I didn’t understand what school was for. A lot of the teachers thought I was thick. I remember the head teacher saying I’d never make anything of myself in front of the whole school. My ability to learn in school had been pretty much crushed out of me quite young. I still feel scared when I hear that word, ‘thick’.

Jack Dee, comedian

What we want for our children

We talk to lots of people about schools – teachers, parents, children and many others – and we think we have a shrewd idea about what is on people’s minds. So here is what we are assuming about you, our readers. We know that you want the best for your children – your own and the ones you may teach. We think that means, roughly, that you want them to be happy, to lead lives that are rich and fulfilling, to grow up to be kind and loving partners and loyal friends, and to be free from poverty and fear. We assume this means having a job that is satisfying and makes a decent living. We guess you don’t want your children to be as rich as Croesus if that brings with it being miserable, greedy or anxious.

We also suspect that you did not decide to have a child so that they could contribute to the economic prosperity of the country and become ‘productive members of a world-class workforce’. We don’t imagine that you think about your son or daughter, or the children you teach, as if they were pawns in a national economic policy or in a sociological quest for equity or upward mobility. (We reckon that you know people, as we do, who have real doubts about the idea that the more you make and spend the happier you will be, and who may even have down-sized in order to live in a way that feels more worthwhile or morally satisfying. There are plenty of happy plumbers with good degrees these days.)

And we assume that you would like your child’s school to support you in those general aims. The aims of school do have to be general because we just can’t know what kind of work and lifestyle will ‘deliver’ that quality of life for any individual. Children’s lives will take many twists and turns, as yours and ours have, and whether they turn out to be accountants in Auckland, teachers in Namibia or shepherdesses in Yorkshire, we will want them to have the same general qualities of cheerfulness, kindness, open-mindedness and fulfilment, won’t we? (Please insert your own favourite words to describe those deepest wishes for your children here.)

We suspect that you might still be touched, as we are, by these words on children from Khalil Gibran’s book The Prophet (much quoted though they may be):

Your children are not your children.

They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself.

They come through you but not from you,

And though they are with you yet they belong not to you.

You may give them your love but not your thoughts,

For they have their own thoughts.

You may house their bodies but not their souls,

For their souls dwell in the house of tomorrow,

Which you cannot visit, not even in your dreams.

You may strive to be like them,

But seek not to make them like you.

For life goes not backward nor tarries with yesterday.1

If your household is full of ‘digital natives’, doing all kinds of wonderful and scary things on social and digital media – or you have ever watched a TV show called Outnumbered – you will be in no doubt that “their souls dwell in the house of tomorrow”! A mutual friend of ours was telling us, just the other day, about a conversation with his granddaughter, Edie, who is 12. She was doing something with her mobile phone and Martin asked her what it was. She showed him the app she had discovered for learning Japanese, which she had decided she would teach herself. Often in bed at night she would be listening and practising quietly, under the bedclothes. Her parents hadn’t a clue what she was up to – she had not felt the need to tell them – and her teachers, earnestly trying to get her to write small essays on ‘the functions of the computer mouse’, certainly had no idea. Will Edie be working in the Tokyo branch of Ernst & Young in 15 years’ time? Who knows.

We make the assumption that you are doing your best to help your children get ready for whatever comes along, both at home and at school, and preferably both together. If you have children of your own at school, we assume you would like the school to be your partner in this crucial enterprise. And if you are a teacher, we assume that you take immense pride in the amazing job you have: helping to launch the lives of hundreds of children in the best way you know how. We are all angling the launch pad, so to speak, so that – whatever they are going to be – they get the best possible send-off. Whether you are helping little ones learn how to tell the time and ‘play nicely’, or bright 17-year-olds to grapple with A level English or the International Baccalaureate’s theory of knowledge module, we’ll assume you don’t want to take your eye off that fundamental intention of getting them ready for life. What could possibly be a more fulfilling way of earning a living?

All is not well

However, we are also going to imagine that you, like us, have some serious misgivings about what is actually happening in schools. In the boxes scattered throughout the next few pages, and later in the book, there are some stories and quotations from children, their parents and teachers. We’ve put them there to see if you share some of the same feelings and experiences. The schools and the people we talked to are all real but, in most cases, we’ve changed or removed their names to protect their anonymity.

