War Measures

WHAT POLK FOUND most galling about the cacophony of voices raised against him was that the news from the front was good, remarkably so, and yet he received none of the acclaim. He complained to his cabinet and his diary about “the injustice of giving all the credit of our victories to the commanding General,” and none to the regulars, volunteers, or commander in chief. Even so, he thought, it should have been apparent to everyone that matters in Mexico were progressing nicely.1 General Scott was on the move, the Mexican army was on the defensive, and the plan to take the capital was falling into place.

Scott, like Cortés before him, had stormed Veracruz during Holy Week. Not long afterward, Manuel G. Zamorg, a major in the national guard of Veracruz, bemoaned the fact that “the Conquest of Mexico, to judge from present indications, was far harder to Cortez in 1521 than it is to the Yankees in 1847. What a miserable reflection!” Scott set off for Mexico City after securing Veracruz in April. He understood that there was no time to rest, or to lose sleep over the collateral damage. The troops needed to reach higher ground to stave off yellow fever, and General Santa Anna was on his way.2

Santa Anna had been kept busy by affairs in the capital. After marching back from Buena Vista, he quelled a rebellion in Mexico City, reestablished order, and promised the people of Mexico that he would defeat the invaders. Three days after news of the fall of Veracruz reached Mexico City, he was marching toward the coast with an army of twelve thousand. He established headquarters near his summer estate and prepared to crush the Americans at a mountain pass called Cerro Gordo on the road to the capital.

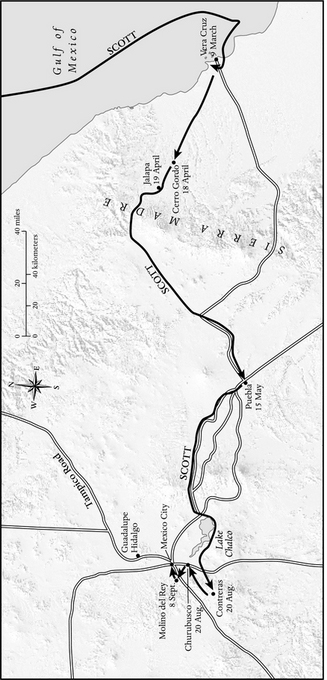

SCOTT’S ADVANCE TO MEXICO CITY (photo credit m10.1)

When Scott’s troops arrived at Cerro Gordo they found an impenetrable Mexican defensive line spanning two miles from the bank of a river across the pass and over two hills. “The hights of Cero Gordo looked almost as imposable to take as the hights of Gibralter,” one soldier wrote home. Scott sent his engineers to search for a solution. Captain Robert E. Lee proved the hero of the day when he discovered a mountain path around Santa Anna’s position. On April 18, the two armies battled on the road, and a portion of U.S. troops secretly moved around the Mexican left flank. They emerged in the rear of the enemy, causing instant confusion. As the Mexican troops began to flee, Santa Anna found himself face-to-face with Edward Baker’s Fourth Illinois Volunteers. He barely escaped with his life and had to leave behind in his carriage $18,000 in gold, a lunch of roast chicken, and the artificial leg he wore after battling the French in the Pastry War nine years earlier. The men of Illinois turned over the gold, ate the chicken, and brought the leg back home with them.3

The battle lasted only a few hours. It was a decisive victory, and while no Buena Vista, it finally brought the volunteers some measure of the glory they craved. “The American heart is again made to swell and throb with the emotions of joy and national pride and exultation, over another and not less glorious achievement of our indomitable army,” the New Orleans Delta proclaimed. But it was a bloody battle. Writing in his journal that evening, a Pennsylvania volunteer reported seeing “no less than fifty dead Mexicans all on one pile … Some groaning. It was enough to move the strongest heart.… Although our enemy’s[,] yet as an American I could not help having that sympathy which all soldiers should have for one or other especially when wounded in defense of their country.”4 The following day Scott continued the push forward toward the capital. Mexico’s president issued an edict calling on the men of the region to form irregular units and drive the invaders back to Vera Cruz. A light corps of mounted lancers could, it was hoped, achieve what the army could not. Mexico embraced guerrilla warfare.5

“Capture of Gen. Santa Anna’s Private Carriage at Battle of Cerro Gordo, April 18, 1847.” Edward Baker’s Fourth Illinois Volunteers had the good luck to capture Santa Anna’s artificial leg during the battle. They brought the leg back to Illinois as a trophy of war, and it now resides at the Illinois State Military Museum. J. Jacob Oswandel, Notes of the Mexican War, 1846–47–48 (Philadelphia, 1885), 131. (photo credit 10.1)

