Sixty plus? Time to get moving

Muir Gray

You are 60 plus – you’re at a good time of life – some would say in the prime of life. Surveys have shown that people aged 70 to 74 report the best feelings about life. People in their 60s face more pressures. Many are still supporting their parents, often far away, and still have children dependent on them. They are part of the sandwich generation. People in their 70s rarely have worries about elderly parents, but often still worry about their children and sometimes the chicks return to the nest. Some people, of course, have to cope with the disability or death of a partner, but it is a good time for most people in their 70s.

For people in their 80s life is tougher, with health problems playing a bigger part, but the image of life from 60 onwards being dominated by disease, disability, dependency and dementia is wrong. OK, so you may be a bit slower than you were because of a dodgy hip, you may be a bit more forgetful or you may have a more serious condition, such as arthritis or diabetes, but it is important to remember that people in their 60s, 70s and 80s are a key group in society. For one thing, if they gave up caring for other people the NHS would collapse, tomorrow.

Of course, life could be better; and many people over 60 would benefit from a higher income. Unfortunately, poverty is still too common a problem in old age but that’s true for almost everyone, not just people in their 60s, and anyway that’s not what this book is about. This book is about giving you the good news, that life can get better without a windfall from the Lottery. Diana Moran and I are both in our 70s, and we’ve spent our lives studying, preventing and even evangelising about the benefits of exercise and the good it can do for us.

Whatever your age or your income, whether or not you have one or more long-term conditions, and five or ten prescriptions, becoming more active and taking more exercise will:

• Help you feel better

• Reduce your risk of many common health problems, such as heart disease, stroke, depression and, best news of all, dementia

• Make the treatment for any condition or disease more effective, and can sometimes lead to the need for pills disappearing completely

• Improve both your mood and your brain function – how you think and feel

Fantastic, but why isn’t exercise available on the NHS, like pills and X-rays? Well, it’s not yet, but it is coming because the medical profession is finally waking up to the potential benefits of exercise. Of course, you need to do other things to feel better and stay well, to live longer and aim for a good death as well as a good life, but this book is your guide to exercise – the miracle cure. About half of people aged 60 plus have one or more than one condition, so at your next appointment ask your GP or the hospital doctor you see about whether exercise will help you deal with your particular condition. The answer will almost always be ‘yes’. I suggest looking at the NHS Choices website: www.nhs.uk. Type in the name of your condition and, whether it is diabetes or depression, somewhere in that excellent web knowledge service you will find encouragement to be more active.

What’s your plan?

The first thing you should do is reflect on where you are in life and where you would prefer to finish up.

One of the myths about older people is that they live in the past. Of course, this is not true. However, the evidence suggests that, with the exception of financial matters, not enough older people think ahead. OK, so if you have children, you quickly work out how to leave as much to the family as you can without incurring the wrath of inheritance tax. But what about planning your future health and well-being, including how you prefer to die, or, even more important, how you hope not to die?

Take a moment to reflect on the following question: How would you prefer to meet your end?

Would you like to:

1. Pop off without warning?

2. Spend the last months, or even years, unable to dress or get to the toilet without help?

3. Stay fit and independent, then have a short final illness?

Why not pause and discuss the options with someone who will be affected by your death? How did you rank the options? The prospect of months or years of immobility and dependence would be at the bottom of everyone’s list, and many people like the idea of popping off without warning, preferably on the way home from the perfect holiday on which you had spent the last of your money! However, sudden death leaves many unhappy people behind. There are bereaved family members who never had the chance to tell the person who died how much they loved them and was helped by them, or heard that person say ‘I love you’ or ‘I forgive you’. The best of the three ways of dying is the short final illness, which gives everyone the chance to say their goodbyes.

