Today’s Madrid is upbeat and vibrant. You’ll feel it. Look around, just about everyone has a twinkle in their eyes.

Madrid is the hub of Spain. This modern capital—Europe’s second-highest, at more than 2,000 feet above sea level—is home to more than 3 million people, with about 6 million living in greater Madrid.

Like its population, the city is relatively young. In medieval times, it was just another village, wedged between the powerful kingdoms of Castile and Aragon. When newlyweds Ferdinand and Isabel united those kingdoms (in 1469), Madrid—sitting at the center of Spain—became the focal point of a budding nation. By 1561, Spain ruled the world’s most powerful empire, and King Philip II moved his capital from tiny Toledo to spacious Madrid. Successive kings transformed the city into a European capital. By 1900, Madrid had 575,000 people, concentrated within a small area. In the mid-20th century, the city exploded with migrants from the countryside, creating today’s modern sprawl. Fortunately for tourists, the historic core survives intact and is easy to navigate.

Madrid is working hard to make itself more livable. Massive urban-improvement projects such as pedestrianized streets, parks, commuter lines, and Metro stations are transforming the city. The investment is making once-dodgy neighborhoods safe and turning ramshackle zones into trendy ones. The broken concrete and traffic chaos of Madrid’s not-so-distant past are gone. Even with Spain’s financial woes, funding for the upkeep of this great city center has been maintained. Madrid feels orderly and welcoming.

Dive headlong into the grandeur and intimate charm of Madrid. Feel the vibe in Puerta del Sol, the pulsing heart of modern Madrid and of Spain itself. The lavish Royal Palace, with its gilded rooms and frescoed ceilings, rivals Versailles. The Prado has Europe’s top collection of paintings, and nearby hangs Picasso’s chilling masterpiece, Guernica. Retiro Park invites you to take a shady siesta and hopscotch through a mosaic of lovers, families, skateboarders, pets walking their masters, and expert bench-sitters. Save time for Madrid’s elegant shops and people-friendly pedestrian zones. On Sundays, cheer for the bull at a bullfight or bargain like mad at a megasize flea market. Swelter through the hot, hot summers or bundle up for the cold winters. Save some energy for after dark, when Madrileños pack the streets for an evening paseo that can continue past midnight. Lively Madrid has enough street-singing, bar-hopping, and people-watching vitality to give any visitor a boost of youth.

Madrid is worth two days and three nights on even the fastest trip. Divide your time among the city’s top three attractions: the Royal Palace (worth a half-day), the Prado Museum (also worth a half-day), and the contemporary bar-hopping scene.

For good day-trip possibilities from Madrid, see the next two chapters (Northwest of Madrid and Toledo).

Morning: Take a brisk, 20-minute good-morning-Madrid walk along the pedestrianized Calle de las Huertas from Puerta del Sol to the Prado. Spend the rest of the morning at the Prado (reserve in advance).

Afternoon: Enjoy an afternoon siesta in Retiro Park. Then tackle modern art at the Reina Sofía, which displays Picasso’s Guernica (closed Tue). Ride bus #27 from this area out through Madrid’s modern section to Puerta de Europa for a dose of the nontouristy, no-nonsense big city.

Evening: End your day with a progressive tapas dinner at a series of characteristic bars.

Morning: Follow my self-guided walk, which loops to and from Puerta del Sol, with a tour through the Royal Palace in the middle.

Afternoon: Your afternoon is free for other sights or shopping. Be out at the magic hour—just before sunset—for the evening paseo when beautifully lit people fill Madrid.

Evening: Take in a flamenco or zarzuela performance.

