2

The Role of Private Equity Firms in Alliance Formation from the Perspective of Value Creation

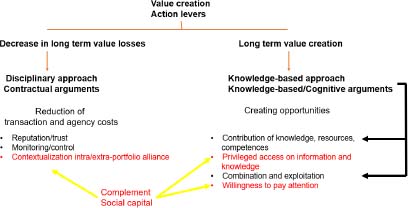

In this chapter, we refer to three theoretical frameworks in order to analyze our problem and then we apply the theory to the French market in Chapter 3. We begin our analysis with the use of contractual theories (section 2.1), and then discuss knowledge-based theories (section 2.2). The final section will turn to sociological network theories (section 2.3) with the sole aim of completing the contractual and knowledge-based argumentation.

The contractual theories we allude to include the transaction cost theory (TCT) and the positive agency theory (PAT). The so-called “knowledge-based” theories are based on strategic or heterodox economic streams. They include the resource-based view (RBV), competence-based view (CBV), evolutionary economic theory and behavioral theory of the firm. They are sometimes grouped under the term knowledge-based view (KBV). These two theoretical frameworks are part of the efficiency paradigm that allows value creation to be analyzed [CHA 06]. In light of our problem, they make it possible to analyze the role of a PEF in improving (or deteriorating) the efficiency of alliances formed, as well as the impact of a PEF on the alliance’s value creation. An organizational system (including the alliances in which we are interested here) is considered to be efficient if it maximizes organizational rent (or surplus) and if, on average, there is no alternative mechanism to achieve better results for all stakeholders [MIL 92]. This efficiency is static in design within contractual theories. The goal is to maximize the organizational rent at a given time [CHA 06]. These theories do not concern the creation of value itself but rather the limitation of value losses, at a given point in time, that result from the presence of transaction and agency costs [LAN 99, pp. 201–202]. Knowledge-based theories are based on a dynamic notion of efficiency [CHA 06]. They question the productive origin of long-term value creation. Elements that are derived from sociological network theories, but which are compatible with the efficiency paradigm (especially emanating from the notion of social capital), complete the arguments of the two frameworks.

In each of the three parts of our theoretical analysis, we have included a section that begins with a brief introduction to the main points of the theory that are relevant to our particular problem. We then apply the theory to our topic. This includes a systematic analysis from the perspective of both the SMEs that form an alliance and the PEF. More precisely, the features of SMEs supported by PE are put forward in light of key concepts that are associated with the various theoretical frameworks. They form the basis for analyzing the difficulties that SMEs may face in forming alliances. The question then arises as to whether the presence of a PEF makes it possible to overcome these obstacles. Subsequently, we consider the benefit for PEFs in forming alliances for the companies they support.

2.1. The role of PEFs from the perspective of contractual theories

In this section, we intend to shed light on our problem by turning to the theoretical streams that make up the contractual theories of organizations (hereinafter denoted TCO): TCT [COA 37; WIL 91a] and PAT [JEN 76]. They appear because of the inability of traditional neoclassical theories to explain organizational phenomena. These theories therefore make it possible to, on the one hand, understand strategic alliances and, on the other hand, analyze the role played by PEFs.

We begin by introducing some theoretical bases that will be useful for exploring our subsequent problem (section 2.1.1). We then give an overview in section 2.1.2. In section 2.13, we apply the theory to our problem. We conclude with a review of the role of PEFs in alliance formation from the perspective of contractual theories in section 2.1.4.

2.1.1. Some theoretical foundations

Contractual theories include the TCT [WIL 91a] and the PAT, which is itself based on the property rights theory [ALC 72] and on the agency relationship, which arises from the principal–agent approach, and thus from the normative agency theory. According to these theories, different organizational forms – including alliances – are defined as nexus of contracts. They are said to be efficient if they minimize transaction and agency costs at any given time. Transaction costs result from the costs of finding the counterparty to the transaction, from information costs in the ex ante phase to the establishment of the transaction and from the costs of negotiating, deciding, monitoring and executing contracts in the ex post phase to the transaction itself. Agency costs arise from conflicts of interest between the agents involved in a transaction.

Let us begin by looking at the contributions brought about by TCT (section 2.1.1.1), followed by those from PAT (section 2.1.1.2).

2.1.1.1. Contributions of TCT to contractual theories

The initial questioning of TCT arises from the existence of the firm in relation to the market. In neoclassical theory, the only mode of coordination considered is the market through prices. This raises the question of whether a firm’s existence is justified, which was initially asked by Coase [COA 37]. If a company exists, it is because there are imperfections in the markets, which creates costs. If the actors require coordination via hierarchical structures within a company, it is because this makes it possible to reduce the costs linked to market inefficiencies. The use of the market or a firm as a coordination method therefore results from an arbitration between the associated (transaction and production) costs.

Williamson extends and generalizes Coase’s analysis by constructing a general theory of markets and organizational forms: TCT. There are three key notions within this theory: transaction as a unit of analysis [WIL 91a, p. 79], the limited rationality of agents and the (potential) opportunism of actors. Limited rationality refers to the fact that individuals make decisions in a computational manner (in other words, they evaluate the consequences of different opportunities presented to them with reference to a set objective). But individuals may not seize all the alternatives presented to them and may also make evaluation errors on the consequences of choosing one of these alternatives, or may even make reasoning errors.

Since the unit of analysis within the theory is the transaction, turning to the market or a firm depends on the respective transaction costs generated by the two modes of coordination [WIL 91b, p. 269]. By defining a transaction as the transfer of the right to use an asset (good or service), one can distinguish between the costs of finding the counterparty and providing information (ex ante to the transaction) and the costs of negotiating, deciding, monitoring and executing contracts (ex post to the transaction).

In order to make the analysis functional, Williamson defined three critical dimensions of the transaction as follows [WIL 79, p. 239]:

- – asset specificity: an asset is specific if it cannot be redeployed, in other words if it loses value by being reassigned to other uses. An asset will be highly specific if it is idiosyncratic to the transaction. It is the source of a quasi-rent [WIL 79, p. 241];

- – the frequency and duration of transactions;

- – the degree of uncertainty: the greater the uncertainty, the more difficult it will be to predict and determine all possible outcomes. Drafting full contracts becomes difficult and costly.

Due to the uncertainty and potential opportunistic nature of the actors, the contracting parties to the transaction run the risk of being ripped off. This risk of being ripped off increases with specificity of assets. Since specific assets lose their value if they are reassigned to uses other than the original transaction, the seller of the asset in question can act opportunistically and increase the price of the asset once an agreement is reached. This postcontractual risk of non-performance is known as moral hazard, if it is intentional [BRO 93, p. 14]. In the precontractual phase, a contract may not be concluded because of the risk of adverse selection [AKE 70], in other words, mistrust about the quality of the potential transaction partner or the object of the transaction. The uncertainty and the limited rationality of agents make it impossible to resolve contracts in such a way as to define all possible contingencies ex ante. In order to insure against these risks and limit the associated costs, one solution is to internalize the transaction. Having to turn to the market or hierarchy then results from a production and transaction costs’ optimization problem, thus minimizing the sum [WIL 79, p. 245]. Schematically, having to turn to the hierarchy as a mode of governance (internalization) is justified for transactions that involve highly specific assets and frequent and sustainable (and therefore long-term) transactions. Conversely, turning to the market (total outsourcing) is justified for short-term, infrequent transactions that involve assets that are not very specific.

