7

Seven Fat Years, or Illusion?

As promised at the beginning of this book, we will draw some conclusions about the success or failure of the conservative economic policies of 1979–90. To do this, we will first identify the various arguments that have been raised in support of the view that the Volcker-Reagan regime was successful. Then we will catalog the various arguments in opposition. Only after we have explained the arguments as coherently as possible will we be able to figure out which pieces of evidence are useful in refereeing among them.

The Conservatives Celebrate Reagan’s Revolution

In 1992, with the election campaign being fought as a partial referendum on the economic policies of the 1980s, Robert Bartley of the Wall Street Journal and the magazine National Review both produced major efforts to restate the successes of the Reagan economic policy. Bartley’s was a full-length book called The Seven Fat Years and How to Do It Again. The National Review produced a series of articles called “The Real Reagan Record.”1 In addition to these sources, the various reports of the Council of Economic Advisers throughout the Reagan and Bush administrations provide evidence and arguments for the successes of the Reagan economic policies.

Interestingly enough, the centerpiece of most of the analysis by the Council of Economic Advisers is the successful battle against inflation, while Bartley and the National Review focus on economic growth, productivity growth, and job creation. For starters, we note that inflation was significantly reduced and from 1983 on never exceeded 5 percent. The low rate did not stop the Federal Reserve from remaining extremely vigilant, even indicating in the late 1980s that zero inflation was a realistic goal. Once we recognize the success with inflation, we can turn our attention to the other macroeconomic impacts: investment, productivity growth, income growth, and job creation.

As mentioned in chapter 2, investment plays an important role because it is at the same time a stimulator of aggregate demand and the vehicle by which productivity increases find their way into the economy. Let us consider the most mundane of technological improvements, the substitution of the scanner at the supermarket checkout line for the eyesight, recognition, and digital dexterity of the clerk. It may not seem like much, but it takes a clerk perhaps three times as long to locate the price on an item and punch it into a cash register as it does to run the universal product code past the scanner. Thus, people wait shorter times at checkout counters and stores need fewer clerks to process the same number of people. Introducing scanners is clearly an example of an improvement in productivity.

But those scanners would not be at the checkout counter if some company had not invested in the equipment to make them and the supermarkets had not made investments to buy them. The actual fixing of new technology in new products and then integrating that new technology into an already existing production process requires investment.

If we then move to the world of information processing—clerical work and record-keeping—we note that the replacement of the typewriter and carbons by the computer and xerox machine that revolutionized the office in the 1970s and 1980s required massive investments. First the computer companies produced the hardware and software. Then the businesses bought them for their offices. Both of these demanded a great deal of thinking, figuring, learning, and adapting, but they also involved physical creation of new equipment.

So investment is a major indicator of the private sector’s activity that does two positive things at once. On the one hand, it provides a kick of aggregate demand that, via the multiplier, induces consumption and raises GDP. On the other hand, it potentially increases society’s productivity because investment involves adding new capacity and replacing old capacity. The best way to measure the impact of investment on an economy is to look at investment as a percentage of GDP. When investment rises faster than GDP (in other words, when investment as a percentage of GDP increases), it is playing a significantly stimulative role. Over a business cycle upswing, one can track the contribution of investment to increases in productivity by noting the average ratio of investment to GDP. Here, historical comparisons to other business cycle upswings are useful. Even though the relationship between investment and productivity is an uncertain one, the point is that investment at least provides a potential for improvement in productivity. Measuring investment as a percentage of GDP becomes a useful indicator of how well changes in the incentive structure (say, as a result of tax changes, regulatory relief, and the overall improvement of the business climate) have worked.

For Bartley and others, the level of investment in the 1983–90 period is not the only story. Equally important is the rise of the venture capital industry. The great computer-driven transformation of communications, information processing, home entertainment, retailing, and so on involved new products and new companies. Before these new companies are actually out soliciting investors, they are nothing but ideas in the minds of dreamers. Would-be entrepreneurs need start-up capital to transform their ideas into tangible assets so they can take the next step, product development. If they do not already possess this start-up capital, as is usually the case, they need to interest lenders who are willing to take risks for the sake of high potential payoffs. Bartley points out that

the sale of shares, or IPO for initial public offering, is a latish stage in the capital investment process. . . . The most crucial seed money comes earlier. For this, U.S. capitalism has developed an industry. . . . Venture capital firms raise money on the bet that their management can pick out the most promising new firms, provide the initial funding and produce extraordinary returns.2

Bartley explains the availability of venture capital that provided the initial money for the technological transformation of much of American industry and society during the 1980s as resulting from the capital-gains tax cut of 1978, followed by the successful retention of the capital-gains preference in the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981.

The availability of financial capital has been the subject of tremendous controversy. Many have criticized the focus on purely financial investment as opposed to real physical investment that actually improves the productivity of the economy and puts people to work. From the point of view of an individual deciding what to do with one hundred thousand dollars, it makes no difference whether she or he buys a life insurance policy, stock, or bonds or starts a business. The key decision will depend on the expected rate of return corrected for risk. However, the first three examples merely move the savings from control of the individual to control of the insurance company or from seller of the stock or the bond to the purchaser. No investment that affects GDP has occurred. Starting one’s business, assuming it involves purchasing capital equipment and perhaps even some construction activity (retrofitting a building, for example), does physically increase the nation’s capital stock. If the business starts up with the newest technology, the start-up investment is making a contribution to increasing society’s productivity.

There was a significant acceleration in the amount of purely financial investment, specifically merger activity, during the 1980s.

