3

Empirical Analysis with Explanatory Design of the Role of French Private Equity Firms in the Formation of Alliances

With the theoretical analysis complete, it now remains to test the propositions advanced in the Chapter 2 (see Table 2.7). In this chapter, we make explicit the methodology that we are using (section 3.1). It involves a multimethod study including an econometric study and a multiple case study. We then use it to test our theoretical model (section 3.2).

This empirical section seeks to test our theoretical framework on the French private equity market. It should allow us to respond to the general questions which we have raised. These are as follows:

- – Why do private equity firms intervene in the formation of alliances for their portfolio companies?

- – How do they intervene?

- – What is their impact on the resulting creation of value?

As these questions apply to the whole set of French private equity firms, the question of the general character of our propositions also arises.

Questions of how and why private equity firms intervene in the formation of alliances can be typically approached through case studies. The question of the general character of the possible roles played by private equity firms suggests a methodology which allows statistical generalization of the results, thus justifying the use of econometric techniques.

After justifying in a more detailed fashion the use of these two techniques (econometric and case study), they are, at first, presented separately. Later, their respective results are then reconciled in order to reach a conclusion at the level of the multimethod study as a whole.

3.1. Methodology: a multimethod study

After having presented the overall concept in section 3.1.1, we justify the joint and complementary use of statistical and econometric techniques and a case study in section 3.1.2.

3.1.1. The overall concept

The research question involves exploring the role of French private equity firms in the formation of strategic alliances and evaluating their impact on the resulting value creation. Thus, we must first of all answer the following general questions: what roles do private equity firms play in the formation of alliances, that is, how do they intervene and why? Bear in mind that we explicitly take into account the point of view of the small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) forming the alliance, as well as that of the private equity firm (PEF). Second, we examine the importance of the phenomenon. Is it a phenomenon generalizable among all French PEFs? The hypotheses resulting from the theoretical analysis of the issues posed in fact do have a general character and are valid for French PEFs as a whole. This general character must therefore also be put to the test.

Concerning the first point, the two questions of “how” and “why” can typically be treated through the use of a case study methodology [DAV 05, YIN 09, p. 175]. In contrast, the second point dealing with the importance of the phenomenon for the French private equity market requires the use of a methodology allowing us to analyze the possibility of statistically generalizing observed results over the whole of a parent population. This is what statistical and econometric techniques allow. Consequently, the empirical study is based on a confrontation between the facts and the theoretical concept, relying both on statistical and econometric studies and on a multiple case study. This empirical study will produce a summary of the results of the two studies that comprise it. It therefore consists of a multimethod study [YIN 09, p. 175], which aims to test the theoretical framework we have established.

The whole of the empirical study as well as the two methods comprising it are used, in our case, in an explanatory design, that is, with the explanatory, confirmatory objective of testing hypotheses [MIL 03, p. 83 and 84]. The statistical and econometric study and the case study are used in a complementary manner due to their specificities and according to their respective advantages and disadvantages. Although they are reported separately, their conceptualization and their implementation took place in parallel. Each of them therefore results in its distinct analysis and presentation, before we conclude the analysis with a final reconciliation of the results drawn from the different methods of empirical analysis [YIN 09, p. 174]. Before embarking on these analyses, let us begin by discussing the respective advantages of the two different methods to justify their use.

3.1.2. The joint and complementary use of statistical and economic techniques and case studies

We conjointly conduct statistical and economic studies and case studies because of their specificities and in order to use the two methods according to their respective advantages for testing our research hypotheses. The two methods are therefore utilized in a complementary manner. This section aims to detail the advantages of the two methods for answering our research question.

The strong point of statistical and econometric tests is that they allow us to detect correlations between variables and to understand the frequency of occurrence of the phenomena studied [YIN 09, p. 175]. They thus allow us to corroborate or to refute the propositions raised, allowing us to offer with a certain degree of certainty a statistical generalization of the facts based on a sample of data representative of the parent population of that sample [MIL 03, p. 83].

Used in an explanatory design, case studies, in turn, allow us to test the theoretical concept at a finer and more detailed level. Principally, they make it possible to respond to questions of “why” a certain phenomenon occurs and “how” it occurs. They thus complement the results of econometric tests as they can, once the correlations between variables have been detected, go beyond these correlations and verify the plausibility of the mechanisms underlying the links of causality, which we advance in theory to explain the facts [YIN 09, p. 175]. They thus make it possible to refine the degree of the analysis and to see if the hypotheses, of a general character, hold true in a specific context. They thus go beyond statistical abstraction and aggregated data. They enable a generalization of an analytical type. Moreover, in our specific case, they allow us to specifically account for the points of view of PEFs and SMEs in a single empirical result.

Contrary to the criticism often advanced that it is not possible to generalize from results obtained from case studies, we can plausibly claim to do so [SCA 90, p. 276; FLY 06, p. 219, p. 221; FLY 11, pp. 304–305]. However, we must recognize that the type of generalization differs in nature from that of econometric studies. Thus, we cannot claim a “statistical generalization” but rather a so-called analytical generalization, on the basis of plausibility tests [SCA 90, p. 270f.; GIB 08, p. 1468; GIB 10, p. 714]. With econometric generalizations, an inference is made about a population on the basis of data issuing from a representative sample of this population. In the case of an analytical generalization, we generalize the fact that empirical results support a previously established theory. The empirical results of the case studies are thus compared to a previously elaborated theory, which serves as a model or as a pattern for reproduction (a “template”). The result of the study may be considered to be particularly robust when several facts support the same theory (literal replication) while simultaneously not supporting a rival theory, which aims to explain the phenomenon (theoretical replication) [YIN 09, pp. 38–39 and p. 60]. We can thus claim with a certain degree of certainty to have found an analytical generalization.

By combining the two types of generalization (statistical and analytical), one can claim, in the end, a degree of generalization superior to that which one would obtain by using only a single method. Apart from allowing us to proceed to a more complex analysis using the two methods in a complementary manner, the multimethod study allows us to confirm the results by triangulation [YIN 03, p. 150, MIL 03, p. 83]. This is even more important when we need to grasp concepts which are difficult to evaluate and quantify.

3.2. Testing the theoretical framework

Testing the theoretical framework comprises three parts. The first two are devoted to the two components of the multimethod study: the statistical and econometric study (section 3.2.1) and the multiple case study (section 3.2.2). In section 3.2.3, we compare the results of the two analyses.

3.2.1. Econometric analysis

We begin by presenting the collection of data (section 3.2.1.1) before specifying the nature of the variables and the selected model (section 3.2.1.2). We then outline the approach allowing us to test our hypotheses through the selected model, the difficulties encountered in its implementation and the way in which we overcame them (section 3.2.1.3). Finally, we present and discuss the results obtained (section 3.2.1.4).

3.2.1.1. Collection of data

For the reasons cited in the introductory section, we were not able to access satisfactory secondary data (for example through access to databases) to carry out our study. We thus decided to carry out our own survey. The survey was designed by constructing two questionnaires:

- – one intended for French PEFs who were members of AFIC (Association Française des Investisseurs pour la Croissance, now known as France Invest);

- – the other intended for SMEs in which the PEFs held shareholdings.

The design of the survey in two questionnaires arises from our theoretical modeling. Systematically, we analyzed the problem from the respective points of view of SMEs forming alliances and the PEFs involved in these alliances. The questionnaires contained a first part intended to gather information allowing us to describe the phenomenon (number of alliances formed or percentage of companies in which the PEF had holdings having formed alliances; type of goals underlying these alliances; nature of contracts; roles that the PEFs see themselves as playing therein). This part was presented in the introduction. The second part of the questionnaire was designed to gather the information necessary to test our research hypotheses. The respondents were asked to indicate for different issues if they thought that the point mentioned had an impact on the formation of alliances, and if so, to what extent (ranging from totally negative to totally positive). A third part mentioned certain points related to the respondent or the SME/PEF for which they were responding.

