FORENSIC SCIENTISTS are a group of experts from many fields who share an ability to bend the rigor of science to the needs of justice. Whether they are specialists in pathology, anthropology, psychology, chemistry, or serology, all forensic experts have one thing in common—their willingness and ability to use their specialized knowledge to examine and interpret the evidence of a crime.

Studies have shown that when an expert speaks, juries listen. When one side puts an expert on the stand, the other had better respond with an opposing expert. This has led to a proliferation of “hired guns,” forensic experts who are adept at tailoring their testimony to aid the prosecution or the defense, depending on which side is paying their fee. Experts from state and local forensic labs are, of course, paid out of public funds—their job is to provide information to the police and prosecutors. This inevitably colors their results and their testimony. One of the suggestions of the 2009 report of the National Research Council on “Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States” is that forensic laboratories become as independent as possible by severing their ties with the police and prosecuting attorneys.

Even beyond this systemic bias, the expert system has occasionally gone wrong, and sometimes horribly so. On the basis of “scientific facts” that are neither scientific nor facts, people have been sent to prison, and some have even been sentenced to death.

Junk science is of two types: pseudo-science, in which a body of knowledge is accepted as science and its conclusions acted upon until a major fallacy becomes evident; and valid science that has been misinterpreted, misstated, or misapplied by practitioners who are uninformed or biased.

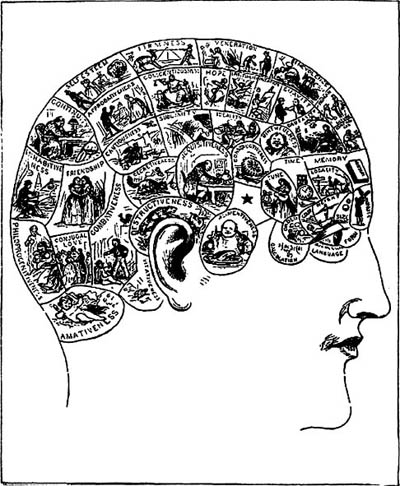

A landmark example of pseudo-science is phrenology, a belief system that was widespread in the nineteenth century. It asserted that one could deduce personality and character traits from the shape and contours of the head, a concept with no scientific foundation whatsoever.

The founder of phrenology was the Viennese doctor Franz Joseph Gall. In 1819 he published The Anatomy and Physiology of the Nervous System in General, and of the Brain in Particular, with Observations upon the Possibility of Ascertaining the Several Intellectual and Moral Dispositions of Man and Animal, by the Configuration of Their Heads. Gall believed that the shape of the head was an indication of the size of the various “organs” (by which he meant structures) of the brain beneath, and that these organs were responsible for the individual’s intellectual and moral capacities. He devised a chart of the head indicating the location of bumps that corresponded to various traits. Among twenty-seven brain organs he identified were intelligence, affection, courage, pride, vanity, guile, benevolence, musicality, a talent for architecture, and the ability to murder.

To this list followers of Gall added gender and racial differences, and whatever else suited their interests. The criminologist Cesare Lombroso found in the precepts of phrenology the ability to predict criminality and to differentiate southern Italians from northern Italians. At the end of the nineteenth century phrenology was used to assess the vocational aptitudes of children, to appraise marriage prospects, and to scrutinize job applicants.

An 1883 phrenology chart of the head, showing its various brain organs.

When Lord William Russell was found murdered in his bedroom on May 6,1840, suspicion focused on François Courvoisier, his newly hired valet. Courvoisier had planted a few diversionary clues in an attempt to suggest that someone had broken in from the outside. Nonetheless he was tried, sentenced to death, and, on July 6, 1840, hanged. A cast was taken of Courvoisier’s head, and Dr. John Elliotson (1791–1868), a founding member of the Phrenological Society and author of Surgical Operations in the Mesmeric State without Pain (1843), studied the cast to see what phrenology might reveal about François Courvoisier. He reported:

In the sides and back and in the posterior portions of the crown reside the dispositions which are as powerful in brutes as in man—love, sexual, parental, and friendly; the disposition to resist, to do violence, to act with cunning, to possess, to construct; self-estimation; love of notice; cautiousness; and firmness.

The organs of the whole of these are very large, with the exception of those of Parental and Friendly Love, which are but mean or ordinary. . . . The part . . . situated just before the organ of the Disposition to do Violence is also very large. . . .