[M]ergers and acquisitions increased from 10,108 during 1979–83 (an average of 2,022 per year) to 18,389 during 1984–88 (an average of 3,678 per year). . . . the total value of mergers and acquisitions increased from $249.9 billion during the first five years of this period to $880.3 billion during the last five years.3

Such purely financial investment has the potential to increase society’s productivity, but only indirectly. Getting the savings of millions of individuals into the hands of risk-taking entrepreneurs make new investments possible. Bartley and others have argued that even the financing of takeovers, often accompanied by struggles over the terms merging two giants, have created the fear of outside acquisition and have forced companies, in the words of Fortune, to “cut fat, restructure, and become more efficient.”4 And in fact, employment in Fortune’s top 500 corporations fell 3.5 million between 1980 and 1990. Nearly half the companies listed in 1980 were not listed in 1990: “Most of the missing had been merged with other companies.”5 The Council of Economic Advisers in their 1985 report devoted an entire chapter to the market for corporate securities and concluded that on balance the growth of purely financial investment, especially mergers and acquisition, had been good for the productivity of the businesses involved, because only the threat of an outside-takeover bid forced a management to be highly responsive to the needs of their shareholders.6

Another element in the argument that the Reagan years were a solution to the problems of the 1970s involves emphasizing the successes after 1982 and contrasting that with the period between 1973 and 1981. Thus, the 1989 report by the Council of Economic Advisers stated,

Between 1973 and 1981, the rate of inflation was nearly three times as high as between 1948 and 1973, averaging more than 8 percent and reaching 9.17 percent . . . at the business cycle peak in 1981. . . . Higher inflation was not buying lower unemployment, and the unemployment rate reached 7.4 percent at the business cycle peak in 1981. . . . Productivity growth plunged to a scant 0.6 percent per year between 1973 and 1981. . . . Growth in real GNP per capita was cut to one-half the 1948–73 rate, to a 1.1 percent annual rate between 1973 and 1981. Real median family income showed no growth, despite the growth in the proportion of two-earner families. . . . The poverty rate increased from 11.1 in 1973 to 14.0 in 1981.7

By comparison, the council emphasized the successes of the 1980s.

Since 1981, real GNP has risen at a 3.0 percent annual rate, a significant improvement over the 2.1 percent annual rate between 1973 and 1981. Real GNP per capita has risen at a 2.0 percent annual rate, compared with a 1.1 percent annual rate between 1973 and 1981. . . . Since 1981 private business sector productivity has grown at a 1.7 percent annual rate, more than double the 1973–81 rate. Manufacturing productivity has grown at a 4.1 percent rate since 1981, roughly one and one-half times the postwar average and more than three times the rate of 1973–81.8

Finally, the council argued that gross investment was above the postwar average as a percentage of total output, but that the net investment had been trending downward.9 This is an important point. In the National Income and Product Accounts of the United States, gross investment includes a measure of the economic cost of replacing worn-out capital equipment.10 That cost has been rising as a percentage of GDP for the last twenty years. From our point of view, gross investment is the appropriate measure, because even investment that replaces worn-out equipment incorporates the latest versions of that equipment, increasing productivity. Despite the low level of net investment, the productivity of the nation’s capital stock was rising, contributing, according to the council, to the positive overall productivity performance of the economy.

The Mainstream Critique

Two elements usually surface in the mainstream critique of the 1983–90 period. The first and most dramatic is the so-called twin-deficits problem. The argument goes like this. When the recovery of 1983 began in earnest, the fiscal-policy changes had become so entrenched that the structural deficit was a very high percentage of GDP. Thus, as the economy began to show signs of a vigorous recovery in the second half of 1983 and all of 1984,11 the federal deficit as a percentage of GDP rose. It was 4.9 percent in the fiscal 1984 and 5.2 percent in fiscal 1985.12

This led the Federal Reserve to tighten up on monetary policy. After falling steadily from April 1982 to February 1983 (from 14.94 percent to 8.51 percent) the Federal Funds rate climbed to 11.64 percent in August 1984 before falling back to 8.35 percent in January 1985. The entire average for 1984 was 10.23 percent. For 1985 it was 8.10 percent. This tight-money policy stopped the recovery of 1984 short of reducing the unemployment rate anywhere near the so-called natural rate of 6 percent. The unemployment rate fell to 7.3 percent in the fourth quarter of 1984 and stayed at 7 percent or higher until the fourth quarter of 1986, when it finally reached 6.8 percent. It didn’t fall below 6 percent until the fourth quarter of 1987. Similarly, the capacity utilization rate rose from its nadir of 72.4 percent in the fourth quarter of 1982 to 81.8 percent in the third quarter of 1984. It fell to 78.7 percent in the third quarter of 1986 before rising to its maximum of 84.6 percent in the first quarter of 1989.13

The tight-money policy worked to counter the strong fiscal stimulus of the structural deficit during 1984 and 1985. As a result inflation was not rekindled by the recovery, but from the point of view of fully utilizing human and physical capacity, the economy stalled far short of its potential GDP. Thus, for mainstream economists at least part of the explanation for the success of the anti-inflation policy was the maintenance of a high level of unemployment and a low level of capacity utilization.

In addition, some economists in the mainstream tradition have been anxious to note that the rise of international competition during the late 1970s and especially the 1980s has made it virtually impossible for noncompetitive firms to raise prices in the face of declining demand. This argument suggests that it was not the Volcker-Reagan policy that defeated inflation but increased international competition. Many also believe that the success of the Volcker anti-inflation program was based in part on a “supply shock” of falling international oil prices after 1981. Just as many economists argued that the difficulties in the 1970s could be explained with reference to upward surges in oil prices, these same economists believed that the 1983–89 recovery’s proceeding without rekindling inflation had more to do with the fall in oil prices than with the policies of the Federal Reserve.

