CHAPTER

004

Shotguns & Arsenic

In a box in the Academy of Natural Sciences Library archives sits a well-used knife owned by Jim Bond. The slim pocketknife, made in central New York State, is a deluxe Premium Stockman Knife #69 made by Camillus Cutlery. The 4-inch knife sports imitation-bone handles and three retractable blades, including a time-worn spey blade inscribed “FOR FLESH ONLY.”

Through the centuries, ornithologists have killed birds in order to study them, and until recently the basic tools of the trade hadn’t changed much since the 1800s: a double-barreled shotgun to kill the bird, scalpel or scissors or knife to skin it, and arsenic to preserve it.

Here’s how Bond worked in the field, as his wife, Mary, described in Far Afield in the Caribbean:

“Jim collected in the morning and skinned in the afternoon. He had to work hard to keep up with what he collected, and the icebox took a fiendish delight in thwarting him. There was no shelf and everything had to be laid directly on the ice. When a bottom chunk melted the whole mass shifted, tobogganing the birds, cheese, eggs, and bacon to new positions, some out of reach. This always seemed to happen when we weren’t around, except in the middle of the night. Then the most awful crashing noise would make one of us leap out of bed.”

Mary wrote that she got upset when arsenic, sawdust, forceps, scissors—and blood, guts, and feathers—were on the kitchen table where they sometimes ate their meals, adding, “The job can’t be hurried and the excitement comes when after the skin has been cleaned and dusted with arsenic it is turned inside out. The feather side is pulled over the knobby bone structure of the head like a pullover sweater. Sawdust or cornmeal keep the fingers dry while working and I was astonished at how much manhandling the feathers could stand. When finished the skin is laid on its back with demurely crossed feet, cotton eyes, and folded wings, tagged with its Latin name, the date and place where taken, and the name of the collector.”

Bond’s pocketknife had a spey blade inscribed “FOR FLESH ONLY.” From the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University archives, ANSP.2011.019; photo by author

For her readers who found the account a tad gruesome, there was also this: “I stared down at the skins and each one seemed to acquire before my eyes a new personality, different of course from the brilliant creature of air, speed, and song when alive, but of deeper significance after being scientifically classified. Each had achieved a definite sense of enviable immortality.”

Humans have been offering birds that “sense of inevitable” immortality ever since the ancient Egyptians mummified falcons, but it wasn’t until the sixteenth century that the practice became widespread. That’s when French naturalist Pierre Belon devised a recipe for preserving birds—by disemboweling the bird, filling the cavity with salt, and then hanging it to dry before stuffing it with anything from tobacco to peppers. Alas, these bird skins still developed rot and insect damage.

The oldest stuffed bird still in existence is likely an African grey parrot that resides in London’s Westminster Abbey. The pet of Frances Teresa Stuart (1647–1702), duchess of Richmond and Lennox, the taxidermied parrot is displayed on a stand next to a wax effigy of the duchess. X-rays have shown that the entire skeleton of the bird, including its skull, remains intact. It is thought to have survived so long because it has been displayed under glass, protected from insects and humidity changes.

In the late 1730s, taxidermy got its first major boost when French pharmacist and naturalist Jean-Baptiste Bécoeur experimented with a wide range of chemicals to determine which were the most effective against insects. He tested fifty chemicals, one on each of fifty specimens, to see if any would remain free of insect damage for four years. Only four of the specimens remained intact. He combined the chemicals—arsenic, camphor, potassium carbonate, and calcium hydroxide—with soap to create a concoction that would eventually be known as arsenic paste.

Carolina parakeet collected by John James Audubon, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, 1843. Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, Ornithology Department, #136786. Photo by author

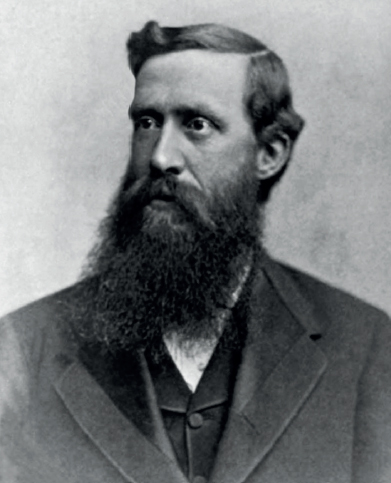

The use of arsenic as a preservative contributed to the demise of the Academy of Natural Sciences’ first main curator, John Cassin, who amassed the world’s largest collection of birds for the academy and spent two decades working with the study skins. These were the days before latex gloves and other safety precautions. Cassin died in 1869 at age fifty-five, with arsenic the suspected culprit.

