2Evidentiality of the Tibetan verb snang

2.1Introduction

This study analyzes the evidential usage of the Tibetan verb snang in spoken and written Tibetan. As is well known to Tibetologists, the Tibetan verb ’dug (which originally meant ‘to sit, remain, or stay’) has a tendency to become an evidential marker. Thus far, a number of studies have shown the evidentiality of the verb ’dug in many Tibetan dialects (Yukawa 1966; DeLancey 1986; Agha 1993; Hongladarom 1994; Tournadre 1996; Hoshi 1997; Häsler 1999; Garrett 2001; Hill 2012, etc.). In the Lhasa dialect of Central Tibetan ’dug is described as a sensory evidential (Hill 2012: 329). In the same way as ’dug, the verb snang also shows evidential senses in some dialects that are geographically widely distributed. snang originally meant ‘to emit light, to be seen, appear’ and was grammaticalized into an evidential marker. In contrast to ’dug, snang has so far enjoyed little research attention, with the exception of a few publications (Suzuki 2006, 2012; Suzuki and Tshe ring 2009). Specifically, the geographical distribution and semantic variations of snang have not yet been investigated. This contribution presents a first attempt to consider the evidential use of Tibetan snang in a range of cases and to analyze its semantic variation, thus providing new data on the study of evidentials in Tibetan.

We will first provide an overview of the evidential usage of snang and consult the trace of evidential snang in Written Tibetan. Based on these data, the following points will be demonstrated: 1) the distribution of evidential snang, and 2) the semantic map of evidential snang.

2.2The Tibetan verb snang

First, we will examine the basic meaning of snang. According to Jäschke (1949 [1881]), the verb snang generally means: (i) to emit light, to shine, to be bright; shin tu mi snang ba’i mun pa ‘darkness entirely devoid of light’, (ii) to be seen or perceived, to show one’s self, to appear; da lta rgyu zhig snang ngo ‘now an opportunity shows itself’, (iii) =yod pa; zer ba snang ‘it is said’. Since yod pa is one of the existential verbs in Tibetan, (iii) suggests that snang can be used as an existential verb. Although evidential meanings are not mentioned in dictionaries, descriptive studies show that snang is used as an evidential (sometimes an evidential-like) marker in some spoken Tibetan.

A typological study by Aikhenvald (2004: 271) notes that evidential specifications come from: (i) verbs of speech, (ii) verbs of perception, and, more rarely, from (iii) verbs of other semantic groups. Tibetan snang belongs to the second type.

2.3Evidential snang in spoken Tibetan

We examine some examples of evidential meanings of snang in the following Tibetan dialects.

Western Archaic Tibetan

Balti (Tyakshi)

Balti (Turtuk)

Balti (Khaplu)

Amdo Tibetan

dPa’ ris

Thewo

Kham Tibetan

Dongwang

rGyalthang

Bathang

Budy

Zhollam

Shar Tibetan

sKyangtshang

Central Tibetan

Reting

Nyimachangra

Drigung

Penpo

Aikenvald (2004: 65) classifies evidential meanings into six types: (i) visual, (ii) sensory, (iii) inferential, (iv) assumptive, (v) hearsay, and (vi) quotative. Evidential snang in spoken Tibetan is related to (i) visual, (ii) sensory, and (iii) inferential. In what follows, we will see examples from each dialect.

2.3.1Western Archaic Tibetan

Western Archaic Tibetan (Róna-Tas 1966, Bielmeier 1985) is spoken in north India and Pakistan and includes Ladakhi, Purik, and Balti. In Balti, snang is used as an evidential marker. The data from three dialects of Balti are shown here. Read classifies naŋ as a verb and said it “implies to be, in the sense of ‘apparently is’ or ‘looks’ to be” (1934: 61). Bielmeier (1985: 101) classifies -aŋ (suffix form of naŋ) as an auxiliary verb, and in the glossary, he repeats the explanation of Read (1934).

On the other hand, evidential snang is not attested in Ladakhi (Koshal 1979; Norman 2001) and Purik (Rangan 1979). In Ladakhi, duk (visual evidential) and rak (non-visual evidential) are used as evidential markers.

2.3.1.1Tyakshi dialect of Balti

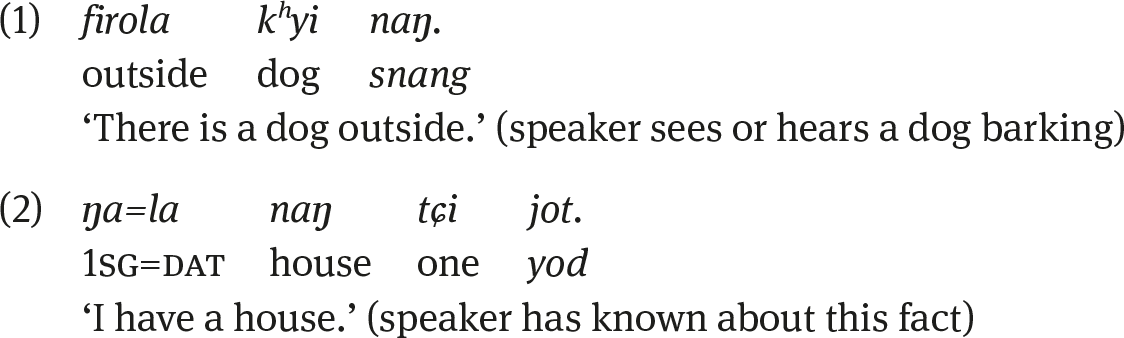

Tyakshi is one of the Balti dialects spoken in North India. The Tyakshi data are taken from the present author’s field notes. In this dialect, naŋ (as well as its negative form medaŋ) is used as an evidential marker. This verb can be used as (a) an existential verb (expressing existence and possession), and (b) an auxiliary in both adjective and verb clauses, and marks ‘speaker’s sensory evidential’ (both visual and non-visual).