The method by which inflation was reduced initially, namely the restraint of aggregate demand, required strong enough monetary restrictions that the fiscal stimulus would not become inflationary. This led, not only to high interest rates, but (because of the reduction of inflation) to historically high real interest rates. This helped create, according to this approach, the second half of the so-called twin-deficit problem. To understand this problem, we need to recall the discussion of crowding out in chapter 3. The idea is that the pool of available savings to be utilized by private-sector businesses for investment is the very same pool from which government borrows when it runs a deficit. If the Federal Reserve refuses to create enough new money to finance the deficit, interest rates rise, potentially crowding out private-sector borrowers.

However, the simple crowding-out analysis ignores the fact that international financing became more and more available in the 1970s and 1980s, in part as a result of the massive buildup of dollar holdings by certain OPEC countries, particularly Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates. When interest rates rose dramatically in the United States and inflation began to subside, holders of dollars overseas as well as holders of foreign currencies began to see financial investment in the United States as very attractive. Interest rates were high, and with inflation reduced, the long-term prospects for the international value of the dollar were good. Remember, if you’re not an American, investing in a dollar-denominated interest-bearing asset means risking a fall in the value of the dollar vis-à-vis one’s own currency over the lifetime of the investment. The relative value of currencies can be quite volatile, as international holders of the dollar discovered in the middle and late 1970s. Thus, the decline in inflation and the seriousness with which the Federal Reserve pursued tight monetary policy reduced the risks of reigniting inflation and future falls in the value of the dollar.

So one reaction to the rise in interest rates in the United States was a big increase in the desire of foreigners to own assets denominated in dollars. This led to a rise in the international value of the dollar. Just as fears over the inability of the Federal Reserve to control inflation in the late 1970s had led to a decline in the value of the dollar, so belief that the Federal Reserve had gotten serious led in the 1980s to a rise in the value of the dollar. Note that that rise dates from the fourth quarter of 1980 and continued, with two short interruptions, till the value of the dollar against the currencies of the major industrial nations peaked in the first quarter of 1985.14 Thus, this increase predates the impact of the tax-cut-induced fiscal deficit by two years.

As mentioned before, changes in the international value of the dollar have a major impact on the competitiveness of exports from the United States and competitiveness within the United States of imports from abroad. Just as the reduced value for the dollar improved the ability of U.S. producers to export and reduced Americans’ willingness to buy foreign imports in the late 1970s, so the reverse occurred in the early and middle 1980s. A good measure of this is the merchandise trade deficit. In relation to GDP, it was less than 1 percent for 1979–82 and rose to 1.5 percent in 1983, 2.6 percent in 1984, 2.7 percent in 1985, and 3.0 percent in 1986.15

What Harm Was Done by the Twin Deficits?

The concern of mainstream economists throughout the 1980s centered on these twin deficits. The fear was that the large budget deficits would have two kinds of permanent consequences. The first was the straightforward crowding out of domestic investment. In fact, many argued that the relatively low percentages of gross domestic product devoted to investment after the boom year of 1984 can be traced to the high real interest rates engendered for most of the decade.16

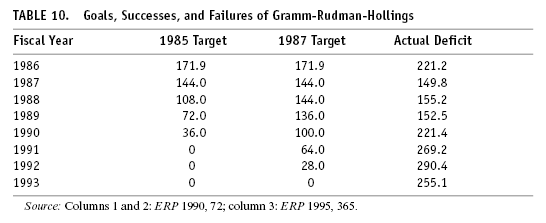

The Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act did not succeed in permanently reducing the federal deficit. Table 10 shows the deficit targets (for both versions of the act) as well as the actual deficit for those fiscal years.

For three years (fiscal 1987 to 1989) Congress and the president were able to approximate the targets of the 1987 law. In 1990 the recession destroyed all semblance of an effort to keep up with the Gramm-Rudman schedule. Just before that failure became apparent, the Council of Economic Advisers in their February 1990 report stated,

When viewed from a broad perspective, GRH has provided valuable control over Federal spending. . . . A focus simply on the difference between GRH targets and annual budget deficits ignores important progress in controlling deficits. Since the adoption of GRH, the deficit has fallen steadily as a percentage of GNP. Moreover, deficits are far below the path projected prior to the adoption of GRH. . . . Furthermore, the rate of Federal debt accumulation has stabilized.17

Economist Benjamin Friedman disagreed. He attacked the high deficits of the Reagan years in a 1988 book, Day of Reckoning. He argued that there is clear evidence of crowding out after 1984. He argued that Federal Reserve tight monetary policy initially caused the real interest rate to be quite high in 1981 and 1982.

But even after monetary policy eased, real interest rates still remained high. Most of the drop in nominal interest rates merely reflected the slowing of inflation rather than a decline in the real cost of borrowing. . . . For the previous thirty years, the real interest rate on short-term business borrowing had averaged less than 1 percent. But it was over 5 percent in 1981, over 4 percent in 1986, and nearly 4 percent in 1987. Our new fiscal policy, generating ever larger deficits even in a fully employed economy, had long since replaced tight monetary policy as the reason for high real interest rates.18

Note that his argument assumes that beginning in 1984, the economy was close enough to full employment for the deficit to begin crowding out private investors.19

The real interest rate can affect investment because it is part of the cost of productive capital investment. It is a cost in two senses. Explicitly, corporations and other businesses contemplating productive investment will usually have to resort to the capital market to borrow some if not all of the funds. The gross profit rate they receive must be sufficient to pay interest on those funds, pay taxes on the net profits, and still realize an acceptable after-tax rate of return. The tax changes introduced by the Reagan administration went a long way toward raising the after-tax profit rate, but, unfortunately, the rise in the real interest rate reduced the pretax profit rate.

The rise in the real interest rate also represents what economists call an opportunity cost. This means that even if the owners of businesses have accumulated sufficient internal funds to make investments without borrowing from the capital market, they still will take account of the rate of return their money could earn them if it were invested in interest-bearing assets. Productive investments that might be engaged in if the interest rate were 5 percent appear unattractive by comparison if the interest rate is, say, 8 percent. Even businesses with internal funds available will choose to put more of them into interest-bearing investments when rates rise.

