If you have completed reading Part One you will now have a robust understanding of why people keep secrets. This part will provide you with some essential knowledge on how to unlock those secrets, before moving on to the practical aspects of accessing hidden information in Parts Three and Four.

The adage ‘knowledge is power’ is usually true, but power is usually reduced when the information is widely shared. Secret knowledge, however, remains powerful and can provide a significant advantage for the secret-keeper. Conversely, the power of such knowledge may be destructive for the secret-keeper, as is the case with some family secrets (discussed in Part One) or in the case of a child keeping secrets about being abused or bullied. In these latter cases, sharing the secret information (with a parent, teacher or counsellor) will reduce the powerful impact and dilute the negative influence of the secret information.

As a parent, teacher or counsellor, being able to access the harmful secrets of a troubled child can provide a greater level of understanding and allow better support for the child. In business, it can be a major advantage to know the hidden information of other companies, competitors and even colleagues. For senior managers, HR executives and workplace interviewers, being able to access hidden information can provide an insight into the real situation, add significant value to decision-making and aid improved workplace management.

For police and other law enforcement professionals, being able to have a person of interest volunteer information in the absence of coercion of any sort can greatly enhance the accuracy and efficacy of an investigation and also the reliability and quality of evidence. In our personal lives, some associates, friends and even our intimate partners may keep information hidden that you may need to know to better protect yourself or to better know and understand that person.

In all these cases, it is an advantage to know what is being hidden from us. Being the target of someone’s secrecy can place you at a disadvantage or leave you vulnerable. Despite this, on occasion others aim to keep information to themselves or to share it with some—but not you. Fortunately, there are some scientific aspects of secret-keeping and some clever interpersonal techniques that we can utilize to uncover that hidden information; the process is called elicitation.

What is Elicitation?

‘Elicitation’ is both a term and a tactic used extensively by government intelligence agencies, covert operatives and undercover agents to describe the subtle verbal extraction of information from persons of interest. Put simply, elicitation is a conversation with a learning agenda. Secret agents and spies who use skilful elicitation techniques are able to learn a great deal from the person of interest who, if questioned directly, would refuse to provide that information.

Some may think that type of activity only occurs in the world of espionage and has no relevance to our daily lives. I don’t believe that is the case; we are the victims of elicitation every day. Individuals and companies are attempting to extract information from us constantly. Perhaps I’m being thoroughly paranoid? I don’t think so …

Pause and ask yourself if you have ever registered on an internet site by providing some of your information so you may comment, blog, receive special deals or vouchers, make purchases, join the discussion forum or gain access to the subscriber’s area. Have you ever filled out a quick questionnaire that offers the chance of a prize, or left your business card in a bowl on the counter of a shop that offers a monthly prize to one business card holder? Innocent and non-threatening enough, but our information is being elicited from us, even if we mask our real identity.

Consider how many ‘rewards cards’ you may have and the number of ‘customer loyalty programs you participate in. For example, cards used when travelling (frequent flyers and electronic public transportation cards), places you stay (hotel rewards programs), making purchases using both your ‘earn points’ and credit cards, and loyalty cards for fuel, food, groceries, coffee, clothing, etc. These all gain you points, gifts or discounts, but they are also a very effective way for companies to ‘elicit’ information from you, ranging from your personal details (when you first join) to your purchasing, eating, travel and banking habits and preferences. Even the type of reward you select or how you spend your reward/gift provides vital marketing information for the collecting company. Our participation and use of reward cards and customer loyalty programs have been so normalized in our lives that we simply accept it as a part of 21st century living and we unsuspectingly provide constantly updated information to others who use it for their commercial benefit.

If these companies wrote to us and asked us to provide all our purchasing and travel information and to keep them updated periodically—in the absence of a financial reward or gift—most of us would simply refuse to share such an array of information. However, we happily participate by using these cards and we are not alone. This type of ‘elicitation line’ successfully works on millions of people around the world by promising a benefit and very subtly disguising that a vast amount of our personal information is being electronically taken from us—this is corporate elicitation, and it works.

These programs use the ‘elicitation line’ of financial incentive or advantage and it works on most people. (‘Elicitation lines’ are discussed in detail in Part Three.) The ‘elicitation line’ you will use to provide as an incentive for the secret-keeper to share information will vary depending on the circumstances and the person, but unlike corporations and spy agencies you won’t ever have to bribe the person with money!

In our working lives, we attend meetings, business conferences, trade shows and presentations. We have all learned the benefits of ‘networking,’ which is simply the process of meeting useful contacts for our own, or mutual benefit. In all these situations, people make conversation with each other and remember interesting or useful information. As part of business or personal networking, people are deliberately engaged in conversation with the view to creating useful contacts. You may have noticed a person who is a very effective networker and has developed a diverse array of useful contacts and seems to have an insight into a lot that’s going on. That person has either naturally or purposefully learned elicitation skills. I think it is fair to say that elicitation is part of our everyday lives, and those most effective at it, gain the most advantage and best protection as a result of those skills.

A secret-keeper (business competitor, deceptive client, criminal suspect, staff member, management executive, lying child or student) is likely to refuse to answer our direct and obvious questions about information that is hidden from us. Alternatively, a secret-keeper may not be deliberately hiding the information—it may psychologically be too difficult to tell you the secret information, or to even recall it accurately, e.g. they may be a victim of crime, child or spousal abuse. In both cases the information needs to be elicited from the person. We just need to use different tactics and ‘elicitation lines’ to successfully do this. Elicitation is not about intimidation or coercing information from a person, nor is it about causing the person to fabricate information; it’s about uncovering the truth, that’s wrapped up in a secret form.

