Buena Vista

COLONEL JOHN HARDIN was tired of Texas, tired of marching, and tired of drills. It had been only a month since he had assumed command of the First Illinois Volunteers. Since then, Brigadier General John Ellis Wool, the commanding officer of the Central Division, or the Army of Chihuahua, had taken note of Hardin’s ability to lead, and immediately after his arrival in August had given him the command of the Second Illinois as well as the First. After a 160-mile march from the coast, Hardin’s Illinois regiments reached Camp Crockett, outside San Antonio. The once-lively city was decaying and nearly deserted. Hardin wrote his sister that he felt as though he had landed in “the most out of the way place in the world.”1

There the Illinois volunteers waited, along with regiments from Kentucky and Arkansas, for orders to move to the front. “There is much monotony in camp life,” Hardin admitted in a letter home to Sarah. The food was bad, the weather worse, and his men were growing antsy. The nearby ruins of the Alamo beckoned, but pilgrimages to the most holy site of the Texas Revolution only stoked the men’s desire to meet their enemy.2

San Antonio was a desolate place, but it offered every temptation for a young man to get into trouble. Hardin, a temperance advocate with no more taste for cards than for whiskey, had “trouble stopping drinking and gambling” among his men, but his vision of himself as a great leader did not extend to dealing with the endless squabbles and differences that seemed to plague the “wild young men” of his regiment. “I get along with my command as well as I could expect, considering the incongruous materials of which it is composed,” he wrote his wife from camp, “but still I have more difficulty in settling other peoples troubles than with anything else.” Reports of unruliness among Hardin’s volunteers had already appeared in newspapers in Boston and Milwaukee.3

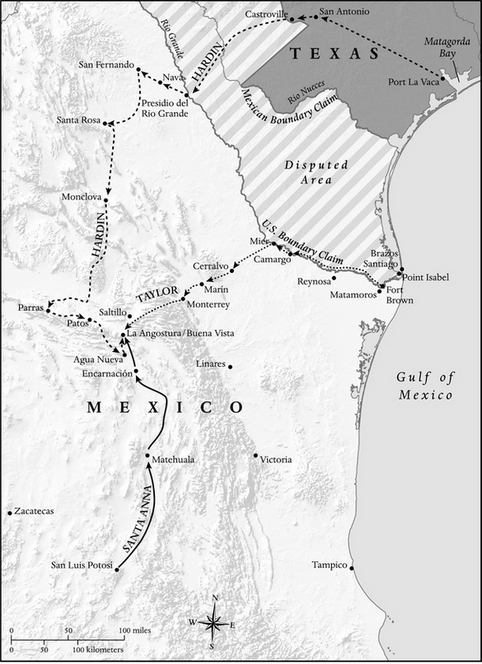

GENERAL TAYLOR AND COLONEL JOHN J. HARDIN IN TEXAS AND MEXICO (photo credit 7.m1)

They sat at Camp Crockett just long enough to miss the excitement in Monterrey. Hardin was livid and blamed his commanding officer. General Wool, a New Yorker and veteran of the War of 1812, appeared to Hardin to lack the needed vigor for the job at hand. “Expect nothing great or striking from this column of the army—it moves with too much of the pomp & circumstance of war & far to stately to overtake Mexicans,” he fumed to his law partner. But Wool was waiting for instructions from Taylor, who himself was waiting for instructions from Polk. Those instructions failed to materialize. Taylor, already overwhelmed by the “lawless” volunteers from Mississippi and Texas, was in no hurry for Wool to bring more to the front. In August, he expressed the idle wish that the two Illinois regiments in Texas “be sent to some other” place.4

Hardin’s daughter Ellen, who had trouble imagining Mexico when her father first departed, now repeatedly saw it in her sleep. She wrote him that August, “Last night I dreamed that you and all your men came back but were raving mad because you did not get to fight the Mexicans.” The eldest of the Hardin children, Ellen understood her father quite well. At the end of September, they finally received orders to march to Mexico. “I start to seek my destiny beyond the Rio Grande,” Hardin rejoiced. “What it may be is uncertain, but I would like to help to form it myself.”5

On the first of October, Hardin and his men began their arduous march to Mexico. Each man carried a knapsack full of food, a tin cup and plate, a spoon, a small table, and a “bread board” to sit upon. They also carried two blankets that would provide their bedding during the march; one blanket served as a mattress, the other as a covering. Each company had a mule-drawn wagon carrying equipment. In addition, the officers had servants to carry their knapsacks.6 Personal servants were considered invaluable for maintaining the respect due officers, who were, by law, gentlemen. The federal government reimbursed officers for servant hire and provided them a clothing allowance and extra rations. The army also specified how many servants each officer class was entitled to bring with them. Generals Taylor and Scott were each entitled to four servants, and each brought four. Colonels were entitled to two, but John Hardin brought only one.

Most of the servants taken to Mexico were African American. Although the army excluded all black men from service in the 1840s (the navy imposed a 5 percent quota), and militia companies also forbade the membership of black men, servants were part of every American army unit, a fact that received no publicity at the time. Officers in Mexico hailing from the South brought their slaves with them, and many northerners either hired freed slaves or attempted to obtain Mexican help once across the border. When Lieutenant Ulysses Grant was ordered to the Rio Grande with Taylor in 1845, he wrote his fiancée, Julia, “I have a black boy to take along as my servant who has been to Mexico.” Colonel Robert Hunter, a Louisiana state senator who volunteered in May despite promising his wife, Sarah Jane, in April that he would never “serve the people” again unless it was “for money and not for honor,” brought his slave Milly with him to Matamoros. Sarah Jane Hunter told Milly to take “good care” of her husband before she sent her to Mexico. Like other servants, Milly shopped and cooked for Hunter, cared for his horses, cleaned his clothes, and ministered to him when he was ill.7

While there is anecdotal evidence of black soldiers following volunteer units and fighting in battles alongside whites, it more frequently happened that black servants took up arms out of necessity. One of Taylor’s slaves told a historian some years later that he saved the general’s life at Monterrey. “A Mexican was aiming at the General a deadly blow, when he sprang in … and slew the Mexican, but received a deep wound from a lance.”8