The second cause for concern was that the increased foreign purchases of American dollars and the consequent rise in the international value of the dollar would result in a long-run decline in competitiveness. Overseas markets lost to American exporters would be hard to win back. American consumers who become used to buying imported products when they suddenly become cheaper as a result of the rise in the international value of the dollar will not automatically switch back to domestically produced products. This is true even if, as occurred after 1986, the dollar were to depreciate, removing the temporary advantages for foreign imports.20 In addition, Robert Blecker pointed out,

national firms could shift production overseas during the period of overvaluation, paying the fixed, sunk costs of relocation while they are low in terms of the home currency. Then, after the home currency depreciates, those firms can maintain foreign production as long as the operating costs abroad, converted to domestic currency, remain low enough to allow for profitable export back to the home country. In some product lines, little or no domestic production may remain after the overvaluation is reversed.21

Beginning in 1984 with the publication of the Brookings Institution’s and Economic Choices and continuing throughout the 1980s, mainstream economists and many political figures kept up a drumroll of complaint about the twin deficits.22 In the mid-1980s, the Federal Reserve, acting in concert with central bankers in Europe and Japan, forced down the value of the dollar with some expansionary monetary policy. This led to a couple of years of falling real interest rates and rapid monetary growth.23 The effect on the exchange rate was as expected. The international value of the dollar declined from its peak in the first quarter of 1985 till the end of 1987. Though it drifted downward from that point, the fall was slight.24 Meanwhile, the trade deficit peaked in 1987 and began to decline as a percentage of GDP. However, by 1992, despite the fact that the value of the dollar had basically returned to its 1980 level, the trade deficit was a higher percentage of GDP than in 1980.25

The important element of this twin-deficits criticism of the 1980s prosperity is that financing significant levels of domestic investment and government deficits by borrowing from abroad cannot go on forever. In other words, using foreign savings to fuel the engine of growth is unsustainable. If the U.S. economy could generate sufficient domestic savings to finance both investment by the private sector and the politically desired excess spending by government, there would be no problem; in fact, in such a situation, the government deficit would be an essential element of aggregate demand and necessary to keep GDP as close to its potential as possible. But borrowing from overseas involves a trade deficit (by definition, the only way to borrow dollars from overseas is to first send more dollars overseas to buy imports) that has potential long-term consequences. Such borrowing also depends on the willingness of foreign investors to continue increasing the percentage of dollar-denominated assets in their investment portfolios. That increased percentage is going to reach some limit. When that occurs, the flow of funds from overseas will be reduced.

More significantly, the critics of the twin deficits argued that such borrowing is worthwhile only if the proceeds are invested productively so that repaying the loans is made easier. Here, analogies to individual borrowing and business borrowing are useful. Virtually everyone who owns a home takes out a mortgage to finance it. That is a perfectly legitimate way of consuming the services of housing. The benefits you get from owning your own home flow to you every year you live in it.26 Thus, paying for it on time as you utilize it is totally acceptable. Obviously, if you suffer a financial reversal, say, you lose your job, you may not be able to sustain the mortgage payments and may have to sell the house and spend less on housing. But note that as long as you can afford to pay for utilizing the service of the house, that monthly mortgage payment is not cutting into your current consumption. Compare that with taking out a home equity loan and using it for a vacation. When the vacation is over, you must cut back on consumption of other items every month following the vacation for the life of that loan. And since this home equity loan was not invested in some enhancement of the home that increases the value to you of living in it, you get no benefits month after month to justify having to make those higher payments. In that situation, increasing the borrowing on your home creates a burden for yourself in the future.

Consider the same situation for a business. No one would argue that a corporation that issued twenty-year bonds to finance major construction projects to expand productive capacity was engaging in an irrational business practice. The newly constructed capacity should increase the revenue flow to the corporation over the life of the facilities, and that revenue should be more than sufficient to pay the interest on the loans. (If not, then financial officers will have made serious errors in calculation.) Now imagine, instead, that the corporation borrowed from the bond market and chose to buy a vacation retreat for top executives. Unless the increased ability of executives to “play and work together” in such a setting improves the productivity of the corporation, repaying those loans will have to come out of the revenue stream, thereby cutting into profits and dividends. Such a use of borrowed money would have negative consequences for the judgments of the corporation by both the stock and bond markets. A management team that authorized such use of borrowed money might very soon find itself the target of a takeover bid, unless, of course, it satisfied the investing community that executive vacations were a legitimate investment in the future well-being of the business.

The moral of these two examples is that borrowing for investment purposes is legitimate, but borrowing for current consumption is not. Of course, individuals do borrow for current consumption, but when that happens they must reduce consumption while they pay back the loan. Borrowing for investment, however, should produce increased flows of revenue out of which the loan and the interest can be paid back.

Returning to the problem of the twin deficits, we can note that the centerpiece of the criticism leveled by mainstream opponents of the policies of the 1980s is that such borrowing financed, not productive investment, but instead a “long consumption binge”: “Between 1980 and 1987, consumer spending has grown almost 1 percent faster per annum than total spending in our economy.”27 In fact consumption as a percentage of GDP rose throughout the 1980s, rising from 64 percent of GDP in the depths of the recession of 1982 to 66 percent of GDP at the end of the decade.28

Benjamin Friedman also raised a point later echoed by H. Ross Perot. Friedman argued that after foreigners had accumulated large amounts of dollar-denominated financial assets, some began to cash in those assets to purchase real assets: factories, real estate, farmland, and so forth.29 He warned that foreign ownership of American land and capital would be disadvantageous to the United States. Here he is in direct conflict with another member of the mainstream opposition to Reagan’s program, the secretary of labor in Clinton’s first term, Robert Reich. In his book The Work of Nations, Mr. Reich argued that the modern international enterprise has so many internationally interconnected parts that the nationality of the “ownership” of the corporation is virtually irrelevant.30