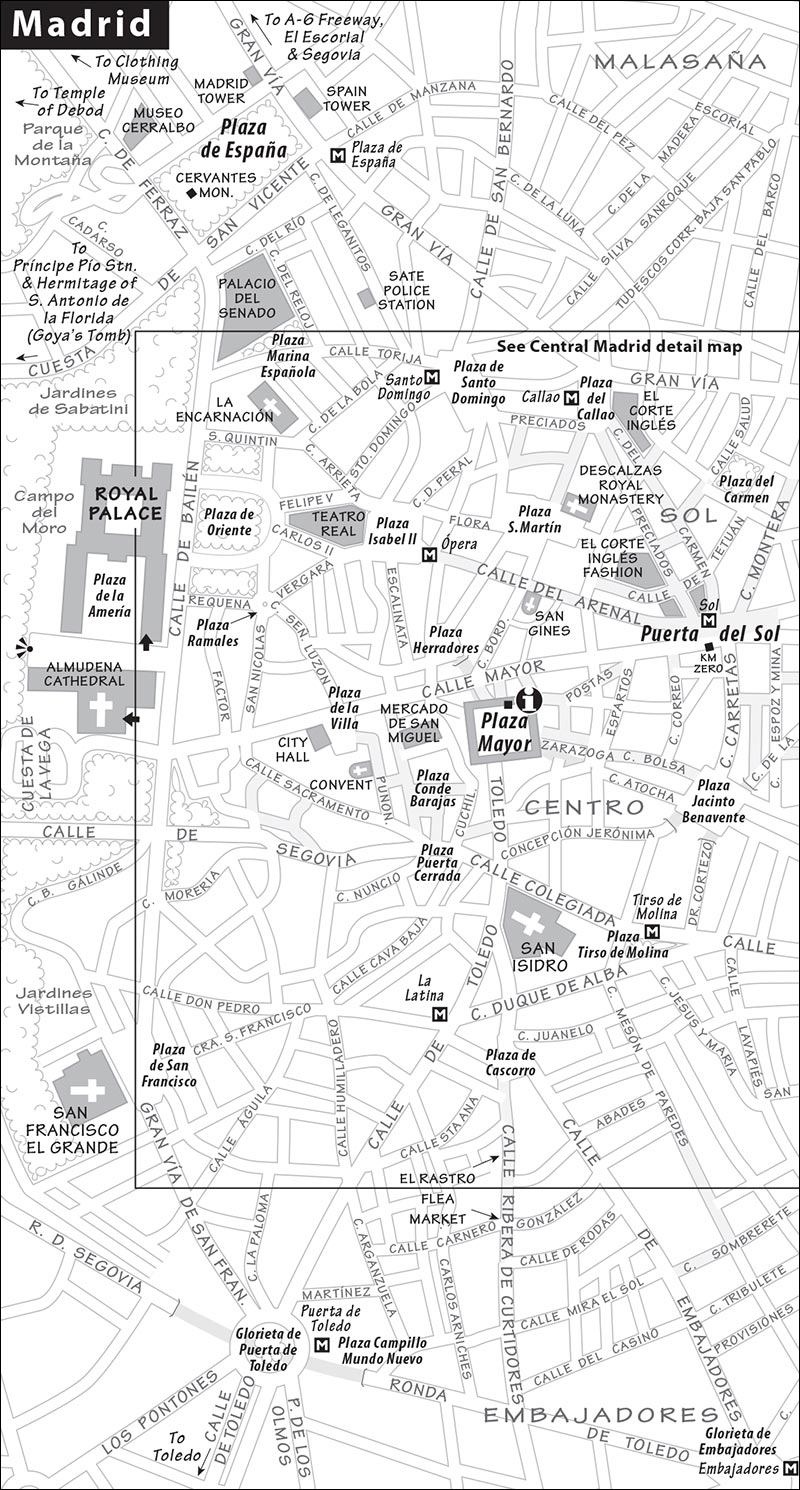

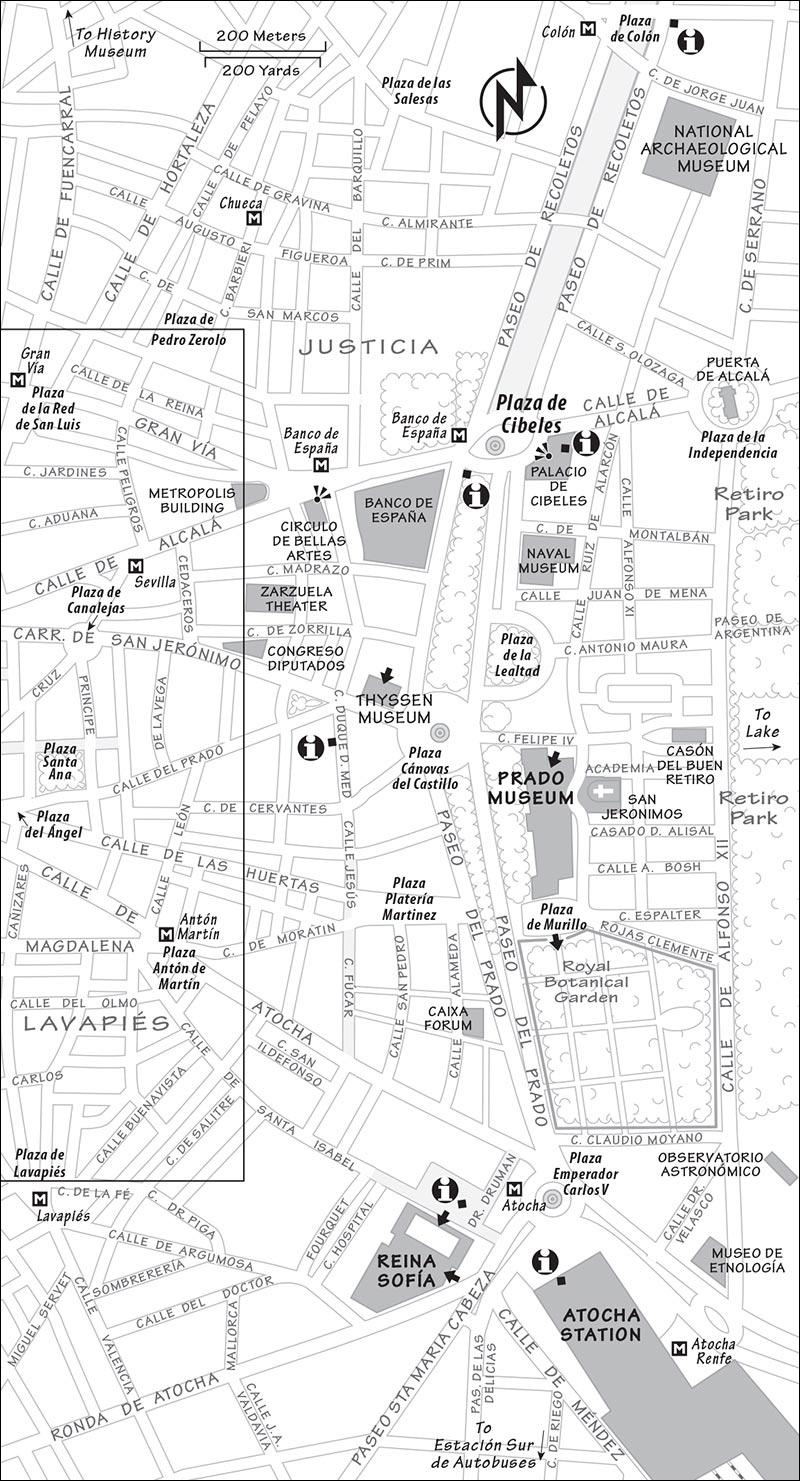

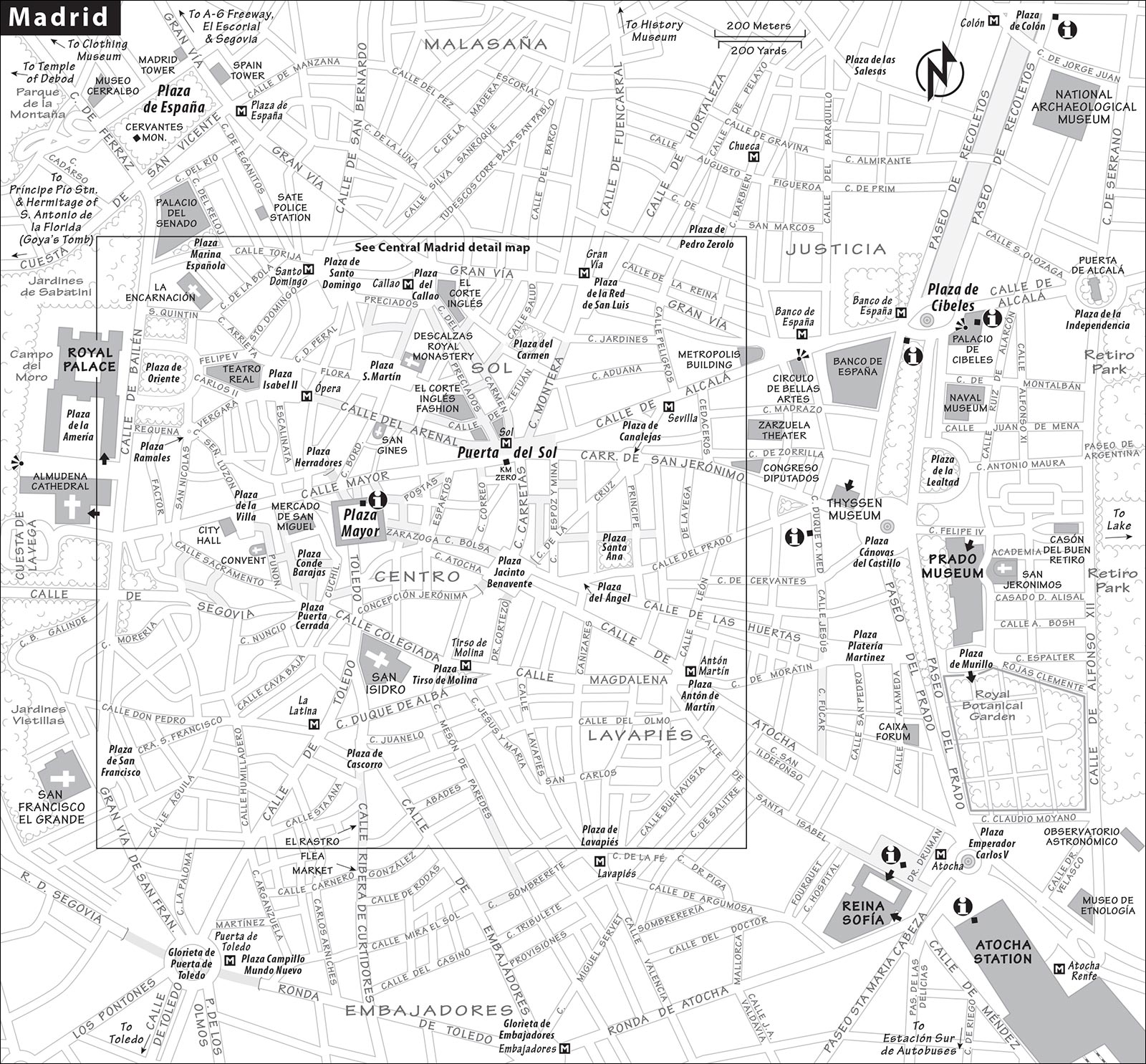

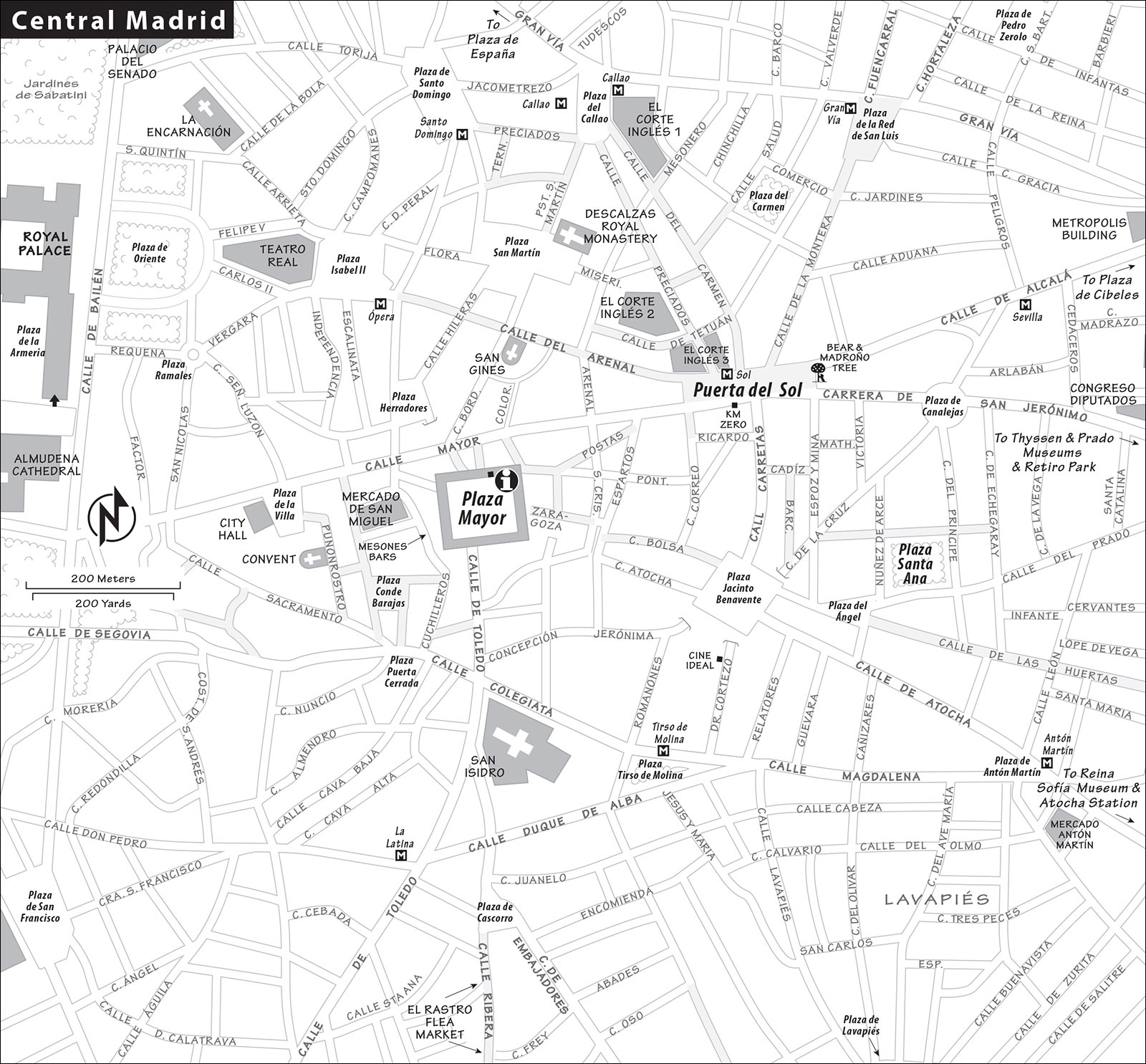

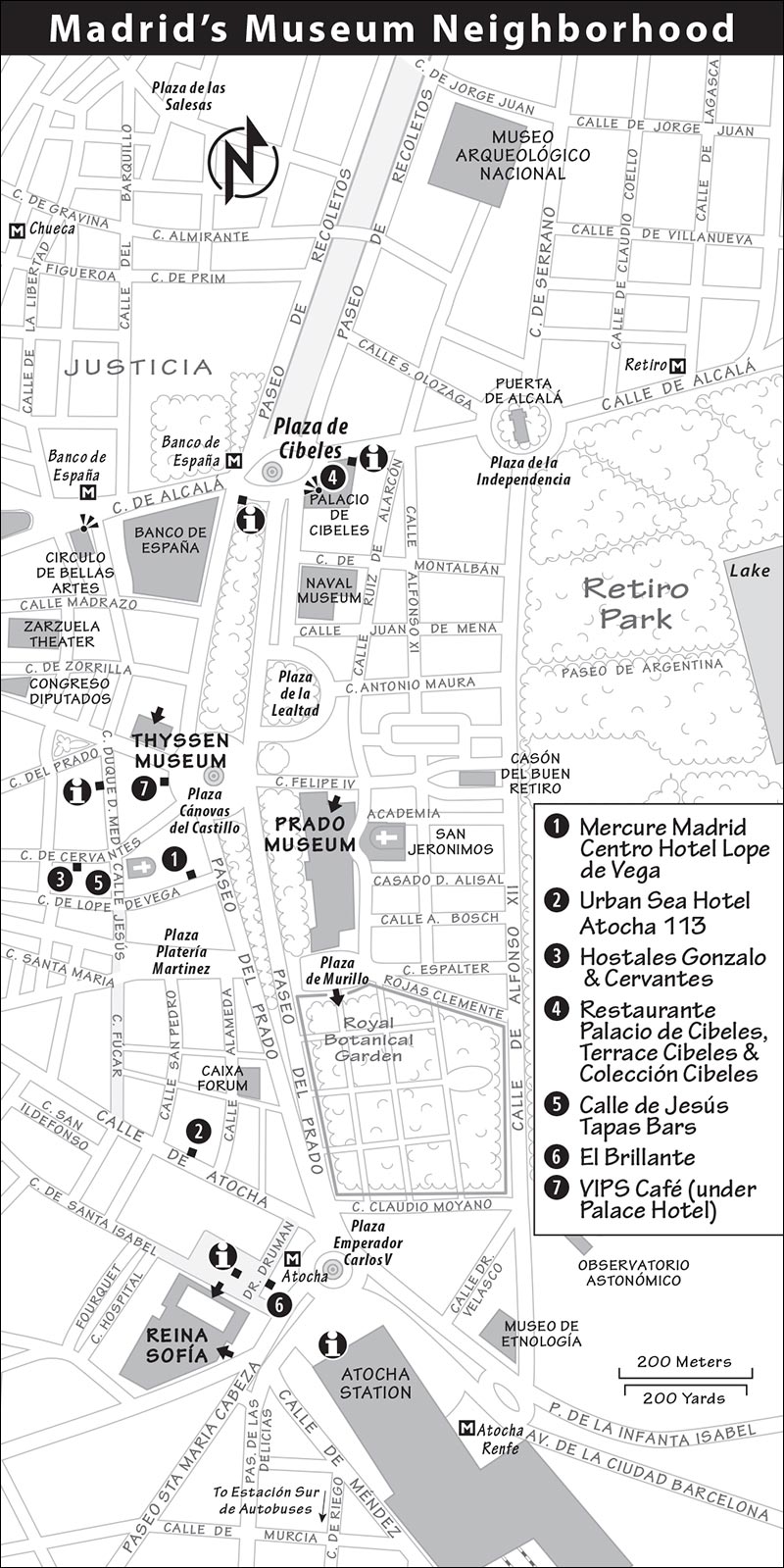

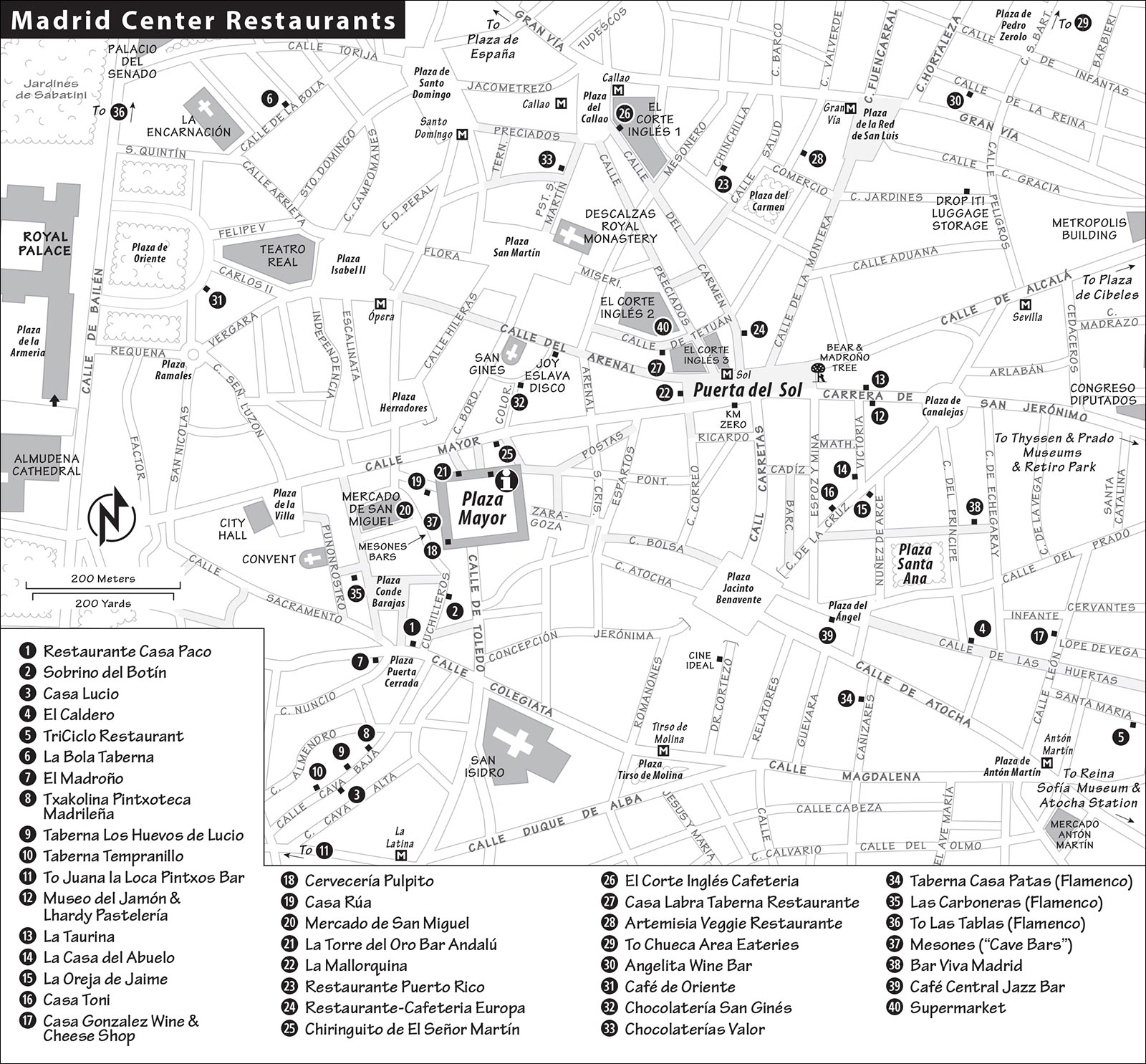

Puerta del Sol marks the center of Madrid. No major sight is more than a 20-minute walk or a €7 taxi ride from this central square. Get out your map and frame off Madrid’s historic core: To the west of Puerta del Sol is the Royal Palace. To the east, you’ll find the Prado Museum, along with the Reina Sofía museum. North of Puerta del Sol is Gran Vía, a broad east-west boulevard bubbling with shops and cinemas. Between Gran Vía and Puerta del Sol is a lively pedestrian shopping zone. And southwest of Puerta del Sol is Plaza Mayor, the center of a 17th-century, slow-down-and-smell-the-cobbles district.

