The future is already here — it’s just not very evenly distributed.

William Gibson

So far we’ve painted a picture of schools which may be rather different from the one with which you are familiar. If you are a teacher or parent you may have laughed (or cried) out loud at the gap between what we are imagining and the experience you are having of your children’s school. Similarly, if you are reading this wearing your employer’s hat you may be wondering if we are inhabiting the same world as you do, where job applicants regularly show an alarming lack of basic literacy and numeracy, or even basic aspects of self-organisation.

Or perhaps neither of these imaginary reactions is accurate. Maybe you know schools that are doing much of what we are talking about. Or perhaps you are an employer who has developed a great relationship with local schools and are in active discussions about how the kinds of broader attributes we describe can best be developed. Whatever your response, in this chapter we want to offer you hope; to show you that, as William Gibson suggests, if you look around, you can see many examples of the future of schooling, even if they are not yet locally available for you. Many of them are drawn from schools which have been using approaches to teaching and learning like BLP.

At school I used to be a good learner but now in my opinion I am a brilliant learner! I have found a part of me where I can just get on and do what I need to do. For example, I always check my work through. Even now I still make mistakes in my work but I edit it and it comes out a lot better than I thought it would. Since BLP I’m more patient, and I have learned that listening to other children helps me too.

Kieran, Year 6

BLP not only helps me, but it helps others around me. I have a little sister who is 4 years old and goes to a primary school without BLP. When I use phrases like, “What did you learn?” and “Did you use questioning?”, that really helps her to understand what she is learning about and how it’s helping her in other situations – not just the one she’s in at school. When she’s reading something she can now persevere if she doesn’t understand, and if she doesn’t understand a topic at school, she’ll say, “Well, I have used … to overcome this situation.” It helps you to become your own learner.

Victoria, Year 9

I used to get embarrassed and not like talking … BLP has opened new doors for me, it’s made me more confident. Things like listening and empathy – now instead of getting embarrassed, I think of how other people react to things, and learn how I can react when I don’t know something. I mentioned BLP to my friends at ski school, and then the whole week we were talking about how we had naturally used BLP. We were questioning what we could do better, looking for different techniques to improve our skiing, looking out for dangers. It’s something to structure your life on, you use it every day.

Clara, Year 9

In this chapter we start by looking at some real examples of where the ideas we have been discussing are already being put into practice – where children are being systematically helped to build 21st century character and, at the same time, are getting better results than ever. We hope you’ll see that there are many reasons to be optimistic. We just need to shout about them and use the examples they offer to encourage other schools to do similarly. We want you to feel inspired to go forth and multiply.

Pioneering schools

Miriam Lord Community School is a very large primary school in Bradford. It has high proportions of children for whom English is not their first language, and of those who are eligible for the pupil premium. Many children join the school with skills and knowledge that are well below the national average. In 2013 the inspectors put the school in a category called ‘requires improvement’. In July 2014 they visited again, and now Miriam Lord is ‘good with outstanding features’. Their report says: “The pupils are very keen to learn. They say that teachers ‘make our tasks fun and challenging’, and that ‘the work can be a bit hard, but the hard bits make you learn new things – you don’t learn when you don’t have a challenge’.”1 The school has used the Building Learning Power framework to build this attitude quite deliberately. Here are some examples of what you might see and hear if you were to drop in to Miriam Lord.

The Year 2s are developing what they call their ‘noticing muscles’. They have six questions that are guiding their learning:

1. Am I good at noticing details (e.g. similarities and differences between things)?

2. Do I want to know more about what we are studying?

3. Have I got a good question to ask?

4. How good am I at staying on task?

5. How good am I at concentrating on what I am doing despite distractions?

6. Am I interested in what I am doing?

In a maths lesson, the children are working with blocks of different lengths and colours to represent different numbers (you may know them as Cuisenaire rods). One boy, Arjan, is trying to represent the number 67 – he needs six tens-sticks to represent the 60, and then seven unit-cubes to make the 7. But under the 7 he has put seven tens-sticks. Instead of correcting him straight away, his teacher asks him to ‘notice the details’ of what he has done.

Arjan: I notice that I’ve put six tens-sticks under the 6.

Teacher: What do you notice?

Arjan: [points at the units column where he has put seven tens-sticks instead of seven unit-cubes] That I’ve got this bit wrong.

Teacher: Well, you’ve noticed something useful. What numbers did you make with the equipment?

Arjan: 60 and 70.

Teacher: So, now can you revise your answer?

Arjan changes the units column to correctly show 7 unit-cubes. His teacher asks him to explain what he now notices.

What do you notice about that little exchange? You may have been struck by the fact that Arjan does not get upset about having made a mistake; he just spots it and uses his observation to think how to correct it. He isn’t just being helped to get the right answer (although he does); he is being coached to be more attentive to what he is doing, to think more clearly, to correct his own mistakes and not to get upset just because he didn’t get it right first time. Cumulatively, this ‘coaching’ will make Arjan a better learner: more confident, enthusiastic and perceptive about his learning so he will learn faster and more effectively.

The Year 3s are getting toward the end of a unit focusing on ‘How to live a healthy lifestyle’, and to consolidate their learning they have been asked to plan and run a successful ‘healthy cafe’ to which their families will be invited. They are using a tool called the TASC wheel (Thinking Actively in a Social Context), which was created by Belle Wallace.2 The TASC wheel helps them orchestrate the task; their teacher is doing very little to guide or rescue them from the considerable difficulty of the assignment. Instead pupils respond to a series of helpful prompt questions such as:

● What do I know about this?

● What is the task?

● How many ideas can I think of?

● Which is the best idea?

● How well did I do?

● What have I learned?

The wheel provides a colourful and pupil-friendly way of structuring planning, thinking and progress.