This is another very interesting issue. When politicians and aca-demics in the 1960s and earlier argued that the spread of American and other advanced countries’ businesses into the Third World was a modern version of imperialism, they were generally dismissed.31 The argument was that in underdeveloped sections of the world, foreigners who obtain control of productive resources hire local factors of production, increase the output of the domestic economy, and, in the case of production for export, increase the foreign-exchange holdings of the economy, facilitating the importation of important capital goods. Foreign owners have access to foreign sources of capital and bring into the economy advanced technology. Since their goal is long-term profitable operations, their motivations will, according to this approach, be only marginally different from those of a local owner of the same business. The only potential problem is repatriation of profit, but that is counterbalanced by the inflow of financial capital for investment purposes.

The “imperialism interpretation” sees foreign ownership of local wealth as a method of exploiting local factors of production. The most extreme example of this is in so-called enclave economies, in which the advanced sector uses foreign factors of production to exploit domestic resources and the resulting products are then exported. The income from this successful business is mostly spent on compensating foreign owners, leaving little benefit to the domestic economy. Repatriation of profit, far from being compensation for inflows of foreign capital, often exceeds the inflows because many of the foreign-owned companies raise their (financial) capital locally instead of bringing it in from abroad.

The United States is not an underdeveloped nation with an advanced enclave more tied to the international than to the domestic market. The problem, however, is a similar one.

Becoming a nation of tenants rather than owners will jar sharply against our traditional self-perceptions. America will no longer be an owner, directly influencing industrial and commercial affairs abroad. At the same time, we will have to accept the influence and control exercised here by foreign owners. The transition is certain to be demoralizing and probably worse if potentially dangerous frictions also develop as the ordinary resentments of renters against landlords and workers against owners increasingly take on nativist dimensions. . . . World power and influence have historically accrued to creditor countries.32

Friedman argues that just as Britain was able to exercise considerable influence during the nineteenth century as an international creditor, the U.S.’s

influence as a genuine world power . . . gained further momentum when this country first became a major lender to Britain and France at the time of World War I and then dramatically gained maturity during and after World War II. . . . the political, cultural and social position that traditionally accrues to the foreign banker became this country’s due. . . . Nations can lose influence as well as gain it. . . . The fiscal policy we have pursued in the 1980s has spawned just such a reversal. . . . the predictable consequences will inevitably follow, as America increasingly depends on foreign capital—a change that cannot help but alter America’s international role.33

These arguments echo the views of radicals. The influence that Friedman sees accruing to creditors is the power that radicals emphasize. The fear of loss of national sovereignty emphasized by candidate Perot and others is part of this analysis, also. Stated as precisely and carefully as possible, the complaint seems to be that when the health of one’s economy is dependent on the willingness of international bankers and foreign central banks to cooperate with your economy’s needs, the national political structure must make its policy judgments not merely on the basis of what the majority of people in the country want, but on the basis of what will be acceptable to the international bankers and foreign central banks.

Suppose the majority of the people in the United States desired a policy of very low unemployment. In order to avoid the high interest rates that would follow from an excessively expansionary fiscal policy, suppose Congress were to order the Federal Reserve System to keep interest rates constant as the unemployment rate falls. Such a policy would entail rapid expansion in the money supply to finance the budget deficit to prevent crowding out and higher interest rates. Anticipated inflation would make investments in interest-bearing assets relatively unattractive, particularly to foreigners, who would see in the expected inflation and future decline in the international value of the dollar an unacceptably low rate of return in their own currency. The result would be a serious drain of financial capital from the United States. Not only would foreigners cash in their interest-bearing assets and move their capital to some safer haven, but Americans with money to invest might choose to put it into overseas interest-bearing notes. The decline in the value of the dollar and the acceleration of inflation might create a serious crisis of confidence in the business community, and investment might decline, even with the high levels of aggregate demand.

On the other hand, consider the same policy in the context of the United States as a net international creditor. The rise in government deficit-spending to finance the low-unemployment policy would merely divert funds that were previously flowing overseas to domestic spending. The position of an international creditor would give the economy a cushion from which to engage in a fully domestically oriented program without concern about an international collapse of the value of the dollar. Thus, becoming an international debtor does remove some of a nation’s independence in setting economic policy.

The response, which comes not merely from supporters of the Reagan policy like Bartley but also from mainstream critics like Robert Reich is that whether or not one is an international creditor or debtor, the internationalization of production and capital markets has proceeded to such an extent that even a national economy as large and diversified as the United States must be concerned about international competitiveness and the judgment of international investors. In other words, it is not the debtor or creditor status that reduces national independence. National independence has already been reduced. The successful economies will attract international capital, and the unsuccessful economies will be punished by the judgment of international investors and consumers.

Despite this initial agreement, Reich and Bartley remain at opposite ends of the spectrum. Whereas Bartley sees the inflow of international capital as a judgment on the success of the Reagan policies of fostering incentives and rapid investment growth, Reich sees potential long-term erosion of America’s economic strength due to the neglect of what he considers the most important roles for government, provision of good education and maintenance and extension of physical infrastructure.