John Hardin’s servant was most likely a slave from Kentucky named Benjamin, who was around twenty-one years of age. Hardin purchased Benjamin, described as a light-skinned “mulatto boy,” as a personal servant from Mary Todd’s Kentucky relatives in 1833. He was offered Benjamin’s entire family but chose instead to separate Benjamin, described at the time as “too small to ride … far on horseback,” from his mother and siblings. Benjamin was one of several African Americans working in the Hardins’ Jacksonville mansion at the start of the war. The Hardins brought slaves with them when they moved from Kentucky in 1831 after their marriage, and others were left to the couple when Sarah’s mother died. Although they lived north of the Mason-Dixon Line, the legal status of these African Americans was far from clear.9

Illinois was, of course, a free state. It was formed out of territory designated free in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. But particularly in southern Illinois, slavery was very much a reality. According to law, adult slaves became free when they moved to the state. Those under age passed through a period of indenture before earning their freedom. In reality, however, a form of indenture not unlike slavery was the norm in southern Illinois among adults as well as young people. African Americans in Illinois were usually coerced into signing indenture contracts for years at a time. They could not leave the service of their master, could be whipped if disobedient, and were even referred to in legal statutes as “slaves.” Many of these individuals were sold back into permanent slavery before their indentures expired.10

There is little evidence of African Americans in Illinois becoming free after their period of indenture was up, but there is evidence that African Americans with the legal status of slaves were still living in the state at the beginning of the U.S.-Mexican War. The 1818 state constitution outlawed the importation of slaves into Illinois but did not free the slaves already there; in 1840 there were still 331 listed in the federal census. The Hardins purchased an eight-year-old girl named Dolly in the mid-1840s, around the same time that the Illinois State Supreme Court declared that slaves could no longer reside in the state. Dolly signed her mark to a ten-year indenture contract, but she was still working for Sarah Hardin decades later. She was, in fact, buried with the family.11

The fact that Illinois sent more volunteers to Mexico than any other “free” state, indeed more than any other state except Missouri, may have had nearly as much to do with its coercive labor system as it did with the fact that it was a western state, full of believers in Manifest Destiny who themselves had moved west looking for opportunity. “Illinois … should not be numbered with the free states,” the Liberator declared in 1854. “It is, to all intents and purposes, a slaveholding state.” It is not surprising that many white men in Illinois had less of a problem with a war that could enlarge the area of slavery than did the white men of Massachusetts or Ohio.12

John Hardin was far from the only wealthy man in Illinois exploiting the state’s indenture statutes in order to provide his family with the comforts of servile labor. If anything, the Lincoln family’s unwillingness to employ black indentured servants set them apart from other upwardly mobile families in the southern half of Illinois. While there is no need to account for Abraham Lincoln’s unwillingness to engage in coercive labor, it is worth pointing out that Mary Todd grew up in a slaveholding family and certainly could have imported slaves from Kentucky as the Hardins did, had she wished. The fact that she did not may have reflected her father’s evolving antipathy for slavery, a view he shared with his good friend Henry Clay, as well as her husband’s.13

The embedded journalists who traveled to Mexico frequently condemned the country’s system of debt peonage, which produced an underclass trapped in lifelong involuntary servitude because of debt. But those journalists virtually never mentioned the ubiquitous servants of American officers unless they committed a crime or, as more often happened, deserted to Mexico. So many crossed the river when Taylor was camped opposite Matamoros that one Kentucky officer concluded, “If we are located on this border we shall have to employ white servants.” The image of the hearty American volunteer headed to Mexico in order to secure the honor of his country and to gain new territory for America’s free institutions left little room for the hundreds of employed and enslaved African Americans who served their needs. Nor did John Hardin mention Benjamin (assuming that the unnamed servant traveling with him was the same personal servant he had purchased fourteen years earlier) in any of his letters home. Just as slavery in Illinois remained invisible to most white Americans, so too were the black servants in Mexico “invisible” to the public.14

Even with Benjamin’s help, Hardin found his trip through the Nueces Strip quite a trial. The area was as foreboding as ever. Hardin kept a diary, noting that “after crossing the Nueces the quality of the soil & the appearance of the country changed very much for the worse … rattle snakes, wolves, and turkey abound. This land is worth nothing.” The area near the Rio Grande Hardin found particularly “desolate” and rightly attributed it to “the invasions of the Comanche Indians, who … drive off or killed the inhabitants.” He noted that “the Mexicans are very much afraid of the Indians & along the Rio Grande complain justly of their government that it affords them no protection against Indian incursions.” Hardin was traveling through a man-made “desert,” the product of ten years of devastating attacks by Indian warriors on the Mexican inhabitants of the region that depopulated settlements and inhibited economic growth. The easy conquest of northern Mexico by U.S. forces was in large part attributable to the power that Native American people held in the area; the Mexican residents had neither the energy nor the will to fight two wars at once, particularly since one of the wars was against a country that promised to protect them from their more immediate enemies, “the barbarians.”15

Water and grass were scarce, the soil parched. A greater contrast to the well-watered prairies, groves of trees, and fertile ink-black soil of central Illinois could hardly be imagined. And there was little to break up the monotony besides the men’s own hopes for adventure. On October 16, Hardin and his men marched twenty-four miles without locating water. It was a relief to reach the neatly laid-out mining town of Santa Rosa, which boasted an attractive central square. In this town of twenty-five hundred, Hardin purchased trinkets for his wife and children: a “Mexican blanket and cushion” and “a small hand bag … with a silver crop appended to it, & which was attached to a string around a Mexicans neck. It was very tasteful.” Three weeks and 150 miles after leaving San Antonio, they finally made it to Monclova in Coahuila, another orderly town that was home to eight thousand residents. And there they waited, again.16

Hardin was desperate to see action. Convinced that Wool preferred drilling to battles, he wrote directly to General Taylor, requesting a transfer to Taylor’s command. Taylor refused his request and admitted to Hardin that he himself was under orders from President Polk to stay put and remain on the defensive. The president had a new plan for achieving victory over Mexico, and it did not include Taylor, Wool, or the Illinois regiments.

Polk’s snub of Taylor was deliberate. Envious of the general’s growing political prestige, and furious that Taylor had agreed to an armistice with Mexico, the president stripped Old Rough and Ready of four-fifths of his troops, including almost all the veteran forces, and transferred them to the new commanding general of the army, Winfield Scott. Taylor lost his closest advisors and skilled officers: Ethan Allan Hitchcock, Ulysses S. Grant, and other men who had been with him since they first marched into Texas.

