1

Concepts Underlying the Role of Private Equity Firms in Forming Alliances

In this chapter, we explain the notions and concepts that are required to understand our problem. We begin by introducing the concept of private equity (PE) in section 1.1. In section 1.2, we consider the concept of a strategic alliance, as used in this book. In section 1.3, we present French private equity firms (PEFs) more specifically and the formation of strategic alliances.

1.1. Private equity

Let us begin with an introduction to the main characteristics of PE (section 1.1.1), followed by a presentation of the features that are specific to the French market (section 1.1.2).

1.1.1. Main characteristics

PEFs are vehicles that enable individuals or institutions to operate in the PE market [PEN 07, p. 2]. These vehicles often invest large amounts in equity, typically in small-or medium-sized unlisted companies. They often occur in several stages and over several years [DES 01a, DES 01b, PEN 07].

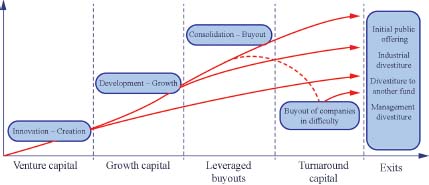

Depending on the lifecycle phase in which PEFs are involved in SME financing (Figure 1.1), one can distinguish between:

- – venture capital associated with the start-up of innovative companies with high potential;

- – growth capital and leveraged buy-outs (LBOs), which finance the transfer or acquisition of unlisted companies;

- – turnaround capital, which concerns firms that are experiencing temporary difficulties [BAN 07, p. 115];

- – more recently, intervention in companies wishing to unlist [GLA 08, p. 7].

Venture capital and turnaround capital operations are risky transactions and are characterized by an equity contribution. Growth capital and buy-out capital operations, which occur during the lifecycle of a company, involve a combined contribution of equity and debt (leverage effect) [BAN 07, p. 115]. LBO is defined as when a company is bought out by equity investors associated with the company’s management. The transaction is financed by equity capital as well as by a significant portion of debt that will have to be repaid in the years after the acquisition of the company. The source of repayments is cash flows that are generated either by the company’s operating cycle or through the sale of assets. Several LBO variants are possible.

Management buy-out (MBO) is the term used to describe a LBO transaction in which the management team that is already in place buys the company, with all or some of its employees and equity investors. When a company is acquired by an external management team and equity investors, the transaction is called a management buy-in. A combination of the last two variants is also possible and is known as BIMBO, a buy-in management buyout. An owner buy-out is defined as when a company is acquired by the owner-manager of that company in combination with equity investors. Finally, leveraged build-up is also possible. This is when an equity investor takes over several companies to form a larger entity from them. In general, these companies would be from the same sector. The build-up transaction is then referred to as “sector consolidation”. Buy-outs are also financed by a combination of equity and debt, usually with a very large debt component.

The above definition includes several particularities that characterize the field of PE. To highlight these, let us turn to Desbrières’ study [DES 01a, DES 01b].

Intervention in unlisted companies: The most distinctive feature is intervention in unlisted companies. First, these companies are not subject to the same disclosure requirements as listed companies. As a result, they tend to be less transparent.

In addition, information that is disclosed is generally not standardized or certified, making it more difficult to assess. There tends to be a more pronounced information asymmetry between these companies and their investors [NOO 99]. Second, as unlisted companies, their shareholding is often thinly spread. The liquidity of securities is therefore lower than that of listed companies. As a result, the PE market is inefficient and the transfer of securities takes place over the counter.

Figure 1.1. Private equity and business lifecycle (source: France Invest). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/burkhardt/equity.zip

Large amounts invested: The amounts invested by PEFs are often large, which limits the number of companies that can be financed and therefore the means of diversification.

Greater uncertainty regarding the profitability of investments: The profitability of investments undertaken by PEFs is more uncertain, in particular because of the nature of the activities of companies in which the PEFs intervene. They often operate in innovative sectors such as high technology. This uncertainty increases if PEFs intervene in companies that are in particularly vulnerable phases.

Information asymmetry, the lack of historic information (depending on the phase of the companies being financed), and uncertainty about future cash flows, all make standard valuation methods difficult to apply (such as NPV), which makes the valuation of companies to be financed more costly. In order to reduce the information asymmetry, the selection of projects to be financed is done through careful analysis because of diligence and the implementation of an often active and interventionist monitoring/control level in company management. As this is more in-depth and more expensive than with standardized and certified information, the number of files that can be examined by a PEF is limited. This inevitable focus on certain companies limits the diversification possibilities of the PEF portfolio. In return for such risk taking, PEFs generally hold significant control blocks and sit on the board of directors of the selected companies [SAH 90]. As a result, PEFs are able to constrain the discretionary space of managers and influence the nature of the strategy being pursued. This links the research question to the field of governance, which according to Charreaux [CHA 97] covers “all the mechanisms that have the effect of delimiting the powers and influencing the decisions of the top management, in other words, that ‘govern’ their conduct and define their discretionary space or freedom of action”. The contribution of PEFs is therefore not only financial but can also have a strategic nature [PEN 07, p. 6]. They are therefore active capital providers and thus contribute to the value creation process. Consequently, they seek to be involved in the distribution of the created value [DES 01b]. As a result, PEFs develop specific skills in the evaluation, selection and management of the companies they finance.

PEFs may remain on the board of directors after companies have entered capital markets. Their exit is made through the sale of shares to third parties or through the listing of companies financed on the stock exchange (initial public offering).