Towards the end of the 20th century there was growing concern that the recommended strategy of risk reduction, including avoiding physical activity, was just keeping people alive to a miserable advanced old age, condemning those in their 90s to years of disability and dependence. However, recent research points firmly in a completely different direction. Increasing the frequency and intensity of exercise will not only reduce the risk of an early death; it will also:

• Keep you fitter for longer and reduce the time you will be dependent on others

• Help you feel better next month, and every month after that

So, let’s get moving more, now. But you know this already don’t you? It is obvious, so why are you now taking less exercise than you did when you were 20, or less exercise than you know, or think, will transform your health? Here are the most common reasons people give for not exercising enough, and our solutions to the problem.

Your good reason: I don’t have the time

Our response: We understand that but you owe it to yourself to manage your time better so as to give a little bit more to yourself. Just ten minutes every morning will give you enough time for our Triple S, Strength Skill and Suppleness programme. And ten more minutes focused on brisk walking, once, or better still, twice, or (best) three times a day for the fourth S – stamina.

Your good reason: I can’t afford it

Our response: Although we recommend weights and resistance bands or classes in techniques such as Pilates, these are optional extras – good ideas for birthday presents. The exercises can be done without spending money, or by using a big bag of flour or sugar as a weight (the best thing to do with a bag of sugar!).

Your good reason: I have not enjoyed exercise in the past

Our response: We will help you understand the benefits. You are not doing physical activity because it is fun (although it can be). Think of it as training for the decades to come. Athletes train for the Olympics; you are in training for your eighties and that will be a big event. We also recommend you do it with a buddy or two. Even when doing your daily dozen on your own at home, find some other friends to do it at the same time. They will feel the same as you; be a bit supportive and a bit competitive.

Your good reason: I am too busy helping other people

Our response: We know how much people in our age group do for grandchildren, children, parents, partners, neighbours and the community, but they need you to look after yourself too. In addition, it will help your children and grandchildren considerably if you are still active and independent in your eighties, so getting fitter is part of looking after those you love and care for.

Healthcare is what people do for themselves, and one of the best types of healthcare is to get moving!

Now, the first step is not to get up out of your chair and go for a walk, although it is good to stand and stretch if you have been sitting down for 15 minutes or more. The first step is to understand what is going on inside your body as the years pass. In times past, growing older was seen and often portrayed in pictures as a time of increasing inactivity, of sitting dozing by the fireside. But what we now know now has led to the development of a new approach based on new facts about ageing and activity.

The new facts of life – the birds and the bees – for people over 60

The new facts of life are:

• First, that physical activity is more important for people in their 60s, 70s, 80s, 90s and beyond than it is for people in their 20s and 30s

• Second, that it is at least as important to try to increase fitness after the onset of disease as it is to try to prevent disease through increased activity

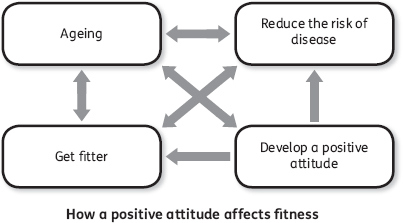

This is nothing short of a revolution in how we think about growing older, and that revolution has to be led by older people. The most important fact to understand is that ageing is not the cause of all the problems that are more common in older adults. Until the age of 90 the biological process of ageing has little effect on your ability to look after yourself, engage with other people or get about independently. If you reach the age of 90 and are affected only by ageing you will be independent and active, and even in work, like Her Majesty The Queen or David Attenborough, for example. Some decline in ability is inevitable but the rate at which our abilities decline is influenced not only by ageing but also by three other processes which do cause problems – disease, loss of fitness and a negative attitude to life – and all three are interrelated.

The most important of these processes is what you believe and your attitude to life.

Strengthening and keeping your positive attitude

A pessimistic attitude and outlook on life is influenced by the negative, and incorrect, portrayal of ‘old age’ as a period of inevitable and irreversible decline by most media. A pessimistic attitude does accelerate the rate of the decline however, partly because people who adopt this attitude make no attempt to get fitter, let alone keep fit, nor do they try to reduce the risk of disease.