Following this reasoning, strategic alliances can be described as a hybrid mode of coordination, falling somewhere between the two extremes of market and enterprise (hierarchy) [WIL 91b]. This hybrid contract covers recurring and long-term transactions including average to highly specific assets. Due to its average to highly specific nature, turning to the market can be risky and therefore costly. On the other hand, the problem with opportunism of actors does not justify the costs of internalizing the transaction. Alliances therefore make it possible to reduce transaction costs and uncertainty while allowing companies to remain autonomous. Consequently, the contract requires a special governance mechanism [WIL 91b, p. 271]. In what follows, we discuss the role that a PEF can play.

TCT provides a preliminary justification for the existence of organizational structures. It makes it possible to gain an initial approach to alliances and then to study the role of PEFs in alliance formation. In order to take the analysis further, let us present the PAT. This theory focuses on agency relations between agents, whereas the TCT uses the transaction as the unit of analysis. Unlike in TCT, organizational structures, including alliances, are no longer seen as a black box. PAT makes it possible to analyze internal organizational structures and account for conflicts of interest between contracting parties. It makes it possible to explicitly consider the preferences or attitudes of the contracting parties toward the transaction.

2.1.1.2. Contributions of the agency theory to contractual theories

Our introduction to the contributions of the PAT is split into four sections. Section 2.1.1.2.1 presents concepts from Berle and Means, The Modern Corporation and Private Property (1932; [BER 91]). These authors analyzed the managerial enterprise, which thrived in the United States, and they highlighted the problem of emergence of conflicts of interest that resulted from a dismemberment of ownership. Section 2.1.1.2.2 highlights key concepts from Alchian and Demsetz [ALC 72]. Starting from the definition of a company as a nexus of contracts, they see companies as production teams and thus deliver, beyond the justification of their existence, an analysis to explain the different forms of organizational structures. In section 2.1.1.2.3, we look at key concepts from Jensen and Meckling [MEC 76]. Starting from an entrepreneurial company and combining elements of agency theory, property rights theory and financial theory, they attempt to develop a positive theory of the ownership structure of the firm. Section 2.1.1.2.4 briefly discusses a firm’s organizational architecture that is made possible by the agency theory.

2.1.1.2.1. Analysis of Berle and Means [BER 91]

For a company in its simplest form – an individual entrepreneur – the person who provides the capital and assumes the financial risk of the investment also has residual decision-making power. That is, he or she has decision-making authority over any matter that is not governed by contracts or by law [CHA 02a]. This same person therefore manages the company both at the operational level (providing, coordinating and exploiting production factors) and at the strategic level (identifying, even creating and implementing opportunities). This person then simultaneously fulfills three functions [CHA 02a]:

- – the risk and uncertainty assumption function;

- – the company’s leadership or management function (providing, coordinating and exploiting production factors);

- – the function of identification, even creation and implementation of growth opportunities.

In their book The Modern Corporation and Private Property, Berle and Means [BER 91] discussed the distribution of ownership within a managerial type of enterprise, which was developed in the 20th Century mainly in the United States. Contrary to sole proprietorship, ownership is so dispersed that no single owner has sufficient interests to appropriate residual decision-making power, and therefore management of the business [BER 91, p. 78]. For example, in some cases, the majority shareholder holds less than 1% of the capital [BER 91, p. 47]. The management of the company is then delegated to a group of people: the management.

A managerial type of company therefore features, on the one hand, a dispersed ownership structure such that no single shareholder holds a significant share of the capital. On the other hand, a restricted group of people – management – has the power to take decisions and manage the company [BER 91, in particular p. XXIII, p. 5, pp. 83–84, pp. 244–246, p. 297, p. 300 sq.]. Usually, this management holds little or no capital [BER 91, p. 53, p. 83].

In this type of company, the three functions mentioned above in the example of the individual enterprise are then separated. They are divided between shareholders and management. There is a dismemberment of “passive” and “active” ownership [BER 91, p. IX, p. XXIII, p. XXXV, p. 9, p. 244, p. 297, p. 300, p. 304]. Passive ownership is held by shareholders who have the sole function of providing capital and assuming risk and uncertainty. They become mere providers of capital [BER 91, pp. 245–246]. Active ownership belongs to management, which assumes the functions of leadership as well as the identification, creation and implementation of opportunities. It holds the residual decision-making rights and manages the company at operational and strategic level.

Berle and Means were particularly interested in this type of company because it appeared to be the dominant organizational structure of the 20th Century in the United States. On an economic level, the emergence of this managerial type of company gave rise to a concentration of economic power that – at least in the United States – could compete with the political power of the State [BER 91, p. 309, p. 313]. Indeed, it placed the savings of countless individuals under the centralized control of a limited number of people: management [BER 91, p. 5]. As a result, these companies required the interconnection of a wide variety of interests [BER 91, p. 310]. The depersonalization of ownership, which landed into the hands of multiple actors, and which was accompanied by the dismemberment of its functions, thus led Berle and Means to assimilate this managerial type of enterprise to an institution for which the characteristics resemble those of the State [BER 91, p. XVII, p. XXXVIII, p. 5, p. 309]. Consequently, the authors believed that this type of enterprise must be considered not as a company but as a social organization. As a result, they concluded that the consequences of decisions taken within these companies must be taken into account, not just for the owners (shareholders that have passive ownership and management that have active ownership), but for a broader category of actors including employees, customers and suppliers, and even the interests of society as a whole [BER 91, pp. 312–313]. Their approach is therefore stakeholder oriented.

The question then raised is who has the status of residual claimant and, consequently, the right to profit [BER 91, p. 293]. According to Berle and Means, profit, as a counterpart to performance, fulfills two incentive functions [BER 91, p. 300]:

- – it encourages individuals to take risks by placing their savings within the company;

- – it encourages the individual who holds the residual decision-making rights to do everything possible to make the company profitable.

Profit therefore rewards both passive and active ownership.

This distinction between the two incentive profit functions is not important in sole proprietor companies. However, it becomes significant if ownership is divided into its passive and active components, with each component being in the hands of different actors. Berle and Means concluded that, on the one hand, from an economic point of view, the status of residual claimant must not go to passive owners (shareholders). Shareholders should receive sufficient remuneration for them to keep (and continue to have) an interest in risking their savings for the company. The authors compared shareholder remuneration logic to employee remuneration logic, the latter of which must be paid in such a way that the employee is willing to provide (and to continue to provide) his or her labor. Berle and Means perceived no social efficiency benefit in allocating the organizational rent (surplus) to the shareholder since the latter has renounced active ownership – the residual decision-making power – and thus any responsibility in managing affairs [BER 91, p. 301]. On the other hand, they did not conclude that the profit should only go to active owners, in other words to management [BER 91, p. 312]. Two justifications are put forward. First, the separation of passive and active ownership creates the problem that management, having a discretionary space, might not act in line with the interests of passive owners (shareholders) [BER 91, pp. XIV–XV, pp. 113–114]. If management was granted residual claimant status and given the organizational rent, it would then have no incentive (unless it was intrinsic in nature) to guide the company’s actions to be in line with the interests of passive owners. Second, the profit generated by a company (at least in the United States) does not solely result from transactions that are initiated by active ownership and financed by passive ownership. It also comes, in part, from the company’s market position and from subsidies financed by taxpayers through the State. In this sense, the U.S. state is an investor in nearly every U.S. company. There is growing recognition that, at least for very large companies, their actions can be defined as collective transactions that are similar to transactions done by the State [BER 91, p. XXXVIII]. There is therefore no justification for granting shareholders residual claimant status [BER 91, p. XXVII].