Arsenic had also caused the early death of another noted ornithologist from Philadelphia, John Kirk Townsend, for whom the colorful Townsend’s warbler and the drab Townsend’s solitaire are named. Townsend died of arsenic poisoning in 1851 at age forty-one, after developing a formula that included arsenic as the “secret” ingredient for preparing taxidermy preparations.

Robert Ridgway, curator of birds at the US National Museum (now the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History), took a more straightforward approach to both shotguns and arsenic in his twenty-two-page 1891 treatise, Directions for Collecting Birds. He advised that the best gun for “all round” collecting is “a 12-gauge, double-barrel, breech-loading shotgun of approved make, with barrels 28 inches long, length of stock and ‘drop’ to suit the user,” and, in case someone wanted to shoot smaller birds, an auxiliary barrel for .32-caliber shells loaded with “wood powder, Grade D, and No. 12 shot.” This is the type of shotgun Bond often used in the field.

Ridgway also recommended mixing arsenic with alum to preserve birds, because “poisoning of fingers, through cuts or abrasion of the skin, is far less likely.”

Birding the Old-Fashioned Way

For folks in the late 1800s who preferred keeping bird skins in their drawers (so to speak) rather than putting feathers in their hats, a major resource was ornithologist Elliott Coues’s 1874 Field Ornithology. The subtitle said it all: “comprising a manual of instruction for procuring, preparing and preserving birds.”

The heavily bearded Coues (pronounced “Cows”), a US Army surgeon for nearly two decades, was a founder of the influential American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) and editor of its quarterly journal, The Auk.

The first sentence of Field Ornithology takes dead aim at its intended readership: “The double-barreled shotgun is your main reliance.” The fourteen-page first chapter is devoted entirely to shotgun use, with subjects ranging from selecting ammo to loading and caring for your gun.

With its gold-embossed owl logo on the cover, Coues’s treatise is chock-full of antiquated and cringeworthy nuggets on shooting warblers and “breaking the law unobtrusively.” Some highlights:

• On using a contraption called a cane gun, designed to look like a walking stick: “If you are shooting where the law forbids the destruction of small birds—a wise and good law that you may sometimes be inclined to defy—artfully careless handling of the deceitful implement may prevent arrest and fine.”

• On marksmanship: “It is finer shooting, I think, to drop a warbler skipping about a tree-top than to stop a quail at full speed.”

• On how many birds of the same species you should collect: “All you can get—with some reasonable limitations; say fifty or a hundred of any but the most abundant and widely diffused species.”

Elliott Coues’s classic guide to field ornithology advised, “Arsenic is a good friend of ours; besides preserving our birds, it keeps busybodies and meddlesome folks away from the scene of operations.” Public domain

• On arsenic: “Arsenic is a good friend of ours; besides preserving our birds, it keeps busybodies and meddlesome folks away from the scene of operations, by raising a wholesome suspicion of the taxidermist’s surroundings.”

In his book Biographical Memoir of Elliott Coues, Joel Asaph Allen, first president of the AOU, called Field Ornithology “without doubt, one of the most useful and popular manuals of ornithological field work ever put forth.”

A major proponent of the shotgun school of the late 1800s was ornithologist and collector Charles Barney Cory, a Boston Brahmin who wrote the first Birds of the West Indies (see next chapter). Cory, the son of a wealthy importer, developed his trigger finger early. At age eleven, he saved his money and secretly bought a pistol that he and a friend used to shoot at birds. Five years later, he began amassing a collection that eventually totaled 19,000 bird skins.

In 1902, at the height of his fame as an ornithologist, Cory was asked to speak at a meeting of the Audubon Society, which had been formed to protect birds from market gunning and the fad of using their feathers to adorn women’s hats. As recounted in Mark V. Barrow Jr.’s A Passion for Birds, Cory declined the invitation, saying: “I do not protect birds. I kill them.”