Among the most tenacious soldiers fighting for Mexico were the U.S. deserters who made up the San Patricio (or St. Patrick’s) Battalion. Desertions had been a problem for the U.S. Army since Taylor first entered Texas, particularly among the 40 percent of the regular army who were recent immigrants. Raised in foreign cultures, many immigrants looked at America’s fantasy of Manifest Destiny with skepticism, if not outright hostility. One Prussian volunteer from Ohio, Otto Birkel, noted in his diary that “the Founding Fathers of the [American] Republic were right to … recommend the strongest neutrality in all world affairs to their grandsons; but these grandsons thought themselves wiser, and now there is talk of uniting the entire continent of North and South America into one enormous state.” While anyone who had traveled through Europe “can very well see the madness of these plans,” in the United States “the majority of the people … do not doubt the possibility of the undertaking, and are supported … by countless demagogues.”6

Furthermore, while a significant proportion of immigrant soldiers were Catholic, the officers, for the most part, were Protestant, and the army reflected the virulent anti-Catholicism of American society in the 1840s. Anti-Catholic riots were common events in northeastern cities in the 1830s and 1840s. Just two years before the start of the war, objections to the use of the Catholic King James Bible in public schools led to a major riot in Philadelphia and a national conversation about the place of Catholicism in America. There were plenty of soldiers who claimed “that the present war is favored by the Almighty, because it will be the means of eradicating Papacy, and extending the benefits of Protestantism.” Catholic immigrants found it difficult to abide by some of the army’s rules. Soldiers of all faiths were advised, or compelled, to attend the Protestant services offered by the army chaplain. They were often banned from attending Catholic mass. Not surprisingly, they had trouble justifying a war waged on fellow Catholics.7

Mexicans recognized their quandary. From the opening shots of the war, the nation encouraged desertions with promises of respect, public assistance, and eventual land grants. In June 1847, Juan Soto, governor of Veracruz, distributed a handbill, in both Spanish and English, that appealed to “Catholic Irish, Frenchmen, and German[s] of the invading army!” It stated, “The American nation makes a most unjust war to the Mexicans and has taken all of you as an instrument of their iniquity. You must not fight against a religious people, nor should you be seen in the ranks of those who proclaim slavery of mankind as a constitutive principle. The religious man … is not on the part of those who desire to be the lords of the world, robbing properties and territories which do not belong to them and shedding so much blood.” Deserters would not be alone; “many of your former companions fight now content in our ranks. After this war is over, the magnanimous and generous Mexican nation will duly appreciate the services rendered, and you shall remain with us, cultivating our fertile lands. Catholic Irish, French, and German!! Long live liberty!! Long live our holy Religion!!” Two months later, Santa Anna issued a similar circular promising land and equality to American soldiers.8

More than a few Catholics found appeals like these persuasive, and decided to switch their allegiance. Under the leadership of a tall, blue-eyed Irishman named John Reilly, who deserted from Taylor’s camp across the Rio Grande from Matamoros, 150 former U.S. soldiers became one of Santa Anna’s greatest weapons, experts at operating the artillery that the U.S. Army employed with crushing effectiveness. Fighting under a shamrock-festooned flag, with promises of land and glory as a reward for their service, the St. Patrick’s battalion knew that surrender to the United States was the equivalent of death. Although many members of the battalion were recent immigrants from Europe and not American citizens, the U.S. Army considered them all traitors.

The road north from Cerro Gordo passed through miles of jungle full of musical birds of all hues. A Pennsylvania volunteer declared it “the prettiest country that I have yet seen … like the Garden of Eden more than anything I can compare it to.” Scott spent the first half of May in Jalapa, a scenic town of gardens and orange groves. The troops delighted in the temperate climate four thousand feet above Veracruz. Everything is “neat and clean,” wrote a volunteer, “not only the streets and houses but also the citizens.” It reminded many volunteers of home, and inspired fantasies of Americanization. One volunteer found it “easy to imagine ourselves in some thriving Yankee town.” Another was “astonished as well as delighted to see such an intelligent set of people. I did not think that there was such people in all Mexico judging from those I had seen before. Business is done here in a neat and Yankee style. The females are beauty’s they cannot be beat.”9

