1963-1966

THE TELEGRAM was unrelenting. THE DAY AFTER DIEFENBAKER’S TRIUMPH in caucus, the lead editorial accused the prime minister of putting his own interest above that of the party: “John Diefenbaker yesterday decided that the sacrifice of his personal position as leader of the Progressive Conservative Party, and Prime Minister until April 8, was too great a price to pay to save his party, and perhaps his Government.”

The political magic and force of personality that had once swayed thousands was strong enough to win support for his position from his party’s caucus and his cabinet colleagues. But the Conservative Party, including many of the members who yesterday pledged their support mingling cheers with tears, will pay dearly for this decision.

The party, as a political entity, is split as never before. The members will pay their account on election day as many of them undoubtedly must realize even now. The Prime Minister will lead his party into his fourth campaign, and has the satisfaction of knowing that no cabinet colleague was strong enough to unseat him, and only one had the courage to leave him.

It is impossible to say what price will be paid for this leadership and this satisfaction of Mr. Diefenbaker, but it will be huge in terms of political currency.1

The prime minister, said the Telegram, had no reasonable policies for electors to judge: “no budget … no Government defense policy … no long range economic plans; no tax reforms; no … trade policies since Britain’s failure to enter the Common Market … no comprehensive role for Canada in world affairs.” He had just two lines of attack: “First, United States interference in Canadian political matters and, secondly, that the opposition parties obstructed the business of Parliament. The Telegram believes that Canadians will not accept either premise as a sound basis for returning the Government to office.” The Chief’s resignation would have been far better, offered now, “still in office, and thereby giving his party a fighting chance under new leadership, than later, shattered at the polls and reviled by the unforgiving and the unremembering.”

Next day the Globe and Mail took different but equally deadly aim in its lead editorial, “A Matter of Morality.” Its targets were George Nowlan, George Hees, and Wallace McCutcheon, the ministers who had come out of caucus denying any revolt in cabinet against the prime minister’s leadership. They were lying.

It is a matter of fact that some Ministers of the Crown who on Wednesday declared their allegiance to the great leader had, only two days before, their resignations ready in their pockets. It was to be the Prime Minister’s resignation or theirs.

Today the Prime Minister is still in office and the rebels, having deserted their cause, are still in the Cabinet. They have purchased their jobs, for a few weeks, doubtless to “preserve” the party.

So now these men lead their tattered party into the election with lies on their lips and a dual standard of morality in their hearts. They have one set of morals for churchgoing and for the children’s hour, and another for the smoke-filled rooms.

Nor is this the full extent of their dishonor. They have abandoned the one among them who had the courage to resign, Defense Minister Douglas Harkness, and left at the caucus door all the support and admiration which they gave him in the hour of his decision. And they have attempted to place the blame for their own failings on others. They have said that all the reports of revolt in the Cabinet are mere press speculation, utter newspaper fiction.2

One day ministers spoke in confidence to the press; the next they accused it of falsehood in reporting their unattributed stories. “We want no more of these treacherous confidences,” the editorial thundered. Ministers should be frank in admitting that the cabinet had been “in a turmoil, in a paralysis of indecision, for months. One of the basic problems of Mr. Diefenbaker’s leadership has been his preoccupation with treason. He has been so busy seeking out conspiracies and suspecting everyone he has had little time for anything else.” That was the reason for the prime minister’s inability to govern, and for the Globes call for his resignation. Now that ministers had failed “to re-examine and re-assert their ideals,” they stood before the electorate in the wreckage of their government. “The caucus settled nothing. The Prime Minister does not trust his Ministers; they do not trust him. There can be nothing among them now but more turmoil, backbiting and suspicion. Such is the sort of leadership they are asking the public to endorse.” This was the bitter public testimony of former friends. The Globe was challenging the dissident ministers to come clean.

Wallace McCutcheon had privately established the conditions of his loyalty. After the caucus meeting, where he had opposed a campaign based on attacking the Americans, he wrote to Diefenbaker.

You heard what I said this morning.