This entire historic core around Puerta del Sol—Gran Vía, Plaza Mayor, the Prado, and the Royal Palace—is easily covered on foot. A wonderful chain of pedestrian streets crosses the city east to west, from the Prado to Plaza Mayor (along Calle de las Huertas) and from Puerta del Sol to the Royal Palace (on Calle del Arenal). Stretching north from Gran Vía, Calle de Fuencarral is a trendy shopping and strolling pedestrian street.

Madrid offers city TIs run by the Madrid City Council, and regional TIs run by the privately owned Turismo Madrid. Both are helpful, but you’ll get more biased information from Turismo Madrid.

City-run TIs share a website (www.esmadrid.com), a central phone number (tel. 914-544-410), and hours (daily 9:30-20:30 or later); exceptions are noted in the listings below. The best and most central city TI is on Plaza Mayor. They can help direct travelers to the nearby foreign tourist assistance office (SATE; see “Helpful Hints” for details).

Madrid’s other city-run TIs are at Plaza de Colón (in the underground passage accessed from Paseo de la Castellana and Calle de Goya), Palacio de Cibeles (inside, up the stairs, and to the right), Plaza de Cibeles (at Paseo del Prado), and Paseo del Arte (on Plaza Sánchez Bustillo, near the Reina Sofía museum). Small TIs inside funky little glass buildings are scattered throughout the city in busy tourist spots, such as at the Reina Sofía’s modern entrance, near the Neptune Fountain and Prado Museum, and on Plaza Callao. Travelers will find city TIs at the airport (Terminals 2 and 4, daily 9:00-20:00).

Regional Turismo Madrid TIs share a website (www.turismomadrid.es) and are located near the Prado Museum (Duque de Medinaceli, across from Palace Hotel, Mon-Sat 8:00-15:00, Sun 9:00-14:00), Chamartín train station (near track 20, Mon-Sat 8:00-20:00, Sun 9:00-14:00), and Atocha train station (AVE arrivals side, Mon-Sat 8:00-20:00, Sun 9:00-20:00). There are also regional TIs at the airport (Terminals 1 and 4, Mon-Sat 9:00-20:00, Sun 9:00-14:00).

At most TIs, you can get the Es Madrid English-language monthly, which lists events around town. Pick up and use the free Metro map and the separate Public Transport map (which includes detailed bus transportation routes throughout the city center).

Entertainment Guides: For arts and culture listings, the TI’s printed material is pretty good, but you can also pick up the more practical Spanish-language weekly entertainment guide Guía del Ocio (€1, sold at newsstands) or visit www.guiadelocio.com. It lists daily live music (“Conciertos”), museums (under “Arte”—with the latest times, prices, and special exhibits), restaurants (an exhaustive listing), TV schedules, and movies (“V.O.” means original version, “V.O. en inglés sub” means a movie is played in English with Spanish subtitles rather than dubbed).

For more information on arriving at or departing from Madrid, see “Madrid Connections,” at the end of this chapter.

By Train: Madrid’s two train stations, Chamartín and Atocha, are both on Metro and cercanías (suburban train) lines with easy access to downtown Madrid. Chamartín handles most international trains and the AVE (AH-vay) train to and from Segovia. Atocha generally covers southern Spain, as well as the AVE trains to and from Barcelona, Córdoba, Sevilla, and Toledo. Many train tickets include a cercanías connection to or from the train station.

Traveling Between Chamartín and Atocha Stations: You can take the Metro (line 1, 30-40 minutes, €1.50, but the cercanías trains are faster (6/hour, 13 minutes, Atocha-Chamartín lines C1, C3, C4, C7, C8, and C10 each connect the two stations, lines C3 and C4 also stop at Sol—Madrid’s central square, €1.70). If you have a rail pass or any regular train ticket to Madrid, you can get a free transfer. Go to the Cercanías touch-screen ticket machine and choose combinado cercanías, then either scan the bar code of your train ticket or punch in a code (labeled combinado cercanías), and choose your destination. These trains depart from Atocha’s track 6 and generally Chamartín’s track 1, 3, 8, or 9—but check the Salidas Inmediatas board to be sure.

By Bus: Madrid has several bus stations, each one handy to a Metro station: Estación Sur de Autobuses (for Ávila, Salamanca, and Granada; Metro: Méndez Álvaro); Plaza Elíptica (for Toledo, Metro: Plaza Elíptica); Moncloa (for El Escorial, Metro: Moncloa); and Avenida de América (for Pamplona and Burgos, Metro: Avenida de América). If you take a taxi from the station to your hotel, you’ll pay a €3 supplement.

By Plane: Both international and domestic flights arrive at Madrid’s Barajas Airport. Options for getting into town include public bus, cercanías train, Metro, taxi, and minibus shuttle.

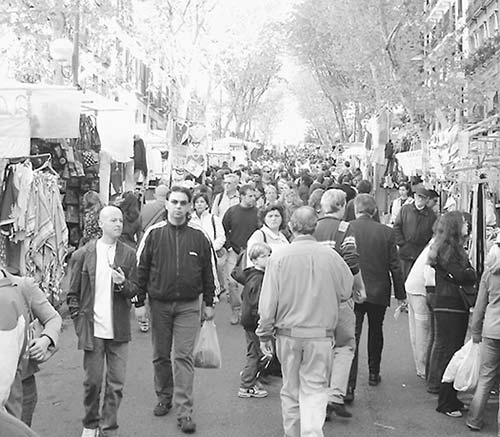

Sightseeing Tips: While the Prado and palace are open daily, the Reina Sofía (with Picasso’s Guernica) is closed on Tuesday, and other sights are closed on Monday, including the Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial, outside of Madrid (see next chapter). If you’re here on a Sunday, consider going to the flea market (year-round) and/or a bullfight (some Sun in March-mid-Oct; generally daily during San Isidro festival in May-early June).

Theft Alert: Be wary of pickpockets—anywhere, anytime. Areas of particular risk are Puerta del Sol (the central square), El Rastro (the flea market), Gran Vía (the paseo zone: Plaza del Callao to Plaza de España), the Ópera Metro station (or anywhere on the Metro), bus #27, the airport, and any crowded street. Be alert to the people around you: Someone wearing a heavy jacket in the summer is likely a pickpocket. Teenagers may dress like Americans and work the areas around the three big art museums; being under 18, they can’t be charged in any meaningful way by the police. Assume any fight or commotion is a scam to distract people about to become victims of a pickpocket. Wear your money belt. For help if you get ripped off, see the next listing.

Tourist Emergency Aid: SATE is an assistance service for tourists who might need, for any reason, to visit a police station or lodge a complaint. Help ranges from canceling stolen credit cards to assistance in reporting a crime (central police station, daily 9:00-24:00, near Plaza de Santo Domingo at Calle Leganitos 19). They can help you get to the police station and will even act as an interpreter if you have trouble communicating with the police. Or you can call in your report to the SATE line (24-hour tel. 902-102-112, English spoken once you get connected to a person), then go to the police station (where they’ll likely speak only Spanish) to sign your statement.

You may see a police station in the Sol Metro station.

Prostitution: Diverse by European standards, Madrid is spilling over with immigrants from South America, North Africa, and Eastern Europe. Many young women come here, fall on hard times, and end up on the streets. While it’s illegal to make money from someone else selling sex (i.e., pimping), prostitutes over 18 can solicit legally. Calle de la Montera (leading from Puerta del Sol to Plaza Red de San Luis) is lined with what looks like a bunch of high-school girls skipping out of school for a cigarette break. Don’t stray north of Gran Vía around Calle de la Luna and Plaza Santa María Soledad—while the streets may look inviting, this area is a meat-eating flower.

One-Stop Shopping at El Corte Inglés: Madrid’s dominant department store is El Corte Inglés, filling three huge buildings in the commercial pedestrian zone just off Puerta del Sol. Building 3—full of sports equipment, books, and home furnishings—is closest to the Puerta del Sol. Building 2, a block up from Puerta del Sol on Calle Preciados, has a handy info desk at the door (with Madrid maps), a travel agency/box office for local events, souvenirs, toiletries, a post office, men and women’s fashion, a boring cafeteria, and a vast supermarket in the basement with a fancy “Club del Gourmet” section for edible souvenirs. Farther north on Calle del Carmen toward Plaza del Callao is Building 1, which has electronics, another travel agency/box office, and the “Gourmet Experience”—a floor filled with fun eateries and a rooftop terrace for diners.

All El Corte Inglés department stores are open daily (Mon-Sat 10:00-22:00, Sun 11:00-21:00, tel. 913-798-000, www.elcorteingles.es). Locals figure you’ll find anything you need at El Corte Inglés. Salespeople wear flag pins indicating which languages they speak. If doing serious shopping here, ask about their discounts (10 percent for tourists) and VAT refund policy (21 percent but with a minimum purchase requirement that you can accumulate over multiple shopping trips).

Wi-Fi: Plaza Mayor has free Wi-Fi, as does the Palacio de Cibeles and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum. You can get online on all Madrid buses and trains—look for Wi-Fi gratis signs.

Bookstores: For books in English, try FNAC Callao (Calle Preciados 28, tel. 902-100-632), Casa del Libro (English on basement floor, Gran Vía 29, tel. 902-026-402), and El Corte Inglés (guidebooks and some fiction, in its Building 3 Books/Librería branch kitty-corner from main store, fronting Puerta del Sol—see listing above).

Laundry: For a self-service laundry, try Colada Express at Calle Campomanes 9 (free Wi-Fi, daily 9:00-22:00, tel. 657-876-464) or Lavandería at Calle León 6 (self-service, Mon-Sat 9:00-22:00, Sun 12:00-15:00; full-service, Mon-Sat 9:00-14:00 & 15:00-20:00, tel. 914-299-545).

Travel Agencies: The grand department store El Corte Inglés has two travel agencies (air and rail tickets, but not reservations for rail-pass holders, €2 fee; Building 2—first floor, Building 1—third floor; see “One-Stop Shopping at El Corte Inglés,” earlier). They also have a travel agency in the Atocha train station. These are fast and easy places to buy AVE and other train tickets.

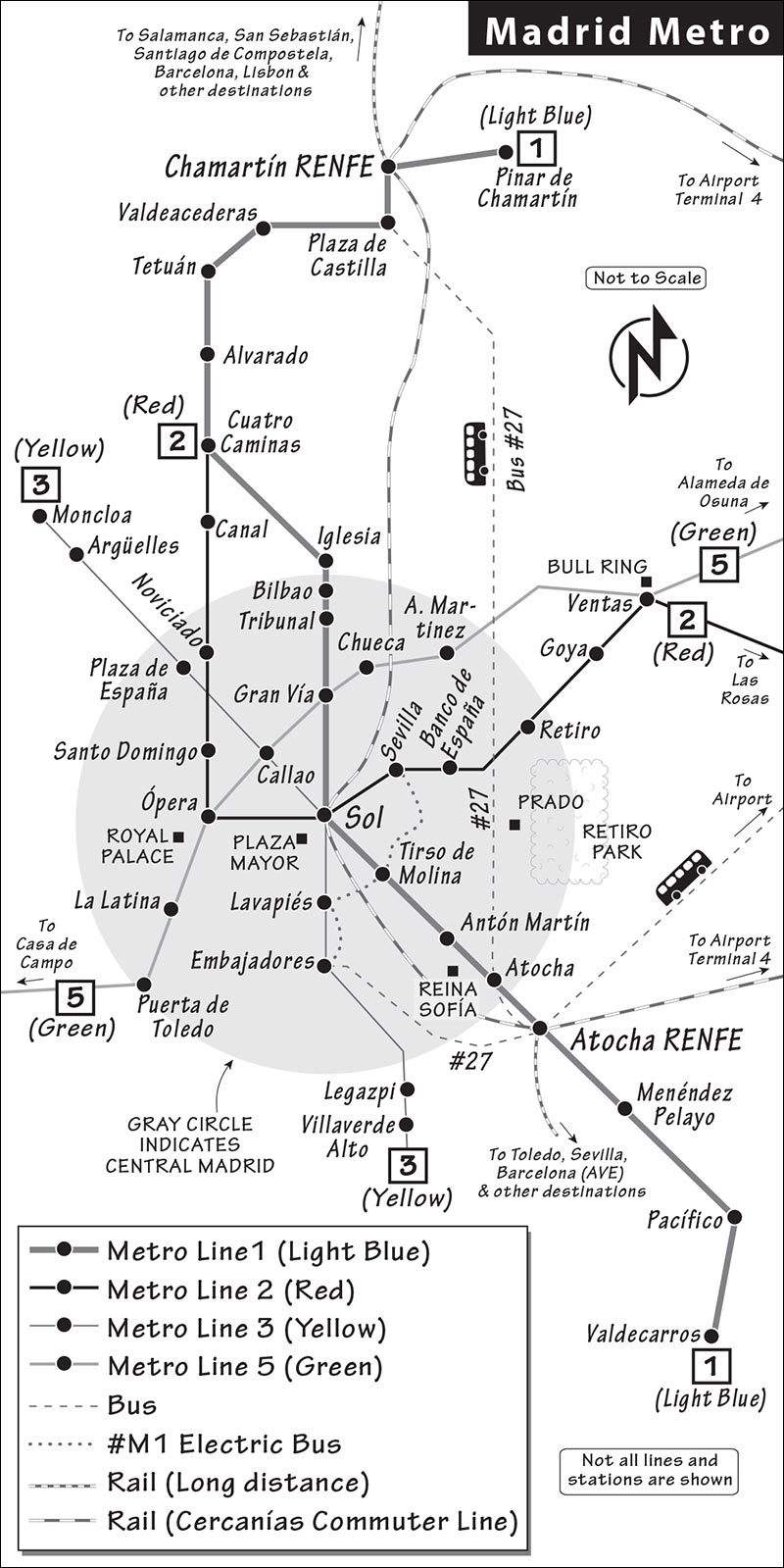

Madrid has excellent public transit. Pick up the Metro map (free, available at TIs or at Metro info booths in stations with staff); for buses get the fine Public Transport map (free at TIs). The metropolitan Madrid transit website (www.crtm.es) covers all public transportation options (Metro, bus, and suburban rail).