Some people, unfortunately including some doctors, say ‘It’s your age’ or, even worse, ‘what else do you expect at your age?’ These statements are examples of ageism, and although we have heard less about ageism than racism or sexism, it is moving up the agenda. Ageism is a prejudice and a prejudice comes from the term ‘prejudging’, namely judging someone on the basis of one characteristic before you know what they’re really like.

The first point to make is that people who are 60 or 70, or any age for that matter, differ from one another in many ways, so all generalisations have to be taken with a very big pinch of salt. The second point is that such statements are based on the false belief that all problems are due to the ageing process. This belief is widespread and influences many people, including many older people.

So, always remember that you are you; never mind whatever other people think. You need to believe in yourself and in these magnificent seven facts:

1. Ageing by itself is not a major cause of disability itself until the 90s

2. Many of the problems that we have assumed are due to ageing are due to loss of fitness

3. Many of the problems that we have assumed are due to ageing are due to preventable disease

4. The risk of disease can still be reduced after the age of 60

5. Fitness can be regained after the age of 60

6. The problems of too many older people are caused by deprivation and poverty, not ageing

7. People who are over 60 make a positive contribution to society in many ways; for example, without the contribution of people in their 60s, 70s, 80s and older the NHS would collapse tomorrow

• It is important to be clear in your own mind about the factors that influence your abilities

• It is important not to feel guilty about the problems of younger people

• It is important to be positive and optimistic.

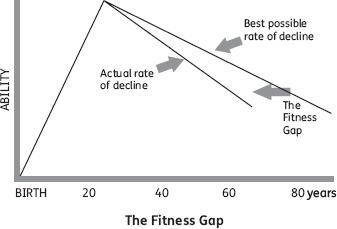

The fitness gap and how to close it

‘What has fitness got to do with me?’ I hear you say. Well, there are two answers to that. First, physical activity is a good antidote to depression and it increases the probability that you will feel well in the short term (as well as making your muscles and heart work better). However, getting more active is also an insurance programme for the long term. This insures you against the risk of becoming incontinent, dependent on other people, and becoming a burden to your nearest and dearest – possibly the biggest fear of all!

The good news is that whatever your age you can close the fitness gap between the best possible rate of decline, which only a few very fit people follow, and the actual rate of decline.

There has been little or no research into fitness for centenarians, but the anecdotal evidence is persuasive. Many of those who have made it to three figures are certain that they have reached the milestone by keeping themselves active. There are, however, some studies of people in their 90s and very many studies of people in their 80s, 70s and 60s, all of which have the same very encouraging message – whatever your age, you can get fitter and improve your level of ability, as shown in the figure below.

The scientific evidence about the benefits of training is very strong, and has been for decades. Twenty years ago Professor Roy J. Shephard published his classic book Ageing, Physical Activity and Health. His message is clear and unequivocal – by becoming more active ‘biological age is effectively reduced by as much as 10 to 20 years.’

There are four aspects to fitness, all of which can be improved:

1. Stamina: how long you can keep going

2. Skill: how well you can co-ordinate your actions, for example when recovering from a stumble

3. Suppleness: the opposite of stiffness

4. Strength: what your muscles can do (and power: how quickly they can do it)

Getting fitter and keeping fit are high priorities and the new message from research is that getting fitter may be even more important for people with one or more than one disease or condition than it is for people who have managed to avoid developing any condition.

Getting fitter is both a means of prevention and a type of treatment.

Disease: reducing the risk and coping with it

Disease occurs more often in older age groups, and although some of these diseases are related to the ageing process, most of them are due to a different cause: having lived for a long time. This is not the same thing.

The more years you live with a bad diet or in an unhealthy environment the greater the likelihood that you will develop a disease. But this is not a result of ageing.