If we elicit the information correctly, it will be an enjoyable conversation for both the secret-keeper and the secret-target (that’s you). I’m sure at some stage you have met a person who seems difficult to connect with. The person isn’t deliberately being difficult, it’s just that you seem to be on a different wavelength and communication is difficult, jokes fall flat or the person just doesn’t get you. Similarly, perhaps you’ve met with an overly eager or inexperienced salesperson who seems to be doing all the talking, or you may have been on the phone to a company that seems more interested in validating your identity and selling you something than really listening to what you have to say. These are good examples of exactly the way we don’t want the secret-keeper to feel about their interaction with you.

At some stage you may have met with a person who you thoroughly enjoyed talking with, and felt that you could talk to them all day. Some describe these people as ‘good listeners’. While the person may not have had a hidden agenda of eliciting information from you, they have naturally developed elicitation skills. As a result, you felt very comfortable conversing and may have even shared more detailed information than you would normally and would like to talk with the person again as you enjoyed the person’s company. That is exactly the way we do want secret-keepers to feel about their interaction with you.

Elicitation in Action

On one occasion an agency was investigating a senior member of an outlaw motorcycle gang. Investigators became concerned because the person’s bank accounts and phone had simply stopped being used on the same date. Considering his passport had not been used, he should have been in the country and been able to be located using surveillance operatives. However, there was suddenly no trace of the person, anywhere. There are a number of reasons why all traces of a person’s activities can cease on a particular date. These include being spooked by law enforcement interest and as a result the person starts hiding, the person has left the country using a false passport or has been killed. None of these are favorable outcomes to investigators.

The person had a ‘relatively’ law abiding non-bikie brother who he was close to. It was ascertained the brother would most likely know the suspect’s whereabouts. In this situation, the brother was the secret-keeper. If I were to simply approach the brother and ask direct questions to find out where the suspect was or what had happened, his response would not have been favourable. However, using the READ Model of Elicitation model (discussed later), I approached the brother at his local hotel and spent some time engaging him in conversation about a number of topics. During one of our conversations, he informed me that his brother was on a camping, shooting and fishing trip in an isolated part of Australia.

As this was a place where there were no banks or mobile phone reception, it explained the person’s apparent disappearance. After a suitable time I left the hotel. The brother had clearly enjoyed the conversation and would have welcomed me back had I returned at some stage in the future. When elicitation is conducted correctly, the information from the secret-keeper flows so naturally and so fluidly that the person feels relaxed and comfortable and doesn’t even question why they are sharing so much information with you. That was the case with the bikie’s brother.

From a business perspective some people may ask why use elicitation? Isn’t it enough to simply research all the competitor information from corporate publications and reports on the internet and not have to talk to anyone? A businessperson may spend many hours researching a competitor’s marketing and business strategies to better compete against a particular company. However, the problem even with in-depth research of this nature is that print is only accurate on the day it’s printed, things change constantly, websites aren’t updated regularly and businesses only release the information they want others to know.

On the other hand, humans remain up to date and can provide insight into the human and commercial dynamics of a competitor including concepts and future strategies. It’s an important insight that only a person can provide. In business, skilfully executed elicitation will produce accurate and reliable information that others, who rely on paper and electronic based research, simply cannot learn.

To achieve this we can follow the READ Model of Elicitation (explained in Part Four) to guide us through the process. However, before we move on to that it’s helpful to understand the two categories of elicitation—direct elicitation and indirect elicitation—as there are different elicitation tools applicable to each category.

Direct Elicitation

Direct elicitation can simply be described as an elicitation process where the secret-keeper is aware that you are attempting to learn their hidden information. This can occur in more structured settings, such as an interview-like situation. However, it may also be conducted in a less structured environment; for example, by a parent who is wanting to find out information from their teenager about what they have done or are planning to do without the process seeming like an interrogation.

Direct elicitation is, as the name subjects, a direct approach with obvious questions being asked of the secret-keeper. However, this doesn’t mean that just the conventional question and answer process takes place. We need to apply direct elicitation techniques beyond this to improve our chance of success. In the absence of these techniques, the hidden information would most likely remain so—as the person can simply refuse to answer, or may have difficulty recalling the required information.

Examples of Direct Elicitation

Workplace interviews including:

• Investigation of complaints, accidents or other incidents

• Performance feedback sessions

• Selection panel interviews

• Personnel vetting interviews

• Past employment history checking and referee verification

• Parents or teachers asking children (who perhaps don’t want to implicate their friend/s) about an incident the child witnessed, or possibly to reveal their own misbehavior.

• Welfare situations where parents, teachers, counsellors or medical professionals ask about hidden traumatic information, such as being a victim of crime, road accidents, bullying, grief counselling, etc.

• Medical practitioners asking patients questions about information the patient may not want to volunteer freely, such as illegal drug use, smoking, hidden eating disorders, excessive drinking, etc.

• Police officers, investigators and security personnel questioning a suspect, informant or witness

As you can see, direct elicitation is used in any situation where the person has hidden information and is aware you are seeking that information.

Direct Elicitation Techniques

Most effective elicitation techniques can be applied to both direct and indirect elicitation situations. However, there are some techniques that are specifically very effective when you are in a position of power and are asking direct questions to access the information you require. Direct elicitation techniques include:

• Avoiding a stalemate: Asking questions with ‘wriggle room’ so the person doesn’t back themself into a corner.

• Dissolving authority barriers and demonstrating emotional empathy: To quickly build rapport with the person and have them open up to you.

• Asking open-ended questions: So the person cannot shut the conversation down with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer.

• Using silence: To cause the person to speak.

These four techniques work very effectively with the READ Model of Elicitation and are further explained below together with some examples.

Avoiding Stalemate—Asking Questions with Wriggle Room

In an interview-type situation, there is a tendency to ask a direct question to get to the bottom of the matter. However, often such an approach is simply met with a refusal or a stubborn denial and it can extinguish the person’s motivation to communicate. This unproductively positions the two people in opposing corners creating a stalemate.

Stalemates

Parent/teacher: ‘Tell me who threw the ball through the window?’