By Metro: The city’s broad streets can be hot and exhausting. A subway trip of even a stop or two saves time and energy. Madrid’s Metro is simple, speedy, and cheap. It costs €1.50 for a ride within zone A, which covers most of the city, but not trains out to the airport. The 10-ride, €12.20 Metrobus ticket can be shared by several travelers with the same destination and works on both the Metro and buses. Buy single-ride tickets in the Metro (from easy-to-use machines or ticket booths—just pick your destination from the alphabetized list and follow the simple prompts), at newspaper stands, or at Estanco tobacco shops. Insert your ticket in the turnstile, then retrieve it and pass through. The Metro runs from 6:00 to 1:30 in the morning. At all times, be alert to thieves, who thrive in crowded stations.

Study your Metro map—the simplified map on the previous page can get you started. Lines are color-coded and numbered; use end-of-the-line station names to choose your direction of travel. Once in the Metro station, signs direct you to the train line and direction (e.g., Linea 1, Valdecarros). To transfer, follow signs in the station leading to connecting lines. Once you reach your final stop, look for the green salida signs pointing to the exits. Use the helpful neighborhood maps to choose the right salida and save yourself lots of walking. Metro info: www.metromadrid.es.

By Bus: City buses, though not as easy as the Metro, can be useful (€1.50 tickets sold on bus, €12.20 for a 10-ride Metrobus ticket, bus maps at TI or info booth on Puerta del Sol, poster-size maps usually posted at bus stops, buses run 6:00-24:00, much less frequent Buho buses run all night). The EMT Madrid app finds the closest stops and lines and gives accurate wait times, plus there’s a version in English. Bus info: www.emtmadrid.es.

By Taxi or Uber: Madrid’s 15,000 taxis are reasonably priced and easy to hail. A green light on the roof indicates that a taxi is available. Foursomes travel as cheaply by taxi as by Metro. For example, a ride from the Royal Palace to the Prado costs about €7. After the drop charge (about €3), the per-kilometer rate depends on the time: Tarifa 1 (€1.05/kilometer) is charged Mon-Fri 7:00-21:00; Tarifa 2 (€1.20/kilometer) is valid after 21:00 and on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays. If your cabbie uses anything other than Tarifa 1 on weekdays (shown as an isolated “1” on the meter), you’re being cheated.

Rates can be higher if you go outside Madrid. There’s a flat rate of €30 between the city center and any one of the airport terminals. Other legitimate charges include the €3 supplement for leaving any train or bus station, €20 per hour for waiting, and a maximum of €5 if you call to have the taxi come to you. Make sure the meter is turned on as soon as you get into the cab so the driver can’t tack anything onto the official rate. If the driver starts adding up “extras,” look for the sticker detailing all legitimate surcharges (which should be on the passenger window).

Madrid is the only city in Spain where Uber operates, and prices are generally similar to taxis.

To sightsee on your own, download my free Madrid audio tour.

To sightsee on your own, download my free Madrid audio tour.

Letango Tours offers private tours, packages, and stays all over Spain with a focus on families and groups. Carlos Galvin, a Spaniard who led tours for my groups for more than a decade, his wife Jennifer from Seattle, and their team of guides in Madrid offer a kid-friendly “Madrid Discoveries” tour that mixes a market walk and history with a culinary-and-tapas introduction (€275/group, up to 5 people, kids free, 3-plus hours). They also lead tours to Barcelona, whitewashed villages, wine country, and more (www.letango.com, tours@letango.com).

At Madridivine, David Gillison enthusiastically shares his love for his adopted city through food and walking tours of historic Madrid. He connects you with locals, food, and wine from an insider’s viewpoint (€200/group, up to 7 people, 3-hour tour, food and drinks extra—usually around €35-40, www.madridivine.com/ricksteves, madridivineinfo@gmail.com).

Julià Travel offers various walking and food tours, including one on Hapsburg Madrid and another that allows you to skip the line at the Prado (from €28, www.juliatravel.com). See Julià Travel’s listing under “On Wheels,” below, for info about their bus tours.

Frederico and Cristina, along with their team, are licensed guides who lead city walks. Frederico specializes in family tours of Madrid and engaging kids and teens in museums, and Cristina excels at intertwining history and art (prices per group: €160/2 hours, €200/4 hours, €240/6 hours). They also lead tours to nearby towns (with public or private transit, mobile 649-936-222, www.spainfred.com, info@spainfred.com).

Across Madrid is run by Almudena Cros, a well-travelled academic Madrileña. She offers several specialized tours including one on the Spanish Civil War that draws on her family’s history. She also gives a good Prado tour for kids (generally €70/person, maximum 8 people, €50 extra for private tour, book well in advance, mobile 652-576-423, www.acrossmadrid.com, info@acrossmadrid.com).

Stephen Drake-Jones, an eccentric British expat, has led walks of historic old Madrid almost daily for decades. A historian with a passion for the Duke of Wellington (the general who stopped Napoleon), Stephen loves to teach history. For €75 you get a 3.5-hour tour with three stops for drinks and tapas (call it lunch; daily at 11:00, maximum 8 people). You can also book a private version of this tour (€190/2 people) or one of his many themed tours (Spanish Civil War, Hemingway’s Madrid, and more; www.wellsoc.org, mobile 609-143-203, chairman@wellsoc.org).

Other good licensed local guides include: Inés Muñiz Martin (guiding since 1997 and a third-generation Madrileña, €120-185/2-5 hours, 25 percent more on weekends and holidays, mobile 629-147-370, www.immguidedtours.com, info@immguidedtours.com), and Susana Jarabo (with a master’s in art history, €200/4 hours; extra charge to tour by bike, scooter, or Segway; available March-Aug, mobile 667-027-722, susanjarabo@yahoo.es).

Madrid City Tour makes two different hop-on, hop-off circuits through the city: historic and modern. Buy a ticket from the driver (€21/1 day, €25/2 consecutive days), and you can hop from sight to sight and route to route as you like, listening to a recorded English commentary along the way (15-21 stops, about 90 minutes, with buses departing every 15 minutes). The two routes intersect at the south side of Puerta del Sol and in front of Starbucks across from the Prado (daily March-Oct 9:30-22:00, Nov-Feb 10:00-18:00, tel. 917-791-888, www.madridcitytour.es).

Julià Travel leads bus tours departing from Calle San Nicolás near Plaza de Ramales, just south of Plaza de Oriente (office open Mon-Fri 8:00-19:00, Sat-Sun 8:00-15:00, tel. 915-599-605). Their city offerings include a 2.5-hour Madrid tour with a live guide in two or three languages (€27, one stop for a drink at Hard Rock Café, one shopping stop, no museum visits, daily at 9:00 and 15:00, no reservation required—just show up 15 minutes before departure). See their website for other tours and services (www.juliatravel.com).

A ride on public bus #27 from the museum neighborhood up Paseo del Prado and Paseo de la Castellana to the Puerta de Europa and back gives visitors a glimpse of the modern side of Madrid, while a ride on electric minibus #M1 takes you through the characteristic, gritty old center.

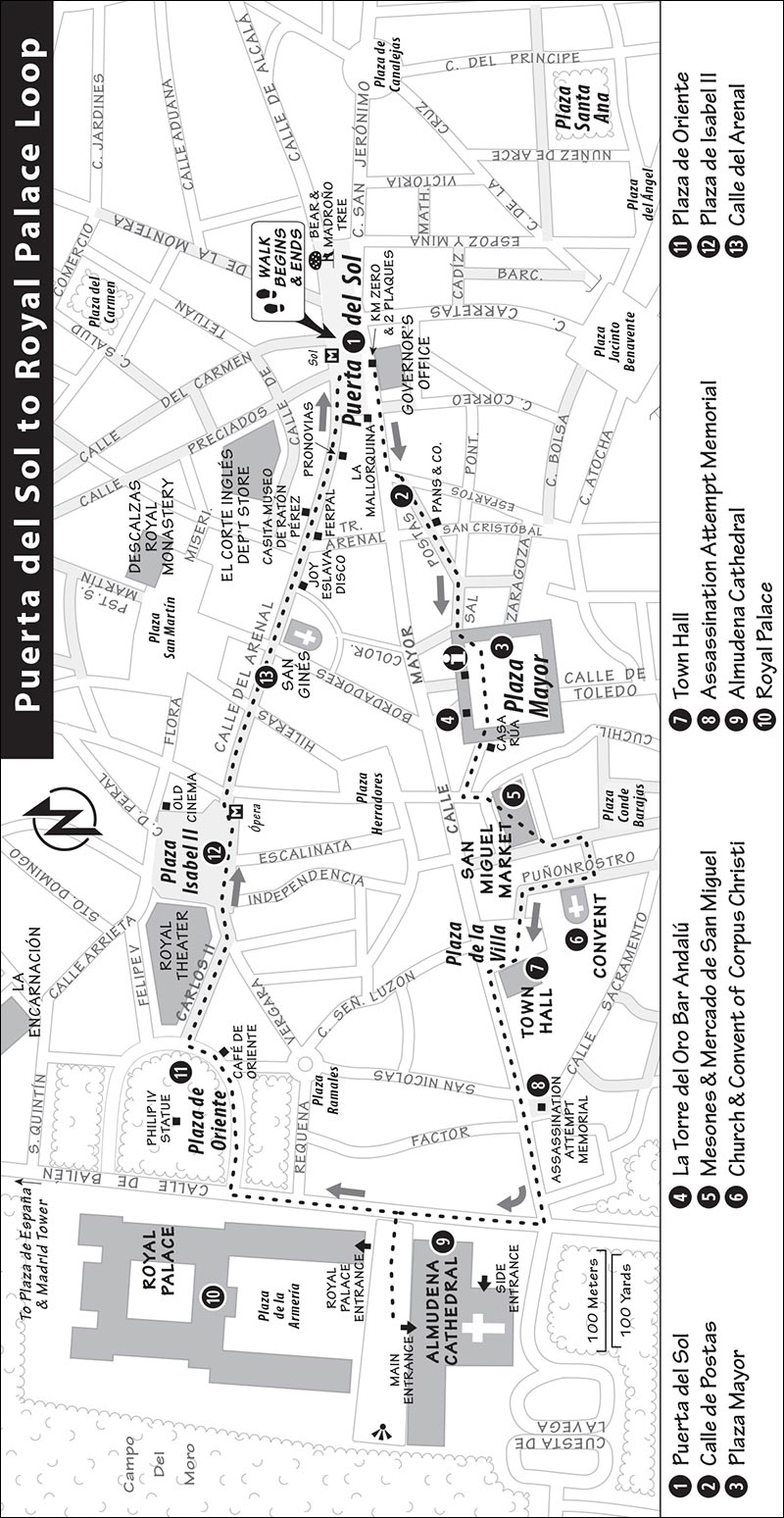

Two self-guided walks provide a look at two different sides of Madrid. For a taste of old Madrid, start with my “Puerta del Sol to Royal Palace Loop,” which winds through the historic center. My “Gran Vía Walk” lets you glimpse a more modern side of Spain’s capital.

Download my free Madrid audio tour, which complements this section.

Download my free Madrid audio tour, which complements this section.

Madrid’s historic center is pedestrian-friendly and filled with spacious squares, a trendy market, bulls’ heads in a bar, and a cookie-dispensing convent. Allow about two hours for this self-guided, mile-long triangular walk. You’ll start and finish on Madrid’s central square, Puerta del Sol (Metro: Sol).

• Start in the middle of the square, by the equestrian statue of King Charles III, and survey the scene.

The bustling Puerta del Sol, rated ▲▲, is Madrid’s—and Spain’s—center. It’s a hub for the Metro, cercanías (local) trains, revelers, pickpockets, and characters dressed as cartoon characters (who hit up little kids so their parents end up paying for a photo op). You’ll also notice that it’s a meeting point for many “free tours” with their color-coded umbrellas. In recent years, the square has undergone a facelift to become a mostly pedestrianized, wide-open space...without a bench or spot of shade in sight. Nearly traffic-free, it’s a popular site for political demonstrations. Don’t be surprised if you come across a large, peaceful protest here.