The verb naŋ contrasts with another existential verb jot, which marks ‘speaker’s knowledge.’

Tab. 1: Existential Verbs in Tyaksi Dialect.

| Affirmative | Negative | |

| Sensory evidential | naŋ | medaŋ |

| Speaker’s knowledge | jot | met |

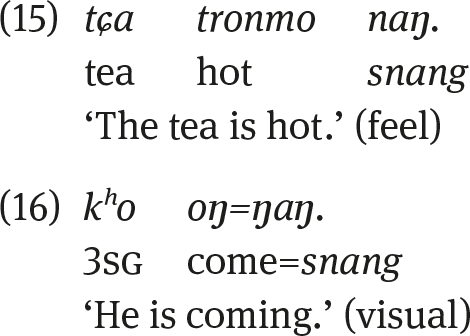

The first two examples show naŋ and jot used as existential verbs. Example (1) illustrates that naŋ can indicate both visual and non-visual evidence. On the other hand, jot can show speaker’s knowledge, as in (2).

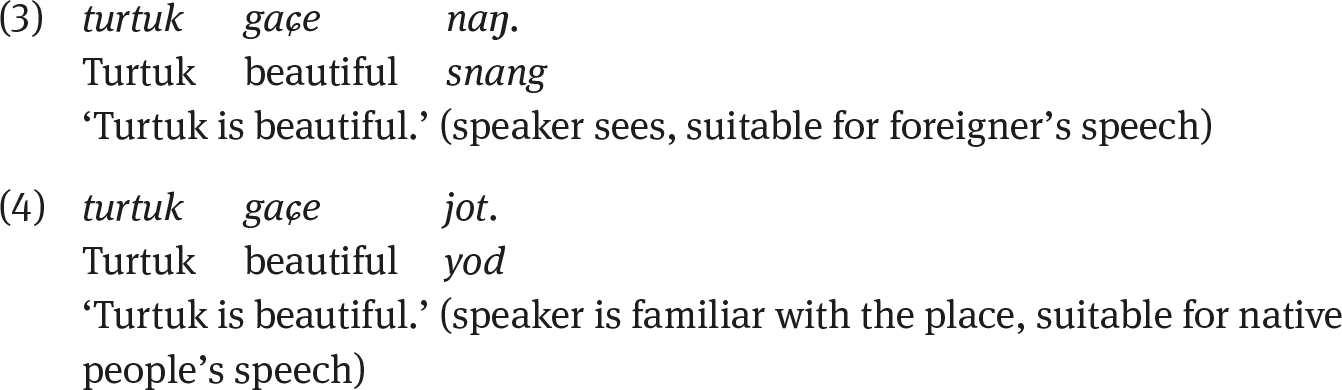

The next examples are naŋ and jot used in adjective clauses.27 In these examples, naŋ appears as an auxiliary verb following the adjectives. The consultant for this dialect added that example (3) is suitable for the speech of foreigners who come to Turtuk (a village where Balti is spoken) for the first time, and (4) is for the speech of native people who are familiar with the place.

naŋ can express both visual and non-visual evidence (smell, taste, feel), as in (5)–(8).

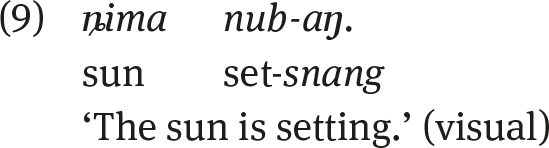

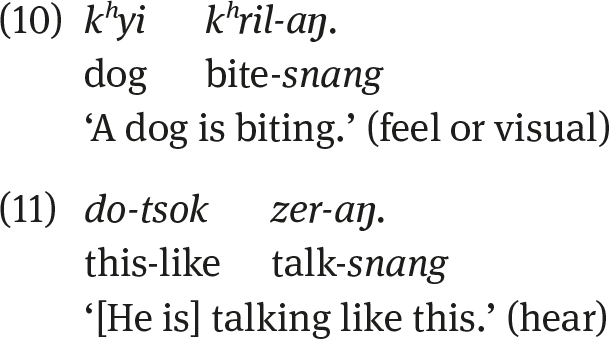

The following examples are naŋ and jot used in verb clauses. After a verb, naŋ appears as a suffix -aŋ, as in (9).

Example (10) is an expression used when the speaker knows that something is biting her because she can feel it, or sees a dog biting. Example (11) is an expression used when the speaker knows that someone is talking like this because she can hear it.

