Notes

Chapter 1

1. The first shutdown lasted from November 14 to November 19, 1995 (New York Times, November 20, 1995, 1). The second began on December 16 (New York Times, December 17, 1995, 1; for details on what was shut and what wasn’t, see p. 40). See also Congressional Budget Office, The Economic and Budget Outlook: Fiscal Years 1997–2006 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1996), 9.

2. An article in the Wall Street Journal pointed out how much President Clinton had moved since the previous year. Whereas the previous year’s (February 1995) budget proposal had projected deficits of $200 billion per year for the foreseeable future and contained five years of spending cuts totally $81 billion, the 1996 proposal had increased the projected cuts to $234 billion, permitting a deficit of zero by 2002 providing the economy remained at a steady rate of growth. With this reversal, President Clinton had surrendered to the Republicans. See Jackie Calmes, “Clinton’s Fiscal ’97 Budget Reflects Major Shift toward Ending Deficits and ‘Big Government,’” Wall Street Journal, February 6, 1996, A16.

3. For details of that bill, see U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means, 1996 Green Book: Background Material and Data on Programs within the Jurisdiction of the Committee on Ways and Means (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1996), 1325–1418.

4. The most significant cuts in the 1995 budget that Congress had passed and that the president had vetoed were in the Medicare and Medicaid programs. To measure such cuts, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) starts with a “baseline budget.” This budget indicates how much it would cost to maintain current services over the period of time being considered, based on the CBO’s estimates of costs and revenues, if no changes were enacted. Then the changes passed by Congress are measured against this baseline. This procedure is the source of the argument as to whether these are cuts or merely slowing the growth of spending. In fact, slowing the growth of spending makes it impossible to provide services at the current level to the growing population eligible for those services (the retired, the poor, the disabled in the case of Medicare and Medicaid) with the increased cost of providing those services over time. In December 1995, compared to the CBO baseline, recalculated according to the most recent predictions about the economy’s next six years, the budget passed by Congress would have reduced federal spending by approximately $401 billion, of which approximately $359 billion would have been in Medicare and Medicaid. It also would have cut taxes approximately $229 billion (Jim Horney, “Memorandum: Updated Estimates of the Balanced Budget Act of 1995,” Congressional Budget Office, December 13, 1995). The 1997 law, by contrast, cut approximately $127 billion in toto while providing a modest $90 billion in tax reductions (and an additional $11 billion in refundable tax credits) through 2002 (see “Budgetary Implications of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997” and “Budgetary Implications of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997” in letter, June E. O’Neill, director, Congressional Budget Office, to Franklin D. Raines, director, Office of Management and Budget, August 12, 1997.)

5. For an analysis of Clinton’s goals and methods on the road to this compromise see Martin Walker, “He Stoops to Conquer: Clinton’s Budget Pact Shows His Messy Means to a Grand End,” Washington Post, May 11, 1997, C1, C5. For initial coverage of the agreement, see the New York Times, July 30, 1997, A16, A17.

6. The Employment Act of 1946 states that

it is the continuing policy and responsibility of the Federal Government to use all practicable means, consistent with its needs and obligations and other essential considerations of national policy with the assistance and cooperation of industry, agriculture, labor, and State and local government, to coordinate and utilize all its plans, functions, and resources for the purpose of creating and maintaining, in a manner calculated to foster and promote free competitive enterprise and the general welfare, conditions under which there will be afforded useful employment, for those able, willing, and seeking to work, and to promote maximum employment, production, and purchasing power. (Quoted in Stephen Kemp Bailey, Congress Makes a Law [New York: Columbia University Press, 1950], 228.)

The responsibility to “promote maximum employment” has been interpreted as requiring efforts to respond to the increase in unemployment that accompanies recessions. In 1978, this law was amended by the Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act to include a specific target of 4 percent unemployment.

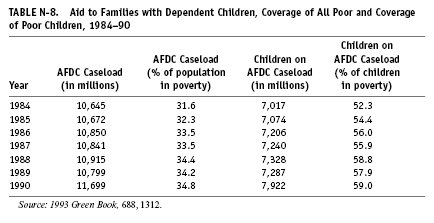

7. There is a significant strand in economic analysis that suggests that paying the unemployed compensation may actually delay workers’ finding new jobs because the benefit subsidizes the time without a job and reduces the urgency with which they look. See Martin Feldstein, “The Economics of the New Unemployment,” Public Interest 33 (1973): 3–42. Similarly, there is a strongly held view, exemplified by the work of Charles Murray in Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950–1980 (New York: Basic Books, 1984), that providing cash assistance to the poor as welfare actually causes poverty rather than reducing it. This point of view became the intellectual justification for the Republican proposals that led ultimately to the abolition of Aid to Families with Dependent Children, the program that provided a federally guaranteed cash grant to children in poor, single-parent families.

8. To give one example, total federal spending as a percentage of total economic activity (gross domestic product) stayed around 10 percent for the entire decade of the 1930s, rose to around 15 percent after World War II, hovered around 19 percent from the end of the Korean War till the late 1960s, and climbed to near 21 percent by 1979 (Economic Report of the President 1996 [Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1996], 368; henceforth these annual reports are abbreviated ERP, with the year indicated). Considering total government expenditures (including state and local outlays for things like police, fire, education, and public assistance), we see an upward trend from 25 percent of total activity to 30 percent between 1960 and 1979.

9. The United States Central Bank consists of a system of twelve regional federal reserve banks whose actions are controlled by a seven-member Board of Governors in Washington appointed by the president (and subject to confirmation by the Senate) for fourteen-year terms. However, for the most important policy decisions, the controlling unit is the larger Federal Open Market Committee, which consists of the seven governors and the presidents of five of the regional banks (with the president of the New York Federal Reserve Bank always among the five). The actions of the Federal Reserve System are completely independent of the three branches of government, except that Congress may change the rules by legislation at any time. The president and secretary of the Treasury have no direct influence on Federal Reserve policy. All they can do is make speeches and attempt persuasion. A president wanting to force a change in policy would have to propose legislation to Congress. For a massive study of both the history and recent experience of the Federal Reserve System, see William Greider, The Secrets of the Temple: How the Federal Reserve Runs the Country (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1987).

10. A more detailed table, which goes back only to 1968, is provided in the 1996 Green Book, 1321. Programs redistributing income on the basis of need for medical, food, and cash assistance went from 4.9 percent of the federal budget (in 1968) to 8.5 percent of the budget in 1978. Note that these are fiscal years, not calendar years. The fiscal year went from June of the previous year to the end of May of the numbered year until 1976; and from 1977 on, from October 1 of the previous year to the end of September of the numbered year. Thus, “fiscal 1968” was from June 1, 1967 to May 31, 1968. “Fiscal 1978” was from October 1, 1977 to September 30, 1978.

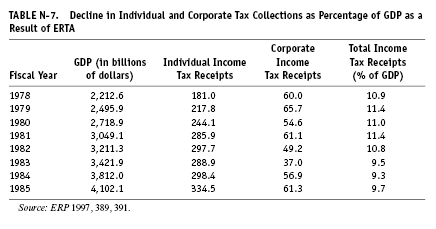

11. ERP 1997, 391.

12. The Congressional Budget Office analysis of the 1997 law shows a cut in Medicare spending of $115 billion in the years 1998 to 2002 over the predicted path of spending if no changes were to occur. See letter, June E. O’Neill, director, Congressional Budget Office, to Senator Pete V. Domenici, chairman, Committee of the Budget, United States Senate, July 30, 1997, table 4.

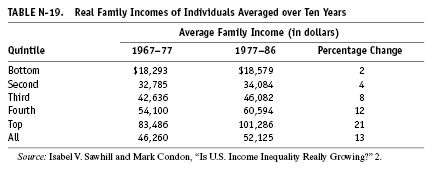

13. Daniel P. McMurrer and Isabel V. Sawhill, “Economic Mobility in the United States,” Urban Institute no. 6722 (1996).

14. After the Republican success in the 1994 congressional elections, the Contract with America was published in book form, edited by Ed Gillespie and Bob Schellhas (New York: Times Books, 1994).