The wake-up call for many people is the diagnosis of high blood pressure or Type 2 diabetes or any of the other modern epidemics. This is the kick in the pants that they need. Sixty per cent of people aged 60 have a condition such as this, as do more than 70 per cent of people aged 70 and above. And, as the decades go by, the percentage of people having more than one condition increases. But what do we mean by ‘conditions’ and how do they relate to disease?

Once upon a time diseases were pretty clear-cut. You either had tuberculosis or a broken leg or you didn’t. However, medicine has changed over the years as the population has aged. Now we use the word ‘condition’ to mean a state in which your health is impaired or you are at risk of some serious complication, even though you didn’t know you had it until a doctor or nurse told you.

High blood pressure is an example of a condition; so too is Type 2 diabetes. By this we mean that there is not a sharp cut-off point between people with the condition and people without it. Identifying high blood pressure as a problem comes through measuring your blood pressure. But doctors and nurses have arbitrary limits about the level of blood pressure. So, when they say, ‘You have got high blood pressure, I’m afraid,’ what they should really say is, ‘Your level of blood pressure is such that there is an increased risk of stroke and dementia. I recommend you consider taking medication to reduce it. Although I have to warn you that the medication itself has side effects. And although you have not noticed this increase in your blood pressure, you may well notice the effects of taking the medicine that I could prescribe to bring it down.’

An even better response from the doctor might be: ‘Your blood pressure is not dangerously high, so before I offer you drug treatment, I would like to suggest you start a fitness programme. Physical activity combined with associated weight loss might bring your blood pressure down and avoid the need for drug treatment.’

This is, of course, quite a long rigmarole but it is something that doctors are increasingly saying to people. Many conditions of modern life are caused by the environment. This environment leads to inactivity, which in turn leads to the steady increase in weight that so many people experience from the age of 20 onwards.

While it is important to understand the distinction between a condition and a disease, there are, of course, diseases that are still quite distinct and different – rheumatoid arthritis, for example, or parkinson’s. But the simple fact is that we need to be thinking about fitness for both conditions and diseases. Even if these diseases reduce your ability to move and make it more difficult to take exercise, the scientific evidence is now clear that increasing physical activity is essential, and never more so than after the onset of a condition or disease. Sometimes, exercise is at least as important as the medical treatment itself.

Some diseases, such as arthritis, do reduce your ability to exercise, as shown in the figure below. But we also find that people lose fitness more quickly after the onset of their condition or disease than before it.

After all the good news, it is still the case that too many people are simply given pills when a condition or a disease is diagnosed. Not enough are given pills plus advice on exercise. The medical profession is waking up to this and recently the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges published a major report called ‘Exercise – the Miracle Cure’. Yet, despite this, the focus is still on pills and operations in too many consultations, at too many health centres and too many hospital clinics.

On top of this, well-intentioned relatives can add to the problem through their efforts to help. ‘Don’t you worry about the shopping, dear, I’ll do that for you. You don’t want to walk to the shops when it might rain.’ The new facts of life are that walking to the shops, as briskly as you can, is even more important if you have a long-term condition than if you don’t.

If you are living with a long-term health condition and are looking to use exercise as therapy, there’s lots of great advice on the big common problems online from the following organisations:

Diabetes UK

Asthma UK

The British Heart Foundation

The Stroke Association Arthritis Research UK

Parkinson’s UK

Macmillan Cancer Support The Alzheimer’s Society

The Lung Foundation

Rethink Mental Illness

MIND

The MS Society

UKActive, the new charity promoting activity, has identified people who are ageing as a priority group and all the key professional groups like the British Geriatrics Society and the Chartered Society of Physiotherapists are now promoting physical activity among older people with health problems. In addition, The Centre for Ageing Better has identified inactivity as a priority and AgeUK does wonderful work. It stimulates many people through their local programmes called Inspire & Include and Get Going Together.