The children set to work researching menu choices, budgeting the cost of various ingredients and designing and writing the invitations. They also design a questionnaire to gauge customer satisfaction with various aspects of their performance. Then they learn how to set the tables, prepare the food and drinks and, when their cafe opens its doors, gather orders from the ‘customers’, serve the different dishes, write out the ‘bills’, give them their change and dish out the questionnaires. After the event, they analyse the results from the questionnaires, and, as a whole class, use the information gleaned to reflect on their performance and to draw lessons for the future.

Bryan Harrison, the head teacher, wrote, “The event was well attended by parents who commented on how professional the event was, and how much confidence the children had shown. There were genuine moments of deep pride shared between the children and their families.”

Nobody could do anything other than applaud this as a wonderful piece of education. The children are being stretched and are rising to a significant challenge. They are undaunted by this because their previous learning has cumulatively built up their capacity to cope and to be independent, resourceful and collaborative. They are using their maths and their English in meaningful ways that deepen their competence. They are learning to plan, reflect, make collective decisions and take responsibility – all habits that will benefit them in later life. They are utterly engaged and, at the end, bursting with pride at what they have managed to achieve. The community is involved and impressed. The parents see the growth in their children, and are totally supportive of the school. The children, let us remind you, are 7 and 8 years old.

Whether it is Blackawton bees or a healthy cafe doesn’t matter. What does matter is that teachers are finding questions and creating challenges that engage children’s interest and energy, and are skilled enough to structure the activities that follow in a way that systematically stretches valuable, transferable habits of mind. At Miriam Lord, the children are learning something really useful – to understand the basics of a healthy diet – and they are using this topic as an exercise-machine to drive the development of other, really useful attitudes and capabilities. What’s not to like?

Further up the school, the Year 5s are studying the Amazon. All kinds of useful and interesting discussions and understandings can flow from this topic, and do: the different beliefs of indigenous peoples, the threat to wildlife, forests as ‘the lungs of the world’, the complex politics and economics of developing countries such as Brazil, and so on. But at Miriam Lord, this topic is also being used to develop more sophisticated learning habits and skills, such as internet research and note-taking. The children are given a text and challenged, both alone and in small groups, to distil out the key points (an ability that had been noted as underdeveloped in these children by an earlier assessment).

Within the topic there are a range of tasks that offer different degrees of challenge, and the children are encouraged to reflect on their own abilities in relation to the tasks, and select the ones that give their ‘learning muscles the best stretch’. This not only gives the children a greater feeling of ownership and engagement, but also develops their ability to assess their current levels of understanding and ability for themselves. In a similar vein, children are encouraged to decide for themselves when to work on their own, when it would be better to join a group of other children and when they really need some help and guidance from the teacher. Over the course of the term, the children made 3D models of key features of the Amazon which the head teacher describes as ‘stunning’. They wrote articles about some of the environmental issues and stretched their mathematical competence by working out rainfall averages and presented these in a variety of formats using ICT.

Any ideologically driven rhetoric about the inadequacies of project work, or the absurdity of ‘expecting children to be experts’, utterly fails to do justice to these sophisticated classrooms, and to the interwoven development of knowledge and understanding, technical skills and habits of mind, which is palpably taking place. There is no opposition between ‘gaining knowledge’ and ‘learning to think’. They form a double helix. Knowledge deepens and broadens at the same time as the capacities to think, learn and be creative are being cultivated.

A few miles west of Bradford, across the Pennine Hills, lies the village of Barrowford, where the primary school has also made extensive use of BLP ideas. The school hit the headlines worldwide in July 2014 because the head teacher, Rachel Tomlinson, sent to every pupil in Year 6 a customised version of a letter that had originated in America. (Teachers – along with scientists and artists and athletes – are always borrowing and adapting each other’s ideas; that’s how good practice spreads.) Here is an extract from Rachel’s letter:

Dear …

Please find enclosed your end of KS2 test results. We are very proud of you as you have demonstrated huge amounts of commitment and tried your very best during this tricky week.

However, we are concerned that these tests do not always assess all of what it is that make each of you special and unique. The people who create these tests and score them do not know each of you – the way your teachers do, the way I hope to, and certainly not the way your families do. They do not know that many of you speak two languages. They do not know that you can play a musical instrument or that you can dance or paint a picture. They do not know that your friends count on you to be there for them or that your laughter can brighten up the dreariest day. They do not know that you can write poetry or songs, play or participate in sports, wonder about the future, or that sometimes you take care of your little brother or sister after school … They do not know that you can be trustworthy, kind or thoughtful, and that you try, every day, to be your very best … The scores you get will tell you something but they will not tell you everything.

So enjoy your results and be very proud of these but remember there are many ways of being smart.

The letter went viral on the internet – because, we must presume, it rang a deep bell with millions of people. The letter praises the children for their achievement on conventional tests (the so-called Key Stage 2 SATs), and told them to be proud of their results and of their willingness to work hard and try their best. But it also reminded them of the other accomplishments and layers of their character that they should be proud of too: trustworthiness, diligence, cheerfulness, kindness, artistic flair.

There is nothing in the letter that could possibly be read as encouraging the children to devalue their education. However, Chris McGovern, chairman of the Campaign for Real Education, was quoted in the Daily Mail on 15 July as saying: “They’re undermining confidence that the children may have in the education system. … It’s an indirect attack on the Government. The message that the school is sending to the children is that somehow they are being betrayed by the system. … Schools should not be a platform for promoting political ideologies – they should be neutral.”3 Hmm, you have to work quite hard to see it that way. And you have to be rather uninquisitive, at the very least, to see why such dangerously seditious and anarchic extremism should appeal so strongly to millions of regular mums and dads.