(In a similar vein, consider this anecdote from Warrior: The Legend of Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, by Peter Hathaway Capstick: The twentieth-century British ornithologist, spy, and pathological liar was once asked at a dinner party if he still shot and collected birds.

When Meinertzhagen acted like he hadn’t heard his fellow guest, she pretended to fire a gun and added: “You know—bang, bang!” To which he replied: “No, ma’am. Bang!”)

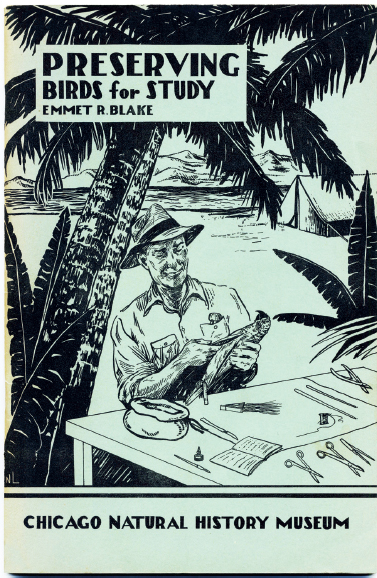

This field guide to skinning birds, written by former counterespionage agent Emmet Blake, suggested the use of powdered arsenic and other dangerous chemicals. Author’s collection

Thanks to the efforts of the Audubon societies and other fledgling groups, the public’s views on bird collecting grew more discerning, and the federal government intervened to stop illegal poaching and wanton slaughter. First came the Lacey Act, which prohibited so-called market hunters from selling poached game across state lines, followed by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which made it “unlawful to pursue, hunt, take, capture, kill, possess, sell, purchase, barter, import, export, or transport any migratory bird, or any part, nest, or egg or any such bird.” The act did allow the world’s major natural-history museums and several top universities to continue to expand their global research and build their collections under strict regulations. Bond’s work in the Caribbean was one small facet of this effort.

During WWII, the Smithsonian Institution even tried to recruit servicemen to collect specimens, producing a pocket-size softcover book called A Field Collector’s Manual in Natural History. Think of it as a citizen-science project for American soldiers and sailors. The introduction to the 1944 publication explains: “Many of the men serving in our armed forces who have been sent to all parts of the world have a keen interest in the animals, plants, rocks, and other objects about them, and, as their duties permit, find recreation in examining them.”

Inside the 138-page manual are instructions on mammals, birds (including eggs and skeletons), reptiles, amphibians, fishes, acorn worms, leeches—you name it. The largest section, twenty pages, is on birds. For a preservative, the manual suggested arsenic.

In 1949, Emmet Reid Blake (see chapter 008, “Twitchers & Spooks”) of the Chicago Natural History Museum wrote “Preserving Birds for Study,” a thirty-eight-page pamphlet with a similar aim: to instruct amateurs on how to “prepare themselves for the task of preserving birds collected for scientific purposes.” Blake’s list of instruments and materials alone would have deterred most birders. Suggested chemicals included heavy magnesium oxide, carbon tetrachloride, powdered arsenic, naphthalene flakes, and formalin or alcohol. Blake advises that carbon tetrachloride is the best solvent because it is “extremely safe to handle.” Carbon tet, as it was known, has since been banned except for limited industrial applications because of its potential damage to the human heart, blood vessels, liver, and nervous system.

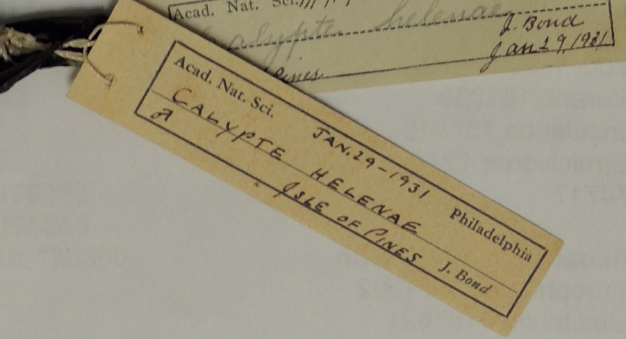

This label is attached to the bee hummingbird that Bond collected for the Academy of Natural Sciences on Cuba’s Isle of Pines in 1931. Photo by author