Get moving to better health and slower ageing

So a new approach is needed. Vast sums of money are being spent on the search for the elixir of life, a drug that would slow the ageing process. As yet, there is no such thing. But there is a fascinating new idea emerging from research, namely that by becoming more active we can reduce a biological change that seems to be one of the main causes of what we call the ageing process – inflammation.

We all know about acute inflammation: the swollen, red tenderness round an infected cut. The inflammation of tissue; a characteristic of ageing, has been assumed to be due to the normal ageing process, about which nothing could be done. However, recent studies show that inflammation of key tissues, blood vessels and the brain, for example, can be prevented – and the main means of prevention is, you guessed it, activity.

To understand why getting moving can prevent ageing we need to look at the stress reaction. This is sometimes called the ‘fight or flight’ reaction. When we were evolving as human beings, life was full of sudden dangers. Our ancestors would always need to be ready to react to an encounter with a sabre-toothed tiger or a hostile neighbouring tribe, for example. The stress reaction then was very helpful, helping you to either take flight and run away quickly, or fight.

Nowadays, such threats are uncommon, but we still have stress in our lives, though today it is often experienced in a situation in which you cannot fight or take flight. And we now know that if you experience stress when you are physically inactive the result is an inflammatory reaction. If, for example, there is a family quarrel or a complaint from a neighbour, and you have to cope with the stress while sitting and inactive, the result is inflammation.

Stress + inactivity = inflammation

The antidote to ageing

The ageing process cannot, as yet, be slowed down. But by focusing on the three other aspects of growing older – loss of fitness, disease and attitude – you can stay young and even feel younger.

Common to all three of these processes is the need to increase activity.

What’s going on inside you

‘This baby could live to be 142 years old’ was the startling caption for a photo of a baby on the cover of Time magazine at the end of February 2015. It was a special edition based on ‘Dispatches from the Frontiers of Longevity’ which contained ‘new data on how to live a longer, happier life’.

Perhaps the most important fact is that ageing is not the cause of all the problems that are more common in older adults. There is no doubt that ageing exists as a normal biological process. It starts in the early 20s – as our phase of growth and development comes to an end. The general effect reduces our ability to cope with challenges, such as infection and loss of balance, as well as the biggest challenge of the 21st century – inactivity.

Keeping above the line

During their phase of development our children are dependent on us. Now, that phase of dependence seems, to many parents at least, to be increasing, as the rising cost of housing forces an increasing proportion of young people to stay in the family nest for longer. However, unlike small children, at least our grown up children are able to dress themselves, clean their teeth, get to the toilet in time and feed themselves (even if they can’t yet do their laundry!). They are above the line – the dreaded line that marks our level of ability. When we fall below the line we then become increasingly and depressingly dependent on other people.

The importance of fitness is that it can determine when you drop below the line or whether or not you drop below it at all, as shown in the figure above. This poor person dropped below the line at which they could reach the toilet in time at the age of 78. This wasn’t because of the ageing process but because they had not maintained their level of fitness. Of course, there are often other factors, such as the environment in which you live. If your toilet is up a flight of stairs, then the challenge comes sooner than if you have a toilet on the ground floor; the line is a little bit higher but the same principle applies. It is not ageing that determines when you cross the line, or indeed whether you will cross the line at all, it is ageing plus your level of fitness. But never forget, the good news is that your level of fitness, and therefore your level of ability, can be improved at any age.

Caring through activity

Millions of people over 60 care for others who are severely affected by disease and disability. In addition, there are many people in care homes because they have been unable to continue coping on their own.

The word ‘care’ is an important one. Obviously one aspect of the term is something we would all welcome, namely compassion and sympathy. However, caring for someone all too often means doing things for someone, usually with the best of intentions, in order to help them, but often because it is quicker to do so. If you care for someone you should help them to become more active and more independent, and there are a number of ways in which this can be done. Diana Moran has compiled a detailed range of exercises that will be perfect for your needs whatever they are. Read on.