Perhaps what is objectionable is not the temerity of mentioning the 95% of children’s characters, accomplishments and interests that are ignored by much conventional education, but the very neglect of those qualities by so many schools. By the way, both the achievement of pupils and the quality of teaching at Barrowford was ‘good’ at the last Ofsted inspection, and the inspectors were moved to comment approvingly:

Spiritual, moral, social and cultural awareness is a strength of the school. The curriculum continuously reinforces positive attitudes towards learning and the development of skills and qualities such as perseverance, reasoning and empathy.4

How many times do we need to be told that the systematic development of positive learning dispositions is perfectly possible, and perfectly compatible with a commitment to literacy, numeracy and good test scores?

Being resilient has helped me try things; like, if I don’t know a question in SATs I’ll now have a go – and I might get it right! Also, if I don’t have a pen or pencil or something, instead of sitting around waiting for one I’ll go to the back of the classroom and get one! To start with I didn’t like being asked to be reflective; I didn’t see the point. But now I understand that it’s better to find your own mistakes, because then you’ll never do it again. And being reflective has helped me write better stories with more detail that have all the good things in!

Hugo, Year 6

In Year 5 I wasn’t very resourceful. I would come in in the morning and wait to be told what to do. Now I come in and get on with the task that is set. And BLP has taught me to check my work through and learn from my mistakes. When I play games I am not a sore loser any more; I just think about what I need to do to win next time. Overall I think BLP has had a massive effect on me.

Jake, Year 6

Before BLP I was never able to finish what I had started. Now I can finish my work, I pay attention more and I am not distracted any more. I notice more things – connections etc. – during the lesson. And before, I never asked questions and I never dreamed of trying to look for links between the topic and what I already knew. But now I ask more questions, get my resources sorted and basically don’t fuss!

Elsie, Year 6

Let’s stay in the north of England and travel back over the Pennines to North Shore Academy in Stockton-on-Tees. North Shore is a challenging secondary school. In January 2012 it was placed in Ofsted’s lowest category, ‘special measures’. The GCSE results that year were dire – just 22% of pupils achieved five good GCSEs including English and maths. A new principal, Bill Jordan, was brought in to turn things around – and he decided to continue with the work that his deputy, Lynn James, had already started to champion to build students’ ownership of learning. They predicted, a year later, a GCSE success rate of 47%. In fact, 53% of students in 2013 hit that GCSE target. In the same year, three other local secondary schools, none with as tough a catchment area as North Shore, achieved 33%, 35% and 47%. This is an astonishing turnaround.

What is Bill and Lynn’s philosophy? They have posted a list of the ‘commitments’ which North Shore now makes to all its students on their website. Here are two of them:

● Outstanding learning and teaching which engages pupils and is active, collaborative and encourages independence.

● Student voice intended to empower and involve young people in the development and delivery of their own education and the life of their academy.5

As school leaders, they have aimed to establish a culture of good behaviour, and then asked the teachers to develop their teaching so as to give the students progressively more independence and responsibility for their learning. To pull this off takes time and support, of course, and Lynn has asked BLP principal consultant Graham Powell to work with staff on a regular basis to help them shift their practice. To begin with, some of the teaching was spoon-feeding the students too much, and they had become used to adopting a rather passive role in the classroom. In his early observations, Graham noted:

Students are compliant and attempt tasks set but their engagement is limited and teachers are the focus of attention for too long before setting them to work on their own. In too many lessons students comply but aren’t encouraged to enjoy the struggle of learning which assures progress and engagement. Students are not always required to think sufficiently for themselves. Teachers do too much of the thinking for them. Teachers might make more use of activities that require students to ask questions of themselves, each other and the resources that are before them.

Over time, teachers have changed their ways, and now students have become more active in managing, researching, designing and evaluating learning for themselves and – though we are sure you don’t need reminding – their results are rocketing up as well. In their latest Ofsted inspection, North Shore got a ‘good’ for teaching and learning. The report noted: “Since the last full inspection, the overall quality of teaching has improved significantly” and “Students … have good attitudes to learning.”6

In various situations outside of school BLP has helped my thinking to be more logical and analytical. If I get lost I now think through all the possibilities of who to contact, how to contact them, where to go, why I would go to that place and how that would help me.

Within school it helps you to persevere when you just want to give up! Recently, I had to produce an exact replica of a Picasso painting for DT homework. It took a very long time. I had to keep at it, until I got everything right – the proportion, the tone. BLP helped me with that, both consciously and subconsciously. When I finished it I felt really proud! And I set my standards really high!Dominic, Year 8

Next, we come south to another comprehensive school, Goffs School, an academy in the stereotypically leafy Home Counties. Although the levels of achievement, and the nature of the students, are very different from North Shore, the journey that the teaching staff have been on over the last two or three years has been surprisingly similar. Nigel Appleyard, a history teacher who has been spearheading the development of BLP at Goffs, describes his own experience with his sixth-form class:

I started to provide them with stimulus material that would get them stuck. I wanted them to generate their own questions and explore possibilities for themselves. I was determined to make them do the thinking! At first I met with some resistance. One student in particular intimated that it was my job to teach the group and give them the answers that they could repeat in the exam to get the grades they needed. I explained to them that that way of teaching wasn’t going to prepare them properly for the demands of the exam, or for their future needs.

I sensed that some of the group were not convinced. I didn’t give in, and gradually they came to expect to be challenged in lessons and to rise to it. They started to get disappointed if I didn’t set them something intriguing or problematic. Things have moved on, and they are much more actively engaged and now regularly involved in the planning and delivery of lessons. They have taken on responsibility for creating provocative, relevant and stimulating starter activities to ‘warm up their learning muscles’ and they lead the discussions that distil what they have learned and what they need to learn. They have become a different group: they have transformed themselves into students who no longer depend on me to provide them with all the answers.

And the exam results are improving year on year. In 2014, there was a 99% pass rate at A level, and the school’s own target for A and A* grades at A level was exceeded by 11%!