The decision to ask the second section of questions as indicated above is based primarily on the fact that both the PEFs and the SMEs involved were somewhat reluctant to deliver information in the necessary direct form. This difficulty was confirmed after a discussion with the director of the statistical center at AFIC. The chosen solution allowed us to circumvent this and to obtain a relatively high response rate so as to be able to adequately perform our investigation. The responses thus obtained have a subjective character which is, however, balanced, at least in part, by the contrast between the points of view of the PEFs and the SMEs via the two questionnaires.

After design, a first version of the questionnaires was submitted, in a first phase, to the criticism of experts from FARGO (French Center for Research in Finance, Organizational Architecture and Corporate Governance) as well as CMBOR (Center for Management Buy-Out and Private Equity Research). This latter has already produced similar questionnaires in conjunction with EVCA (European Private Equity & Venture Capital Association, now known as Invest Europe). The questionnaires were then submitted for pretesting to the investment managers involved in the case studies and certain directors of their portfolio companies.

Once validated, the questionnaires were sent by email to the investment managers of the PEFs, which were members of AFIC, by means of the Surveymonkey website (http://fr.surveymonkey.com/). After many attempts, we were also able to contact Mr. Hervé Schricke, president of AFIC at the time of the survey. He gave us his consent for his association’s department of statistics to support these investigations by agreeing to publish links to the questionnaires, accompanied by an advertisement, in two of its newsletters. The questions were put online at the beginning of May 2012 for a period of 8 months. The investment managers of the PEFs were encouraged, on the one hand, to fill out the questionnaire intended for PEFs, and, on the other, to pass on the questionnaire intended for SMEs to directors of their portfolio companies. As described in more detail in the introductory part, the responses to the questionnaire addressed to PEFs were mainly obtained following telephone reminders. Attempts were also undertaken to meet the manager of the FSI (strategic fund for investment) so he could give us his consent to disseminate an e-mail including links to our questionnaires directly to PEF members. This request was not successful. The response from the questionnaire intended for SMEs was too low to be usable.

3.2.1.2. Specification of the model

We will start by presenting the dependent variable, as it is measured through the questionnaire, because it affects the choice of econometric model. We will then present the independent variables and the control variables. They have an impact on the way in which we will specify, and thus test, the chosen model. Finally, we will present the characteristics of the selected model.

3.2.1.2.1. Dependent variable

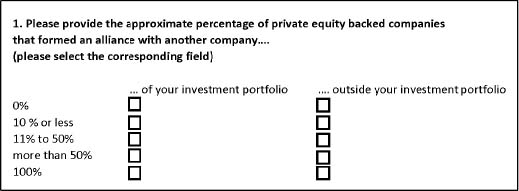

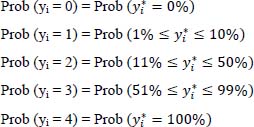

The dependent variable is the “formation of alliances”. In the questionnaires, one question was devoted to this. Respondents to the questionnaire addressed to PEFs were asked to indicate the approximate percentage of the companies they supported who had formed an alliance, either of intra- or extraportfolio type. They could choose from among five responses (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1. Overview of the first question of the questionnaire addressed to PEFs

Having posed the question in this way, the responses obtained for the dependent variable are shown in the form of intervals, answers of 0% or 100% being assimilated to intervals:

- Interval 1: [0–0%]; code as 0

- Interval 2: [1–10%]; code as 1

- Interval 3: [11–50%]; code as 2

- Interval 4: [51–99%]; code as 3

- Interval 5: [100–100%]; code as 4

The questionnaire as a whole was constructed so as to obtain responses for the formation of both “intra-” and “extra”-portfolio alliances. Based on this, we decided, for the econometric study, to perform two regressions, the first for the formation of “intraportfolio” alliances, the second for that of “extraportfolio” alliances. The dependent variables of the two models are referred to, respectively, as “allin” and “allex”.

3.2.1.2.2. Independent variables

Following our theoretical analysis, we distinguished three types of independent variables:

- – those arising from contractual hypotheses;

- – those based on a knowledge-based analysis;

- – those which simultaneously cover a contractual variant and a knowledge-based variant.

Here, we discuss only the designation of the independent variables as they appear in the regression, their meaning and the number of the hypothesis that they represent (for a summary of our hypotheses, see Table 2.7).

Contractual variables

- – The variable “Rp” represents the reputation of the PEFs (Hypothesis 1).

- – The variables “Ple” and “State” designate the presence of a competitiveness cluster or the State, respectively (Hypothesis 3).

- – The variable “maj” indicates a majority stake held by the PEF (Hypothesis 4).

- – The variable “Cot” indicates the publicly traded or otherwise status of the SMEs involved (Hypothesis 6).

Knowledge-based variables

- – The variables “Spsec” and “rgInt” designate, respectively, the sectoral specialization and the regional/international specialization of the PEF (Hypotheses 7a and 7b).

- – The variable “Diff” indicates whether the formation of alliances is for the PEF a way of differentiating itself on the private equity market (Hypothesis 9).

- – The variable “Ca” indicates the presence of the PEF on the board of directors of the companies they support (Hypothesis 11a).

Variables of mixed nature (contractual and knowledge-based)

The variable “Nbrepart” takes into account the number of shareholdings managed by the PEF (Hypotheses 8a and 8b).

Hypothesis 10, predicting a more prominent role for the PEF at the formation of “intra” than of “extra” alliances, might be tested by comparing the regressions on allin and allex.

Because of a lack of data, particularly due to the fact that the second questionnaire (intended for SMEs) could not be used, we could not use the econometric study to test Hypotheses 2, 5 or 11b, or parts of Hypotheses 8a and 8b. As for Hypotheses 7a and 7b, they could not be completely tested.

Although it was possible for us to test the impact of the reputation of a PEF on the formation of alliances (Hypothesis 1), we were not in a position to test Hypothesis 2, predicting that a PEF with weak reputational capital would have a greater tendency to insert its portfolio companies into alliances with partners with good reputations on the market.

Hypothesis 5 is associated with the impact of alliances previously formed by the SMEs supported by private equity on the formation of new alliances. The information necessary to test this hypothesis was included in the questionnaire intended for SMEs, which did not succeed.

Hypothesis 11b concerns the participation of the PEF in organizations such as AFIC, EVCA or others. The variable allowing us to take account of the participation or otherwise of PEFs in such associations is binary by nature: coded 1 if they are part of at least one association and 0 in the alternative case. The problem which finally led me to not retain this variable is that the questionnaire was only sent to PEFs who were members of AFIC. Thus, all the PEFs who replied received code 1 for this variable, which did not allow us to properly analyze the impact of participation/non-participation of PEFs in associations on the formation of alliances.

For Hypotheses 8a and 8b, we were not able to gather information concerning the geographical distance between the PEF and its portfolio companies and could not verify its impact on the formation of alliances.

For Hypotheses 7a and 7b, we predicted a positive impact of a regional or sectoral focus in a PEF’s investments on the formation of regional or sectoral alliances. We also predicted that a PEF’s investments in different countries would have a positive impact on the formation of alliances allowing international development of the companies involved. However, we only obtained information related to the general impact of the PEF’s investment focus on the formation of intra-/extra-alliances. Consequently, we could not measure the impact on the formation of certain types of alliance (regional/sectoral/international).

All these hypotheses were, however, tested by the case study method, which will be presented in its turn.

3.2.1.2.3. Control variables

The control variables are those variables which are likely to explain the formation of alliances (intra or extra) for companies supported by private equity, linked to determinants different from those associated with the independent variables. They allow us to ensure that our hypotheses are valid “all else being equal”. We selected four of these. They mainly consist of variables representing certain characteristics of PEFs or relating to the portfolio manager.

The first, “Spfin”, takes account of the PEF’s investment specialization according to the stage of financing (startup, venture, growth, turnaround, etc.). We may suppose that the more the PEF supports companies who are going through precarious phases, the more these companies will possibly lack resources and will thus be interested in forming alliances. In addition, the younger these companies, the more they will lack the visibility to attract alliance partners. The role of a PEF should thus be strengthened.