I’d loved my primary school, but at St Bede’s Comprehensive School I felt depressed and scared, like a wild animal in a cage. I felt empty inside. I was ill once for two weeks, I felt wiped out and tired; but mentally I felt happy because of not being at school. When I returned, however, after just one day I came home and felt restless, confused, my mind couldn’t focus on one thing at a time. I felt unsettled and one tiny thing would make me flip into tears.

If ever the teacher was challenged by a pupil about what they said, the pupil would get told off. I got told off for telling the teacher that a boy was teasing me by saying he liked to kill animals, when we were on the subject of animal cruelty. She said to me, “Now that was a stupid thing to say wasn’t it?” – what I’d said, not the boy. I looked at her – why in the world would that be stupid? I raised my hand again. I wanted to say something that sounded strong. But when she said, “Have you got something sensible to say now?” I felt the gaze of all my classmates on my back, and I lost my nerve as tears filled my eyes and clogged my throat. “No,” I said.

I felt resentful but couldn’t bring myself to become a rebel. So I became quiet and my normal self was glazed over by someone different – who I didn’t like. There was no room at St Bede’s for someone different like me. And I felt myself turning into some fashion freak like everyone else. I hated it because keeping my feelings to myself is very hard. Because normally they’re very strong. I was always hiding myself while I battled through the day.

I had to let my feelings out, but I couldn’t wait to tell mum at the end of the day, so I turned to my friend Leanne who was good at talking about sensitive subjects. When I did she would always try to help me fix them – until one day she said, “Look, Annie, I know you’re not enjoying it, but I am and I don’t really want to talk about it because it’s not positive.” Then I had no one to talk to.

That was another thing about St Bede’s. You were told to “Stop being childish”, but we were children so we had to be childish! We weren’t allowed to run about at break-time. This was one of the things I found utterly stupid. There was a boy in my class that was always bouncing in his seat and shouting out because of this. He had never been like that before [at primary school].

Annie, Year 7 student,

St Bede’s Comprehensive School

What are your concerns about the schooling you are providing (if you are a teacher) or your child is getting (if you are a parent)? Of course, many children thrive in school, if they are lucky enough to find one that suits them. They retain their cheerfulness and gentleness, enjoy maths and English, find a sport and a musical instrument they love to play and practice, and are helped to discover and explore the interests and aptitudes that may grow into the basis of a degree and a career. (Though even conspicuous successes like Tom, on page 8, can have their misgivings.)

But many don’t. A lot of parents and teachers see their ‘bright’ children becoming anxiously fixated on grades and losing the adventurous, enquiring spirit they had when they were small. They study because ‘it is going to be on the test’, not because it is interesting or useful. Or adults see their ‘less able’ children (we’ll query this kind of terminology later on) becoming ashamed of their constant inability to do what is required, and so becoming either actively resistant to school or passive and invisible. Both ends of the achievement spectrum can experience a curious but intense mixture of stress and boredom. The obsession with grades and test scores turns some children into conservative and docile ‘winners’ at the examination game. Many muddle by in the middle, willing to play a game they don’t fully understand.

And some children grow into defeated ‘losers’. Yet these losers (like the talented Jack Dee) are not inherently stupid or lazy. Research shows that they have the potential for highly intelligent and determined problem-solving in real-life settings, but some of them, tragically, have had the learning stuffing knocked out of them by their experience at school, and as a result they are less happy, less creative and less successful than they could be. That is not giving them the best, and it is not nurturing the talent and the grit that would help them to be happy people and thoughtful citizens. Many people’s concerns about school centre on the validity of the examination system, and on the effect that the focus on tests and exams had on them or is having on their children.

For many young people the stressful nature of school is compounded by the sheer pointlessness of much of what they are expected to learn. It is a rare parent (or teacher) who is able to come up with a convincing reason why every 15-year-old needs to know the difference between metamorphic and igneous rocks or to explain the subplots in Othello. Parents often find themselves trapped in a conflict between sympathising with their children about the apparent irrelevance of much of the curriculum and still trying to make them study it. Certainly up to GCSE there is a fear that, if children don’t do their best to knuckle down and ‘get the grades’, their life choices will be forever narrowed and blighted. And, under the present antiquated system, they are quite right to be concerned. The horns of this particular dilemma are sharp and painful.

