FORENSIC ANTHROPOLOGY is the study of the human skeleton and of the facts it can reveal about the age, sex, health, physical condition, cause of death, and time of death of the person once intimately connected to it. With luck there will be enough information in the bones to identify the person and, in cases of homicide, to suggest a possible perpetrator.

The man considered to be the father of American forensic anthropology is Thomas Dwight (1843–1911), whom the New York Times once called “America’s foremost anatomist.” Dwight was the Parkman Professor of Anatomy at Harvard from 1883 until his death. Perhaps the source of Dwight’s interest in the forensic aspect of his profession was the 1849 murder of the same Parkman who had endowed the chair of anatomy he himself occupied. At the time of Parkman’s death, the chair he had endowed was held by Oliver Wendell Holmes, father of the jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes who would become one of the great Supreme Court justices of the twentieth century.

In 1850 John White Webster, M.A., M.D., and a professor of anatomy, had the distinction of becoming the first Harvard professor ever to be hanged for murder. The victim, Dr. George Parkman, has been variously described as a wealthy socialite and philanthropist, or as a rich, vain, bad-tempered, money-grubbing skinflint. It depended, I suppose, upon whether or not you owed him money. Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes described him as the perfect Yankee: “He abstained while others indulged, he walked while others rode, he worked while others slept.” Professor Webster did not have as high an opinion of Parkman. Perhaps this is because Professor Webster owed him money. Webster had put up a valuable collection of gems as collateral for a loan from Parkman. Then Parkman discovered that Webster had put up the same collection as collateral for a loan from someone else. Parkman was miffed.

Parkman went to see Webster in his laboratory in the basement of the medical building at Harvard on the afternoon of Friday, November 23, 1849, to demand his money back. “I haven’t got it,” said Webster.

Parkman threatened to have Webster fired. And because Parkman had recently donated the land for the new Harvard Medical School, there was a good chance that he could do as he threatened. In a fit of strong emotion, Webster picked up a hunk of wood and struck Parkman in the head, killing him. He dragged the body to a large sink and, in a much calmer frame of mind, proceeded to dissect it. He put the choice bits in collecting jars and lined them up on a shelf. Fragments of bone and such he burned in his assaying furnace; the larger body parts he tossed down an indoor privy in a corner of his lab.

Parkman’s disappearance did not go unnoticed. It was assumed that he had been abducted, and posters were hung all around Boston. The university offered a $3,000 reward for information as to his whereabouts or the identity of his abductors. Webster went to see Parkman’s brother and volunteered that he might have been the last person to see Parkman alive. He showed the brother a receipt for $483 allegedly signed by Parkman and acknowledging repayment of Webster’s debt.

The following Thursday, Thanksgiving Day, Webster made the mistake of giving the college janitor a turkey. The janitor, Ephraim Littlefield, thought this odd behavior for Webster, who, as far as Littlefield knew, had never given anything to anyone. He had overheard the argument between Webster and Parkman but had left the building before its fatal conclusion. Littlefield decided to investigate the reason for Webster’s sudden munificence and sneaked into the basement lab the next day. The wall of the assay oven felt warm to the touch, but the oven was locked. Littlefield, with his wife standing guard, got a hammer and chisel and broke through the brick wall. In the oven he found bones—a human pelvis and several pieces of leg. He called the college authorities, who in turn summoned the police.

Webster was arrested at his home in Cambridge. “That villain!” he cried, when told of Littlefield’s chiseling. “I am a ruined man!” He attempted to commit suicide in his jail cell by taking strychnine, but he survived.

By the time of the trial Webster had recovered his composure and devised an alibi. The bones, he claimed, were the remains of a cadaver, a medical school specimen he was disposing of.

Then, for the first time in judicial history, forensic anthropology and forensic dentistry were called upon to make the case for the prosecution. Oliver Wendell Holmes, the Parkman Professor and dean of the Medical College, testified that all the various body parts found in Webster’s basement were “consistent” with Parkman’s anatomy. Dr. Nathan Keep, a dental surgeon, testified that the teeth found in the furnace were the lower left portion of a set of teeth he had made for Parkman three years earlier. As it happened, he had kept the mold. When the teeth were compared to the mold, they were a perfect match.