[This] must suggest the most serious reflections to every thinking and humane person upon the improvements necessary in education, in the views and arrangements of society, and in punishments and prison discipline.

A forensic odontologist identifies deceased victims by their dental records. Since the time of the Roman Empire, dentists have been called upon to perform this service. Their services are still in demand today, particularly at scenes of mass violence or large-scale tragedy. Teeth are often the only parts of the body that survive in recognizable form after a fire. As recounted in Chapter 13, it was the survival of Dr. Parkman’s teeth when much of his body was consumed in a furnace that put the noose around the neck of the first Harvard professor to be convicted of murder.

Some forensic odontologists will also attempt to link bite marks left on a victim to the teeth of a particular suspect. The use of this generally unreliable method stems from its successful application in two notorious cases. In 1967 Gordon Hay killed a schoolgirl in Scotland and left a distinctive bite mark (due to malformed teeth) on her left breast. Serial killer Ted Bundy, believed to have killed more than forty women between 1973 and 1978, left bite marks on the left buttock of Lisa Levy, one of his Florida State University victims. Forensic odontologist Dr. Richard Souviron used an acetate overlay of Bundy’s front teeth to demonstrate how they fit exactly over a photograph of the bite marks.

On May 23, 1991, a farmhouse in upstate New York was set afire in order to cover up the murder of its occupant, a social worker. She had been beaten, strangled, bitten, and stabbed to death. Police collected a bloody nightshirt at the scene and swabbed the bite marks for saliva.

They subsequently arrested Roy Brown, a man who had just served a short jail sentence for making threatening phone calls to the director of the social service agency where the victim worked. A year before, this same agency had removed Brown’s daughter from his custody and placed her in residential care. Still, the victim had not been involved in Brown’s case, and there is no evidence that Brown had known her.

Things went rapidly downhill for Brown. A snitch who had met Brown in jail claimed that Brown had called him and confessed to the killing. A local dentist examined the bite marks and concluded that they had been made by Brown’s teeth. At the trial the defense’s expert pointed out that the bite marks showed the imprint of six teeth, whereas Brown was missing two front teeth. The prosecution’s dentist testified that Brown could have twisted the victim’s skin in such a way that the marks would appear to show the two missing teeth. Why he should do this was not discussed. The jury deliberated for five hours before finding Brown guilty.

Brown continued to fight to prove his innocence. When a fire destroyed all his court records, he filed for copies of them under the Freedom of Information Act. Among the documents he received were some that had not been previously disclosed to the defense. These included the report of another prosecution odontologist who had found that the bite marks excluded Brown, and evidence that there was another suspect, Barry Bench, a man with a grudge against the victim. Bench was reported to have been “acting strangely” around the time of the murder. Brown asked for DNA testing on the saliva samples taken from the bite marks but was told that the samples had been used up.

Then, when Brown wrote to Bench and informed him that he would be testing the saliva, Bench promptly committed suicide by stepping in front of a train.

In zoo5 the Innocence Project took on Brown’s case and discovered saliva exemplars on the nightshirt found at the scene. The DNA test showed that they did not come from Brown. Comparison with DNA from Bench’s daughter showed a 50 percent match, exactly what one would expect to find if Bench were the donor.

On Tuesday, January 23, 2007, Roy Brown was released from prison. One month later the district attorney dropped all charges against him.

In 1999 a member of the American Board of Forensic Odontology conducted a study showing that bite-mark evidence was wrong 63 percent of the time. And yet forensic dentists continue to provide sworn testimony that this bite mark was caused by this defendant. And juries continue to take them seriously.

“If you say that this bite fits this person and nobody else in the world, and if you use the bite mark as the only piece of physical evidence linking an attacker to his victim, that’s not science, that’s junk!” says Dr. Richard Souviron, chief forensic odontologist at the Miami-Dade medical examiner’s office. According to Souviron and many other experts, using bite-mark evidence to do anything other than exclude or include a person as one possible donor among many is a miscarriage of justice.

In the section on handwriting of his landmark book Criminal Investigation, Hans Gross writes, “The most important thing an Investigating Officer can extract from a writing is, in every case, the character of an individual.” In this he was completely mistaken. Whether a person is good or bad, sharp or dull, easygoing or driven cannot be reliably assessed from his or her handwriting. It may be possible to judge the age of the writer, but a number of neurological problems can masquerade as the palsy of age.