Teachers may have other quandaries – for example, wanting to impart to their students their own love of reading and literature, and knowing, from bitter experience, that the effect on many 15-year-olds of having to study The Tempest or Jane Eyre is exactly the opposite. Not everyone is brave (or foolish) enough to be the charismatic, rebellious Robin Williams character (John Keating) from Dead Poets Society, or Hector (Richard Griffiths) from The History Boys. Politicians who blithely tinker with the set books rarely spend longer in a school than it takes for the photo opportunity to be secured, so have no conception of the damage and distress their doctrinaire beliefs and prejudices may be causing. Many teachers are caught between the rock of their own values and passions and the hard place of examination requirements.

My school gave me a great education really. I gained good GCSEs and A levels. I was always involved in the school plays and drama competitions, winning several times. I took part in a host of extra-curricular activities and, as head boy, I had opportunities to speak publically on local, national and international platforms. Yet when I arrived at Oxford, I found myself shying away from the drama societies, the debates and even whole-hearted participation in my course – things that I would have loved and done naturally at school. What was missing? Why did my outlook change so drastically?

I think it was because, as a ‘gifted’ student, I was constantly protected from risk. Academic learning came naturally to me, so I never experienced real difficulty and was allowed to glide happily and successfully through school. Although excellent in many ways, my education allowed me – almost encouraged me – to develop an aversion to risk and failure. To this day I still cannot ride a bike. As a child I tried once – I fell off, it hurt – and I didn’t see the point of getting on again. I still stubbornly refuse to learn about car maintenance and electrics, and anything else I see as outside my realms of understanding. How different my life might have been if my school (as many now do) had deliberately nurtured an appetite for adventure and a tolerance for error!

Of course, young people need knowledge: no one is arguing against that. But they need more – they need the habits of mind that will allow them to become adaptive, responsive and caring people. And, as educators, I now see that we have the power to help them with this – or to hinder them completely.

Tom Middlehurst,

head of research at SSAT (The Schools Network)

For Tom there is a real feeling of having been rendered conservative and brittle by his, apparently successful, education. It was the same for Bill who went to Oxford to study English literature, where he discovered he had been taught how to outwit the A level examiner rather than to work his way into a difficult novel or poem and then articulate his own opinions.

For other people (like Annie’s mum, who sent us her daughter’s sad reflections) their worries are more about a school culture that is callous or indifferent to their children’s feelings, interests and anxieties. It’s no use telling Annie to ‘buck up’ and ‘stop being babyish’. She has a perfect right to her own, rather mature, concerns about animal cruelty. If she is being told to ‘toughen up’, and to deny her own moral sensibilities, then her teacher is unreasonably taking sides in a serious ethical debate, and Annie is being told that her qualms and reactions are invalid. Many parents see their kind, sensitive children being brutalised by the culture of school. Bullying does not need to be overt and physical, although it often is. Children can be very unkind and cliquish, and it is the job of adults to moderate those effects. Annie certainly should not feel she has to become a “fashion freak” in order to have any friends. She is trying to toughen up and hold her ground, but when you are 11 you can do with some support.

Annie was lucky not to go down the same route as Chloe who started self-harming when she was just 12 as a way of coping with being unhappy at school. In an interview in The Independent in October 2013, Chloe says, “One day in class I dug my nails into my arm to stop me crying, and I was surprised by how much the physical pain distracted me from the emotional pain. Before long I was regularly scratching myself, deeper each time.” In 2012–2013, over 5,000 10 to 14-year-olds were treated by the NHS for self-harm, a rise of 20% on the previous year. Many of their worries stemmed from school.2

Here are another couple of experiences.

My daughter was like some spirally shape that was being pushed into a square box, and it was soul destroying. I’d take this gorgeous little girl to school, and then I’d pick up this really deflated person. She’s quite creative and dreamy. She’d look out the window, see a cloud and make up a story, but the teachers would shout at her to focus on her work … She became more insecure, more deflated, she cried more. She’d always been a good sleeper – she started waking at night. She became much less confident. She gets so over-tired by the workload that she kind of zones out. So she’s not having much happy awake time … and that’s no way to live.

