1962-1963

WHEN HAROLD MACMILLAN VISITED OTTAWA IN APRIL 1961 AFTER his first meeting with President Kennedy, he left Diefenbaker with a fresh anxiety. Macmillan reported that Kennedy would welcome British association with the European Economic Community, which then included the six nations of France, West Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Italy. Britain’s efforts to organize the European Free Trade Area, or “outer seven” – among itself and Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Austria, Switzerland, and Portugal – had failed to produce substantial benefits, while the Common Market of “the six,” under French and German leadership, was beginning to demonstrate its potential. The community, it appeared, would become a formidable economic and political force, inspired by the vision of Franco-German reconciliation, the ancient memory of a single Europe, and the challenge of resistance against the communist threat from eastern Europe. By the spring of 1961 Macmillan had decided that Britain and the seven (or perhaps Britain alone) should seek closer ties with the community; and now Kennedy had urged him on.1

For both George Drew and John Diefenbaker, this was a shock that hinted at British betrayal. Diefenbaker had invested his political capital in promoting Canada’s ties with Britain and the Commonwealth. A new British commitment to Europe, he feared, would have both symbolic and practical effects, relegating the Commonwealth to the background and possibly threatening Canada’s preferential access to the United Kingdom market. Canada’s delicate effort to balance its economic dependence on the United States would be upset, and Britain would be seen to rebuke the sentimental commitments of the Canadian Tory leader and his party. That signal of British indifference might be particularly damaging during the coming general election campaign. From June 1961 onwards the Diefenbaker government engaged in a frantic effort to discover Britain’s intentions, to protect what it saw as Canada’s interests, to dissuade Britain from its goal, and then – uncertainly – to subvert the formal British application for admission to the community.

The confused nature of the Canadian campaign was a product of Diefenbaker’s unreconciled emotions: his genuine affection for the United Kingdom, his sense of hurt and his desire to show it, his vague fear of economic injury, and his simultaneous unwillingness to accept criticism for his stance. It was also (and not by chance) an echo of Lord Beaverbrook’s campaign in the pages of his Daily Express against British entry into Europe. Drew and Beaverbrook shared their views on the subject, and Drew provided Diefenbaker with frequent reports from the Daily Express. As the Beaver ranted in London, Diefenbaker seemed little more than his colonial sales agent, hawking the same old imperial dream from British North America. The Canadian government’s campaign was controversial from the beginning, and especially upsetting to the old core of Conservative supporters because it publicly criticized Great Britain. It was disturbing also to others – including many businessmen and the Liberal opposition – who felt that obstruction would undermine rather than benefit Canada’s political and commercial links with the United Kingdom.2

When Macmillan decided to send the secretary of state for commonwealth relations, Duncan Sandys, to meet Commonwealth heads of government individually to discuss Britain’s interest in Europe, Diefenbaker protested that Sandys was the wrong person, that a meeting of Commonwealth prime ministers should be convened instead, and that France, in any case, would not agree to Britain’s terms. “I told him that I had seen a report re France to the effect that France was continuing to insist that joining the Common Market must be on the basis of the full acceptance of the Rome Treaty, and that during the discussions that the United Kingdom Government had made it clear that it did not intend by joining to abrogate the trade and industrial products from Canada, nor Agricultural products from Canada, Australia and New Zealand.”3 Diefenbaker insisted that he did not object in principle to British entry, but press reports suggested that his purpose in calling for a full meeting of prime ministers was “to form a common front to protect Commonwealth trade interests in [the] British market.” Failing that, a proposed conference of Commonwealth finance ministers in September 1961 seemed to be the first occasion for a collective response.4

In preparation for Sandys’s visit to Ottawa, Macmillan assured Diefenbaker on July 3 that “the decision we have to take now is not whether to join the Common Market, but whether to open negotiations with a view to finding out what special arrangements would be obtainable. Previously we had hoped to avoid entering negotiations unless there was a high prospect of success. But since it is not possible to clarify the position in advance, we feel that the risk of a breakdown might have to be accepted.” That seemed partly intended as reassurance to other Commonwealth countries that Britain would go into negotiations determined to protect their trading interests, and to accept rejection if it could not do so.5 Macmillan explained that Sandys would discuss “how best to organise a system of close and continuous Commonwealth consultation to cover the period of preparations for negotiations, the negotiations themselves, and the eventual decision… whether or not to join the EEC.”6

Diefenbaker and Drew were convinced that the Macmillan government had already made a decision in favour of entry, and that all this reassurance might be a trick. Open protest was thus a legitimate means of forcing a British retreat. But Norman Robertson and Robert Bryce were disturbed by the signs of public conflict, and argued for a return to quiet diplomacy. Bryce advised Diefenbaker that he should express Canada’s apprehensions “without making any statement either to Sandys or in public that could be used to blame Canada for upsetting a move that is now the evident desire of the UK Parliament and public, as well as the UK government.” Instead, he should argue privately that the United Kingdom had little bargaining strength against the six, and that if Commonwealth trade could not be protected, the association would be seriously damaged “at the very time that it appears likely to prove the most valuable in helping to bridge the widening gap between the white peoples and coloured peoples.” The Commonwealth, then, was worth more to British power and prestige than membership in the community; the United Kingdom should recognize that and draw back.7

The prime minister let Howard Green, George Hees, Donald Fleming, and Alvin Hamilton take the lead in meetings with Duncan Sandys on July 14; but he met with Sandys as well, and added his own gruff message of opposition. He believed that the Commonwealth would be damaged: “that was my feeling and it might be emotional as I had a deep attachment to the Commonwealth.” If the United Kingdom joined the market, Diefenbaker said, “Canada and Australia would be driven into closer relations with the United States.” He suggested that the United States was trying to “push” the United Kingdom into the Common Market (a description of American methods that had particular meaning for Diefenbaker since he had acquired the Rostow memorandum in May), but Sandys denied it. The joint communiqué after the meetings reflected Canada’s “grave concern” over the British initiative. The Canadian press responded coolly, in its turn, to Canada’s obstructiveness.8

Following the Sandys mission, Macmillan told Diefenbaker in late July that his cabinet had decided to enter negotiations with the European Economic Community. He recognized that there were substantial Commonwealth trade interests at risk, but he reiterated that only negotiations could reveal what special arrangements could be secured. On the political side, he asserted Britain’s belief that it could maintain its Commonwealth role more effectively from inside the community than from outside. He spoke of “consultation” and “close contact” with Commonwealth countries throughout the negotiations.9 On August 3 the British parliament gave its support to a British application for entry.

Canada then took its campaign to the meeting of Commonwealth ministers of finance and trade in Accra, Ghana, in mid-September, where Duncan Sandys faced twelve countries opposing British entry to the community. The debate, occupying an entire day, was framed by an opening speech from George Hees and a closing speech by Donald Fleming. Hees argued that Britain would lose, not gain, economic benefits in Europe; that Canadian trade would face “an entirely new and seriously disturbing situation … extensive damage – and in some cases, irreparable damage”; and that Commonwealth ties of “tradition, trust and trade” would suffer. He urged Britain to maintain its Commonwealth trading arrangements unchanged. Fleming made “a pleading speech” dedicated, in his own words, to “the Commonwealth and its glorious contribution to freedom, peace, human government and the progress of mankind.”10 The conference communiqué expressed “grave apprehension” over the British initiative and doubted whether the interests of Commonwealth countries could be protected. The UK delegation, in response, promised “close consultation with all Commonwealth Governments at all stages in the negotiations.”11

Christopher Young reported accurately in the Ottawa Citizen that Canada had led other nations in “ganging up” on Britain at Accra, and that they had offered Britain a choice between the European Economic Community and the Commonwealth. Having done that, Diefenbaker could not admit it. He told the House of Commons that Hees and Fleming had been misreported. A week later the Financial Times of London commented: “The extreme weakness of the New Zealand position is its strength, and the restraint with which its problems are put is far more likely to meet with a sympathetic response and understanding in London, and in the six, than the violence with which the Canadians plead their intrinsically far weaker case.”12

That kind of comment was not helpful. Diefenbaker complained to Macmillan about unfair treatment from the British press, and henceforth, in his public comments, he was careful to emphasize Britain’s right to choose and its promise of continuous consultation. “We are trying to strengthen Britain’s bargaining position in order to assist the Commonwealth,” Diefenbaker noted defensively.13 But the peevish and resentful tone never disappeared.