2.3.2Turtuk dialect of Balti

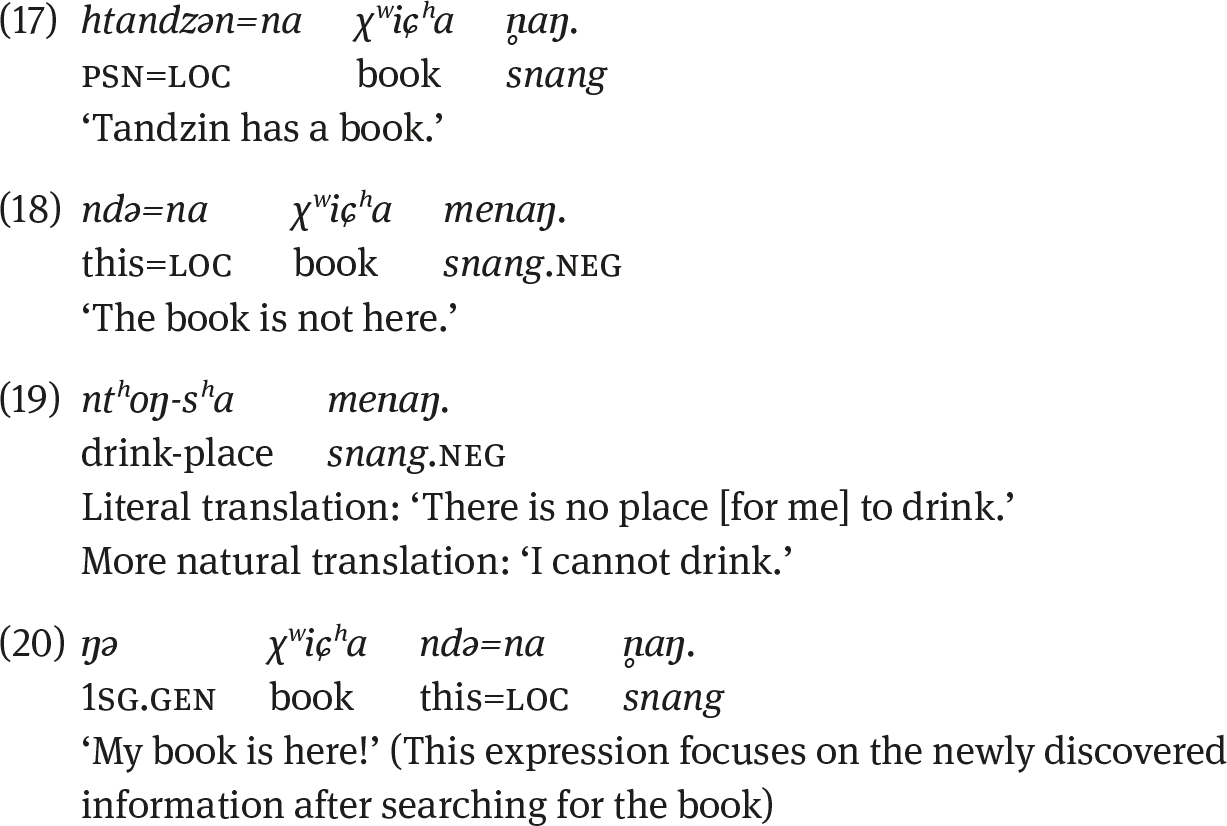

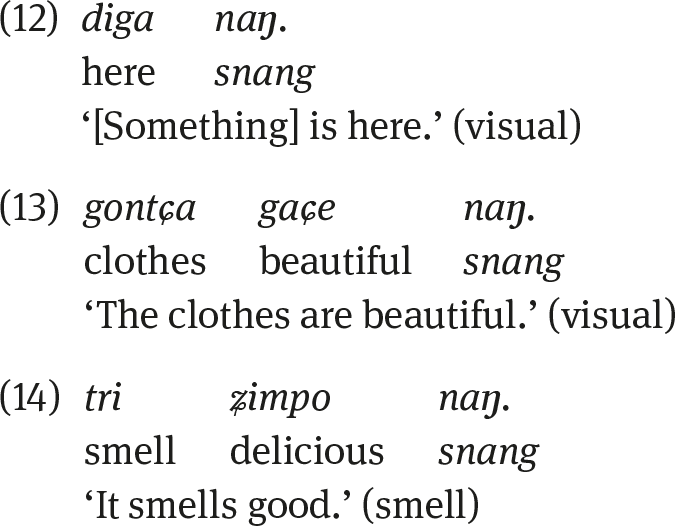

Turtuk is one of the Balti dialects spoken in North India. The Turtuk data are also taken from the present author’s field notes. In this dialect, naŋ (as well as its negative form meraŋ) is used to express sensory evidential (visual and non-visual). In contrast, jot (as well as its negative form met) is used to express speaker’s knowledge. naŋ is used as an existential verb, and an auxiliary in both adjective and verb clauses, as in (12)–(16).

Tab. 2: Existential Verbs in the Turtuk Dialect.

| Affirmative | Negative | |

| Sensory evidential | naŋ | meraŋ |

| Speaker’s knowledge | jot | met |

2.3.3Khaplu dialect of Balti

Khaplu (Khapalu) is one of the Balti dialects spoken in Pakistan. The Khaplu data are taken from Sprigg (2002), who wrote a Balti dictionary. Sprigg defines nang as ‘(seem to) be’ and met-nang as ‘(apparently) is not’ (Sprigg 2002: 113, 120). Sprigg (2002) does not provide further explanations or examples of nang and met-nang.

Tab. 3: Existential Verbs in Khaplu Dialect.

| Affirmative | Negative | |

| ‘(seem to) be’ | nang | met-nang |

| ‘be, is, are, exist, have’ | yot | met |

2.3.4Amdo Tibetan

Amdo Tibetan is spoken in the north-eastern part of Tibet. In Amdo Tibetan, snang is seldom used; the use of snang as an evidential verb is attested only in dPa’ ris [χwari] and Thewo.

2.3.4.1dPa’ ris dialect

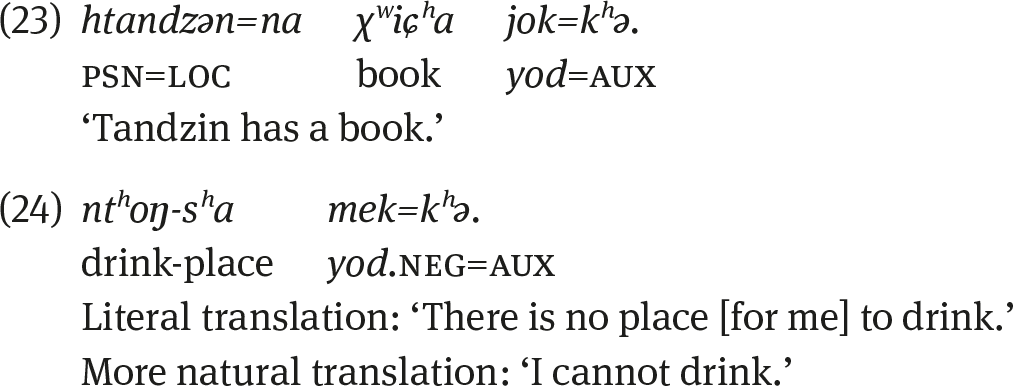

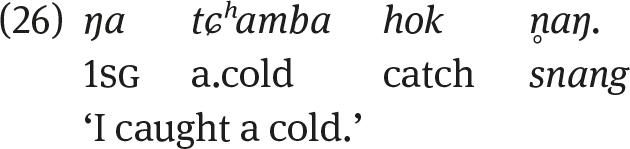

dPa’ ris is one of the dialects of Amdo Tibetan. This dialect is spoken in the northeastern end of the Qinghai-Tibet highlands. The dPa’ ris data are taken from Ebihara (2012: 153–156). In dPa’ ris, n̥aŋ (as well as its negative form menaŋ) is used as an existential verb (expressing existence and possession), and an auxiliary verb. n̥aŋ is mostly used in events concerning the third person (when the speaker does not know the person well), but in some cases is used for events concerning the first person (such as physical phenomena or newly discovered information). That is to say, these verbs are used for non-egophoric expressions, as in (17)–(20).