At the school I’m in now, the economics teacher had walked out – so these kids were scheduled to have economics lessons, but without any teacher. I kind of adopted this class. I held back one guy at the end of the lesson and gave him a book to read. I put it in his hands, so that everyone could see. The next day, another student who’s usually really nice was giving me a little bit of attitude. At the end of the lesson, everyone left but she kind of hopped around, and finally said, “I want a book too.” And this is what I was going for to begin with. I, of course, had the exact book I wanted to give her. Over the next week, every one of my kids came in and asked for a book to read. So here are kids who are probably not going to pass the exam – most of my students have known their predicted grades of E and D for so long that they have no aspiration to go to uni – who are intellectually curious enough to want to be challenged.

Rob, economics teacher, London secondary school

Our final example is Honywood Community Science School in Coggeshall, Essex. Its head teacher is a passionate advocate of using digital technology to give students more responsibility. They are encouraged, following clearly laid out schemes of work in maths, to plan their own learning pathways, and are coached in how to do this by higher level teaching assistants. There is also a library of high quality online resources. Honywood is a BYOD (bring your own device) school and students are expected to be able to switch between the online learning which they are leading and more traditional teacher-led instruction. Honywood does not follow any one approach to learning but has built its own well-thought-through approach called HonySkills.

HonySkills at Honywood

● Communicate in writing, orally, physically, graphically and by using ICT.

● Solve problems.

● Cooperate and collaborate with others.

● Analyse information and draw conclusions from it.

● Synthesise information, evaluate and form judgements about it.

● Be creative.

● Gain the knowledge and skills to be healthy in body and mind.

● Persist when times are hard.

● Acquire the knowledge that valuing the struggle to learn will make you more successful.

● Think for yourself.

● Learn independently.

● Be competitive, never being content that you have done your best.

● Conceive of things in abstract as well as concrete form.

● Criticise constructively.

● Take responsibility for your learning and your life.

Head teacher Simon Mason is a driving force and a prolific communicator with his staff. Here is part of what he wrote as a guest blogger on the Expansive Education Network website.7 (There’s more on expansive education on page 135.)

As part of a new curriculum we introduced in September 2011, we have focused on sixteen skills, attitudes, dispositions and behaviours which we feel are essential for people to master if they are to be happy and successful in their lives. Our teachers design learning in two ways; they don’t just think about subject content; they also design learning opportunities that encourage mastery of these skills, attitudes, dispositions and behaviours. Central to our pedagogy is the notion of choice. Currently youngsters are given choices about how they learn, where they learn and how they present their learning. As we develop, we will be offering choices about what youngsters learn and about the length of time they spend on their learning. By offering authentic choice, we have opened up the possibilities for collaboration in learning. We have become used to seeing youngsters learning in self-directed teams, with learning spilling out into our corridors and stairwells as youngsters take ownership and show real responsibility for their learning.

Honywood’s approach to engaging parents is similarly thoughtful:

All research and advice tells us that there is no right way in which to parent. Each of us has a different family background and a unique set of personal circumstances which shape our parenting. Each child is also different: what will ‘work’ for one child may not ‘work’ for another.

A problem shared is a problem halved and having someone to talk to can prove invaluable.

We aim to establish an atmosphere in which situations and problems can be discussed in a confidential and supportive way, hopefully empowering you to be able to return home to your own individual situation armed with ideas and the knowledge that there are people out there, particularly the Family Learning Team and the Cohort Leaders at Honywood, who can support you.

We are happy to help you with a range of problems including:

● Supporting your child through friendship challenges.

● Communicating with my adolescent.

● My adolescent can’t cope with exam stress, is there any help?

● Bereavement and loss.

● Internet safety.

● Who you can turn to when things get tough.

You’ll remember that the CBI called for closer cooperation between schools and families, as one of their headline recommendations. Here it is in vibrant, successful action.

Scaling up

Each of these very different schools has in some real way demonstrated that it is possible to offer educational experiences that systematically develop confident and agile minds – and get great results. But a smattering of schools, you might argue, can hardly change the world. In addition to these living examples of the way forward we need ways of disseminating and scaling up what they are doing. And there are indeed tried and tested ways in which such good ideas can and do get magnified and broadcast. Here are a few.

One of the simplest is called a school cluster. Clusters were originally developed in the middle of the 20th century as a means of sharing resources across schools, especially in rural areas. Schools could share expensive resources – a swimming pool, a theatre or a specialist facility. But these days it’s increasingly how schools are organising their own professional development too. (Maybe your school is part of a cluster, sometimes also called an academy chain.)

Under the Blair government, clusters of schools were actively encouraged by the National College8 as a means of spreading ideas which might improve schools, and it is clear that they did have some success.9 Most recently, borrowing the idea of the teaching hospital from the NHS, successful schools were invited to become ‘teaching schools’ with the responsibility of gathering clusters of schools around them to share good practice. Specifically they were given the opportunity to organise initial teacher training and organise professional development for teachers. By November 2013, there were 357 teaching schools and 301 teaching school alliances in England. The idea of such alliances is to encourage locally led self-improvement. Sounds like a good idea.

But if we tell you that a school can only be a teaching school if it is graded ‘outstanding’ by Ofsted, then you can immediately see a problem. For if the main criterion for admission is Ofsted’s judgement, then the kinds of activities which such alliances promote may well be skewed towards the kinds of activities which are approved of by Ofsted, but not the kinds which we have seen at Miriam Lord or North Shore. We know hundreds of schools which would make excellent teaching schools that would be graded merely ‘good’ by Ofsted. Their ethos might well be more conducive to real-world learning than those which happened to have got the ‘outstanding’ mark.