1.1.2. The French PE market

Let us begin by presenting the role of the French PE market in the global PE market (section 1.1.2.1). Then, let us examine (section 1.1.2.2) the different types of PEFs in France. In section 1.1.2.3, we will consider the main players on the French PE market.

1.1.2.1. The role of the French market in the global market

France’s share of the PE market puts it in second place in Europe. It is preceded by the United Kingdom [BAN 07, p. 116] and is followed by Germany (latest figures, source: France Invest). Looking at the development of the French PE market from 2006 to 2011, we see a continuous increase in the number of companies supported by PE (from 1,376 companies to 1,694 companies in 2011). The amounts invested increased continuously from 2006 to 2008 (from 10,164 million euros in 2006 to 10,009 million euros in 2008). In 2009, PE was hit by the financial crisis and there was a sharp drop in the amounts invested (4,100 million euros in 2009). However, the market has been recovering rapidly since 2010. In 2011, the figures were close to those in 2006 (9,738 million euros in 2011).

In 2012, however, PE was struck by an economic slowdown. Thus, there was a decrease in the number of supported companies (from 1,694 supported companies in 2011 to 1,548 in 2012) and a fall in the amounts invested of nearly –38% compared to 2011 (from 9,738 million euros invested in 2011 to 6,072 million euros in 2012). This decrease in investment hit all sectors of PE. Venture capital (innovation capital in Table 1.1) was at its lowest at 443 million euros compared to 536 million euros in 2006. Growth capital also fell; however, it maintained a higher level of investment than in 2009 (1,946 million euros in 2012 compared to 1,798 million euros in 2009). Buy-out capital, which is predominant in Europe, reached an all-time low at 3,568 million euros invested in 2012 compared to 6,015 million euros in 2011 and 8,075 million euros in 2006. According to France Invest, this can be explained by fiscal uncertainties (France Invest, 2012 study on the activity of PE, p. 17).

Table 1.1. Key figures for French private equity activity 2006–2012

(source: France Invest)

Development of investments in France 2006–2012

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | Variation | Variation | AAGR* | |

| 2011–12 | 2008–12 | 2008–12 | ||||||||

| In millions of euros | 10,164 | 12,554 | 10,009 | 4,100 | 6,598 | 9,738 | 6,072 | -38% | -39% | -12% |

| Innovation capital | 536 | 677 | 758 | 587 | 605 | 597 | 443 | -26% | -42% | -13% |

| Growth capital | 1,057 | 1,310 | 1,653 | 1,798 | 2,310 | 2,940 | 1,946 | -34% | 18% | 4% |

| Leveraged buyout | 8,075 | 10,340 | 7,399 | 1,605 | 3,512 | 6,015 | 3,568 | -41% | -52% | -17% |

| < 100 M€ | 4,063 | 4,938 | 2,857 | 1,358 | 1,863 | 2,413 | 1,972 | -18% | -31% | -9% |

| ≥ 100 M€ | 4,012 | 5,402 | 4,542 | 247 | 1,649 | 3,602 | 1,598 | -56% | -65% | -23% |

| Turnaround capital | 95 | 84 | 99 | 84 | 90 | 118 | 115 | -3% | 16% | 4% |

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | Variation | Variation | AAGR* | |

| 2011–12 | 2008–12 | 2008–12 | ||||||||

| In number of companies | 1,376 | 1,558 | 1,595 | 1,469 | 1,685 | 1,694 | 1,548 | -9% | -3% | -1% |

| Innovation capital | 335 | 416 | 428 | 401 | 458 | 371 | 365 | -2% | -15% | -4% |

| Growth capital | 481 | 557 | 707 | 779 | 916 | 960 | 871 | -9% | 23% | 5% |

| Leveraged buyout | 362 | 462 | 388 | 231 | 264 | 292 | 292 | 0% | -25% | -7% |

| < 100 M€ | 350 | 438 | 373 | 229 | 257 | 275 | 280 | 2% | -25% | -7% |

| ≥ 100 M€ | 12 | 24 | 15 | 2 | 7 | 17 | 12 | -29% | -20% | -5% |

| Turnaround capital | 24 | 38 | 28 | 31 | 25 | 17 | 20 | 18% | -29% | -8% |

This general economic slowdown in PE was not an exception in France. Invest Europe published similar figures for the PE market as a whole in Europe. Compared to 2011, the total amounts invested in 2012 fell by almost –43% in general on the European PE market (in France, the drop was –38%).

Nevertheless, despite the general economic downturn in 2012, PE played a major role in restructuring the productive fabric of major developed economies. This was particularly true for the French economy. PE was reviving SME and innovation financing after the financial market crisis [GLA 08, pp. 10–11]. Table 1.1 summarizes the main data.

1.1.2.2. The different types of PEF

In this section, we present the different types of PEF in France. An initial classification consists of differentiating between the types of PEF according to the source of their funds. This is detailed in section 1.1.2.2.1. A second classification is based on their legal structures. In section 1.1.2.2.2, we look at the main French investment vehicles.

1.1.2.2.1. Types of PEF according to the source of funds

According to the France Invest classification, there are three main types of PEF on the French PE market:

- – independent PEFs;

- – captive and semicaptive PEFs;

- – public PEFs.