Another existential verb jol (as well as its negative form mel) is mostly used in events where the first person is relevant and questions the second person. That is to say, jol is used for egophoric expressions.

This verb jol can be followed by an auxiliary verb =kʰə ‘state, attribution,’ while jok =kʰə is used in the same situation as n̥aŋ. In my research, there is no difference between these two existential expressions, and they are interchangeable in all examples. Furthermore, in native speakers’ intuition they have the same functions.

These three series of existential expressions are summarized in Tab. 4 below.

Tab. 4: Existential Verbs in dPa’ ris Dialect.

| Affirmative | Negative | |

| Egophoric | jol | mel |

| Non-egophoric | n̥aŋ | menaŋ |

| jok=kʰə | mek=kʰə |

The verbs n̥aŋ/menaŋ are also used as part of the ‘progressive’ auxiliary verb (=kʰə n̥aŋ/=kʰə menaŋ), and a second part of verb serialization (V n̥aŋ/V menaŋ), as in (26).

2.3.4.2Thewo dialect

Tournadre and Jiatso (2001: 87) pointed out that nɔ̃ (WT: snang) is used in Thewo, corresponding to ’dug in Standard Tibetan. Unfortunately, this study does not demonstrate any sentence including snang.

2.3.5Kham Tibetan

Evidential snang is found in several Kham Tibetan dialects: Dongwang, rGyalthang, Bathang, Budy, and Zhollam. All of these dialects are spoken in southern Kham.

2.3.5.1Dongwang dialect

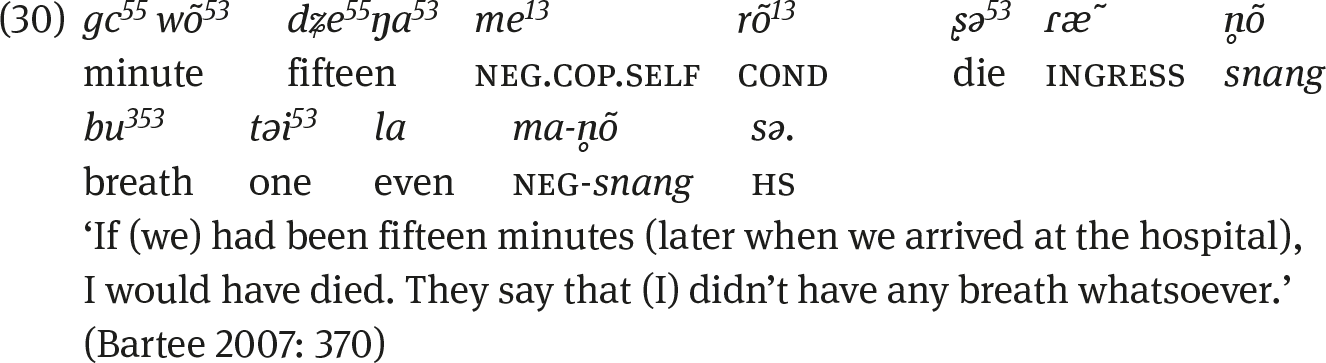

The Dongwang data are taken from Bartee (2007). In Dongwang n̥õ (as well as its negative form ma-n̥õ) expresses the “direct visual evidential (imperfective),” and contrasts with tʰi, which is the “visual evidential (perfective)” (Bartee 2007: 369/370). She says, “[t]he imperfective direct visual evidential n̥õ has likely arisen from WT <snang> ‘to feel’ or ‘to sense.’ It is used when the time of speech and the time of the event are identical” (2007: 369). First, she shows sentences with the third person and second person subject.

She then adds that “n̥õ sometimes occurs in clauses with non-control verbs and first person S or A argument,” and explains example (30) as follows.

In the portion of text expressed by (54)[=(30) in the present article], the speaker is relating events that had happened to her while she was unconscious. This is not like the mirative use of an evidential, as the hearsay in the third clause in (54) indicates that these events were related to her by others. Thus it is their visual knowledge that is being coded. (Bartee 2007: 370)

2.3.5.2rGyalthang dialect

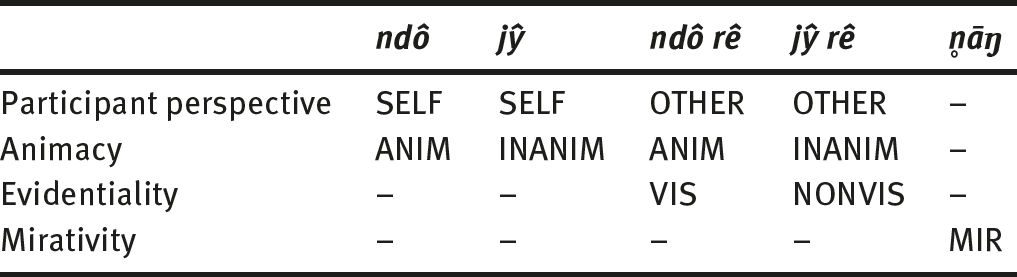

The rGyalthang data are taken from Hongladarom (2004, 2007). According to Hongladarom (2007: 26), the existential copula n̥āŋ marks the speaker’s new and unexpected knowledge (mirativity), and contrasts with other existential copulas: ndô, ndô rê, jŷ, jŷ rê. The dimensions of contrasts are summarized in Tab. 5.