Although Bond was a major proponent of arsenic, he was not as quick to pull the trigger as many of his contemporaries. Mary Bond wrote in To James Bond with Love that the “accumulation of study skins was to Jim much less important than acquiring information on the distribution, behavior, song, and nidification [nesting] of the native avifauna of which so little was known. Although usually carrying a gun on his expeditions, he shot few birds.” Bond’s minimalist approach to collecting had an unforeseen downside, says Nate Rice, the Academy of Natural Sciences’ ornithology collection manager:

“To contrast what Bond did, other people were going to places, collecting specimens of several individual species every year, for decades. That’s the foundation for our understanding of environmental change, climate change, habitat manipulation, and population genetic changes. In the Caribbean, it would have been very valuable to have, say, one bird of whatever species collected every year on Cuba and Jamaica and the Lesser Antilles over the course of Bond’s career.”

Those seemingly excessive collections of birds by Charles Cory and others more than a century ago have a silver lining. “If it weren’t for guys like that, we wouldn’t know a lot of what we do about birds,” Rice says. “Those huge collections from the turn of the century and the early twentieth century are a gold mine to us researchers now for genetic studies, for environmental surveys.”

As an example of these old specimens’ value, Rice cites the study skins John James Audubon prepared for the academy, including specimens of such now-extinct birds as the Carolina parakeet. Researchers are able to sequence the DNA from a snippet of skin on the parakeet’s foot to get a genetic profile that lets them see how it relates to other groups of birds. From a snippet of feather they can also determine what its environment was like.

Equally important, Rice says, is that it’s impossible to know what techniques will be available to analyze the same study skins in ten or a hundred years. The bee hummingbird that Bond collected in Cuba in 1931—which now sits in a tray of hummingbirds in Cabinet 98 on the climate-controlled fourth floor of the Academy of Natural Sciences—may provide all sorts of new data in 2031 and beyond.

The Carriker Treachery

If every closet has at least one skeleton, then the largest one in Bond’s closet belonged to a lean, lifelong ornithologist named Melbourne Armstrong (Meb) Carriker Jr., whose career Bond sabotaged.

Carriker (CARE-ick-er), a colleague of Bond’s at ANSP from 1929 to 1938, was the most prolific collector of neotropical birds in history—more than 75,000 specimens. He was also a well-published authority on bird lice, collecting and studying thousands of specimens of these tiny, wingless insects.

Raised in Nebraska, Carriker became interested in birds early and was collecting and skinning them while still in high school. After graduation from the University of Nebraska in 1902, he joined a six-week expedition to Costa Rica, beginning a career in Latin America that spanned fifty years.

In 1927, Carriker and his wife and family moved to Toms River on the Jersey Shore so that their five bilingual children could attend American schools and Carriker might land a job at the academy in Philadelphia. After working as a carpenter for two years, he joined the academy staff as an assistant curator. Carriker was a newfangled ornithologist—one who wanted to be paid for his professional skills, in contrast to colleagues Rudy De Schauensee and Jim Bond, who had enough money to work for free and were thus more likely to keep their jobs when academy money was tight.

Then came the Great Depression. As Bond’s ANSP colleague Ruth Patrick told Bond biographer David Contosta, the academy back then “was dirty. It was run-down. Beggars used to come in and sleep on the windows.” Patrick said money was so tight that “lights were never left on at night. None. If you wanted to go through the building at night, you felt your way, or if you had a flashlight, that would be fine.”

When Carriker’s job was in jeopardy, bird curator Witmer Stone intervened, telling the academy’s executive director, Charles M. B. Cadwalader, that Carriker’s work in Peru was “one of the outstanding pieces of work that our institution has been able to carry out,” and that the birds Carriker had collected there represented the finest collection of Peruvian birds in the world.

During a 1934–35 expedition to Bolivia, Carriker sent back more than 2,250 bird specimens—likely more than Bond collected in his entire career. Carriker embarked on a second expedition to Bolivia in 1936. That’s when Bond apparently began to play institutional politics, and Carriker’s good standing took an abrupt turn. Bond’s Birds of the West Indies had just been published, and he and De Schauensee were embarking on a new project, Birds of Bolivia, which relied principally on the new species Carriker had discovered, as well as the quality and quantity of the bird skins he’d collected.