The variable “indus” indicates the membership of the PEF in an industrial group or company, and the variable “finan”, the membership of the PEF in a financial group (for example a bank). In these two cases, we are dealing with a captive PEF, for example a subsidiary of an industrial group or of a bank. We may thus suppose that a PEF, which is a subsidiary of a financial group, will adopt a financial rather than an industrial approach, which may have a negative impact on the formation of alliances. For PEFs, which are subsidiaries of an industrial group, we may suppose that the group or company investing in a start-up will be reluctant for the latter to form too many alliances, for reasons of self-interest. We may thus suppose that if the company invests in a start-up to support and subsequently profit from its know-how, the company may limit the formation of alliances for fear of losing exclusive access to this know-how [DUS 10].

Finally, the variable “Exp” takes into account the experience of the investment manager who supports those companies likely to form alliances. We may suppose that the more experienced this person, the more skills they will have to create relationships with the companies they support. Having had experience with a number of such cases, they will be likely to know more companies who may constitute potential alliance partners for the supported companies. The experience of the investment manager should thus have a positive impact on the formation of alliances.

By the same logic, we have included the variable “Nbresyn” representing the number of partners in syndication with the PEF. The fact that several PEFs co-invest in a single SME may have a positive effect on the formation of alliances by that company. A greater number of PEFs increase the skills and experience available, and thus the probability that the idea of forming an alliance will emerge. Moreover, the SME may also benefit from access to a larger network of potential alliance partners. We thus expect a positive link.

3.2.1.2.4. The nature of the independent and control variables

Except for the variable “Diff”, which is binary and thus takes the values (0; 1), all the other independent variables are of the type of responses to a Likert scale with six terms. The questions asked of the respondents relate to the impact of variables on the formation of either intra- or extraportfolio alliances. They could choose between six responses (not relevant; totally negative impact; rather negative; neutral; rather positive; totally positive). “Not relevant” indicates, for example, that if we ask a PEF if the fact of taking majority stakes has an impact on the formation of alliances for its holding, they could tick “not relevant” in the case that they do not take majority stakes. The “not relevant” information thus allows us to distinguish the PEFs who cannot answer the question from those who do not wish to respond to it.

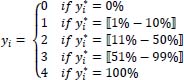

Measured thus, the independent and control variables are ordered variables. In other words, the categories of responses can be ordered in a hierarchy (except, in principle, for the “not relevant” response), although we cannot measure the distances between the categories [JAM 04, CAR 07, p. 111]. The variables are thus of an ordered, qualitative nature. They have been coded as follows:

- 0 = not relevant

- 1 = totally negative

- 2 = rather negative

- 3 = neutral

- 4 = rather positive

- 5 = totally positive

However, in coding these variables from 0 to 5 without further precision, we make these variables quantitative for the software, although they are qualitative and categorical. So as to better take account of their nature, we transform these variables (except for the variable “Diff”) into binary variables, taking the values (0; 1). For example, if the respondent indicates that the variable Rp has a “neutral” impact on the formation of alliances, the values for this variable will be as follows:

To do this, we indicate to the software that the variables are in binary modalities (dummy variables). In Stata, the software being used, this is done by using, for example, not the independent variable “Rp”, but the variable with the prefix “ib3.”, thus, “ib3.Rp”. The “i” (for “indicator”) indicates that it is to be treated as binary, the “b3” is an option that allows us to tell the software to base its calculations on the modality of the reference coded 3 (“neutral” in our case)1. Each modality of the variable (Rp in our example) is thus considered as binary.

This transformation, in turn, leads to eliminating the hierarchical nature of the variables. Excluding the “not relevant” category, a gradation does exist between the modalities, and we lose this information. However, as indicated above, if we treat the variables as discrete, the software uses a measurement scale of 0–5, which is also inaccurate. Moreover, in this case, we would have to exclude the category “not relevant” (coded 0) for the regression, as its inclusion in this continuous scale (ranging from 0 to 5) would be completely erroneous. We thus also lose this information, which, in our case, may be harmful given the small size of the overall sample and the sometimes non-negligible number of observations involving the category “not relevant”.

We continue by treating our variables as composed of several binary modalities. We thus lose the ranking information. Nevertheless, given that we are aware of the presence of a scale, we can “rectify” this loss of information when we interpret the results. The “loss” of information in the end therefore does not appear to be of great importance.

3.2.1.2.5. Models selected

With a dependent variable in the form of intervals, we have the possibility of using three econometric models:

- 1) regression by intervals intreg, which thus treats our dependent variable as a continuous variable, but one whose observations are only found within certain intervals;

- 2) probit/logit ordered regressions which treat our dependent variable as made up of several binary modalities, while keeping a scale between the categories;

- 3) linear regression by substituting for the intervals of our dependent variable the central values of each interval.

Let us return to point (1). Regression by intervals is a generalization of the tobit model. The function was designed, in particular, for data of the interval type. That is, data where we know the interval in which the observation is located without knowing its exact value2. This corresponds exactly to our dependent variable: respondents indicate a percentage interval of the number of its portfolio companies who have formed alliances, without yet indicating an exact number. They have a choice between five intervals. Through regression by intervals, our dependent variable (allin or allex) is thus treated as an a priori quantitative variable (going from 0% to 100%), but of which we only know the intervals and not the exact values. Each interval is thus conceived as a range of data with censoring to both left and right, called “interval censoring”.

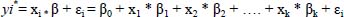

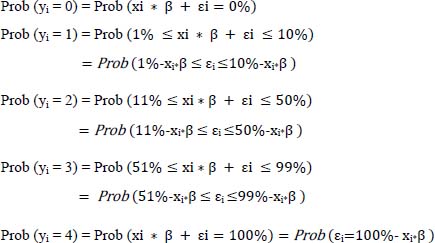

For point (2), a priori nothing prevents us using ordered logit or probit, which are the nonlinear models, considering in our case the dependent variable as made up of several binary categories with an order between them. These models are based on the introduction of a latent, unobservable variable y, which is assumed to be linear and which takes the values of our dependent variable which are observed each time that it crosses defined thresholds. As the latent variable is linear, we can reduce the problem to an analysis of the variance on this latent variable [LEB 00, pp. 10–11]. The two models (ordered probit and logit) thus take the following form [LON 01, pp. 138–139]:

where:

- –

= latent, unobserved variable, which represents the observed dependent variable of an ordered polytomous nature (yi);

= latent, unobserved variable, which represents the observed dependent variable of an ordered polytomous nature (yi); - – xi = the independent variables that, in our case, are qualitative and ordered;

- – i = the different observations or, in our case, the set of PEFs who are members of AFIC indicated by i and which allow us to observe the different values of yi;

- – εi = the error term.

In our case, the relationship between  and yi is specified as follows:

and yi is specified as follows:

The values taken by the independent variables thus determine that of the latent unobservable variable, which may be interpreted as a propensity to generate an event (of the type yi = 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4 in our case). We thus observe yi = 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4 when  finds itself in one of the intervals defined above. We deduce from this that (with “probability” = Prob):

finds itself in one of the intervals defined above. We deduce from this that (with “probability” = Prob):

We can then replace  by (xi * β + εi)

by (xi * β + εi)

The logit and probit regression models then differ as to the distribution function of the rule chosen for the error term εi. This is either a Gaussian rule (probit) with an expected value of 0 and a variance equal to 1, or a logistic rule (logit) with a variance of π2/3.

Concerning point (3), the third solution mentioned consists of dealing with our data through a linear regression on the central values of the intervals of our dependent variable. However, this would entail a quite coarse simplification of the nature of the data for our independent variable. Thus, we will continue by only using intreg and ordered logit/probit.

3.2.1.3. Implementation of the regression: difficulties encountered and their resolution

The application was conducted by means of the Stata software, version 12. Before proceeding with the regression, a look at the frequencies for the different categories of our dependent variables might prove useful in view of the problems associated with categories represented by low frequencies.

For allin as for allex, we notice that category 4, indicating that 100% of companies supported in the portfolio form alliances, is very sparsely populated (respectively, 1 and 4 observations). We therefore decided to combine it with category 33.