Tab. 5: rGyalthang Existentials (Hongladarom 2007: 27).

2.3.5.3Bathang dialect

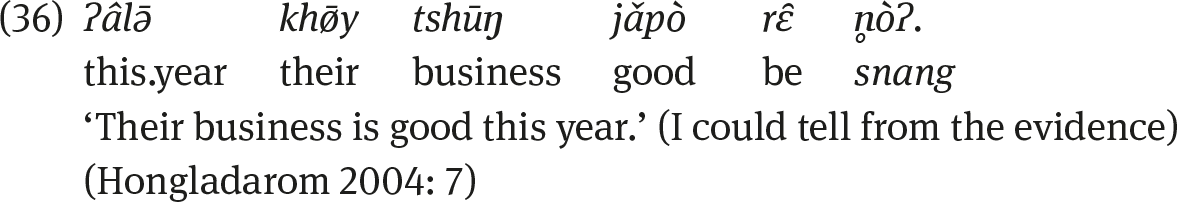

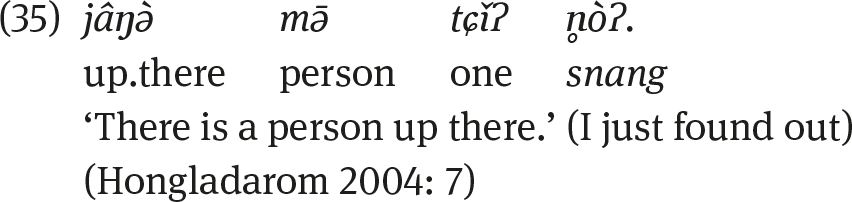

The Bathang data are taken from Hongladarom (2004). She mentions that the existential verb n̥òʔ marks a ‘specific, mirative statement’ and ‘inference’ when accompanying a ‘be’ verb (Hongladarom 2004: 7). Gesang and Gesang (2002: 89) give an example of snang in Bathang, but do not explain its specific meaning and function.

The first example marks the ‘mirative’ and the second is an example with combined ‘be+snang’ that marks ‘inference.’

2.3.5.4Budy dialect

The Budy data are taken from Suzuki (2006). He mentions that n̥õ marks “inference from the situation” (Suzuki 2006: 6).

2.3.5.5Zhollam dialect

The Zhollam dialect of Gagatang Tibetan is spoken in southern Kham. The Zhollam data are taken from Suzuki (2012).28 He mentions that n̥ɔŋ (as well as its negative form ´mi-n̥ɔŋ) is mainly employed as follows: (1) copulative usage: equational and/or identificational functions for non-self-oriented speech without any specific evidentiality (example (38)); (2) existential usage: for both the existence of the subject and the speaker’s intimate awareness of that existence (example (39)); (3) evidential usage as a verbal suffix: to represent the visual experience of a speech (examples (40) and (41)). He added that of these usages, the first usage is unique to the Zhollam dialect among the Tibetan dialects.

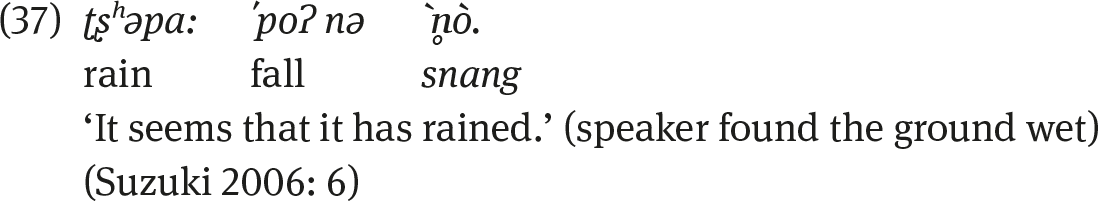

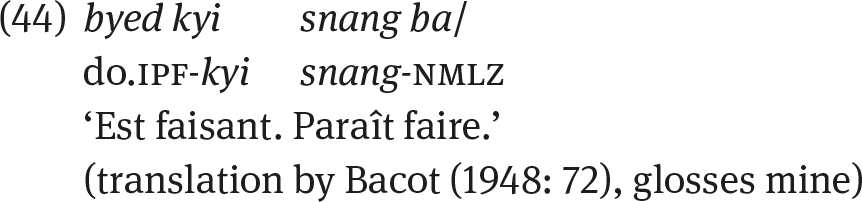

2.3.6Shar Tibetan

Suzuki and dKon mchog Tshe ring (2009) note the evidential use of snang in the sKyangtshang dialect of Shar Tibetan spoken in Songpan in the Sichuan province. In this dialect, ˚ʰnɔŋ is used as an existential verb (expressing existence and possession). In sentences with third person subjects, ˚ʰnɔŋ is used to indicate the speaker’s affirmation of the event, as in (42). When the other existential verb joʔ (WT yod) is used, inference based on a judgement of the situation is indicated, as in (43). Thus, speaker affirmation of ˚ʰnɔŋ contrasts with inference.

2.3.7Central Tibetan

Tournadre and Jiatso (2001: 85/86) point out that nāŋ (WT: snang) is used in four dialects: Reting, Nyimachangra, Drigung (Nomad), and Penpo, in Central Tibetan, corresponding to ’dug in standard Tibetan. Unfortunately, this study does not give any sentence including snang.

2.4snang in written Tibetan

Evidentiality in written Tibetan is difficult to attest. Some scholars insist that evidentiality is attested in neither Old Tibetan29 nor Classical Tibetan30 (Zeisler 2000: 40) and some scholars say that evidentiality is attested in written Tibetan (Hoshi 2010; Hill 2013; Takeuchi 2015 etc.). For example, Hoshi (2010) suggests the difference between yod and ’dug (sensory evidential) can be found in Rgyal rabs gsal ba’i me long.