Although completely innocent of the charges against him, Captain Albert Dreyfus of the French army was convicted of treason in December 1894 on evidence manufactured by the Deuxieme Bureau, the army’s intelligence service, in order to cover up the army’s own ineptitude. Dreyfus was selected for this honor principally because he was a Jew. France, and in particular the French army, was at that time suffering an epidemic of anti-Semitism. After five years on Devil’s Island and another six during which the army knew him to be innocent but refused to admit it, Dreyfus’s conviction was quashed and he was reinstated in the army with the rank of major.

The novelist Emile Zola wrote a now-famous editorial, “J’accuse,” accusing the government of complicity in Dreyfus’s unjust court-martial. Zola was himself prosecuted for defaming the government and sentenced to a year in prison, though the sentence was quickly reversed.

The Dreyfus Affair, as it became known throughout the civilized world, nearly brought down two successive French governments, caused a major shakeup in the army, and engendered a complete loss of faith in the integrity of the intelligence department.

The affair began in September 1894 when Agent Auguste of the Deuxieme Bureau intercepted a letter that had been left at the German embassy for Lieutenant Colonel Maximilien von Schwartzkoppen, the German military attaché:

Having no indication that you wish to see me, I am nevertheless forwarding to you, Sir, several interesting items of information

1. A note on the hydraulic brake of the 120 and the manner in which that part has performed;

2. A note on covering troops (several modifications will be effected by the new plan);

3. A note on a modification of Artillery formations;

4. A note pertaining to Madagascar;

5. The Sketch for a Firing Manual for the country artillery (March 14, 1894).

This last document is extremely difficult to procure and I am able to have it at my disposal for only a very few days. The Ministry of War has distributed a fixed number of copies to the regiments, and the regiments are responsible for them. Every officer holding a copy is to return it after maneuvers. If you would then take from it what interests you and keep it at my disposal thereafter, I will take it. Unless you want me to have it copied in extenso and send you the copy.

I am off to maneuvers.

The letter allowed of no other interpretation than that a high-ranking French officer was spying for the Germans. A copy of the letter was taken to General Auguste Mercier, the minister of war, who took direct and forceful action. “The circle of inquiry is small,” he is reported to have informed his chief of staff, “and is limited to the General Staff. Search. Find.”

The letter, which would become known in France as le bordereau (the memorandum, as though there had never been another), had been torn into six pieces before being reassembled by the section of statistics. This was unusual for material from von Schwartzkoppen’s wastebasket—his usual practice was to tear letters into very small pieces. He later claimed never to have seen the bordereau at all.

The contents of the bordereau were analyzed by Major Hubert Henry of the section of statistics. Because of some of the letter’s references (the new plan and the secret artillery manual), he decided that the writer was indeed an officer with the General Staff, and further that he was an artillery officer.

So the authorities began looking for an artillery officer who had recently been or was still attached to the General Staff. When they went over the list of possibilities, the name of Captain Albert Dreyfus appeared. He was from Alsace, was he not? And Alsace was practically German. And he was a Jew. They found a sample of his handwriting and compared it to that on the bordereau. It was similar! (This would hardy seem surprising—Dreyfus wrote in the same slanting, precise hand that was taught at many schools in those days.)

A handwriting expert, Alfred Gobert, was given the bordereau and samples of Dreyfus’s handwriting. After a long and careful examination, he concluded that the bordereau had not been written by Dreyfus. He was then removed from the case and Alphonse Bertillon, the noted criminologist, was called in. In a matter of hours he concluded that Dreyfus had written the document. To bolster his opinion, two army colonels, Favre and d’Abboville, were made ex tempore graphologists. They too could see clearly that Dreyfus had written the bordereau. Their joint testimony would more than overbalance that of Gobert, who was not even an army officer.

Other evidence against Dreyfus was now assembled, much of it forged. Added to the testimony of Bertillon, who was justly famous for his development of anthropometrics, it would more than suffice. Bertillon was called to testify at Dreyfus’s trial, and his assertion that the handwriting was Dreyfus’s, along with the flamboyant testimony of Major Henry, was damning. Henry capped his testimony by pointing dramatically to a painting of the crucified Christ and declaiming, “I swear to it!” The conviction was unanimous. Dreyfus was sent to the penal colony on Devil’s Island.