The equestrian statue in the middle of the square honors King Charles III (1716-1788) whose enlightened urban policies earned him the affectionate nickname “the best mayor of Madrid.” He decorated the squares with beautiful fountains, got those meddlesome Jesuits out of city government, established the public-school system, mandated underground sewers, opened his private Retiro Park to the general public, built the Prado, made the Royal Palace the wonder of Europe, and generally cleaned up Madrid.

Head to the slightly uphill end of the square and find the statue of a bear pawing a tree—a symbol of Madrid since medieval times. Bears used to live in the royal hunting grounds outside the city. And the madroño trees produce a berry that makes the traditional madroño liqueur.

Charles III faces a red-and-white building with a bell tower. This was Madrid’s first post office, which he founded in the 1760s. Today it’s the county governor’s office, home to the president who governs greater Madrid. The building is notorious for having once been dictator Francisco Franco’s police headquarters. A tragic number of those detained and interrogated by the Franco police tried to “escape” by jumping out its windows to their deaths.

Appreciate the harmonious architecture of the buildings that circle the square—yellow-cream, four stories, balconies of iron, shuttered windows, and balustrades along the rooflines.

Crowds fill the square on New Year’s Eve as the rest of Spain watches the Times Square-style action on TV. The bell atop the governor’s office chimes 12 times, while Madrileños eat one grape for each ring to bring good luck through each of the next 12 months.

• Cross the square and street to the governor’s office.

Look at the curb directly in front of the entrance to the governor’s office. The marker is “kilometer zero,” the symbolic center of Spain (with the country’s six main highways indicated). Standing on the zero marker with your back to the governor’s office, get oriented visually: At twelve o’clock (straight ahead), notice the thriving pedestrian commercial zone (with the huge El Corte Inglés department store). Look up to see the famous Tío Pepe sign—advertising the famous sherry from Andalucía since the 1930s. At two o’clock starts the seedier Calle de la Montera, a street with shady characters and prostitutes that leads to the trendy, pedestrianized Calle de Fuencarral. At three o’clock is the biggest Apple store in Europe; the Prado is about a mile farther to your right. At ten o’clock, the pedestrianized Calle del Arenal Street (which leads to the Royal Palace) dumps into this square...just where you will end this walk.

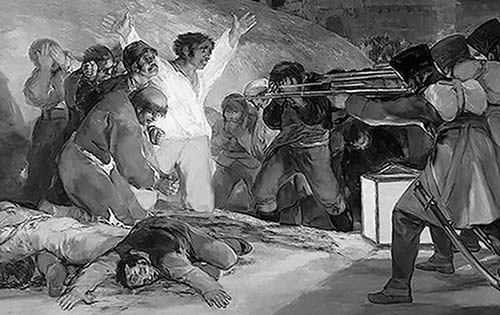

Now turn around. On either side of the entrance to the governor’s office are two white marble plaques tied to important dates, expressing thanks from the regional government to its citizens for assisting in times of dire need. To the left of the entry, a plaque on the wall honors those who helped during the terrorist bombings of March 11, 2004 (we have our 9/11—Spain commemorates its 3/11). A similar plaque on the right marks the spot where the war against Napoleon started in 1808. When Napoleon invaded Spain and tried to appoint his brother (rather than the Spanish heir) as king of Spain, an angry crowd gathered outside this building. The French soldiers attacked and simply massacred the mob. Painter Francisco de Goya, who worked just up the street, observed the event and captured the tragedy in his paintings Second of May, 1808 and Third of May, 1808, now in the Prado.

Finally, notice the hats of the civil guardsmen at the entry. The hats have square backs, and it’s said that they were cleverly designed so that the guards can lean against the wall while enjoying a cigarette.

On the corner of Puerta del Sol and Calle Mayor (downhill end of Puerta del Sol) is the busy, recommended confitería La Mallorquina, “fundada en 1.894.” Go inside for a tempting peek at racks with goodies hot out of the oven. Enjoy observing the churning energy at the bar lined with Madrileños popping in for a fast coffee and a sweet treat. The shop is famous for its cream-filled Napolitana pastry. Or sample Madrid’s answer to doughnuts, rosquillas (tontas means “silly”—plain, and listas means “all dressed up and ready to go”—with icing). The café upstairs is more genteel, with nice views of the square.

From inside the shop, look back toward the entrance and notice the tile above the door with the 18th-century view of Puerta del Sol. Compare this with today’s view out the door. This was before the square was widened, when a church stood at its top end.

Puerta del Sol (“Gate of the Sun”) is named for a long-gone gate with the rising sun carved onto it, which once stood at the eastern edge of the old city. From here, we begin our walk through the historic town that dates back to medieval times.

• Head west on busy Calle Mayor, just past McDonald’s, and veer left up the pedestrian-only street called...

The street sign shows the post coach heading for that famous first post office. Medieval street signs posted on the lower corners of buildings included pictures so the illiterate (and monolingual tourists) could “read” them. Fifty yards up the street on the left, at Calle San Cristóbal, is Pans & Company, a popular Catalan sandwich chain offering lots of healthy choices. While Spaniards tend to consider American fast food unhealthy—both culturally and physically—they love it. McDonald’s and Burger King are thriving in Spain.

• Continue up Calle de Postas, and take a slight right on Calle de la Sal through the arcade, where you emerge into...

This square, worth ▲▲, is a vast, cobbled, traffic-free chunk of 17th-century Spain. In early modern times, this was Madrid’s main square. The equestrian statue (wearing a ruffled collar) honors Philip III, who (in 1619) transformed the old marketplace into a Baroque plaza. The square is 140 yards long and 100 yards wide, enclosed by three-story buildings with symmetrical windows, balconies, slate roofs, and steepled towers. Each side of the square is uniform, as if a grand palace were turned inside-out. This distinct “look,” pioneered by architect Juan de Herrera (who finished El Escorial), is found all over Madrid.

This site served as the city’s 17th-century open-air theater. Upon this stage, much Spanish history has been played out: bullfights, fires, royal pageantry, and events of the gruesome Inquisition. Worn-down reliefs on the seatbacks under the lampposts illustrate the story. During the Inquisition, many were tried here—suspected heretics, Protestants, Jews, tour guides without a local license, and Muslims whose “conversion” to Christianity was dubious. The guilty were paraded around the square before their executions, wearing billboards listing their many sins (bleachers were built for bigger audiences, while the wealthy rented balconies). The heretics were burned, and later, criminals were slowly strangled as they held a crucifix, hearing the reassuring words of a priest as the life was squeezed out of them with a garrote. Up to 50,000 people could crowd into this square for such spectacles.

The square’s buildings are mainly private apartments. Want one? Costs run from €400,000 for a tiny attic studio to €2 million and up for a 2,500-square-foot flat. The square is painted a democratic shade of burgundy—the result of a citywide vote. Since the end of decades of dictatorship in 1975, there’s been a passion for voting here. Three different colors were painted as samples on the walls of this square, and the city voted for its favorite.

The building to Philip’s left, on the north side beneath the twin towers, was once home to the baker’s guild and now houses the TI, which is wonderfully air-conditioned.

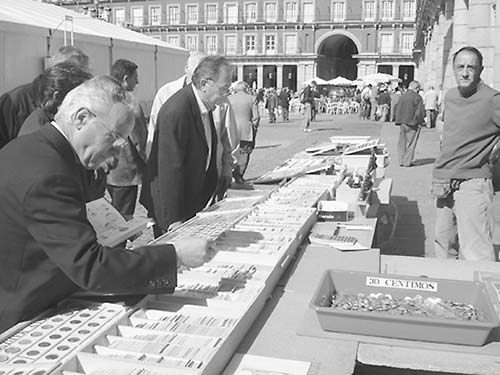

A stamp-and-coin market bustles at Plaza Mayor on Sundays (10:00-14:00). Day or night, Plaza Mayor is a colorful place to enjoy an affordable cup of coffee or overpriced food. Throughout Spain, lesser plazas mayores provide peaceful pools in the whitewater river of Spanish life. We’ll cross the square, leaving through the far corner on the right-hand side, with a quick stop along that arcade on the way.

For some interesting, if gruesome, bullfighting lore, step into La Torre del Oro Bar Andalú. This bar is a good place to finish off your Plaza Mayor visit (at #26, a few doors to the left of the TI). The bar has Andalú (Andalusian) ambience and an entertaining—if gruff—staff. Warning: They may push expensive tapas on tourists. The price list posted outside the door makes your costs perfectly clear: “barra” indicates the price at the bar; “terraza” is the price at an outdoor table. Step inside, stand at the bar, and order a drink—a caña (small draft beer) shouldn’t cost more than €2.50.

The interior is a temple to bullfighting, festooned with gory decor. Notice the breathtaking action captured in the many photographs. Look under the stuffed head of Barbero the bull (center, facing the bar). At eye level you’ll see a puntilla, the knife used to put poor Barbero out of his misery at the arena. The plaque explains: weight, birth date, owner, date of death, which matador killed him, and the location.

Just to the left of Barbero is a photo of longtime dictator Franco with the famous bullfighter Manuel Benítez Pérez—better known as El Cordobés, the Elvis of bullfighters and a working-class hero.

At the top of the stairs going down to the WC, find the photo of El Cordobés and Robert Kennedy—looking like brothers. Three feet to the left of them (and elsewhere in the bar) is a shot of Che Guevara enjoying a bullfight.

Below and left of the Kennedy photo is a picture of El Cordobés’ illegitimate son being gored. Disowned by El Cordobés senior, yet still using his dad’s famous name after a court battle, the junior El Cordobés is one of this generation’s top fighters.

At the end of the bar, in a glass case, is the “suit of lights” the great El Cordobés wore in an ill-fated 1967 fight, in which the bull gored him. El Cordobés survived; the bull didn’t. Find the photo of Franco with El Cordobés at the far end, to the left of Segador the bull.

In the case with the “suit of lights,” notice the photo of a matador (not El Cordobés) horrifyingly hooked by a bull’s horn. For a series of photos showing this episode (and the same matador healed afterward), look to the right of Barbero back by the front door.

Below that series is a strip of photos showing José Tomás—a hero of this generation (with the cute if bloody face)—getting his groin gored. Tomás is renowned for his daring intimacy with the bull’s horns—as illustrated here.

Leaving the bull bar, turn right and notice the La Favorita hat shop (at #25). See the plaque in the pavement honoring the shop, which has served the public since 1894.

Consider taking a break at one of the tables on Madrid’s grandest square. Cafetería Margerit (nearby) occupies Plaza Mayor’s sunniest corner and is a good place to enjoy a coffee with the view. The scene is easily worth the extra euro you’ll pay for the drink.

• Leave Plaza Mayor on Calle de Ciudad Rodrigo (at the northwest corner of the square), passing a series of solid turn-of-the-20th-century storefronts and sandwich joints, such as Casa Rúa, famous for their cheap bocadillos de calamares—fried squid rings on a small baguette.

Mistura Ice Cream (across the lane at Ciudad Rodrigo 6) serves fine coffee and quality ice cream, rolling your choice of topping into the ice cream with a cold-stone ritual that locals enjoy. Its cellar is called the “chill zone” for good reason—an oasis of cool and peace, ideal for enjoying your treat.

Emerging from the arcade, turn left and head downhill toward the iron covered market hall. Before entering the market, look downhill to the left down a street called Cava de San Miguel.

Lining the street called Cava de San Miguel is a series of traditional dive bars called mesones. If you like singing, sangria, and sloppy people, come back after 22:00 to visit one. These cave-like bars, stretching far back from the street, get packed with Madrileños out on dates who—emboldened by sangria and the setting—are prone to suddenly breaking out in song. It’s a lowbrow, electric-keyboard, karaoke-type ambience, best on Friday and Saturday nights. The odd shape of these bars isn’t a contrivance for the sake of atmosphere—Plaza Mayor was built on a slope, and these underground vaults are part of a structural system that braces the leveled plaza.

For a much more refined setting, pop into the Mercado de San Miguel (daily 10:00-24:00). This historic iron-and-glass structure from 1916 stands on the site of an even earlier marketplace. Renovated in the 21st century, the city’s oldest surviving market hall now hosts some 30 high-end vendors of fresh produce, gourmet foods, wines by the glass, tapas, and full meals. Locals and tourists alike pause here for its food, natural-light ambience, and social scene.

Go on an edible scavenger hunt by simply grazing down the center aisle. You’ll find: fish tapas, gazpacho and pimientos de Padrón, artisan cheeses, and lots of olives. Skewer them on a toothpick and they’re called banderillas—for the decorated spear a bullfighter thrusts into the bull’s neck. The smallest olives are Campo Real—the Madrid favorite. You’ll find a draft vermut (Vermouth) bar with kegs of the sweet local dessert wine, along with sangria and sherry (V.O.R.S. means, literally, very old rare sherry—dry and full-bodied). Finally, the San Onofre bar is for your sweet tooth. ¡Que aproveche!