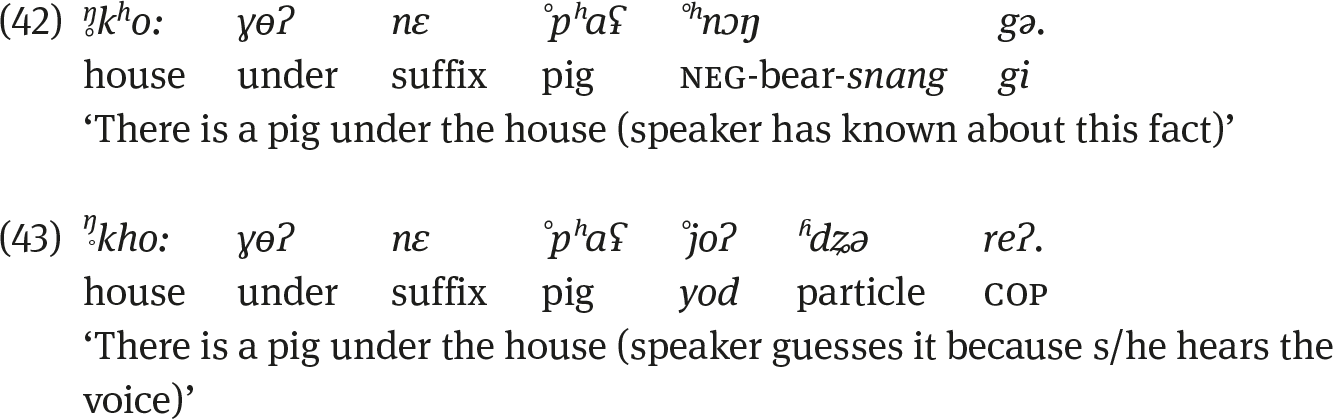

In the case of snang, although the existence of evidential snang is not clear in Written Tibetan, some scholars mention the evidential usage in Written Tibetan (Bacot 1948; Yamaguchi 1998). Bacot (1948: 72) defines the construction kyi snang ba (-kyi snang-nmlz) as ‘seems to.’ He provides the following example.

Yamaguchi (1998: 353) explains the constructions yin par snang (cop-nmlz.dat snang) and yod par snang (exist-nmlz.dat snang) in written Tibetan. He says these expressions have the same meaning as yin par ’dug (cop-nmlz.dat ’dug) and yod par ’dug (exist-nmlz.dat ’dug), which mark ‘inference.’ The following examples show the construction with snang used as ‘inference.’

When searching through texts, it is difficult to distinguish between the meanings ‘appear’ and ‘exist’ in Written Tibetan. For example, in the next example, which is from the Old Tibetan text of the treaty inscription of 821/822, Li and Coblin (1987: 79/80) translate snang as ‘appear,’ but it might also be interpreted as ‘exist.’

Regarding the use of snang in written Tibetan, it is interesting that in Rgyal rabs gsal ba’i me long (written in the 14th century), in his concluding remarks, the author mentions the policy of writing this book as follows:

snang skad dang/gda’ skad go dka’ ba rnams bcos te gsal bar byas/

‘The speech of snang and speech of gda’, which are not easily understood have been corrected and made clear.’ (the text is from Sa skya pa Bsod nams rgyal mtshan 1981, translation by the present author)

Both snang and gda’ are existential verbs and grammaticalized as evidential markers in spoken Tibetan dialects. gda’ is used in the Kham and Hor dialects (Tournadre and Jiatso 2001: 87). snang skad ‘speech of snang’ and gda’ skad ‘speech of gda’’ seem to be varieties of Tibetan with the final endings snang and gda’. Presumably, these expressions might be thought of as dialectal variations, and are thus considered not standard for Written Tibetan. The statement suggests the possible trace of snang as a verb ending in the 14th century.

2.5Conclusion

The evidential usages of snang in spoken and written Tibetan have been discussed above. We can see that evidential snang is widely used in modern Tibetan dialects. These areas are mapped in Fig. 1. It is worth noting that evidential snang ranges from the western to the eastern ends of the Tibetan speaking area. Geo-linguitsic analysis suggests that the use of evidential snang, which can be traced back to Old and Classical Tibetan, remains in the peripheral areas of Tibetan speaking area. As there is insufficient data regarding snang in Central Tibetan, its function is at present unclear, as is the reason for its isolated location in this area.

In the examples of several Tibetan dialects, we can see five evidential and evidential-like meanings/functions as shown below. The names of each dialect are mentioned in parentheses, though the meanings/functions in Thewo and five dialects of Central Tibetan are not clearly known. Speaker affirmation of snang in sKyangtshang, which contrasts with inference, does not show clear sources of information, and is thus not included in the following:

(i)Visual (Dongwang)

(ii)Sensory (Tyakshi, Turtuk, Khaplu)

(iii)Inferential (Budy)

(iv)Non-Egophoric (dPa’ ris, Zhollam)

(v)Mirative (rGyalthang, Bathang)