However, the authors did point out that this conclusion needs to be taken with a pinch of salt since the separation of active and passive ownership exists to varying degrees [BER 91, p. 5, p. 6]. In reality, and particularly in European countries including France (the country of interest in this study), this separation is rarely complete. It is even the exception [CHA 06]. In these cases, shareholders also take on part of the active ownership and may be entitled to part of the profit.

In our problem, PEFs bring a lot of capital to the companies they support. However, in addition to their financial contribution, they possess skills from which their portfolio companies can benefit. PEFs are active shareholders, which is one of their key features, as we presented in our introduction to PE.

In order to resolve conflicts of interest between shareholders and management, Berle and Means proposed to implement incentive solutions [BER 91, pp. XII–XIII]. Following this realization, a whole stream developed in the literature which, from a normative perspective and based on the notion of agency relationships, sought to find solutions that encourage management (active ownership) to act in the interests of shareholders (passive ownership). Later, notably after the articles published by Alchian and Demsetz [ALC 72] and, more particularly, the article by Jensen and Meckling [JEN 76], a positive perspective developed, which sought to explain why there were different organizational configurations [JEN 76, p. 310; JEN 83, p. 334; CHA 00]. Adopting a positive approach, we are part of this second perspective. Let us now present the two key articles.

2.1.1.2.2. The firm as seen by Alchian and Demsetz [ALC 72]

For Alchian and Demsetz [ALC 72, p. 777], a theory of economic organization must be able to solve two questions:

- – it must highlight the factors that determine when hierarchical coordination (the firm) is superior to market coordination and vice versa;

- – it must explain the structure of firms and their organizational architecture.

Starting from the view of a firm as a nexus of contracts [ALC 72, p. 778], the authors highlighted two determinants [ALC 72, p. 778, p. 783]:

- – the team use of production factors (inputs) held by different agents;

- – the management of this team by an agent with a central position within the nexus of contracts.

A company is therefore characterized by its management of production factors, both in teams and centralized. This joint management allows the company to benefit from synergies resulting from group work. The centralization of management must ensure effective teamwork. Alchian and Demsetz [ALC 72, p. 783] specified and insisted on the fact that this centralized management has the vocation of a common management, per team, and not an authoritarian management that allows the central agent to exercise disciplinary power. Each team member’s relationship with the central agent is reflected in a simple contract that is based on reciprocity (“quid pro quo”, which may consist of an exchange of input such as labor or capital contribution for remuneration. This could be linked or not, for example, to the performance or output of team work).

The role of the central agent is justified by the fact that team management, on the one hand, has the consequence of being able to benefit from synergies and, on the other hand, raises the problem of free riding. Because of the difficulties in observability of individual contributions of the different inputs to output and measurability of performance, the agents involved may, if they have an opportunistic character, seek to take advantage of this situation by benefiting from the work provided by their teammates. They would then appropriate all of the gains from their behavior, while the related costs (a reduction in production) are borne by all of the members of the team [ALC 72, p. 780]. Team production then poses the problem of how to encourage team members such that all agents work efficiently [ALC 72, p. 779]. According to Alchian and Demsetz [ALC 72, p. 783], the most effective organizational structure is one that allows the central agent to fulfill the function of a “typical” arbitrator, solving to the best of their ability the problems related to group production. Such an arbitrator should have the following rights:

- – the right to be the residual claimant that receives the remaining organizational surplus after remuneration of other production factors (inputs);

- – the right to observe the contribution (input) of actors;

- – the right to be the central intermediary, common to all actors;

- – the right to elect or remove parties (team members);

- – the right to transfer these rights.

As with Berle and Means [BER 91], organizational rent does not necessarily belong to the shareholder. According to the analysis proposed by Alchian and Demsetz, it belongs to the agent who manages the company’s production factors. The manager, or active owner according to the distinction by Berle and Means [BER 91], is then assigned the status of residual claimant to whom the profit accrues. If this person is paid once all of the other agents who are contractually bound to him have been paid, this solution would constitute an incentive for the central agent to effectively manage the productivity of the team [ALC 72, p. 785].

Thus, according to this view, strategic alliances, which until now were defined as hybrid contracts between the hierarchy and the market, constitute a cooperative relationship between at least two companies. This cooperation makes it possible to achieve synergy effects due to joint production [ALC 72, p. 779]. If a PEF is a common actor to all the alliance partners, it would be useful to determine whether it can possibly play the role of central actor. We discuss this in the section on applying the theory to our research question. Before that, let us present some contributions from the article by Jensen and Meckling [JEN 76].

2.1.1.2.3. Some key points from the article by Jensen and Meckling [JEN 76]

Jensen and Meckling [JEN 76] proposed a positive theory to explain the financing structure of firms. They transposed Berle and Means’ analysis of the managerial enterprise, and the agency problem that arises there, to an entrepreneurial firm in order to analyze, through a positive approach, the incentive consequences that result from the various forms of external financing that the manager and owner of a company uses in order to make its development possible.

They begin with an entrepreneurial firm where a person who owns 100% of the structure opens his or her capital to raise funds. This person chooses external equity or debt financing. Jensen and Meckling analyzed this situation from the perspective of the PAT. In both cases, the result is an agency relationship between the entrepreneur–manager (agent) and the new shareholders or creditors (principals).

According to Jensen and Meckling [JEN 76, p. 308], an agency relationship is “a contract under which one or more persons (the principal(s)) engage another person (the agent) to perform some service on their behalf which involves delegating some decision-making authority to the agent”. Due to differences of interest between the principal and the agent, agency conflicts can arise. Within contractual theories, these conflicts of interest can be resolved through contracts and incentive systems. However, a complete and inexpensive solution to the agency problem via contracts can only occur in an environment that is characterized by certainty. In the presence of uncertainty and information asymmetry, it is too costly (if not impossible) to determine all possible contingencies in advance, which makes contracts incomplete. Incomplete contracts are risky to make. Agents, who are supposedly of limited rationality and supposed to maximize their own wellbeing, may not perform a task delegated to them properly or may act strategically, even opportunistically, once the contract is concluded. In this case, they may try to take advantage of the situation and the flaws in the contract by exploiting the private information they hold in order to pursue their own goals. One solution to this problem may be the establishment of control mechanisms. But, because of the information asymmetry, control of agent behavior by the principal cannot be done without incurring costs.

The information asymmetry exists both before and after the contract is signed and distinguishes between pre- and postcontractual risks. In the first case, precontractual risks may prevent the formation of a contract even though it is advantageous for both parties, or it may lead to adverse selection. This adverse selection is linked to the fact that one of the contracting parties holds private information from which it can benefit because of the information asymmetry. In the postcontractual phase, a moral hazard problem sometimes arises, in other words agents may not respect their commitments. This can lead to the problem of free riding, which was mentioned in relation to the discussion on the work of Alchian and Demsetz [ALC 72].

The agency relationship thus generates agency costs in contrast with an ideal situation where there would be neither information asymmetry nor conflict of interest and thus an absence of costs. A comparison can be made between a reference situation, where a manager holds 100% of residual claims, and a situation where the owner opens his or her capital to external investors [JEN 76, p. 312]. In the first situation, the manager, who is supposed to maximize his utility, bears the totality of the consequences (monetary and non-monetary) of his choices. However, in the second situation, the manager is no longer the only one to hold the residual claims in the company. He then only bears a fraction of the costs associated with the consequences of decisions he makes to obtain non-monetary benefits. The investors, who are supposedly rational, anticipate the situation and propose a lower price than the intrinsic value of the title [JEN 76, p. 313; WIR 06]. This results in a loss of value that is rooted in the presence of agency costs related to the divergent interests of parties [JEN 76, p. 312; JEN 04, p. 21].