But perhaps the similarity of Jalapa to the United States exacerbated their homesickness, for what most of the twelve-month volunteers imagined was being back in the United States. They were sick of Mexico. Carl von Grone, a Prussian serving with Scott, wrote to his brother in Germany that “the numerous thieving riff-raff” among the volunteers “committed the most shameless acts of depravity on a daily basis” in Jalapa, “including the robbing of women on open streets, thefts in their accommodations, break-ins, robbing of churches and so on.”10 Their enlistments were almost up, and despite Scott’s entreaties and the recent victory at Cerro Gordo, virtually none of them wanted to continue fighting. As Colonel Pierce M. Butler, commander of the South Carolina volunteers, wrote to the governor of his state, “The contest is unequal and the service an inglorious one. The universal voice of the Army, Navy, and Volunteers, is for terminating this contest, and peace would be to them the most welcome news.” Their terms of service over, the regiments left Mexico in droves, and American papers sought to justify their unwillingness to continue fighting.

The Milledgeville, Georgia, Recorder turned to John Hardin’s memory for help. It claimed that the “universal” desire of the soldiers to come home was shared by “the heroic Col. Hardin, in a letter received at Washington just previous to his lamented fall.” John Hardin had again become the unlikely spokesman for ending the war, having, in fact, written Senator Douglas just before his death asking for the chance to ship out to Veracruz, and stating that if he could not, he saw no point in continuing in the army.11

Scott’s troops had had their battle and were now ready to return home with what they considered to be honor. Their honor was derived from participating in a fight, not from conquering Mexico or seeing the march through to its end. Few were as lucky as Colonel Edward Baker’s Fourth Illinois, who returned to the United States not only with honor but with Santa Anna’s artificial leg as well.

This left Scott deep in Mexican territory with less than eight thousand soldiers, three thousand of whom were incapacitated by illness. In mid-May he moved on to Puebla, halfway between Veracruz and Mexico City. The second-largest city in Mexico, Puebla impressed the troops with its scenic mountain setting, cathedral, tremendous bullfighting stadium, and “fine large stores.” Scott’s remaining forces spent ten trying weeks in Puebla over the summer of 1847, waiting for the arrival of reinforcements. Morale was low and the soldiers were continually harassed by irregular troops. William Tobey, writing for the Philadelphia North American, reported that thirty soldiers had been murdered by guerrilla partisans, whom Americans called “rancheros,” since leaving Veracruz, “and they will hang on our skirts and continue to kill stragglers.” Six Illinois volunteers were killed in three days.12

To the men of the army, the fault for all of this was clear. Polk was not supporting the troops. Scott asked for more soldiers, and Polk hadn’t granted them. Tobey, writing explicitly from a “Loco Foco,” or northern Democratic perspective, condemned Polk and the “quack warriors at Washington” for the halt in operations. Polk failed to send reinforcements in a timely manner, despite Scott’s “warning advice,” because of political resentment against the Whig general. The Polk administration’s “power was fast crumbling and falling away, and though they could not arrest their own downfall,” Tobey explained, they “would not consent to see others rise above them.” As for the “ ‘right or wrong’ supporters of Mr. Polk,” the “brother democrats who have not yet discovered who James K. Polk is,” Tobey assured them that “I do not know a democrat in the whole army, regular or volunteer, who does not execrate the man and his war measures.”13

One of the “war measures” causing Scott particular irritation was Nicholas Trist. Trist arrived in Veracruz on May 6, well after Scott’s departure. He carried with him two pistols (one of which was quickly stolen), the treaty, and a burning ambition to bring the war to a close. He was almost immediately stricken with the diarrhea that was plaguing the troops, and when he caught up with the army in Jalapa he was too ill to meet with Scott in person. Instead, while high on the large quantities of morphine he was “obliged to take … to save [his] life,” Trist sent Scott a packet of papers. Included within them were an official letter asserting Trist’s authority to negotiate a treaty and a letter to the Mexican foreign minister, which Trist ordered the general to deliver to the Mexican authorities.14

This was a mistake. Scott knew full well that Polk was doing all in his power to find a Democratic general to replace him. Polk had proposed that Congress create the position of lieutenant general so that he could elevate Thomas Hart Benton to a position outranking both his Whig generals. Congress demurred, which left Scott in charge but furious. And before Trist’s arrival in Mexico, Scott had received “reliable information from Washington” about Trist’s “well-known prejudice against me.” This usurpation of military authority by a common clerk was too much for Scott to bear. Trist had the authority to negotiate a treaty, but surely not to issue commands to the commanding general. He refused to comply with what Trist insisted were the president’s orders. Outraged by Scott’s response, a drugged Trist began an imperious thirteen-page letter by candlelight that night in his tent. He bragged to his wife about the dressing-down he delivered to Scott: “If I have not demolished him, then I give up.”15