In some cases teaching schools have set out their stall with an agenda that is closer to ours than to Ofsted’s. An example of this is St Ambrose Barlow Roman Catholic High School in Salford. Again there is a passionate and well-informed head teacher at work, Marie Garside. Over several years Marie has adopted her version of what she calls the creative curriculum – ‘developing in all students the creativity to be able to thrive throughout their lifetimes’. Recently the teaching alliance she leads has become a hub for expansive education in the north-west. Marie and her cluster of schools have chosen to focus on teacher research. She believes that student outcomes are likely to improve if schools can engage with deep questions about the subjects they teach. The alliance is linked to the two universities in Manchester, which help them to explore science and engineering, as well as research methods, and also has long-standing relationships with cultural organisations such as galleries and museums across the region.

But the reason we mention them here is that we know that clusters of schools working together are great ways of growing and nurturing more innovation. We just need to ensure that the goal of any imaginary ‘Mod School Alliance’ is to create more opportunities of the kind that we have been describing in this book, and not merely to improve test scores in a range of academic subjects.

In a small way we have been involved in developing an extended cluster of like-minded schools under the banner of the Expansive Education Network. The hundreds of schools and thousands of teachers, many from overseas, that are part of this group explicitly choose to associate themselves with three of the core beliefs which have run throughout this book. First, they seek to expand the goals of education beyond traditional success criteria to include the kinds of habits of mind we talked about earlier. Second, they want to expand young people’s capacity to deal with a lifetime of tricky things. Third, they want to expand their compass beyond the school gates. Expansive education assumes that rich learning challenges and opportunities abound in young people’s out-of-school lives of music, sport, community and family activities.

At this point you may be wondering whatever happened to local educational authorities. Weren’t they meant to be doing this kind of thing – supporting groups of local schools to get better? Indeed they were. But, sadly, too many of them became casualties of political warfare, were drained of financial support and shrivelled up, died out completely or became privatised. And some, truth to tell, weren’t very good. But a few remain and are thriving. One is the East London borough of Thurrock, which is small enough to gather all of its head teachers together in a large room to really think things through and large enough to have some capability to support schools to develop. Thurrock is flying a flag for expansive education, with all of its schools being encouraged to experiment with new and innovative ways of teaching children, and all the while engaging teachers in evaluating this. (We know, by the way, from the work of researchers such as Professor John Hattie that when teachers become learners again their teaching improves, as does the achievement of their pupils.) Thurrock has decided that it can create a climate in which children can be taught to be creative and resilient at the same time as improving test results. To make sure that teachers and parents understand what they are up to, they have launched an annual awards ceremony to make this point.

The London Challenge is perhaps the best-known example of how clusters of schools can join forces to change the way they do things. Led by Sir Tim Brighouse, a highly experienced and inspirational local authority leader, it was conceived with a strong moral purpose: that every young person in London should receive a good or better education than they were receiving then (in 2003). The London Challenge had a powerful focus on leadership, teaching and learning, and pioneered the use of data (information about every aspect of children’s learning and achievements) for the sole purpose of improvement not punishment. The idea of a clear challenge, coupled with a well-defined programme of action, will be apparent as we go through this chapter, and it is one that we return to in the last chapter of the book, as we believe it can be adapted for our purposes as a call to action.

Employers

If the necessary changes are going to happen, though, there is a strong need for support – and pressure – from outside the education system as well as within it. We mentioned the main employers’ organisation, the CBI, and their publication, First Steps: A New Approach For Our Schools, in Chapter 1. As well as saying the kinds of things which we might expect an employers’ organisation to say – for instance, bemoaning the low levels of literacy and numeracy of English school-leavers compared with many other countries – First Steps laid out a different set of demands, prefaced by this powerful statement:

Change is possible – but we must be clearer about what we ask schools to develop in students and for what purpose.

You could imagine, just for a moment, that employers had been secretly studying the kinds of books and papers we have been reading (and writing) over the last two decades. But they may perfectly well have come to the same conclusions by themselves. Here are three of the things they called for:

1. The development of a clear, widely owned and stable statement of the outcomes that all schools are asked to deliver. This should go beyond the merely academic, into the behaviours and attitudes schools should foster in everything they do. It should be the basis on which we judge all new policy ideas, schools and the structures that society sets up to monitor them.

2. The adoption by schools of a strategy for fostering parental engagement and wider community involvement, including links with business.

3. The Department for Education should accelerate its programme of decentralisation of control for all schools in England. This should be extended to schools in other parts of the UK, freeing head teachers to deliver real improvements.

First Steps is really a manifesto for a radical change to the way we currently organise schooling. Its central demands chime strongly with our own long-held views. The first of their suggestions – that we should go beyond the subjects on the curriculum to think more profoundly about what it is we think the outcomes of schooling should be – aligns most strongly with the agenda we have laid out. Their second recommendation – that we should empower parents to engage with schools – is the focus of the next chapter.

In our research for this book we have spoken with hundreds of parents, students, teachers and head teachers. In the course of our conversations, we were struck by the letter below as an example of exactly the kind of thing the CBI is calling for.

Letter from a parent to her child’s primary head teacher

Dear Head Teacher,

I want to write and thank you for recently running the parent workshops on how to support our children in ‘Building Learning Power’. Your talk has given me a vocabulary to use when talking to my children to help convey some truly important values that I have always believed to be vital to both success and happiness. Specifically that ‘effort is more important than ability’ and ‘mistakes are part of the learning process/to succeed you have to be prepared to take the risk of failing’. I loved the analogy you used of the brain being a muscle that has to be exercised and made fit for learning. I have been talking a lot about overcoming adversity with my children.

As you know, we are lucky enough to have a talented child in your school, but her aversion to challenges and her sometimes rather thin skin regarding mistakes have worried us. However, after the workshops we now feel more resourceful in dealing with her reticence and we have the start of a language that we can use to help her. We have seen an immediate impact on her from the school’s initiative to build a positive attitude to learning; we have seen our daughter fight back her immediate inclination to want to give up on things when they become tricky and we have praised her for it.