We also decided to not include the category coded as 0, which indicates that for the PEF in question, no company in its portfolio has formed an alliance of this type (intra or extra). This is interesting information at the descriptive level, as it signifies that some PEFs do not engage in these two types of alliance (intra/extra) for their portfolio companies. This information allows us to distinguish between these PEFs and those who simply did not wish to respond. On the other hand, the information is not useful for the regression itself, which is used to determine the role of the PEF when it forms such a type of alliance. We therefore only include those PEFs which in fact do so.

For the same reason, our regression will not take into account modality 0 (not relevant) for the independent variables when it co-occurs with category 0 for allin/allex. Note that category 0 for the independent variables covers two different kinds of information. Either the respondent has indicated 0, thus “not relevant”, because the independent variable is not relevant to them, or because, while that variable is relevant to them, it is not so in a general sense because they do not form that kind of alliance. For example, if we raise the question of the impact of taking a majority stake on the formation of “intra” alliances, the respondent may indicate “not relevant” because they do not take majority stakes. They may also indicate “not relevant” because they only form “extraportfolio” alliances.

3.2.1.3.1. Ideal scenario and difficulties encountered

The ideal scenario is being able to test, by means of the intreg function or the ordered logit/probit function, the impact of the whole set of independent variables on the dependent variable, considering their character as qualitative over several modalities, except for the variable “Diff”, which is binary.

Due to our small sample size (50 questions were usable for testing the set of variables for allin, and 59 for allex) and the high number of independent variables and control variables over five modalities, the number of iterations for the software to calculate is so high that it may produce unexpected results. A first, quick solution might be to use different software to Stata, since software may use different algorithms. However, the problem could not be resolved in this way. Different solutions might thus be envisaged that we will explain in the following section.

3.2.1.3.2. Solutions envisaged

There are four main paths to resolving the problem posed. They are presented in order of priority. That is, if solution 1 is satisfactory, then it will not be necessary to test the other solutions. The order of priority is set so as to privilege the solutions which allow us to lose as little information as possible, while still treating the different variables in an appropriate fashion according to their nature. The possible solutions are as follows:

- 1) reducing the number of modalities to calculate per independent and control variable, by regrouping the modalities when it makes sense based on their frequencies;

- 2) performing multiple regressions; each only involving one part of the variables instead of integrating all the variables into a single regression. In view of our theoretical approach, we might then envisage carrying out three regressions: one with the contractual variables, one with the knowledge-based variables and a third regrouping the variables stemming from hypotheses comprising two subhypotheses (one based on a contractual argument, the other on a knowledge-based argument);

- 3) a combination of (1) and (2);

- 4) finally, if the problem still persists, a solution might be to test, for some independent variables or control variables, whether treating them as quantitative instead of qualitative with several modalities does not significantly affect the final result. If this is the case, one might then envisage making tests dealing with the whole set of independent and control variables as quantitative and only retaining the significant variables. We would then re-conduct the regression, treating the remaining variables as qualitative over several modalities so as to be able to interpret them more correctly. This solution is, however, only acceptable if (a) the quantitative version gives results similar to those of the qualitative version over several modalities and if (b) the number of non-significant variables to be removed from the model is high enough that the software can perform the calculations treating the remaining independent and control variables as qualitative over several modalities.

3.2.1.3.3. Final scenario chosen

We begin by testing the first solution and stopping there if it allows us to surmount the difficulties encountered. On the basis of the frequency tables for the modalities of the independent variables and control variables, we began by regrouping into a single category the negative modalities (in terms of the evaluation of impact) which were less frequent over the whole set of variables (1 and 2), as well as the positive modalities (4 and 5), where it made sense to do so. However, this was not enough for Stata to be able to carry out the regression for intreg as for the ordered logit/probit. Despite the loss of information, we had to strictly regroup all the positive modalities on one side and negatives on the other side for all our variables for the software to be able to carry out the calculations4. This was necessary for all our independent and control variables except for the “Diff” variable which is binary.

These regroupings were sufficient to find a solution for intreg, the regression by intervals. In contrast, for ordered logit/probit, we had to move on to supplementary regroupings or proceed with three regressions.

Moreover, even if it is possible in principle to econometrically model our problem by means of an ordered logit or an ordered probit, we must nevertheless ensure that our data do not reject the assumption of equality of slopes (“parallel regression assumption”, or “proportional odds assumption” in the case of logit). In fact, the two models are based on the strong assumption that the coefficients of the variables are identical, independent of the level of the dependent variable, while the constants differ [LON 01, pp. 150–152; ROU 09, p. 54]. To test whether our data satisfy this hypothesis, two tests can be performed [LON 01, p. 151]. These are the Wolfe and Gould test [WOL 98] and the Brant test [BRA 90]. The first verifies the hypothesis through the model considered as a whole. The second, Brant’s, goes further, verifying the hypothesis for each variable taken individually. The Brant test cannot be carried out on our data since the modalities of our variables are too sparsely populated and thus the test does not apply.

The first test shows us that when we chose to consolidate even more modalities so as to carry out a single regression on our data, the assumption of equality of slopes is not violated. In the case where we use three regressions while preserving several modalities, two of these regressions do not satisfy the assumption of equality of slopes. In which case, we cannot then use ordered logit or probit for these regressions [LON 01, p. 152]. We thus decided to not retain the possibility of resorting to three regressions, even though it is possible to apply in the case where the results lead us to reject the hypothesis of equality of slopes, some models of ordered logit and probit being designed to not have to meet this hypothesis. These are the models [LON 01, pp. 168–170]:

- – generalized ordered logit;

- – stereotype ordered regression model;

- – continuation ratio model.

This solution is however excluded, as decomposing our principal regression into three regressions does not allow us to make a direct comparison of our independent variables over the dependent variable. Further, that would require in our case a decomposition into a “normal” ordered logit/probit for the regression satisfying the assumption of equality of slopes, and two adapted logit/probits so as not to have to satisfy the hypothesis of equality of slopes, which would make it difficult to compare results. Moreover, since the application of ordered probit on the whole set of our independent variables, with a more concentrated regrouping of the modalities, leads to violating the assumption of normality of residuals, we will continue only with regression by intervals. It should however be noted that, independently of the difficulties encountered with implementation of ordered logit/probit, regression by intervals seems the most appropriate for the dependent variable5, given its characteristics.

To use the intreg function, it is necessary to define left- and right-censoring for the intervals of our dependent variables (allin and allex)6. Having done this, we can in principle proceed to the regression. Before continuing, however, it is necessary to check certain assumptions:

- – the absence of multicollinearity between the independent and control variables;

- – the assumption of normality of residuals;

- – the assumption of homoskedasticity of residuals.

Note that, because of the small size of the sample and the fact that these observations are divided into several modalities for the independent variables, we will see that even after proceeding to consolidation of the positive and negative modalities for our independent variables, some categories are still too sparsely populated (sometimes with only one or two observations). Inevitably, this skews our results and led to the rejection of the three hypotheses. Accordingly, before implementing the final regression, we took the decision to only compare the modality corresponding to the hypothesis being tested to the consolidated set of all the other modalities. The results of the three tests of hypotheses which follow are based on these regroupings.

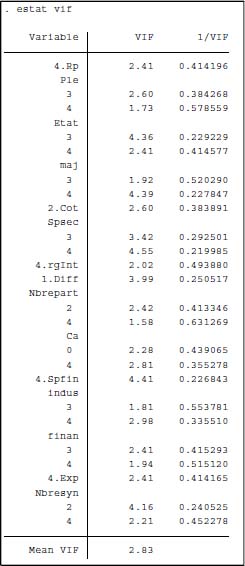

Verification of the absence of multicollinearity

“Collinearity” means that two variables are, to a certain extent, linear representations of each other. We speak of multicollinearity when more than two variables are involved. The higher the degree of multicollinearity, the more it may disrupt the estimation of the coefficients of the model and lead to biased conclusions. It is thus necessary to ensure that the problem is not too great.