Scott was not demolished, but he was angry. He moved on to Puebla without so much as speaking to Trist. But he was not one to step back calmly from an insult. Trist’s letter was a “farrago of insolence, conceit, and arrogance,” hardly the words of a gentleman, and Scott would have nothing to do with the so-called diplomat. Trist wrote his wife that Scott was an “imbecile” of “bitter selfishness and egregious vanity.” And then he forwarded copies of his correspondence with Scott to the State Department. Scott, who was just as convinced as Trist that he was dealing with a particularly unreasonable individual, also wrote to Washington. Buchanan and Polk were astounded by the correspondence, particularly after Scott threatened to resign his post on account of “the total want of support and sympathy on the part of the war department.” Trist was the last straw, Scott wrote. He couldn’t be expected to conduct critical military operations with “such a flank battery planted against me” as this commissioner.16

Polk was tempted to accept Scott’s resignation, and had there been a remotely capable Democratic general waiting in the wings, he would have done so. “The truth is that I have been compelled from the beginning to conduct the war against Mexico through the agency of two Gen’ls highest in rank who have not only no sympathies with the Government, but are hostile to my administration.” All the good generals were Whigs, and Congress refused to do anything about it. He declined Scott’s resignation and watched as the feud escalated. Privately, Buchanan reassured Trist that the administration supported him. In July and August, reinforcements in the form of new recruits finally arrived in Puebla, and Scott was ready to move on to the capital.17

Santa Anna, in the meantime, had recovered from his humiliation at Cerro Gordo. In the face of taunts and harassment on the streets of Mexico City, he reasserted his powers as dictator over the Mexican Congress and began organizing a defense of the city. Announcing to the people that he would fight a “war without pity unto death,” he constructed fortifications around Mexico City and concentrated twenty-five thousand troops at three vulnerable points around the city.18

On August 7, the fourteen thousand men under Scott’s command began their final seventy-five-mile march to Mexico City. As they crested a mountain pass, they looked down on the Valley of Mexico. Many were overcome with emotion. Illinois colonel George Moore, a good friend of John Hardin’s, was one of the few twelve-month volunteers who reenlisted, despite his growing doubts about the war. He later wrote that the war “left a reproach upon” the United States “which ages upon ages will fail to remove.” But in 1847 the view from ten thousand feet amply repaid his decision to stay on as an aide-de-camp. “A full and unobstructed view of the peerless valley or basin of Mexico, with its lakes and plains, hills and mountains, burst upon our astonished sight, presenting a scene of matchless prospective that would bid defiance to the pencil of the most gifted landscape painter.” The troops then descended, intent on capturing a fortified city of two hundred thousand, surrounded by marshland, lakes, and a lava bed. And there was no retreat. The route back to Veracruz was riddled with murderous Mexican rancheros who wished them dead. The Duke of Wellington, watching events unfold from his lofty perch in England, declared that “Scott is lost—he cannot capture the city and he cannot fall back upon his base.”19

It was the final stage of the American military plan, and it proved to be the bloodiest fighting of the war. As at Cerro Gordo, Captain Robert E. Lee discovered a route around the concentrated Mexican forces. This one led directly through a lava badland more than three miles wide. The Battle of Contreras on August 19 was a hard-fought struggle between evenly matched forces over jagged lava rock. Santa Anna was on the verge of crushing the Americans but pulled back abruptly, as he had at Buena Vista, taking a portion of the best soldiers off to defend the gates of the city. He missed another opportunity for victory.

That evening a cold, heavy rain began to fall, and troops on both sides spent a miserable night on the field. On the morning of August 20, desperate U.S. troops, braving lightning and pouring rain, divided their forces. They attacked the remaining Mexican troops from two directions and routed the enemy in minutes of fighting.

Scott had opened up a road to Mexico City. They marched into Churubusco, a small village of whitewashed adobe houses with red tile roofs and colorful bougainvillea vines. There they met Santa Anna. The Mexican troops, with the San Patricio battalion manning the artillery, fought valiantly on the muddy ground at the monastery convent of San Mateo. The San Patricios repeatedly tore flags of surrender out of the hands of their Mexican comrades, knowing that surrender meant death for their treason, but by the end of the afternoon Scott’s forces had prevailed. The U.S. Army was now only three miles from Mexico City. Santa Anna had lost a third of his troops over the previous few days. The U.S. Army sustained a thousand casualties.