These types of PEF differ according to the source of their funds. Thus, independent PEFs are PEFs for which the funds come from multiple investors, none of which hold the majority of the capital. In France, for example, this is the case for Auriga Partners, Siparex Groupe, Demeter Partners, Industries et Finances Partenaires, LBO France, and Unigrains. PEFs are said to be captive if they constitute a subsidiary of either a group or a company (French examples of this type of PEF are FTTI in France Télécom, TCV in Thalès, SEV in Schneider Electric, and Side in Michelin) [BEN 02], or of a bank or other financial institution (for example Unexo, a subsidiary of Crédit Agricole de l’Ouest’s nine regional banks, and Xange PE, a subsidiary of Banque Postale). A PEF is said to be semicaptive when there is a majority contributor of funds (for example ALV from Air Liquide, Innovacom from France Télécom, Aster from Schneider Electric) [ZOR 10]. For public PEFs, all or a large part of the funds come from public bodies (for example CDC-Entreprises, Oséo, FSI).

Hirsch and Walz [HIR 06] distinguished between independent, affiliated and public PEFs.

Independent persons can also be directly involved in the financing of high potential innovative SMEs. They are called business angels. They are often former business leaders, senior executives and/or young retirees or family members who come together to invest in a common project.

1.1.2.2.2. The main investment vehicles

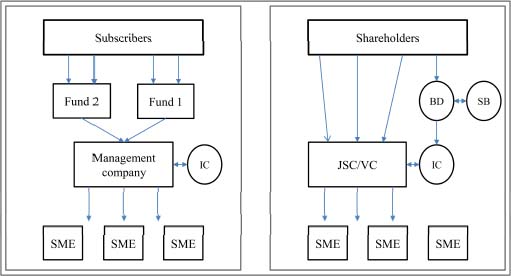

In France, PEFs mainly take the shape of venture capitalists (VCs) or investment funds (venture capital mutual funds [VCMF1]). Figure 1.2 illustrates these two investment vehicles : to the left of the image is an investment fund and to the right is a VC.

Figure 1.2. Legal structure of VCMFs (left) versus JSC/VC (right)

The VC structure was created by the French State in 1984 and is the oldest structure of French PE [GLA 08, p. 23]. It is a joint-stock corporation (JSC), which can take the legal structure of a public limited company (PLC), a limited liability company or partnership limited by shares. The VC statute favors investment in PEs through tax advantages in return for investment of a certain quota in unlisted SMEs and a minimum holding period of 5 years.

Subsequently, VCMFs were created. They belong to the UCITS family (undertakings for collective investment in transferable securities). They also offer tax advantages that are subject to a certain quota being invested in unlisted companies and a certain holding period [AFI 05]. VCMFs are more flexible investment vehicles than VCs and allow a wider public to invest in PE. A VCMF consists of an investment fund, on the one hand, and a management company, on the other. The fund issues units that investors can subscribe to. Their liability is limited to their contribution of funds. The fund has no moral responsibility. The latter is taken on by the management company. In this structure, investors are passive capital providers. The management company manages the funds and makes the investment decisions.

Today, these VCMFs often take the form of innovation-focused mutual funds (FCPIs) or local investment funds (LIFs), respectively created in 1997 and 2003, which attract even more physical investors to PE by again offering certain tax advantages.

Aside from slight differences in taxes and development methods, as well as a shorter investment period in supported companies for VCMFs (generally limited to between 10 and 12 years for VCMFs and usually unlimited for VCs), the two types of investment vehicles entail a different allocation of decision-making rights, in particular when it comes to investments. For VCMFs, investment decisions can be made by the management company independent of the fund’s subscribers. VCMFs with an investment committee (IC) are an exception to the rule (PE in Figure 1.2) if the committee consists of the main fund subscribers. The independence of investment decisions that are undertaken by the management company may then be called into question. For VCs, shareholders can influence a company’s investment decisions through their seats on the board of directors or the supervisory board (respectively, BD and SB in Figure 1.2).

For this study, let us clarify certain terms. We use the term “private equity firm” or “PEF” to describe all investment vehicles, so both VC and VCMF. In addition, the term represents the full spectrum of PE, in other words it includes specialized investment vehicles from start-up to turnaround. When we use the term “VC”, we will specify whether we are referring to an investment vehicle that is specialized in venture capital or whether we are referring to the legal status of a PEF that has opted for the (legal) status of a VC.

1.1.2.3. The main actors

In this section, we discuss the presence of the State in French PE and the main PE companies in France. The French State indirectly plays a significant role in the financing possibilities of French SMEs and the organization of the French PE market. A major player in French PE is CDC-Entreprises, a management company subsidiary of Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations.

Created in 1816, the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations (in English, Deposits and Consignments Fund) serves the general interest and economic development of France. It is also known as the “financial sword arm of the State”, and it manages the pension funds of civil servants and all savings funds, such as the French livrets A, livrets bleus and Codevi. It ensures their security and liquidity, while investing these funds in the public interest. When it was created, the funds were invested in government bonds, but nowadays they are allocated, among other things, to financing business development (mainly SMEs and territories) and PE.

In 1994, the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations created the management company CDC-Entreprises, which is a subsidiary. CDC-Entreprises manages all funds that are intended for minority shares in SMEs. CDC-Entreprises in turn owns two subsidiaries: FSI Régions and Consolidation et Développement Gestion. CDC-Entreprises funds are jointly subscribed by the State, the European Investment Bank, the Caisse des Dépôts, banks, insurance companies and various private industrial funds (source: CDC-Entreprises website). CDC-Entreprises also owns a significant portion (over 25%) of Oséo, a PLC in which the State holds a majority share of over 60%. Oséo is therefore a public company. Its vocation is to contribute to making France a great country of innovation and entrepreneurs2. First and foremost, it facilitates access to financing where the market does not allow this in a satisfactory manner. This therefore mainly concerns innovative SMEs. Part of its mission is to guarantee bank financing and the intervention of own funding bodies, such as PEFs. This guarantee of Oséo’s access to bank and equity financing was increased after the financial crisis in 2008 and the implementation of a recovery plan by the French State in 2009. In this way, the State has endowed Oséo with two new exceptional funds to guarantee access to financing [OSÉ 10, p. 215].