Scott had an audacious campaign plan: he would invade the very heart of Mexico. The navy would transport U.S. troops to the Gulf Coast port of Veracruz. They would storm the strongest fortress in the Western Hemisphere and then march directly to the capital. It was the same route that Hernan Cortés had taken in 1519, on the way to conquering the Aztec Empire, although Montezuma lacked Mexico’s artillery and garrisons.

Taylor would play no role in any of it. Polk had slapped Taylor down, in no uncertain terms. Taylor was certain that the intention behind the “outrage” of pulling his troops was “that I would at once leave the country, in disgust & return to the U. states which … would have been freely used by them to my disadvantage” politically.17 Polk might only serve one term himself, but he was determined to keep a Whig from inheriting the White House. His orders to Taylor had the merit, in his eyes, of discrediting Taylor both as a general and as a political candidate.

Not that General Scott was any great friend of the president’s. Yet another presidential hopeful from the Whig Party, Scott was almost six and a half feet tall, of enormous girth, and remarkably patronizing. None of this endeared him to the diminutive president. As Polk fumed in his diary, “These officers are all whigs & violent partisans, and of having the success of my administration at heart seem to throw every obstacle in the way of my prosecuting the Mexican War successfully.”18 But at the moment Scott was the lesser of two evils.

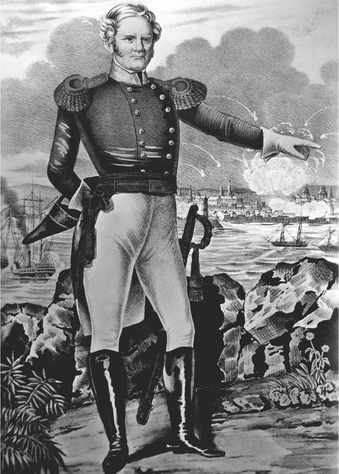

Major General Winfield Scott at Vera Cruz, March 25, 1847. Lithograph by Nathaniel Currier, 1847. “Old Fuss and Feathers” looks neither old nor fussy in this heroic representation of his siege of Veracruz. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. (photo credit 7.1)

Taylor, humiliated and angry, was left with the shell of an army holding a defensive position outside Monterrey. Polk’s need to micromanage everything, and the disrespect he showed to General Taylor, won him no friends in the army. Henry Clay Jr., serving on Taylor’s staff while he recovered from his riding accident, expressed the feelings of most of Taylor’s junior officers about the transfer of troops when he wrote home to his father, “This Army sympathizes with him. For one I must confess I consider the manner of the thing very improper to say the least.”19

Colonel Clay didn’t know it, but his father had dined with General Scott in New Orleans while Scott was en route to Mexico. Clay fled Ashland for the winter, in search of warm sun and some distance from his crushing familial commitments. The tubercular flare-ups that Clay referred to as his chronic “colds” and his son John’s continuing mental struggles left him incapacitated at the close of 1846, and both he and Lucretia worried incessantly about young Henry in Mexico. Clay sought a geographic cure in New Orleans. He always felt better in the Crescent City.

Clay stayed, once again, at the home of Dr. William Mercer, and while the doctor’s high-ceilinged mansion was as comfortable as ever, New Orleans seemed somehow washed-out. The weather was terrible. Clay wrote Octavia LeVert that the city seemed “less gay” than usual, and he attributed it to the war. But certainly Clay was less gay than he had been in the past. The optimism and overwhelming self-confidence of candidate Clay just before Valentine’s Day in 1844, when he strolled the streets of New Orleans convinced the presidency was in hand, were gone. “This unhappy War with Mexico fills me with anxious solicitude,” he wrote not long after arriving in New Orleans. “When is it to terminate? How?”20

The commanding general’s visit provided Clay a singular opportunity to assuage his fears. They dined at the Mercer home, and given the love of elegant dining, fine food, and wine that Clay and Scott shared, it was no doubt a lavish repast. Almost certainly the two men discussed Henry Clay Jr.

Three days later the elder Clay was invited to deliver a toast at a dinner in the company of several military men. Attempting to make a joke out of a very serious matter, the Sage of Ashland admitted that he “felt half inclined to ask for some little nook or corner in the army, in which I might serve in avenging the wrongs to my country.” The applause of his listeners encouraged him. He announced to even greater whoops and cheers that “I have thought that I might yet be able to capture or to slay a Mexican.” Of course the aged Clay was not about to join the army; he was referring, with apparently indiscernible sarcasm, to the early enthusiasm for volunteering. Clay concluded his toast with his sincere hope that “success will crown our gallant arms, and the war terminate in an honorable peace.” Clay’s remarks were reprinted in the New Orleans Picayune the following day and were quickly picked up by newspapers of every persuasion.21

While Prince Hal’s spontaneous and thoughtless remarks hardly reflected his true feelings about the war, this toast was the first public statement he had made about Mexico, and almost no one got the joke. Not that it was very funny. “What will some of his friends in Congress say?” asked the Democratic Mississippian. What they said was that it appeared the great Henry Clay was pandering to public opinion, inflaming bloodlust at the very moment that the nation appeared to be tiring of the war. “Poor stuff,” pronounced the Journal of Lowell, Massachusetts, while the Quaker-edited Worcester Spy conceded, “If Henry Clay is possessed of the blood-thirsty spirit therein shadowed forth, then he is not the man we have ever taken him to be.”22

Democrats reveled in the gaffe. “The Federal [Whig] papers of New England continue to throw out their bitter denunciations on account of the present war with Mexico,” one Vermont Democratic paper crowed. “Their slang seems to correspond poorly with the views of the great ‘HENRY’ … at a late dinner at New Orleans.” Abolitionists pointed to the gaffe as evidence that they had been right to forsake Clay in 1844. “The whole history of his life,” the Emancipator wrote, proved “that he was too demon-like for any christian man to support without sin.”23

Papers were still debating Clay’s toast on Valentine’s Day of 1847. Clay had imagined what it would be like to be on the front, but on that day many of the volunteers found their minds wandering in a very different direction. Twenty-seven-year-old Thomas Tennery mused in his diary, “This being Valentine’s day no doubt the young folks at home are employing it in making love, or visiting, or receiving company, and making merry.” This was as it should be, since “it is the duty of all nature to enjoy the time as well as possible.”24

The state of Coahuila was full of Americans desperate to kill a Mexican, and it seemed that most of them were fuming in the Army of Chihuahua. Hardin blamed General Wool for the fact that he hadn’t seen a battle, but in fact Wool was just as anxious to fight as his men were. He was still waiting for orders. In late November 1846, Wool wrote Taylor requesting a move from Monclova to the village of Parras, 125 miles west of the colonial town of Saltillo. “Inaction is exceedingly injurious to the volunteers,” Wool wrote Taylor, “I hope the general will not permit me to remain in my present position one moment longer than it is absolutely necessary.”25 The subtext would have been clear to Taylor: the volunteers were out of control, and Wool feared for the safety of local residents.