Britain made its formal application for entry to the community in October 1961, but did not make the text of its presentation available to other Commonwealth governments. When the chief British negotiator, Edward Heath, made arrangements to brief Commonwealth diplomats in London in early November, Drew chose not to attend, in what seemed to be a show of Canadian displeasure. That was reported in the Daily Express as a “snub”; the Observer spoke of “an openly obstructive” Canadian attitude; and the Guardian reported that the Canadians were “simmering with indignation.” The Sunday Times judged that Britain had little remaining patience with what it called “the Diefenbaker-Fleming administration.” Canadian newspapers repeated the refrain.14 All that flack prompted Diefenbaker to cable and telephone Drew instructing him to issue a statement at once “making it clear that no snub was intended”; and Drew immediately did so, declaring that the story was “absolutely false.” Basil Robinson noted that “the incident was minor but, like the Accra affair, it illustrated the difficulty Diefenbaker had in coordinating the public statements of his senior colleagues on matters where his own feelings were mixed and his signal therefore muffled.”15

As the United Kingdom pursued its negotiations over the next fifteen months, Diefenbaker kept a jaundiced eye on events, complaining frequently about the lack of consultation and taking pleasure in every sign of French intransigence. His cabinet reported increasing public distaste for Diefenbaker’s running fight with the United Kingdom.16 By the time that Macmillan agreed to a Commonwealth prime ministers’ conference on the issue for September 1962, the British hoped for a quick and successful resolution; but Diefenbaker thought that unlikely. When Charles de Gaulle finally vetoed the British application in January 1963, Diefenbaker gloated. That was a mean ending to an episode that brought him political credit neither at home nor abroad. Macmillan, who saw “all our policies … in ruins” after the French veto, must have indulged himself in a bit of black humour when he asked Diefenbaker, on the same day, whether Canada would accept free trade with the United Kingdom.17

WHILE HE WAS PREMIER OF ONTARIO, LESLIE FROST PLAYED A DUAL ROLE IN HIS relations with John Diefenbaker, as a government leader in the industrial heartland and as a friendly mentor in matters financial and political. As premier he was not always successful, especially in his attempts to alter the fiscal balance between Ottawa and the provinces. As mentor he was a patient source of counsel, whatever his disappointments may have been in his role as premier. When Diefenbaker stumbled into his conflict with James Coyne in the summer of 1961, Frost was glad to see an old difficulty faced, but appalled by the mishandling of Coyne’s departure. He offered Diefenbaker his advice on a successor; and once Coyne had gone, he moved quickly to repair the prime minister’s frayed relations with Oakley Dalgleish of the Globe and Mail This was necessary, Frost believed, as preparation for an election in 1962: “It is important from your standpoint, but also I think … from the country’s standpoint. As a matter of fact, we cannot afford to have divisions among interests whose objectives are in common.” Frost proposed that he and Diefenbaker should make a casual visit to Dalgleish at home, in order to “break the ice in a big way … His support in the business area is very important & the above ‘gesture’ would be overwhelming.”18 The meeting apparently took place, with amicable results that were evident in correspondence and Globe editorials for the next few months.

By that time Frost had decided to retire as premier. When he did so in November, he wrote to Diefenbaker to assure him that “my interest in the grand old party will remain as active as ever … To the Party I have devoted most of the active years of my life. This I propose to do in the future … I am interested in your success and the Party’s success. It will be a pleasure always to give my aid and support.”19 A month earlier, Diefenbaker had offered Frost the Canadian ambassadorship in Washington, but Frost declined because he did not wish to leave Canada – and because he felt unable to adjust to the “social rigidities” of diplomatic life in Washington. He left open the possibility of a senatorship, although he preferred to see that reward go to “others who had given long and good service.” Frost hoped instead that he could carry on with his role as facilitator and guide in relations with business and labour.20

Frost feared that Diefenbaker had lost direction and was heading for defeat in 1962. When the prime minister asked for his advice on policy in February, Frost responded at once in a series of letters suggesting an election manifesto drawing on ideas from persons inside and outside the party. In Ontario, he recalled, he “always bore in mind the fact that there are not enough Tories … to elect a Conservative government. They provide a great nucleus, but one has to go out into the highways and byways and get people, regardless of previous political affiliation and background. Many of my best supporters were people who had voted the other way a few years before.” The other parties, he knew, had impressive “brain trusts” at work. What Diefenbaker needed was “a statement of policy, a manifesto if you will, which is confident, understanding, practical and appealing … Such a thing would be morale boosting and would give our people an objective around which they can rally.” Frost appealed to the spirit of John A. Macdonald, in invocation of Diefenbaker’s great 1958 campaign.

There is a parallel today to John A’s day. In 1877 certainly the winds of change were blowing much as today. The minds of people were perplexed. John A. sensed this and had a series of great picnics and made statements of policy from which evolved the national policy, a political philosophy which pretty much dominated the scene for nearly fifty years … My suggestion is that you prepare such a statement of policy and fit into the same the multitude of worthwhile things this government has done to carry out its purpose. The government in many ways has done a very remarkable job, but I am afraid the effect of these things is going to be lost unless they are part of a composite picture of policy.21

Specifically, Frost suggested tax reductions to spur economic growth, a confident acceptance of British entry into the European community, a generous immigration policy to bring to Canada “fine people from elsewhere, with all of their skills and creative capacity,” and a general review of tax structure to reduce impediments to industry.

A week earlier, after a personal meeting with the prime minister, Oakley Dalgleish had written Diefenbaker with similar proposals to stimulate growth and to show “that your government understands the problems of business.”22 Diefenbaker told Frost that Dalgleish’s letter was “cold,” and Frost, always sensitive to the Chief’s fear of criticism, reassured him. “Please remember it was really a memorandum. In my many associations with him he has criticized me on many occasions. Very often, unfortunately, I found he was right. When the chips were down, however, with due recognition to my frailties, he helped me and he was always prepared to assist me to put my story across, provided it was right. My job was to make sure that it was such and that I could sell it.”23

This piece of counselling – both political and psychological – seemed to work. Diefenbaker met twice with Dalgleish, on one occasion for “about five hours,” to discuss both his and Frost’s proposals. He told Frost that “your ideas are excellent and the suggestions are of such a nature that I will gather together a number of the Ministers tomorrow to discuss the question at length.”24 The result was a request to both Frost and Dalgleish to give him ideas for an election manifesto. Frost responded at the end of March with a five-thousand-word paper prepared with the help of five long-time associates. “Back of this document,” Frost wrote, “I have endeavoured to weave the conception which I followed during my years in office, going back to 1943, that in this country we should create an environment in which there could be expansion and development, and in which business could grow, flourish and provide employment. In my opinion, upon that depends everything.”25 Diefenbaker promised to study the paper in detail.26

Soon afterwards Dalgleish added his own comments, emphasizing that business had to be reassured that government understood its problems and would promote growth, and that Canada’s friends abroad must be given similar reasons for confidence. There was more than implied criticism of Diefenbaker’s record in this appeal: Dalgleish noted that investors looked on Canada with “both doubt and wonderment … I acknowledge that much of this has been created and sustained by the pessimistic talk of our own politicians, and others, about unemployment, etc., over the past two years. As you know I do not believe the pessimism is justified but at the present the proof that it is not must come from us.”27

Frost’s and Dalgleish’s advice was intended to prop up a faltering regime, and above all to salvage some support for it in the business community. Parliament had reassembled in January to hear an uninspiring speech from the throne made up of odds and ends of unfulfilled election promises, plus another list of new spending promises; and the prime minister had delivered a defensive address which, in effect, accused the opposition of misgoverning the country since 1958.28 What followed was a ragged and ill-attended session, as front- and back-benchers alike took to the hustings.