The test which allows us to verify the absence of multicollinearity (or, rather, whether it is at an acceptable level) between the variables consists of calculating the variance inflation factors (VIFs) [HOE 70] of the different independent and control variables. It measures the increase in the error term of the model due to the correlation of one variable with the others. The higher the VIF, the stronger the multicollinearity. The idea of calculating the VIF is as follows: each independent and control variable is regressed on the others starting with a linear regression. The coefficient of determination (R2) of each of these regressions then indicates whether there is a linear relationship; in that case, R2 will be equal to 1. The tolerance of these models is expressed by (1 – R2) [GUJ 04, p. 356]. For example, when R2 = 1, there thus being a linear relationship between two or more variables, the degree of tolerance is 0 (1-1). The VIF is equal to 1/(1 – R2). The higher the VIF, the greater the amount of multicollinearity. If we go back to the example of an R2 equal to 1, the VIF in fact tends toward infinity (1/0). It is useful to declare the presence of multicollinearity when one VIF is greater than or equal to 10 [CHA 06, p. 238] and/or the average of the VIFs is greater or equal to 2 [DE 12, p. 6]. Alternatively, it is also possible to detect multicollinearity via the matrix of correlations [DE 12, p. 6]. Here, we present the calculation of the VIFs.

Figure 3.2. Test of multicollinearity over the variables treated as qualitative based on the calculation of the VIFs for allin

In calculating the VIFs for our independent and control variables, by definition, the VIFs are generated by modality for each variable7. Figure 3.2 gives an overview of the VIFs per modality per variable, as an example, for our data from the allin regression. Note that this test requires us to perform a linear regression on our data. The intreg function does not allow the software to calculate the VIFs.

According to the table, we do not find any VIFs greater than or equal to 10 (the highest value is 4.55). On the other hand, the average of the VIFs is slightly more than 2 (for the VIFs of our model, it equals 2.83). Even if, often, only the threshold of 10 is used, which leads to conclude the absence of significant multicollinearity for our variables, the average VIF indicates a slight presence of multicollinearity. The same applies for the data of the allex regression. We thus conclude that the coefficients of our variables and of their modalities run the risk of being biased and that they should be interpreted cautiously.

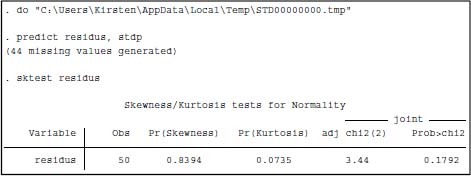

Verification of the assumption of normality of residuals

Intreg (just like the MCO linear regression) assumes that the residuals follow a normal distribution. Thus, we must verify that our data satisfy this hypothesis. Normality of the residuals ensures that the p-values of the t-test and the F-test are not biased8. Figure 3.3 shows the results of the test for the allin regression.

Figure 3.3. Testing the normality of residuals for allin

The null hypothesis to be tested is that of the normality of the residuals. The results of the test lead us to not reject the hypothesis of normality of the residuals for allin. The same applies for the data of the allex regression.

Verification of the absence of heteroskedasticity

Classical linear regression, like regression by intervals, supposes that the variance of the error term, of which we have just verified the normality, is constant, in which case we speak of homoskedasticity (homogeneous dispersal). Otherwise, we are in the presence of heteroskedasticity (“heterogeneous dispersal”). The presence of heteroskedasticity consequently means that the estimators of the regression may be biased. Interpreting the data without taking this problem into account may therefore lead to erroneous conclusions.

Note that the test for heteroskedasticity9 can only be carried out on a linear regression, and not on intreg or a tobit in general. The test is thus carried out based on a linear regression over our categorical data. For allin, it gives the following result (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4. Test of heteroskedasticity for the linear regression over allin

This involves the Breusch–Pagan test that tests the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity. Given the result obtained, we cannot reject this hypothesis and we conclude the absence of heteroskedasticity for our data. The same applies for the data of the allex regression.

We will now proceed to the interpretation of the results. However, we must be aware of the relative fragility of these results due to:

- – the small size of our sample, of the distribution of these observations over different modalities for our independent variables and of a high number of variables to test;

- – The possible presence of multicollinearity, even if it seems close to the acceptable limits;

- – the approximation made for the test for heteroskedasticity.

3.2.1.4. Results of the study and interpretation

We first present the results of the regression on the intra alliances data (section 3.2.1.4.1), then those of the regression on the extra alliances data (section 3.2.1.4.2). The last section is devoted to a comparison of the results of the two regressions (section 3.2.1.4.3).

3.2.1.4.1. Regression on the intra alliances data

To recap, out of the 77 PEFs that replied to the questionnaire, 60 indicated that they were involved with the formation of intraportfolio alliances. This phenomenon involved, in a little less than half the cases, 10% or less of the companies that they supported. It mainly involved alliances motivated by the establishment of customer–supplier relations, exchanges of organizational practices or the international development of companies. Nearly a quarter of these alliances remained informal. Apart from that, they mostly took the form of sales agreements. The PEFs indicated that they mainly intervened by facilitating the first exchanges between the partners in alliances, raising the idea of the alliance and providing contacts. Out of the 60 questionnaires completed by the PEFs involved in the formation of intraportfolio alliances, 50 turned out to be usable for the application of the regression.

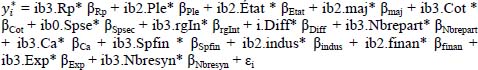

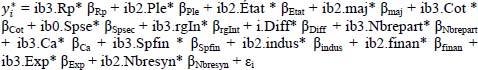

We apply the regression by intervals for the variable allin. This regression takes the following form10:

where:

- –

: the values observed by intervals for the allin data (intraportfolio alliances);

: the values observed by intervals for the allin data (intraportfolio alliances); - – Rp: reputation of the PEF;

- – Ple: presence of a competitiveness cluster;

- – État: presence of the State;

- – Cot: publicly traded status of the companies taking part in the alliance;

- – Spse: sectoral specialization of the PEF;

- – rgInt: regional/international specialization of the PEF’s investments;

- – Diff: the fact that the formation of alliances constitutes a point of differentiation for the PEF on the private equity market;

- – Nbrepart: number of companies managed by the investment manager;

- – Ca: the number of seats held on strategic boards (board of directors, supervisory board or other strategic boards) by the PEF;

- – Spfin: specialization of the PEF’s investments in terms of the stage of development of the SMEs being supported (startup, venture, growth, turnaround, etc.);

- – indus: membership of the PEF in an industrial group or company;

- – finan: membership of the PEF in a financial group (for example a bank);

- – Exp: the experience of the director of investment;

- – Nbresyn: the number of partners in syndication with the PEF;

- – εi: the error term.

Note that the reference base11 from which the coefficients of the other modalities of the different independent variables are calculated is not always the same. Sometimes it is category 3, sometimes category 2 or even category 012. The reference base is chosen variable-by-variable, in order to be able to read the coefficient of the modality in a direct link with the research hypothesis. For example, for the variable Rp, we predict a positive impact of the PEF’s reputation on the formation of alliances. We thus wish to read at least the coefficient of modality 4, corresponding to this positive impact. So we oppose it to the other modalities which, after consolidation, are included in modality 3.

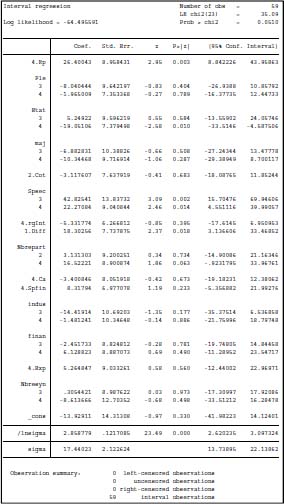

Figure 3.5 gives an overview of the results of the regression by intervals.

The χ2 probability of 0.15 indicates that this model is not statistically significant at the usual minimum level of 10%. At lower right, we see that none of our observations were censored, either to right or to left. The whole set of observations were “censored” by intervals.

Figure 3.5. Application of the regression by intervals for allin

The table itself shows, for each independent variable, the coefficients obtained for their different modalities. The interpretation of these coefficients is performed in the same way as for a linear regression. However, the table does not indicate the overall coefficient for the set of different modalities of the variables13. To do this, we must proceed to complementary tests, to see which are the variables that are globally significant14. We will then be able to assess the impact of the different modalities for the significant variables.