The jury took three hours to find John White Webster guilty of the murder of George Parkman. A few days before his execution six months later, Webster wrote a confession, saying in part:

. . . I was excited to the highest degree of passion; and while he was speaking and gesticulating in the most violent and menacing manner, I seized whatever thing was handiest—it was a stick of wood—and dealt him an instantaneous blow . . . on the side of his head. . . . He fell instantly upon the pavement. There was no second blow. . . . Blood flowed from his mouth and I got a sponge and wiped it away. I got some ammonia and applied it to his nose; but without effect.

The first thing I did . . . was to drag the body into the private room adjoining. There I took off his clothes, and began putting them into the fire which was burning in the upper laboratory. They were all consumed there that afternoon—with papers, pocketbook, or whatever else they may have contained.

My next move was to get the body into the sink which stands in the small private room. . . . There it was entirely dismembered . . . as a work of terrible and desperate necessity. The only instrument used was the knife found by the officers in the tea chest, and which I kept for cutting corks.

The case is notable for two reasons: it was the first time an American court had considered scientific testimony; it was also the first time that a Harvard professor was hanged.

Adolph Louis Luetgert (1845–1899) came to America from Germany in the 18 60s and settled in Chicago. After a series of menial jobs, in 1879 he started his own sausage-manufacturing company. A year earlier his first wife had died, and he had then married Louisa Bricknese, a petite, charming girl ten years his junior. To sanctify the wedding, Luetgert gave his new bride a heavy gold wedding band engraved with the initials “LL.”

According to Luetgert, on May 1, 1897, Louisa went to visit her sister. She never returned. As it turned out, she had never arrived. Luetgert went to the police to report his wife missing. But when she remained away for several more days her brother began to suspect that she was more than merely missing, and that Luetgert might know something about it. The couple had been fighting bitterly for the past few years, so much so that Luetgert had set up a bed in his office at the factory. Rumor had it that Luetgert had been ogling a rich widow.

It occurred to the police that a sausage factory might be the ideal place to dispose of a human body. Indeed, when they searched the building they found a huge vat filled with a caustic solution. They drained the vat and found nothing but four tiny bone fragments and two rings. One of the rings was a thick gold band with the initials “LL” engraved on it.

His wife had visited the factory many times, Luetgert told them. She may have dropped it in the vat by accident.

And the bones?

Sheep bones, pig bones—after all, this was a sausage factory.

Luetgert was tried for murder in August 1897. His defense, combined with reports of sightings of Louisa Luetgert from all around the country, was enough to create a hung jury.

But in January 1898 Luetgert was retried. This time the prosecution called in George A. Dorsey, one of the few expert forensic anthropologists of the time. Dorsey examined the four bone fragments, each smaller than a dime, and declared them to be human. One was the tip of a rib, one a bit of phalanx (toe bone), one a sesamoid bone from the foot, and one the end of a metacarpal (one of the bones that connect the fingers to the wrist).

This time Adolph Luetgert was convicted of the murder of his wife and sentenced to prison for life. Later that year George Dorsey published an important paper, “The Skeleton in Medico-Legal Anatomy,” based on what he had learned while performing research for the trial.

Not everyone agreed with Dorsey’s conclusions. In an unsigned article in the Medical News for March 1899 (“Medical Matters in Chicago”), the correspondent attacked Dorsey’s description of each bone, concluding that “Just as well might one swear to the identity of a coat, when every intrinsic vestige of the garment has disappeared except a button-hole.” But even if the correspondent was right, there was still that damn ring.

On September 7, 1935, Dr. Buck Ruxton, a Parsee who had been born in India in 1899 and educated at Bombay University, accused his “wife” of having an affair with the town clerk. She was Isabella Van Ess, whom he had never gone through the formality of actually marrying. The town was Lancaster. Ruxton had moved to England and gotten a second medical degree from the University of London.