Child/student (secret-keeper): ‘I don’t know.’

Workplace accident investigator: ‘Did you leave the floor wet?’

Suspect (secret-keeper): ‘No.’

Shop assistant (clothing being returned): ‘Have you worn this item?’

Purchaser (secret-keeper): ‘No.’

In these situations, the secret-keepers are now locked into their story and they can’t deviate from this or it will reveal that they have lied, causing them embarrassment, loss of face, ridicule, or even facing a penalty or punishment. So a conversational stalemate is reached. When two people are firmly locked in opposing corners, there is a total communications breakdown and it can be very difficult to overcome.

Nothing will lock a secret-keeper’s information more securely than if you ask a question that forces the person to blatantly lie. This locks them into a ‘denial corner’. Once in that corner, they cannot tell the truth without exposing themselves as having lied.

Once a secret-keeper is committed to an outright denial, it takes a lot of psychological pressure before the person will capitulate and come clean with the truth.

We don’t want to enter into a battle with the person’s ego or pride, so the trick here is to strike before they lie themselves into the corner. We do this by asking questions with ‘wriggle room’ so the person may tell at least a half-truth. This is usually wrapped up in a vague answer rather than an outright lie or denial. It’s fine if the person lies about one aspect of the matter but gives you some truthful information. You can then work on the truthful aspect to access the whole truth later in the conversation, without the secret-keeper feeling like s/he have been exposed as a liar.

Allowing for wriggle room

Using the same scenarios as in the examples above, but rephrasing the questions to allow wriggle room.

Parent/teacher: ‘Do you think you could help me find out who threw the ball through the window?’ (Even if this is met with a vague denial, the child hasn’t blatantly denied any knowledge, so later in the conversation, if the child does give some information, it doesn’t come at the cost of being seen as a liar—therefore it is more likely the child will be forthcoming.)

Child/student: ‘I don’t think I can.’ (This is a much better response than an outright ‘no,’ so the parent/teacher can then work with the child to elicit what actually happened.)

Workplace accident investigator: ‘Have you received training on how to clean up safely in the workplace?’ (This allows the person a ‘loop hole’ that may excuse them to some degree for leaving the floor wet. It doesn’t change the facts of the incident being investigated, but a question such as this is more likely to lead to a confession later in the conversation.)

Suspect: ‘Well, I’ve cleaned up plenty of times, but I’ve never actually been trained.’

Shop assistant (clothing being returned): ‘This appears to have been worn. Do you think someone wore it before you bought it?’

Purchaser: ‘It’s possible; maybe that did happen.’ (This provides a loop hole for the purchaser and allows some wriggle room in the answer. At this point the purchaser has admitted the clothing has been worn—that’s a crucial gain. The next step is to ask how could it be that the ‘worn condition’ of the clothing wasn’t picked up at point of sale by the purchaser or the checkout assistant; as the questions slowly close the loop hole towards an admission.)

A conversational stalemate is the greatest enemy of uncovering hidden information; it simply stalls the flow of all information. This is the worst situation and should be avoided by asking questions with ‘wriggle room,’ that frees the flow of both true and untrue information.

Any conversation, even one laced with lies, is better than an outright denial. The solution is to ask questions with wriggle room; allowing the secret-keeper to tell both some truth and some lies—before they can make a total denial.

Dissolve Authoritative Barriers and Demonstrate Emotional Empathy

In the previous list of direct elicitation examples, you may have noticed that the person seeking the hidden information is usually (not always) in a position of authority, by position, expertise or profession, over the secret-keeper. If you are in an authoritative position when seeking information from a secret-keeper, the biggest disadvantage in those situations is that your position differentiates you (or sets you apart) from the secret-keeper. This sets up an immediate communications barrier that needs to be overcome in order to have the information shared. A communications barrier of this nature can cause an intellectual tug-of-war between knowledge (that they have) and power (that you have).

To better understand this concept, let’s consider an example where an insurance company investigator needs to question a businessman (the secret-keeper) about a suspicious fire at his business. In this situation the insurance company investigator has a clear power advantage over the secret-keeper because if the investigator believes the businessman was involved in setting the fire, the claim may be refused or at least stalled. Regardless of whether the businessman is guilty or innocent, there is an intrinsic authoritative advantage weighted in favor of the investigator in this relationship; more so if the businessman is actually guilty.

For the sake of the example, let’s consider the secret-keeper (businessman) is innocent. He has lost everything in the fire, been questioned by the police, by fire investigators and possibly the media. The businessman has had his entire life upturned and every aspect invaded by the authorities and now the insurance investigator is asking more questions. The person feels their private life as well as their business life has been trespassed on and he has suffered a distinct lack of privacy.

Despite the fact the person is innocent, he may not want to share any more information, particularly with yet another authoritative figure. The investigator just wants an accurate and truthful account of the circumstances. In this situation, even where the secret-keeper is innocent, if the investigator doesn’t break down the communications barrier caused by the inherent authority difference, it’s unlikely all will be revealed; it most definitely won’t be revealed if the person were guilty of setting the fire.

Some people may consider the best way forward is for the insurance investigator to use their authority to force the secret-keeper to reveal the information; in this example, the threat of refusing or stalling an insurance payout may be held over the businessman’s head. In some cases a stern approach can be a valid technique, in measured amounts in some circumstances. However, I don’t support this approach as it rarely produces the most accurate and full account of circumstances. It usually results in half-truths and minimal information is provided by the secret-keeper to mitigate the threat. Once the threat is reduced the information stops flowing. We want voluntary and free flowing information to be forthcoming and threats rarely produce this.

Similarly teachers and parents can’t yell at a troubled child and expect a deep and troubling secret to be revealed, fully and honestly. It may upset the child and some information may forcibly be revealed, but not fully and usually not accurately.