In 2008, the commitment from CDC-Entreprises and private investors was taken over by the Fonds stratégique d’investissement (FSI) France Investissement. The managed funds were invested in over 190 national and regional PE vehicles (source: FSI website). From July 2013 onward, the Public Investment Bank, which was intended to finance the French economy, brought together CDC-Entreprises, the FSI, FSI Régions and Oséo. The first three became “BPI-Investissement” and Oséo became “BPI-Financement”. The Public Investment Bank (Banque Publique d’Investissement [BPI]) was created on an equal footing by the French State and the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations in order to strengthen the financial support provided to companies.

In 2012, France Invest’s annual study on the activity of PE in France indicated that the funds raised by PE mainly came from public entities and that the latter were on the rise. For its part, CDC-Entreprises reported that in 2012, one in two companies that were supported and financed by PE was, directly or indirectly, funded by CDC-Entreprises through the FSI.

At the national level, France Invest is the only French professional association that is specialized in PE, which has the mission of deontology, control and development of the practices of the profession in France3. It federates the entire PE profession in France and ensures it is promoted and developed. In 2012, it had nearly 270 active members and included all the PE structures set up in France. Finally, Unicer (Union nationale des investisseurs en capital pour les entreprises régionales) specifically brought together some of France’s regional capital investors.

Having stated the main concepts of PE and its French specificities, which are useful to understand our research problem, let us now discuss the concept of a strategic alliance.

1.2. The concept of a strategic alliance

Strategic alliances are the core topic of numerous studies, mainly in the literature on strategy [TEE 86, KOG 88, GOM 01, ING 03, JAO 06, HOF 07, LAV 07, WAN 07]. According to Barney [BAR 02] and Barney and Hersterley [BAR 06], a strategic alliance exists “whenever two or more independent organizations cooperate to develop, produce or sell products or services”. Gulati [GUL 95, pp. 620–621] agreed with the previous definition by characterizing an alliance as any voluntary form of interfirm cooperation, involving the exchange or joint development and including the contribution of partners in the form of specific capital, technology or assets.

In the French literature, more restrictively, some authors specify that alliances can only be between competing or potentially competing firms [ING 03, p. 4, KOE 04, MAY 07, p. 126] as opposed to partnerships that involve agreements between non-competing firms, in other words, firms in different sectors. Lehmann-Ortega et al. [LEH 13, p. 470], however, specified that this condition (whether companies are competitors or potential competitors) is “not necessary but is frequently seen”. The same authors pointed out that alliances are often formalized. They may give rise, for example, to cross-shareholdings, commercial agreements (which is often the case in client–supplier relationships), licensing agreements, the creation of a joint entity for the companies taking part in the alliance (referred to as joint ventures), or alliance contracts (contracts freely drawn up between the parties that define the terms of the alliance). Although it is less common in the literature, however, a strategic alliance does not exclude a non-formalized cooperation [LEW 90, HEL 92, ELM 01, p. 205], which is more common when the purpose of the alliance is to exchange organizational practices.

Our research question leads to a focus on specific strategic alliances, namely those for which the formation involves at least one company that is supported by PE. Therefore, these are typically alliances comprising at least one young SME that is not listed on the stock exchange, is active in an innovative or high-tech sector and is supported by PE. This raises a question on the specificities of this context. Young unlisted and innovative companies are usually characterized by [NOO 93]:

- – specific investments in human capital;

- – a lack of resources;

- – managerial omnipresence;

- – personalized relationships with the environment;

- – a network of companies that is comparable to that of the manager;

- – tacit knowledge and non-formal information;

- – uncertainty due to the innovative context and the precarious stage of development in which these companies find themselves.

Due to limited resources and high specialization, these companies usually build networks that allow them to source what they need externally. Cooperation in the form of alliances would therefore appear to be useful to them. The literature on alliances between SMEs declares that the formalization of alliances remains rare and non-formalized modes of communication are often preferred [JAO 06, p. 2]. Alliances are therefore more informal in nature and are often and primarily justified by a lack of internal resources [PUT 95, JAO 06, p. 5]. The condition of competition – or potential competition – between alliance partners, although often verified, does not seem to systematically occur in alliances between SMEs. Thus, Puthod [PUT 96, p. 1] defined an alliance between SMEs as “a means of sharing resources that is necessary for the development of the SME” without alluding to the condition of competition. Jaouen [JAO 06, p. 1] specified that an alliance differs from a simple intercompany cooperation because of its strategic nature. It therefore seems that, particularly for SMEs, competition is not a requirement for an interfirm cooperation to be qualified as a strategic alliance. In other words, the notion of strategic alliance is separable from the notion of “coopetition”.

Thus, closer to our topic of alliances between SMEs [PUT 96, JAO 06], if we refer to the definitions laid down by Gulati [GUL 95], Barney [BAR 02], Barney and Hersterley [BAR 06] as well as the French literature that is closer to our topic [JAO 06, PUT 96], we consider that within this study, an alliance is a cooperation agreement concluded between at least two independent companies, which has the objective of creating mutual benefit. It enables joint asset management and the pursuit of common objectives [YIN 08, p. 473] while allowing companies to maintain their autonomy outside the alliance relationship. An alliance is said to be strategic if it stands to gain competitive advantage and create long-term value [KOE 96]. Thus, in alliance relationships, companies combine their resources and knowledge base to achieve objectives that would have been beyond their reach had they gone it alone. The most cited objectives include:

- – access to additional resources;

- – the creation of synergies;

- – the achievement of economies of scale or of scope (for areas such as R&D);

- – knowledge transfer or learning, risk sharing;

- – conquering new markets (geographical or sectoral);

- – obtaining a critical size.