Agency costs can be broken down into three types of costs [JEN 76, p. 308, pp. 312–313]:

- – monitoring expenditures;

- – bonding expenditures;

- – residual loss.

The first two costs are explicit costs. Monitoring expenditures are costs that are incurred by the principal to induce the agent to act in the principal’s interest. This may involve the implementation of incentive or control systems, such as budget restrictions, operational rules or compensation policies. Bonding expenditures are linked to the self-discipline of agents. These are costs incurred by an agent in order to show the principal that if his actions go against his interests, he will be compensated. Residual loss are opportunity costs that arise from the fact that full protection of the principal’s interests, as guaranteed in an ideal situation and therefore in the absence of agency conflicts, cannot be ensured [JEN 76, p. 309]. They may be limited but cannot be entirely eliminated [JEN 76, p. 312].

In this context, value creation is achieved by minimizing all agency costs. This can be done through informal mechanisms, for example through trust, or formal mechanisms. In the latter case, the principal may put solutions in place to discipline the agent so that he acts in his interest.

Jensen and Meckling chose to illustrate their theory via agency costs that resulted from the relationship between shareholders and company management. However, their theory is not limited to this. Agency costs exist in any cooperative relationship. They do not necessarily require a subordinate relationship, as described by the principal–agent relationship [JEN 76, p. 309]. They can also arise in a dyadic relationship where both cooperation partners can simultaneously play the role of principal and agent, or in situations involving more than two actors. The different organizational structures are then justified if they are effective, in the sense that they make it possible to reduce conflicts of interest as much as possible, in other words, maintain the balance of interests.

The definition of strategic alliances, described so far as a cooperative relationship between at least two firms to achieve synergy effects due to joint production [ALC 72, p. 779], can therefore be supplemented. According to Jensen and Meckling [JEN 76], we can refine this description by stating that alliances constitute a dyadic relationship, where alliance partners both simultaneously play the role of principal and agent. This relationship is effective if it can reduce the losses in value that are associated with agency conflicts between contracting parties and the associated costs [JEN 76, p. 1992]. In light of our problem, of course, the question remains on the role of the presence of a PEF. This is discussed in the section on applying the theory to our research question (section 2.1.3).

Up to now, analyses have focused on relations between a company’s manager or management and its shareholders, and even between all of a company’s stakeholders. However, the PAT also allows agency relationships within the company itself to be considered. We then move from the field of governance to the field of organizational architecture.

2.1.1.2.4. The organizational architecture of a company

In defining a company as a nexus of contracts, its internal organization, i.e. its organizational architecture, can be defined as a set of contracts aimed at resolving conflicts resulting from the agency relationship and thus reducing the associated costs. These contracts are associated with three dimensions [JEN 92]: the allocation of decision-making rights, the evaluation of performance and the incentive systems to be designed such that they are all consistent.

The use of hierarchical coordination poses the problem of optimal allocation of decision-making rights between actors [JEN 92]. In order to allow good exploitation of knowledge, these are generally transferred to the agents that hold the specific knowledge [HAY 45]. This co-localization of specific knowledge and decision-making rights can be achieved in two ways: through the transfer of specific knowledge to the person holding the decision-making rights, or through the transfer of decision-making rights to the person holding the specific knowledge [JEN 92, p. 253]. The choice of allocation method depends on the transfer costs generated by the transfer of specific knowledge and decision-making rights [JEN 92, pp. 262–263]. However, the rights associated with the use of assets are generally not accompanied by the possibility of assigning those rights and appropriating the proceeds of that assignment [CHA 00, p. 199]. This lack of transferability means that agents are no longer encouraged to use their decision-making rights to act in the best interests of the organization [CHA 00, p. 199]. The delegation of decision-making rights then raises the problem of control of agents within the company [JEN 92, p. 251]. According to Fama and Jensen [FAM 83], delegation can then divide decision-making rights into two categories: rights related to decision-making and those related to control [JEN 92, p. 265]. The former include the initiative and implementation phases of a decision. The rights related to the control function include the ratification and monitoring phases [FAM 83, p. 303]. According to the theory of organizational architecture, the performance evaluation and the incentive system should be in line with the allocation of decision-making rights and in such a way that the costs of this arrangement do not exceed the efficiency gains.

2.1.2. Review of contractual theories

From a positive perspective, contractual theories include TCT and PAT. These are part of the efficiency paradigm. An organizational system (including the alliances we are interested in this study) is considered to be efficient if it maximizes the organizational rent (or surplus) and if there is no alternative mechanism to achieve, on average, better results for all stakeholders [MIL 92]. Within contractual theories, this efficiency is static in design. Agents are supposed to have limited computational rationality. This means that, when faced with a given set of opportunities known at an instant “t”, agents are supposed to be able to evaluate the consequences of their choices in probabilistic form but can commit computation or reasoning errors. Thus, we do not take into account a situation of radical uncertainty but rather a situation of weakened uncertainty, called risk, because it is possible to define this in probabilistic form.

Both theoretical frameworks seek to explain either the existence of a company or its internal configuration (its organizational architecture). According to the TCT, a company is justified because it makes it possible to reduce the costs that result from the imperfection of markets, which are characterized by the presence of information asymmetry, uncertainty and potential opportunism of actors. According to the Williamsonian analysis, hierarchical coordination (a company) can then reduce transaction costs in the presence of idiosyncratic assets and thus minimize value losses. According to the PAT, the unit of analysis is the agency relationship. This theory therefore makes it possible to consider the inside of a company, which was hitherto considered as a black box. Value creation is achieved by minimizing loss of value that results from agency costs due to conflicts of interest between the different agents involved in the transaction or in an agency relationship.

In both cases, a company is therefore efficient if, at a given moment, it can reduce losses in value as much as possible, thus getting as close as possible to the optimal situation in the absence of costs – also called the Nirvana economy [DEM 69] – or the first-order optimum (which is supposedly unachievable, meaning that one always strives for second-order optimum). The first-order optimum constitutes a reference situation or benchmark that cannot be reached, in theory [CHA 02b, pp. 19–20]. Ultimately, the focus is more on limiting value losses than on creating value [LAN 99, pp. 201–202]. Indeed, the question of the origin of given opportunities at a moment “t” is not asked. The whole point is to maximize the value created by acting on just one lever of action: the possibility of acting on the limitation of losses in value, linked to transaction and agency costs.

In Table 2.1, we list the key points.

Table 2.1. Contractual theories: key points

| Transaction cost theory | Positive agency theory | |

| Core authors |

|

|

| Angle and unit of analysis |

|

|

| Type of efficiency | Static | Static |

| Type of rationality of agents | Limited computational rationality | Limited computational rationality (REMM model) |

| Vision of the company | The company as:

|

The company in its capacity as:

|

| Handling of the environment |

|

|

| Central actors |

|

|

| Value creation |

|

|

| Key concepts |

|

|

2.1.3. Applying the theory to our research question

Staying in line with what has been presented on contractual theories in the previous sections, we begin by applying the theory of transaction costs to our problem (section 2.1.3.1) and following it up with PAT (section 2.1.3.2). In both cases, we begin our discussion from the perspective of an SME. The theories will help us, first, to identify the difficulties that companies supported by PE can encounter when forming alliances. Second, they will allow us to analyze the role that PEFs can play in solving the encountered problems. We will then turn to an analysis of the research question from the perspective of a PEF.

2.1.3.1. The role of PEFs in reducing transaction costs

We begin by looking at the role of PEFs through the TCT. According to the TCT, strategic alliances are defined as a hybrid mode of coordination, falling between the two extremes of market and firm (hierarchy) [WIL 91b]. So, what could the role of a PEF be in this perspective?