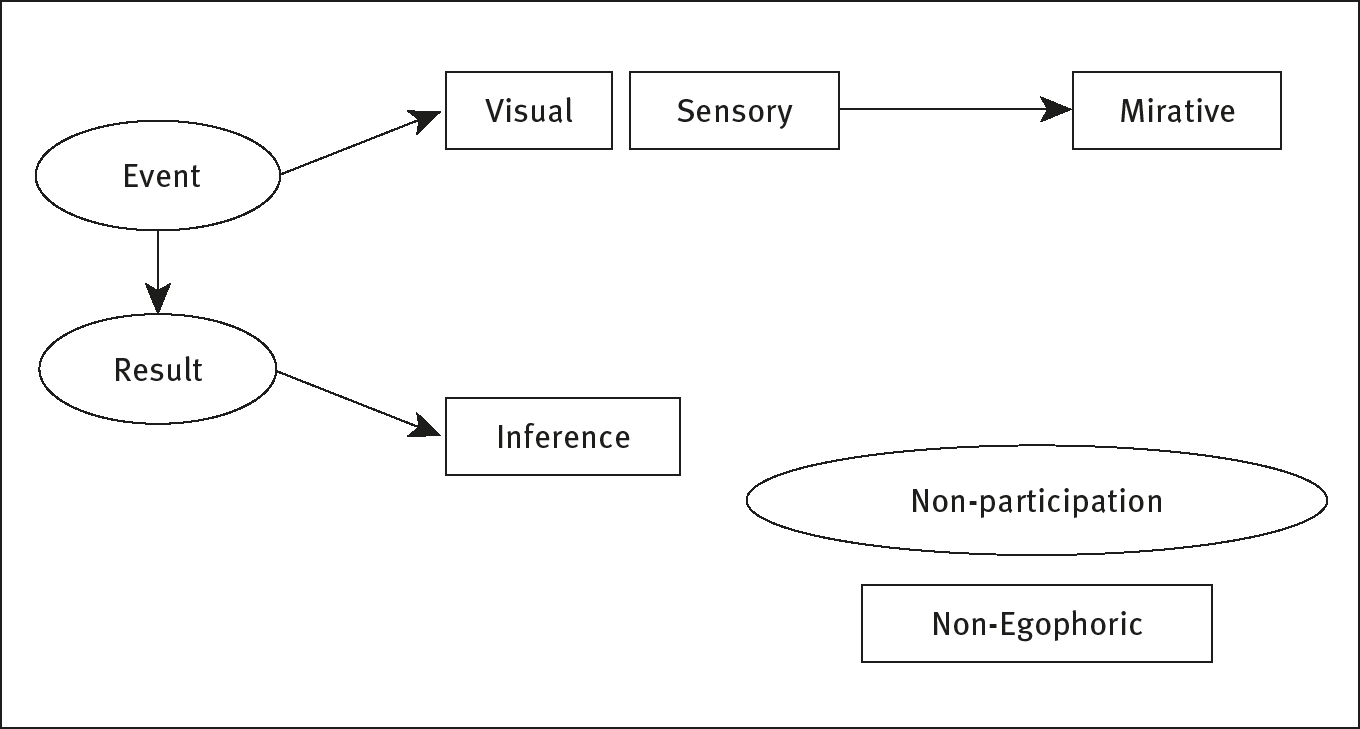

After examining the evidence of a variety of Tibetan dialects, I have arrived at a semantic map for the meanings/functions of evidential snang. The semantic map is “a method for describing and illuminating the patterns of multifunctionality of grammatical morphemes that does not imply a commitment to a particular choice among monosemic and polysemic analyses” (Haspelmath 2003: 212). This map is shown in Fig. 2. This diagram shows that visual and sensory meanings occur when the speaker sees the events, and the mirative then derives from these evidentials. Inference occurs when the speaker sees the result of the event. Lastly, the non-egophoric meaning has no participation in the event-result frame.

In this study, examples of Written Tibetan could not be fully investigated, so that more research is required on the usage of snang in written texts, particularly concerning constructions such as yod par snang, yin par snang, cing snang, gi snang, and V snang. Figure 1 shows us that the geographical distribution of evidential snang is quite widely ranging. This distribution might have some connection to the historical development of snang. It is desirable that from this distribution, research on Written Tibetan will make the historical development and grammaticalization process of evidential snang clear in future.

Acknowledgments: Great thanks go to the consultants of Balti and Amdo Tibetan. This study is based on my presentation in the panel on Tibetan Evidentiality at the 24th conference of SEALS. I also thank the organizers and participants of the panel. I am grateful for many comments in the presentation, which were helpful for revising this chapter. In particular, Nicholas Tournadre and Hiroyuki Suzuki suggested useful resources for this study. Izumi Hoshi and Satoko Shirai also gave me valuable advice.

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science “Formation of the oldest layer of Tibetan and its formational transition” headed by Tsuguhito Takeuchi (2012–2017, project number 24242015), Linguistic Dynamics Science Project 2 (project for building an international network of collaborative research on endangered linguistic diversity) headed by Toshihide Nakayama.

Abbreviations

1 first person, 2 second person, 3 third person, ABS absolutive, AUX auxiliary verb, COND conditional, CONT continuative, COP copula, DAT dative, ERG ergative, GEN genitive, HON honorific, HS hearsay, IMP imperative, IPF imperfective, LOC locative, NEG negative, NMLZ nominalizer, PF perfective, PL plural, PSN personal name, Q question, SELF self, SFP sentence, final particle, sg singular, TOP topicalizer, VBZR verbalizer, WT Written Tibetan

- Affix boundary ; = Clitic boundary

References

Agha, Asif. 1993. Structural form and utterance context in Lhasa Tibetan: Grammar and indexicality in a non-configurational language. New York: Peter Lang.

Aikenvald, Alexandra Y. 2004. Evidentiality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bacot, Jacques. 1948. Grammaire du Tibétain littéraire. Paris: Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient.

Bartee, Ellen. 2007. A grammar of Dongwang Tibetan, University of California, Santa Barbara doctoral dissertation.

Bielmeier, Roland. 1985. Das Märchen vom Prinzen Čobzaṅ. Eine tibetische Erzählung aus Baltistan. Text, Übersetzung, Grammatik und westtibetisch vergleichendes Glossar. (Beiträge zur tibetischen Erzählforschung, 6.) St. Augustin: VGH Wissenschaftsverlag.

DeLancey, Scott. 1986. Evidentiality and volitionality in Tibetan. In Wallace Chafe & Johanna Nichols (eds.), Evidentiality: The linguistic coding of epistemology, 203–213. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Ebihara, Shiho. 2012. Preliminary field report on dPa’ris dialect of Amdo Tibetan. In Tsuguhito Takeuchi & Norihiko Hayashi (eds.), Historical Development of the Tibetan Languages: Proceedings of the Workshop B of the 17th Himalayan Languages Symposium, 149–161. Kobe: Kobe City University of Foreign Studies.