15. Representative Meek had asserted that

in 1980 a group of Republican candidates came to the Capitol steps and pledged that, if elected they would enact a supply-side miracle that would raise defense spending, cut taxes across the board, and still eliminate the deficit in 4 years. . . . They rammed their supply-side quick-fix through the Congress, and claimed it would solve all of our problems. . . . Their latest contract calls for: Another round of defense spending increases and a longer list of pie in the sky tax cuts.

What they do not tell us is that their contract will do two other things: First blow a $1 trillion hole into their balanced budget promise; and second, produce another tax windfall for the wealthy while leaving the middle class and the poor behind. (Congressional Record [September 29, 1994], 10254)

16. For example, see the following remarks by Speaker-designate Newt Gingrich on November 11, 1994: “It is impossible to take the Great Society structure of bureaucracy, the redistributionist model of how wealth is acquired, . . . and have any hope of fixing them. They are a disaster. They . . . have to be replaced thoroughly from the ground up” (Contract with America, 189).

17. It should be noted that some scholars and not a few citizens believe that this theoretical analysis is just a veneer behind which the true purpose of economic policy is to redistribute income and opportunity to those already in power, who have always been able to manipulate the political system to their ends. Thus, the role of government has always been rather extensive, and the cry for less government involvement always ignores the things government does to subsidize investments and profits of already large and successful enterprises. (On this point, note the increase in government activity and spending related to law enforcement, the punishment of criminals, and the defense establishment promised by the Republicans in the Contract with America, 37–64, 91–113.) This book will allude to this alternative point of view at times, but for the most part, we will conduct our discussion based on the mainstream analysis. The reason is that even if this alternative explanation of economic policymaking were true (and there is plenty in the historical record consistent with it), the changes in policy during the 1980–97 period are significant and worth exploring on their own terms. Second, the debates in the mainstream do not credit this alternative approach, and in the interest of dialogue with that mainstream, it is essential to accept some of the most basic premises, at least for the sake of the current discussion.

18. The federal budget deficit fell from $255 billion in fiscal 1993 to $22 billion in fiscal 1997. See Robert Pear, “Budget Heroes Include Bush and Gorbachev,” New York Times, January 19, 1998, A12. See also ERP 1998, 372. Federal spending fell from 21.7 percent of total income to 21.1 percent between fiscal 1992 and 1996 (ERP 1997, 300, 391).

19. The economic proposals are contained in the following promised laws: “The Fiscal Responsibility Act . . . The Personal Responsibility Act . . . The American Dream Restoration Act . . . The Senor Citizens Fairness Act . . . The Job Creation and Wage Enhancement Act” (Contract with America, 9–10; see also 17–18). The specific proposals in these laws were a balanced-budget amendment to the Constitution, a denial of welfare to minor mothers, a rigid two-years-and-out limit on welfare eligibility and a cut in the dollars available for welfare, a five-hundred-dollar-per-child tax credit for all taxpayers making up to two hundred thousand dollars a year, an increase in the amount of money Social Security recipients can earn while collecting their pensions, a repeal in the 1993 tax increases on some Social Security income, a cut in taxes on business income including capital gains, and a reduction in government regulation of business and federal regulation of the states.

20. For the agreement, see Jerry Gray, “Congress and White House Finally Agree on Budget 7 Months into Fiscal Year,” New York Times, April 25, 1996, A1, B13.

21. The marginal tax rate is the percentage of the next dollar you stand to earn by, say, accepting a higher-paying job that you would have to pay in taxes. With a tax system that starts with some income free of taxation and then has a series of rising rates (such as our federal income tax system), the average tax rate is just the total level of taxes divided by total income. The marginal rate will always be higher than the average rate so long as some income is tax free (and therefore subject to a zero rate). It is the contention of some economists, including Lindsey, that high marginal tax rates discourage productive economic activity. See Lawrence B. Lindsey, “Simulating the Response of Taxpayers to Changes in Tax Rates,” Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1985. For a concise, less technical discussion, see Lawrence B. Lindsey, The Growth Experiment: How the New Tax Policy Is Transforming the U.S. Economy (New York: Basic Books, 1990), 53–80.

22. This is the conclusion ultimately reached by Samuel Bowles, David M. Gordon, and Thomas Weisskopf in After the Wasteland: A Democratic Economics for the Year 2000 (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1990). See especially pp. 121–69. For a short summary of the regressive tax changes, see Lawrence Mishel and Jared Bernstein, The State of Working America, 1994–1995 (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1994), 93–108.

23. A supporter of Reagan-style tax cuts even before Reagan was elected president, Jude Wanniski wrote a book (How the World Works [New York: Touchstone/Simon and Schuster, 1978]) arguing that the ups and downs in all of world history can be traced to regimes of low versus high taxation.

24. See for example, Spencer Abraham, “The Real 1980s,” The World and I, April 1996, 94–100. For counterarguments see Gary Burtless, “Tax-Cut Potions and Voodoo Fantasies,” The World and I, April 1996, 100–102; and Michael Meeropol, “A Smoke Screen for Brutal Interest Rates,” The World and I, April 1996, 102–3. See also Alan Reynolds, “Clintonomics Doesn’t Measure Up,” Wall Street Journal, June 12, 1996, A16.

25. Still others deny that the distribution of income has become more unequal.

Chapter 2

1. “Oeconomicus,” Xenophon in Seven Volumes, trans. E. C. Marchant (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968), vol. 4. The original conception of the ancient Greeks and Romans was very practically related to personal management of one’s property (vii).

2. However, as noted in the previous chapter, income distribution is very important as a political issue. There is also an argument from the radical tradition in economics that the distribution of income and wealth has an important impact on economic growth. See pp. 59–63.

3. Of course this is in societies like the United States. In most traditional societies (and human beings lived in such traditional societies for hundreds of thousands of years before settled agriculture and civilization developed more complex organizations for producing food, clothing and shelter) cooperation occurs without modern-style leadership. True, there was a designated leader, but tasks were carried out based on tradition, not direct orders. Even in the United States and other modern economies, the leadership of certain organizations, such as cooperatives and partnerships, is not so hierarchical. Here voluntary cooperation is much more explicit, and, in fact, in many cooperatives extensive rules govern that cooperation.

4. Harry Braverman, Labor and Monopoly Capital (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1974), 54–69 and 85–151.

5. In fact, even in the classic management literature, both the necessity of imposing order and maintaining control (the Marxist emphasis) and the fostering of a cooperative spirit coexist. For example, Henri Fayol, who published Administration industrielle et generale in 1916 (General and Industrial Management, trans. Constance Storrs [London: Isaac Pitman and Sons, 1949]), listed fourteen universal principles of management. Though most of the principles emphasize centralizing control over the work process (and therefore over the workers) in the hands of management (19–40), there is an intriguing fourteenth point, “Esprit de corps . . . Harmony, union among the personnel of a concern, is great strength in that concern” (40). In the late 1920s, the famous Hawthorne studies discovered (quite inadvertently) that varying physical surroundings of workers had much less important an effect on how well and hard they worked than did the attitudes of the workers themselves. Elton Mayo quoted from a private internal report on these studies as follows,

The changed working conditions have resulted in creating an eagerness on the part of operators to come to work in the morning . . .

The operators have no clear idea as to why they are able to produce more in the test room; but . . . there is the feeling that better output is in some way related to the distinctly pleasanter, freer, and happier working conditions . . .

. . . much can be gained industrially by carrying greater personal consideration to the lowest levels of employment. (The Human Problems of an Industrial Civilization [New York: Viking, 1960], 65–67)

The inescapable conclusion of the Hawthorne Studies was that emotional factors related to morale were more important in determining the productivity of workers than physical factors.

Mary Parker Follet, lecturing in 1933, felt that she had discerned among the most forward-looking businesses the practice of developing collective responsibility, not only between different branches of the administration of a business, but down to the workers on the shop floor,

wherever men or groups think of themselves not only as responsible for their own work, but as sharing in a responsibility for the whole enterprise, there is much greater chance of success for that enterprise . . . when you can develop a sense of collective responsibility then you find that the workman is more careful of material, that he saves time in lost motions, in talking over his grievances, that he helps the new hand by explaining things to him and so on. (Freedom and Co-Ordination, Lectures in Business Organization [New York: Garland, 1987], 73)

I am indebted to my colleagues Julie Siciliano and Peter Hess of the Department of Management at Western New England College for calling my attention to these sources.