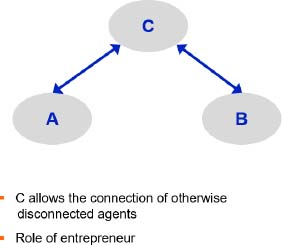

There are situations in which the implementation of governance systems by transaction partners may prove to be too costly relative to the potential gains. In such cases, the presence of a third party may be required. The role of the third party is then to be an arbitrator allowing contracts to be adapted more quickly than in its absence, which limits governance costs [WIL 79, pp. 249–250]. This may be the case if the involved asset or assets are moderately to highly specific, if the transaction is long term but occasional. Indeed, coordination costs in the presence of a specific asset are high and may not be covered when it is a non-recurring transaction. But, even in the case of recurring transactions, a third party can be useful.

Let us begin our discussion with a focus on SMEs (section 2.1.3.1.1) and follow it up with PEFs (section 2.1.3.1.2).

2.1.3.1.1. The SME perspective

PEFs typically invest in young, innovative, unlisted companies. As explained in the introduction to our problem, these companies present specific characteristics that will condition the role played by the PEF. We will therefore, first, detail these characteristics in the light of the TCT in order to explain the difficulties that these companies may encounter in forming alliances. This approach will then enable us to justify the presence of PEFs to overcome the problems encountered.

Difficulties encountered by companies supported by PE

Taking the effects of scale within transaction costs into account, Nooteboom [NOO 99, p. 20; NOO 93] argued that transaction costs increase in the presence of small unlisted firms compared to large firms. In light of the TCT, this can be explained in terms of information asymmetry, limited rationality, opportunism and uncertainty [NOO 93].

Information asymmetry

As presented in the introduction to our research question, due to their size and the fact that they are unlisted, small companies are not subject to the same disclosure constraints as listed and larger companies. This inevitably results in increased information asymmetry. The information asymmetry makes it difficult to assess these companies.

For alliance formation, this situation can generate additional costs, both for the company itself and for its future contracting partner. On the one hand, the detection of companies as future partners is more difficult and generates increased costs in terms of information research. On the other hand, this situation can induce costs for the company itself if it makes an effort to report or disclose information. Once detected, the examination and evaluation costs of these companies are generally higher due to the tacit nature of the knowledge and informal information.

Limited rationality

In small companies, the ability to process information is usually closely linked to the manager’s abilities. This also limits the scope for exploration and awareness of new possibilities for action. The problem in terms of intellectual capacity in information processing seems to be less significant for companies that are active in high-tech sectors, as the level of education of managers is assumed to be high. However, the lack of specialized internal staff (in finance, strategy, marketing, etc.) leads small businesses to resort to external experts. They build networks to obtain the necessary information. This networking is often informal and is costly in terms of seeking information and building relationships.

Opportunism

On the one hand, small companies are more vulnerable than larger firms to the potential opportunism of a contracting partner. On the other hand, large companies are more heavily subjected to the reputation mechanism, which reinforces the self-enforceability of contracts and thus reduces the risk of opportunism. This is due to the fact that the cost of cheating is higher if it is more likely that such a practice will be detected and the relevant information will be rapidly and widely disseminated. Large companies therefore seem to be more heavily subjected to this mechanism than small, unlisted companies. Building or maintaining reputation capital is more difficult and costly for a small, non-established company. As the markets in which small companies operate are less efficient, their information is disseminated more slowly and to a smaller audience than that of listed companies. Small businesses therefore have to make a greater effort when meeting with future partners to establish a situation of trust that will make their commitments trustworthy. This generates costs.

Uncertainty

Uncertainty only accentuates the contractual problems that we have mentioned so far [WIL 79, p. 254]. As defined by Knight [KNI 21, part I, Chapter I], it makes it impossible to model the various states of the world in probabilistic form. Companies financed by PE are typically active in high-tech sectors. These sectors are characterized by a high degree of uncertainty, which makes it even more difficult to draft contracts, so these therefore remain incomplete. The incompleteness of contracts and their informal nature are increasing in areas where the exchange of information and knowledge is important, such as R&D and marketing. Cooperation between companies in such areas gives rise to the creation of assets that are idiosyncratic to the transaction. They are the result of investments in human or physical capital that are specific to the transaction and which make it possible to achieve a rent if the contracts are executed correctly [WIL 79, pp. 240–241]. Investments in both intangible assets and human capital accentuate the effects and consequences of idiosyncratic investments [WIL 79, p. 242].

In summary, from a TCT analysis perspective, young, innovative and unlisted companies have certain specific features compared to large companies. These particularities are essentially linked to a more pronounced information asymmetry, a higher limited rationality and a strong uncertainty about the environment. Moreover, they appear to be less reliable ex ante than a large company with established reputation capital.

These features increase the transaction costs associated with seeking out information about potential transaction partners, evaluating them and setting up contracts. Contracts are essentially incomplete and informal in nature and controlling them ex post is also more costly. The formation of alliances in the precontractual phase is therefore more costly than for a large company, which can lead to the failure of such a transaction.

To ensure that the transaction does not fail, mechanisms must be put in place ex ante to reduce information asymmetry and set up guarantees or solutions that ensure the credibility of commitments and establish a situation of trust. Ex post contracts require a flexible mechanism so that they can be adapted [WIL 79, p. 242]. Because of this incompleteness of contracts, trilateral governance is then even more important, meaning a third actor playing the role of arbitrator [KRE 98, p. 133]. This is more effective than detailed contracts. Do PEFs reduce ex ante transaction costs that can prevent alliance formation? Ex post, can they assume the role of an arbitrator?

The role of PEFs in solving the problems encountered

Let us discuss if PEFs can reduce ex ante transaction costs, which can prevent the formation of an alliance and ensure an ex post arbitration role.

In our case, PEFs seem particularly well “predisposed” to limit transaction costs and act as arbitrators. Indeed, they are capable of reducing the information asymmetry that can explain, ex ante, why at least one of the future partners in the alliance gives up on forming the alliance. PEFs are able to produce the missing information at lower costs than the companies themselves (or potential alliance partners) because they already collect the necessary information for their own decision-making [JEN 76, p. 338]. Since they support the companies in question, usually they will have carefully analyzed the files before selecting a candidate for financing. In addition, their presence on the board of directors gives them direct access to information, particularly that of a strategic nature. They can thus facilitate the exchange of information and beliefs by monitoring information flows [HSU 06, pp. 206–207; LIN 08; GOM 09, p. 2]. PEFs are therefore able, ex ante, to reduce information asymmetry and thus increase the credibility of commitments, which limits transaction costs.

Ex post, PEFs can continue to play a favorable role in reducing the information asymmetry. They can also coordinate, if necessary, the actions of alliance partners and intervene in the event of conflicts. This last potential PEF intervention will be discussed in the section on applying the PAT to our research question. Before this, let us consider the perspective of PEFs.

2.1.3.1.2. The PEF perspective

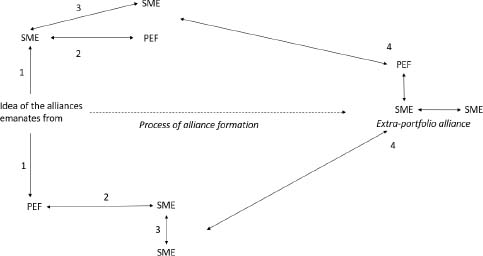

Let us now turn to the point of view of PEFs. In the previous section, we argued that PEFs are able to reduce transaction costs that may prevent alliance formation and they can act as an arbitrator. But are these costs not borne by the PEFs? We distinguish between the cases of an intraportfolio alliance (formed within the investment portfolio of a PEF) and an extraportfolio alliance (formed between a company supported by PE and a company that is external to the investment portfolio of the PEF).