An alliance thus allows risks and costs to be shared, but also gains, in the case of a joint creation of new skills.

Common examples of strategic alliances are relationships between companies that enable the joint development of new products or services, or the development of customer–supplier relationships, international development, cost reduction and exchange of organizational practice, for example at the internal control system, the use of management tools, the way information is disclosed [STI 65, p. 149], methods of supply and delivery, production methods, etc.

Depending on the theoretical framework, a strategic alliance is defined in light of the specific properties of the theory. As a result, the content of our explanatory variable “PEFs” differs depending on the chosen theoretical framework [PEN 95, p. 10]. In our study, we refer to contractual theories, knowledge-based theories or sociological network theories. The former consists of the transaction cost theory and the positive agency theory. The transaction cost theory presents alliances as a hybrid mode of governance, placing itself between the hierarchy and the market and reducing transaction costs [WIL 91b, p. 271]. The agency theory emphasizes conflicts of interest and presents an alliance as a node of contracts that allow a balance of interests between contracting parties to be maintained at a given time [ALC 72, p. 779, JEN 76, pp. 310–311). Knowledge-based theories also encompass different theoretical frameworks and focus on key, inimitable resources and skills that provide a competitive advantage. An alliance is thus defined as a cooperation between companies that remain autonomous but pool their resources and skills in order to develop an activity, generate synergies or enable growth that would not have been possible without such cooperation (for example, [PER 01, p. 12; MEN 03, p. 4; HOF 07, p. 829]). The concept of social capital makes it possible to take into account the structure of the social environment in which companies find themselves. A company’s relationship with its partner(s) in an alliance then represents part of its social capital [HOF 07, p. 829]. On the one hand, this relationship constitutes an opportunity to give access to resources beyond the company’s borders [UZZ 96, p. 675] while simultaneously enabling it to attain a certain legitimacy vis-à-vis its external environment. On the other hand, it can also act as a brake on the development of the company [UZZ 97, p. 35; HOF 07, p. 830].

So what role can a PEF play in forming alliances? Is this a widespread phenomenon in the world of PE or does it only concern a minority of companies supported by PE? Before we look into answering these questions, it is worth noting that the specific context of PE in alliance formation allows us to distinguish between certain types of alliances.

First, we distinguish between intra- and extraportfolio alliances. Second, there is another differentiation between the types of alliances in PE, which is a priori specific to the French context: as we presented in section 1.1.2.2.2, there are two main legal forms of investment vehicle in the French PE domain, VCMFs and JSC/VCs. If the investment vehicle takes the form of a UCITS, investors holding the units are in principle independent of the management company, which makes the investment decisions. On the other hand, if the investment vehicle takes the form of a corporation, shareholders can influence decision-making. An alliance can thus be more easily formed between a company that collaborates with a PEF and a shareholder of the PEF. The alliance can then be described as “vertical” as opposed to “horizontal”, which is formed between companies that collaborate with the PEF (intraportfolio alliances) or with a company that is external to the PEF (extraportfolio alliances). In our empirical study, one PEF (Anonymous PEF) presents such alliance possibilities.

Finally, let us clarify a term used in this book. Given that we are looking at the role of a PEF in forming alliances for the companies it supports, we are particularly interested in the person within the PEF who is in close contact with the management of the supported companies. We expect this person to be the investment manager or the portfolio manager. In practice, it can also be an associate or a partner. As we discovered from our survey and the verbal feedback we received during telephone conversations with investment or equity managers, partners or associates, these terms are not used uniformly within the various PEFs. In this book, we use the terms “investment manager” and “portfolio manager” equally. These terms refer to any person within a PEF who directly supports the management of the portfolio companies. It may therefore be an associate or a partner.

1.3. Strategic alliance formation in French PEFs

In this section, we describe strategic alliance formation in French PEFs. First, we shed some light on the environment of alliance formation for companies supported by French PEFs (section 1.3.1). Then we present some preliminary descriptive data (section 1.3.2).

1.3.1. French PE: a favorable environment for the formation of alliances

French policies for strengthening the competitiveness of the French economy not only provide SMEs with access to finance but also increase interaction, develop joint projects and create synergies between various players. This requires creating an environment that is conducive to the formation of alliances. As already mentioned, one of these policies from 2004 involves launching Competitiveness Clusters. These clusters are part of the European cluster policy. Today, there are 73 in France. They are organized around a defined topic, a specific geographical territory and bring together various players: companies, research laboratories, universities, grandes écoles or other educational institutions, local authorities, financial institutions and PEFs. Oséo Innovation, the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations and the Agence nationale de la recherche are also among the participants. Private PEFs may also be involved. The aim is to create synergies from joint collaborations in order to set up strategic projects and partnerships between these actors. Collaborative strategic R&D projects done in this way can also benefit from public support4.

Apart from French government policies for strengthening partnerships between economic players in the field of innovation, French PEFs also favor the formation of alliances for their portfolio companies. Looking at the websites of French PEFs, an initial observation becomes clear: some French PEFs have set up networking clubs for supported company managers and other PEFs have made their networks of contacts available for the development of their portfolio companies. The aim of the networking clubs is, in particular, to develop commercial and industrial synergies between the portfolio companies. This includes, for example, the Siparex Club of the PEF Groupe Siparex (Siparex Group) or the Demeter Entrepreneurs Club of the PEF Demeter Partners. However, no information is available on examples of companies that have formed alliances in the presence of a French PEF, so one might be led to wonder: what is the real significance of the phenomenon?