• After you walk through the market and leave through the exit farthest from Plaza Mayor, turn left, heading downhill on Calle del Conde de Miranda. At the first corner, turn right and cross the small plaza to the brick church in the far corner.

The proud coats of arms over the main entry announce the rich family that built this Hieronymite church and convent in 1607. In 17th-century Spain, the most prestigious thing a noble family could do was build and maintain a convent. To harvest all the goodwill created in your community, you’d want your family’s insignia right there for all to see. (You can see the donating couple, like a 17th-century Bill and Melinda Gates, kneeling before the communion wafer in the central panel over the entrance.) Inside is a cool and quiet oasis with a Last Supper altarpiece.

Now for a unique shopping experience. A half-block to the right from the church entrance is its associated convent—it’s the big brown door on the left, at Calle del Codo 3 (Mon-Sat 9:30-13:00 & 16:30-18:30, closed Sun). The sign reads: Venta de Dulces (Sweets for Sale). To buy goodies from the cloistered nuns, buzz the monjas button, then wait patiently for the sister to respond over the intercom. Say “dulces” (DOOL-thays), and she’ll let you in. When the lock buzzes, push open the door. It will be dark—look for a glowing light switch to turn on the lights. Walk straight in and to the left, then follow the sign to the torno—the lazy Susan that lets the sisters sell their baked goods without being seen. Scan the menu, announce your choice to the sequestered sister (she may tell you she has only one or two of the options available), place your money on the torno, and your goodies (and change) will appear. Galletas (shortbread cookies) are the least expensive item (a medio-kilo costs about €10). Or try the pastas de almendra (almond cookies).

• Continue uphill on Calle del Codo (where, in centuries past, those in need of bits of armor shopped—see the tiled street sign on the building) and turn left, heading toward the Plaza de la Villa. Before entering the square, notice an old door to the left of the Real Sociedad Económica sign, made of wood lined with metal. This is considered the oldest door in town on Madrid’s oldest building—inhabited since 1480. It’s set in a Moorish keyhole arch. Look up at what was a prison tower. Now continue into the square called Plaza de la Villa, dominated by Madrid’s...

The impressive structure features Madrid’s distinctive architectural style—symmetrical square towers, topped with steeples and a slate roof...Castilian Baroque. The building was Madrid’s Town Hall. Over the doorway, the three coats of arms sport many symbols of Madrid’s rulers: Habsburg crowns on each, castles of Castile (in center shield), and the city symbol—the berry-eating bear (shield on left). This square was the ruling center of medieval Madrid in the centuries before it became an important capital.

Imagine how Philip II took this city by surprise in 1561 when he decided to move the capital of Europe’s largest empire (even bigger than ancient Rome at the time) from Toledo to humble Madrid. To better administer their empire, the Habsburgs went on a building spree. But because their empire was drained of its riches by prolonged religious wars, they built Madrid with cheap brick instead of elegant granite. Baroque buildings in Spain didn’t need to be over-the-top propagandistic structures like elsewhere, as the people here didn’t need much encouragement to stay loyal to the Church.

The statue in the garden is of Philip II’s admiral, Don Alvaro de Bazán—mastermind of the Christian victory over the Turkish Ottomans at the naval battle of Lepanto in 1571. This pivotal battle, fought off the coast of Greece, slowed the Ottoman threat to Christian Europe. However, mere months after Bazán’s death in 1588, his “invincible” Spanish Armada was destroyed by England...and Spain’s empire began its slow fade.

• By the way, a cute little shop selling traditional monk- and nun-made pastries is just down the lane (El Jardin del Convento, at Calle del Cordón 1, on the back side of the cloistered convent you dropped by earlier). From here, walk along busy Calle Mayor, which leads downhill toward the Royal Palace. Along the way, at #80, you’ll pass a fine little shop specializing in books about Madrid. A few blocks down Calle Mayor, on a tiny square, you’ll find the...

This statue memorializes a 1906 assassination attempt. The target was Spain’s King Alfonso XIII and his bride, Victoria Eugenie, as they paraded by on their wedding day. While the crowd was throwing flowers, an anarchist (as terrorists used to be called) threw a bouquet lashed to a bomb from a balcony at #84 (across the street). He missed the royal newlyweds, but killed 28 people. Gory photos of the event hang inside the Casa Ciriaco restaurant, which now occupies #84 (photos to the right of the entrance, or in an outside window). The king and queen went on to live to a ripe old age, producing many great-grandchildren, including the current king, Felipe VI.

• Continue down Calle Mayor one more block to a busy street, Calle de Bailén. Take in the big, domed...

Madrid’s massive, gray-and-white cathedral (110 yards long and 80 yards high) opened in 1993, 100 years after workers started building it. This is the side entrance for tourists. Climbing the steps to the church courtyard, you’ll come to a monument to Pope John Paul II’s 1993 visit, when he consecrated Almudena—ending Madrid’s 300-year stretch of requests for a cathedral of its own.

If you go inside (€1 donation requested), stop in the center, immediately under the dome, and face the altar. Beyond it, colorful paintings—rushed to completion for the pope’s ’93 visit—brighten the apse. In the right transept the faithful venerate a 15th-century Gothic altarpiece with a favorite statue of the Virgin Mary—a striking treasure considering the otherwise 20th-century Neo-Gothic interior. Gape up at the glittering 5,000-pipe organ in the rear of the nave.

The church’s historic highlight is the 13th-century coffin (empty, painted leather on wood, in a chapel behind the altar) of Madrid’s patron saint, Isidro. A humble farmer, the exceptionally devout Isidro was said to have been helped by angels who did the plowing for him while he prayed. Forty years after he died, this coffin was opened, and his body was found to have been miraculously preserved. This convinced the pope to canonize Isidro as the patron saint of Madrid and of farmers, with May 15 as his feast day.

• Leave the church from the transept where you entered and turn left. Hike around the church to its rarely used front door. Climb the cathedral’s front steps and face the imposing...

Since the ninth century, this spot has been Madrid’s center of power: from Moorish castle to Christian fortress to Renaissance palace to the current structure, built in the 18th century. With its expansive courtyard surrounded by imposing Baroque architecture, it represents the wealth of Spain before its decline. Its 2,800 rooms, totaling nearly 1.5 million square feet, make it Europe’s largest palace. Stretching toward the mountains on the left is the vast Casa del Campo (a former royal hunting ground and now city park).

• You could visit the palace now, using my self-guided tour.

Or, to follow the rest of this walk back to Puerta del Sol, continue one long block north up Calle de Bailén (walking alongside the palace) toward the Madrid Tower skyscraper. This was a big deal in the 1950s when it was one of the tallest buildings in Europe (460 feet tall) and the pride of Franco and his fascist regime. The tower marks Plaza de España, and the end of my “Gran Vía Walk.” To Spaniards, this symbolizes the boom time the country enjoyed when it sided with the West during the Cold War (allowing the US and not the USSR to build military bases in Spain). Walk to where the street opens up and turn right, facing the statue, park, and royal theater.

As its name suggests, this square faces east. The grand yet people-friendly plaza is typical of today’s Europe, where energetic governments are converting car-congested wastelands into inviting public spaces like this. Where’s the traffic? Under your feet. A past mayor of Madrid earned the nickname “The Mole” for all the digging he did.

Notice the quiet. You’re surrounded by more than three million people, yet you can hear the birds, bells, and fountain. The park is decorated with statues of Visigothic kings who ruled from the fifth to eighth century. Romans allowed them to administer their province of Hispania on the condition that they’d provide food and weapons to the empire. The Visigoths inherited real power after Rome fell, but lost it to invading Moors in 711. The fine bronze equestrian statue of Philip IV was a striking technical feat in its day, as the horse stood up on its hind legs (possible only with the help of Galileo’s clever calculations and by using the tail for more support). The king faces Madrid’s opera house, the 1,700-seat Royal Theater (Teatro Real), rebuilt in 1997.

• Walk along the Royal Theater, on the right side, to the...

This square is marked by a statue of Isabel II, who ruled Spain in the 19th century and was a great patron of the arts. Although she’s immortalized here, Isabel had a rocky reign, marked by uprisings and political intrigue. A revolution in 1868 forced her to abdicate, and she lived out her life in exile.

Facing the opera house is a grand old cinema (now closed). During the dictatorial days of Franco, movies were always dubbed in Spanish, making them easier to censor. (In one famously awkward example, Franco’s censors were scandalized by a film that implied a man and a woman were having an affair, so they edited the voice track to make the characters into brother and sister. But the onscreen chemistry was still sexually charged—and the censors inadvertently turned an illicit relationship into an incestuous one.) Movies in Spain are still mostly dubbed (to see a movie here without dubbing, look for “V.O.”, which means “original version”).

• From here, follow Calle del Arenal, walking gradually uphill. You’re heading straight to Puerta del Sol.

As depicted on the tiled street signs, this was the “street of sand”—where sand was stockpiled during construction. Each cross street is named for a medieval craft that, historically, was plied along that lane (for example, “Calle de Bordadores” means “Street of the Embroiderers”). Wander slowly uphill. As you stroll, imagine this street as a traffic inferno—which it was until the city pedestrianized it a decade ago (and now monitor it with police cameras atop posts at intersections). Notice also how orderly the side streets are. Where a mess of cars once lodged chaotically on the sidewalks, orderly bollards (bolardos) now keep vehicles off the walkways. The fancier facades (such as the former International Hotel at #19) are in the “eclectic” style (Spanish for Historicism—meaning a new interest in old styles) of the late 19th century.

Continue 200 yards up Calle del Arenal to a brick church on the right. As you walk, consider how many people are simply out strolling. The paseo is a strong tradition in this culture—people of all generations enjoy being out, together, strolling. And local governments continue to provide more and more pedestrianized boulevards to make the paseo better than ever.

The brick St. Ginés Church (on the right) means temptation to most locals. It marks the turn to the best chocolatería in town. From the uphill corner of the church, look to the end of the lane where—like a high-calorie red-light zone—a neon sign spells out Chocolatería San Ginés...every local’s favorite place for hot chocolate and churros (always open). Also notice the charming bookshop clinging like a barnacle to the wall of the church. It’s been selling books on this spot since 1650.

Next door is the Joy Eslava disco, a former theater famous for operettas in the Gilbert and Sullivan days and now a popular club. In Spain, you can do it all when you’re 18 (buy tobacco, drink, drive, serve in the military). This place is an alcohol-free disco for the younger kids until midnight, when it becomes a thriving adult space, with the theater floor and balconies all teeming with clubbers. Their slogan: “Go big or go home.”

The Starbucks on the opposite corner (at #14) is popular with young locals for its inviting ambience and American-style muffins (and free Wi-Fi), even though the coffee is too tame for many Spaniards.

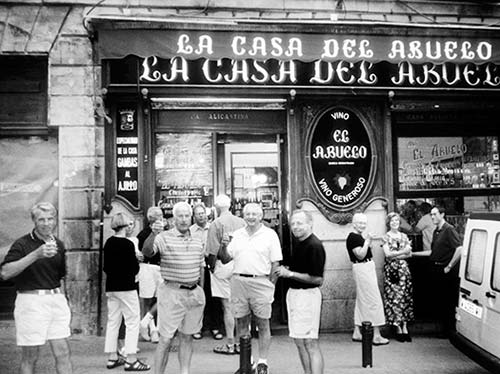

Kitty corner (at #7) is Ferpal, an old-school deli with an inviting bar and easy takeout options. Wallpapered with ham hocks, it’s famous for selling the finest Spanish cheeses, hams, and other tasty treats. Spanish saffron is half what you’d pay for it back in the US. While they sell quality sandwiches, cheap and ready-made, it’s fun to buy some bread and—after a little tasting—choose a ham or cheese for a memorable picnic or snack. If you’re lucky, you may get to taste a tiny bit of Spain’s best ham (Ibérico de Bellota). Close your eyes and let the taste fly you to a land of very happy acorn-fed pigs.

Across the street, in a little mall (at #8), a lovable mouse cherished by Spanish children is celebrated with a six-inch-tall bronze statue in the lobby. Upstairs is the fanciful Casita Museo de Ratón Pérez (€3, daily, Spanish only) with a fun window display. A steady stream of adoring children and their parents pour through here to learn about the wondrous mouse that is Spain’s tooth fairy.

Just uphill (at #6) is an official retailer of Real Madrid football (soccer) paraphernalia. Many Europeans come to Madrid primarily to see its 80,000-seat Bernabéu Stadium. Madrid has crosstown rival teams (similar to Chicago’s Cubs and White Sox, or New York’s Yankees and Mets). Atlético de Madrid is the working-class underdog (like the Mets), while Real Madrid (the Yankees of Spanish football) has piles of money and wins piles of championships. Step inside to see posters of the happy team posing with the latest trophy.

Across the street at #3 is Pronovias, a famous Spanish wedding-dress shop that attracts brides-to-be from across Europe. These days, the current generation of Spaniards often just shack up without getting married. Those who do get married are more practical—preferring a down payment on a condo to a fancy wedding with a costly dress.

• You’re just a few steps from where you started this walk, at Puerta del Sol. Back in the square, you’re met by a statue popularly known as La Mariblanca. This mythological Spanish Venus—with Madrid’s coat of arms at her feet—stands tall amid all the modernity, as if protecting the people of this great city.