Sandy, mother of a child now

in a London secondary school

As a parent you want your child to feel happy, safe emotionally, to enjoy themselves. When you see your child going into negative spirals, it is highly exhausting … What really did it for me was when she was looking out of the window, looking devastated, and she saw a rock that had cracked, and she said, “That’s how I feel; I’m broken inside.”

Pippa, mother of a Year 5 girl

in a London primary school

Some other views

School leavers ‘unable to function in the workplace’

More than four in 10 employers are being forced to provide remedial training in English, maths and IT amid concerns teenagers are leaving school lacking basic skills, it emerged today.3

It’s not just parents (and many teachers) who are unhappy with the schooling system. Variants of the headline above can be found in many British newspapers today as employers find that the ‘residues’ with which young people emerge from school at 16 or 19 do not include the necessary basic skills to cope in the workplace. In 2012, the employers’ organisation, the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), produced a thoughtful report, First Steps: A New Approach For Our Schools. In it they articulate two strong arguments.

The first calls for the development of a clear, widely owned and stable statement of the outcomes that all schools are committed to delivering. These, the report argues, should “go beyond the merely academic, into the behaviours and attitudes schools should foster in everything they do”.4 This statement should be the benchmark against which we judge all new policy ideas, schools and the structures we set up to monitor them. Are there good reasons for supposing that these modifications will enhance the desired outcomes? If not, go back to the drawing board. The report notes that “in the UK we have often set out aspirational goals [for education] … but we have rarely been clear about how the system will deliver them”, or about how they are to be assessed. “[D]elivery has been judged by an institutional measure – exam results – that is often not well linked to the goals set out at the political level.”5

The second concern in First Steps is the conspicuous lack of engagement by parents and the wider community in schooling. If parents do not feel that they are involved in a partnership with a school that has their child’s best interests at heart, or are not confident that they have a shared understanding of what those best interests are, children’s education is bound to suffer. Professor John Hattie’s research, which the report quotes, has shown that “the effect of parental engagement over a student’s school career is equivalent to adding an extra two to three years to that student’s education”.6 There is a consequent call for the adoption by schools of a strategy for fostering parental engagement and wider community involvement, including links with business. We’ll go more deeply into the CBI’s thoughtful argument about how schools need to change in Chapter 5.

It is worth noting that this call for schools to do more in the way of developing habits and attitudes, and engaging with communities, is not coming from fringe groups of ‘swivel-eyed loons’ or ‘bleeding-heart liberals’. It is coming from one of the most hard-nosed, well-informed organisations in British culture. They are certainly not members of what previous Secretary of State for Education Michael Gove so dismissively referred to as ‘The Blob’ – a hundred senior education scholars who have devoted much of their lives to trying to understand and improve a really complex system rather than settling for simplistic and antiquated nostrums.

Indeed, within the professional circles of people who know and care about the state of our schools, there is almost universal concern – not because they are politically extreme in any direction but because they know, first hand, what a mixed blessing education can turn out to be. Many school leaders, for example, are not happy with the status quo. Two current campaigns are illustrative of this. The first is called the Great Education Debate, led by one of the two main head teacher professional associations, the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL). The other is called Redesigning Schooling, led by The Schools Network (the organisation of which Tom Middlehurst is director of research). We explore these ideas in more detail in Chapter 5. You can decide for yourselves whether what they are saying mirrors your own concerns.

University departments and colleges of education are full of people trying to improve the lot of your children. Of course, some of them may have strange or radical ideas about what this means, but many are serious scholars who try to see more deeply, and read the evidence more dispassionately, than politicians and journalists are prone to do.