One of the main reasons why evidence obtained by the police under a threat is inadmissible in court is that pressuring and coercing information from people rarely works and, when it does, the information is inherently inaccurate and unreliable. The ineffectiveness of demanding and coercing information was highlighted in a study that sought the views and experiences of murderers and sexual offenders when interviewed by the police.52

The research compared two investigation styles used by the police; one dominating and forceful, and the other where the police approached the interview in a more humane and understanding way—communicating empathy and a genuine interest in the suspect and their predicament. The research was conclusive. More admissions were elicited as a result of the latter technique and less through forceful and coercive means, which only served to increase the number of lies and denials.

It was clear that even criminal offenders responded favorably and revealed their secrets when dealt with in a compassionate and understanding way. The results of this study have been replicated in several other similar studies and the majority of data indicates the ideal interviewer/elicitor is a person who can convey a range of emotions including empathy and sincerity during the information gathering process.53 The consistent message here is that through positive verbal rapport and a demonstration of emotional empathy, even the most abhorrent offenders will reveal their secrets and willingly communicate the truth—even if it means going to gaol!

If murderers and sex offenders are prepared to confess incriminating evidence and in doing so ensure their conviction, then surely we can have others who don’t face a gaol sentence tell us their hidden information? Yes we can; we just need to create the correct environment and a relationship that is conducive for information sharing and a major part of this is demonstrating empathy. Empathy is the identification with and understanding of another’s situation, feelings and motives.54 It’s not sympathy; it’s understanding the feelings of the other person.

In fact, research has shown that in police interviews, rapport building through empathy and sincerity increased cooperation in interviews and also the accuracy of recalled facts by 35–45%.55 Regardless of the circumstances, when you are seeking hidden information from a position of authority or power, you will be more successful if you reduce the communications barriers and demonstrate empathy and sincerity.

Continuing with our example, if the insurance investigator (Dianne Johnson) introduced herself to the businessman like this, ‘Hi, I’m Investigator Johnson. I need to ask you a few questions about the fire,’ there are three immediate barriers created by that very first sentence.

• An authoritative barrier, by using the title ‘investigator’

• A personal barrier, by using the surname ‘Johnson’

• An emotional barrier, by a lack of empathy

This introduction drips with formality and authority and lacks emotional empathy which extinguishes any real potential for rapport with the secret-keeper; a vital ingredient in all elicitation processes. A simple change in that first sentence can set the wheels of rapport turning and may lead to the businessman providing not only just the required information, but much more.

A simple introduction of ‘Hi, my name’s Dianne. I work for Mackay Insurance. I’m sorry for your loss. Would you be willing to help me with some information?’ would initiate a cooperative conversation and open the doors to hidden information far more effectively than an authoritative, officious and emotionally cold approach.

Even if the investigator suspects the businessman is guilty, it’s important to erase the authority barrier verbally and show an emotional link through empathy. This is quickly done by dispensing the use of the ‘investigator’ title and using a first name only. The investigator’s authority is inherent in the relationship and there is no advantage in reinforcing this verbally. If the businessman is guilty his guard may be lowered through a more empathetic approach as he won’t feel like he is a suspect. If he is innocent there is an immediate emotional link with the insurance investigator, who has clearly demonstrated an understanding of the secret-keeper’s predicament.

While this scenario used an insurance investigator, it could easily be a parent, doctor, teacher, counsellor, university lecturer or lawyer; in fact any situation where the secret-keeper perceives there is a difference in authority.

In direct elicitation situations, by relying upon professional expertise or positional authority, it’s sometimes very easy to become adversarial with the person. This can very quickly result in a question and answer interview which won’t produce the required full and accurate information. In these situations, first assess how you can dissolve any existing authoritative barrier and look for a way to demonstrate that you understand how the person feels; this will encourage a much more positive flow of hidden information.

Rapport is created through similarities; always minimise your differences and emphasise (even exaggerate) your similarities. Building a close rapport with a secret-keeper is the single most important element influencing whether a person will share hidden information.

Open-ended Questions

In direct elicitation situations, questions to be avoided are ones that result in a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer. When people are asked too many questions that simply require a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response, the interaction quickly feels invasive or like an interrogation. Understandably, this can reduce their motivation for cooperation. Questions that result in a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer are called ‘closed questions’ and while they do provide us some information, we want to elicit a lot more.

We want to use open-ended questions that evoke a response of some length from the secret-keeper—the longer the better. Research has shown that open-ended questions elicit longer and more detailed responses in police interviews.56 These types of questions are gateways to conversations and evoke a response filled with information and importantly avoid the ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer a closed question usually results in. Open-ended questions coax people to speak; it allows them an opportunity to tell you their story. These types of questions usually commence with single words or phrases such as:

• Who—Who were you with?

• What—What happened then?

• Why—Why did that happen?

• Where—Where did that information come from?

• When—When did the program commence?

• How—How did you meet?

• Can you tell me …?

• Would you be able to explain …?

As you can see, it’s difficult to answer any of these questions with a blunt ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and places a conversational onus on the secret-keeper to give longer answers.

Closed versus Open-ended Questions

| Closed | Open-ended |

|

Parent: ‘Did you go to the mall after school today?’ Teenager: ‘Yes’ Parent: ‘Did you meet anyone there?’ Teenager: ‘Yes’ Parent: ‘Was it one of your friends?’ Teenager: ‘Yes’ |

Parent: ‘Can you tell me what you did after school today?’ Teenager: ‘I went to the mall.’ Parent: ‘What did you do there?’ Teenager: ‘I met Mike and Dominique.’ Parent: ‘What did you do then?’ |

|

Job interviewer: ‘Are you a hard worker?’ Applicant: ‘Yes’ Job Interviewer: ‘Do you use initiative?’ Applicant: ‘Yes.’ Job Interviewer: ‘If you are hired, will you perform well?’ Applicant: ‘Yes.’ |

Job interviewer: ‘Can you describe your work ethic?’ Applicant: ‘I’m a conscientious person who is punctual and dedicated to my role.’ Job interviewer: ‘If you are hired, how will you be able to help the company?’ |

|

Welfare counsellor: ‘Have you done much since we last met?’ Patient: ‘No.’ Or, Welfare counsellor: ‘Did that make you feel angry?’ Patient: ‘Yes’ |

Welfare counsellor: ‘Tell me what has happened since we last met.’ Patient: ‘Well …’ Or, Welfare counsellor: ‘Can you explain how you felt when you saw that?’ Patient: ‘Well …’ |

Before you ask a question in a direct elicitation situation, run it through your mind and assess if the answer can be ‘yes’ or ‘no’. If it can be, simply rephrase it as an open-ended question.