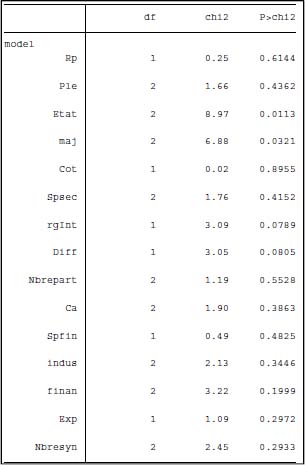

The overall coefficients for the independent variables (after application of the contrast command) are shown in Figure 3.6.

Figure 3.6. Overall significance of the independent variables for allin

In this figure, we see that only the variables Etat and maj appear to be significant at the 5% level. The Diff and rgInt variables are significant at the 10% level.

As the overall significance of the model is greater than the level of 10% (χ2 of 0.15), we tried to improve it by removing the less significant variables. Removing the variable Cot (the least significant variable) had virtually no impact on the coefficients of the other variables and the overall significance of the model remained higher than the level of 10% (0.12). Removing the variable Rp (the least significant after Cot) had no more influence on the significance of the other variables and allowed the model to be significant at the level of 10% (χ2 of 0.1). Pursuing this approach led to then eliminating the variable Nbrepart, which brought the overall significance of the model to under the 10% level (χ2 of 0.07). However, in this case, the coefficients of the remaining variables were affected.

With the 10% level significance having been reached for the model shorn of the two variables Cot and Rp, it was left for us to interpret the results from this model. However, in light of the weak impact on the overall model of the removal of these two variables, we decided to interpret the results given in Figure 3.3, including all the variables. The bias resulting from this choice was likely low.

The only variables appearing significant at the 5% level were the variables Etat and maj. We start with the variable maj (taking majority stakes). We had predicted a positive relationship between taking majority stake and forming intraportfolio alliances. For the variable maj, two modalities are reported in Figure 3.3: modalities 3 (“neutral impact”) and 4 (“positive impact”). The coefficients associated with these two modalities are calculated in relation to the modalities “not relevant” and “negative impact”, which are de facto consolidated. Modalities 3 and 4 both appear to be significant at the 5% level.

The interpretation of these modalities is as follows: compared to those PEFs who were not involved in or indicated a negative impact of taking majority stakes on the formation of intraportfolio alliances, companies involved with PEFs who mentioned a neutral impact (modality 3) or a positive impact (modality 4) formed a lesser percentage of intraportfolio alliances (the coefficients of modalities 3 and 4 are negative). This result is contrary to the hypothesis proposed. This latter is therefore rejected.

For the variable Etat, we also predicted a positive impact of the presence of the State on the formation of alliances. Figure 3.5 again shows modalities 3 and 4 for the variable Etat. The coefficients of these modalities are calculated in opposition to the remaining modalities, “not relevant” and “negative impact”. Modality 3 appears insignificant at the 5% level. On the other hand, modality 4 appears significant at the 1% level. In comparison with the PEFs who replied “not relevant” or “negative impact” for the presence of the State on the formation of intraportfolio alliances, PEFs who indicated a positive impact tended to have a lower percentage of companies in their portfolio forming alliances of the intra type. Again, this leads us to reject the proposed hypothesis.

The variable Diff (differentiation), significant at the 10% level, has a coefficient which conforms with what was predicted by the theory: there is a positive link between the fact that a PEF differentiates itself on the private equity market by the formation of alliances, and the formation of alliances for its portfolio companies, which conforms to intuition.

The same is true for the variable rgInt, which measures the impact of regional/international specialization of the PEF’s investments on the formation of alliances. The variable is significant at the 10% level. The interpretation of the coefficient of modality 4 (significant at the 10% level) apparently supports the impact predicted by the theory. Thus, compared to the PEFs who responded “not relevant”, “negative impact” or “neutral impact”, the PEFs who responded “positive impact” (modality 4) show a higher percentage of companies in their portfolio forming intra alliances. However, we cannot conclude from this that the coefficient of the variable rgInt supports the predicted theoretical link. According to the latter, remember, on the one hand, a PEF investing primarily at the regional level would have a positive impact on the formation of sectoral and often regional alliances; while on the other, a PEF investing in various countries would tend to be involved in the formation of a greater number of alliances with the goal of international development of the supported companies. Now, we only have information concerning the impact on the formation of intra/extra alliances, without being able to distinguish the sectoral or international character of the alliance.

We can see that modality 4 of the variable finan seems equally significant in the table in Figure 3.5. However, the variable as a whole is not significant, as can be seen in Figure 3.6.

Table 3.1 sums up the significant results obtained, with confirmation or rejection of the hypothesis.

Table 3.1. Summary of the significant results obtained for allin with confirmation or rejection of the hypothesis

| Allin regression | Level of significance | Sign of coefficient | Expected sign | Acceptance/ rejection of the hypothesis | |

| Model as a whole | 10% (after removal of the insignificant variables Cot and Rp) | ||||

| Hypothesis | Independent variables | ||||

| H3 | Etat | 5% | + | Rejection of hypothesis | |

| modality 3 (“neutral impact”) | 5% | – | |||

| modality 4 (“positive impact”) | 5% | – | |||

| H4 | maj | 5% | + | Rejection of hypothesis | |

| modality 3 (“neutral impact”) | 5% | – | |||

| modality 4 (“positive impact”) | 1% | – | |||

| H7b | rgInt | 10% | + | Tends to support the hypothesis | |

| modality 4 (“positive impact”) | 10% | + | |||

| H9 | Diff | 10% | + | + | Acceptance of the hypothesis |

| Etat: the presence of the State in the PEF’s capital. Maj: taking majority stakes. rgInt: regional/international specialization of the PEF. Diff: the motivation of differentiation on the private equity market by the PEF. |

|||||

3.2.1.4.2. Regression on the extra alliances data

71 out of the 77 PEFs who responded to the questionnaire indicated that their portfolio companies formed extraportfolio alliances. For almost a third of these PEFs, this comprised between 11% and 50% of the companies they supported. A quarter of these companies indicated that more than half of the companies in their portfolio formed alliances of the extra type. These alliances thus seem more frequent than in the case of intraportfolio alliances.

Extraportfolio alliances mainly have the goal of developing customer–supplier relations. From this comes the joint development of new products/services and of the company at international level. These alliances may take all kinds of forms. In more than a quarter of cases, it involves sales agreements. The PEFs reported being involved mainly by contributing contacts, facilitating the first exchanges between future partners, or by introducing the idea of the alliance. Occasionally, they may determine the choice of partner in the alliance or intervene in negotiating the terms of the alliance contract. Out of the 71 questionnaires that dealt with the formation of extraportfolio alliances, 59 were usable.

We apply the regression by intervals for the dependent variable allex. This regression takes the following form15:

where:

- –

: the values observed by intervals on the data of allex (extraportfolio alliances);

: the values observed by intervals on the data of allex (extraportfolio alliances); - – Rp: reputation of the PEF;.

- – Ple: presence of a competitiveness cluster;

- – État: presence of the State;

- – Cot: publicly traded status of the companies taking part in the alliance;

- – Spse: sectoral specialization of the PEF;

- – rgInt: regional/international specialization of the PEF’s investments;

- – Diff: the fact that the formation of alliances constitutes a point of differentiation for the PEF on the private equity market;

- – Nbrepart: number of companies managed by the investment director;

- – Ca: the number of seats held on strategic boards (board of directors, supervisory board or other strategic boards) by the PEF;

- – Spfin: specialization of the PEF’s investments in terms of the stage of development of the SMEs being supported (tartup, risk, development, turnaround, etc.);

- – indus: membership of the PEF in an industrial group or company;

- – finan: membership of the PEF in a financial group (for example a bank);

- – Exp: the experience of the director of investment;

- – Nbresyn: the number of partners in syndication with the PEF;

- – εi: the error term.

Figure 3.7 gives an overview of the values of the coefficients of the modalities of the independent variables.

