Job

by Izak Cornelius

Grieving Job and his friends (painting by Eberhard Wächter [1762–1852])

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY

Introduction

Central to the book of Job is the question of human suffering and especially why people who are seemingly innocent suffer, which in turn raises the question about the righteousness of a loving God. This book deals with the question of retribution, the popular theology according to which the righteous prosper but the wicked suffer, as well as the justice of the deity (the so-called question of theodicy). Job’s suffering, along with his patience (see, e.g., Jas. 5:11), has become proverbial in everyday speech. The problems addressed by this book are truly part of universal human experience and therefore of world literature.1

Date

The date of the story remains a problem. Opinions range from the time of the patriarchs in the second millennium B.C. to the Persian period in the fourth century B.C.; the seventh to the fifth centuries B.C. have also been proposed. The differences between the main part and the prologue (chs. 1–2) and epilogue (ch. 42) make dating even more difficult. Because the term śāṭān occurs with the definite article and is not yet a proper name, the book of Job may be earlier than Chronicles.2

Job is mentioned as an ancient hero (with Noah and Daniel) in Ezekiel 14:14, 20. Noah is the flood hero from the time before the time Abraham (Gen. 6–10), and Daniel (Danʾel) is known from the Late Bronze Age (1350–1190 B.C.) Ugaritic story of Aqhat,3 which indicates that the story may go back to the international lore of the Bronze Age or second millennium B.C.,4 although it could have been written down later and edited in (say) the sixth to fifth centuries B.C.

The Righteous Sufferer in Ancient Near Eastern Literature

Texts dealing with a righteous person who suffers were widespread in the ancient world, especially in the ancient Near East.5 The Egyptian “Dialogue of a Man with His Soul”6 describes someone who asks in his misery whether it would not be better to commit suicide. In texts such as Ipuwer and Merikare, the “discourse of theodicy” receives attention, and the question is asked: “Is a human being incapable of getting influenced against evil and injustice?”7

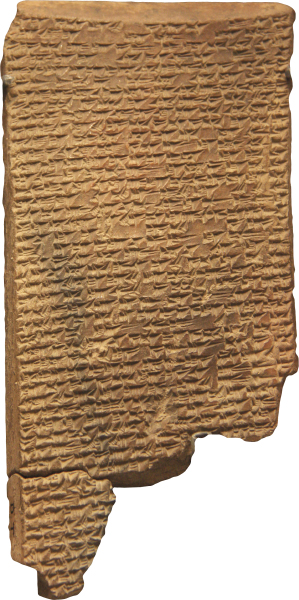

Ludlul bel Nemeqi

Musée du Louvre, Autorisation de photographer et de filmer; © Dr. James C. Martin

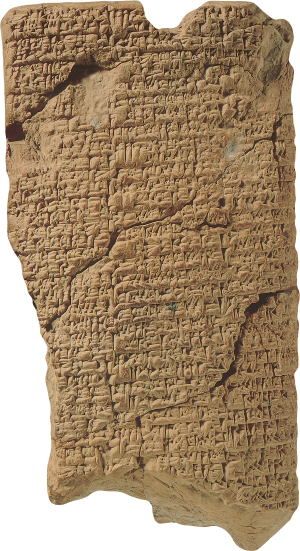

The Mesopotamian material provides us with the closest analogies conceptually, and these texts were also known in a cultural center such as North-Syrian Ugarit.8 The Sumerian A Man and His God,9 which goes back to the beginning of the second millennium B.C., is a long, personal lamenting monologue, in which a pious sufferer has a feeling of guilt. He asks for forgiveness, and the god turns his suffering into joy. The category closest to the book of Job is the Akkadian dialogue, such as the Babylonian Ludlul bel Nemeqi (“I will praise the lord of wisdom”) or the Babylonian Theodicy.10

“Man and his God”

University Museum, University of Pennsylvania

The Ludlul, from the sixteenth to the twelfth centuries B.C., describes a pious but not necessarily innocent person who suffers from an illness, which is described in great detail. He is rejected by his fellow human beings, and even his brother has become his enemy. Ignored by the gods, he summarizes his dilemma:

What seems good to one’s self could be an offence to a god,

What in one’s own heart seems abominable could be good to one’s god.11

The Babylonian Theodicy from around 1000 B.C. comes even closer to the book of Job. It is in the form of a dialogue, and the sufferer, like Job, is in dispute with his friends, although he has only one unnamed friend. There is not that harshness in the dispute that is found in Job. At the end the sufferer expresses the wish:

May the god who has cast me off grant help,

May the goddess who has [forsaken me] take pity.12

The Mesopotamian examples agree that no one is righteous, that suffering is part and parcel of the human condition, and that it is not certain what is right or wrong in the eyes of the gods. Humans cannot fathom the divine mind (cf. Job 11:7–9). This idea was already seen in the part quoted from the Ludlul above. In the Babylonian Theodicy, “divine purpose is as remote as innermost heaven, it is too difficult to understand.”13 And in the Dialogue of Pessimism we read, “Who is tall enough to ascend to the heavens? Who is broad enough to encompass the earth?”14

In the polytheistic religions of the ancient Near East, innocent suffering could be attributed to another deity, as is also stated by some of the texts. There were protective deities to whom one could turn when the main deities could no longer be relied upon. For Job the situation is more complicated: If there is only one God, what if he has become your enemy? At the end Job comes to the insight:

My ears had heard of you

but now my eyes have seen you.

Therefore I despise myself

and repent in dust and ashes. (42:5–6)