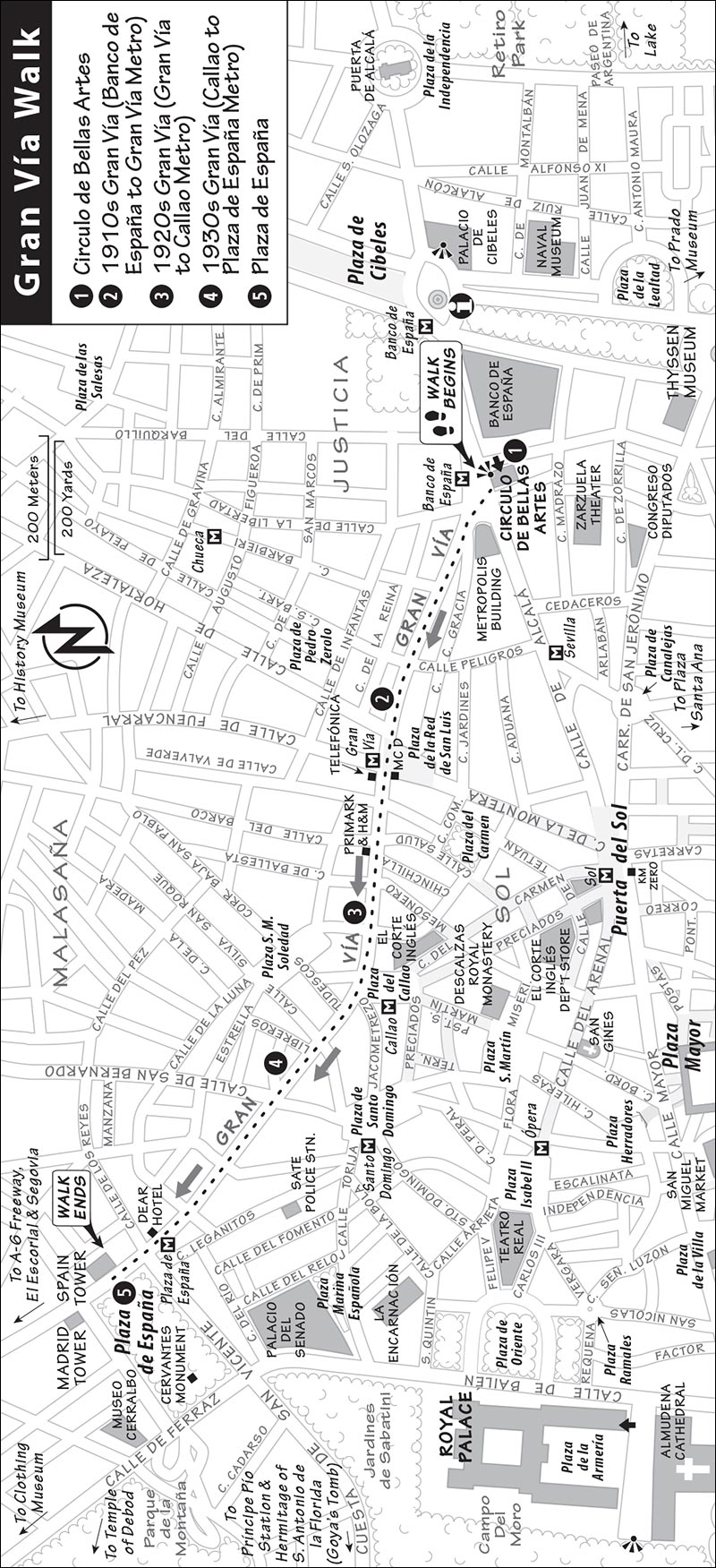

For a walk down Spain’s version of Fifth Avenue, stroll the Gran Vía. Built primarily between 1910 and the 1930s, this boulevard, worth ▲, affords a fun view of early 20th-century architecture and a chance to be on the street with workaday Madrileños. I’ve broken this self-guided walk into five sections, each of which was the ultimate in its day.

• Start at the skyscraper at Calle de Alcalá #42 (Metro: Banco de España).

This 1920s skyscraper has a venerable café on its ground floor (free entry to enjoy its belle époque-style interior) and the best rooftop view around. Ride the elevator to the seventh-floor roof terrace/lounge and bar (€4, Mon-Fri 9:30-21:00, Sat-Sun from 11:00). Stand under a black Art Deco statue of Minerva, perhaps put here to associate Madrid with this mythological protectress of culture and high thinking, and survey the city. Start in the far left and work your way around the perimeter for a clockwise tour.

Looking down to the left, you’ll see the gold-fringed dome of the landmark Metropolis building (inspired by Hotel Negresco in Nice), once the headquarters of an insurance company. It stands at the start of the Gran Vía and its cancan of proud facades celebrating the good times in pre-civil war Spain. On the horizon, the Guadarrama Mountains hide Segovia. Farther to the right, in the distance, skyscrapers mark the city’s north gate, Puerta de Europa (with its striking slanted twin towers peeking from behind other towers). Round the terrace corner. The big traffic circle and fountain below are part of Plaza de Cibeles, with its ornate and bombastic cultural center and observation deck (Palacio de Cibeles—built in 1910 as the post-office headquarters, and since 2006 the Madrid City Hall). Behind that is the vast Retiro Park. Farther to the right (at the next corner of the terrace), the big low-slung building surrounded by green is the Prado Museum.

• Descend the elevator and cross the busy boulevard immediately in front of Círculo de Bellas Artes to reach the start of Gran Vía.

This first stretch, from the Banco de España Metro stop to the Gran Vía Metro stop, was built in the 1910s as a strip of luxury stores. The Bar Chicote (at #12) is a classic cocktail bar that welcomed Hemingway and the stars of the day. While the people-watching and window-shopping can be enthralling, be sure to look up and enjoy the beautiful facades, too.

The second stretch, from the Gran Vía Metro stop to the Callao Metro stop, starts where two recently pedestrianized streets meet up. To the right, Calle de Fuencarral is the trendiest pedestrian zone in town, with famous brand-name shops and a young vibe. To the left, Calle de la Montera is notorious for its prostitutes. The action pulses from the McDonald’s down a block or so. Some find it an eye-opening little detour.

The 14-story Telefónica skyscraper is nearly 300 feet tall. Perched here at the highest point around, it seems even taller. It was one of the city’s first skyscrapers (the tallest in Spain until the 1950s) with a big New York City feel—and with a tiny Baroque balcony, as if to remind us we’re still in Spain. Telefónica was Spain’s only telephone company through the Franco age (and was notorious for overbilling people, with nothing itemized and no accountability). Today it’s one of Spain’s few giant blue-chip corporations.

With plenty of money and a need for corporate goodwill, the building houses the free Espacio Fundación Telefónica (Tue-Sun 10:00-20:00, closed Mon), with an art gallery, kid-friendly special exhibits, and a fun permanent exhibit telling the story of telecommunications, from telegraphs to iPhones. This exhibit fills the second floor amid exposed steel beams—a space where a thousand “09 girls,” as operators were called back then, once worked.

Farther along is a strip of department stores, including Primark, the first modern department store in town. Just before the Callao Metro station, at #37, step into the H&M department store for a dose of a grand old theater lobby.

The final stretch, from the Callao Metro stop to Plaza de España, is considered the “American Gran Vía,” built in the 1930s to emulate the buildings of Chicago and New York City. The Schweppes building (Art Deco in the Chicago style, with its round facade and curved windows) was radical and innovative in 1933. This section of Gran Vía is the Spanish version of Broadway, with all the big theaters and plays. These theaters survive thanks to Spanish translations of Broadway shows, productions which get a huge second life here and in Latin America.

Across from the Teatro Lope de Vega (at #60) is a quasi fascist-style building (#57). It’s a bank from 1930 capped with a stern statue that looks like an ad for using a good, solid piggy bank. Looking up the street toward the Madrid Tower, the buildings become even more severe.

The Dear Hotel (at #80) has a restaurant on its 14th floor and a rooftop lounge and small bar above that. (Walk confidently through the hotel lobby, ride the elevator to the top, pass through the restaurant, and climb the stairs from the terrace outside to the rooftop.) The views from here are among the best in town.

The end of Gran Vía is marked by Plaza de España (with a Metro station of the same name). While statues of the epic Spanish characters Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (part of a Cervantes monument) are ignored in the park, two Franco-era buildings do their best to scrape the sky above. Franco wanted to show he could keep up with America, so he had the Spain Tower (shorter) and Madrid Tower (taller) built in the 1950s. But they reminded people more of Moscow than the USA. The future of the Plaza de España looks brighter than its past. Major renovation plans are in the works to limit traffic, invite more pedestrians, and link it up with some of the city’s bike paths.

Spain’s Royal Palace (Palacio Real) is Europe’s third-greatest palace, after Versailles and Vienna’s Schönbrunn. It has arguably the most sumptuous original interior, packed with tourists and royal antiques.

The palace is the product of many kings over several centuries. Philip II (1527-1598) made a wooden fortress on this site his governing center when he established Madrid as Spain’s capital. When that palace burned down, the current structure was built by King Philip V (1683-1746). Philip V wanted to make it his own private Versailles, to match his French upbringing: He was born in Versailles—the grandson of Louis XIV—and ordered his tapas in French. His son, Charles III (whose statue graces Puerta del Sol), added interior decor in the Italian style, since he’d spent his formative years in Italy. These civilized Bourbon kings were trying to raise Spain to the cultural level of the rest of Europe. They hired foreign artists to oversee construction and established local Spanish porcelain and tapestry factories to copy works done in Paris or Brussels. Over the years, the palace was expanded and enriched, as each Spanish king tried to outdo his predecessor.

Today’s palace is ridiculously supersized—with 2,800 rooms, tons of luxurious tapestries, a king’s ransom of chandeliers, frescoes by Tiepolo, priceless porcelain, and bronze decor covered in gold leaf. While these days the royal family lives in a mansion a few miles away, this place still functions as the ceremonial palace, used for formal state receptions, royal weddings, and tourists’ daydreams.

Cost and Hours: €10, €11 if there are special exhibits; open daily 10:00-20:00, Oct-March 10:00-18:00, last entry one hour before closing; from Puerta del Sol, walk 15 minutes down pedestrianized Calle del Arenal (Metro: Ópera); palace can close for royal functions—confirm in advance.

Information: Tel. 914-548-800, www.patrimonionacional.es.

Crowd-Beating Tips: The palace is free for locals—and most crowded—Monday-Thursday 18:00-20:00 in summer and 16:00-18:00 in winter. On any day, arrive early or go late to avoid lines and crowds.

Visitor Information: Short English descriptions posted in each room complement what I describe in my tour. The museum guidebook demonstrates a passion for meaningless data.

Tours: The excellent €4 audioguide is much more interesting than the museum guidebook. Or download in advance the helpful app, “Royal Palace of Madrid,” that takes you through the palace in three segments ($2 fee). You can also join a €4 guided tour. Check the time of the next English-language tour and decide as you buy your ticket; the tours are dry, depart sporadically, and aren’t worth a long wait.

Services: Free lockers and a WC are just past the ticket booth. Upstairs you’ll find a more serious bookstore with good books on Spanish history.

Eating: Though the palace has a refreshing air-conditioned cafeteria upstairs (with salad bar), I prefer to walk a few minutes and find a place near the Royal Theater or on Calle del Arenal. Another great option is $$ Café de Oriente, boasting good lunch specials and fin-de-siècle elegance immediately across the park from the Royal Palace.

Self-Guided Tour

Self-Guided TourYou’ll follow a simple one-way circuit on a single floor covering more than 20 rooms.

• Buy your ticket, pass through the bookstore, stand in the middle of the vast open-air courtyard, and face the palace entrance.

1 Palace Exterior: The palace sports the French-Italian Baroque architecture so popular in the 18th century—heavy columns, classical-looking statues, a balustrade roofline, and false-front entrance. The entire building is made of gray-and-white local stone (very little wood) to prevent the kind of fire that leveled the previous castle. Imagine the place in its heyday, with a courtyard full of soldiers on parade, or a lantern-lit scene of horse carriages arriving for a ball.

• Enter the palace and show your ticket.

Palace Lobby: In the old days, horse-drawn carriages would drop you off here. Today, stretch limos do the same thing for gala events. (If you’re taking a guided palace tour, this is where you wait to begin.) The modern black bust in the corner is of Juan Carlos I, a “people’s king,” who is credited with bringing democracy to Spain after 36 years under dictator Franco. (Juan Carlos passed the throne to his son in 2014.)

2 Grand Stairs: Gazing up the imposing staircase, you can see that Spain’s kings wanted to make a big first impression. Whenever high-end dignitaries arrive, fancy carpets are rolled down the stairs (notice the little metal bar-holding hooks). Begin your ascent, up steps that are intentionally shallow, making your climb slow and regal. Overhead, the white-and-blue ceiling fresco gradually opens up to your view. It shows the Spanish king, sitting on clouds, surrounded by female Virtues.

At the first landing, the burgundy coat of arms represents Felipe VI, the son of Spain’s previous king, Juan Carlos. J. C. knew Spain was ripe for democracy after Francisco Franco’s dictatorial regime. Rather than become “Juan the Brief” (as some were nicknaming him), he returned real power to the parliament. You’ll see his (figure) head on the back of some Spanish €1 and €2 coins.