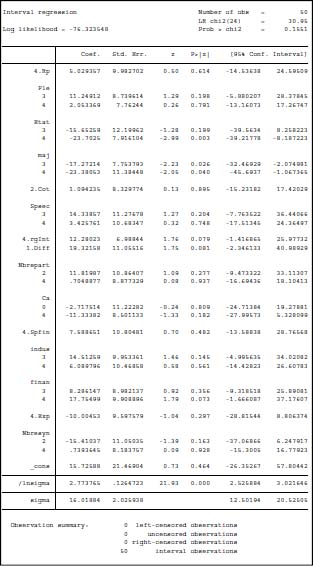

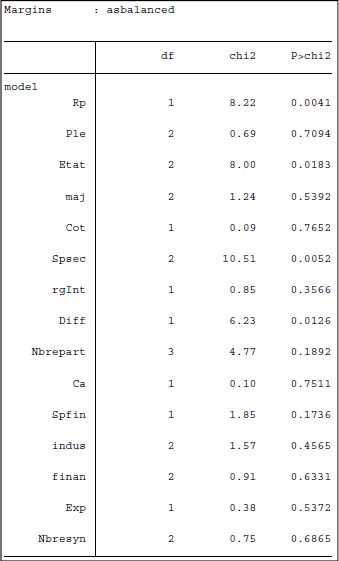

The regression as a whole is this time significant at the 5% level with a χ2 probability of 0.05. To the lower right, we can read that none of our observations is censored to left or to right. The whole set of observations is essentially “censored” by intervals. Before interpreting the values of the table, we again concern ourselves with the overall significance of the independent variables (Figure 3.8).

Four variables appear to be significant overall (without distinguishing the modalities). These are variables Rp (at 1% level), Spsec (at 1% level), Etat (at 5% level) and Diff (at 5% level).

Figure 3.7. Application of the regression by intervals for allex

Figure 3.8. Overall significance of the independent variables for allex

Although the model is significant at the 5% level, we have also attempted to see if this significance could be substantially improved by removing the less significant variables. Thus, by removing successively the variables Cot (publicly traded status of the companies forming the alliance), Ca (the presence of the PEF in the strategic boards such as the board of directors or the supervisory board), Ple (the presence of a competitiveness cluster), Exp (the experience of the director of investment), Nbresyn (the number of partners in syndication of the PEF) and finan (the specialization of the PEF’s investments according to the stage of development of the supported companies), the global model becomes significant at the 1% level (χ2 of 0.0048), without these removals significantly affecting the other variables.

As for the intraregression, given these results, we base our interpretation on Figure 3.7, which presents the values of the coefficients associated with the modalities of the different variables without removing any variable.

For the variable Rp, the coefficient of modality 4 appears significant at the 1% level. This allows us to conclude that the PEFs who reported a positive impact for reputation on the formation of extraportfolio alliances create a higher percentage of these for the companies in their portfolio, in comparison to the PEFs who replied “not relevant”, “negative impact” or “neutral impact”, which confirms the hypothesis.

For the variable Etat, modality 4 appears significant (5% level). According to its coefficient, we can conclude that, in comparison to the PEFs who responded “not concerned” or “negative impact” to the presence of the State in the formation of extraportfolio alliances, the PEFs who indicated a positive impact tend toward a lower percentage of companies in their portfolio forming this type of alliance. This result contradicts the hypothesis advanced.

Modalities 3 and 4 of the Spsec variable seem significant (at levels of 1% and 5%, respectively). Compared to the PEFs who indicated “not relevant” or “negative impact” to sectoral specialization of the PEF on the formation of extra alliances, those who mentioned a neutral or positive impact report more companies in their portfolio forming extraportfolio alliances. However, we must make the same reservation as for the rgInt variable when interpreting the results for the intra data. Overall, the positive relationship between sectoral specialization of the PEF and the formation of intra alliances goes in the direction expected at the theoretical level. However, though we predicted a positive link between the sectoral specialization of the PEF and the formation of a certain type of alliance (sectoral alliances), we do not possess the information allowing us to really test this hypothesis.

The variable Diff is significant at the 5% level and, according to its coefficient, the PEFs for which the formation of alliances is a means of differentiation on the private equity market show a higher level of supported companies forming extra alliances, compared to other PEFs. This result conforms to the predicted link.

Note that modality 4 of the variable Nbrepart also appears significant in the table in Figure 3.7. However, the variable as a whole is not significant, as can be seen in Figure 3.8.

Table 3.2 sums up the significant results obtained, with confirmation or rejection of the hypothesis.

Table 3.2. Summary of the significant results obtained for allex with confirmation or rejection of the hypothesis

| Allex regression | Level of significance | Sign of coefficient | Expected sign | Acceptance/ rejection of the hypothesis | |

| Model as a whole | 5% (or 1% after removal of insignificant variables) | ||||

| Hypothesis | Independent variables | ||||

| H1 | Rp | 1% | + | + | Acceptance of the hypothesis |

| modality 4 (“positive impact”) | 1% | ||||

| H3 | Etat | 5% | – | + | Rejection of hypothesis |

| modality 4 (“positive impact”) | 5% | ||||

| H7a | Spsec | 1% | + | + | Tends to support the hypothesis |

| modality 3 (“neutral impact”) | 1% | ||||

| modality 4 (“positive impact”) | 5% | + | |||

| H9 | Diff | 5% | + | + | Acceptance of the hypothesis |

| Rp: the reputation of the PEF. Etat: the presence of the State in the PEF’s capital. Spsec: the sectoral specialization of the PEF. Diff: the motivation of differentiation on the private equity market by the PEF. |

|||||

3.2.1.4.3. Comparison of the roles of PEFs between intra and extraportfolio alliances

The comparison of the roles of PEFs according to the type of alliances formed, intra or extra, confronts several limitations:

- – a difference of degree of significance between the allin and allex regression (respectively, significant at the 10% level after removing two variables and at the 5% level, even 1% after removing several variables);

- – the potential presence of multicollinearity for our data that may bias the results, even if it seems that this multicollinearity is relatively weak;

- – the small size of our samples and the large number of variables, which suggests a weak robustness of the results obtained.

We will, nevertheless, try to draw up a conclusion and to reconcile the results obtained. Remember that, as the questionnaire intended for SMEs never took place, the results that we are interpreting compare, on the one hand, the perception that the PEFs have of the impact of the different independent variables on the activity of forming alliances among their portfolio-companies, and, on the other hand, the real percentage of their portfolio-companies who have formed an intra- or extraportfolio alliance, as indicated by the PEF.

For intraportfolio alliances, only two variables appear to be significant: Etat (state involvement) and maj (the PEF taking majority stakes). The variable maj appeared significant for the regression on allin, and not significant for the allex regression. The first results conform to the hypothesis advanced; an assumed positive effect of taking majority stakes on the formation of intraportfolio alliances. On the contrary, the expected sign of maj on the formation of intra/extra alliances is contrary to what we expected.

The variable Etat is significant in both allin and allex regressions and shows the same effect for both regressions – contrary to what was predicted by the theory. This result thus reverses the hypothesis presented. In addition, note that the hypothesis predicted a positive impact of the presence of the State or of a competitiveness cluster on the formation of alliances. Now, only the variable Etat seemed significant in the two regressions, but with a reverse relationship to what was expected.

As for the variable Ple (presence of a competitiveness cluster), it was not significant for either regression. The negative impact of the presence of the State on the formation of alliances, nevertheless, seems curious. Even if it does not have the positive impact expected, we would have then imagined a neutral rather than a negative impact.

The variable Diff (differentiation of the PEF on the private equity market), significant in the allin regression at the 10% level and in the allex regression at 5%, shows, in both cases, the expected sign implying a positive link between the strategy of differentiation through the formation of alliances by the PEF on the private equity market and the percentage of supported companies forming extraportfolio alliances.