Reich titled his book The Work of Nations in an effort to hark back to Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. To Reich, the wealth of a nation depends on the kind of work done by its people. If one does highly skilled, creative work of high value to the modern business enterprise, one will be handsomely rewarded. Other work will be rewarded at the lowest common international compensation rate, no matter how efforts at protectionism might try to delay or reverse that process. The key to locating business activity depends, according to Reich’s analysis, on the availability of a pool of high-quality employees and good communications and transportation infrastructure. In addition, there must be a high quality of social infrastructure as well, so businesses can attract the high-quality employees they wish to hire to their current location. Thus, for Reich, the issue is not the inflow of foreign capital to purchase American assets that signals long-term economic difficulties. Instead it is the type of assets purchased that is crucial. If foreigners build facilities where researchers into product development, corporate leaders, inventors, and general researchers locate and produce their various “outputs” (often intangible), the nation is economically healthy over the long term. If foreigners buy up real estate or ongoing companies and reinvest the profits elsewhere, that is an indication that the infrastructure and skilled-educated labor force in the United States are not as advantageous as those available overseas. In such a situation, the alarm sounded by Friedman would be justified, but for a different reason.

To summarize the various elements of the mainstream critique, we can identify a number of points. The high budget deficits coupled with the Fed’s severe anti-inflationary policies caused a much deeper than necessary recession and a less prosperous recovery. Particularly important was the relative sluggishness of productive investment in the private sector caused by the high real interest rates (crowding out occurred) and the reduced productive investment within the public sector (particularly infrastructure and education). The method by which crowding out was partially avoided, namely the financing of much investment by relying on overseas savings, contributed to a significant increase in the international value of the dollar, with serious consequences for the long-run competitiveness of American exports, producing significant permanent penetration of the domestic market by imports. The accumulation of the ownership of American assets in the hands of foreigners translates into a long-run decline in American economic independence, as defined by Benjamin Friedman and Ross Perot.

Thus, this critique boils down to identifying serious unsustainable elements in the post-1983 recovery. The high-interest-rate, high-government-deficit policy cannot be sustained because it ultimately involves borrowing indefinitely from overseas. The rise in government deficit spending over time increases the percentage of the government budget that must be devoted to interest payments. It also crowds out some private-sector investment. Government spending on the military, as opposed to projects that could be considered investments in the society’s future, such as infrastructure and education, has long-run consequences for productivity growth. As infrastructure and education deteriorate, the desire of international businesses to locate in the United States will decline. This is not something that will be noticed overnight, but over a decade or so, the decline will have serious consequences.

Radicals Respond to Conservative Economics

Those working in the radical tradition emphasize the exercise of power and the distribution of income in assessing the success or failure of an economic policy. As mentioned in chapter 4, radicals argued that for business and political leaders in the United States, the social safety net had become too expensive. The ability of labor to resist falls in the real wage rate had been the cause of the stagflation of the 1970s. The regulation and tax policy of the government had been too solicitous of low-income people, workers on the job, and the environment. It was necessary, from the point of view of the ruling circles in the United States, to reestablish the power of capital.

According to the majority of economists working within the radical tradition, the attempt to alter the balance of power within the economy in favor of investors and businesses and away from the population in general and labor in particular was an almost complete success. In After the Wasteland, Samuel Bowles, David Gordon, and Thomas Weisskopf argued specifically that the effort to reduce the regulation of business, to ease the tax burden on investment income, to redistribute income from the majority of the population to the top 20 percent (and even further to the top 5 percent), and to shift the priority of federal spending toward defense all succeeded.34

Just as the very nature of the success in the early postwar period created the seeds of future difficulty in the 1970s, so the methods used to bring success to the Volcker-Reagan program insured that these would not produce the expected results. The ultimate goal of the reassertion of power by business interests was to raise profitability sufficiently to stimulate productive capital investment, which would then feed on itself to produce further increases in profitability in a “virtuous circle” of profits, productivity growth, economic growth, more profits, and so on. Along the way, benefits of higher incomes and better jobs would trickle down to the rest of society.

It didn’t happen. First of all, the benefits never trickled down. Inequality grew dramatically, as did poverty. Unemployment re-mained high for virtually the entire decade. Note that unlike the mainstream critique, which sees these results as failures of the Volcker-Reagan program, the radicals see the growing inequality and high unemployment rates as keys to the success of the program. Inequality and high unemployment constituted the stick that forced wages down as a way of fighting inflation while attempting to enforce increased productivity in the workplace, mostly through increasing the effort expended by workers. In analyzing this shift in the balance of power, Samuel Bowles and Juliet Schor have devised a measure known as the cost of job loss. When one loses a job, the best way to avoid a permanent reduction in income is to immediately get another job that is just as good. Obviously, the higher the rate of unemployment, the less likely finding that job is. So one aspect of the cost of job loss depends on the rate of unemployment. However, another important aspect of the cost of job loss is how much of the fall in income is cushioned by the social safety net—particularly unemployment compensation payments. Bowles, Gordon, and Weisskopf track this cost of job loss and argue that after declining significantly between 1966 and 1973, it rose only 1 percent on average between 1973 and 1979 and then only two more points between 1979 and 1989.35

This, and the shifting tax burden and shifting spending priorities, did increase the share of profits in the national income. From a class perspective, the rise in the share of income going to the “investing class” should raise investment. Here Bowles, Gordon, and Weisskopf identify important contradictions in the policy of business ascendancy. The very methods by which the share of profits rose tended to discourage, rather than encourage, investment. For example, they agree with Benjamin Friedman and other critics of the twin-deficits problem in identifying high real interest rates as one of the culprits.

But there is another, even more significant by-product of the increased power of the business owners. The higher-than-average unemployment rate for the recovery was coupled with a lower-than-average capacity utilization rate. With a low capacity utilization rate, despite the rise in the share of profits, the expected rate of profit will not be sufficiently high to justify expansion of capacity. The reason should be obvious. What rationale is there for a business to expand capacity if present capacity is not being fully utilized? Making a productive investment does not depend solely on having the current profits to finance it; it depends crucially on the projection of rising demand for output that current capacity cannot meet. Until capacity utilization gets high enough to force businesses to increase that capacity in fear of losing customers to their competitors because of their future inability to expand output, expected rates of profit from such investment will not be high. Thus, the important tool of business success—the high unemployment and low capacity utilization—became the reason for the sluggish investment. Note that this analysis adds an important element to the mainstream critique, which was based, as we have seen, almost exclusively on the high real interest rate.