Almost two years had passed since the election of a reformist Liberal government under Jean Lesage in Quebec, and by now the Quiet Revolution was transforming the province. As the pressures for fairer treatment of the country’s French-speaking minority mounted, the prime minister rejected suggestions for a royal commission on French-English relations. At the abortive cabinet meeting in Quebec City, Diefenbaker raised the subject of using French in cabinet meetings, but this was empty pretence, since Donald Fleming and Davie Fulton were probably the only two English-speaking ministers who could claim any facility in the language. At the same meeting Fleming proposed that federal government cheques should be bilingual. For six weeks the cabinet wavered inconclusively on the subject, until it agreed in February to the minister’s proposal to introduce the reform as a simple administrative change, without legislation. His announcement to the House, on February 6, 1962, was an anticlimactic response to the awakening of French-speaking Canada.29

Diefenbaker expected an election within months, but he had not decided on a date, and found it painfully difficult to do so. The Gallup Poll, which he claimed to ignore, continued to show his party running behind the Liberals. His cabinet was tired, fretful, discouraged by its public failings, anxious about its division on issues yet to be settled, disenchanted with and yet intimidated by the leader who had brought them to power five years earlier. They knew now – all of them – that he had feet of clay. What held them together was not Diefenbaker’s inspiration but the fear of defeat.

In the press gallery, an adviser told Diefenbaker in January 1962 that he faced “a dangerous degree of personal animosity among most of the members.” He attributed this not to any failings of policy, but to resentment over a loss of “the close personal relationship they had with you some years ago” and sloppy disregard for the press in ministers’ dealings with reporters before and after cabinet meetings. “The many complaints I hear,” his correspondent wrote, “seem to be highly personal, giving the impression that some who recall earlier close relationships have become progressively surprised, hurt, annoyed and finally, vindictive.” He suggested the institution of regular press conferences, which would give the prime minister a platform for his “established skill in reply and repartee” and restore a “more friendly reporting atmosphere.” “Desirable questions” could be arranged, and undesirable ones would receive considered replies that might discourage reporters from “mak[ing] up their own answers as they are doing now.”30 Diefenbaker was not, by the winter of 1962, in a mood to make the disciplined effort that this would require, and he matched the press gallery’s vindictiveness with his own.

According to Donald Fleming, the prime minister preferred to call a spring election without a budget. That would allow the cabinet to authorize patronage spending without any attempt to place it within a framework of fiscal policy – and would send the deficit skyrocketing for another year. Fleming argued with his usual passion for a budget, made his preparations, and at last got it in early April; but his appeals for spending restraint were unavailing. In late March and early April the ministry announced new federal loans for New Brunswick power projects, credits to China for additional grain purchases, new acreage payments for wheat farmers, extended freight rate reductions, more generous unemployment insurance payments, wider Maritime coal subsidies, and a frigate construction program for the Canadian navy. The throne speech had also promised increases in old age and disability pensions. The budget, on April 10, estimated a $745 million deficit despite what Fleming foresaw as a period of “rapid economic growth.” The press represented this as a modest victory for Fleming against the “big spenders.” Since the prime minister had ordered Fleming to deliver his speech in one hour, he was obliged to omit large parts of the text, to deliver the rest at breathless pace, and to ask the House for extra time. He finished at 9:50 in the evening – fifty minutes over the prime minister’s allowance – leaving Mike Pearson just ten minutes to reply. That was all he received, since the House never returned to the budget debate. One week later, after revealing the cabinet’s decision to build a causeway from the mainland to Prince Edward Island, Diefenbaker announced the dissolution of parliament for an election on June 18, 1962. The parliamentary reporter of the Montreal Star summed up the whole twenty-fourth parliament as “sometimes aimless, often ill-tempered, and always potentially explosive. Few will mourn its passing.”31

THE CONSERVATIVE PARTY, WHICH HAD FLOATED THROUGH THE MIRACLE-WORKING campaign of 1958, had lost its enchantment with the leader. On Diefenbaker’s suggestion, Allister Grosart called a meeting of key party organizers at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal in the early winter of 1962 to discuss electoral prospects. He was shocked to hear from them that, in Dalton Camp’s words, “the game was over … we’d probably lose the next election, or we’d take an awful pounding.” Diefenbaker, they said, was a liability and should be kept off television. Other ministers should be out on the road to turn the focus away from the prime minister. The dissatisfactions spilled out all day as Grosart recorded their complaints and challenged their judgments. By evening he too was a casualty: the meeting marked “the absolute end of any confidence in Allister … they didn’t believe in him and they didn’t believe he was in touch with reality and they didn’t think either that he would do anything about what they were telling him, or that he’d have any power or influence to do anything.” The day ended in a drunken banquet at which Grosart, the wine expert, tossed the first empty bottle over his shoulder to shatter on the floor behind him, as everyone sought unhappy oblivion in alcohol.32

Diefenbaker preferred not to believe the pessimistic reports. He wrote to Elmer on March 23 that polls showing Conservative support at 21 percent in the west, Liberal support at 25 percent, and 39 percent of electors undecided were wrong. “Our members in the House are very enthusiastic and are anxious for an election and certainly would not be in that state of mind if the polls mean anything. They were so far astray in 1957 and 1958, and I haven’t been advised of anything that would bear out the reports that are being given in this connection.”33 The people wanted an election, he believed. It would be “a tremendous battle,” he told another correspondent, not because his government deserved criticism, but because the air was full of Liberal propaganda. “There will be no limit to opposition attacks, however unfair … it has become regular procedure.”34

In response, Diefenbaker, on the encouragement of several supporters, was developing a campaign of attack that would cover both the Liberal Party and the New Democratic Party. The election, he said, would be a battle between free enterprise and socialism. Diefenbaker had tried out the theme in a March 1961 speech that prompted an angry response from his friendly nemesis Eugene Forsey of the Canadian Labour Congress. “Frankly,” Forsey wrote, “that speech dismayed me … I don’t think you are doing yourself or your government justice. You are making it appear that your main concern is a doctrinaire devotion to an abstract theory called ‘free enterprise,’ to which you are prepared to sacrifice almost anything; whereas it seems to me that, on the contrary, you have tackled unemployment and other problems without any such doctrinaire preconceptions, but in the traditional Conservative spirit: pragmatic, empirical, common sense, down to earth, looking for the best practical solution, whether it involves more government interference or less, more public enterprise or less.”35 Diefenbaker drafted a reply suggesting that Forsey must have momentarily lost his calm detachment out of commitment to “the socialist party.” But he thought better and did not send it.