The volunteers needed to move on, and gathering the greatly diminished army in the five-thousand-person town of Parras, a spring-fed oasis in the semidesert of Coahuila, made sense. The climate was “unsurpassed in the world,” according to one volunteer, with air “so pure that flies and mosquitos are unknown.” Famous for its wine and women (“Such enchanting glorious eyes! and black glossy hair! What little feet and hands and divinely graceful shapes!”), Parras may not have been the safest place to house the troops.26 But it both fit within Taylor’s plan to control northern Mexico defensively and also guarded against a possible attack by Mexican forces, which were now under the command of the charismatic General Antonio López de Santa Anna, the one man who could unify, inspire, and lead his diverse and fractured country to victory. And it was all James K. Polk’s fault.

General Antonio López de Santa Anna. Photographic print on carte de visite mount. General Santa Anna held the rank of president of Mexico on eleven separate and nonconsecutive occasions between 1833 and 1855. He was fifty-two years old and living in exile in Cuba when the United States declared war on Mexico. Polk, believing him willing to negotiate with the Americans, allowed him transit back to Mexico. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. (photo credit 7.2)

Like so many Americans, Santa Anna’s first important military service was against Indians, in his case in the land that would eventually become the American Southwest. He quickly rose through the ranks in the army of New Spain, joined the rebels in the independence movement, and became a towering personality in the history of early national Mexico.

After his failed 1836 campaign against Texas (it was Santa Anna who led the charge against the Alamo, ordered captured Americans shot at Goliad, and signed a treaty of Texas independence), he retired in disgrace to his estate, Manga de Clavo, on the road between Veracruz and Mexico City. Manga de Clavo was Santa Anna’s Hermitage, a showpiece property (eventually boasting forty thousand head of cattle) that provided not only a convenient location for meetings of his friends and allies but also physical proof of his status. At 483,000 acres, however, Manga de Clavo was vastly larger than Jackson’s domain. One could travel thirty miles along the main road between Veracruz and Mexico City without leaving Santa Anna’s property.27

But an imposing estate can only do so much to repair a reputation. In 1837 it appeared unlikely that the people of Mexico would ever forgive Santa Anna his incompetence, or forget how quickly he had turned despot a year earlier. Another international crisis soon returned him to his countrymen’s good graces, however. In 1838 the French landed in Veracruz in an attempt to force repayment of Mexican debt. Santa Anna rode to the port from his estate, led Mexican forces against the French, and lost a leg in the process. He appealed to the people of Mexico to forgive his mistakes and grant him “the only title I wish to leave for my children: that of a good Mexican.” Santa Anna’s heroic self-sacrifice in the “Pastry War” catapulted him back into power. But after another dictatorial stint as president, Santa Anna was imprisoned, then banished to Cuba in June 1845.28

To Americans raised on stories of the Alamo, Santa Anna was as pure a devil as walked the face of the earth. But Polk saw things differently; he believed he could manage Santa Anna. Thomas Hart Benton later wrote about the Polk administration that “never were men at the head of a government less imbued with military spirit, or more addicted to intrigue.” From his initial directions to Slidell before the war through the closing days of the conflict, Polk repeatedly demonstrated his faith that secret dealings could bring Mexico to terms. Given Polk’s assumption that Mexicans were cowardly and corrupt, it isn’t surprising that he thought the deposed leader corruptible. U.S. envoys persuaded him that Santa Anna was so desperate to return to power that he would settle on almost any terms the United States might dictate. The president of the United States allowed Santa Anna, Mexico’s greatest leader, free transit from Cuba back into Mexico in August 1846.29

Polk’s faith that the war would be a brief one may have stemmed from his belief that Santa Anna would sell California to the United States once he was back in power. Polk repeatedly asserted, “I am strongly inclined to believe that Santa Anna desires peace, and will be prepared to re-open negotiations as soon as he feels himself secure in his power.”30

Polk operated under the assumptions that Santa Anna was an opportunist and that he was addicted to power. Both were true. But the general was also a patriot, or as he himself had put it, “a good Mexican.” Once safely in Mexico, Santa Anna evinced no interest in negotiating with the United States, and instead promised to avenge the loss of Texas. At first Polk refused to believe it. “Though I have reason to think that he is disposed to make peace, he does not yet feel himself secure in his position, and is cautious in his movements,” he wrote in October. “I have but little doubt but that he will ultimately be disposed to make peace.”31

But in November Santa Anna started organizing troops to confront Taylor’s small army. “Ten thousand rumors reach us that Santa Anna is marching with a large force, some say 20,000 on this place,” Henry Clay Jr. wrote his father. If an army of this size was really marching north, Taylor recognized that their best chance to defeat it was to gather the combined forces of his and Wool’s troops near Parras.32

Before hearing back from Taylor, Wool began his march south, while Taylor, who was directly disobeying orders from Polk to stay where he was, also began to move toward Parras. Hardin was thrilled to be on the move, but he complained to his wife about the “long tedious & tiresome march” and the weather along the way: “extremely hot in the middle of the day, the nights are quite cold.” They reached Parras on December 5. The Illinois volunteers had marched seven hundred miles since they first landed in Texas. They had yet to see action, and Hardin was shocked by the poverty and desolation of northern Mexico. “Occasionally a Hacienda is found in a day’s march, on a small stream but beyond all is ‘a vast howling wilderness’ yielding nothing for the support of man or beast,” he wrote his wife. “Not an acre in 100 is or ever can be worth a cent in all Mexico we have traversed.”33