Another argument from the radical perspective is that reduced opportunities for productive investment, in part caused by high real interest rates, but also caused by the inherent stagnation tendencies in our economy, has resulted in a explosion in purely financial investments. With productive investment highly risky due to the overhang in excess capacity, purely financial investments in mergers, interest-bearing notes, real estate, and so forth permit high rates of return with much less risk.

Economist Robert Pollin has connected the long-run tendency toward stagnation to growing debt-dependency in the entire nonfinancial sector, not merely the government sector, as emphasized by Friedman.

This can be seen when . . . we divide twentieth-century US financial activity into [long] cycles. . . . between 1897 and 1949, the net borrowing to GNP was remarkably stable at around 9 per cent for each long cycle. This relationship also held between 1950 and 1966. However,. . . between 1967 and 1986, this figure rose to 14.6 per cent, a 60 per cent increase over the historical average.36

Pollin believes that one of the results of the stagnant growth in incomes and profits has been the increased reliance of private households and businesses on credit. First this happens “to sustain expenditure growth in the face of declining revenues.”37 In addition, within the business sector, borrowing for speculative (purely financial) investments takes place for reasons mentioned above. The increased private-sector borrowing found investors not merely in the United States but abroad. “The US trade deficit . . . [was] instrumental in supplying foreigners with dollars which were then available to be recycled into the US financial market.”38 Note that this is not merely the result of high real interest rates but of a structural change in the borrowing habits of the entire nonfinancial sector, not only the government.

The combined impact of these structural changes that resulted from the long-run stagnation tendencies has been to weaken the ability of large budget deficits to stimulate the economy, as was possible in the past. The potential for crowding in as argued by Keynesians such as Robert Eisner depends on the expectations business leaders will have of profitability should they decide to create new assets. To the extent that stagnation tendencies have dampened profit expectations, the positive impact of budget deficits is reduced.

In addition, the entire period since World War II has seen the important role of budget deficits in countering downturns in the business cycle. This meant that unlike the period before World War II, business cycle downturns did not include any actual price deflation, and defaults were limited.39 This might appear to be a positive trend, but not so. Michael Perelman points out in The Pathology of the American Economy that “market economies require strong competition and strong competition breeds depressions and recessions.”40 The ability of government deficits to prevent major recessions for much of the period after World War II has, in Perelman’s view, changed our economy from “a strapling [sic], accustomed to the dangers and the rigors of a competitive jungle” to “a tragic bubble-boy who weakens daily in an atmosphere of loving care.”41 This weakness is what economist Hyman Minsky identified as financial fragility. In brief, this concept relates to the rising ratio of debt to assets in the private sector. Prior to World War II, recessions would enforce default on those firms that had borrowed too much. This periodic removal of the weakest businesses contributed to the strengthening of the financial structure of the entire economy. But as Pollin notes, “In the absence of debt deflations no automatic mechanism exists for discouraging the sustained growth in private debt financing.”42 This means that a higher and higher percentage of businesses increase their vulnerability to reductions in income. It stands to reason that a firm with a strong balance sheet can weather even a couple of years of low or negative rates of return by taking on more debt. On the other hand, a firm already deeply in debt will be stuck with a larger payment responsibility vis-à-vis income and be unable to tap the credit markets for new loans. Thus the argument from the mainstream that the growth in the period after 1983 was based on unsustainable forces is supplemented by the radical economists who emphasize that stagnant real growth leads to an explosion in purely financial investments that increases the financial fragility of the economy. That, too, is unsustainable, as the entire country discovered when the savings and loan crisis broke in 1988.

The International Aspects of the Radical Critique

In the international sphere, radicals identify another contradiction by which the very elements of success create the subsequent difficulties. One of the causes of the squeeze on profitability in the 1970s was the rise in the relative price of imports, particularly—but not exclusively—petroleum. The period of declining value for the dollar may have made exports competitive, but they also increased the cost of imports. With the rise in the value of the dollar in the first five years of the 1980s, the relative costs of imported products declined accordingly. However, the method of solving the problem of high prices for imports involved the same rise in the real interest rate that kept unemployment high and capacity utilization low. Another result of the appreciating dollar was the rise in the trade deficit. The trade deficit is another element of sluggish aggregate demand that keeps capacity utilization low and therefore interacts with the high real interest rate to dampen investment.

In addition, the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy is constrained, not merely by the need to combat domestic inflation, leading to higher unemployment rates and lower capacity utilization rates, but because domestic credit markets have to attract foreign savings. The trade deficit makes dollars available to overseas lenders that could be sent back to the United States to purchase interest-bearing assets. However, that does not guarantee the willingness of foreign wealth-holders to purchase such assets. For that, they need expectations of high real rates of return denominated in their own currency. Thus, not only do they need a high enough interest rate to compensate for expected inflation in the United States, they need some assurance of the (relative) stability of the exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and their currency. This means that the Federal Reserve has to be extremely careful not to recreate the negative expectations many foreign wealth-holders formed during the period of “malign neglect.”43 This is the very same problem identified by Benjamin Friedman when he complained about the disadvantages of being a net international debtor.44

Thus, in a number of respects, those who believe that the basic problem confronting the United States economy in the past twenty-five years has been the emergence of a general tendency toward stagnation are relying on the same evidence Friedman used to argue that the irresponsible budget deficits of the Reagan era had harmed the economy. The difference is that Friedman blames the financial problems on the Reagan budget deficits, while radicals believe the budget deficits were a result of the tendency toward stagnation—a response to that tendency that did not fix the problem but merely increased financial activity and financial fragility.