6. In the context of environmental degradation and fears of world overpopulation, to state that growth appears to be have become permanent since the Industrial Revolution might be considered the height of hubris. I do not want to underestimate the dangers posed by environmental deterioration. However, it is a fact that the increased knowledge that has created the technology that is endangering our planet has also given us the potential information necessary to harness the technology and, in the words of the ecologist Barry Commoner “make our peace” with the planet (Making Peace with the Planet [New York: Pantheon, 1990]).

7. The importance of government in stimulating private investment with subsidies and other incentives should not be underestimated. For example, at the height of the laissez-faire approach to free enterprise during the nineteenth century, the U.S. government provided a tremendous subsidy to the railroads. First the government used the armed forces to defeat the Plains Indians and remove them from their land. Second, the government granted thousands of acres of land to the railroads along their right of way, land that the railroads were able to sell quite profitably. Virtually every major surge in investment in the United States can be traced to indirect or direct subsidies as a result of government activity, whether making war, building roads, or the like. Nevertheless, it is true that the actual spending of the investment funds is done by a private entity.

8. Contract with America, 23.

9. H. Ross Perot in United We Stand emphasized the interest burden on the federal taxpayer of the four-trillion-dollar national debt. He asserted,

By 2000 we could well have an $8-trillion debt. Today all the income taxes collected from the states west of the Mississippi go to pay the interest on that debt. By 2000 we will have to add to that all the income tax revenues from Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, New York and six other states just to pay the interest on that $8 trillion.

Central to the criticism leveled by Perot at the political leaders is a linkage between the unacceptable behavior of the economy in the 1990s and the ballooning national debt. In his very first chapter, he begins by mentioning some large layoffs. He then mentions the national debt and its growth every day as a result of the government deficit and concludes, “Does anyone think the present recession just fell out of the sky?” (United We Stand: How We Can Take Back Our Country [New York: Hyperion, 1992], 5)]. The reader is left with the inescapable conclusion that Perot wants us to believe the large debt caused the recession. We will explore these and other arguments about the alleged burdens of deficits and debt below. See pp. 43–44, 162–63, 170–74.

10. In Restoring the Dream, ed. Stephen Moore (New York: Times Books, 1995), 65–81, the House Republicans continue their arguments and promises made in the Contract with America. Their laments about the damage being done by budget deficits adds virtually nothing to what was said in the first volume. There is a reference to the absorption of national savings, the problem just referred to of “crowding out” private investment. The only other specific problems involve the increased percentage of federal spending devoted to interest payments on the debt and a reference to the fact that a rising percentage of the debt is held by foreigners. Both of these “problems” are not as serious as they make them out to be and are discussed on p. 170 and tables N-13 and N-14. Everything else in these pages is just rhetoric. Readers skeptical of the assertions made here may want to consult any textbook on the principles of economics. There is usually a chapter on deficits and government debt. A more sophisticated but highly accessible analysis can be found in Robert Eisner’s The Misunderstood Economy: What Counts and How to Count It (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1994), 89–119. See also James K. Galbraith and William Darity Jr., “A Guide to the Deficit,” Challenge, July–August 1995, 5–12. For a recently published work that examines the intellectual history of American concern with budget deficits in great detail and argues for other damage that could potentially be done by some forms of deficit spending, see Daniel Shaviro, Do Deficits Matter? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), esp. 28–150.

11. There is a school of economics known as the “public choice” school whose most prominent member, James Buchanan, received the Nobel Prize in economics in 1989. This school contends that there is an inexorable political pressure for government to expand its involvement in the economy based on the self-interest of government officials, elected and appointed, as well as the intensity of desire on the part of beneficiaries of government largesse. According to Buchanan, the future generations who must pay interest on the debt contracted before they were born have no political say in the decisions made by their grandparents, and thus the deck is politically stacked against them. In Democracy in Deficit: The Political Legacy of Lord Keynes (New York: Academic Press, 1977), Buchanan together with Richard Wagner blamed deficit spending for the ability of government to increase its spending in the economy. “Elected politicians enjoy spending public monies on projects that yield some demonstrable benefits to their constituents. They do not enjoy imposing taxes on these same constituents. The pre-Keynesian norm of budget balance served to constrain spending proclivities. . . . The Keynesian destruction of this norm . . . effectively removed the constraint” (93–94). Later on, they assert that the “bias toward deficits produces . . . a bias toward growth in the provision of services and transfers through government” (103). For a detailed examination of the “public choice” school, see Shaviro, Do Deficits Matter? 87–103.

12. This was baldly admitted by Murray Weidenbaum, the first chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Reagan. At a discussion at the American Enterprise Institute, he candidly explained that concern over the deficit was necessary to counter pressure for increased government spending.

- dr. weidenbaum: I’d like to offer, hopefully, some insight into the continuing concern . . . about deficits. I think the underlying concern is . . . to control the growth of government.

- And we measure that most conveniently by outlays. Surely the pressure for government spending growth is omnipresent. What is the counter pressure? In the legislative process . . . we’re led back to the concern over deficits. . . .

- Dr. Stein [Herbert Stein, former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, then resident scholar at the AEI]: But aren’t you worried that the whole trend of this discussion is reducing the inhibitions about running deficits, and therefore, weakening this restraining force against government spending.

- Dr. Weidenbaum: Maybe that’s why I made my comment.

- Dr. Stein: Well, that’s a good reason to make the comment but something more needs to be said then. That is, you need to reestablish some defensible reason for not having deficits. If you’ve now told us that they don’t cause inflation, they don’t crowd out. You see, it is not sufficient, as we know, for a group of economists to sit around and say, “Well, a deficit of a hundred billion dollars doesn’t have these adverse effects,” because you’re dealing with a bunch of Congressmen out there, and if we say 100 billion is OK, they will ask why not 200 or why not 300.

- They have a certain feeling about zero [that is, a balanced budget]. Zero is an intuitively appealing number. But we haven’t found any other intuitively appealing rule, and that’s what we’ve been missing. (American Enterprise Institute, “Public Policy Week,” mimeo transcript, December 8, 1981, qtd. in Robert Bartley, The Seven Fat Years [New York: Free Press, 1992], 191–92)

13. See Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962) and his collaborative work with Rose Friedman, Free to Choose: A Personal Statement (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovitch, 1980).

14. Qtd. in Conald Bedwell and Gary Tapp, “Supply-Side Economics Conference in Atlanta,” Economic Review of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta 57 (1982): 26.

15. See the quotations from Buchanan in note 11.

16. In fact there is another way a government can finance deficit spending, called “running the printing presses.” It involves printing money and using it to pay for what the government needs. Such behavior had its origins in the days when governments collected precious metals and turned them into coins at the mint. In order to get more coins out of the precious metal, the mint was ordered to mix in some cheap metal with the gold or silver. This process was known as “debasing the currency,” and the result was that the regime’s coinage came into ill repute and individuals did not want to accept it at face value. Recent history has shown that wholesale resort to printing money to finance government expenditures leads to very rapid inflation—such as in Germany in 1922, when millions of marks were needed for a loaf of bread. This result has led many to argue that it is irresponsible to meet government spending needs by printing money over and above tax revenue. Printing bonds and selling them on the open market is considered more responsible because the rising national debt supposedly acts as a check on too much money creation. However, judicious printing of new money to finance some small percentage of the government budget might very well not lead to hyperinflation. This process, technically known as monetizing the debt, is frowned upon mainly because when the government borrows by issuing bonds, bankers make profits by placing them and investors have a secure place to invest funds. If the government just printed money at a slow enough pace not to accelerate inflation, the bankers would be out their cut.

17. The last time the federal government ran a surplus was in fiscal 1969 (ERP 1994, 359).

18. Contract with America, 23.

19. Eisner, The Misunderstood Economy, 51.

20. This is probably a good place to mention that much of the argument against government spending in general is in reality aimed at government activity that redistributes income. As mentioned in chap. 1, the Contract with America, 91–113, called for increased government spending on national defense. The Republican majority in Congress has since 1994 attempted to reverse the decline in defense spending projected by both the Bush and Clinton administrations, while proposing dramatic cuts in Medicaid, Medicare, and transfer payments to the poor. Even those who rail against spending in general usually treat the defense budget as sacrosanct. Many have argued that this is because the defense budget is an indirect subsidy to large businesses, benefiting the kind of people who make large contributions to members of Congress and whose investment activity is the key to economic prosperity. See chap. 9, n. 18.