In 2004, the statistical office of the European Union, Eurostat, prepared a preliminary study on business linkages (including alliances) in European companies (Eurostat: [SCH 06, NIE 04]. The survey was sent to all EU Member States, including France. However, it concerned all types of companies, not just those supported by PE. The data collected in France were not always complete. For France, it showed that companies formed strategic cooperations such as alliances for three main reasons: access to new markets, access to additional resources and cost reduction. If there were barriers to the formation of cooperations for French companies, it would essentially be the fear of loss of independence for managers of companies. The alliances formed mainly involved:

- – outsourcing;

- – creation of joint ventures;

- – other (nature not specified in the study);

- – networking.

The study also showed that in France, alliance formation of SMEs with fewer than 50 employees was only slightly less than that for companies with 50–250 or more employees. SMEs therefore seemed to be heavily involved in the formation of alliances.

However, the study did not provide any information on the formation of alliances by companies supported by PE. The databases also do not provide this type of information because the companies that form the alliances are usually unlisted. By their nature, they disclose little information and are rarely found in databases. Finally, if they are, it is nevertheless difficult to obtain information on their alliance-building practices. However, this does not mean that they do not form any. Indeed, as we will see in our own study, one explanation may be that the alliances formed often remain non-formalized. Studies on the formation of alliances in the presence of companies supported by PE therefore either have access to specialized databases (which do not exist for France) or they are limited to analyzing alliance formation for companies supported by PE for which the exit was done by initial public offering. Once a company is listed on the stock exchange, it must disclose a certain amount of information and is thus present in most databases. However, if we were to only study the phenomenon on companies supported by PE for which the exit was done by initial public offering, we would be very restricted and not very representative, because the exits by initial public offering represent no more than 5% of the exits in France. For these reasons, we decided to conduct our own survey. The first descriptive results are presented in section 1.3.2.

1.3.2. First descriptive data

Before attempting to explain the role of French PEFs in the formation of strategic alliances, let us first look at the extent of the phenomenon. In this section, we intend to present the first descriptive data from our survey, which makes it possible for us to quantify the formation of alliances. It is part of our multimethod study, which is presented in its entirety in Chapter 3.

1.3.2.1. Data collection

The survey was sent to France Invest members with the help of the Surveymonkey web application (surveymonkey.com). Non-French PEFs were excluded. When our survey was sent out in 2012, France Invest had 270 active members. The survey remained open for nearly eight months. The survey was designed to test our theoretical framework and is further explained in Chapter 3. We report here only the statistical elements that allow us, for the time being, to determine the extent of the phenomenon. The data collection was done by sending an email to all the investment managers mentioned on the websites of French PEFs that were members of France Invest. If there was no email address, we tried standard addresses such as surname.firstname@PEF.com, surname.firstname@PEF.fr, firstname.surname@PEF.com, firstnamesurname@PEF.com and initials@PEF.com/fr. This work was quite time consuming, and the response rate was minimal (about 10 responses). In parallel, the France Invest Statistics Center agreed to publish the link to our survey in two of its newsletters, which are systematically sent to France Invest’s PEF members.

Despite these efforts, the vast majority of responses were obtained by reminding each PEF by phone, one by one, often several times. This took over a month. The advantage of this process was that the vast majority of surveys were completed over the phone with our assistance. We were thus able to gain additional information on top of the answers provided by respondents. The answers we obtained should therefore fairly accurately reflect what the respondents wanted to express. In this section, we present our preliminary statistical results on the activity of forming alliances for portfolio companies of French PEFs that are members of France Invest.

- – In total, 83 PEFs responded to our survey. However, ultimately only 77 of the 83 completed surveys were deemed usable5. This represents a response rate of 28.51% (77/270). This rate is only approximate for two reasons. First, it can be assumed that not all PEFs involved in forming alliances for the companies they support wished to participate in the survey. This rate then underestimates the phenomenon. In addition, the actual response rate can be assumed to be higher if it is taken into account that the fund of funds6 may not be able to respond to the survey. Indeed, for an employee of a fund of funds, it can be difficult to know about forming alliances for companies supported by the various funds managed. Moreover, if we consider that not all French PEFs necessarily form alliances for their portfolio companies, this response rate can be seen as a first indicator of the minimal importance of the phenomenon. Second, we cannot rule out the possibility that several people within a same PEF may have responded to the survey. For the answers obtained after sending out the survey by email, it was not possible for us to verify this. However, the rate of return was very low (10 responses in total). As for the responses obtained from telephone calls, we were able to ensure that this potential duplication of responses was avoided, except when it was associated with the operating mode of the PEF. Thus, for the large PEFs that participated in the survey, several people within the same PEF responded to the survey when the PEF was generalist and therefore focused on different stages of development. In this particular case, investment managers could only respond to the survey for a specific stage of development which, by itself, was not representative for the PEF. There were no more than five cases where two people had responded to the survey. There may thus be an overrepresentation of one PEF compared to others, but this was accompanied by a more accurate representation of the activity of forming alliances of companies supported by PEF according to the stage of their development.

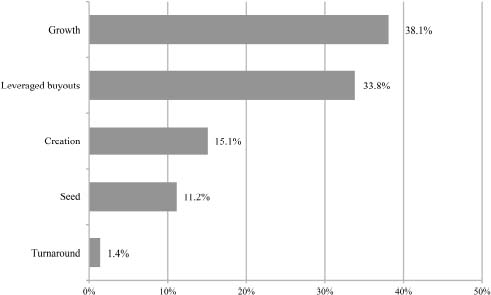

Of the 77 respondents, 67 provided us with their investment specialization. The breakdown is indicated in Figure 1.3.