One week later Isabella disappeared along with her maid, Mary Rogerson. The next day, Sunday, September 15, Ruxton told his charwoman, Agnes Oxley, not to bother coming on Monday as his wife was away. On Monday morning he took his children to a friend’s house for the day. On the way home he stopped at the home of Mary Rogerson’s parents and told them that Mary was pregnant. His wife had taken her to Scotland, he said, in order to “get this trouble over.” Everyone who came to the door of his house at 2 Dalton Square seeking medical attention that day was sent away. He was, he said, putting in new carpets. That evening he rented a car, and on Tuesday he was away all day.

Two weeks later, on Sunday, September 29, the mutilated and decomposed bodies of two women were found under a bridge near Moffat, Scotland, 107 miles from Lancaster. The remains were scattered about a ravine known locally as the Devil’s Beef Tub.

The police added up the facts, and on October 13 they arrested Ruxton for the murder of Mary Rogerson. Three weeks later they added the murder of Isabella to the charge. Ruxton called the charges “absolute bunkum, with a capital B.”

Two women were missing under suspicious circumstances, and two bodies had been found. The charwoman told of new stains on the floor and a foul odor in the house when she had come to clean for Ruxton on that Tuesday. A Mrs. Hampshire, who had been hired to clean the staircase, said that the water ran red when she scrubbed the carpet. All very suggestive, but not proof of anything.

The police somehow had to connect Ruxton with two skulls, two torsos, and an assortment of limbs and soft tissue. Various teeth had been pulled from the skulls to make dental records useless for identification. Isabella’s fingertips had been cut off, so that fingerprints could not be used to identify her. Mary Rogerson had never been fingerprinted and so her hands were intact. But the eyes were missing from her skull, so that her pronounced squint would not be in evidence. The tissue had been removed from one pair of legs—Isabella’s legs were noticeably chubby. Isabella had had a bunion on one foot. Indeed, from one of the severed feet where a bunion might have been, a piece of flesh had been removed. Again, this implicated Ruxton but was not proof of anything.

Two forensic experts, Dr. John Glaister of Glasgow and Dr. James Couper Brash of Edinburgh, were called in to see if they could somehow identify the bodies. They managed to pick up a few small details that Ruxton had missed. Mary Rogerson suffered from recurring tonsillitis, and the doctors found microscopic signs of the disease in the tonsils of one corpse. The missing bunion was connected to a deformity in the bones of the severed foot. Missing teeth that had been pulled before death were matched with dental records.

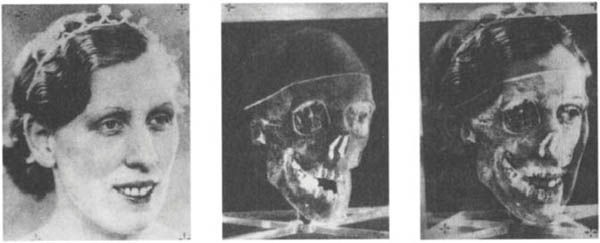

As a clincher, the forensic experts used pictures of the missing women and superimposed them on photographs of the skulls taken at exactly the same angle. The skulls fit inside the photographs exactly. It was a convincing demonstration, and the jury found Dr. Buck Ruxton guilty. On May 21, 1936, he was hanged at Strangeways Jail in Manchester. In 1937 Drs. Glaister and Brash published a book about the case, Medico-Legal Aspects of the Ruxton Case, which detailed both the police work and the scientific investigations. Reviewers were impressed by the extreme care taken by the scientific examiners, and the book helped set standards for future investigations.

In the Ruxton murder case, forensic experts superimposed photos of Isabella Van Ess and the skull of a decomposed body to prove her identity as one of the victims.

The Anthropology Research Facility at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville was founded by Dr. William M. Bass in 1972 when he realized just how little was known about how human bodies decay after death. At the time, Bass was the official state forensic anthropologist, and he did not like being asked questions about human remains that he could not answer. The police often had such questions. Bass got permission to use a two-and-a-half-acre plot of land owned by the University of Tennessee; then he gathered unidentified and unclaimed bodies from the local medical examiners’ offices and distributed them about the property. Some were left out in the open, exposed to the elements and insects, some were buried in shallow graves, some were left in car trunks, and some were partially or completely submerged in water. Records were kept that detailed the progress of each body’s decomposition.