21. The National Bureau of Economic Research identifies recessions as periods during which the real GDP (that is, GDP corrected for inflation) falls for two consecutive quarters. Table N-1 combines the NBER’s dating of post–World War II business cycles beginning with the 1948 recession. Each peak marks the end of a period of prosperity and the beginning of a recession. Each trough marks the point where a recession bottoms out and a recovery begins. Table N-1 shows the quarter before and after each peak and trough to give an idea of the way unemployment and capacity utilization rates behave around the peaks and troughs of business cycles. Later we will examine these and many other facts of recent economic history quarter by quarter in the years since 1960.

22. Thus, even though the recovery from the 1990 recession began in the first quarter of 1991, there was not one quarter during the rest of 1991 in which real GDP grew as fast as 2 percent (ERP 1997, 307). Thus, it is not surprising that the unemployment rate actually rose from 6.5 percent in the quarter the recovery began to 7.5 percent in the third quarter of 1992 before it began to decline. Similarly, the capacity utilization rate did not reach 80 percent until the fourth quarter of 1992. This made the 1991 recovery the most sluggish in the postwar period.

23. Note that this is a creation of something physical. Common usage often describes investment as any spending of money to acquire an income-generating asset. By that definition, investment includes buying stocks and bonds as well as physical assets like machines and buildings. For the purposes of describing the impact on aggregate demand, however, we restrict the meaning of investment to physical assets. Purely financial investments actually involve the transfer of ownership rights of already created physical assets and thus are not counted as part of the GDP. This is not to suggest that such financial investments are unimportant; far from it. See pp. 128, 156–57 for some discussion of the impacts of purely financial investments.

24. The public-choice field of economics analyzes that government decision making may not respond to an generalized “public interest” but to the narrow interests of particular constituencies. See James Buchanan, The Demand and Supply of Public Goods (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1968).

25. ERP 1997, 37, 38.

26. ERP 1996, 282.

27. ERP 1997, 389. These are fiscal years.

28. Real investment as a percentage of real GDP fell from 16 percent to 14 percent between 1984 and 1989 (ERP 1996, 282), the federal deficit fell from 5 percent of GDP in fiscal 1983 to 4 percent of GDP in fiscal 1986, and the national debt fell from 57.6 percent of GDP to 39.5 percent of GDP between 1960 and 1969. As a percentage of GDP, this debt is much lower than was the much smaller absolute debt of $271 billion in 1946 (ERP 1997, 389). The ratio of debt to GDP was over 100 percent in 1945 and 1946; that is GDP was actually lower than the national debt in those years.

Chapter 3

1. The rate of growth averaged 4.07 percent between 1960 and 1969 and 2.85 percent between 1970 and 1979.

2. For the periods 1960–69 and 1970–79, productivity growth averaged 2.41 and 1.33 percent, respectively; unemployment averaged 5.58 and 6.21 percent, respectively; and capacity utilization averaged 84.86 and 82.58 percent, respectively.

3. Dean Baker, “Trends in Corporate Profitability: Getting More for Less?” Technical Paper, Economic Policy Institute, February 1996, table 1. A full business cycle begins with a peak and continues through the next trough to the next peak. Alternatively, it can begin with a trough and continue through the next peak to the next trough (see chap. 2, n. 21 and table N-1). The calculation of profit rates is made for the year before each cyclical peak, since the rate of profit usually turns down before the whole economy does. Thus, for example, using the profit rate of 1969 in the 1959–68 business cycle would have actually introduced profit data more appropriate for the next business cycle.

4. I use 1978 as the end point because in 1979 the Census Bureau changed data collections, and a spurt of unanticipated inflation caused median earnings of year-round, full-time workers to fall for that year. I did not want that one year’s experience to skew the data. As it is, the change from the 1960s to the 1970s remains quite striking.

5. A variety of inflation rates are constructed and published by the various branches of the federal government. For the purposes of identifying the misery index, I have chosen the most widely publicized inflation rate, the consumer price index. Not all of the components of the consumer price index apply to all people; for example, a homeowning family with a fixed-rate mortgage is not affected by rising housing costs so long as the family stays put. As many economists will emphasize, however, the knowledge of general inflation has a discomforting impact on people even apart from those higher prices they actually pay.

6. Let’s consider two numerical examples from the period of history covered in this book. Consider a mortgage loan entered into in 1965 with a ten-year maturity. The nominal interest rate in 1965 averaged 5.81 (ERP 1994, 352); the inflation rate (measured by the consumer price index) was 1.6 percent (ERP 1997, 370). If we assume that inflation rate was accurately anticipated by both lenders and borrowers, then the real interest rate these mortgage lenders were expecting was 4.21 percent. Within three years, when the rate of inflation had accelerated to 4.2 percent, the actual real rate of interest received by mortgage lenders was 1.61 percent. In 1969 it was 0.31 percent; in 1970 it was even lower (0.21 percent) because inflation was 5.7 percent. Beginning in 1973 and running through 1975, the rate of inflation was higher than the mortgage rate of interest contracted in 1965. This translated into a negative real interest rate. The borrowers found the reduction in the real burden of their repayment of principal greater than the nominal interest rate they had to pay. The lenders lost real income on those loans.

Now let us consider a mortgage loan contracted in 1981. The nominal rate of interest for a ten-year mortgage averaged 14.7 percent and the rate of inflation in the consumer price index was 10.3 percent. This represented a real interest rate of 4.4 percent, assuming correct anticipation by lenders and borrowers. The rate of inflation deceleration after 1981 was so dramatic that the real burden of the mortgage interest rate rose in 1982 to 8.5 percent and only once fell below 10 percent for the rest of the time till maturity. In other words, borrowers were faced with a real interest burden more than twice as great as they anticipated when they contracted the loan.

7. Some businesses can set their prices and stick to them because they have few competitors, who will most likely match their price rather than provoke a price war. In the most general sense, the distinction needs to be made between businesses that are “price takers” and those that are “price makers.” The earliest empirical work on the significant ability of certain firms to control prices was by Gardner C. Means. He identified industries that responded to the falloff in demand during the Great Depression by keeping prices relatively stable and reducing output. These industries he characterized as those with administered prices (that is, they were price makers) as opposed to those industries (such as agriculture) in which prices fell dramatically but output did not (in other words, price takers) (Industrial Prices and Their Relative Inflexibility, Senate Document No. 13, 74th Congress [Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935]). This analysis was in opposition to traditional economic theory, which was built on the idea that most businesses (and sellers of factors of production) are price takers because they are subject to competition with a large number of competitors that sell roughly identical products (in the textbooks, the definition of this type of competition is even more restricted: they are all selling indistinguishable standardized products, like Class A corn, for example, or shares in AT&T). Beginning in the early twentieth century, economists began to recognize the significance of imperfectly competitive markets. Most textbooks now acknowledge the existence of competition among such a small number of firms that they are able to set prices. The technical term for this market structure is oligopoly. John Kenneth Galbraith referred to this sector of the economy as the “planning system” to identify the ability of these firms to plan output and control prices (John K. Galbraith, The New Industrial State [Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1967], and Economics and the Public Purpose [Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1973]). In one strand of the radical tradition, what Galbraith calls the planning system is called the “monopoly sector” of the economy, and the entire economy is identified as monopoly capitalism (see, for example, Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy, Monopoly Capital [New York: Monthly Review Press, 1966]; and John B. Foster, The Theory of Monopoly Capital [New York: Monthly Review Press, 1989]).

8. This would amount to a tax rate on my real income of 72 percent.

9. In actual experience, inflation induces most taxpayers to avoid taxable interest income. Instead, potentially taxable interest-bearing securities are bought by pension funds and other tax-exempt organizations and insurance companies and banks with very low effective tax rates. Individuals who wish the security of interest income buy tax-exempt bonds issues by states and municipalities. See C. Eugene Steuerle, Taxes, Loans, and Inflation: How the Nation’s Wealth Becomes Misallocated (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1985), 9–18, 57–80.