Nevertheless the theme still appealed to him. It would allow Diefenbaker to remind voters of his 1960 United Nations speech attacking Soviet communism and imperialism; it would identify the NDP as the party of regimentation; and by free association it would link a group of prominent new Liberal candidates and advisers with the wartime Liberal regime that had “paralysed Parliament and interfered with the rights of the provinces.” It would even, at its nastiest, allow the prime minister to suggest cryptically that “softness on communism” was not something that Pearson should risk discussing. Diefenbaker tried out the broadened theme during the throne speech debate of January 1962, and he used it intermittently during the election campaign, when it ran as a discordant background melody.36

The officially advertised party program was more constructive. It was partly the product of Leslie Frost and Oakley Dalgleish’s outline of incentives to business, and partly of a draft prepared in 1961 by an informal committee under Alvin Hamilton’s direction. “To be believable,” Hamilton told Diefenbaker, “it mentions what has been done on the first stage of the national development program. To appeal to the emotions, it speaks of the principles which guide the government. To build enthusiasm for the future, it outlines the eleven point program.” The program promised a range of incentives and benefits, most of them previously announced, that marked a new scale of bidding for the popular vote out of public funds. It was matched by an equally bountiful Liberal platform. The bidding war would continue for the next twenty years.37

The prime minister’s campaign, like his previous ones, saw him crisscross the country by plane, train, and car, touching Newfoundland and British Columbia once, the Maritime provinces twice, the prairies three times, Quebec four times, and Ontario five times, usually arriving back in Ottawa overnight on Saturdays for a single day at home between weekly journeys. There were major rallies in London, Edmonton, Victoria, Vancouver, Quebec City, Montreal, Toronto, and Hamilton, and many visits to small town and rural constituencies where the party counted on fervent loyalty to the Chief.38

With none of Diefenbaker’s magnetism on the platform, Pearson took the advice of his American pollster, Lou Harris, to emphasize the Liberal team. Still, the iron law of parliamentary campaigns thrust him willy-nilly into personal battle with the prime minister. Pearson opened his campaign in Charlottetown at the end of April by challenging Diefenbaker to a television debate on the Kennedy-Nixon model. Diefenbaker scoffed and turned him down. As he had told Eisenhower in September 1960, “Why advertise your political opposition?”

Diefenbaker was incensed that someone else was doing that. Early in May, President Kennedy hosted a White House dinner for Nobel Prize winners from the Western hemisphere, at which Pearson was one of the honoured guests. In Diefenbaker’s eyes that was bad enough, but Kennedy compounded the crime in what was reported as a forty-minute private conversation with the Canadian opposition leader before the reception. Pearson told the press that they had discussed many subjects, including disarmament, NATO, and Britain’s application to the Common Market. When the departing American ambassador to Canada, Livingston Merchant, arranged what he thought would be a fifteen-minute appointment with Diefenbaker at his Sussex Drive residence to offer his farewell on May 4, he walked unwittingly into a hurricane. The meeting resulted in a flurry of tough talk in Washington and the threat of a major diplomatic incident.39

Robinson warned Merchant before the interview that Diefenbaker “was in an extremely agitated frame of mind” over the political use Pearson had made of his meeting with Kennedy. Despite the warning, Merchant was unprepared for Diefenbaker’s “disturbed and disturbing attitude.” What he heard was a two-hour “tirade” in which “the exchanges, while personally friendly, became heated.” Kennedy’s personal meeting with Pearson, the prime minister said, was “an intervention by the President in the Canadian election.” Pearson’s associates would be bound to use the meeting as evidence of Kennedy’s trust in Pearson: Walter Gordon had already done so the previous evening.

Diefenbaker added that he was “shocked” that Kennedy wished to get rid of Commonwealth preferences, and accused the Americans of thinking they “could achieve this by supporting Pearson who was prepared to accept without argument Britain’s unconditional entrance into the European Common Market.”

The Prime Minister then went on to say that Canada-United States relations would now be the dominant issue in the campaign. He said the campaigning would be more bitter than it was in 1911 and he referred to Champ Clark’s statement during the course of that campaign which it took the Canadians until 1917 to recover from. (According to my recollection, Champ Clark who was the Speaker of the House of Representatives, said publicly something along the line that it was inevitable that the United States should annex Canada. The basic issue of that campaign was the question of a reciprocal trade agreement with the United States and the outcome of the campaign was won and lost on the slogan of the Conservatives, “No truck or trade with the Yankees.”)

In his fury, Diefenbaker said he would have to confront the Liberal line head on – the claim that Pearson could better handle relations with Washington. “He thought he would probably be forced into this by the middle of or end of next week.”

In countering the Liberal line, he said he would publicly produce a document which he has had locked up in his private safe since a few days after the President’s visit to Ottawa last May. This document he says is the original of a memorandum on White House stationery, addressed to the President from Walt Rostow and initialled by the latter, which is headed “Objectives of the President’s Visit to Ottawa.” The Prime Minister says that the memorandum starts:

“1. The Canadians must be pushed into joining the OAS.

“2. The Canadians must be pushed into something else…

“3. The Canadians must be pushed in another direction …”

Diefenbaker told him, falsely, “that this document came into his possession a few days after the president left, through External Affairs, under circumstances with which he was not familiar, but his understanding was that it had been given by someone to External Affairs.” This authoritative evidence of the American intention to push Canada, Diefenbaker told Merchant, “would be used by him to demonstrate that he, himself, was the only leader capable of preventing United States domination of Canada.” The prime minister added that an investigation was under way to determine whether “some Liberal supporter of Pearson” in the Canadian Embassy in Washington had set up the interview with Kennedy. The incident, Diefenbaker said, would “blow our relations sky high.”

Merchant reported that Diefenbaker was tired by an overnight flight from Newfoundland, where he had experienced “an exhausting and frustrating whistle-stop campaign,” and that he was uneasy about his keynote address planned for that evening in London, Ontario. “He was excited to a degree disturbing in a leader of an important country, and closer to hysteria than I have seen him, except on one other possible occasion.” Merchant felt that Olive was concerned about his state: She was “hovering over him when I arrived and obviously doing the same when I chatted with the two of them for about ten minutes before departure.”

Merchant attempted a response, and reported that Diefenbaker was “willing to hear me out.” He told the prime minister there was no reason to criticize Kennedy for taking the occasion to discuss international affairs with a prominent Canadian visitor. “It was childish to assume that this constituted any effort or intent to intervene in Canadian domestic politics.” He offered his word that the US administration had no favourite party in Canada, and assured him of the president’s great personal respect. But he implied that Diefenbaker was lying about how he had obtained the document, and delivered a stern diplomatic warning. “I urged him in strongest terms to discard any thought of revealing publicly the document which he said he had in his possession. I said that I had never seen or heard of it and that it was not conceivable to me that if such a memorandum were genuine, it could have been transmitted officially or unofficially to anyone in the Canadian Government.” If the document was genuine, it was confidential advice to the president which “had no official status and was not intended for Canadian eyes. Moreover, I said that were he to reveal it publicly, there would be a serious backlash, if not in Canada, then certainly in the United States. People would ask how the Prime Minister had come into possession of such a privileged internal document addressed to the President of the United States, and why it had not been immediately returned, without comment or publicity.”

Merchant felt he had made an impression on Diefenbaker, but could not be sure whether the prime minister would refrain from using the Rostow memorandum in the campaign. He had known Diefenbaker, at other times, to be agitated “only to find that two or three days later the storm had passed. On this occasion, however, his only assurance as I left, was that he would not raise this issue tonight, and in fact, he said half jokingly… that he would not bring it up until I had left Canada, since, as he said, it would be up to another American Ambassador to pick up the pieces and he didn’t want to spoil my last few days in Ottawa.”

The ambassador concluded: “We have a problem.” At best, having blown his top, Diefenbaker would think again and act responsibly. “It is necessary, however,” he advised, “that we take out any available insurance against the worst.”

Merchant told George Ball that there was nothing to gain by interference in Canadian elections, or in the appearance of doing so. A successful intervention would label the winner as “a running dog of the United States” who would be “inhibited from acting along lines agreeable to us.” After an unsuccessful intervention, “the winner would hate us.” Since appearances had now given Pearson an advantage, he suggested some balancing gesture in Diefenbaker’s favour, such as a quickly staged and informal meeting between Kennedy and Diefenbaker, arranged at the president’s initiative.