Using Silence

On one occasion, a seasoned covert operative played me a recording of his very first undercover meeting. The meeting, during which he was to elicit particular information from a high-value target, took a long time to arrange, was resource intensive and was critical to the success of their overseas operation. The 20-minute recording of the meeting was full of clearly recorded conversation. The only problem was, the newly trained and very nervous covert operative babbled away constantly at the suspect throughout the entire meeting. The suspect barely said anything—he didn’t have a chance! The conversation was full of the operative’s valiant attempts at eliciting hidden information and they were technically well executed; if only he had stopped talking, the secret information would have flowed freely.57

This is not confined to cloak and dagger environments. Similar to the covert operative’s unsuccessful elicitation attempt, a doctor or specialist who talks through most of the consultation and doesn’t pause to listen to the patient is most likely to get the diagnosis wrong. This is not because of a lack medical expertise, but through conversational ineptitude. In addition to permitting an increase in the amount of patient information to assist with the diagnostic process, deliberate pauses by the doctor or specialist also allows an adequate time for the patient (secret-keeper) to mentally process a question and to provide a more cohesive response.

The more you talk when trying to elicit information, the less opportunity there is for the secret-keeper to share the hidden information. During any conversation, no one likes to be interrupted or, worse still, to have their sentences completed for them. After asking an open-ended question or setting your conversational ‘hook’ (discussed later in Part Three), it’s best to pause, allow the secret-keeper to talk and take the position of being a good listener.

Most people will consider you are a great conversationalist if you simply ask questions and then listen to them do all the talking! People will naturally ‘like’ you if you give them a chance to be heard and actively listen and comment on what they have to say. People share more information with people they like.

So we’ve seen that silence can be a valuable tool to allow the secret-keeper to share information in a direct elicitation situation. Additionally, silence may also be used also to cause the secret-keeper to reveal information. When there is a silent pause in a conversation, people feel compelled to fill it with words (or even sounds!). You may have been to a presentation or event where a public speaker uses umms and ahs at the end of each sentence before commencing another. The primary reason for this is to avoid the deafening and uncomfortable silence. Silence may provoke a person in the audience to interrupt or make comment while the presenter is thinking of what to say next, so the person fills the space with umm and ah sounds. This allows the presenter to maintain conversational control as silence can be perceived as a conversational pass to another person, whose turn it is then to speak.

We have all been in situations where there is an awkward silence or pause during a conversation. The fact is, we simply don’t enjoy pregnant pauses in these situations. When there is such a pause, one of the two people in the conversation will speak purely to relieve the uncomfortable silence; that person was forced into responding.

Using this phenomenon we can maintain our silence to provoke the secret-keeper to speak. Pauses are an important part of dialogue and ‘pausing for effect’ can be a useful tool in elicitation. Not just for emphasis, but importantly as a tool to encourage the secret-keeper to talk. Research has shown that the length of tolerable pauses in conversations varies between languages, cultures and the individuals engaged in the conversation. Broadly speaking, though, most of us can only tolerate pauses of two or three seconds before one of us simply has to speak.

A lengthy pause puts pressure on both people in the conversation. When a speaker finishes a sentence and then pauses and looks to the listener, the listener is under pressure to respond. If the speaker completes a statement and then the listener says nothing, the speaker will start to wonder if they have offended the listener or said something incorrect and will often clarify what they have said or add additional information. It is the latter example that is of real use when eliciting information.

When the secret-keeper tells you something, deliberately insert a pause. This provides little feedback to the secret-keeper and will create some psychological pressure to speak again. Keep in mind, though, that this technique should only be used sparingly as it can make the secret-keeper feel uncomfortable talking with you and may counter your rapport building efforts.

Indirect Elicitation

Indirect elicitation is, by its very nature, a more surreptitious activity than direct elicitation. With direct elicitation, secret-keepers are aware that you are attempting to obtain information and know they are being questioned, interviewed or asked about a particular issue. In contrast, one of the primary goals of indirect elicitation is to obtain information from people without them being aware. Unless a person has been specifically trained in counter-elicitation, or is extremely private and introverted, indirect elicitation is an effective tool on most people. By investing time and using a variety of techniques over a series of well-engineered conversations, it’s possible to access most people’s hidden information.

Some people may feel this all sounds sneaky and a bit untoward. Well, a book that’s called Unlocking Secrets is bound to be a bit that way! In many elicitation processes there is a necessary element of deceit. However, it rarely goes beyond making simple conversational statements such as telling the secret-keeper that you like something or agreeing with their opinion when in fact you don’t. These ‘little white lies’ occur as part of normal conversations every day, as people seek to cooperate and not offend others, e.g. ‘Yes, I do like your new hair style’ or ‘Yes, you look like you’ve lost weight.’58

People are motivated to say these types of things so they don’t unnecessarily offend a person. The only difference between this everyday deception and deception in elicitation is the motivation to create a relationship or a conversation for the purpose of learning hidden information.

Years ago when body language became the new frontier of interpersonal communications, some people considered the deliberate use of techniques such as ‘mirroring’ a person’s body position, or deliberately using open body language techniques etc., to increase communication or feign interest in a conversation was also untoward.