10. Paying interest of $10,000 a year on a $100,000 loan with 5 percent inflation means the real burden of repayment is only $5,000 per year.

11. This would represent fully 72 percent of the real cost of my interest payments. Tax expert C. Eugene Steuerle argues that the interaction of inflation and the ability to deduct the full nominal interest paid induces unproductive investment activity, for example, excess construction of residences, office buildings, and shopping malls, just for the purposes of reaping the tax advantages. See Taxes, Loans, and Inflation, 57–114.

12. Let us assume a 36 percent tax rate. With no inflation, the tax of $36,000 is 36 percent of that real gain. Now let us assume inflation over five years causes an average increase in prices of 25 percent. The $100,000 gain is only $75,000 in increased purchasing power because $25,000 merely makes up for the inflation. But the tax burden is still $36,000, only it now represents 48 percent of the ($75,000) real gain.

13. To return to our specific numerical example, with a 50 percent exclusion and a 25 percent cumulative inflation over the five years, the real gain is $75,000, and the tax rate of 36 percent is applied to only $50,000. Thus, the tax is $18,000, which is only 24 percent of $75,000. If the real gain were only $50,000, applying the tax rate of 36 percent to half the dollar gain ($100,000) produces $18,000 in taxes, which is 36 percent of the real gain.

14. See chap. 1, n. 6, which quotes the Employment Act of 1946.

15. Fiscal policy is defined as all governmental decisions involving taxation and spending. Monetary policy consists of actions of the Federal Reserve System (often merely referred to as “the Fed”) to change the rate of growth of money and/or to change interest rates. As mentioned above (chap. 1, n. 9), the United States has an independent Central Bank. The seven governors of the Federal Reserve Board are appointed by the president for fourteen-year terms to protect their independence. An expansionary fiscal policy would involve increased spending or decreased taxation or some combination of both. A restrictive fiscal policy would involve decreased spending or increased taxation or some combination of both. (For a variety of reasons, most economists believe that balanced increases of spending and taxation are expansionary and balanced decreases are restrictive, but that is quite controversial; see pp. 47–48 and chap. 3, n. 43.) An expansionary monetary policy increases the rate of growth of the money supply, aiming for a reduction in interest rates. A restrictive monetary policy decreases the rate of growth of the money supply, perhaps even contracting it, aiming for an increase in interest rates. How the alteration in money growth affects interest rates and the economy at large is the subject of a great deal of controversy. For an accessible and accurate summary of what he calls the monetary hydraulics, see Greider, Secrets of the Temple, 31–33. For a reasonable introduction to the controversy over how monetary policy works or does not work, see Richard Gill, Great Debates in Economics (Pacific Palisades, CA: Goodyear, 1976), 353–62.

16. Jude Wanniski’s book (How the World Works) was published in 1978. The introduction of “supply-side” economics to the public at large occurred even earlier in his article “The Mundell-Laffer Hypothesis,” Public Interest 39 (spring 1975): 31–57. In addition to the proposed cuts in the individual income tax, there were major proposals for liberalizing depreciation deductions for businesses. For details of some proposals, see ERP 1981, 76.

17. See, for example, John N. Smithin, Macroeconomics after Thatcher and Reagan: The Conservative Policy Revolution in Retrospect (Aldershot, UK: Edward Elgar, 1990), 1–4, 8–24.

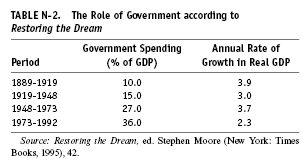

18. On this issue, see Contract with America, 125–41; Restoring the Dream, 37–52. On p. 41, the latter book has a diagram headlined “As Washington Grows, the Economy Slows.” In the diagram the percentage of the economy covered by government spending is set against the rate of growth of real gross domestic product. Table N-2 reproduces the numbers in table form. Despite the rise in the rate of growth of GDP in the third period even as government spending rose, the long-run trend is obviously an inverse one.

19. Murray Weidenbaum, “America’s New Beginning: A Program for Economic Recovery,” in Two Revolutions in Economic Policy, ed. James Tobin and Murray Weidenbaum (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1988), 294. Note that the focus is on “excessive government spending,” yet nowhere in this discussion are deficits blamed for the economy’s problems. Instead there is a prediction that deficits will decline to zero and a passing reference to the “alarming trends” of rising deficits and rising spending over the decade of the 1970s (p. 302).

20. ERP 1981; ERP 1984.

21. See Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom, as well as ERP 1982, 27–33. For a more extreme superlibertarian view, see Murray Rothbard, Power and Market, Government and the Economy (Kansas City, MO: Sheed Andrews and McMeel, 1977).

22. In 1993, economic historian Douglass C. North won the Nobel Prize in economic science for his work on how institutions interact with economic actors to make it easier or harder for economic growth to occur. One can see the proposals in the Contract with America relating to increased spending on police and prisons, increased sentences for violent criminals, and legal reform to reduce the costs to business and individuals from “frivolous” lawsuits as an effort to re-create what Republicans see is an appropriate framework within which such a market economy can function (Contract with America, 37–64, 143–55).

23. William Baumol, J. C. Panzar, and R. D. Willig, Contestable Markets and the Theory of Industry Structure (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982).

24. The Contract with America devotes an entire chapter to the proposition that the Clinton administration budget cuts have weakened the defense establishment to the point where the so-called hollow military of the late 1970s is in danger of being re-created (Contract with America, 91–113). The sequel volume, Restoring the Dream, 115–18, has proposed significant privatization of federally run activities such as the Naval Petroleum Reserve, the Air Traffic Control System, and certain Amtrak routes.

25. In the 1990s, there is an effort to take this principle even further. Areas of activity previously the sole responsibility of government, such as the running of prisons, have been proposed for privatization. Private companies contract with a state government to house a certain number of prisoners, getting paid a fixed fee and making their profit by delivering the “service” to the taxpayers at a lower cost than if the state paid the costs directly. With prison building on a dramatic upsurge in the past decade and prison populations rising dramatically, this is a great new frontier for profitable activity on the part of the private sector.

26. ERP 1982, 30–31.

27. Given the incomes of all consumers, given the tastes and preference of these consumers, and given the capital and land and skills of the labor force available to be used by businesses as well as the state of technology, the satisfaction achieved by each and every consumer that is greater than or equal to the price they actually pay for what they buy exactly equals the sacrifice society has had to endure to produce the last unit of the product sold. If this occurs in every market, then this maximizes satisfaction for society as a whole. The problem of externalities is that the price paid by people does not equal the true cost to society; the satisfaction experienced by an individual does not equal the true benefit to all of society.

28. Economists would make the comparison by summing the present value of all expected net earnings of the farmer for the rest of his or her productive life. This would create what is called the capitalized value of the farmer’s income stream. In reality, such a calculation would be very uncertain, because it actually depends on how one thousand dollars, say, five years from now is discounted to create its present value. In addition, farmers may place some kind of premium on maintaining their way of life, even if the dollar value of a lifetime in farming is lower than what could be obtained by selling out to a developer. Finally, the farmer’s time horizon may include the projected incomes of his or her children and grandchildren.

29. Murray Weidenbaum, The Future of Government Regulation (New York: Anacom, 1979), 23. It should be noted that the Weidenbaum approach is not without its critics. Some have argued that his cost estimates are too high. See, for example, John E. Schwarz, America’s Hidden Success: A Reassessment of Public Policy from Kennedy to Reagan (New York: Norton, 1988), 91–98. Others have attempted to measure benefits to show that the benefits do justify the costs. See, for example, Mark Green and Norman Waitzman, Business War on the Law: An Analysis of the Benefits of Federal Health and Safety Enforcement, preface by Ralph Nader, 2d ed. (Washington, DC: Corporate Accountability Research Group, 1981). However, it is not our intention to argue these points. It is important to develop the full conservative diagnosis of what ailed the economy because the solutions proposed and attempted by both the Reagan administration and the Republican majority in Congress since 1994 aims to change public policy to meet these alleged problems.