Soon after its founding, the facility acquired the nickname “The Body Farm.” The name stuck. The Body Farm is still in operation and receives about 120 donated bodies every year. In addition to its scientific fact-gathering, police departments use the facility to train personnel in scene-of-the-crime exercises.

There are now body farms at Western Carolina University and Texas State University, and several other institutions are considering opening similar facilities. The study of the defunct human body, though a bit macabre, provides useful information and helps make forensic anthropology a more exact science.

Who saw him die?

“I,” said the fly.

“With my little eye,

I saw him die.”

—“Cock Robin,” English folk song

The earliest-known case of insects helping to solve a crime is the story told by Sung Tz’u, recounted in Chapter One, of blowflies gathering on a peasant’s sickle and thereby indicating that he was a murderer. Except for this one thirteenth-century case, forensic entomology lay dormant until 1855 when Dr. Louis François Etienne Bergeret (1814–1893) performed an autopsy on the mummified remains of a baby. The child’s body had been found behind the mantelpiece of a house near Paris as the house was being remodeled. Bergeret used his knowledge of the life cycle of the insects whose remains he found in the body to conclude that the death had occurred more than five years earlier. He settled on 1848 as the year of the infant’s death, and the young woman who had lived in the house that year was found, arrested, and tried. She was not convicted because it had been impossible to show that the child had not died a natural death. And perhaps it had.

In several cases in the late nineteenth century, the parents of dead babies were spared criminal charges when injuries to the faces and bodies of the children were shown to have been caused postmortem by swarms of roaches.

Entomological knowledge has only recently become systemized enough to be useful in solving crimes. In its life cycle an insect goes through many stages, and each stage may leave behind a telltale trace. Insects can be amazingly precise about where they deposit their eggs, the temperature of their chosen spot, and the time of year or even the day when they lay their eggs. Each species of insect has its own specific rules of conduct about such things.

Two major insect groups, flies and beetles, most commonly colonize corpses, and forensically valuable information can be had from determining the order of their arrival and departure from their hosts.

Each stage in the decomposition of a cadaver is attractive to a different insect. Blowflies (Calliphoridae) and houseflies (Muscidae) are usually the first to arrive at a fresh cadaver, though occasionally flesh flies (Sarcophagidae) will also make an appearance. One or another of these will often show up within minutes of death. The female blowfly will lay her eggs within two days, preferably in a wound, though any body orifice will do. Later come a variety of insects attracted by the changing degrees of decomposition of the corpse or by the insects already there—rove beetles (Staphylinidae) may show up to feed on maggots, for instance. The moldering corpse may attract picture-winged flies (Oititidae), soldier flies (Stratiomyidae), or a variety of others. The last to appear are usually the hide beetles (Dermestidae) and hister beetles (Histeridae). The order in which insects appear is a function of the geographical location of the body and the time of year.

For the first few weeks after death, information as to how long the corpse has been dead and has lain where it was found can be determined from the age and developmental stages of the blowfly maggots in the body. An examination of the pupal cases—the hard shells that are left behind when the insect changes from its final larval stage to its adult form—can provide the investigator with an estimated period of death.

Traces of insects that are not native to the area in which the body was found are an indication that the body has been moved. Insect populations change even over very short distances. The interior of a house or barn will provide a different insect population than the exterior.

Another gift the insect may give the investigator is information about the poisons or drugs to be found in the tissues of the corpse. Any chemicals found in the insect surely came from the corpse it was feeding upon.

Forensic entomologist Dr. Zakaria Erzinclioglu describes a case to which he was called in West Yorkshire, England, in the 1980s. Anthony Samson Perera, a lecturer in oral biology at the dental school of Leeds University, lived with his wife in a house in Wakefield with two small sons and an adopted thirteen-year-old daughter named Nilanthi. The neighbors, who were fond of the daughter, one day realized that they had not seen her for quite a while. This was odd because it was midsummer, not a time for a thirteen-year-old to be spending the entire day indoors. When they asked the Pereras about her, they were told at first that she was indeed inside the house. But Nilanthi remained invisible, and the neighbors notified the social services department that they were worried about her.