Indirect elicitation is not a sinister practice, and it can form an important and proper part of parenting, teaching or business acumen as well as a person’s social life. For example, parents often demand information on the spot from their child if they suspect the child of wrong-doing. Even if the parent uses the direct elicitation techniques discussed earlier, these attempts may fail. When a parent suspects a child is ‘up to no good,’ they rarely adopt a tailored strategy over a couple of conversations that will induce the child to tell-all. Conducted correctly, indirect elicitation can do this.

In a social context, indirect elicitation techniques may also be used as a dating tool to create a personal bond with another person very quickly. In business, indirect elicitation can identify when a competing company is making major decisions, its marketing strategies, secretly planned HR changes, or positive opportunities such as company expansion and impending promotional opportunities. Indirect elicitation can provide both protection and a vital personal or professional edge to the user.

Some professionals who teach elicitation to covert operatives would have you believe that it can only be conducted by experts and is far too complex for everyday people. I agree that indirect elicitation can be a very complex process, which is why I’ve designed the easy-to-follow READ Model of Elicitation. However, I disagree that everyday people can’t be effective at unlocking secrets. All that is required is:

• Average intelligence

• Average interpersonal skills—a person with excellent interpersonal skills, or who likes talking to, or meeting new people will do extremely well

• Average self-confidence

• People observation skills—people who are perceptive of others or like watching other people (not stalkers!) will likely excel

• Life experience (age is an advantage; it’s difficult for children to learn and apply these skills)

• A willingness to learn some basic knowledge and techniques (shown in this book)

• A preparedness to talk to people and to practise these skills

If you don’t tick all these boxes, don’t worry. I’ve seen some quite introverted people excel at elicitation simply with a bit of technical knowledge and some practice.

Indirect Elicitation Examples

• Meeting a competitor (secret-keeper) at a trade show or conference and having the person tell you some inside information to advantage your business.

• Police officer, workplace investigator, lawyer or private investigator eliciting additional information from a suspect, witness, or informant.

• Doctor, nurse, paramedic or welfare councillor using these skills to have a patient or client recall information that is suppressed or difficult for the person to manage.

• A negotiator may elicit vital information from the other side during apparent casual conversations

• In sales, these skills can be well utilized by both the retailer and the customer. The retailer may learn a great deal about the customer and then tailor the sales pitch accordingly to increase the chance of a sale. Similarly, the customer may use these skills to elicit information about the ‘real’ lowest price the item can be purchased for.

• A person considering purchasing a house may use indirect elicitation when speaking with other residents in the area to find out what it’s really like living in that district.

• A parent may use these skills on another person when assessing that person’s suitability to provide day care or private tuition for their child.

These are just some examples of where indirect elicitation may be used to advantage. However, the spectrum of where these skills may be utilized is only limited by the imagination.

In summary, indirect elicitation may be applied in any situation where you want to learn information from other people without them knowing.

Indirect Elicitation Techniques

In this section, we’ll look at the most successful indirect elicitation technique aimed at subtly encouraging a secret-keeper to divulge their hidden information. It’s called, ‘being that person’ and we’ll learn how to do this using ‘likeability,’ ‘emotional linking’ and ‘psychological mirroring’.

‘Being That Person’ using Likeability, Emotional Linking and Psychological Mirroring

As we have seen, some of the core skills used by spies and covert operatives are directly transferable to a variety of situations which can advantage and protect everyday people. Unlike spies, we can’t (or shouldn’t!) inject truth drugs such as sodium pentothal and sodium amytal to ‘free the tongues’ of people—but we can use conversational techniques and ‘elicitation lines’ that encourage a person to willingly and voluntarily share accurate information with us.

Fortunately, there are some aspects of human nature and secret-keeping that can assist us with this. For example, when a person has a secret there is an inherent and natural urge to want to share that information. Information sharing is our human default setting. In fact, it’s rare that people will not tell at least one other person their hidden information; often they tell more than one person. This has been evidenced in recent research that verified very few people keep secrets just to themselves.59 It is extremely rare that a person will not share. One study identified that in 87–96% of cases, people shared their emotional experiences rather than keeping them a secret.60

The urge to share is a natural desire to seek another perspective and gain some psychological relief by ‘offloading’ the information. This makes it difficult for people to keep secret information solely to themselves. So, in the correct circumstances, a secret will be revealed to at least one other person.

If we want to access that information, we need to create an environment and a relationship that encourages such a disclosure to us—we want to ‘be that person’ in the mind of the secret-keeper.

Coaxing not forcing

It’s not possible to ‘be that person’ by being physically or verbally forceful (no thumb screws!). It’s simply not possible to walk up to a business competitor and ask their company’s tender price for a project, or demand to see their client list, nor can a person in the workplace successfully demand a senior manager to tell them the secret management plan for workplace redundancies. These attempts would simply fail.

Similarly, doctors, psychologists and counsellors would have very little success in demanding the most intimate details from clients. This type of information needs to be coaxed from people, even in these professional environments where trust is usually presumed and confidentiality is assured. If you were to visit one of these professionals and felt that they were asking more intimate questions than necessary and, importantly, you didn’t ‘like’ the person, would you share your most confidential information with the specialist, or would you be more guarded? In that situation, many people would feel uncomfortable and not share even though it occurred in an environment where the professional is legally bound to keep information confidential. Why? Because the specialist is not ‘being that person,’ so you would be reticent to fully divulge your secret information.