Rodolphe Meyer De Schauensee and Jim Bond examine a taxidermied unicorn bird collected by Meb Carriker. Courtesy of David Contosta

Once Carriker had left for Bolivia and was unable to defend himself, he received a letter from Cadwalader that began as follows:

“Yesterday I was much distressed and disturbed on hearing that some of the birds collected by you in South America were in really bad condition. I give below a list of 10 birds, some of which I have personally examined, and there is no question as to their being in exceedingly bad condition.” The reason: not enough arsenic.

“You must use arsenic in the preparation of your specimens and you must use sufficient arsenic to do the job right,” Cadwalader wrote. “Otherwise there is no use in continuing this work.”

Nate Rice, the academy’s ornithology collection manager, believes Bond was the provocateur behind Cadwalader’s letter to Carriker. He says the irony is that Carriker was chided for the poor quality of his bird skins, when it was Bond who was terrible at preparing specimens. And if Carriker stinted on the arsenic, he was ahead of his time.

“I think Bond was quite jealous of Meb Carriker. Carriker went all over Latin America for decades and was ‘the man’ in South America. Carriker submitted a proposal to the academy to start work in the Caribbean, and Bond was totally against it.”

If Bond was envious of Carriker, the situation no doubt worsened the following year with Carriker’s discovery of a bird that would be bestowed with one of the most enchanted names ever—the unicorn bird. Carriker collected at least four specimens of the turkey-like bird in Bolivia in 1937. Also known as a horned curassow or southern helmeted curassow, it weighed roughly 8 pounds, with wings up to 16 inches long.

Storrs Olson, curator emeritus of the Smithsonian, who in 2007 published the exchange of letters between Cadwalader and Carriker, noted: “No one else could have accomplished what he [Carriker] did, and his reward was getting kicked out of the academy so that Bond and De Schauensee could reap all the rewards.”

In October 1939, after the academy had dismissed Carriker, ostensibly for budgetary reasons, Bond and Rudy De Schauensee announced in an academy newsletter that the unicorn bird was a new species, Pauxi unicornis. Although the two ornithologists said that the new species had been discovered by Meb Carriker, that fact was lost in the newspaper coverage, as evidenced by this nonbylined wire story in the Escanaba Daily Press on October 10 of that year:

A turkey-like bird with a three-inch horn growing out of its forehead, which was discovered in the jungles of Bolivia, was announced by James Bond and Rodolphe Meyer De Schauensee, curators of birds of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. They call it the unicorn bird: Pauxi unicornis, to the scientist.

The bird resembles the new streamlined Thanksgiving bird which was recently developed by the department of agriculture, in its size, which is about eight to 10 pounds in weight. . . . The new species was discovered by a collector for the Academy.

Mr. De Schauensee, in announcing the finding of the unicorn bird, said, ‘The mystery surrounding this turkey-like bird is great, particularly in view of the fact that it is edible. Few edible birds escape the natives of a South American jungle. That it should have remained unknown in a relatively well-explored portion of the country is additionally strange.”

Despite the fact that Bond had never been to Bolivia, he and De Schauensee went on to write The Birds of Bolivia, published in two parts by the Academy of Natural Sciences during WWII.

Perhaps Mary was remembering this incident a quarter century later when she wrote (in How 007 Got His Name) about the day she and Bond visited Ian Fleming at Goldeneye. She observed, “Jim got out of the car, an inch or two taller than 007 perhaps but skinnier and capable of similar ruthlessness if the situation required.”

One final irony: The ANSP has a web page dedicated to Charles M. B. Cadwalader’s extensive accomplishments, including this feather in his cap: “The largest of the Cadwalader contributions to the Ornithology Department is the series of specimens collected by Meb Carriker in Bolivia from 1935 to 1938. Nearly 8,000 study skins are included in this spectacular series, all beautifully prepared by Carriker, one of the greatest field ornithologists of all time. Included in the collection are type specimens [the specimen that the scientific name of the bird species is almost always based on] for at least 74 new species of birds found during these expeditions.”

Photo by author