30. Monetarists believe that the rate of growth in the money supply is the crucial determinant of the rate of growth of nominal GDP, that is, GDP uncorrected for inflation. They argue that deviations of the rate of growth of money from the current trend have a direct impact on GDP, but only after a lag of uncertain length. (They also believe that the actual division of the impact between price increases and output increases is unpredictable in the short run.) Therefore, the monetarists have argued against using discretionary changes in monetary policy to combat too much unemployment or inflation. To do so would just as likely be destabilizing as not. For a detailed monetarist historical overview, see Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1963). See also Milton Friedman, “The Role of Monetary Policy,” American Economic Review 58 (March 1968): 1–17.

31. For the original multiplier concept, see R. F. Kahn, “The Relation of Home Investment to Unemployment,” Economic Journal 41 (1931): 173–93. The marginal propensity to consume and resulting multiplier are developed in all textbooks on the principles of economics. See, for example, N. Gregory Mankiw, Principles of Economics (New York: Dryden Press, 1998), 717–18; and Joseph E. Stiglitz, Economics, 2d ed. (New York: Norton, 1997), 674–77.

32. See Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom, chap. 5, esp. p. 81.

33. Ibid., chap. 5.

34. For some examples of some of the nonsense and their common-sense refutations, see Eisner, The Misunderstood Economy, 99–103. This is not to say that there are not some potentially negative consequences should deficits and debt rise as a percentage of GDP. When that happens, the increased percentage of government revenues devoted to paying interest would reduce the ability of government to spend on other needed activities. However, most of the claims about the evils of deficit spending and the national debt focus on the “necessity” of reducing deficits to zero and “paying off” the debt. See, for example, virtually any speech by any member of Congress beginning in March 1995.

35. See A. W. Phillips, “The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861–1957,” Economica 25 (1958): 283–99.

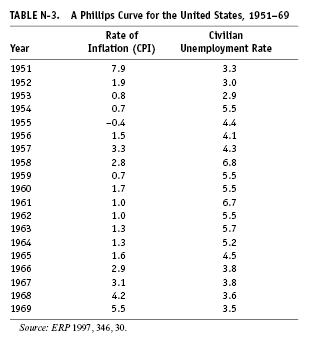

36. Table N-3 presents the unemployment rate and inflation rate between 1951 and 1969.

37. ERP 1982, 51. Table N-4 brings the Phillips Curve data from note 36 from 1970 through 1979.

38. ERP 1982, 50.

39. Within the economics profession, this view became the basis of a whole new school. Known under the general rubric of “new classical” economics, it also goes by the name of the “rational expectations” school. Very briefly, this group of economists believes that the general economy tends to an equilibrium solution and that government efforts to alter, say, the rate of growth of the economy or the level of unemployment can only have short-run impacts because in the long run, other actors in the economy will take corrective action in response to government initiatives and the economy will end up back at the same equilibrium. Thus, they strongly support the view that there is an equilibrium (“natural”) rate of unemployment toward which the economy is always tending. For a fascinating and readable analysis of this school, see Arjo Klamer, Conversations with Economists (Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Allanheld, 1984), 1–94. For criticism, see pp. 98–169. For one series of the NAIRU see Congressional Budget Office, The Economic and Budget Outlook: Fiscal Years 1998–2007 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1997), 105.

40. This may seem contradictory, but it is not. One’s marginal rate of taxation can rise even if the total percentage of one’s income paid in taxes stays the same. Consider someone with an income of $50,000 paying one rate of 10 percent in income tax. That person’s total tax is $5,000 and the marginal rate of taxation is 10 percent. Now, let us change the tax system into a two-bracket system with rates of zero percent on the first $25,000 of income and 20 percent on the second $25,000. Total taxes will still be 10 percent of income (20 percent times $25,000 = $5,000), but the marginal tax rate will have doubled. Beginning in 1964, there were a number of tax cuts that by raising personal exemptions and cutting tax rates other than the top marginal rate ended up keeping the average tax bite from rising while the marginal rate did rise.

41. It is important to understand that the tax rates shown in table 4 do not apply to the entire income of the taxpayer. Thus, someone making $25,000 in taxable income in 1980 would not owe $8,000 (32 percent of $25,000) on April 15, 1981. Instead, this person’s income tax would be the sum of the tax owed on each level of income. The first $3,400 would be tax free. The next $2,100 would be taxed at 14 percent ($294). The next $2,100 would be taxed at 16 percent ($336). Subjecting the next $17,400 to tax rates of 18, 21, 24, 28, and finally 32 percent leads to a total tax bill of $4,633. The important incentive effect of the marginal tax rate is that the extra income an individual receives as a result of making an extra effort (to take a second job, to take a higher-paying job, to make a new investment) is equal to the increase in income less the marginal tax rate. If our imaginary taxpayer with an income of $25,000 got a pay raise of $4,000, he or she would get to keep only $2,720, paying $1,280 (32 percent of $4,000) more in income tax.

42. ERP 1982, table 5-4, p. 120.

43. Assume the government raises taxes and spending by $100 billion. All of the government’s spending goes to buying military equipment, building roads, paying government employees, doing basic scientific research, thereby raising GDP. Meanwhile, some high percentage of the money paid to the government in taxes (say, $95 billion) represents a reduction in consumption expenditures, thereby lowering the GDP. But the other $5 billion in taxes paid is money that would not have been spent anyway. Thus, there is a net increase in spending of $5 billion, and that increase then is subject to the multiplier process as it ripples through the economy.

44. ERP 1982, 34–35.

45. ERP 1982, 35.

46. See, for example, Warren Shore, Social Security, the Fraud in Your Future (New York: Macmillan, 1975).

47. In 1979, 58.9 percent of the elderly would have been in poverty had they not received Social Security, unemployment compensation, and other cash payments also available universally. The other 41.1 percent with private-sector incomes above the poverty level also received Social Security. See Sheldon Danziger and Daniel Weinberg, “The Historical Record: Trends in Family Income, Inequality, and Poverty,” in Confronting Poverty: Prescriptions for Change, ed. Sheldon Danziger, Gary Sandefur, and Daniel Weinberg (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994), 46.

48. Though in the case of a millionaire, the unemployment compensation and Social Security check would (today) be subject to income taxation.

49. Leonard H. Thompson, “The Social Security Reform Debate,” Journal of Economic Literature 21 (1983): 1425–67.

Chapter 4

1. This is not true about monetarism. There was a long and lively debate in 1965 around the publication of Milton Friedman and David Meiselman’s study that sought to demonstrate the superiority of “monetarist macroeconomics” as an explanation for changes in the economy to the Keynesian multiplier. See Friedman and Meiselman, “The Relative Stability of Monetary Velocity and the Investment Multiplier in the United States, 1897–1958,” in Stabilization Policies, ed. E. C. Brown (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Commission on Money and Credit, 1963): 165–268. Friedman and Meiselman were challenged by many economists. See, for example, Albert Ando and Franco Modigliani, “The Relative Stability of Monetary Velocity and the Investment Multiplier,” American Economic Review 55 (September 1965): 693–728; and Michael DePrano and Thomas Mayer, “Tests of the Relative Importance of Autonomous Expenditures and Money,” American Economic Review 55 (September 1965): 729–51. The debate continued. See Friedman and Meiselman, “Reply to Ando and Modigliani and to DePrano and Mayer,” American Economic Review 55 (September 1965): 753–85; Ando and Modigliani “Rejoinder,” American Economic Review 55 (September 1965): 786–90; and DePrano and Mayer, “Rejoinder,” American Economic Review 55 (September 1965): 791–92.

2. For a detailed analysis that goes beyond a discussion of supply shocks to explain accelerating inflation, see Alan Blinder, Economic Policy and the Great Stagflation (New York: Academic Press, 1979). See also ERP 1978, 141.

3. Barry Bosworth, “Economic Policy,” in Setting National Priorities: Agenda for the 1980s, ed. Joseph Pechman (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1980), 43. Bosworth goes on to argue, “The experience of recent recessions . . . suggests that at best an increase of 1 percent in the unemployment rate—about 1 million persons—if maintained over a two-year period would reduce inflation by only about 1 percentage point.”

4. See Blinder, Economic Policy and the Great Stagflation, 146–52. For President Ford’s two diametrically opposed requests see New York Times, October 9, 1974, 1, 24; January 14, 1975, 1, 20.

5. The government deficit as a percentage of GDP rose from less than 0.5 percent in 1974 to 3.4 percent in 1975 and 4.3 percent in 1976 (ERP 1997, 389).