These figures are only an approximation of the distribution of activity types in PEFs that responded to our survey, since this information was only obtained for 67 of the 77 PEFs that participated and provided a usable survey. The distribution of numbers between the different stages of financing is nevertheless comparable to that of the parent population (France Invest members)7 with regard to growth capital and buyout capital. In contrast, turnaround capital is underrepresented in our study and venture capital and seed capital are overrepresented. The underrepresentation of turnaround capital may be explained by the fact that the formation of alliances may be more significant when the companies being supported are at a more precarious stage of development. Conversely, alliance formation may be comparatively less important for companies in turnaround phase. An explanation can also be given for the overrepresentation of venture capital and seed capital (26.6% [= 11.5% + 15.1%] in our study compared to only 8.2% for the parent population). It is possible, for example, that PEFs that are specialized in supporting companies in the growth capital or turnaround capital phase may nevertheless support some participations in the venture capital or seed phase. In our survey, it is possible that these PEFs ticked the boxes “growth capital” or “turnaround capital” and “venture capital” or “seed capital”, whereas with France Invest, they are classified according to their specialization, growth capital or turnaround capital. Our numbers compared to those of the France Invest parent population, for the same activities, are presented in Table 1.2.

Figure 1.3. The specializations of PEFs participating in the survey according to the stage of development of supported companies

Table 1.2. Representation of PE activity types as a percentage of the survey compared to the parent population (France Invest)

| Respondents (%) | France Invest (%) | |

| Growth | 38.1 | 42.5 |

| Leveraged buy-out (LBO) | 33.8 | 39.7 |

| Seed, creation | 26.6 | 8.2 |

| Turnaround | 1.4 | 9.6 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

1.3.2.2. The significance of the phenomenon being studied

All the PEFs that responded to the survey were involved in the formation of alliances for the companies they support. What interests us, on the one hand, is to get an idea of the percentage of companies they support that have formed alliances and what types of alliances these are. On the other hand, we would also like to know to what extent PEFs have played one or more roles in the formation of these alliances and which ones.

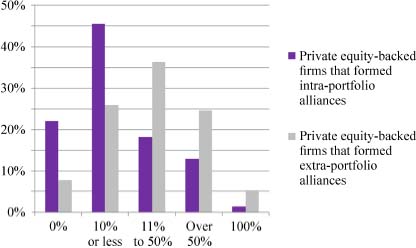

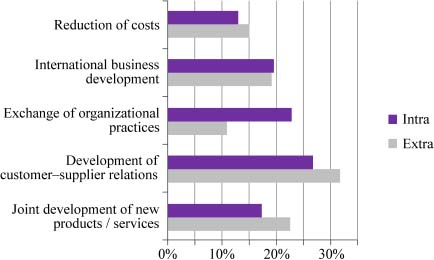

In the first question, we asked respondents to estimate the percentage of their supported businesses that have formed an intraportfolio alliance, as well as the percentage of supported businesses that have formed an extraportfolio alliance (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4. Percentage of companies supported by a French PEF that have formed an intra- or extraportfolio alliance. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/burkhardt/equity.zip

Seventy-seven PEFs answered the question. Of these, 60 (almost 78%) indicated that their portfolio companies had formed intraportfolio alliances and 71 (almost 92%) had formed extraportfolio alliances. First, we note that the percentage of companies that have formed an extraportfolio alliance is higher than that of companies that have formed intraportfolio alliances; 22% of respondents said that their participations did not form any intraportfolio alliances, whereas this was only 8% for extraportfolio alliances. We also note that for the PEFs that mentioned an intraportfolio alliance formation, in over 45% of cases this concerned 10% or less of supported companies. On the other hand, for the PEFs that indicated an extraportfolio alliance formation, over 35% highlighted that this activity concerned between 11% and 50% of supported companies, and nearly 25% of PEFs indicated that the formation of extraportfolio alliances concerned over 50% of the participating companies. In principle, the fact that extraportfolio alliances occurred more frequently, or concerned more companies than intraportfolio alliances, is not surprising, given that the possibilities for forming extraportfolio alliances are in principle unlimited, whereas intraportfolio alliances are limited to the investment portfolio of a PEF. However, these numbers say nothing about the possible roles played by PEFs in both types of alliances. Before trying to identify the involvement of PEFs, let us first look at the objectives of the alliances formed (Figure 1.5).

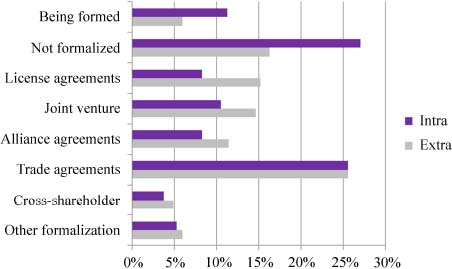

Figure 1.5. Objectives of intra- and extraportfolio alliances formed by companies supported by a French PEF. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/burkhardt/equity.zip

For PE-backed firms that have formed an intraportfolio alliance, over a quarter of these alliances involve customer–supplier relationships. This foremost objective is followed by the objectives of exchanges of organizational practices and international business development. As for the formation of extraportfolio alliances, the objective of alliances is most often to develop customer–supplier relations (in over a third of cases), followed by joint development of new products and services. In third position, again, is the international development of the company. While the objective of exchange of organizational practices would seem relatively important for forming intraportfolio alliances, it appears in the last position for extraportfolio alliances. Conversely, the joint development objective of new products/services seems less important in the formation of intraportfolio alliances compared to the formation of extraportfolio alliances. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that often, in the formation of intraportfolio alliances, for which the objective was to develop a customer–supplier relationship between the companies that take part in the alliance, the relationship begins with a phase of joint development. It is often necessary to adapt the product of one company to the needs of the other. However, the objective of the relationship remains a customer–supplier relationship that is supposed to be established between the companies. Concerning cost reduction, it often turns out not to be the main goal of the alliance but merely a secondary objective.

