resulting phone call inspired gangster rap’s first West Coast superstar to make music unabashedly on his own terms.