Garrett, Edward. 2001. Evidentiality and assertion in Tibetan. University of California, Los Angeles doctoral dissertation.

Ge sang Ju mian & Ge sang Yang jing 格桑局冕 & 格桑央京. 2002. Zangyu fangyan gailun 《藏语方言概论》 [An introduction to Tibetan dialects]. Beijing: Minzu Chubanshe 民族出版社.

Haspelmath, Martin. 2003. The geometry of grammatical meaning: Semantic maps and crosslinguistic comparison. In Michael Tomasello (ed.), The new psychology of language, vol. 2, 211–242. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Häsler, Katrin Louise. 1999. A grammar of the Tibetan Dege (Sdege) dialect. University of Bern doctoral dissertation.

Hill, Nathan. 2012. “Mirativity” does not exist: ḥdug in “Lhasa” Tibetan and other suspects. Linguistic Typology 16(3). 389–433.

Hill, Nathan. 2013. ḥdug as a testimonial marker in Classical and Old Tibetan. Himalayan Linguistics 12(1). 1–16.

Hongladarom, Krisadawan. 1994. Historical development of the Tibetan evidential tuu. Paper presented at the Tibetan linguistics workshop, 26th international conference on Sino-Tibetan languages and linguistics, October, National museum of ethnology: Osaka, Japan.

Hongladarom, Krisadawan. 2004. Development of evidentials in various dialects of Kham Tibetan. Paper presented at the Evidentiality workshop, September 30, organized concurrently with the 37th International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics, University of Lund, Sweden.

Hongladarom, Krisadawan. 2007. Evidentiality in Rgyalthang Tibetan. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area, 30(2). 17–44.

Hoshi, Izumi 星泉. 1997. Chibettogo Rasahōgenniokeru jutsugono imino kijutsuteki kenkyū 《チベット語ラサ方言における述語の意味の記述的研究》 [Descriptive study on meanings of predicates in Lhasa dialect of Tibetan]. Tokyo University doctoral dissertation.

Hoshi, Izumi 星泉. 2010. 14 seiki Chibettogobunken ōtōmeijikyōniokeru Sonzaidōshi 14 世紀チベット語文献『王統明示鏡』における存在動詞 [Existential Verbs in the Rgyal-rabs Gsal-ba’i Me-long, a 14th century Tibetan narrative]. Tokyo University Linguistic Papers 29. 29–68.

Jäschke, H. A. 1949 [1881]. A Tibetan-English dictionary. London: Lowe and Brydone.

Koshal, Sanyukta. 1979. Ladakhi Grammar. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Li, Fang Kuei & Coblin, South W. 1987. A study of the old Tibetan inscriptions. Taipei: Institute of history and philology, Academia Sinica.

Norman, Rebecca. 2001. Getting Started in Ladakhi. (2nd edition). Leh: Melong Publications.

Rangan, K. 1979. Purik Grammar. Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Languages.

Read, Alfred F. C. 1934. Balti Grammar. London: Royal Asiatic Society.

Róna-Tas, A. 1966. Tibeto-Mongolica: the Tibetan loanwords of Monguor and the development of the archaic Tibetan dialects. The Hague: Mouton.

Sa skya pa Bsod nams rgyal mtshan. 1981. Rgyal rabs gsal ba’i me long. Beijing, Mi rigs dpe skrun khang.

Sprigg, Richard Keith. 2002. Balti-English English-Balti dictionary. Richmond: Routledge Curzon.

Suzuki, Hiroyuki 鈴木博之. 2006. Senseiminzokusōrō Chibettogo shohōgenniokeru snangno imi 川西民族走廊•チベット語諸方言におけるsnangの意味 [The meaning of snang in Tibetan dialects of the ethnic corridor in West Sichuan]. Paper presented at the 9th meeting of Tibeto-Burman Linguistic Circle, July 17, Kyoto University, Japan.

Suzuki, Hiroyuki. 2012. Multiple usages of the verb ‘snang’ in Gagatang Tibetan (Weixi, Yunnan). Himalayan Linguistics, 11(1). 1–16.

Suzuki, Hiroyuki & dKon mchog Tshe ring 鈴木博之•供邱澤仁 2009. Hyaru Chibettogo Songpan Shanba [sKyangtshang] hōgenniokeru snangno yōhō ヒャルチベット語松潘•山巴[sKyangtshang] 方言におけるsnangの用法 [The Usage of snang in Songpan sKyangtshang dialect of Shar Tibetan]. In Onishi, Masayuki 大西正幸 & Kazuya Inagaki 稲垣和也 (eds.) Chikyūken Gengo Kijutsu Ronshū《地球研言語記述論集》1. 123–132.

Takeuchi, Tsuguhito. 2015. The function of auxiliary verbs in Tibetan predicates and their historical development. Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, 31. 401–415.

Tournadre, Nicholas. 1996. L’ergativité en Tibétain: Approche morphosyntaxique de la langue parlée. Leuven: Peeters.

Tournadre, Nicholas & Konchok Jiatso. 2001. Final auxiliary verbs in literary Tibetan and in the dialects. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 24(1). 49–111.

Yamaguchi, Zuihō 山口瑞鳳. 1998. Chibettogo bungo bunpō 《チベット語文語文法》 [Grammar of written Tibetan]. Tokyo: Shunjūsha 春秋社.

Yukawa, Yasutoshi 湯川恭敏. 1966. Chibettogono duu no imi チベット語のduuの意味 [The meaning of Tibetan duu]. Gengo Kenkyū 《言語研究》 [Journal of the Linguistic Society of Japan] 49. 77–84.

Zeisler, Bettina. 2000. Narrative conventions in Tibetan languages. The issue of mirativity. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area, 23(2). 39–77.