6. The key barometer of Federal Reserve policy is the short-term interest rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans, the Federal Funds rate. In 1974, that rate had risen to 10.50. In 1975, the Central Bank pursued a vigorous policy to cut that rate down to 5.82, and the rate continued to fall till the first quarter of 1977 (ERP 1997, 382–83). See table W-1 on this book’s web page, <mars.wnec.edu/~econ/surrender>.

7. The GDP deflator inflation rate was 5.6 percent in 1976 and rose to 9.2 percent in 1980 (ERP 1997, 306). The consumer price index rose at a rate of 5.8 percent in 1976 to 13.5 percent in 1980 (ERP 1997, 369). See also the inflation rates in table N-4.

8. ERP 1981, 8.

9. For the budget deficit percentages, see ERP 1997, 389 (these are fiscal years). For the recession, see chap. 2, n. 21.

10. See ERP 1981, 156–58, for an explanation of the direction of fiscal policy during 1980. It is well known that Richard Nixon always believed that the Eisenhower administration’s budget surplus in 1960 and subsequent recession was the chief cause of his narrow defeat by John F. Kennedy. Too late for Nixon, the Eisenhower administration permitted the budget to move into deficit in fiscal 1961 (0.6 percent of GDP), and the Kennedy administration raised that deficit in fiscal 1962 (1.3 percent of GDP) with the enactment of the investment tax credit combined with a five-billion-dollar increase in defense purchases. We already have seen how the Ford administration dealt with the recession of 1975. In 1970 and 1971 the Nixon administration took a number of small steps to raise the amount of fiscal stimulus. (Federal deficits rose to 2.1 percent of GDP in fiscal 1971 and stayed at 2.0 percent of GDP in 1972 [ERP 1997, 389].)

11. ERP 1997, 346. See also table N-4.

12. Between 1976 and 1979, the economy created over 10 million new jobs (ERP 1997, 340).

13. This point of view is summarized by President Carter himself in his report (ERP 1981, 3–5).

14. In 1981, the Brookings Institution’s academic journal put out a special issue on the productivity slowdown. In the editors’ summary, William Brainard and George Perry noted that the causes of this phenomenon “have remained largely a mystery. In the most comprehensive study to date, Edward Denison examined seventeen alternative hypotheses and concluded that alone or in combination they could explain no more than a fraction of the slowdown” (Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1 [1981]: vii). See also Edward Denison, Accounting for Slower Growth (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institute, 1979). Interestingly, with much more hindsight, a team of economists under the direction of William Baumol of Princeton University discovered that the slowdown in productivity of the 1970s and 1980s was actually a return to the century-long trend that had been disturbed first by a tremendous decline in growth due to the depression of the 1930s and then a tremendous increase in growth in the period between 1945 and 1972. See Jeffrey G. Williamson, “Productivity and American Leadership: A Review Article,” Journal of Economic Literature 29 (March 1991): 51–68.

15. Blinder, Hard Heads, Soft Hearts: Tough-Minded Economics for a Just Society (New York: Addison-Wesley, 1987), 24.

16. In the case of automobiles, the massive government subsidies to highway construction made automobile transportation of goods and people relatively attractive compared to rail travel and transport. There was also tremendous subsidy to housing dispersal into the suburbs with low-interest loans and tax deductions associated with home ownership. The aerospace and telecommunications industries’ dependence on government seed money and extensive research and development funds is almost self-evident. Large government purchases often become the basis of concerted business efforts to cut the cost of new technological advances. One particularly significant example is noted by the Economist.

In 1961 . . . Fairchild and Texas Instruments found themselves sitting on a clever new invention, called the integrated circuit, which nobody could afford to buy. Then, the chips cost around $120 each. By 1971, the average price was less than $42. Why the change? Mainly because President Kennedy decided to send an American to the moon—a feat which led the federal government to buy more than a million integrated circuits and taught the semiconductor industry to build them at a fraction of the initial cost. (“Will Star Wars Reward or Retard Science?” Economist, September 7, 1985, 96.)

The Internet is only the latest governm5t66666ent-created product that is now available virtually free of charge for use by the private sector.

17. The stagnation school is associated with the work of Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy in Monopoly Capital. The basic conclusion of this school is that capitalism in the twentieth century is subject to a permanent tendency for aggregate demand to fall short of potential GDP. The result is that more and more government intervention is necessary to stave off economic depressions, and even with such intervention, a tendency toward secular stagnation sets in.

This school explains the post–World War II sustained growth by stating that the massive expansion of the military during World War II had ended the depression. Then there was a short postwar consumer boom as people made up for hard times since the early 1930s. The years 1950–53 saw the Korean War, and even with the end of the war demand hardly slackened because the economy was into the suburbanization-automobilization that by the midsixties had put almost two cars in every garage and built thousands of miles of interstate highways. By the end of the 1960s, another shooting war was going on, and the economy actually pushed unemployment below the 4 percent level. With the slowdown in military spending associated with the reduction in U.S. activities in Indochina came the sluggishness of the 1970s. This was counteracted with other kinds of government spending and the creation of mountains of consumer and corporate debt, but it was not enough. The economy slipped into stagnation, and the efforts to fight it only created inflation to go along with the basic problem. For this school, the economy is successful only so long as special events, usually military spending or wars, are counteracting the basic tendency of the economy to settle into stagnation.

18. The various writers in this tradition have presented different version of this post–World War II structure (see, for example, Bowles, Gordon, and Weisskopf, After the Wasteland, 48). The text presentation is my own version based on a reading from a variety of sources as well as discussions within the Center for Popular Economics on the postwar period. The main difference between this group and the Baran-Sweezy stagnation school is that the latter sees the economy as always in danger of falling into a stagnant or worse situation absent extraordinary surges in aggregate demand. The long-swing group suggests that when a coherent structure, a social structure of accumulation, is in place, the economy generates a fairly long period of decent growth with short, mild interruptions.

19. ERP 1994, 320, 323.

20. In 1953, an American CIA operative led a joint British-American effort to overthrow the elected Iranian government, which had moved to nationalize international oil companies. That government was replaced by a monarchy headed by the shah. In 1954, the elected government of Guatemala had attempted to nationalize some of the land owned by the United Fruit Company. Under cover of protecting the hemisphere from Communist influence (the Guatemalans had bought some military equipment from Czechoslovakia), the United States again organized a coup (Bowles, Gordon, and Weisskopf, After the Wasteland, 50–51). See also Kermit Roosevelt, Countercoup: The Struggle for the Control of Iran (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979); and Steven Schlesinger and Steven Kinzer, Bitter Fruit (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1982).

21. The stagnation school, by contrast, believes that the economy had just run out of causes for surges in aggregate demand, and so the natural tendency to stagnation reasserted itself.

22. Arthur Okun, Prices and Quantities: A Macroeconomic Analysis (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1981), 83–126. On pp. 127–30 he analyzes the inflationary bias that collective bargaining may add to the process.

23. Gary Byner, president, Local 1112, United Auto Workers, qtd. in Studs Terkel Working (New York: Pantheon Books, 1974), 192–93.

Chapter 5

1. The rate of increase in the GDP deflator had averaged 6.3 percent in 1977 and 7.7 percent in 1978. In 1979, the first three quarters saw the annual rate of inflation rise to 8.6 percent and stay at 8.7 percent for the next two (ERP 1997, 306). Quarterly rates from Bureau of Economic Analysis, Department of Commerce.

2. ERP 1997, 422.

3. The best measure of the international value of the dollar compared to our major trading partners actually rose slightly between 1973 and 1976 before beginning to plummet (ERP 1997, 422).

4. The price of gold is per troy ounce. The monthly series for the price of gold is published by Metals Week and available from the Branch of Metals, U.S. Bureau of Mines.

5. The printout of monthly gold prices from the U.S. Bureau of Mines has the highest, lowest, and average price of a troy ounce of gold per month beginning in 1968 and continuing up to the present. Robert Bartley, quoting Roy W. Jastram, noted that “when one nation shows economic and political turbulence, its currency will decline as holders seek safe havens in other currencies. ‘But what happens when danger is sensed in every direction? There is one “currency” with no indigenous difficulties—gold. The cautionary demand for it is really a short position against all national currencies’” (Bartley, The Seven Fat Years and How to Do It Again [New York: Free Press, 1992], 109). Meanwhile, the Monthly Review, operating in the radical tradition, published an editorial identifying the spike in the price of gold as “Capitalism’s Fever Chart” (“Gold Mania: Capitalism’s Fever Chart,” Monthly Review, January 1980, 1–8).