Later that year Lieutenant Colonel Georges Picquard, head of the Deuxieme Bureau, was shown an intercepted letter that had been written by Lieutenant Colonel Schwartzkoppen, the German attaché, to Major Ferdinand Esterhazy of the French army. Picquard investigated and had samples of Esterhazy’s handwriting analyzed. The fact was self-evident: it was Esterhazy who had written the bordereau!

When Picquard brought this new information to the attention of his superiors, he was promptly removed as head of the Deuxieme Bureau and sent to a new post in North Africa. Major Henry was installed in his place. To keep the lid on the situation and to keep Dreyfus safely on Devil’s Island, Henry immediately concocted an outrageous forgery. He pasted together parts of a real letter from Schwartzkoppen with his new fabrication, in a manner incriminating to Dreyfus.

In due course, and only because it proved to be unavoidable, Esterhazy was charged with the crime and court-martialed. Picquard was brought back to testify. When Esterhazy was exonerated, Picquard was arrested.

Meanwhile it was becoming increasingly clear to impartial observers that Dreyfus had been unjustly convicted and that, while he suffered on Devil’s Island, the true villain walked the streets of Paris a free and even celebrated man. As more facts were uncovered, the ranks of the Dreyfusards (those who believed in Dreyfus’s innocence), grew. Equally, the regiments of the anti-Dreyfusards swelled and their anti-Semitic hatred of Dreyfus increased. Some high-ranking French army officers were by now aware of their mistake but chose to remain silent. The honor of the French army, indeed of France herself, was at stake—General de Boisdeffre of the General Staff swore that he had seen a document that proved Dreyfus’s guilt.

When Esterhazy was acquitted, Emile Zola felt compelled to protest. In the newspaper L’Aurore, he published the manifesto he entitled “J’Accuse.” It read in part:

I accuse General Billot of having had in his hands definite evidence of the innocence of Dreyfus and of having stifled it, of being guilty of an outrage against humanity and an outrage against justice for a political end and in order to save the compromised General Staff. . . .

I accuse the three handwriting experts [in the Esterhazy trial], Mssrs. Belhomme, Varinard, and Couard, of having composed deceitful and fraudulent reports, unless a medical examination declares them to be stricken with an impairment of vision or judgment. . . .

Finally I accuse the first Court Martial of having violated the law in convicting a defendant on the basis of a document kept secret, and I accuse the second Court Martial of having covered up that illegality on command by committing in turn the juridical crime of knowingly acquitting a guilty man.

The authorities’ response was to arrest Zola and try him for insulting the government. Bertillon was once again called to testify. This time his description of the manner in which the handwriting on the bordereau had been “forged” by Dreyfus showed that he completely lacked credibility.

In order to guide his handwriting, the writer of the bordereau made use of a kind of transparent template inserted at every line beneath the tracing paper of the bordereau. The template consists of a double chain: the first chain is composed by the word “intérêt” traced end to end indefinitely and meshing with each other; that is written in such a manner that the initial I merges with the final t preceding it; the second chain is identical to the first, but displaced 1.25 mm. To the left.

The transparent template is traced from the word intérêt, which concludes a letter found in Dreyfus’s blotter. The word itself is not written naturally, but constructed geometrically.

Zola was found guilty and sentenced to a year in prison. He contemplated serving the term as an expression of his contempt for the current government, but his editors convinced him that freedom was the better part of valor. He fled to London.

On August 13, as he carefully examined all the documents in the case at the direction of the minister of war, Captain Louis Cuignet made an astounding discovery. The letter that Major Henry had “found” was pasted together from two different paper stocks. The thin, colored lines that ran through the two types of paper did not match. Not only that, but the lines were of entirely different colors. It was clear that Henry had forged the document.

General de Boisdeffre, who had sworn in public to the authenticity of the document, promptly resigned. Esterhazy was discharged from the army. Henry was taken to prison for further questioning. The next day, while left alone in his cell, he slit his throat with a straight razor.

In 1899, on the basis of the new evidence and the changed circumstances, Alfred Dreyfus was returned to France from Devil’s Island to stand trial once again for treason. And once again he was found guilty.

The President of France, deciding that enough was enough, granted Dreyfus a pardon. But still he was not vindicated. In 1904 the court of appeal agreed to rehear the case, and in 1906 the conviction was thrown out. Dreyfus was reinstated in the army as a captain. He retired in 1907 but was called up for service again during World War I.