One last variable seems significant for the allin regression: the variable rgInt (regional/international specialization of the PEFs) at the 10% level. Its sign (positive) agrees with the hypothesis presented, even if we must be very careful in interpreting this variable in the light of the hypothesis presented, as it does not really allow us to test that hypothesis. The latter actually predicts a positive link between regional or international specialization in the PEF’s investments and the formation of alliances of, respectively, regional or international scope. Now, we can only interpret the impact of the variable on the formation of intra- or extraportfolio alliances. Moreover, we did not predict differences in the case of formation of intra or extraportfolio alliances. Now, the variable appears significant for the allin regression with a positive sign, and not significant for the allex regression with a negative sign.

The variable Rp (the reputation of the PEF) appears significant in the allex regression. It is quite interesting to compare this with its significance for the intra regression. There it did not appear as significant, whereas in the extra regression, Rp is significant and indicates a positive link with the formation of extraportfolio alliances. However, in the intra regression, the sign of Rp is also positive. This reinforces, at least in part, the hypothesis that predicted a positive link between the reputation of the PEF and the formation of alliances, as well as the arguments advanced that the link between the reputation of the SCI and the formation of alliances would be more direct in the case of forming extraportfolio alliances.

Finally, the variable Spsec (sectoral specialization of the PEF) indicates a positive link between sectoral specialization of the PEF and the formation of extraportfolio alliances. Positive coefficients are found both for intra and for extraportfolio alliances, although the variable does not appear to be significant. We may thus conclude a favorable tendency toward the hypothesis even if, for reasons similar to those expressed for the rgInt variable discussed above, we cannot entirely establish the acceptance or the rejection of the hypothesis presented, given that we have not really been able to test it. This latter predicted a positive link between sectoral specialization of the PEF and the formation of sectoral alliances. However, we do not possess information about the formation of sectoral alliances.

Table 3.3 summarizes these different points. It presents the results for the significant variables of the allin and allex regressions, compares these results in terms of significance and the sign of the variables, and indicates whether the theoretical hypothesis is rejected or not.

Table 3.3. Summary of the results for the significant variables of the two regressions allin and extra

| Hypothesis | Regression | Level of significance | Sign of coefficient | Expected sign | Acceptance/ rejection of hypothesis | ||

| Independent variables | Allin | Allex | Allin | Allex | |||

| H4 | maj | 5% | + | Rejection of hypothesis | |||

| modality 3 (“neutral impact”) | 5% | – | – | – | |||

| modality 4 (“positive impact”) | 1% | – | – | – | |||

| H3 | Etat | 5% | 5% | + | Rejection of hypothesis | ||

| modality 3 (“neutral impact”) | 5% | – | – | + | |||

| modality 4 (“positive impact”) | 5% | 5% | – | – | |||

| H7b | rgInt | 10% | – | + | Unable to reach a conclusion | ||

| modality 4 (“positive impact”) | 10% | – | + | – | |||

| H9 | Diff | 10% | 5% | + | + | + | Acceptance of the hypothesis |

| H1 | Rp | – | 1% | + | Acceptance of the hypothesis | ||

| modality 4 (“positive impact”) | – | 1% | + | + | |||

| Spsec | – | 1% | + | Tends to support the hypothesis | |||

| modality 3 (“neutral impact”) | – | 1 % | + | + | |||

| modality 4 (“positive impact”) | – | 5 % | + | + | |||

| Maj: taking majority stakes. Etat: presence of the State in the PEF’s capital. rgInt: regional/international specialization of the PEF. Diff: the motivation of differentiation on the private equity market of the PEF. Rp: the reputation of the PEF. Spsec: sectoral specialization of the PEF. |

|||||||

It remains to compare the overall results of the allin and allex regressions to test Hypothesis 10. According to the latter, PEFs play more important roles in the case of formation of intraportfolio alliances than extraportfolio alliances. Our results do not allow us to confirm this hypothesis.

Finally, taking account of the fragility of the results obtained, it seems that we must be very careful as to the conclusions to be drawn. This fragility further justifies the use of multiple case studies to reinforce or not the conclusions of the econometric study.

The entirely provisional conclusions, which it seems possible to draw, however, seem to be as follows:

- – PEFs who differentiate themselves on the private equity market by the formation of alliances have a higher level of supported companies who form extraportfolio alliances and, possibly, also intraportfolio alliances;

- – the reputation of PEFs has a positive impact on the formation of extraportfolio alliances;

- – the presence of the State seems to have a negative impact on the formation of alliances;

- – based on only the results of the econometric study, we cannot conclude that greater roles are played by PEFs in the case of the formation of intraportfolio alliances (as opposed to extraportfolio alliances).

3.2.2. Multiple case study

We begin by explaining the purpose and nature of the study (section 3.2.2.1) as well as the procedure for choosing the fields for the cases (section 3.2.2.2), before presenting them (the fields and the cases). We will then describe the data sources to which we had access (section 3.2.2.3), then explain the way in which we carried out our analysis (section 3.2.2.4). The analysis itself is found in section 3.2.2.5. We finish with the conclusions that we were able to draw from this study (section 3.2.2.6).

3.2.2.1. The purpose and nature of the case study

In the statistical and econometric analysis, we tested the general nature of the hypotheses derived from our theoretical concept, the parent population being French PEFs. This case study will now allow us to proceed to an analytical test of generalization, that is, to see if empirical results support a previously established theory, to determine whether the mechanisms of causality, advanced in theory, are plausible. In other words, the statistical and econometric study allowed us to verify empirically that there is indeed a correlation in the predicted direction between the independent variables and the dependent variable. It now remains to verify the plausibility of the causal mechanisms which explains the links between these variables. Using a case study methodology brings two additional benefits. First, it allows us to verify the explanations advanced from the point of view of the SMEs forming an alliance, as well as the point of view of the PEFs. This is not possible using a statistical approach, because it involves two different visions for the same, statistically identifiable empirical result. Taking into account different points of view allows a triangulation of data [GRA 07, p. 28; GIB 10, pp. 712–713]. Second, it offers the possibility, by combining it with the statistical and econometric study, of triangulating the methods used.

The study consists of a multiple case study with explanatory design16 which is also “embedded” [YIN 09, p. 59]. “Multiple” means it includes more than one case (eight in total), in order to increase both its internal and external validity, through the possibility of replication. This allows us, in the end, to be able to claim with greater certainty an analytical generalization of the results of the study. The term “embedded” signifies that we are taking into account different perspectives for the same unit of analysis. This is justified for two reasons. On the one hand, we take into account two points of view in our theoretical analysis: that of the SMEs forming the alliance, and that of the PEF. As opposed to statistical and econometric studies, case studies allow us to take account of such an aspect, and this is one of the reasons why we use them. In our study, therefore, we question the managers of companies supported by private equity as well as the PEFs for the same alliance. On the other hand, collecting different points of view allows us, again, to reinforce the robustness of our results if the results from the different points of view converge.

Multiple and embedded case studies, according to Yin [YIN 09, p. 59], are the most complex to design, as the selection of cases must be made in such a way that all the criteria arising from the theoretical concept are represented. To qualify as a literal replication, it is necessary to choose “fields of study/analysis” which may contain several similar cases. In our case, the field of analysis consists of a PEF and its portfolio of investments. It is necessary, moreover, that the PEF can provide at least two examples of alliances being formed (or in the process of formation) by its portfolio companies. This constitutes a first difficulty, as it means that it is not only necessary to find French PEFs presenting some of the sought-after characteristics arising from our research hypotheses, but also to ensure in advance that each field contains two similar cases, in order to enable literal replication not only between the fields, but also within the same field. The examples of alliance formation with which these PEFs provide us therefore constitute the cases, properly speaking. For example, let us take the variable “taking majority stakes” which arises from our research Hypothesis 4. We must then choose two PEFs taking majority stakes, to be able to proceed to replication between the fields. Moreover, each of these PEFs must be able to provide us with two examples of formation of alliances, in order to be able to proceed to literal replication within a single field. This all becomes more complicated when we realize that, while using as few fields (PEFs) as possible, the whole set of variables arising from our hypotheses must be represented in this way.

The study is dynamic in nature. The period of study varies from case to case, as it extends over the time of the formation of the alliance which may vary in different cases. Some of the alliances studied were, furthermore, still in the course of formation at the end of our study.

3.2.2.2. Selection process and presentation of the cases and fields of study