6. ERP 1996, 280.

7. Greider, Secrets of the Temple, 109–16.

8. Greider, Secrets of the Temple, 109–23. Interestingly, in other analyses of the Fed’s policy reversal, much emphasis is placed on Volcker’s trip to an international bankers’ conference in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, which occurred after the decision of the Board of Governors but before the ratification of that decision by the Federal Open Market Committee. This has led some commentators to suggest that Volcker was responding to pressure from foreign central bankers, which of course was not true, since the decision had already been made. See, for example, Bartley, The Seven Fat Years, 85–86 and Blinder, Economic Policy and the Great Stagflation, 77.

9. “Statement by Paul A. Volcker, Chairman, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, before the Joint Economic Committee of the U.S. Congress, October 17, 1979,” Federal Reserve Bulletin 65 (November 1979): 889.

10. Both nominal and real Federal Funds rates 1970–91 are collected in table W-1 at the book’s web site, <www.mars.wnec.edu/~econ/surrender>.

11. Actually, these yearly figures mask some significant variations during the year. In 1980, in particular, the rate of growth of money started out at 6.7 percent (last quarter of 1979 to first quarter of 1980) but then turned negative as the economy experienced a sharp but very short (one-quarter) recession (the rate was –3.4 percent). The shrinkage of the money supply was not, of course, what the Federal Reserve had promised when it adopted monetarism. In response, the Fed shifted to an expansionary monetary policy. The rate of growth of money shot up to 15 percent in the third quarter before subsiding to 10.9 percent in the fourth. By the first quarter of 1981, the rate of growth had fallen further to 4.6 percent. Data of the Federal Funds rate and the money supply (M1) available directly from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

12. “Monetary Report to Congress,” Federal Reserve Bulletin 66 (March 1980): 177.

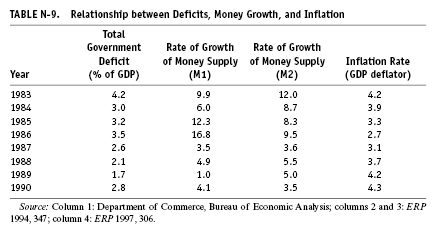

13. ERP 1994, 347. This is evidence for the charge by Greider and others that the so-called monetarist experiment was merely a political cover for interest rates high enough to wring inflation out of the economy no matter how much unemployment would be necessary. Interest rates rose high enough to get the job done, and it didn’t matter whether the growth rate of M2 or M3 slowed.

14. Beginning at 13.82 percent in January 1980, it rose to 17.61 percent in April, then fell to 9.03 percent in July (the second quarter was the time when there was a short but sharp recession), before rising to a peak of 19.08 percent in January 1981. Over the next two months it fell to 14.70 percent before rising to 19.1 percent in June. Monthly averages for the Federal Funds rate are available from the Federal Reserve Board, table J1–1. For a quarterly time series of the Federal Funds rate, see table W-1 at the web site.

15. Federal Reserve Board, table J1–1.

16. ERP 1997, 377.

17. Using annual data, both the consumer price index and the GDP implicit price deflator had the highest rate of increase in 1980 (ERP 1997, 306, 369). Using quarterly data, the first quarter of 1981 experienced the highest rate of increase in the implicit price deflator (Survey of Current Business, September 1993, 54), while for the consumer price index (urban consumers) the first quarter of 1980 experienced the highest rate of increase (Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index All Urban Consumers, U.S. city average 1982–84 = 100).

18. ERP 1984, 299. The prime rate is the interest rate banks charge their best business customers. The mortgage rate listed here is for a conventional mortgage with a ten-year repayment period.

19. The “true” real interest rate must somehow create a measure of the expected rate of inflation that the “average” borrower and lender have agreed upon when making the “average” loan agreement. There are a number of conventions that have been established to measure the expected rate of inflation. One of the simplest is to take the average of the preceding three years and assume that that is what borrowers and lenders expect inflation to be in the coming year(s). I have created such a table using the average inflation rate in the preceding twelve quarters for the “expected” rate of inflation in each quarter. In effect this attempts to measure what borrowers and lenders believe to be the real interest rate upon which they are agreeing. One might think of this as the planned real interest rate. To measure the actual impact on the economy of the real interest rate, I believe it is useful to concentrate on the actual burden of interest in terms of lost purchasing power. Thus, I also measure the real interest rates by subtracting the actual inflation rate in each quarter from the nominal interest rate. One might think of this as the experienced real interest rate. The inflation rate used in the appendix and throughout this book when identifying the real interest rate is the rate of increase in the GDP implicit price deflator unless otherwise noted. I choose this over the better-known consumer price index because we are looking for the generalized impact of inflation on interest rates throughout the entire economy, not just on consumers. It should be noted that no matter which way we attempt to measure real interest rates, there will always be limitations. Every individual experiences inflation differently because each person buys different types of products and “sells” different types of products, all of whose prices are changing at different rates than the average, no matter how that average is measured.

Both versions of the real interest rate peaked in 1981, fell during the recession, and then rose in 1984 as the Fed demonstrated its commitment to keeping inflation in check long before unemployment got anywhere near the 1980s version of the “natural” rate—6 percent. See tables W-2 and W-3 at the web site for details, <mars.wnec.edu/~econ/surrender>.

20. Bartley, The Seven Fat Years, 145; Greider, The Secrets of the Temple, 155–80.

21. A supply curve plots alternative prices against the quantities of the good or service businesses are willing and able to provide based on the scarcity of the resources involved. If the true scarcity of all resources used in a production process, including some, such as air and water, that aren’t bought by the producers, is accurately reflected in the costs to the businesses, we can say that the supply curve accurately measures the sacrifice made by society in producing the various quantities of that product. The demand curve plots alternative prices against the quantities of a good or service consumers are willing and able to purchase. If the true satisfaction derived by the consumer is accurately reflected in the price he/she is willing and able to pay, and if there are no spillover costs and/or benefits to noninvolved consumers, then we can say that the demand curve accurately measures the satisfaction experienced by society in consuming the various quantities of that product. Note that the “ifs” about true scarcities and absence of externalities conceal a whole host of exceptions, as even the Reagan administration’s first Council of Economic Advisers acknowledged (see pp. 39–41). For supply-and-demand curves, see any textbook on the principles of economics. For example, Mankiw, Principles of Economics, chap. 4, and Stiglitz, Economics, chap. 4, devote entire chapters to introducing these concepts.

22. A minimum wage does not permit the price to fall to its equilibrium. This deprives some of the “suppliers” (in this case workers) of the opportunity to offer their labor for sale at a wage they would be willing to accept. It also deprives some “consumers” (in this case businesses seeking to hire workers) of the ability to purchase some wage-labor at a wage they would be willing to pay. The result is an artificial reduction in the amount of labor hired and, therefore, a reduction in output. This was the major argument developed by the members of Congress, such as Majority Leader Richard Armey, himself a Ph.D. economist, against the recent increase in the minimum wage.

Table N-5 is an imagined table of alternative wages and quantities of labor offered for sale restaurants by workers and desired to be hired by businesses (the “quantity” is measured in person-hours per week). Let us assume this labor market refers to fast-food restaurants, a typical job for low-wage workers. If the minimum wage were to be set at $5.50 per hour or higher, a significant number of individuals will attempt to find work and will either be hired for fewer hours than they want or will not be hired at all. Only at the “market wage” of $5.00 an hour in this imaginary example will all workers who want to work at that wage find work. Raising that wage to $6.00 per hour would cause businesses to cut back hiring from six hundred hours a week to five hundred hours, thereby causing some people to lose their jobs. For two textbook treatments of the minimum wage, see Mankiw, Principles of Economics, 118–20, and Stiglitz, Economics, 828, 833.

23. Greider, Secrets of the Temple, 177.

24. Bartley, The Seven Fat Years, 224.

25. ERP 1982, 23.