If we want to ‘be the person’ the secret-keeper confides in, we need to know who secret-keepers confide in. We can then become ‘that person’ in the secret-keeper’s mind. A unique study which examined the aspects of keeping and disclosing secrets of 70 people, provides us some excellent guidance on this very point.61

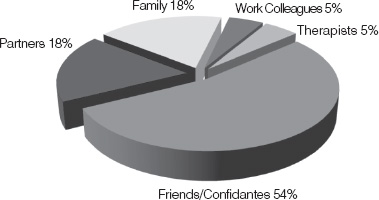

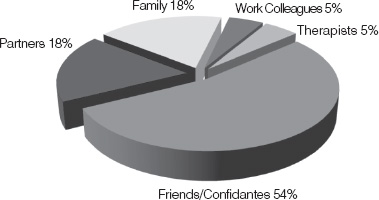

Of the 70 people who filled out the confidential questionnaires 41 stated they had a secret.62 Of those 41, only 4 stated they had not told anyone their hidden information. So, in line with our earlier discussion, about 90% did disclose the information to at least one other person. The results of the study showed that most often, secrets were told to those who the secret-keeper felt emotionally close to. This was usually to ‘friends or confidantes’—less so to people in the categories of family, partners and colleagues. Surprisingly, friends were about three times more likely to be confided in than family members or partners.63

To Whom Secrets are Told64

The fact that friends are confided in most often is good news for us, as it’ll be almost impossible for you to suddenly become related to the secret-keeper and I don’t recommend marrying a person just to access their secret—though it wouldn’t be the first time this has happened in pursuit of international intelligence! However, if you become the secret-keeper’s elicitation friend or confidante it is most likely the person will then share their hidden information.

To become ‘that person’ who is the friend or preferred confidante of the secret-keeper, you need to:

1. Be liked by the secret-keeper.

2. Have an emotional link with the secret-keeper.

Likeability

People share their most intimate and private information with people they ‘like’. The more a secret-keeper likes you, the closer you’ll become to ‘being that person’. Regardless of how good your elicitation line is, if the secret-keeper doesn’t like you, their information will remain locked away from you. Even after meeting very briefly, people get a sense of how they feel about another person very quickly. For this reason, we need to ensure that the first and also the last impression the secret-keeper has of you is a positive one of concurrence, i.e. you both agree on and share something and depart feeling positive about the interaction. This initial action sets the communication platform for that relationship at that particular point in time and will encourage more open and truthful communication to occur subsequently.

Most people have a natural sense of how to be likeable and friendly and most can turn on those charming interpersonal skills when they are required. We learn this from a very young age. Children are very adept at this and can change from demon to demure, from cranky to cute and from naughty to nice in a heartbeat, particularly when they want something! These skills develop as we grow and by the time we reach adulthood most of us are able to be likeable to another person when required, even if it’s just for a short time. Even parking inspectors and debt collectors can be charming if they like … maybe.

Using your natural ability to be ‘likeable’ is a good start for your interaction with the secret-keeper. However, in addition to being liked by the secret-keeper, the fastest way to encourage a person to share information also includes creating an emotional link.

Emotional linking

An emotional link may be formed between two people by a mutual point of interest, a commonality or a similar sense of humor and these are created quickly in situations where both people are in the same situation—and they feel emotionally similar. For example, the secret-keeper and the secret-target are waiting for a long time in a queue, when the secret-target shares how frustrating this is and then cracks a joke about the situation. If the secret-keeper laughs there is an established emotional link. Even if the joke falls flat, psychologically the secret-keeper will still acknowledge (internally) that they share the same emotion (frustration).

People relate better and communicate more effectively with those they consider are similar to themselves. In this case, indicating the same emotion as the secret-keeper demonstrates similarity and creates a subtle mental alliance. In the secret-keeper’s mind, the secret-target thinks similarly and understands the situation the same way as the secret-keeper. This creates an emotional link, not a strong one, but there is a shared emotion between the two and that is a great starting point. When this is done deliberately, it’s called psychological mirroring.

Psychological mirroring

Psychological mirroring works on the well-proven premise that ‘people like people who are like them’. Psychological research demonstrates that people share information more readily with people who have similar characteristics, such as age, values, beliefs and culture.65 This doesn’t mean we can’t communicate or don’t enjoy communicating with people who are different from us, but on most occasions we feel more comfortable divulging information to people who have something in common with us. This human trait is not limited to major characteristics. For example, two people of different cultures may have increased relatedness when one of them highlights that they are both members of the same church, sporting club, or on the same side of politics. However, if one of them was to point out all the differences between them rather than the similarities, close communication becomes difficult and would attenuate the free flow of information!

One study even demonstrated that using similar names on envelopes produced a more positive response from people.66 This study posted questionnaires (asking for a response) to people using a sender’s name similar to the recipient. For example, a questionnaire sent to Joan Read had a (false) sender’s name of John Ready. The study showed that when the recipient’s name was mirrored by the sender details, the return rate increased to 56% from 30% (when the recipient’s name was not mirrored). A significant aspect is that this increase occurred without any interpersonal communication, simply a similar name written on paper. When we use the technique of psychological mirroring in person it’s even more influential!

In a body language context, there is a substantial amount of evidence that ‘physically mirroring’ another person’s body position enhances interpersonal communication. Recent research has demonstrated that behavior mirroring increased trust during negotiations and this led to the ‘mirrored’ person disclosing details more readily to the person who was mirroring, and another study showed that mirroring increased sales from 12.5% to 67%!67

Psychological mirroring takes the body language mirroring concept further and seeks to tap into the psychological bias to favor those that are similar to us. By demonstrating the same emotion as the secret-keeper in the same situation we can establish an emotional link. Unlike body language it’s not just the physical mirroring that is critical; it’s psychological ‘mirroring’ of the secret-keeper.

Psychological mirroring is deliberately demonstrating and sharing the same emotion as the secret-keeper at the same time. This is very effective at creating rapid emotional rapport between two total strangers and frees the flow of information very quickly.