The social services people turned the case over to the police, and Detective Inspector Tom Hodgson soon went to call on the Pereras. “The first thing he noticed,” according to Dr. Erzinclioglu, “was that Dr. Perera was an insufferably arrogant man. His manner towards Hodgson and his colleagues was one of condescension, bordering on the ill-mannered.” Perera told Hodgson that the missing girl was an orphan whom they had adopted in Sri Lanka, where they came from. They had brought Nilanthi with them to England so that she could go to school, but the girl was unhappy there and had gone back to Sri Lanka where she was now living with Perera’s mother, Winifred. Perera couldn’t understand why such a fuss was being made over “a simple jungle girl.” And how had Nilanthi been returned to Sri Lanka? Perera had flown with her to Sicily, he said, and had turned her over to his brother, who presumably had taken her to Sri Lanka when next he went home.

Inspector Hodgson checked with the airline; they had no record of Nilanthi’s ever leaving England. He asked Interpol to query the Sri Lankan police. They reported that Mrs. Winifred Perera told them that she had not seen Nilanthi since the girl left for England three years before.

Perera shrugged it off. “Ask my brother,” he said. And where was his brother? He had overstayed his Italian residence permit and had had to leave Italy. Where he was now, Perera didn’t know.

But Perera’s tremendous conceit and his apparent belief in his superior intelligence led him down a dangerous path. He brought some bones into his laboratory, put a few of them into glass jars, and left the others lying about in enamel dishes. One of his colleagues, Frank Ayton, called Inspector Hodgson. Ayton showed Hodgson a coffee jar holding a few small bones, and a five-liter beaker filled with bones floating inside in a green liquid. The two of them searched the laboratory and found a stainless steel tray that held still more human bones.

On the basis of these finds, Inspector Hodgson obtained a warrant to search Perera’s house. The searchers found human remains in three indoor plants and more human bones under the floorboards in the living room. They found yet more human bones and a quantity of long black hair in the garden.

Perera’s unshakable confidence and arrogance did not desert him even in the face of these finds. The human bones were merely biological specimens for his studies, he said. They were under the floorboards to avoid any “misunderstandings” when he had guests. And the bones and rotting flesh in the plant pots were from pork chops used to fertilize the plants. Oh, they were definitely human? Well, they must be from the cadaver he had ordered from Peradeniya University in Sri Lanka.

Despite the glib assurance of his answers, Perera and his wife were placed under arrest. But all this occurred in the days before DNA typing, and the police needed something to tie all those bones together. They bundled everything up and brought it to Dr. Erzinclioglu’s laboratory in Cambridge. They wanted to know if the bones from the garden were connected to the bones in the pots and under the floorboards.

Dr. Erzinclioglu held up the plastic bag holding the bones from under the floorboards. It was teeming with “hundreds of tiny mites belonging to species that are predatory upon other small invertebrate animals in the soil.” But the area under the floorboards was concrete; there was nothing there for the mites to feed on. So the bones must have been brought in from the garden. And there was more. The bones from Perera’s lab held insects that lived in houses, not labs. And some of the larvae were from a species that begins breeding in the spring—around the time that Nilanthi disappeared.

The bones were examined by other experts who concluded that they certainly could be the remains of a thirteen-year-old girl of Asian ancestry. But they could not be more positive than that.

To address the final possibility that Perera was somehow telling the truth—that Nilanthi was alive and well and living with Perera’s mother—Hodgson traveled to Sri Lanka. Nilanthi, it turned out, was not an orphan. But her parents had neither seen nor heard from her since the day she left for England with Perera. And Peradeniya University had never sent Perera a cadaver.

As he sat through the trial, Perera lost none of his arrogance. As he saw it, nothing could be proved against him; it was all supposition and circumstantial evidence. But the weight of the circumstantial evidence proved overwhelming. Nilanthi had certainly come to England with Perera. She was certainly no longer there. She was not in Italy or Sri Lanka. Where was she? The bones in Perera’s house, garden, and laboratory were human. They could have been those of a thirteen-year-old girl. The insect evidence showed they had been put in the ground at the same time that Nilanthi disappeared.

Perera was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. His wife, against whom no evidence had been introduced and who seemed genuinely bewildered by the circumstances, received a suspended sentence and was released.