Continue up to the top of the stairs. Before entering the first room, look to the right of the door to find a white marble bust of J. C.’s great-great-g-g-g-great-grandfather Philip V, who began the Bourbon dynasty in Spain in 1700 and had this palace built.

3 Royal Guard/Halberdiers Room: The palace guards used to hang out in this relatively simple room. Notice the two fake doors, added to give the room symmetry. The old clocks—still in working order—are part of a collection of hundreds amassed as a hobby by Spain’s royal family. Throughout the palace, the themes chosen for the ceiling frescoes relate to the function of the room they decorate. In this room, the ceiling fresco is the first we’ll see in a series by the great Venetian painter Giambattista Tiepolo. It depicts the legendary hero Aeneas (in red, with the narrow face of Charles III) standing in the clouds of heaven, gazing up at his mother Venus (with the face of Charles’ own mother).

Notice the carpets in this room. Although much of what you see in the palace dates from the 18th century, the carpet on the left (folded over to show the stitching) is new, from 1991. It was produced by Madrid’s royal tapestry factory, the same works that made the older original carpet (displayed next to the modern one). Though recently produced, the new carpet was woven the traditional way—by hand.

4 Hall of Columns: Originally a ballroom and dining room, today this space is used for formal ceremonies and intimate concerts. This is where Spain formally joined the European Union in 1985 (the fancy table used for the event is in the Crown Room) and honored its national soccer team after their 2010 World Cup victory. The tapestries (like most you’ll see in the palace) are 17th-century Belgian, from designs by Raphael.

The central theme in the ceiling fresco (by Jaquinto, following Tiepolo’s style) is Apollo driving the chariot of the sun, while Bacchus enjoys wine, women, and song with a convivial gang. This is a reminder that the mark of a good king is to drive the chariot of state as smartly as Apollo, while providing an environment where the people can enjoy life to the fullest.

• The next several rooms were the living quarters of King Charles III (r. 1759-1788). First comes his 5 drawing room (with red-and-gold walls), where the king would enjoy the company of a similarly great ruler—the Roman emperor Trajan—depicted “triumphing” on the ceiling. The heroics of Trajan, one of two Roman emperors born in Spain, naturally made the king feel good. Next, you enter the blue-walled...

6 Antechamber: This was Charles III’s dining room. The four paintings—all original by Francisco de Goya—are of Charles III’s son and successor, King Charles IV (looking a bit like a dim-witted George Washington), and his wife, María Luisa (who wore the pants in the palace). María Luisa was famously hands-on, tough, and businesslike, while Charles IV was pretty wimpy as far as kings go. To meet the demand for his work, Goya made other copies of these portraits, which you’ll see in the Prado.

The 12-foot-tall clock—showing Cronus, God of time, in porcelain, bronze, and mahogany—sits on a music box. Reminding us of how time flies, Cronus is shown both as a child and as an old man. The palace’s clocks are wound—and reset—once a week (they grow progressively less accurate as the week goes on). The gilded decor you see throughout the palace is bronze with gold leaf. Velázquez’s famous painting, Las Meninas (which you’ll marvel at in the Prado), originally hung in this room.

7 Gasparini Room: (Gasp!) The entire room is designed, top to bottom, as a single gold-green-rose ensemble: from the frescoed ceiling to the painted stucco figures, silk-embroidered walls, chandelier, furniture, and multicolored marble floor. Each marble was quarried in, and therefore represents, a different region of Spain. Birds overhead spread their wings, vines sprout, and fruit bulges from the surface. With curlicues everywhere (including their reflection in the mirrors), the room dazzles the eye and mind. It’s a triumph of the Rococo style, with exotic motifs such as the Chinese people sculpted into the corners of the ceiling. (These figures, like many in the palace, were formed from stucco, or wet plaster.) The fabric gracing the walls was recently restored. Sixty people spent three years replacing the rotten silk fabric and then embroidering back on the silver, silk, and gold threads.

Note the micro-mosaic table—a typical royal or aristocratic souvenir from any visit to Rome in the mid-1800s. The chandelier, the biggest in the palace, is mesmerizing, especially with its glittering canopy of crystal reflecting in the wall mirrors.

This was the king’s dressing room. For a divine monarch, dressing was a public affair. The court bigwigs would assemble here as the king, standing on a platform—notice the height of the mirrors—would pull on his leotards and toy with his wig.

• In the next room, the silk wallpaper is from modern times—the intertwined “J. C. S.” indicates the former monarchs Juan Carlos I and Sofía. Pass through the silk room to reach...

8 Charles III Salon: Charles III died here in his bed in 1788. His grandson, Ferdinand VII, redid the room to honor the great man. The room’s blue color scheme recalls the blue-clad monks of Charles’ religious order. A portrait of Charles (in blue) hangs on the wall. The ceiling fresco shows Charles establishing his order, with its various (female) Virtues. At the base of the ceiling (near the harp player) find the baby in his mother’s arms—that would be Ferdy himself, the long-sought male heir, preparing to continue Charles’ dynasty.

The chandelier is in the shape of the fleur-de-lis (the symbol of the Bourbon family) capped with a Spanish crown. As you exit the room, notice the thick walls between rooms. These hid service corridors for servants, who scurried about mostly unseen.

9 Porcelain Room: This tiny but lavish room is paneled with green-white-gold porcelain garlands, vines, babies, and mythological figures. The entire ensemble was disassembled for safety during the civil war. (Find the little screws in the greenery that hides the seams between panels.) Notice the clock in the center with Atlas supporting the world on his shoulders.

10 Yellow Lounge: This was a study for Charles III. The properly cut crystal of the chandelier shows all the colors of the rainbow. Stand under it, look up, and sway slowly to see the colors glitter. This is not a particularly precious room. But its decor pops because the lights are generally left on. Imagine the entire palace as brilliant as this when fully lit. As you leave the room, look back at the chandelier to notice its design of a temple with a fountain inside.

• Next comes the...

11 Gala Dining Room: Up to 12 times a year, the king entertains as many as 144 guests at this bowling lane-size table, which can be extended to the length of the room. The parquet floor was the preferred dancing surface when balls were held in this fabulous room. Note the vases from China, the tapestries, and the ceiling fresco depicting Christopher Columbus kneeling before Ferdinand and Isabel, presenting exotic souvenirs and his new, red-skinned friends. Imagine this hall in action when a foreign dignitary dines here. The king and queen preside from the center of the room. Find their chairs (slightly higher than the rest). The tables are set with fine crystal and cutlery (which we’ll see a couple of rooms later). And the whole place glitters as the 15 chandeliers (and their 900 bulbs) are fired up. (The royal kitchens, where the gala dinners were prepared, may be open for viewing; ask the staff where to enter.)

• Pass through the next room, known as the 12 Cinema Room because the royal family once enjoyed Sunday afternoons at the movies here. The royal string ensemble played here to entertain during formal dinners. From here, if the next two rooms are open, move into the...

13 Silver Room: Some of this 19th-century silver tableware—knives and forks, bowls, salt and pepper shakers, and the big punch bowl—is used in the Gala Dining Room on special occasions. If you look carefully, you can see quirky royal necessities, including a baby’s silver rattle and fancy candle snuffers.

• Head straight ahead to the...

14 Crockery and Crystal Rooms: Philip V’s collection of china is the oldest and rarest of the various pieces on display; it came from China before that country was opened to the West. Since Chinese crockery was in such demand, any self-respecting European royal family had to have its own porcelain works (such as France’s Sèvres or Germany’s Meissen) to produce high-quality knockoffs (and cutesy Hummel-like figurines). The porcelain technique itself was kept a royal secret. As you leave, check out Isabel II’s excellent 19th-century crystal ware.

• Exit to the hallway and notice the interior courtyard you’ve been circling one room at a time.

15 Courtyard: You can see how the royal family lived in the spacious middle floor while staff was upstairs. The kitchens, garage, and storerooms were on the ground level. The new king, Felipe VI, married a commoner (for love) and celebrated their wedding party in this courtyard, which was decorated as if another palace room. Spain’s royals take their roles and responsibilities seriously—making a point to be approachable and empathizing with their subjects—and are very popular.

• Between statues of two of the giants of Spanish royal history (Isabel and Ferdinand), you’ll enter the...

16 Royal Chapel: This chapel is used for private concerts and funerals. The royal coffin sits here before making the sad trip to El Escorial to join the rest of Spain’s past royalty (see next chapter). The glass case contains the entire body of St. Felix, given to the Spanish king by the pope in the 19th century. Note the “crying room” in the back for royal babies. While the royals rarely worship here (they prefer the cathedral adjacent to the palace), the thrones are here just in case.

• Pass through the 17 Queen’s Boudoir—where royal ladies hung out—and into the...

18 Stradivarius Room: Of all the instruments made by Antonius Stradivarius (1644-1737), only 300 survive. This is the world’s best collection and the only matching quartet set: two violins, a viola, and a cello. Charles III, a cultured man, fiddled around with these. Today, a single Stradivarius instrument might sell for $15 million.

• Continue into the room at the far left.

19 Crown Room: The stunning crown of Bourbon Charles III, and the scepter of the last Hapsburg king, Charles II, are displayed in a glass case in the middle. Look for the 2014 proclamations of Juan Carlos’ abdication of the crown and Felipe VI’s acceptance as king of Spain. Notice which writing implement each man chose to sign with: Juan Carlos’ traditional classic pen and Felipe VI’s modern one. The fine inlaid marble table in this room is important to Spaniards because it was used when King Juan Carlos signed the treaty finalizing Spain’s entry into the European Union in 1985.

• Walk back through the Stradivarius Room and into the courtyard hallway. Continue your visit through the Antechamber, where ambassadors would wait to present themselves, and the Small Official Chambers, where officials are received by royalty and have their photos taken. Walk through two rooms—the blue official antechamber with royal portraits and busts of Juan Carlos, Sofía, and Felipe VI, and the red official waiting room with tapestries, paintings, and a Tiepolo ceiling fresco—to reach the grand finale, the...

20 Throne Room: This room, where the Spanish monarchs preside, is one of the palace’s most glorious. And it holds many of the oldest and most precious things in the palace: silver-and-crystal chandeliers (from Venice’s Murano Island), elaborate lions, and black bronze statues from the fortress that stood here before the 1734 fire. The 12 mirrors, impressively large in their day, each represent a different month.

The throne stands under a gilded canopy, on a raised platform, guarded by four lions (symbols of power found throughout the palace). The coat of arms above the throne shows the complexity of the Spanish empire across Europe—which, in the early 18th century, included Naples, Sicily, parts of the Netherlands, and more. Though the room was decorated under Charles III (late 18th century), the throne itself dates only from 1977. In Spain, a new throne is built for each king or queen, complete with a gilded portrait on the back. The room’s chairs also indicate the previous monarchs—“JC I” and “Sofía.” With Juan Carlos’ abdication, the chairs may not have changed names yet.

Today, this room is where the king’s guests salute him before they move on to dinner. He receives them relatively informally...standing at floor level, rather than seated up on the throne.

The ceiling fresco (1764) is the last great work by Tiepolo, who died in Madrid in 1770. His vast painting (88 × 32 feet) celebrates the vast Spanish empire—upon which the sun also never set. The Greek gods look down from the clouds, overseeing Spain’s empire, whose territories are represented by the people ringing the edges of the ceiling. Find the Native American (hint: follow the rainbow to the macho red-caped conquistador who motions to someone he has conquered). From the near end of the room (where tourists stand), look up to admire Tiepolo’s skill at making a pillar seem to shoot straight up into the sky. The pillar’s pedestal has an inscription celebrating Tiepolo’s boss, Charles III (“Carole Magna”). Notice how the painting spills over the gilded wood frame, where 3-D statues recline alongside 2-D painted figures. All of the throne room’s decorations—the fresco, gold garlands, mythological statues, wall medallions—unite in a multimedia extravaganza.

• Exit the palace down the same grand stairway you climbed at the start. Cross the big courtyard, heading to the far-right corner to the...

21 Armory: Here you’ll find weapons and armor belonging to many great Spanish historical figures. While some of it was actually for fighting, remember that the great royal pastimes included hunting and tournaments, and armor was largely for sport or ceremony. Much of this armor dates from Habsburg times, before this palace was built (it came here from the earlier fortress or from El Escorial). Circle the big room clockwise.

In the three glass cases on the left, you’ll see the oldest pieces in the collection, from the 15th century. In the central case (case III), the shield, sword, belt, and dagger belonged to Boabdil, the last Moorish king, who surrendered Granada in 1492. In case IV, the armor and swords belonged to Ferdinand, the husband of Isabel, and Boabdil’s contemporary.

The center of the room is filled with knights in armor on horseback—mostly suited up for tournament play. Many of the pieces belonged to the two great kings who ruled Spain at its 16th-century peak, Charles I and his son Philip II.

The long wall on the left displays the personal armor wardrobe of Charles I (a.k.a. the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V). At the far end, you’ll meet Charles on horseback. The mannequin of the king wears the same armor and assumes the same pose as in Titian’s famous painting of him (in the Prado).

The opposite wall showcases the armor and weapons of Philip II, the king who watched Spain start its long slide downward. Philip, who impoverished Spain with his wars against the Protestants, anticipated that debt collectors would ransack his estate after his death and specifically protected his impressive collection of armor by founding this armory.