With all elicitation situations it’s important to demonstrate clearly through speech and actions that we understand and, importantly, share the secret-keeper’s emotions about the given situation. Regardless of the circumstances, whether it’s happy, sad, exciting or funny, we need to tune-in to the secret-keeper’s emotions at the time we engage with them and demonstrate our understanding of whatever emotion they are experiencing at that time.

One effective way to do this is by using similar or the same words and phrases as the secret-keeper. For example, if the secret-keeper says, ‘It’s so hot today!,’ your response should be, ‘Yes, you’re right it is really hot.’ Not: ‘Yes, it’s very humid today.’ By using a different term (humidity) the secret-keeper may conclude that you are either showing a different perception of the same situation, or deliberately using a more technical word, as some kind of one-upmanship—both are counter to bringing the secret-keeper closer to us.

Repeating words or phrases used by the secret-keeper during the conversation reinforces the similarities between you.

If you reflect upon your past experiences, there may have been an occasion when you were in a group of strangers and for some reason you all shared the same emotional experience. Perhaps, you may have been waiting for hours in an airport departure lounge, or been on a bus or aircraft that broke down or was diverted. Perhaps you were seated next to another person in a restaurant when the two of you each had to wait a very long time for your meals to arrive. If a stranger in the same situation as you was nice to you, i.e. while in the departure lounge they lent you a magazine or mobile phone to contact relatives about your later arrival time, and the stranger was empathetic (showing they shared the same feelings about the situation), and days later you saw each other again would you still be strangers? I suspect if you met on a second occasion, there would be, a nod, a slight smile or at least a minor acknowledgement as there is now a kinship (albeit weak) between you. You like the person because of the kind gesture and you have an emotional link as you both felt the same emotion about the same situation at the same time.

In situations like this people feel psychologically similar and on the same side against a common adversity. Even smokers who, through their working day stand outside the workplace in rejected groups, form an emotional bond and share information more readily as a result. Strangely enough, some lifelong friendships have been born out of these types of situations! They provide a similar experience to team building exercises which are aimed at creating bonds through shared experiences.

In a different context, camaraderie is very quickly formed with police, emergency services workers and military personnel when dealing with tragic and personally testing experiences, because they traverse through the same emotions together and form a close emotional bond. Psychological mirroring replicates this.

Regardless of whether it’s a positive or a negative experience, it’s critical for us to overtly and clearly demonstrate our ‘shared’ emotional experience, because (in the secret-keeper’s mind), it brings the secret-keeper emotionally closer to us. This enhances the relationship rapport and paves the way for closer, more intimate communications.

Psychological mirroring: Two mirrors in a lift

On one occasion I was in an elevator with a number of people, including an elderly lady and a suited businessman, when the lift inexplicably stopped. No one likes being stuck in a lift and this situation affects different people differently. We waited in silence for a few minutes, hoping the lift would spring to life again. When it didn’t, one of the other people used the elevator phone to contact security, who promised a technician would have the elevator mobile again shortly.

After a few minutes, on my left, the elderly lady began showing signs of fear and anxiety and on my right the businessman was already making huffing sounds and regularly checking his watch; clearly he needed to be somewhere by a particular time. Apart from a minor time inconvenience, being stuck in the lift had no impact on me. Regardless, I turned to the elderly lady and told her that I get a bit tense in situations like this as it’s a bit unsettling (psychological mirror one). She told me that she also felt that way. I told her that I think a lot of people feel that way (normalising statement), but really there was little to be worried about and shortly we’d all be on our way (reassurance). The elderly lady gave me a genuine smile.68

Moments later, I turned to the businessman and adjusted my psychological mirror and told him that I hated things like this happening and that it was a real inconvenience as I was on my way to a specialist’s appointment and now I may be late. He remained stony faced, but agreed and said he was on his way to the airport. I complained to him that I don’t know why in the 21st century we can’t make shopping trolleys that go straight or lifts that don’t break down. After a few more exchanges, I could see his mood lifting. So I adjusted my mirror to reflect this in my conversation with him by making less cynical and more light-hearted comments. His mood improved further.

A short time later, the lift technician’s voice came through the speaker in the wall next to the businessman and told us all that we would be moving in a few minutes. I then asked the businessman if he could order me a cheeseburger meal (as if it were a McDonald’s drive through speaker) and this really amused him. Then, without prompting, he started telling me how important it was for him to make his flight as he had a meeting with a prospective investor. Through psychological mirroring, in his mind we were on the same emotional journey starting with frustration and ending with humor. Now he wasn’t a secret-keeper as far as I was concerned, as I had no interest in what his business plans were—but if I was, this would have been a great way to start eliciting information from him.

A few moments later the elevator started to move and everyone’s mood lifted. As we all exited, despite the fact that he was running late the businessman took the time to say goodbye. Then he extended his hand and we shook hands. Fifteen minutes earlier we got into a lift and he didn’t acknowledge me or anyone else. Now he wanted to shake hands with a stranger when he was late to the airport. Why? Because we were no longer strangers;we had an emotional link created by psychological mirroring.

If we had met again shortly after this incident, our conversation would have started more as friends than strangers, though this would decay with the passing of time. To make sure we started a new interaction as warmly as the other one concluded I would use an elicitation hook and elicitation syncher (explained in Part Three). For example, a hook of ‘Have you been caught in any lifts lately?’ would immediately get his attention. Then I’d select an elicitation syncher such as ‘So have you got my cheeseburger yet?’ This would tie our new conversation directly to the humorous incident and the positive emotional link that formed in the elevator.

As I left the building, I said goodbye to the elderly lady, who then thanked me for helping her. She was clearly never a secret-keeper from my perspective and I used psychological mirroring to comfort her. Nevertheless, an emotional link had been formed between us.

In summary, people share hidden information with at least one other person. With indirect elicitation, if you can be ‘likeable’ and successfully psychologically mirror a secret-keeper by demonstrating your shared emotional experience, an emotional link will be formed and you will be well on the way to ‘being that person’.