On March 1, 1932, the infant son of aviation hero Charles Lindbergh was kidnapped from the Lindberghs’ home in East Amwell, New Jersey. The kidnapper left behind a ransom note:

Dear Sir!

Have 50.000$ redy 25.000$ in 20$ bills 15000$ in 10$ bills and 10.000$ in 5$ bills. After 2–4 days we will inform you were to deliver the mony.

The ransom note from the Lindbergh kidnapping. Experts agreed it had probably been written by a semi-literate German immigrant.

We warn you for making anyding public or for notify the polise the child is in gut care.

Indication for all letters are singnature and 3 holes.

In the bottom right-hand corner of the note was the “singnature”—a pair of inch-wide, interlocking blue circles with the overlapping space colored red. In it, there were three holes that might have been pushed through with a pencil. More letters followed, all similarly misspelled, and all marked with the same identifying symbol.

The letters were given to several experts for analysis. On the basis of the misspellings and the phraseology in the letters, the experts agreed that the writer was in all probability a semi-literate German immigrant. Handwriting analyst Albert S. Osborn contrived a paragraph that the police might place before a suspect and ask him to copy. It contained several of the words that the kidnapper had misspelled, such as money (mony).

The ransom was paid, but the child was not returned. A few weeks later the severely decomposed body of a small child was found in the woods about four miles from the Lindbergh house.

In 1934 a man with a German accent stopped at a gas station and bought 98 cents’ worth of gas, paying for it with a ten-dollar gold certificate. Gold certificates, which were paper bills directly backed by gold, had been withdrawn from circulation in 1933. The attendant, fearing that the bill might be counterfeit, noted the license plate of the car. The certificate turned out to be from the Lindbergh ransom. The car belonged to Bruno Richard Hauptmann.

Hauptmann was asked to provide samples of his handwriting. Albert Osborn and his son, Albert D. Osborn, compared these samples with the writing on the ransom notes. To the Osborns they did not look similar. The police instructed Hauptmann to write more notes, telling him just how to spell certain words. These too were not close enough to convince the Osborns. There were too many dissimilarities between Hauptmann’s writing and that of the ransom notes, and to many discrepancies among the writing samples themselves.

When a search of Hauptmann’s garage turned up more than $14,000 in additional ransom money, he was arrested. He claimed that Isador Fisch, a friend who had returned to Germany, had left the package of money with him. He was not believed. And the discovery of the money convinced the Osborns that the writing on the ransom letters was Hauptmann’s after all.

Eighteen months later at Hauptmann’s trial the ransom notes were introduced into evidence along with the samples of Hauptmann’s writing. No one bothered to tell the jury that Hauptmann had actually been given the notes to copy from, and had been made to practice for hours until his handwriting matched that on the notes.

The handwriting exemplars and the ladder that had been used in the kidnapping were the primary pieces of evidence against Hauptmann. The state maintained that it had proved that the ladder had been made from lumber in Hauptmann’s garage. Today there are people who feel that the ladder evidence was at best exaggerated.

Hauptmann was executed in New Jersey’s electric chair on April 30, 1936.

As chief of serology at the West Virginia State Police Crime Laboratory from 1980 to 1989, Fred Zain testified as an expert witness in hundreds of criminal cases. His manner on the stand was imposing and his command of facts impressive—when he testified for the prosecution, the prosecution tended to win. He resigned in 1989 to take a more lucrative job as chief of physical evidence for the medical examiner in Bexar County, Texas.

Although it would not catch up with him for a few years, Zain’s downfall began in 1987 when he testified at the rape trial of Glen Woodall. According to Zain, analysis of the semen found at the rape scene showed that “[t]he assailant’s blood types . . . were identical to Mr. Woodall’s.” Woodall was convicted and sentenced to serve between 203 and 335 years in prison. Five years later, when Woodall and his attorney were finally able to get DNA testing of the semen, it was shown conclusively not to be his. Woodall sued West Virginia for false imprisonment and settled for $1 million. When the West Virginia Supreme Court decided to look into Zain’s testimony, it asked retired circuit judge James O. Holliday to conduct an investigation of Zain’s tenure with the West Virginia Crime Laboratory.