Sad to say, they seemed no closer to a fight in Parras than they had back in Texas. “We have supplies of wheat here for 4 months for 3000 men, & of corn for 2 months & of Brandy and rum for 10 years,” Hardin complained to David Smith, his fellow temperance advocate. The troops were getting restless, and to Hardin’s dismay, “our men use the liquor rather freely when they get a chance.”34 General Wool ordered Hardin to post a guard to prevent the “plundering” of Mexican civilians in the vicinity. Hardin took offense at the “imputation” that his men were stealing, or worse. Wool backed down: it wasn’t the Illinois volunteers he was worried about, “it was the Arkansas troops.” But the damage was done. Hardin threatened to march his men home—an idle threat. Wool said he would be happy to see Hardin leave, “but your men cannot, and shall not go.” If there was ever any question in their minds, the volunteers of the First Illinois now realized they were stuck in Mexico for the duration of their yearlong enlistment.35

Henry Clay Jr. faced similar problems with his own troops camped nearby. According to one publicized report, the men of the entire Second Kentucky “were incompetent from inebriation,” although Clay assured his father that the reports were overstated and that, upon his “honor,” he himself was sober. “My own habits have not for years been so good as during this campaign,” he wrote his namesake, assuring him that he had “not for a single moment been incapacitated for my duties” by alcohol. But Colonel Clay admitted that the strain of keeping the Second Kentucky volunteers in line was “making me prematurely old. I long for a battle that it may have an end.”36

As they sat in camp Hardin’s patience began to wear thin. He had not received a letter from his family since September. He wrote to Smith in early December, “I have seen a good deal of the world since I left home.… I want now to see a squirmish, a fight & a battle, & then will be ready to go home & attend to other business than arms, unless there is a call for troops at home.” His feelings were nearly universal among the soldiers gathered in northern Mexico under Wool’s command. Archibald Yell, a disciple of Andrew Jackson’s and close ally of Polk’s since the 1830s, gave up his congressional seat to lead the First Arkansas Volunteer Cavalry to Mexico in 1846, only to wait around in camp. He wrote Polk in early November that “I now dispare of being able to do my country much service or myself much credit—I wish to God I was with Kearny or Taylor but so it is my destiny is sealed, and without remedy, I never murmur, but posibly the time may come when I can expose the folly and imbecility of this collum.” Captain Robert E. Lee of the Army Corps of Engineers, just weeks shy of his fortieth birthday, also worried that his “ambition for battle would be permanently thwarted” by the bad luck of being assigned to Wool’s division.37

Noting the great “dissatisfaction in his com[man]d,” Taylor admitted at Thanksgiving that “Genl Wools column had turned out an entire failure, which, I expected from the first would be the case.” Taylor had, in fact, predicted back in June that the vast number of volunteers being sent to northern Mexico “will from design or incompetency of others, have to return to their homes without accomplishing anything commensurate with their numbers … The question will be asked why did the troops lay idle, & why did they not march against the enemy no matter where he was, find, fight & beat him.”38

Meanwhile, as Hardin’s frustration over “missing” the war grew, he began to question America’s future in the region. Back in October, when he first reached Mexico, he had seen potential for U.S. development. He had written in his diary that the silver mines near the town of Santa Rosa “are reported to be amongst the richest in Mexico.” They were abandoned because of the “ignorance of the Mexicans” but “would require only a little skill and energy to make very valuable.”39 Hardin could easily envision the mines, and territory, in the hands of the United States.

But the longer he spent in Mexico, the less he liked it. He believed the land, for the most part, to be worthless. In early December he wrote David Smith that “there is not an acre in 500 that a man in Illinois would pay taxes on.” The people of Mexico were far worse. “I have never seen a drunken Mexican,” he admitted. “That is the only good thing I can say about them—they are a miserable race, with a few intelligent men who lord it over the rest ¾ of the people, or more are Paeons and as much slaves as the negroes of the South—Treachery, deceit & stealing are their particular characteristic—They would make a miserable addition to any portion of the population of the United States.” A week later he informed another friend that the only difference between the “paeons” of Mexico and “the slaves of the South is, their color, & that the bondage of the father does not descend to the son—as for making these Paeons voters & citizens of the United States, it should not be thought of until we are … to give all Indians a vote.” As for Mexico’s women, they “are not pretty enough to please a man who has not seen a white faced lady for 4 months—in fact, they are generally most decidedly homely.”40

When Hardin had volunteered for Mexico he was infused with ideals of Manifest Destiny. But three months in the country had radically changed his views. “Although I was for annexing all of this part of Mexico to the United States before I came here,” he told a friend, “yet I now doubt whether it is worth it.… So much for Mexico. Its people are not better than the country—not more than 1 in 200 is worth making a citizen of.” John Hardin’s evolution from an avid expansionist to xenophobic cynic was a rapid one. Gone were his early professions of destiny and national greatness. Hardin’s single goal in December 1846 was to see action.41

Hardin’s views were shared by many in the army. The Genius of Liberty, a newspaper published by and for U.S. troops in Veracruz, attributed the dramatic decline in volunteering to soldier disillusionment. “At the commencement of the war … many of us entertained extravagant notions of the country which we were about to invade.… We were to rove in the delicious gardens of the south, basking in the charms of some beautiful maiden as she wreathed the flowers, or offered the fruits of her native soil.… But a few days in Mexico soon dispelled the illusion.… The gardens turned out to be vast forests of palm, maguey and cactus.” Exposure to the land and people of northern Mexico led them to question the future of Manifest Destiny in the region, and with few opportunities to prove themselves in combat, many volunteers wondered exactly why they had signed up in the first place. “A right hard fight with the enemy, followed by a riddance of this pestilent country, would be hailed by the whole regiment as a consummation of too much happiness,” one Georgian volunteer wrote home. “I would willingly forego [sic] the possession of all the rich acres I have seen to get back from this land of half-bred Indians and full-bred bugs.”42

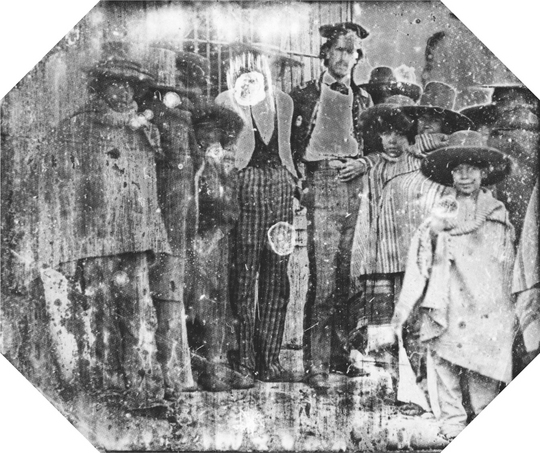

Group of Mexicans with a soldier, 1847. This daguerreotype was most likely taken in Saltillo, Mexico, in the late winter or spring of 1847. The soldier has been identified as Abner Doubleday, the New Yorker who is often said to have created the modern game of baseball while a student in Cooperstown. A first lieutenant in the army, Doubleday was stationed in Saltillo with the First Regiment of Artillery from February 1847 to the end of the American occupation in May 1848. Doubleday spoke Spanish well and showed more sympathy for the people of Mexico than most American soldiers. His irregular uniform reflects the widely varied costumes worn by volunteers. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. (photo credit 7.3)