We realise it is still early days and we will have to work hard not to fall back into old bad habits of rescuing and reassuring her! Well done though; you have opened the debate, set us a challenge and given us some very useful tools, ideas and initiatives to go forward with as a family. Thank you for a very important beginning.

All the best,

Teresa, Year 4 mum

At the end of 2014 the CBI published an ‘end of year report’ on their First Steps agenda. On every aspect they rated the government poorly using marks that ranged between B- to D! The D went for the first of their suggestions, that we develop a clear statement of the outcomes that all schools should deliver:

The eco-system of a school should foster academic success, but also go beyond it to the development of the behaviours and attitudes that really set young people up for adult life.10

In language which even more strongly echoes our own, they go on to specify these behaviours and attitudes:

| Characteristics, values and habits that last a lifetime | |

| The system should encourage people to be | This means helping to instil the following attributes |

| Determined | Grit, resilience, tenacity |

| Self-control | |

| Curiosity | |

| Optimistic | Enthusiasm and zest |

| Gratitude | |

| Confidence and ambition | |

| Creativity | |

| Emotionally intelligent | Humility |

| Respect and good manners | |

| Sensitivity to global concerns | |

The message is obvious. Many employers have a clear vision of what the desired outcomes of school should be for young people, but so far the government is not listening. Hence the D grade awarded to the Department for Education. But the pressure will mount. Employers in the UK are a powerful group, not to be idly dismissed by governments. They are helping to create a climate in which our balanced approach can and will flourish.

Professional bodies

Two teacher bodies are currently asking and answering the kinds of questions which we have been posing. In the UK, the Association of School and College Leaders and its ‘Great Education Debate’ have stimulated useful thinking. The debate takes as its starting point this statement:

We believe that it is time for everyone with a stake in education to have a say about the future of our schools and colleges policy – employers, parents, young people, academics, politicians, teachers, school and college leaders. We want to create a vision and a plan that everyone can sign up to.11

The Great Education Debate recently published a summary of its conclusions.12 These centre on the idea of a school-led, self-improving system. Now, this may sound like jargon to some readers, but read on a little more in this document and you will find many recommendations that mirror those we have been suggesting. Here is a flavour, some echoing the CBI suggestions we have been exploring:

In an ideal world we would debate these issues and reach a shared view on the purpose of education. We would determine the relative weight to be accorded to the differing drivers. That would then inform the framing and the content of the curriculum … This is not as farfetched as it sounds: other countries such as Singapore do precisely this.

We need to facilitate systematically the professional development and lifelong learning of existing teachers.

Any definition of the purpose of education would surely include maximising the life chances of all young people by making them work-ready, life-ready and ready for further learning.

The unique challenges of the world in the 21st century require a better understanding of the underpinning personal capacities that are the difference between the success and failure of otherwise identical young people.13

The last of these opinions speaks poignantly to the comments of many of the young people we have quoted in the book.

A second initiative called ‘Redesigning Schooling’ has been stimulated by a professional body called The Schools Network.14 At the heart of Redesigning Schooling is a plea for the teaching profession, especially school principals, to take charge of the debate about the future of education. They say:

These are tough times for school leaders but we know as a profession we have to change. Surely we have to have the courage of our convictions and put in place those opportunities that we feel equip our students most appropriately for life in the digital age and for taking their place in the global workspace?

Do we always have to follow the Government line, or can we as a profession take more control of the future of education and the steering of our young people towards global citizenship? Redesigning Schooling is a campaign lead by SSAT and its member schools, leading thinkers and academics to shape the teaching profession’s own vision for schooling.15

Precisely because it is seeking to develop debate and innovation within the teaching profession itself, Redesigning Schooling is necessarily taking time to build its point of view. But, through its events and publications, it is encouraging school leaders to articulate with greater confidence their own vision of education. In the next chapter we will look at ways in which we can all accelerate the changes we want to see.

We’ve also referred to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (see Chapter 2). The OECD is the organisation which runs the Programme for International Student Assessment, home of the infamous PISA tests which all education ministries are keen to do so well on. (How educators love their acronyms!) The man who runs PISA is a German statistician called Andreas Schleicher. Many countries (including the UK) have become so mesmerised by the international league tables to which the PISA data gives rise that they can think of nothing more inspiring, as a goal for education, than to beat Finland or Shanghai in these tables. Many have argued that the very existence of these tables has driven education systems around the world in a regressive direction. Some countries – Wales is cited as being one – have even started to tailor their education systems specifically to improve their PISA rankings.16 It’s not that it’s a bad idea for countries to know how they are doing in teaching maths, English and science; it’s just that, if these paper and pencil tests are given undue weight, they start to eclipse other good educational goals – like the habits of mind – that can’t be so easily measured.

Schleicher himself is all too aware of this danger. In fact, his own model of education is a well-balanced one (see the figure opposite). It is easy to see how the things we have been arguing for in Chapters 1–4 can be fitted into his four rectangles. He is trying to broaden out the PISA tests so they do actually assess things like students’ capacity for collaborative problem-solving or creativity. This is not easy to do, but the OECD is leading the research in this area.17

Dimensions and challenges for a 21st century curriculum

| Knowledge Balance conceptual and practical and connect the content to real-world relevance |

Skills Developing higher-order skills such as the 4Cs: creativity, critical thinking, communication, collaboration |

| Character Nurturing behaviours and values for a changing and challenging world: adaptability, persistence, resilience and moral-related traits (integrity, justice, empathy) |

Meta-layer Learning how to learn, interdisciplinary, systems thinking |

Source: Andreas Schleicher (ed.), Preparing Teachers and Developing School Leaders for the 21st Century: Lessons from around the World (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2012).