Intraportfolio alliances

From the perspective of a PEF, the costs associated with reducing the information asymmetry should be relatively low. As previously mentioned, the PEF collects a certain amount of information during its analysis of prospects for financing. Once a candidate has been chosen, they are regularly kept informed by the managers of the supported SMEs on the essential points. In addition, they usually sit on the board of directors or similar boards (strategic boards, etc.), which gives them access to information of a strategic nature.

Of course, PEFs are obliged to keep the information they have about their portfolio companies confidential. The provision of such information would in any case be unnecessary. It is sufficient for the contractor to know that there is a PEF involved in the capital of the future alliance partner to establish a certain level of trust. A contractor would know that PEFs carry out meticulous analyses before they invest in a company and that they require subsequent reports. This is all the more true if all of the companies in an alliance share a same PEF. The PEF is then a common actor that all of the partners are familiar with. Companies therefore know from experience what information PEFs have access to.

These conclusions are especially applicable to the formation of intraportfolio alliances, in other words alliances formed between companies supported by the same PEF. The question then arises as to whether this also applies to extraportfolio alliances, which include at least one company supported by PE and one company outside of the PEF’s investment portfolio.

Extraportfolio alliances

We propose distinguishing between two specific cases. In the first case, the company outside of the PEF’s investment portfolio is either a former PE-backed firm or a prospect that the PEF has analyzed but with which the PEF or the company renounced any cooperation. In this case, the PEF is aware of the company’s file and has had access to certain information about it. The argument can then be referred to the case of intraportfolio alliances.

In the second case, the company outside of the PEF’s investment portfolio is not known by the latter. In principle, the PEF has no informational advantage. Does this mean that the PEF cannot act as a mechanism to reduce transaction costs? We do not believe so. The fact remains that one of the companies is supported by PE. For the company outside of the PEF’s investment portfolio, this may reinforce the confidence it has in the SME supported by PE, because the presence of a PEF is a sign of the company’s quality compared to if it did not have this support. The company supported by PE has a strategic advisor with whom it discusses such steps and with whom it can seek advice. These different elements can reinforce an impression of quality and seriousness of companies and thus reduce the rapprochement costs for both companies.

The TCT makes it possible to highlight an initial role that a PEF could play in strategic alliances. In order to better study this relationship, let us use the PAT next. This will allow us to focus on the agency relationship, whereas the TCT uses the transaction as the unit of analysis. We can thus take into account potential conflicts of interest between contracting parties since the analysis allows the contracting parties’ preferences or attitudes toward the transaction to be explicitly taken into account.

2.1.3.2. The role of PEFs in reducing agency costs

Since the PAT focuses on agency relationships between two or more actors, it allows us to focus on the agency relationship that PEFs have in strategic alliances. According to the PAT, strategic alliances are a cooperative relationship between two or more companies. This cooperation makes it possible to achieve synergy effects due to collaborative production [ALC 72, p. 779]. It is effective at a given point in time if it can reduce the losses in value associated with agency conflicts between contracting parties and the associated costs [JEN 76; JEN 92].

Agency conflicts arise because of differences in interest between the contracting parties and they usually arise in the postcontractual phase, and therefore, in our case, after the formation of the alliance. However, potential differences of interests with the parties linked to the relationship may also pose problems in the precontractual phase, ex ante to the formation of the alliance.

In section 2.1.3.2.1, we discuss conflicts of interest in the precontractual phase and the solutions that PEFs can provide. Then, we proceed in the same way for the postcontractual phase (section 2.1.3.2.2). Although we are more interested in the formation of the alliance and not its life span, the anticipation of conflicts that may arise once the alliance has been formed can have the consequence, ex ante, that one of the potential partners refuses the cooperation. The alliance cannot then be formed. In a third point, we consider the possible interweaving of different governance mechanisms (section 2.1.3.2.3). Indeed, the presence of other mechanisms may weaken the respective weight of PEFs as a governance mechanism and thus their role in strategic alliances.

2.1.3.2.1. The role of PEFs in the precontractual phase

As before, let us begin our discussion from an SME perspective before continuing with the PEF perspective.

The SME perspective

Let us first consider the relationship between two companies that are backed by a PEF and that are forming an alliance, without taking the PEF into account. This will enable us to analyze the difficulties that this type of company may face in forming an alliance and to discuss, in a second step, the solutions that the PEF can provide.

Analysis of potential conflicts of interest between SMEs

Within the agency theory, actors are supposed to decide rationally – that is, they seek to maximize their own utility – and decide by evaluating the consequences of their choices. This computational rationality is however limited, as in the TCT. Individuals cannot predict everything and they make mistakes. As the information asymmetry is strong in the presence of young unlisted companies that are evolving in an innovative environment, agency conflicts linked to diverging interests are presumed to be likely.

The precontractual risk that arises in light of our problem is that a mutually advantageous alliance cannot be achieved. Because of the information asymmetry, it is possible that one party holds private information on the subject of the transaction and seeks to profit from it to the detriment of the other contracting party. The possibility of such behavior is sufficient to generate distrust of the future partner [BRO 93, pp. 13–15]. Since the relationship between the two companies forming the alliance can be considered to be dyadic, this risk of adverse selection arises simultaneously for both parties (for example [TEE 86]). In addition to these potential conflicts, given that PE-backed companies are in the precarious stages of their lifecycle and they operate in sectors with high uncertainty and often do not yet have any track record, potential partners may not join forces, first, because of doubts about their quality. Second, potential partners may refuse to cooperate with them for fear of possible financial instability [BAN 08].

As information asymmetry is at the root of potential conflicts, it must be minimized in order to avoid failure of the transaction. A classic solution to this problem is to insure against this risk on a contractual basis [ALC 78, pp. 302–307]. Depending on the design of the contract (for example the guarantees required), the contracting parties may need to disclose some information. Companies are sometimes led to send out signals that give credibility to their commitments. These signals are only credible if it is not possible to replicate them without bearing high costs. In the case of an alliance formation between young companies at the start of their activity and operating in an innovative sector, it is assumed that the investments of both parties linked to the transaction are mainly investments in human assets. Guarantees to give credibility to the parties’ commitments may be, for example, patents concerning know-how or diplomas guaranteeing the qualifications of the workforce [AKE 70, p. 494]. The request for guarantees and the issuing of signals by the contracting parties give rise to monitoring and bonding costs, respectively.

However, this solution presupposes the existence of appropriately formalized information. But, since PE-backed companies are often in the early stages of their lifecycles and operate in innovative sectors, their knowledge is usually quite tacit, and the information is rarely formalized. This complicates the situation, since commitments that are not based on written documents make it difficult to enforce contracts before the courts. Thus, they do not make the commitments credible. Formalizing the information can then be too costly, if not impossible, for these companies in the face of potential gains linked to the cooperation, which can lead to the failure of the transaction.

In the presence of informal contracts, mechanisms that facilitate the self-execution of contracts and thus reduce agency costs are therefore the solution. One example of such a mechanism is trust [AKE 70]. It facilitates investment in specific human capital, in particular by reducing the risk of adverse selection. This mechanism is important, especially since joint investment in human assets generates large flows of knowledge, which increases the risk of companies losing their own know-how [ALC 78, pp. 313–319].