But soldiers also regretted the deaths of Mexican civilians, the “friendly” inhabitants who “always treated us with kindness,” in the words of The Genius of Liberty. “It is painful for us to reflect upon the fact, that many of those who fell before our invincible soldiers … sacrifice[d] their lives in a warfare which is as inglorious as it is useless.” Of course America was turning away from the war. “A powerful nation may be compelled to prosecute a war with a weaker one, and destroy the innocent with the guilty in order to secure its own rights, but the more civilized its citizens will be, the more reluctantly will they engage with it,” the paper wrote in October. In December Taylor remarked that the volunteers “are beginning to look many of them to their homes with much anxiety, & will leave the moment if not before their time expires.”43 For most of the volunteers, the great adventure in Mexico had turned out to be anything but.

Rumors of Santa Anna’s march increased in early January. Mexican civilians gleefully reported to the American troops that they should expect “mucho fandango pocotiempo” or “a big party coming up soon.” Taylor ordered Wool’s column of the army to a wide valley south of the town of Saltillo, at the base of a mountain pass known as Angostura, or the Narrows. A hacienda named Buena Vista was close by. At last a battle seemed imminent, but again, nothing happened.44

Hardin wrote his daughter Ellen a long and lonely letter soon after arriving at Buena Vista. Ellen, now fourteen, was five years older than her brother Martin, and eight years older than the baby of the family, Lemuel. She was a studious girl whose love of both books and horses had been nurtured by her father. He had taught her to ride before Martin’s birth, placing her on a horse in a great pasture adjoining their home and issuing the warning, “Now my daughter, don’t let him throw you off.”45

The two had been unusually close before he entered national politics. When she was young she “always followed him about, as a little child more frequently follows the mother. He never checked this following and I was in great happiness when sometimes he would take my hand as I trudged about, or would turn and tell me about some object, tree, pond, bird or other animal.” One of her most vivid childhood memories was standing perfectly still in the corner of the family’s sitting room, unseen by the adults, while her father had a bullet removed from his eye after a hunting accident. “I held my breath while the physicians were at work—I thought my father was so brave to utter no sound, that I must not cry, although I seemed to realize his suffering—for even then I had an unbounded devotion to him.”46

The two remained close, or as close as they could be given her father’s repeated absences from Illinois. When they were together they took long rides on horseback. When he was in Congress he talked about bringing her out to Washington “for a few days,” so she could see the “splendid” Capitol and other sights. But it didn’t happen. Ellen was still devoted to her father, however, and although Hardin never put his family before what he saw as his “duty,” he was clearly fond of his daughter as well. “Very gladly would I exchange a few days or weeks of camp life to be by the sides of my sweet children and their mother,” he wrote her.47

He had visited the elegant late eighteenth-century cathedral in Saltillo, famous for its carvings of Quetzalcóatl, the Aztec rain god, and columns of intricately carved gray stone. Like most other Protestants, he was distinctly unimpressed. The church was “gaudy” and full of “contemptable” wax figures. “Just think of the virgin Mary stuck up on the side of the wall over an altar in a glass case looking like the ‘Belle of Philadelphia’ or some other beauty and dressed in the finery of 15 years ago,” he wrote Ellen. “If I could only show you a mountain vista & a church you could see all of Mexico worth seeing & these are much better to look at than to be amongst.” He wistfully admitted to his daughter that Mexico had failed to live up to his imagination. “The rich, beautiful, lovely & Indian, this valley which I expected to find in Mexico & which I thought I might be tempted to live, has not yet been seen.”48

At last he received news from his wife, who was, as he suspected, staying at her brother Abram Smith’s cotton plantation in Princeton, Mississippi. In a long letter, written just before Christmas, she revealed her concern for her husband. “I know you will never knowingly or wantonly commit an act that will make me blush for you or myself and to know that the Father of my children is a man of spoilless character and of unblemished morals is a comfort indeed, now that you are exposed to the demoralizing influence of a soldier’s life.” Sarah had heard the stories of the behavior of America’s soldiers, and while she trusted her husband, she was also frustrated at being left alone. She need not have worried. John didn’t touch liquor, and he appears to have avoided the fandangos that entranced his men.

Sarah resented her husband’s absence, but she was also proud he was no tame, spiritless fellow. He had chosen to go to war. Her brother Abe was another story. He appeared to be “a perfect Patriarch,” she wrote John. Abe was master of a prosperous plantation and owned sixty-one slaves. He had a thriving law business, had served in the state legislature, and had earned a reputation as a Shakespearian scholar of some note. But he had not gone to Mexico. This gave Sarah license to belittle her brother. She confided to her husband that, appearances aside, Abe was “a complete henpecked husband.” Her evidence? “He would like to go to Mexico but his wife wont let him even though he wants to go.”49

Did she wish her own husband were slightly less spirited, or somewhat more henpecked? Between his term in Congress and his service in Mexico, the couple had seen very little of each other over the past three years. The children missed their father, and the boys were running wild. Her brother’s plantation, she complained to John, was “decidedly the last place to raise children.” She felt free to mock Abe in a letter to her husband, but in a moment of anger she wrote her soldier husband, “life is too short to be wasted in the way you are living.”50

John responded in an emotional letter the week before Valentine’s Day. Home seemed very far away to him as well. When he had first arrived in Texas, his mind was still in Illinois. He had been aware that it was election day, and he had mentally framed his duties as a soldier in the context of his previous work as a lawyer and politician.