As Merchant intended, this message was conveyed at once to the president. Kennedy’s national security adviser, McGeorge Bundy, gave detailed instructions to Ball on a response, and Ball passed these on to Merchant on May 8, along with a copy of the original Rostow memorandum.40 In a footnote for Merchant’s information only, Ball said tartly that Kennedy had “no intention or desire” for an early meeting with Diefenbaker. The prime minister was on the campaign trail in Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, and Alberta during the week, so Merchant asked to see him as soon as he returned to Ottawa on Saturday, May 12. Merchant hoped that “the cryptic nature of my message will exert restraint on him,” although Diefenbaker had threatened “at some Quebec whistle-stop last night” to discuss the subject of a Canadian-made foreign policy later in the campaign.41 While awaiting Diefenbaker’s return, Merchant met with Robinson and conveyed Washington’s concern about the general course of Canadian policy and the prime minister’s “tirade.” He told Robinson he had a message from Kennedy which, he hoped, “would have a restraining effect.” Robinson, who was now due to be posted to the Canadian Embassy in Washington, left the meeting “overwhelmed by the size of the problem of explaining Canadian policy in Washington, especially on defence.”42

Diefenbaker received Merchant at home on Saturday evening. The ambassador’s instructions called for a coy diplomatic dance, which he performed. Afterwards, he reported the interview by telegram to Washington.

I opened by saying I had delayed my departure by reason my grave and growing concern over our talk on May 4. I said I had not reported to the President his stated intent to reveal in present campaign his possession of confidential document of the President presenting advice of member his personal staff. I said I had only reported to the Department his belief Pearson intended capitalize in campaign on private conversation with the President on Nobel Prize occasion which I said had been informal twenty-minute chat in advance of formal dinner. Then I said I had independently obtained copy Walt Rostow’s memo which I found unexceptionable and concerning four subjects which had been frequently discussed and regarding which I had thought PM’s personal attitude favorable. Verb “push” I said corresponded to British “press” or Canadian phrase “seek to persuade.”

PM did not interrupt as I went on to say that I had not reported his threat to use existence or contents memo because consequences of his doing so would be catastrophic. PM interjected “they would be so in Canada.” I said I was not talking of Canada but of reaction in the US. I said if he did this the result in the US would be of incalculable harm with public opinion, in the government and in his personal relations and that consequently I had delayed my departure to urge once more that he abandon any such thought.43

Diefenbaker backed down. He told Merchant that “he had given [the] matter further consideration and in light of what I had said to him on May 4 he had no present intention of using or in any way referring to [the] memo in question. He said if he changed his mind he would personally telephone me in Washington before doing so but he was now decided to discard any such thought.” According to Diefenbaker, only three other persons knew of the memo – Green, Fleming, and Churchill, whom Merchant described to Ball as “all … cool steady men.”44

Merchant noted that Diefenbaker then set off on an “emotional sidetrack” by insisting that the United States was “trying to push” Canada around, but calmed down when the ambassador asked what evidence he could show for such suspicions. He turned instead (“with Gusto”) to the subject of his prairie campaign tour, though bemoaning the time and travels still ahead. The ambassador concluded his report optimistically. “Notwithstanding fact PM nervous and in my judgment on verge of exhaustion, I believe storm has passed and that chances are now minimal that he will embark on all-out anti-American line … At end conversation we both lowered our voices and with complimentary close he bade me warm good night.”

For the time being an understanding had been achieved, but the incident remains puzzling. If Diefenbaker, in a fit of anger and desperation, intended to use the Rostow memorandum, why did he warn Merchant beforehand? Was he hoping to be dissuaded from what would have been a dishonourable and self-destructive act? Did he expect that his threat would lead Kennedy to refrain from any further “intervention”? Why did he lie about the origin of the memorandum, in a way that could only be obvious to Livingston Merchant? Merchant later said that Kennedy had been “astounded and indignant” at this “species of blackmail,” and that he was himself “baffled and finally appalled by Diefenbaker.”45

Merchant’s and Robinson’s observations – that Diefenbaker was “disturbed,” “overwrought,” “extremely agitated,” “excited to a disturbing degree,” “closer to hysteria than I have seen him,” “on the verge of exhaustion” – suggest a man on the edge. Perhaps his threat was not the act of a carefully calculating politician, but of an unsettled – and very fragile – spirit.

Despite his expressions of confidence, Diefenbaker was aware that his government and party were in trouble. The political atmosphere had changed since 1958, and the high expectations of that winter campaign could not be revived. Yet his own confidence and sense of stability rested on continuing signs of public support. The government had borne one critical blow after another since the cancellation of the Arrow in 1959. The prime minister’s moodiness, disorganization, and indecisiveness had undermined the confidence of his own cabinet. Diefenbaker was also bewildered by the complex technical questions of economic, financial, and defence policy that now overwhelmed his ministry. He had managed – temporarily – to contain the nuclear weapons issue, but the others were more immediate.

In the days before his first interview with Merchant, the prime minister faced a perplexing monetary crisis, and on May 3 it became public. The Canadian dollar – alone among the major currencies and in defiance of the fixed exchange rate policy of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – floated in value on the international markets. From a position in the late 1950s when it stood at a premium against the American dollar, it drifted gradually downwards to a rate of about 95 cents US by the winter of 1961-62. The persisting Canadian recession, five consecutive budget deficits, an increasing deficit on the current trade account, and, it seemed, general uncertainty about the policies of the Diefenbaker government had unsettled the exchange markets. Once the election was called on April 18, an unanticipated stampede in the sale of Canadian dollars began. In the month of April alone, the Bank of Canada’s exchange fund sold $125 million of its foreign reserves to maintain the value of the Canadian dollar. That brought the decline in the exchange fund over seven months to about half a billion dollars, or one-quarter of Canada’s total exchange reserves.

The government’s chief financial advisers believed that Canada faced a continuing speculative run on the dollar and a potentially disastrous decline in its value. Diefenbaker was informed by Robert Bryce on April 29 that there was an exchange crisis, and senior officials met with Donald Fleming to discuss alternative responses. When they could not agree, Fleming recommended that the Canadian dollar should be pegged at 92.5 cents US. He gained Diefenbaker’s reluctant support for an approach to the IMF to approve the decision, and subsequently arranged for a special meeting of the IMF board for the evening of May 2 in Washington. Early that morning Diefenbaker telephoned Fleming to say he had changed his mind, but Fleming and his officials insisted that the process was under way and could not be reversed. Diefenbaker told him: “It will cost us the election,” and gave way. Cabinet, in the presence of eight ministers under Fleming’s chairmanship, ratified the recommendation, and officials set off for Washington to present the proposal to the IMF board. Meanwhile, Fleming flew back to Toronto for his nomination meeting, where he made no mention of the devaluation. The decision was announced to the press at 11:15 that night.46

Diefenbaker suggested in his memoirs that the policy was mistaken; that Canada should have supported the floating value of the dollar through the election by selling reserves; and that it should have moved to a fixed exchange rate in an orderly way in the next budget. Instead, he claimed, it was forced to an emergency devaluation because the Kennedy administration “spooked” the New York money market “to get rid of my government.” In this American conspiracy Diefenbaker saw the complicity of officials from the Department of Finance, “powerful interests” on Bay Street, the CBC, and the Liberal Party. The Liberals did, indeed, take advantage of the crisis – once devaluation had occurred – to ridicule the competence of the Diefenbaker government.47 But there is no need for so elaborate an explanation of the affair. Diefenbaker admitted he had “no direct proof for his claim, and there were enough objective reasons to explain the run. Once it had begun, pegging at a lower level, with IMF support, offered a reasonable means of stemming the tide.

Diefenbaker’s conspiracy theory had apparently not taken form at the time of devaluation. If it had, he would certainly have added it to his catalogue of Kennedy’s offences when he met Merchant on May 5. But the disturbing evidence of a government that had lost control – something that was bound to feature in the rest of the campaign – preoccupied and unsettled him, and he went into the meeting with Merchant carrying that burden of anxiety. Harold Macmillan had also spent a day in Ottawa after his latest visit to Washington, asserting his commitment to the Common Market negotiations and emphasizing the president’s eagerness to support those efforts.48 If there were no great conspiracies confronting the prime minister, fortune, at least, was not working in his favour as it once had done.