However, trust is a bilateral mechanism [CHA 90]. It can only be established through the interaction of two agents, which requires either some time for it to develop or an ex ante guarantee. If the future contracting parties do not know each other before the transaction, a mechanism for establishing a situation of trust in the precontractual phase may be reputation. The latter is a complementary and necessary mechanism for the trust mechanism to work [CHA 90]. Reputation itself is only an effective mechanism if there is a high probability of detecting uncooperative behavior and if information about uncooperative behavior is disseminated quickly and widely. Reputation thus includes a shared dimension between several actors. However, when companies are young and unlisted, their reputation capital can be assumed to be low. The ex ante efforts made by these companies to demonstrate to their environment that they are reliable generate bonding costs that may exceed the anticipated gains from the relationship. The precontractual problem therefore remains.

This situation arises for SMEs that wish to form an alliance, whether it be an alliance formed within the portfolio of a PEF (intraportfolio alliance) or one including a company that is external to the PEF portfolio (extraportfolio alliance). However, the two cases are not similar with respect to potential PEF intervention. This is what we will discuss in the next point.

Solutions that PEFs can provide

Faced with this precontractual problem, we now seek to discuss the role that PEFs can play. As mentioned before, PEFs can reduce asymmetry and, consequently, transaction costs. Since information asymmetry is also the source of problems that cause agency costs, PEFs can also reduce then. They act as a mechanism to establish the necessary trust in the presence of informal and incomplete contracts and thereby give credibility to the long-term commitments of companies. But how do they do this? Once again, we distinguish between the two cases of intra- and extraportfolio alliance formation.

- A) Intraportfolio alliances

Let us begin with an alliance formed within the investment portfolio of a PEF (intraportfolio alliance). The PEF therefore supports both companies wishing to form the alliance. It can then act as a mechanism for building trust. But how does it do this?

First, since PEFs scrutinize the companies they support, this allows a relationship of trust to be established between the companies and the PEFs. The relationship they have with the companies they support serves as a basis for building mutual trust. This vertical trust between a PEF and the companies it finances can then serve as a basis for building horizontal trust between the two companies during the precontractual phase in the formation of a strategic alliance [AKE 70, p. 497; KRE 98, p. 133; CHU 00, p. 7]. Second, as PEFs are involved with several players and are usually listed, bad behavior on their part could be directly sanctioned. PEFs also have reputation capital to defend, which strengthens the trust mechanism. Because of their role as a trust mechanism, they reinforce the self-execution of contracts, which limits agency and transaction costs.

In the case of an alliance involving a company outside the PEF’s investment portfolio (extraportfolio alliance), the PEF can also play the role of a trust-building mechanism. However, in this case, the way in which it intervenes is slightly different.

- B) Extraportfolio alliances

Let us now consider the case of an extraportfolio alliance. Again, there are two scenarios. In the first case, the company external to the PEF’s investment portfolio is either a former portfolio company of the PEF, or a prospect that the PEF has previously considered but ultimately the PEF did not support. As before, our argument in this case refers to that of the intraportfolio alliance. In the second scenario, in principle, the PEF does not know about the company outside of its investment portfolio and vice versa. Unlike in the previous situation, however, the company outside of the PEF’s investment portfolio did not establish any prior relationship of trust either with its future alliance partner or with the PEF. As SMEs supported by PE are often, as already mentioned, at a precarious stage of their lifecycle, operating in highly uncertain sectors and often not yet having any historical performance to present, a potential partner that is external to the PEF’s portfolio may doubt its financial stability as well as its quality and may decide not to join forces. But does a PEF reduce these concerns?

Regarding the fear of financial instability, the presence of a PEF in the case of an extraportfolio alliance does have an effect. Mistrust toward the quality of a future partner leads parties to demand guarantees. A PEF, simply by its presence, can then play the role of “guarantor” and “certify” the financial stability of the SMEs it supports. If the latter face liquidity problems, PEFs are able to support them financially. This role seems all the more important given a PEF’s reputation on the markets. It should be noted that the terms “guarantor” and “certify” have been placed in quotation marks – these do not explicitly mean that PEFs formally guarantee or certify the financial stability of the companies they support. Rather, their mere presence in the SME’s capital allows them to play this role informally. Their presence, as well as their status as an investment company, helps to allay the mistrust of future partners and even to establish trust, compared to if there were no PEF at all.

Concerning the distrust of external companies toward the quality of an SME supported by PE, when it comes to associating within an alliance, a PEF can play a role in terms of certification of the quality of the supported companies. As one PEF in the United States stated in a 2006 press release: “Venture capitalists place a high value on strategic alliances and joint ventures as they provide an opportunity to demonstrate the validity of the science and its commercial potential” [MIT 06, p. 2]. In order to select the candidates they will support, PEFs undertake due diligence and assess, among other things, the specific knowledge, skills and resources of companies. They are able to identify and evaluate the know-how of SMEs, since they are specialized in these fields and provide the necessary skills. PEFs can then strengthen the credibility of these SMEs’ commitments to future alliance partners. They build trust through their expertise and reputation capital, which PE-backed companies could not do alone or at least not without incurring considerable costs.

In connection with the arguments we put forward, Megginson and Weiss [MEG 91], Stuart et al. [STU 99, p. 315], Hsu [HSU 04, pp. 1805–1806] and Nahata [NAH 08, p. 127] pointed out that when the quality of a young SME cannot be directly estimated, external actors rely on the quality of the actors that operate with the latter to assess its quality. As a PEF has more visibility and notoriety than the supported SME, it can then constitute such an actor. Indeed, in line with these ideas, Hsu [HSU 06; HSU 04] believes that PEFs can play a role in certifying the quality of the portfolio companies. In his 2004 article [HSU 04], he argued that the field of PE presents a near-ideal affiliation market with renowned agents for young SMEs. These companies are willing to accept a lower amount of liquidity in exchange for a percentage of their capital, if they value the certification role of the PEF [HSU 04, p. 1807; ALE 10]. Based on these results, in 2006 [HSU 06] he wrote that the presence of a PEF has a positive impact on the formation of cooperation between biotechnological SMEs that it backs, as well as on their likelihood of going public. Such cooperation takes the form of strategic alliances or licensing agreements. In addition, he shows that PEFs differ according to their reputation and that the latter has a favorable impact on both the cooperation activities of SMEs and their probability of going public. We can conclude that in the case of an alliance that includes a firm that is external to the PEF’s investment portfolio, the reputation of the PEF may play a favorable role in the establishment of trust.

The developments in this and previous sections lead us to propose the following hypothesis: the reputation capital of PEFs strengthens the trust mechanism, which makes it possible to reduce transaction costs (argumentation referring to the TCT) and agency costs (argumentation referring to the PAT), which has a positive impact on the formation of alliances for supported companies.

HYPOTHESIS 1.– All else being equal, the reputation capital of PEFs strengthens the trust mechanism and, therefore, has a positive impact on the formation of alliances for the companies they support.

The PEF perspective

So far, the issue has been presented from the point of view of SMEs. The question therefore remains about the interests and perspective of the PEF in the formation of alliances in the phase preceding their formation. In general, the interests of PEFs depend on their position in their lifecycle and the structure of their own investors.

According to Ozmel et al. [OZM 13], a PEF may have an interest in forming alliances between the companies it supports if its own reputation capital is weak. They studied the extent to which PEFs and alliance formation are complementary or substitutable mechanisms in the decisions of companies to go public as well as their impact on the probability of an exit via acquisition by another company or another PEF. In the case of an initial public offering (IPO), they found that the probability increases if the PE-backed SME forms an alliance. The PEF and the alliance are complementary mechanisms in this case. Nevertheless, this complementarity tends to become a substitution effect as the number of alliances formed increases.