But in February 1847, that was no longer the case. “I have been so long freed from the noise & hustle of politics & law that I think of them as ‘things that were,’ ” he told his wife. “I feel no distinction to participate in them again—especially is this the case with Politics—Afar off in Mexico in a foreign land we cease to feel an interest in party struggles & only desire to see our Country triumphant & prosperous.” While Hardin’s dreams of Manifest Destiny had faded, he still craved a battle. “I will not conceal from you, what indeed you well know,” he admitted to Sarah. “I am anxious to see more of Mexico, and some real service. If I see that I have accomplished my goal, if not it will have been a year thrown away.”51

What John did not tell Sarah was that only three days earlier he had written Stephen A. Douglas, now a U.S. senator, in the hopes of obtaining a transfer to General Scott’s army. Perhaps he was inspired by the good luck of Robert E. Lee, who learned on the eve of his fortieth birthday that he was being transferred to General Scott’s expedition. Both Hardin and Lee were convinced that glory awaited them in Veracruz.

Hardin told Senator Douglas that if there was any opportunity for him to join the departing soldiers and march to the heart of Mexico, he would grab it. Otherwise he was sure he “would get no battle” and had no wish to continue with his regiment after his term of enlistment ended.52 Rumors of a great Mexican army on the march were, by early February, “so frequent and so groundless” that “we now disregard them,” Hardin admitted.53

A week later rumors were arriving “every few hours” that Santa Anna was “about to be on us with 20,000 men.” But Hardin didn’t believe “one word of the whole story.” His “dull and stagnant” life in camp was only alleviated by the arrival of “many old acquaintances” in Henry Clay Jr.’s Second Kentucky Regiment. Socializing with Clay and the other Kentucky officers provided some distraction, but not enough.54

Hardin had one other matter to write home about: a shocking massacre. At the close of 1846, a sergeant in the Arkansas regiment of volunteers stationed with Taylor’s troops admitted in his diary that “a portion of our Regiment are assuming to act as Guerrillas, and have been killing, I fear innocent, Mexicans as they meet them.” Not long afterward, Mexicans killed an Arkansas volunteer in retribution for a Christmas Day raid on a local ranch at Agua Nueva where Arkansas volunteers robbed and raped the inhabitants.55

On February 13, the Arkansas cavalry took revenge. They rounded up civilians and commenced “an indiscriminate and bloody massacre” of twenty-five or thirty Mexican men in the presence of their wives and children, utilizing tactics learned in Indian wars. An Illinois volunteer named Samuel Chamberlain heard gunshots and rushed to the scene. He later described the shocking sight: “The cave was full of volunteers, yelling like fiends, while on the rocky floor lay over twenty Mexicans, dead and dying in pools of blood, while women and children were clinging to the knees of the murderers and shrieking for mercy … nearly thirty Mexicans lay butcherd on the floor, most of them scalped. Pools of blood filled the crevices and congealed in clots.”56

Archibald Yell, Polk’s friend and commander of the Arkansas “Rackensackers,” as they were now known, refused to discipline the guilty troops; Taylor was ready to send the whole crew home, except that he desperately needed troops. He, unlike Hardin, knew there was a greater battle than this in store for the men of the Army of Chihuahua.

Indeed, Hardin was proved wrong the very day he wrote to Sarah. Through a stroke of luck, General Santa Anna’s troops had intercepted a letter from General Scott to Taylor revealing the transfer of troops from one commander to the other, as well as details of the proposed invasion of Veracruz. Santa Anna could have concentrated his troops in Veracruz and prepared for the American onslaught of central Mexico. But instead he envisioned a singular opportunity to wipe out Taylor and his remaining forces when the invaders were at their weakest. On February 2, the commander marched out of the great mining center of San Luis Potosí, three hundred miles northwest of Mexico City, with an army of twenty thousand men.

Samuel Chamberlain, Rackensackers on the Rampage. Samuel Chamberlain of the Second Illinois Volunteers witnessed the massacre of unarmed civilians by the Arkansas Volunteers on February 10, 1847. His painting of the gruesome scene highlights the violence of the volunteers, who appear deaf to the pleas of women and children. A company of U.S. dragoons at the mouth of the cave has arrived to end the slaughter. Courtesy San Jacinto Museum of History. (photo credit 7.4)

The Mexican army suffered incredible deprivation during the three-week, two-hundred-mile march to Buena Vista. The winter weather was brutal, the desert terrain unyielding. Food, sleep, and water were in short supply. On February 21, Taylor received confirmation that Santa Anna and his army were just sixty miles to the south. He directed General Wool to lay out defenses at La Angostura between a high plateau laced with ravines on the left and a network of gullies on the right. Santa Anna arrived later that day to offer Taylor the chance to surrender. The American forces were vastly outnumbered, Santa Anna told Taylor; surely he recognized the untenable nature of his position. Taylor declined.

The American forces left under Taylor’s command, almost all volunteer, numbered less than five thousand. Santa Anna’s army of twenty thousand had been weakened by the forced march. Perhaps a quarter of his men, a shocking percentage, had died along the route. But the odds were still daunting. Hardin’s regiment, along with a Pennsylvania battery, was stationed in the pass, a mile in front of the other troops. On the frosty morning of February 22, the Mexican forces came into view. Taylor informed Hardin that unless he held the pass, the battle would be lost. Hardin’s moment had arrived. He addressed his men: “Soldiers: you have never met an enemy, but you are now in front. I know the 1st Illinois will never fail. I will see no man to go where I will not lead. This is Washington’s Birthday—let us celebrate it as becomes true soldiers who love the memory of the Father of their Country.” It was a false alarm. The irregular fire that occurred that day did not involve the volunteers from Illinois. Santa Anna gave a moving speech to his troops in the evening, and the strains of his band could be heard clearly by Hardin and his men.57

The American troops woke on the morning of the twenty-third to the astounding sight of the Mexican army celebrating a pre-battle mass. “Twenty thousand men, clad in new uniforms, belts as white as snow, brases and arms burnished until they glittered in the sunbeams like gold and silver,” marveled Illinois volunteer Samuel Chamberlain. It was obvious that the Americans were vastly outnumbered. Santa Anna attacked immediately after mass, and his forces quickly pushed back the U.S. troops and threatened to surround them. By nine that morning Taylor’s small army was in desperate trouble, but America’s light artillery, vastly superior to the Mexican cannon, staved off defeat. The American guns “poured a storm of lead into their serried ranks which literally strewed the ground with the dead and dying,” according to one eyewitness. The Pennsylvania battery deployed alongside Hardin’s regiment held off five thousand troops with artillery, but several thousand more Mexican infantry attempted to flank their position. Hardin took five of his companies and, “himself always in front,” advanced under cover of a hill, shouting, “Remember Illinois! Give them Blizzard, boys!” The infantry was driven back. His soldiers later claimed that that charge saved both the First Illinois and Clay’s Second Kentucky regiment from being flanked.58

A fierce charge by the Mississippi troops, led by Jefferson Davis, combined with the ceaseless efforts of the artillery, drove the Mexicans back by the early afternoon. At 4:00 p.m. Taylor attempted to seize the initiative. He ordered the Illinois men and the Second Kentucky to advance. “This, like all of Hardin’s moves, was quickly made,” and approximately a thousand men pushed ahead, triple-speed, over broken ground in the face of a heavy fire of grape from a Mexican battery. In a frenzy of optimism, Hardin brashly announced, “We will take that battery.” He drew his sword with a shout, and the men of Illinois charged the battery directly behind their fearless colonel.