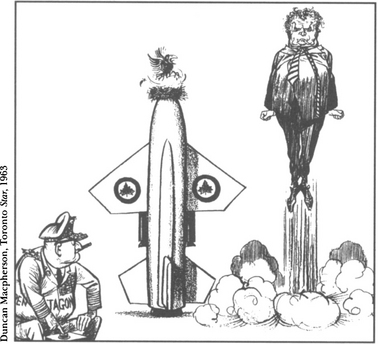

The devaluation, which offered trade benefits for Canada, occurred in the worst possible political circumstances. A Winnipeg Free Press cartoonist lampooned Donald Fleming hoisting the remnants of a dollar to the mast. Jokes about the “Diefendollar” or “Diefenbuck” swept the country, and phony green bills with mutilated ends were soon circulating from St John’s to Whitehorse. The easily caricatured administration seemed to have become its own caricature.

Diefenbaker was convinced that few of his ministers were pulling their weight in the campaign. Alvin Hamilton made an imprudent remark about a cabinet compromise on the dollar’s value and suggested that he preferred a value of 90 cents US. Donald Fleming tried to explain the exchange crisis, but was too abstract. Ellen Fairclough had mysteriously avoided the press in a campaign visit to Vancouver, and in mid-campaign the prime minister complained that “19 Ministers have cancelled out the meetings arranged for them. I want the daily record of any Minister who did that.”49 In Quebec, a report to Diefenbaker early in the campaign suggested that the organization was “completely ineffectual” and doing nothing.50 Apparently the leader would have to count on nothing more than his old magic on the platform.

In London, Ontario, the prime minister was joined on stage by Leslie Frost, his successor John Robarts, and most of the federal cabinet. Diefenbaker opened the campaign by defending the government’s record and laying out a tedious “prosperity blueprint” – the Hamilton-Frost mélange of spending promises and business incentives, which did not add up to a coherent or inspiring program. The audience stewed in 90-degree heat and was not roused.51 By mid-May Diefenbaker was complaining publicly about complacency among Conservative supporters. Later in the campaign, when he went on the attack, he could still bring his audiences alive with his furrowed brows, jokes, insinuations, and one-liners. Pearson’s brains trust, he said, was “a cacophony of paragons, pseudo-economists, economic centralizers, and former bureaucrats.” In the west he offered more promises of aid, and met his hecklers wittily – including a gaggle of Doukhobor women in Trail, British Columbia, who stripped naked before him – until the mass meeting in Vancouver on May 30.52 That night he faced an arena audience of 7000 that was well sprinkled with protesters. Diefenbaker kept his temper in the face of constant interruptions, but could not silence them. Charles Lynch described the scene: “With the concessionaires taking a hands-off attitude, the prime minister was left to cope with the situation himself. Perspiring, running his hands through his flying hair, his eyes flashing, he talked of organized anarchy. He said he liked good fun too. He spoke of an Elizabethan sense of a grand design for Canada. He hammered on unity. All this was to no avail … John Fisher, bathed in perspiration, kept scribbling notes and passing them up to his chief … nothing seemed to work.”53

Two days later, in Chelmsford, Ontario, the Diefenbakers faced “the ugliness and invective of a hysterical mob” as they made their way to their car with the local Conservative candidate. Diefenbaker used the demonstrations to suggest planned obstruction by the Liberals and the NDP: “They thought they silenced that speech, but they did far more for the Conservative party than all the speeches of the campaign.” On June 7 Joey Smallwood handed Diefenbaker the evidence of collusion by forcing the St John’s Rotary Club to cancel its invitation to Donald Fleming to address them on devaluation. An exhausted Diefenbaker found himself refreshed and aroused when cast in the martyr’s role.54

When the Liberal Party advertised its claim that devaluation would bring higher prices for consumers, Diefenbaker issued a stern warning to the big companies: “I don’t want any group or corporation in this country no matter how successful they may be, to take advantage of this situation. I serve notice here and now that if, in the next few days, this kind of thing is going on there will be action as effective as it is drastic.” That left producers and retailers puzzled and fearful. Alvin Hamilton added his own threat that the government might undercut oil prices by building a national oil pipeline to Montreal.55

Despite outbursts of the old fire, Diefenbaker rarely created the excitement of 1958. But his challenger Mike Pearson aroused even less enthusiasm on the platform. By early June reporters were widely expecting a minority parliament. They watched rural Quebec with special fascination as the colourful leader of the Quebec Social Credit Party, Real Caouette, brought out the crowds in the Quebec City, Saguenay, and Beauce regions with his rough-hewn words and promises of bliss. As the campaign ended, the prime minister appealed more and more to ethnic and anti-American sentiments. At the Ukrainian Hall in Montreal on June 11, he joked bitterly about the abuse of his name: Diefenbucks, Diefenbliss, Diefenbunkum; double, double, Diefentrouble/Diefenboil and Diefenbubble. “If I didn’t have the name I have I don’t know what the Liberal party would do … The playing with my name indicates what they think of those of non-French and non-English origin.” He reminded his audiences that he was the leader who had dared to confront Khrushchev at the United Nations, while Pearson was curiously soft on communism. In the prime minister’s leaping rhetoric, Pearson had become simultaneously the candidate of big business, John Kennedy, and Nikita Khrushchev. Diefenbaker was the candidate of the people – except, it appeared, in rural Quebec, where Caouette matched his populism.56

In the last three weeks of the campaign, the Liberal lead in the Gallup Poll narrowed from 44-36 percent to 38-36 percent as voters drained away to the NDP and Social Credit. Diefenbaker and the Conservatives held their own. The Globe reported that “there is a vague, difficult to measure lack of confidence in Canada’s political leadership of any stripe … The Conservative campaign has been essentially a one-man show with Mr. Diefenbaker the man. If they fail to win, he must take the blame; if they do win he can claim the victory, no matter how many seats they lose, for his own.”57

Oakley Dalgleish offered the Globe and Mail’s measured support for the Diefenbaker government in a front-page editorial on June 5. The Liberals had offered “negative and destructive criticism,” and had spent their time in opposition “fashioning new planks to fasten on the shaky structure of the Liberal Welfare State. Liberal irresponsibillity has been amply demonstrated in this campaign. While the party spokesmen have gone about the country heaping criticism on the Government’s budget deficits, alleging financial mismanagement, they have simultaneously promised, if returned to power, to launch vastly expensive new schemes for health and welfare and capital programs. The Liberals, in fact, have been consistent only in their inconsistency.” “Our readers,” the editorial continued, “will not need to be reminded of the occasions – far too numerous for our liking – when we have felt it necessary to criticize the Conservative Government in sharp terms.” But those criticisms were usually directed not at its decisions, but at “its methods of implementing them.” Sometimes the government had gone “too far, too fast,” in redeeming its promises, but it had met those promises “more faithfully than any government since the turn of the century.” Now Diefenbaker promised that the task of his government would be to create the business climate “to pay the bills and meet the challenge ahead,” and he was bound to make “a sincere effort to translate these words into national policy.” The editorial concluded: “On the record of the parties, without minimizing the mistakes of the past Conservative Administration, the Government, in our opinion, should be given a vote of confidence by the people of Canada.”58 That was no ringing endorsement, but it matched the sceptical mood of the country in the summer of 1962. The Montreal Gazette commented that the prime minister had “failed to make an effective appeal to Quebec, despite the fact that he has enlarged the flow of money to this province to a remarkable extent.” In general, he had “left the impression of blurred aim and clumsy method.”59 The Edmonton Journal, which had supported Diefenbaker in 1958, switched its allegiance to the Liberals.