Let us apply this reasoning to our own argument. In line with the developments in the previous section, a PEF plays a role in certifying the quality of the SME it supports if it has a certain reputation capital. This is built progressively through accumulation of experience and performance [SHA 83; HSU 04, p. 1807]. It can therefore be assumed that the younger a PEF is, the lower its reputation capital will be. In which case, it must build it. A faster way to achieve this reputation capital if it does not have enough, is to link its portfolio company with established partners, for example through a strategic alliance. Cooperation within an alliance with a partner with reputation capital or contact with other reputable agents can be either a complementary mechanism [CHA 04; OZM 13] (if the PEF has reputation capital but it is weak) or a substitute (if the PEF does not yet have reputation capital) for the role played by reputable PEFs. These developments lead to the following hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 2.– All else being equal, for a PEF with a low reputation capital, the formation of alliances for its portfolio companies with partners that have reputation capital constitutes a mechanism that is complementary to or even substitutable for the role of certification played by well-reputed PEFs.

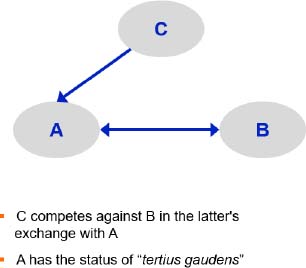

Beyond the needs of PEFs according to the stage of their lifecycle, their interests will mainly depend on their own investors (the State, a region, private investors, a PEF owned by a company, etc.) as well as their purpose (focus on investments in certain sectors or regions, etc.). On the one hand, PEFs seek to make investments of their capital providers profitable. In connection with the objective of seeking rents, Kamath and Yan [KAM 10] pointed out that the presence of a PEF can have a negative effect during transactions between SMEs. They analyzed acquisitions between companies financed by PE and showed that PEFs can take advantage of their intermediary position by using their informational advantage to try to extract rents. On the other hand, it can be assumed that the interests of PEFs in forming alliances may differ depending on the nature of their ownership structure. Therefore, favorable effects can be expected if the State, a region or a competitiveness cluster are present in the capital of the PEF and they wish to promote regional development in general or in certain sectors. The influence of shareholders on the decision-making of PEFs, particularly in the formation of alliances, may be assumed to be greater if the PEF takes the form of a JSC with or without VC status, compared to if it takes the form of a VCMF. As presented in our introduction, PEFs in the form of VCMFs differ from those in the form of VCs in that investment decisions can be taken completely independently of the fund’s subscribers. Only venture capital funds with an investment committee are an exception to this rule if the committee consists of the fund’s main subscribers. The independence of the investment decisions undertaken by the management company may then be called into question.

In France, some PEFs are involved in schemes that are designed to promote the development of regional and/or sectoral activities and finance projects that structure Competitiveness Clusters (for example OSEO and the Fonds d’investissement stratégique). The objective of the clusters is to bring together companies, research laboratories and educational institutions within a given territory to develop synergies, cooperation and partnerships. We propose the following hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 3.– All else being equal, the presence of the State or a region in the capital of a PEF, or its involvement in a competitiveness cluster, positively affects the formation of alliances for companies supported by the PEF.

2.1.3.2.2. The role of PEFs in the postcontractual phase

Beyond the problem of adverse selection, potential partners may fear uncooperative behavior by the other party in the alliance once the alliance is formed. Although we are mainly interested in the role of PEFs in the formation of an alliance and not throughout the life span of the alliance, we must consider potential conflicts of interest after the formation of the alliance because their anticipation can lead, ex ante, to potential partners renouncing the alliance.

Information asymmetry makes it costly, if not impossible, to observe the other party’s behavior. The parties involved in a transaction may seek to take advantage of the situation. By taking advantage of the work provided by their partner (“free-riding”), they alone appropriate all of the gains from their behavior, while the related costs (a reduction in production) are borne by both parties [ALC 72, p. 780].

In light of our problem, there are two main agency relationships. The first is between two companies within an alliance, which we consider to be dyadic and bilateral in nature. This relationship is discussed in the section where we analyze the problem from the point of view of SMEs. The second main relationship, and the one that is of particular interest to us, is the agency relationship between the PEF and the alliance. This is further explored in the section on the PEF perspective. We distinguish, as we have done throughout this book so far, the relationship between companies that form an intraportfolio alliance and the relationship between companies that form an extraportfolio alliance, if this is relevant.

The SME perspective

To consider our problem from the point of view of SMEs, we break it down into three points. First, we discuss the different sources of conflict of interest. Then, we present the agency relationship between the SMEs that form the alliance based on these different sources of conflict. Finally, we present the solutions that PEFs can provide.

Different sources of conflicts of interest

Let us now turn to an analysis of potential conflicts of interest between actors. To do this, we must take the utility functions of the parties into account. Although the behavior of all actors cannot be accurately predicted, it is possible to make assumptions about their “typical” or “average” behavior. There are various reasons for conflicts of interest. By summarizing the models used in the literature on agency theory, the following sources could be identified:

- – the choice of level of effort that is a source of disutility for the manager or the consumption of non-monetary benefits by the manager, which opposes the interests of shareholders (for example [JEN 76, p. 312; JEN 86; BAL 03]);

- – different behavior due to different time horizons or costs of capital (for example [ROG 97; REI 97]);

- – differences in risk exposure: investors can be considered to have better access to financial markets than managers and, as a result, have better means of diversification. Consequently, assuming that individuals are risk averse, the premium asked by the manager should be higher than that called for by shareholders. In models, for reasons of simplicity, shareholders are generally considered to be risk neutral, whereas managers are assumed to be risk averse (for example [FEL 99]);

- – the problem of discretionary space and entrenchment.

This literature usually focuses on the agency relationship between shareholders and managers. The results therefore cannot be transposed to our problem, but they can serve as a “checklist” concerning potential sources of conflict.

Let us begin our analysis with potential conflicts of interest between two companies forming an alliance. First, we ignore the presence of the PEF. This will allow us to highlight any difficulties encountered by SMEs and, in a second step, to focus on the solutions that a PEF can provide.

The agency relationship between SMEs forming an alliance

The relationship between two companies forming an alliance is assumed to be dyadic in nature. Both companies thus simultaneously play the role of the principal, delegating the task to the agent, and the role of the agent who is delegated a task. The dyadic nature of the relationship, as we see it, does not mean that SMEs necessarily have the same weight in the alliance relationship. If one considers, for example, the particular case where an alliance takes the form of a joint venture, the percentage of capital held by the joint-venture companies is not necessarily identical. Nevertheless, a bilateral alliance is a collective effort. Like any group work, cooperation through an alliance encourages the transaction parties to take advantage of the partner’s work and appropriate a share of the rent. The problem is therefore about the choice of level of effort that one of the two companies puts in once the alliance has been concluded. Such behavior, known as free riding, is inherent in all group work [ALC 72, pp. 779–780].

This situation seems to become more prominent the more tactic and informal the purpose of the alliance is, and when the partners’ contribution is difficult to assess. This may occur if the alliance essentially involves the transfer of specific knowledge from one partner to another or if the alliance project is essentially based on the joint development of new knowledge. For young innovative companies, the specific knowledge they hold and can bring to the cooperative relationship within an alliance is often their key asset. However, their evaluation and protection require professional expertise that these companies often do not possess. Due to the tacit and informal nature of knowledge, the effort that one of the parties undertakes to enable the transfer of specific knowledge is difficult to assess. Similarly, when jointly developing new knowledge, it can be difficult to measure the involvement and quality of the effort made by each actor.