They almost made it. When they were only a few yards from the battery, “some fifty yards to our right their whole reserve—some six or seven thousand infantry, opened fire.” Hardin had unknowingly rushed into the path of Santa Anna’s final assault. Ten thousand men, including several thousand fresh troops, emerged from a ravine armed and ready to crush the American advance. They advanced across a plateau in a blaze of fire. Many who were there later recalled that “no man but Hardin would have attempted to fight with such odds as 15 to 1.” The men could hear the colonel’s voice above the din, shouting, “Boys, remember the Sucker State; we must never dishonor it! Give them Blizzard! They fall every crack!”59

Hardin’s bluster could not disguise the fact that both he and Taylor had badly misjudged the situation. Because of his ill-considered charge, Hardin’s troops were now beyond supporting distance and were surrounded on all sides by Mexican infantry. His position was untenable. The Second Illinois and Henry Clay’s Second Kentucky pushed forward to support Hardin, and the regiments became the focus of the Mexican attack. “The Mexicans, with a suddenness that was almost magical, rallied and returned upon us,” a participant reported. “We were but a handful to oppose the frightful masses which were hurled upon us, and could as easily have resisted an avalanche of thunderbolts.”60

Taylor called for Hardin to retreat.

“Now came a desperate time,” remembered a survivor of the battle. The men sought shelter in a gorge and had to retreat down a “deep ravine—rocky and broken—in which no order could be kept.” All semblance of discipline evaporated as each man fought for himself. “There were infantry a few yards above us on each side of the ravine, and several thousand lancers had cut off our retreat at its foot.” To the retreating men it appeared that the entire edge of the gorge was darkened by a great mass of Mexican soldiers firing down on them. At this point, “every voice appeared to be hushed but Col. Hardin’s—we could distinctly hear him shout … ‘Remember Illinois and give them Blizzard, boys!’ ” Twenty Mexican lancers charged at Hardin, firing at the same time. A private in his regiment reported that “Hardin fell, wounded; with his holster pistol he fired and killed one lancer—and I think he drew, or attempted to draw, his sword—but in the melee I could not be sure, for as many lancers as could approach him, surrounded, and threw their lances in him—and thus perished an officer, than whom none was ever more beloved.”61

The charge decimated the First and Second Illinois, as well as the Second Kentucky. The three units accounted for 45 percent of the fatalities that day, with ninety-one Illinois men and forty-four Kentuckians killed, and greater numbers injured. At two the following morning, the surgeon attached to the Second Kentucky wrote home to his family that he had “just finished dressing the wounds of my regiment. I have been in blood to my shoulders since 9.00 this morning.”62

In total, more than seven hundred Americans were either killed or injured, including a number of officers, some of whom, like Hardin, had national reputations. Rackensacker commander Colonel Archibald Yell was killed while attempting to counter a Mexican charge in the morning. Colonel William McKee, commander of Clay’s regiment, was also killed in the retreat down the ravine. A sudden rainstorm in the late evening brought the fighting to a close. A rainbow followed. Taylor’s forces had maintained their defensive position, but it was far from clear whether they could continue to do so. Neither commander could claim a victory that night, but the numerical superiority of the Mexican forces argued in their favor come the following morning. Taylor’s little army was far from optimistic at the end of the bloody day of battle. They shivered during the frosty night as coyotes feasted on the bodies strewn across the field.

Remarkably enough, the Mexican army chose not to fight another day. Santa Anna instead decided to retreat under cover of darkness, later claiming that he had been called back to Mexico City to quell a political uprising. In fact, he received no such order. He was almost back to Mexico City when he learned that five national guard battalions, supported by clerics tired of paying for the war, had rebelled against the liberal government.63 Santa Anna had simply had enough. He had stopped the Americans, and his forces had suffered horrific casualties, with more than thirty-five hundred killed, wounded, or missing. But during the day’s battle they captured flags and artillery, and those Santa Anna carried with him back to central Mexico as proof of Mexico’s victory.

Americans, of course, viewed Santa Anna’s retreat differently. Despite being outnumbered and without the help of the veteran troops, they had miraculously prevailed. When news of the victory arrived in the United States, spontaneous celebrations occurred across the nation, in small towns and great cities. When news reached Illinois, church bells pealed and cannon were fired. There were bonfires and parades from New Orleans to Boston. “Flags are flying from all the public buildings, and one universal spirit of joy and gladness pervades all patriotic hearts at the success of old ‘Rough and Ready,’ ” a reporter in New York gushed.64 Printmakers immediately prepared images of the battle for sale, many of which emphasized the intimate and seemingly heroic hand-to-hand nature of the combat.

The Battle of Buena Vista became the signature victory of the war, proof that a small band of brave American volunteers could outfight a Mexican army four times its size. It was immediately conceded that there could be no higher “aspirations of military fame” than to say of a “fellow-citizen, he was at Buena Vista.” From his post as editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Walt Whitman proclaimed that the victory “will live … in the enduring records of our republic,” and that “whatever may be said about the evil moral effects of war,” victory at Buena Vista “must elevate the true self-respect of the American people.” Caroline Kirkland, the editor of a new literary magazine, admitted that even those such as herself who found war “abhorrent and revolting” couldn’t help but feel “pride” for the “gallant self-devotion” of the troops.65

Battle of Buena Vista. Lithograph by Nathaniel Currier, 1847. This popular representation of the American victory at Buena Vista highlights the hand-to-hand combat of the battle. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. (photo credit 7.5)

It was the battle that the volunteers and American public had longed for. Then the casualty lists began to roll in.