The King’s Edict in Behalf of the Jews (8:1–17)

The estate of Haman (8:1). When someone betrayed the king, their property was forfeited. Herodotus reports that the estate of a traitor named Oroetes became the property of the state.173 Josephus writes that Cyrus decreed that anyone who did not obey his laws concerning the Jews would be crucified and their estates confiscated by the Persian government.174 Haman’s estate had become Xerxes’, and he could do with it as he pleased. He chose to give it to Esther, either in compensation for her grief or as an expression of his royal favor.

Scene from the Book of Esther at the Dura Europos synagogue, 3rd c. A.D.

Z. Radovan/www.BibleLandPictures.com

Took off his signet ring … and presented it to Mordecai (8:2). Mordecai was installed in Haman’s vacant office, making him “second to the king” (10:3). Evidence of a Jew named Mordecai serving in a high position in Xerxes’ kingdom has not yet been found. There has been much speculation about whether our Mordecai can be identified with a finance officer of the same name mentioned in a cuneiform document found in Babylon. Some scholars believe it would be highly unlikely for two individuals of the same name to be serving in positions of authority in Xerxes’ government.175 The weakness with this identification is that the Mordecai (Marduka) of the cuneiform text is identified as part of the entourage of Ushtanna, the satrap of Babylon. Since satraps resided in the areas over which they presided, this Mordecai could not have been a resident of Susa, as is the Mordecai in the book of Esther.176 But neither can we say that this is definitely not the same figure, since Mordecai could have moved to Susa after serving in Babylon. All the same, the name Mordecai is attested in several other ancient documents, and the appearance of the name in two contemporaneous documents does not demand that they refer to the same person.

Royal secretaries (8:9). The Hebrew term is sōpēr, usually translated “scribe.” In this era when literacy was still rare, people skilled in reading and writing were much in demand. This was especially true in Achaemenid Persia, where several languages were regularly used in correspondence and inscriptions, including Old Persian, Elamite, Akkadian, and Aramaic. Aramaic could be written with a quill on parchment or papyrus, but the other languages were inscribed on clay tablets in cuneiform characters.

Egyptian scribe

Z. Radovan/www.BibleLandPictures.com

Scribes came from various social strata, and some were actually slaves, specially trained for their literary duties. Many were employed by the temples or the royal court, but private individuals would also employ scribes to draw up contracts.177 Nonetheless, since the acquisition of literary skills required a certain amount of competency, scribes’ responsibilities often extended beyond just transcription. Frequently, they functioned as officers of the king or of the satraps by whom they were employed. Thus, we often find records of scribes not only given the responsibility of writing out orders but of making sure that they were carried out as well.178

The twenty-third day of the third month (8:9). That is, May-June. Seventy days have elapsed since Haman cast lots to determine the day of the Jews’ destruction (3:7). Esther’s first banquet occurred only three days after Mordecai had informed her of Haman’s decree (5:1–4). Either there was a gap of many days between Haman’s decree and Mordecai’s talk with Esther, or more than two months passed after Haman’s death before the order was written to overturn his evil design.

Mounted couriers (8:10). See comment on 1:22.

Right to assemble (8:11). Since the king’s first decree could not be revoked (1:19), this decree was designed to ameliorate its effects. We can assume that the Jews would have defended themselves against those who tried to kill them. But this decree specifically gave the Jews the right to “assemble.” The Hebrew term used here often means to muster an army (e.g., 2 Sam. 20:2; 21:5, 8; Ezek. 16:40, and elsewhere). Thus, the Jews are authorized to begin gathering and arming soldiers to defend themselves against Haman’s mercenaries. Without such a decree, mustering an army would have been viewed as an act of rebellion. This decree was sent everywhere (8:9), which would presumably discourage anyone from attacking the Jews, knowing that they would be prepared to defend themselves.

Thirteenth day of the twelfth month (8:12). That is, on the day appointed for the Jews’ annihilation (see comment on 3:7).

Wearing royal garments (8:15). Not the king’s robes, but robes that had been awarded to him by the king (see comment on 6:8). The “purple robe” is noteworthy, since Cyrus is specifically said to have worn such a garment.179 Golden crowns are frequently listed among the gifts presented to the Persian kings by their subjects, but seldom are they named among gifts given by the king to his nobles.180 Herodotus notes one exception, who tells us that Xerxes awarded a golden crown to the helmsman of a Phoenician ship that had carried the king through a bad storm. Unfortunately, the man did not wear it for long. Since many Persian soldiers had been lost in the rescue, Xerxes ordered the helmsman to be beheaded.181

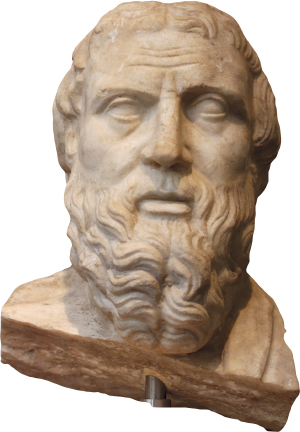

Herodotus

Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia Commons, courtesy of the Louvre

Many … became Jews (8:17). The verb translated “became Jews” occurs nowhere else in the Old Testament, but there is little question about its translation. Its significance, however, is more problematic. What was the fear of the Jews that had seized them? Does the text mean only that many Gentiles sided with the Jews in order to avoid destruction? This interpretation seems unlikely. The lives of the Gentiles were not endangered; the Jews were authorized to kill only those who attacked them. Or is the idea here that the Gentiles were so impressed by the rise of Esther and Mordecai that they converted to Judaism? (This was the understanding of the LXX, where the verb “became Jewish” is translated into Greek as perietemonto, “were circumcised.”) In this case, the converts could be compared to the harlot Rahab, whose fear of the Israelites caused her to worship their God (Josh. 2:11).

Likewise, in the apocryphal book of Judith, an Ammonite becomes a believer in the Lord when he sees how the Jews had conquered the Assyrians (Judith 14:10). But to the rabbis, such converts were like the “lion proselytes” of Samaria, those who adopted the Jewish faith because of their fear of the lions in the land (2 Kings 17:24–28).182 Such conversions, the rabbis believed, were suspect.

Even though the Jews may have been conscious of the biblical injunction to be a “light to the Gentiles,” there is little evidence that they were actively seeking proselytes in this era. While they accepted those who wished to adhere to their faith, there is no evidence that the Jewish people were preaching or engaging in activities designed to convert Gentiles. Stories of Gentiles converting to Judaism were meant to demonstrate the superiority of Judaism to Jewish readers rather than to encourage Gentiles to adopt Judaism.183