John and Olive were on their railway car in Prince Albert for election day on June 18 after a final rally in Hamilton and a weary appearance on national television over the weekend. The first news from the Atlantic provinces showed the Tories losing about a quarter of their seats to the Liberals; but as the polls closed and the count moved to Quebec and Ontario, the outlook darkened. In Quebec the Créditistes decimated the Conservatives in the countryside, taking twenty-six seats, to thirty-five for the Liberals (a gain of ten) and only fourteen for the Tories (a loss of thirty-six). In Ontario the Conservatives held their edge outside the cities, while the Liberals and the NDP made huge urban gains. The Conservatives were down to thirty-five, a loss of thirty-two seats. The government would be saved or overthrown in the west. Across the prairies, Diefenbaker’s followers kept the faith: The Chief held forty-two of forty-eight ridings. In Saskatchewan the Conservatives actually increased their popular vote over 1958. Finally, maverick British Columbia split four ways to steal the majority away. Next morning Diefenbaker surveyed the wreckage: He held 116 seats to the Liberals’ 100, Social Credit’s thirty, and the NDP’s nineteen. Five ministers – David Walker, William Hamilton, Noël Dorion, Jacques Flynn, and Bill Browne – had been defeated. The loss of ninety-two seats was devastating and incomprehensible. But the minority victory kept Diefenbaker clinging to power against an opposition whose unity was uncertain. Groping for words to a reporter, the prime minister took refuge in some typical advice of Sir John A. not to do anything quickly: “Precipitous action did not always result in wise decisions.”60

Overnight, the Conservative Party had been transformed, in parliament, into a rural, English-speaking minority party. The Liberals and the NDP swept the cities, where they took over half the popular vote to the Tories’ one-third. Even the ethnic vote was lost to the Liberals and the NDP; and young voters, similarly, turned away from the Conservatives. John Diefenbaker kept his strength among western farmers and the beneficiaries of his party’s regional development grants. Those were narrow constituencies. The Liberals were disappointed that they had failed to overcome the government at a single blow, but the initiative had passed to them.

While Diefenbaker absorbed the electoral setback, he was faced with a second and more serious exchange crisis as he flew back to Ottawa. From the end of May the Bank of Canada’s exchange fund had been forced to renew its massive selling of US dollars after a three-week respite. On election day alone, $41 million was sold into the exchange market, and in the next two days the bank’s reserves fell by a further $110 million in the effort to maintain a 92.5 cent Canadian dollar. The speculators had descended in a horde, expecting a further devaluation as Canada exhausted its reserves. Fleming, with Diefenbaker’s approval, was determined to maintain the dollar at its pegged rate, which required quick and massive support for the exchange fund from abroad. Louis Rasminsky and the senior officials of the Department of Finance rushed to design a program of borrowing and economic restraint that would meet the conditions of the International Monetary Fund and the foreign banks, and on June 20 the cabinet went into five days of continuous session to argue over its acceptance. Every hour was crucial, as reserves continued to decline by more than $40 million each day.61

Predictably, Diefenbaker appointed a committee of cabinet to meet with Bank of Canada and departmental officials, and wrangling continued into the evenings. The immediate need was to convince international lenders that the budget deficit would be reduced and the adverse trade balance improved. The prime minister judged such action to mean that “those in the bureaucratic and financial communities” had seized the opportunity of the crisis “to bring about a reversal of the declared fiscal policy of my government.”62 In the sense that “the declared fiscal policy of my government” was an unending series of budget deficits accumulated on political grounds, that was correct. As the reserves declined, the government had no reasonable options. Diefenbaker explained the reversal in his memoirs:

Having failed to win a majority, we had now to stop the run on the dollar by other means. We were a minority government with a crisis on our hands. I had little choice but to accept the advice of the senior officials as to a program of emergency measures. Our exchange reserves had now fallen below the $1,000 million level, which these officials contended was the minimum we could safely hold. There was a danger that they could vanish entirely within a month or two, leaving us at the mercy of the market from day to day. The essence of the problem was to regain the confidence of foreign and Canadian investors in the Canadian dollar. The fact that they were wrong in feeling that we were not paying enough attention to “sound” financial policies was no longer the point. They were the ones whose opinion was important now.63

On Sunday morning, June 24, cabinet agreed to a package of emergency measures: temporary tariff surcharges ranging from 5 to 15 percent on about half of the country’s imports; reduced exemptions from customs duties for Canadian tourists returning from the United States; a reduction of government spending amounting to $250 million annually; and Canadian borrowing of over a billion dollars (US) from the IMF, the American Export-Import Bank, the US Federal Reserve, and the Bank of England. That evening Diefenbaker issued a press statement announcing the austerity program before the opening of Monday’s markets; and the next evening he made a national radio and television broadcast to explain his government’s measures. Simultaneously the Bank of Canada set its rediscount rate at a record high of 6 percent. Diefenbaker insisted that the action was temporary, intended to “relieve the pressure on the Canadian dollar in the exchange field, to bring about greater stability in our international transactions and to strengthen our exchange reserves.” He said that further, long-term measures would be introduced to improve the country’s current accounts, and he called on Canadians to unite in common purpose to support his actions. Surprisingly, he did not recall parliament to discuss the crisis. “I think it well,” he commented, “that Parliament should not meet until after a cooling-off period so that time will be given for political passions to subside and be followed by calm reason which, I have always found, is the basis of effective discussion and consideration.”64 The government, battered and bruised by election losses and the exchange crisis, needed time to regroup.

While the prime minister struggled in cabinet over the austerity program, Leslie Frost wrote to Diefenbaker to reassure him that “you are the only Conservative leader since John A.’s passing in 1891 who has managed to keep on top of the heap through three successive elections. I think this … adds to the measure of people’s appraisal of your personality and ability to meet the challenge of these days and following.” He added that the troubled financial and political situation was a “ready made situation for a leader who will grasp the nettle with both hands.” That meant moving Donald Fleming out of the Department of Finance.

Much as I like Donald, I do not think he can give the confident direction that is required. I think this job is for yourself … By actively assuming the leadership of the tops in industry, business and finance you can be unassailable and none of the competing parties could challenge you. If they do you would have built up a body of opinion which was lacking in this last election which would be enough to turn the scales. I am quite satisfied that our people are prepared to be told what they have to do. We have to work hard, tighten our belts and devote everything to development and expansion.65

This was encouragement to make the economic changes then being forced on cabinet, and to seek renewed alliance with the alienated business and financial communities. When Diefenbaker announced the government’s emergency program, Frost wired two messages of congratulation. The second was a concise sermon: “Remember the positive side more exports hard work lower costs employment. Business incentives in other words an aggressive determined people aiming at a greater more prosperous country.”66

Harold Macmillan also had words of comfort. On June 22 he wrote to say that he was working with the Bank of England to provide assistance in the emergency, and he added some armchair philosophy which pointed more to his own political difficulties than to Diefenbaker’s. “You and I, who have been through the ups and downs of politics, know what a rough life it is. We here are having, as you have had, a strange movement away from the older Parties, which is perhaps a sign of the spiritual pressure upon young people today and the long drawn out contest between East and West. We older people know that it will last our life-time but the younger ones hope to see some sign of dawn. However, whatever the reason, it is rough going.”67

A few days later Davie Fulton offered his advice from the inside. He thought the government’s problem was one of both image and substance – and elaborated on the theme over seven pages. The government’s image “generally was bad”; it was insufficient explanation to say, as Diefenbaker had complained during the campaign, “that Ministers did not get around the country enough or failed to make enough of the right kind of speeches. The trouble was that no coordinated presentation of the work of the Government as a whole was ever developed – or at any rate it was certainly not sufficiently developed, or developed in time.” Before the next election, which he expected soon, Fulton insisted that “a strong picture should emerge of a Government which, even under the present difficult circumstances, accepts responsibility to govern and grapples on a planned basis with the problems now confronting us and introduces programs to meet both the short and the long-term needs of the country.”68 This was criticism that no minister had dared to offer before June 18.

Fulton accused the prime minister of making a false claim about the exchange crisis; what was worse, the claim was not believable. “The question is being raised: How could a situation of such proportions have arisen only in a few days? This in turn leads to the suggestion that the true facts are not being told.” The government had to speak quickly and truthfully in a policy statement that would guide all ministers.