Two examination boards have also been actively seeking to broaden what it is that schools do; they are City & Guilds and Pearson. City & Guilds have been promoting research into the practical learning and apprenticeships which so many young people want, in order to help schools and colleges provide more effectively for the many students who do not choose an academic route. As contributors to this research, we have been vocal in suggesting that, as with schools more generally, we need to think about what else, other than routine skills, young people should be learning. In particular, we have suggested that they need to learn to be resourceful (able to deal with the non-routine), to develop pride in their work (thinking like a craftsman, never accepting the slapdash and always striving to do their very best) and build a set of wider skills beyond the particular vocational pathway on which they are embarked.18

Pearson has contributed to the debate by commissioning research into young people’s views of school.19 The central conclusion of this study was that it was “difficult for them to understand the relevance of school learning to their future work aims”.

There appeared to be three causes of this disconnection:

1. Little association between lesson content and career preferences.

2. Teachers not knowing their pupils’ hopes and dreams.

3. Inadequate opportunities to gain foundation ‘life skills’.

Students also express the need for learning that relates to their goals. They are hungry for that connection, and speak easily and specifically about what they want to do with their lives.

Here are some of the points the student interviewees made:

Once we leave school we’ll need to be much more independent, so we should learn things that will help us later on.

Teachers shouldn’t just be at the front – they should interact in the classroom.

Schools need to let us know more about the future, jobs and help us to know more about careers, relating learning and work …

I have never been asked about my hopes and dreams.

Teachers could make their classes more relevant to my future goals by asking what I wanted to do in the future and help me try to achieve those targets by helping me in the areas I need help in.

Whatever these students’ schools, backgrounds and ambitions, their voice is not one of hostile disaffection. They are thoughtful and articulate, and the points they make are important and thought-provoking. If the groundswell for change is to gather momentum, students themselves will be powerful participants in the process.

The third sector

Finally in this chapter we shouldn’t forget the role that is being played by charitable bodies. Of course, some of them are quite capable of campaigning for versions of education which are narrow and backwards-looking. But most are motivated by big moral ideas – social justice, increased well-being, cohesion, better care of our planet and lifelong learning. Some undertake research. Others produce resources. Some are funding bodies. Others lobby for the changes they desire. Although it is somewhat invidious to mention just a few examples, nevertheless we are going to do just that!

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (or the RSA as it is more widely known) has a long history of educational innovation. In 1980 it published a manifesto called Education for Capability which made many of the same points we are highlighting in this book.20 More than a decade ago, the RSA suggested that we could organise what teachers teach not into subjects but into ‘themes’ and ‘competencies’. They called it Opening Minds.21 Some 200 schools have now adopted its principles.

When Opening Minds was first introduced most schools organised what they taught according to subjects. So your child might have a lesson of English, then one of geography or science and so on. Look at a typical secondary school timetable and, odds-on, it will still be organised in this way, with five or six different subjects in roughly hour-long blocks each day. The RSA turned this on its head and asked a different question. What would school look like if we organised it in terms of the competences we wanted students to develop rather than by subject area? They came up with five such competences: citizenship, learning, managing information, relating to people and managing situations. These kinds of things are much closer to what we called utilities in Chapter 4. Here’s an example of what they thought might go into managing situations:

● Time management – students understand the importance of managing their own time, and develop preferred techniques for doing so.

● Coping with change – students understand what is meant by managing change, and develop a range of techniques for use in varying situations.

● Feelings and reactions – students understand the importance of both celebrating success and managing disappointment, and ways of handling these.

● Creative thinking – students understand what is meant by being entrepreneurial and initiative-taking, and how to develop their capacities in these areas.

● Risk-taking – students understand how to manage risk and uncertainty, including the wide range of contexts in which these will be encountered and techniques for managing them.

You could theoretically just replace subjects with competences and end up designing a curriculum of one-hour blocks looking at time management or risk-taking. But such an approach would clearly be (a) silly and (b) entirely against the spirit of what Opening Minds is proposing. These competences need to be developed through rigorous projects and enquiries of the kind that we were suggesting would feature in a Key Stage 3 curriculum.

Think of one of your pupils (if you are a teacher) or your children (if you are a parent) and the situations they encounter, or think about yourself and the kinds of things you need to manage in your own life. Whether it’s the weekly shop, homework, getting ready for a holiday or football practice, we all need to be able to manage time. Similarly, in a fast-moving world, we all need to be able to deal with change. Do we embrace it? Do we get grumpy and resist it? Do we ask for help? Do we find out more? Do we think of different ways in which we could react and select the most appropriate one? We think it is clear that these examples of managing situations are manifestly things that help life go more smoothly and effectively and, therefore, qualities you’d want the next generation to have.

This highlighting of useful habits of mind, and weaving them more systematically into lessons, is no great revolution. Both New Zealand and Australia, for example, have chosen to organise their schools by foregrounding the capabilities they want students to acquire in the course of studying important things. You cannot teach competences in isolation; they have to have content too. Opening Minds schools tend to assume that the organisation of the school day may, in part at least, be about creating chunks of time where pupils can work with teachers, employers and others on rigorous, challenging enquiries or projects. By doing this, pupils learn ‘how to’ at the same time as they think about the whys and whats of any discipline.

Here’s one more example of a charitable body creating optimism on the ground. The Sutton Trust describes itself as a ‘do tank’ (as opposed to a ‘think tank’). We think it has a place in this chapter because of its close links to the real world of schools. It is trying explicitly to use research to change policy and practice. Above all, the Sutton Trust is trying to help children who are less well-off do better at school and then in life – what’s often referred to as improving social mobility.