Seventy-two of the San Patricios captured by the U.S. Army were tried in two courts-martial. Seventy were initially sentenced to death by hanging, but Scott pardoned five and reduced the sentences of fifteen to jail, fifty lashes, and branding of the letter D for deserter. John Reilly, who had deserted before the war began, was one of the sixteen who were whipped and branded. Sixteen of the captured men were hanged soon after trial, a spectacle that both Mexicans and Americans found “revolting.” The remaining thirty awaited execution.20

The last stand of Santa Anna’s forces was at a line of interior defenses. Both armies were battered, and Scott’s troops were in no position to continue fighting. On August 24, Scott and Santa Anna agreed to an armistice for the purposes of opening negotiations. When an American wagon train entered Mexico City under the flag of truce in order to pick up supplies, it was attacked by the populace. Santa Anna did nothing to quell the riot. On September 6, the Mexican government formally terminated the armistice, and Santa Anna issued a proclamation to the residents of the capital that he would “preserve your altars from infamous violation, and your daughters and your wives from the extremity of insult.”21

Scott still had to capture two fortified positions, a mass of stone buildings called Molino del Rey, and the imposing Chapultepec Castle half a mile to the east. General Worth attacked the Molino at dawn on September 8 in a frontal assault with his whole division. Worth’s hope that the mill was deserted proved to be mistaken, and Mexican artillery rained down on the Americans. It was the bloodiest battle of the war, as the infantry struggled and failed to storm the buildings and a sharp clash between rival cavalry decimated both sides. One column of Scott’s forces lost eleven of its fourteen officers, and reports circulated among the men that Mexican soldiers had slit the throats of wounded Americans. U.S. troops continued the assault, however, and eventually battered down a gate leading into the buildings. They continued fighting, room to room, until their opponent eventually withdrew. The Mexicans suffered two thousand casualties, and seven hundred Americans fell.22

Four days later, Scott’s artillery began to bombard Chapultepec Castle. He had seven thousand remaining troops. The castle once had been the residence of Spanish royalty but was currently occupied by a Mexican military school. The following morning, September 13, the guns began firing at dawn, for two hours. Then the Americans began to scale the castle walls. They found that six of the military cadets, all teenagers, refused to fall back even after the Mexican army retreated. According to legend, one of them wrapped himself in the Mexican flag and jumped to his death in order to prevent the flag’s capture. In the aftermath of the defeat, los niños héroes were venerated by the people of Mexico.

The Battle of Chapultepec produced lasting heroes for Mexico but a crucial victory for the United States. As the victorious U.S. forces raised the American flag over the castle, the thirty remaining San Patricios were publicly executed in a mass hanging, despite pleas for clemency by priests, politicians, and “respectable ladies” of Mexico City. It left a “terrible impression” on the people of Mexico.23

Scott pushed forward to the walls of Mexico City, and after a loss of another nine hundred men, he took control of one of the city gates. Santa Anna found it impossible to hold the city, and fled with his army toward the northern suburb of Guadalupe Hidalgo. A delegation from Mexico City approached Scott’s headquarters under a flag of truce and surrendered the city. At 7:00 a.m. on September 14, the American flag was raised in the capital, and General Scott, in his most elaborate uniform, rode proudly into the city to the cheers of his men and the terror of the civilian residents. According to twenty-nine-year-old Mexico City poet and journalist Guillermo Prieto, “demons, with flaming hair” and “swollen faces, noses like embers” roamed through the city, desecrating churches and turning houses “upside down.”24

Military operations should have been over that day. Scott had conquered the Mexican capital after a dramatic series of military victories. But neither the people nor the government of Mexico were willing to negotiate. The army had no one to blame but itself for the Mexicans’ intransigence. Despite the best intentions of most of the officers, when it came to “conquering a peace,” U.S. troops were their own worst enemies. Northeastern Mexico was marked by “devastation, ruin, conflagration, death, and other depredations” committed by Taylor’s men against the region’s “inoffensive inhabitants.” One Mexican general wrote Taylor directly in May 1847 to learn if the U.S. Army intended to follow the laws of nations and fight in a civilized manner or continue to engage in warfare “as it is waged by savage tribes between each other.”25 Decades of Indian Wars had left their mark on U.S. combat.