My suggestion is that the general effect of the statement would be to remove the impression that we are saying that the crisis developed only after the Election. We should, on the contrary, admit that the situation was serious prior to the Election (that is, during the campaign) and we should not minimize the fact that we took the action of pegging the dollar to meet a situation that was serious. We should not pretend otherwise. We should go on, however, to point out that the situation did not reach crisis proportions until just before actual voting day and in the four days immediately following.

…It seems to me to be … particularly essential to guard against the possibility of Ministers in their individual interpretations continuing to suggest that there was nothing to worry about until the Election was over – and then something suddenly developed. The public simply will not buy this and it would play into the hands of our opponents.

While his emphasis was on public relations, Fulton made clear that his worries related to deeper inadequacies in the government’s performance. His letter came close to a declaration of non-confidence in Diefenbaker’s leadership. Privately, Fulton had certainly lost that confidence.69 Diefenbaker was shaken by Fulton’s accusation that he had misled the public.70

The election results, the exchange crisis, severe press commentary, and Diefenbaker’s correspondence all pointed to the need to give the cabinet a new face. Diefenbaker knew it, although he could not admit that he had actually done anything to justify the public’s loss of faith. Partly, the problem was to replace five defeated ministers; partly, it was to shift the two ministers – Fulton and Fleming – who seemed to threaten his confidence most directly; partly, and most urgently, it was to recover some support in the business and financial community. The prime minister cast about desperately for advice, and in his conversations with Gordon Churchill he talked frequently of resignation.71

In that atmosphere Oakley Dalgleish offered his frank counsel, which he hoped would not seem “an impertinence.” He recalled his previous support for Diefenbaker since 1956, and especially his suggestions after the 1958 victory that Diefenbaker should create an inner cabinet of half a dozen strong ministers and an advisory group of “proven and respected business and financial men to consult on … fundamental policies … I mention these conversations now, simply because they define the steps which I now urge on you. With the right group of consultants you can overcome the obvious deficiencies in the cabinet. Moreover, I am confident by this means you can take action on several fronts (which still needs to be taken) boldly and confidently, in the knowledge that the business community will co-operate and that the Liberals will have to go with you.” Dalgleish told Diefenbaker that he wrote as a friend, not a partisan, “who shares your aspirations for this country.” He pledged his own and the Globes aid in doing “anything and everything we can in the cause.”72

The next day the prime minister’s old confidant Bill Brunt, to whom Diefenbaker had just offered the speakership of the Senate, was killed in a car crash as he drove home to Hanover, Ontario. Brunt, like David Walker, had been his loyal supporter, electoral financier, and counsellor since 1942. Now Diefenbaker had lost one in defeat and another in death within three weeks.73 The burdens grew heavier.

On July 12 the Diefenbakers attended Brunt’s funeral in Hanover, in the course of which the prime minister talked at length with Leslie Frost. In his desperation, Diefenbaker proposed that Frost should join the cabinet as minister of finance – and once more, as in the previous autumn, Frost declined. His first response was lengthy and ambiguous, reasserting the view that his best service would be as an informal link to the business community and repeating most of Dalgleish’s pro-business advice.74 Diefenbaker noted on July 16 that “I phoned Frost and said I could not make anything out of his letter and would like to know what he meant.” He meant no – but Frost suggested that Diefenbaker should let Dalgleish explain.75 Diefenbaker persisted, in several telephone conversations with Frost and Dalgleish. Failing acceptance of the Finance portfolio, the fallback was a senatorship. Frost resisted all the prime minister’s pleadings.76

Instead, he and Dalgleish proposed that Diefenbaker should invite Wallace McCutcheon of the Argus Corporation to join the cabinet. McCutcheon was unknown to Diefenbaker, and Frost recalled that the prime minister “was most diffident.” Over several weeks, with no other prospects for strengthening the cabinet from Toronto, Frost and Dalgleish wore Diefenbaker down. McCutcheon was willing. He would resign his directorships and accept appointment to the Senate as a minister without portfolio. By early August Diefenbaker was reluctantly convinced, and at the same time smugly satisfied that he had mended his bridges to Bay Street.77

Meanwhile he was juggling other possible changes in cabinet with his usual uncertainty – a state worsened by exhaustion, the gloom of defeat, and personal grief. On July 13 Diefenbaker was stunned by the news that Macmillan had brusquely dismissed one-third of his cabinet, including the chancellor of the exchequer. This was ruthlessness beyond Diefenbaker’s capacity and temperament. “I wish,” he told Elmer the next day, “that I had enough members to make possible a general reconstruction, but that is impossible.” 78

The old cabinet met weekly for routine business while Diefenbaker shuffled his lists and hesitated. On the weekends he retreated with Olive to Harrington Lake, where she urged him to get away for a longer holiday. On July 21, as he stepped off the verandah onto wet grass, Diefenbaker turned his ankle in a gopher hole and heard “a sharp snap followed by severe pain and swelling.” He had broken a bone, and was sent to bed by his doctors – who may have been prescribing for low spirits as much as for a broken ankle.79 “Their advice was medically sound,” Diefenbaker wrote in his memoirs, “but politically disastrous. An invalid’s bedroom is neither an ideal place for Cabinet meetings nor a location suited to keeping track of the political manoeuvrings about one. But flat on my back I remained.”80 His secretary, Bunny Pound, suspected that he had chosen the accident: “Dief didn’t want to go to the office … he wanted to be by himself for a while … so he fell in the gopher hole. This was sort of psychological. He didn’t want to have any of this trouble. He just wanted to sit there in his bed, and grumble and growl and think about things … I think, possibly, he realized that he had bitten off more than he could chew. He had all of these talents, all this sort of semi-genius, but he had no control over it.”81 By mid-August, however, he was reassuring his brother that “I have been around the house now for several hours during the last few days and should be out of here soon.” As he compared himself with “other members of the Cabinet whose health has been undermined by work,” he reflected gratefully that “I have been so fortunate in not having been laid up at any time since becoming leader of the Party in 1956, excepting one mishap in January 1959 and the present one. I do not recall when I have been in better health.”82

Diefenbaker had steeled himself to move Donald Fleming from Finance and Davie Fulton from Justice, and at the end of July he began meeting ministers to discuss the changes. Fleming recalled that when they met, Diefenbaker spoke with “disarming frankness … wistfully,” as “a sorely troubled, almost beaten, man.” Fleming recorded his words. “Don, you and I are in the doghouse. I think you should be relieved of the portfolio of Finance. You get the blame for everything, and it’s hurting your future chances. I think you should have a portfolio that will give you a fair opportunity. I don’t know how we will replace you in Finance. You know more about finance than anyone else in the House of Commons. In fact, you know more about finance than all the rest of the House of Commons put together.”83 The minister was struck by Diefenbaker’s “unchallengeable sincerity,” and concluded that “I must aim to be helpful, constructive and, above all, unselfish” as the prime minister struggled to keep the foundering ship afloat. He accepted Diefenbaker’s wish that he should move to Justice, providing Fulton understood that the choice was the prime minister’s.84

Negotiation with Davie Fulton was more troublesome. Diefenbaker began aggressively by claiming that “I found it difficult to speak fully with him because if the future was anything like the past it would find its way into the papers.” He cited two incidents, most recently their December 1962 conversations over the previous cabinet changes. Fulton denied that he had passed reports of their private talks to reporters for personal advantage: “Mr. Diefenbaker, that’s quite wrong, and if you persist in thinking that I am disloyal to you on a personal basis, there is only one course: you must ask for my resignation.” Diefenbaker did not want that, and told Fulton he would be moving to National Revenue. Fulton replied that he could not accept such a demotion. On August 9, the day when Diefenbaker expected to announce his new cabinet, Fulton proposed Public Works as an alternative. After consulting his ministers informally, Diefenbaker agreed. But Fulton was alienated and already thinking about a move back to British Columbia to contest the provincial party leadership in the new year.85