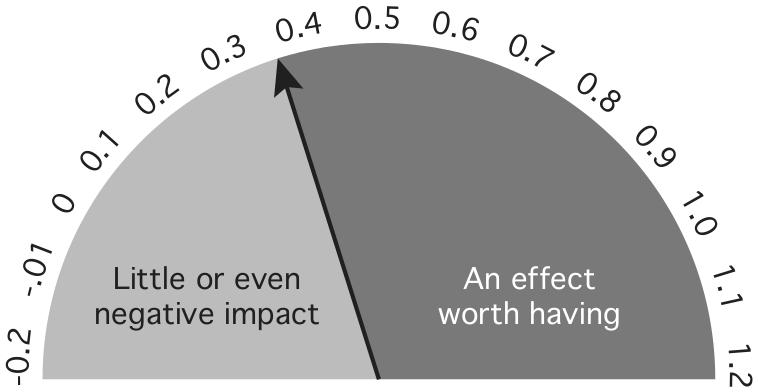

John Hattie has recently been hugely successful at making complex research accessible to teachers. This has been achieved partly through his painstaking analysis of the research, partly by lucid writing, and especially by using simple ‘dashboard’ images, like the one opposite, which make it very easy to compare the size of the effect that different teaching methods have on students’ examination performance. (Statistically, any effect size above 0.4 on the scale is worth having. Below that, the benefits for students’ achievements are trivial or even sometimes negative.)

Understanding effect sizes

His work has generated some surprises. According to the research, grouping students by ‘ability’ – the kind of setting that traditionalists like so much – has an effect size of just 0.12.7 Top sets benefit a little, while lower sets do worse than they would if they had not been segregated. If you care about everyone, not just the designated ‘winners’, this is an inconvenient truth. Reducing class sizes from 30 to 20 has almost no effect – and it is very expensive – unless, that is, you take this reduction as an opportunity to teach in a different way. Carry on teaching the 20 in the same way you taught the 30 and you might just as well set fire to a big pile of £20 notes. It is the nature of teaching itself that makes the big difference, not tinkering with structural features like the way children are batched, but you would never learn that from most of what passes for debate in the media and in parliament.

Some common issues

There are a wide variety of issues that concern parents, educators and employers more broadly. In different ways, and with different emphases, parents and employers share a host of concerns about the big issues besetting us today, many of which raise questions about education. These include such questions as:

● If the internet is both a force for good and for innovation, and an unreliable source of information and fraught with opportunities for cyber-bullying, how should we regulate and educate young people to be both safe and adventurous?

● Do we have to accept that the decline of reading for pleasure is the result of living in an e-world? How should schools balance surfing and gaming with the encouragement to get lost for hours in a gripping book?

● Are children, at root, ‘little savages’, inherently naughty and lazy, as some of the Victorians believed, who just have to be trained and disciplined, made to do boring and difficult things that seem pointless, and punished if they don’t comply ‘for their own good’, in order to civilise them? Or do they learn self-control better in other, less draconian, ways?

● How can we promote religious tolerance in an increasingly war-scarred world? What can schools do to immunise young people against the torrent of violent propaganda they can find on the web at a click of a mouse?

● Is climate change an inconvenient fact requiring us to change our habits, or an example of bad science? Is fiddling around trying to ‘balance’ chemical equations a necessary preliminary to engaging with this question, or a distraction?

There is a huge amount of discussion and debate about education these days. Much of it quickly gets technical and statistical and becomes hard to follow; and much of it is fuelled by passionately held beliefs, largely based on ‘what worked (or didn’t work) for me’, generating more heat than light. We all have views because we all went to school, so we think we are experts on the topic. We are all – or nearly all – honourable, well-meaning people who wish the best for the children in our care. But we can’t all be right. Should we go back to the past, to strict discipline and three-hour written exams, to hard subjects like Latin and algebra that train children’s minds in the arts of rationality and retention? Or should we push on to a new future of demanding project work and self-expression, collaboration and problem-solving, continuous assessment and portfolios?

Both of us remember at school having to learn a long poem by Macaulay about a battle for a Roman bridge. One stanza went:

It feels like that in the battle for education at the moment. Let’s take a closer look at what the battling forces believe: what is inscribed on their different ‘standards’.

1 Khalil Gibran, On Children, in The Prophet (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1923).

2 Kate Hilpern, Why do children self-harm?, The Independent (8 October 2013). Available at: http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/

health-and-families/features/why-do-so-many-

children-selfharm-8864861.html.

3 Graeme Paton, School leavers ‘unable to function in the workplace’, The Telegraph (11 June 2012). Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/education

/educationnews/9322525/School-leavers-

unable-to-function-in-the-workplace.html.

4 CBI, First Steps: A New Approach For Our Schools (London: CBI, 2012). Available at: http://www.cbi.org.uk/media/1845483/

cbi_education_report_191112.pdf.

5 CBI, First Steps.

6 John Hattie, Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement (London: Routledge, 2008).

7 See Hattie, Visible Learning.