Five months later Holliday issued a report in which he concluded that throughout his tenure at the lab, Fred Zain had been consistently guilty of:

[1] Overstating the strength of results; [2] overstating the frequency of genetic matches on individual pieces of evidence; [3] misreporting the frequency of matches on multiple pieces of evidence; [4] reporting that multiple items had been tested, when only a single item had been tested; [5] reporting inconclusive results as conclusive; [6] repeatedly altering laboratory records; [7] grouping results to create the erroneous impression that genetic markers had been obtained from all samples tested; [8] failing to report conflicting results; [9] implying a match with a suspect when testing supported only a match with the victim; and [10] reporting scientifically impossible or improbable results.

Trooper Zain’s misconduct thus significantly tainted his testimony in numerous criminal prosecutions. In this regard, the Holliday report stated: “It is believed that, as a matter of law, any testimonial or documentary evidence offered by Zain at any time in any criminal prosecution should be deemed invalid, unreliable, and inadmissible in determining whether to award a new trial in any subsequent habeas corpus proceeding.”

Kenneth Blake, who had been director of the West Virginia State Police’s Criminal Identification Bureau, was later asked about the complaints that had been lodged against Zain by others at the lab, in which they alleged that he had filed false reports. At the time, Blake had dismissed the allegations as an office squabble. “They didn’t like Zain, and Zain didn’t like them,” Blake had explained. “But we never had any complaints from prosecutors, defense attorneys, or investigators.”

In 1995 Baltimore police sergeant James A. Kulbicki was found guilty of the first-degree murder of twenty-two-year-old Gina Marie Neuslein and sentenced to what criminal attorneys call LWOP—life in prison without the possibility of parole. Twelve years later the so-called scientific evidence that formed the basis of his conviction had fallen to pieces.

Neuslein had been having an affair with Kulbicki, a married man, and had just had his child. She was planning to sue him for child support. Joseph Kopera, Maryland’s top firearms expert, testified that Kulbicki’s gun had been recently cleaned and that the murder bullet was “consistent in size” with the ones used by Kulbicki’s gun. An FBI expert testified further that the lead fragments found in the victim—all that remained of the murder bullet after it entered Gina Neuslein’s skull—were identical in composition with the lead in Kulbicki’s bullets. Against this expert testimony were defense witnesses who had seen Kulbicki running errands at the time of the murder. They were not believed.

Then, in 2005 the FBI announced that it would no longer do bullet lead analysis, as the conclusions reached by that technique were unreliable. And in 2007 Maryland state public defenders, working with the Innocence Project, discovered that ballistics expert Joseph Kopera had lied about his credentials, falsely claiming degrees from two universities and forging at least one document to back up his claim. The day after this discovery, Kopera committed suicide.

When they examined the notes that Kopera had made when he tested Kulbicki’s gun, investigators found that they flatly contradicted the testimony he had given. He had found in fact that Kulbicki’s gun could not have fired the bullet that killed Neuslein.

“If this could happen to my client, who was a cop who worked within the justice system, what does it say about defendants who know far less about the process and may have far fewer resources to uncover evidence of their innocence that may have been withheld by the prosecution or their scientific experts?” asked Kulbicki’s attorney, Suzanne K. Drouet, a former Justice Department lawyer.

At this time Kulbicki’s request for a new trial is still pending. No doubt most forensic analysts are honest, dedicated, and competent, follow the evidence impartially, and do not manipulate it to suit their own biases. Those misguided few who knowingly doctor the evidence honestly believe they are doing it in a good cause—helping the prosecution put away a “bad guy.”

Even when we add these to the incompetent, we still have a very small number of criminalists who taint the profession. But these few can do great damage to the criminal justice system.

To address this problem the National Research Institute suggests that all forensic science professionals be certified, with standards for certification established by the National Institute of Forensic Science based on the recognized standards for each discipline. It recommends further that “No person (public or private) should be allowed to practice in a forensic science discipline or testify as a forensic science professional without certification.”

This will help eliminate those with fraudulent credentials, and rigorous testing and recertification every few years will keep the true professionals up to date.

Forensic evidence, properly analyzed, is more reliable than eyewitness testimony, more reliable than the testimony of supposed accomplices, more reliable even than the freely given confession of a suspect. With each passing decade, more scientific techniques become available to the forensic technician. These should be made available to the prosecution and the defense alike. Further, all physical evidence should be carefully preserved in the event that tests we cannot now even imagine may become available in the future to affirm or refute the decisions of today’s courts. The judicial doctrine of finality should not be applied to those on death row or to those spending the rest of their lives behind bars.