“General Scott Entering Mexico City, 1851.” Carl Nebel captures the tension of General Scott’s entrance into Mexico City’s grand plaza on September 14, 1847. Dragoons cluster around Scott, protecting him from harm, while cannons face the square, ready to fend off attackers. A stone-throwing Mexican in the lower left and armed men on the roof make clear that the United States may have captured the capital but has hardly won the hearts and minds of its inhabitants. George Wilkins Kendall and Carl Nebel, The War Between the United States and Mexico Illustrated, Embracing Pictorial Drawings of All the Principal Conflicts (New York: D. Appleton, 1851), plate 12. (photo credit 10.2)

With a stubborn enemy refusing to surrender, Scott’s troops settled into a lengthy occupation. Volunteers, drunk on stolen liquor, committed rape and murdered unarmed civilians, and soldiers were in turn murdered on a daily basis. The two countries seemed no closer to a peace treaty than when Taylor had first crossed the Rio Grande. Bands of guerrilla rancheros formed and launched merciless attacks on Scott’s men. At least twenty-five express riders, attempting to get news from central Mexico to Veracruz, were captured and killed, wounded, or tortured by Mexican guerrillas.26 The war that was going to be over as soon as it began now seemed endless.

Yet suddenly, after two months of squabbling, Trist and Scott were on good terms with each other. After some initial attempts at negotiating without Scott’s help, Trist realized that he needed the general on his side. Scott, also anxious for peace, reached a similar conclusion. Nicholas Trist was the only man in Mexico who could officially negotiate a treaty. When Trist again fell ill, Scott sent him a get-well note, a jar of guava jelly, and an invitation to move to his own much more comfortable lodgings for the period of his recovery. All three were gratefully accepted.

The two men discovered that they had more in common than they ever would have imagined, not the least of which was a belief that the war should be brought to a conclusion as quickly as possible. Each man wrote to Washington in order to take back the nasty things he had said about the other. Scott called Trist “able, discreet, courteous, and amiable,” and asked that “all I have heretofore written … about Mr. Trist, should be suppressed.” He regretted the “pronounced misunderstanding” and assured the administration that since the end of June his communication with the diplomat had been “frequent and cordial.” Scott attributed the “offensive character” of Trist’s earlier letters to the effects of morphine. Trist also asked that his insulting letters about Scott be stricken from memory; “justice” demanded that his previous letters be withdrawn from public view.27

Perhaps not surprisingly, given this chain of events, Secretary of War William Marcy had a nervous breakdown. In late August, he retreated from Washington for a monthlong recovery. In the meantime, the rapprochement between the general and diplomat became a friendship as the two men happily spent hours discussing literature, politics, and, above all else, the prospects for peace in Mexico. Trist had discovered Scott to be “affectionate, generous, forgiving and a lover of justice,” he happily wrote his wife. This development was more disturbing to Polk than their previous argument. Scott, it was clear, could not be trusted. A friendship between him and Trist could only lead to trouble.28

So while there was ample reason for celebration, and plenty of ecstatic commemoration after the fall of Mexico City, for the most part matters were not going much better for James K. Polk than for the soldiers stationed in Mexico. The threat of guerrilla attack was one that Polk could fully identify with. His Democratic coalition had shattered over the Wilmot Proviso, and Democrats had lost control of the House of Representatives. Whigs would control the House when the Thirtieth Congress was seated in early December. The “growing unpopularity of the war” was news in London. Voices of protest against the war increased as the occupation dragged on through the fall, while at the same time a growing minority of Democratic expansionists began pushing for the annexation of the whole of Mexico as spoils of war. At a mass meeting in New York in support of annexing the entirety of Mexico, Sam Houston, the former president of the Republic of Texas, proclaimed the full “continent” a “birth-right” of the United States. “Assuredly as to-morrow’s sun will rise and pursue its bright course along the firmament of heaven, so certain it appears to my mind, must the Anglo Saxon race pervade … throughout the whole rich empire of this great hemisphere.” He was met with “great cheers” and cries of “annex it all” from the audience. The New York Herald assured readers that once annexed, Mexico, “like the Sabine virgins,” “will soon learn to love her ravisher.”29

Polk was sympathetic to Houston’s vision, but the All-Mexico Movement, as it was known, did nothing to improve the prospects of peace. And peace, above all else, was what Polk dreamed about—on the rare occasions when he slept, that is. The vitriol and controversy combined with his ceaseless labor took an increasing toll on his fragile health. Night after night Sarah pleaded with him to stop work and come to bed, while members of his inner circle noted his “shortened and enfeebled step, and the air of languor and exhaustion which sat upon him.”30 Yet Polk kept going. What he needed was peace with honor, and as much of Mexico as he could take with it.