Changing the Balance of Power in the Economy

Bowles, Gordon, and Weisskopf argue that the response to the difficulties experienced by the economy in the late 1970s led to a concerted attempt to increase the power of business. They argue that that effort was only an apparent success. The increased power was bought with self-destructive increases in the unemployment rate and the real interest rate. Unless more basic structural changes in the behaviors of workers and managers were to occur, profitability and productivity growth would become unacceptably low when the unemployment rate and real interest rate fell.45 They conclude that there were no such basic changes despite the many successes of the Reagan Revolution.

Among the elements of the structure that Bowles, Gordon, and Weisskopf investigate is the intensity with which workers do their job. Recall that in chapter 2 we identified two different ways output per unit of labor can be increased. The first way enhances the ability of workers using the same effort to produce, the second involves increasing intensity.

If one can imagine conflicting desires on the part of workers and their supervisors as to how much intensity workers expend during the hours they are working, then the power of capitalists to push the level of intensity closer to its physical and mental maximum depends on their ability to cajole or bribe workers into willingly raising their levels of intensity or to threaten or punish workers if they refuse to raise their levels of intensity. Bowles, Gordon, and Weisskopf attempted to measure the elements that might cause workers to voluntarily raise their efforts with numbers like the index of worker satisfaction,46 real spendable hourly earnings,47 and the inverse of the industrial accident rate.48

They also attempted to measure the “stick” with which workers could be threatened for not working diligently enough. These numbers involved the cost of job loss, the amount of inequality among workers, and the percentage of supervisors involved in the production process. These require some analysis. The cost of job loss has already been developed. Suffice it to say that the higher the burden placed on a worker who loses a job, the more likely that worker will be anxious to work hard enough to please a supervisor. With a relatively modest social safety net and the prospect of a significant time spent unemployed, such a worker will be most anxious not to get fired. The attitude expressed in the 1970s by the country music song “Take this Job and Shove It” can quickly disappear when this job is the only one around and scores of unemployed people are dying to take it.

A higher percentage of supervisory personnel indicates that workers have a greater chance of being “caught” not working hard enough. Thus, for any given cost of job loss the probability of being forced to endure that cost increases if there are more supervisors. Most of the people who said, “Take this job and shove it” said it out of earshot of a supervisor. The more supervisors, the less likely they’ll be out of earshot.

Finally, inequality is measured in order to capture the extent to which workers can band together to make it difficult for the owners and supervisors to enforce the speed and intensity they hoped for. There is tremendous evidence, going back to the early struggles over Taylorism,49 that organized workers can thwart the efforts of owners to force them to work faster. One of the most dramatic episodes was the struggle in Lordstown in 1972.50

From this perspective, inequality among wage earners goes hand in hand with declining union membership.51 Both play a role in eroding the ability of workers to resist increased intensity on the job. Thus, inequality should show up in increased productivity statistics. Arrayed against this is that fact that the median income of male year-round full-time workers actually declined over the decade from 1979 to 1989. The “cost of job loss” in that sense actually declined.52 However, since the availability of unemployment compensation had been reduced and the average length of time one spent unemployed had increased, the decline in the cost of job loss due to declining wages was more than offset, but just barely.

This discussion of the intensity with which people work is just one element in Bowles, Gordon, and Weisskopf’s attempt to see if long-term structural changes had come to the economy as a result of the Reagan Revolution. They conclude that they had not. The lower level of capacity utilization and the higher level of unemployment merely contributed to a rise in the “apparent power” of capital. If Bowles, Gordon, and Weisskopf are right, then the only way to preserve the profitability that did exist in the 1980s would be to permanently keep unemployment high and capacity utilization low. If they are right, recoveries must be stopped well short of any meaningful measure of “full employment.”

In summary, radicals argue that since the Reagan-Volcker program did not solve any of the structural problems in the American economy, it is not surprising that it produced such disappointing results. The key point is that the apparent success was bought with such reductions in living standards, capacity utilization, and aggregate demand that profitability for productive investments was not restored sufficiently. The flight into purely financial investment was thus a symptom of the lack of attractiveness for the investment that would really have a positive impact on people’s lives and long-run growth prospects in the economy.

How Do We Play Referee?

In the three strands of arguments on which we have focused in this chapter, certain issues keep rising to the forefront. All agree that inflation was reduced and contained, though some believe the cost of that victory was too high. A very interesting result of the reduction of, and containment of, inflation has been the historical destruction of the alleged link between budget deficits financed by money creation and the rate of inflation. As mentioned in chapter 3, when government budgets are financed by borrowing from the Central Bank rather than from the public, and when the Central Bank permits the money supply to rise sufficiently to cover that deficit, there is no crowding out of private-sector activity. Those who believe the words of Milton Friedman, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,”53 conclude that the result of financing deficits with money creation will ultimately involve an increase in inflation. Yet even the most casual glance at the relationship between the government deficits of the 1980s, the rate of growth of money, and the rate of inflation should indicate how strongly the facts of 1983–90 contradict this proposition.54 Perhaps because the pre-1980 budget deficits were relatively small as a percentage of GDP, the assertion that money-financed deficits were inflationary could be made on the basis of monetarist research alone. However, the experience of the large postrecession deficits that were paralleled by rapid expansion of the money supply in 1985 and 1986 but accompanied by declining rates of inflation should lay to rest the simplistic connection between deficits and inflation.

When it comes to identifying the impacts of the Volcker-Reagan program other than on the rate of inflation, there is tremendous disagreement. Was investment high and rising or low and stagnant? Did productivity growth rebound dramatically, or was it disappointing? What about employment? The unemployment rate? Once more we are faced with the question with which we began this investigation. What is the basis on which we can judge something a success or a failure? The next chapter attempts to use the historical experience to create a basis for judgment about whether the results of the Reagan-Volcker program can be considered a success or a failure.