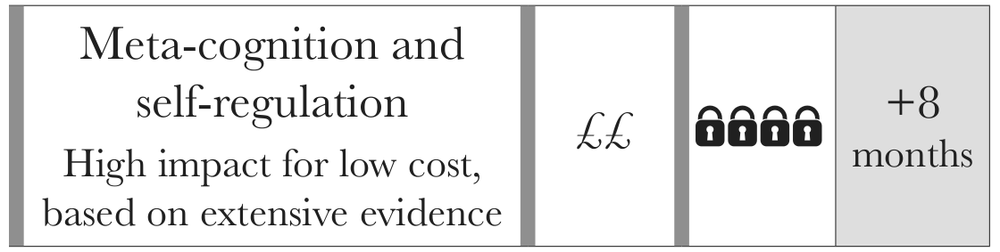

A practical example of what they produce, in collaboration with the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), is the Teaching and Learning Toolkit for teachers.22 The toolkit takes a number of different teaching methods and then distils the research on its effectiveness into a really clear ‘dashboard’ that signals its degree of impact, cost to implement, the strength of the evidence in its favour (the icon that looks like a weight or possibly a fashionable handbag!) and then gives it an overall score in terms of the number of months by which it might accelerate pupils’ progress. Not all the teaching methods they have evaluated are directed at building up students’ habits of mind – some are only assessed in terms of their effect on traditional examination grades – but some of them are.

For example, the screen grab above shows the dashboard for teaching strategies that develop metacognition and self-regulation – two of the most powerful habits of mind we have been focusing on. Strategies for building metacognition involve getting the students to think more explicitly about their own learning. For example, they are asked to set goals, anticipate how much time a task will take, evaluate their own work or step back and check the way they have been working or discussing to see if they can improve their modus operandi. (We looked at some of the strategies for building self-regulation in Chapter 3.) For example, they might include learning how to manage distractions or how to use motivational self-talk in the way that athletes and sportspeople regularly do. The evidence for the effectiveness of these strategies is strong, especially (but not entirely) with children who have been making slower progress. Overall, adopting these kinds of strategies in the classroom accelerates students’ progress by as much as eight months. And the costs are relatively low, mainly relating to professional development that shows teachers how these strategies are best implemented. If teachers can help students to get better test scores, and at the same time give them mental habits that are useful in all kinds of real-life situations, how could anyone possibly object?

To sum up: the future of schools, as we suggested at the start of this chapter, is already here, even if it is not yet equally available to all of our children. In the next chapter we offer a few suggestions of things that can be done by parents at home and then, in the final chapter, invite you to consider taking action on a broader stage.

1 Ofsted, Inspection Report: Miriam Lord Community Primary School (15–16 July 2014).

2 For a clear explanation of where TASC came from, see Belle Wallace, Teaching thinking and problem skills, Educating Able Children (Autumn 2000): 20–24. Available at: http://teachertools.londongt.org/en-GB/resources/Thinking_skills_b_wallace.pdf.

3 Sarah Harris, There are many ways of being smart … Headteacher writes to pupils saying not to worry about exams, Daily Mail (15 July 2014). Available at: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2693045/Primary-school-headteachers-inspirational-letter-pupils-ahead-test-results-earns-praise-parents.html.

4 Ofsted, Inspection Report: Barrowford School (11–12 September 2012).

5 See www.northshoreacademy.org.uk/about/vision-values.

6 Ofsted, Inspection Report: North Shore Academy (12–13 December 2013).

7 We have created an alliance, the Expansive Education Network (www.expansiveeducation.net), and we have written a book telling the stories of schools across the world who are expansive educators: Bill Lucas, Guy Claxton and Ellen Spencer, Expansive Education: Teaching Learners for the Real World (Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research, 2013).

8 This body has been renamed twice in its short life in ways that clearly point to prevailing political opinions. First it was the National College for School Leadership, then the National College for Leadership of Schools and Children’s Services. It became the National College for Teaching and Leadership in 2013.

9 See Alison Lock, Clustering Together to Advance School Improvement: Working Together in Peer Support with an External Colleague (Nottingham: National College for Leadership of Schools and Children’s Services, 2000).

10 CBI, First Steps: A New Approach For Our Schools. End of Year Report (London: CBI, 2013). Available at: http://www.cbi.org.uk/media/2473815/

First_steps_end_of_year_report.pdf.

11 See www.greateducationdebate.org.uk/.

12 ASCL, Leading for the Future: A Summation of the Great Education Debate (London: ASCL, 2014). Available at: http://view.vcab.com/?vcabid=geaSeneagSclphnln.

13 ASCL, Leading for the Future.

14 We have contributed two pamphlets to the Redesigning Schooling campaign: Guy Claxton and Bill Lucas, What Kind of Teaching for What Kind of Learning? (London, SSAT, 2013). Available at: http://www.ssatuk.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Claxton-and-Lucas-What-kind-of-teaching-chapter-1.pdf; and Bill Lucas, Engaging Parents: Why and How (London, SSAT, 2013). Available at: http://www.ssatuk.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/RS6-Engaging-parents-why-and-how-chapter-one.pdf.

15 See http://www.redesigningschooling.org.uk/campaign/campaign-hopes/.

16 See William Stewart, How PISA came to rule the world, TES (6 December 2013). Available at: http://www.tes.co.uk/article.aspx?storycode=6379225.

17 See, for example, OECD, PISA 2015: Draft Collaborative Problem Solving Framework (March 2013). Available at: http://www.oecd.org/callsfortenders/Annex%20ID_PISA%202015%20Collaborative%

20Problem%20Solving%20Framework%20.pdf.

18 See Bill Lucas, Ellen Spencer and Guy Claxton, How to Teach Vocational Education: A Theory of Vocational Pedagogy (London: City & Guilds Centre for Skills Development, 2012). Available at: http://www.skillsdevelopment.org/PDF/How-to-teach-vocational-education.pdf.

19 See http://uk.pearson.com/myeducation/my-education-report.html.

20 RSA, Education for Capability Manifesto (London: RSA, 1980).

21 See www.rsaopeningminds.org.uk/.

22 See www.suttontrust.com/about-us/education-endowment-foundation/teaching-learning-toolkit/.