Let us now consider the degree of formalization these alliances take (Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6. Type of formalization of intra- or extraportfolio alliances formed by companies supported by a French PEF. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/burkhardt/equity.zip

In the formation of intraportfolio alliances, over a quarter of these remained not formalized. In the second place were alliances in the form of trade agreements. Together, these two types of alliances represented over half of all intraportfolio alliances. In the formation of extraportfolio alliances, over a quarter took the form of trade agreements. Next, all types of formalizations (joint venture, license agreement, alliance agreement, etc.) fell within 10–15% except for cross-shareholdings and the “other” category. Cross-shareholdings remained rather rare in both cases (formation of intra- and extraportfolio alliances).

The high percentage of alliances that were not formalized in the case of intraportfolio alliances is explained by the main objective of this type of alliance: the exchange of organizational practices, as shown Table 1.2. The presence of a common shareholder – the PEF – can also play a role in the fact that alliances remain non-formalized. One could think that the presence of the PEF induces trust between alliance partners sharing a same PEF. This will be further discussed throughout this book. The strong predominance of trade agreements in both types of alliances (intra and extra) seems to go hand in hand with the major objective of these alliances: the development of customer–supplier relations, as shown in Table 1.2.

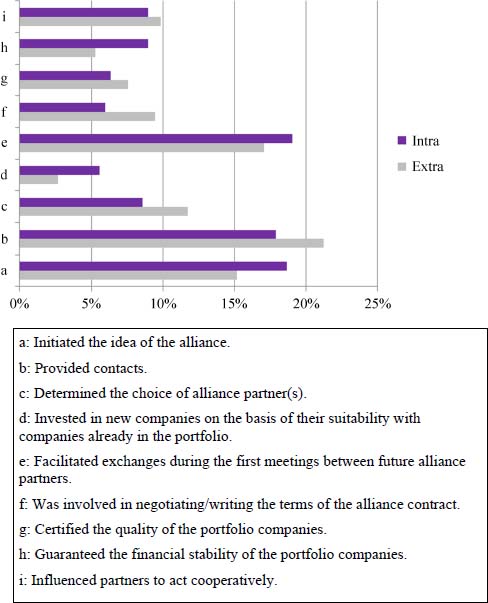

As mentioned before, the fact that companies supported by PE form alliances does not yet indicate that PEFs play any role. The objective of this book is to shed light on this. The survey already provides a first insight. Thus, the PEFs that participated in the study reported playing a role in forming both intra- and extraportfolio alliances (Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.7. Roles of French PEFs in forming intra- or extraportfolio alliances for the companies they support. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/burkhardt/equity.zip

On the whole, it seems that PEFs do declare that they play a role in forming alliances, whether these are intratype or extratype.

For the formation of alliances between supported companies (intraportfolio alliances), PEFs suggested that their roles included facilitating initial exchanges between alliance partners, initiating the idea of the alliance, and providing contacts. In the formation of extraportfolio alliances, so between at least one supported company and one non-supported company, the PEFs declare to have essentially brought the contacts, facilitated the first exchanges between future partners, and initiated of the idea of an alliance. We therefore see that the same three roles appear first, regardless of the type of alliance formed. The only thing that changes is the hierarchy of the three most significant roles. While in both types of alliances, PEFs reported bringing contacts, they reported to have determined the choice of alliance partner more often for an extraportfolio alliance than an intraportfolio alliance. The same applies to PEFs’ involvement in negotiating alliance contracts. The latter can be explained in part by referring to Figure 1.6, which shows that the percentage of non-formalized alliances is much higher when it comes to intraportfolio alliances. These alliances, which more often take the form of exchanges of organizational practices than for extraportfolio alliances, are not based on formalized contracts. Therefore, they do not require a PEF to intervene in the negotiation of the terms of the contract. On the other hand, in the formation of intraportfolio alliances, PEFs declared that they certified the stability of the supported companies more frequently than in the formation of extraportfolio alliances. In the formation of intraportfolio alliances, PEFs sometimes chose to invest in an SME on the basis of its compatibility with companies that were already in the portfolio.

Because of the feedback obtained during the data collection via this survey, it is important to specify that the use of terms such as “guarantee”, “certify” or “determine” (financial stability, company quality, choice of partners) does not mean that the PEF drafts guarantees or certificates or that it imposes a choice. Often, this is done indirectly. The mere presence of a PEF in the capital of companies can, indirectly, create trust with future partners in alliances, creating reassurance on the financial stability of supported companies. Similarly, when PEFs say that they “intervene” in the drafting of contracts, this does not mean that they intervene in the daily conduct of the firm. It is rather the fact that SME managers have the possibility of turning to the PEF in the event of communication difficulties and the PEF may be able to facilitate exchanges.

Having gained an initial idea of the extent of the phenomenon of alliance formation for companies supported by a French PEF and the roles that the latter can play in it, let us now consider an in-depth theoretical and empirical analysis of the problem in order to explain it.