I do not retract from that and I assumed when you shook my hand when I stood up at Caucus and announced that I was going to the country with you that you accepted my position.

Lest there be any misunderstanding, I think I should now say that any statements which I regard as anti-American I will disassociate myself with publicly.

I am prepared to defend your defence policy – with which you know I agree only as a matter of Cabinet solidarity.

However, if the Secretary of State for External Affairs does not proceed expeditiously with the negotiations that you announced were under way then I will have to review my position.3

Eddie Goodman, too, had settled his conscience. On February 5, before the Commons vote, he had written to Diefenbaker tendering his resignation from the Ontario organization committee of the party. The job had taken a “crippling amount” of his time. “To these personal reasons for my desire to retire,” he wrote, “there is now added the overriding and decisive consideration which is our strong disagreement on what is the proper defence policy for Canada. My views in this matter are clear to you as we have discussed them at length during the past few weeks.”4 He expected his friend George Hees to leave cabinet as he had boasted he would, and was astounded to hear radio reports of the caucus reconciliation. Goodman and Edward Dunlop (Hees’s brother-in-law) flew at once to Ottawa and confronted the minister, who explained that he had been “swept away by the pleadings” of caucus and by Diefenbaker’s fresh, though vague, commitments. “The truth of the matter,” Goodman recalled, “was he’s a warm emotional fellow, and with everybody, all his friends in the caucus and people whom he’d worked with for all these years, pleading with him not to destroy the party, he gave in, which is easily understandable.” Goodman told him he “was an ass,” and left Hees stewing.5

For two days, as he reflected on the challenges from Goodman, Dunlop, John Bassett, and the Telegram and Globe editorials, Hees attended cabinet meetings preparing for the election campaign. Pierre Sévigny, too, had agonized over the nuclear conflict and Diefenbaker’s faltering leadership, but apparently expected to be promoted from associate minister to minister of defence after Harkness’s resignation. Diefenbaker made no move during the week of crisis. On Friday evening, Sévigny and Hees decided to offer their belated resignations the next morning, and to persuade Léon Balcer to join them – still vainly hoping that a walkout would persuade Diefenbaker to retire. Balcer was summoned from Three Rivers for another late-night discussion at Hees’s apartment, but he refused to resign. Early on Saturday morning, while the latest round of rumours busied the telephone lines to Sussex Drive, Hees and Sévigny arrived at the door carrying their letters of resignation. Diefenbaker was still upstairs in his dressing gown, so Burt Richardson led them to the library and chatted while the prime minister dressed.6 Diefenbaker made his brief record of the interview a few days later.

On Saturday my wife informed me about 9.15 a.m. as I was up in my room, that Hees and Sevigny had arrived. I said as they had not phoned this was rather surprising.

I dressed and came down to the library and they were both standing and both smiling.

Hees said: “I am here to reason.”

I said: “I am not going to listen.”

He laid his resignation on the little table.

Sevigny said: “I too will have to resign,” and then produced his.

I said: “Won’t you wait?” and they said “No,” so I said: “That is the end,” and they left me.7

Richardson thought that “the prime minister was thunderstruck. He took the resignations but he was practically speechless about this because it was so much of a surprise.” The ministers still in Ottawa for the weekend were summoned to Sussex Drive for the latest emergency consultations. About a dozen turned up, and they in turn used the telephones to seek assurances of loyalty from those who were absent. By lunchtime it seemed clear there would be no more resignations, and Diefenbaker agreed that the vacant posts should be filled at once.8

“Olive has had a very hard and trying time,” Diefenbaker wrote to his brother on February 8, “but there has never been anything but words of encouragement uttered by her.”9 He did not repeat to Elmer his earlier claim that she had counselled his resignation. Friends whose loyalties were personal and disinterested quickly rallied round. Helen Brunt telephoned and wrote:

A phone call is so unsatisfactory. My purpose in calling as in this note is simply to say that I have the utmost faith in Our Prime Minister. I know he is doing what he believes best for Canada. And who are we to know better, who do not know anything of the matters at hand.

Oh Olive I know the heartache when they hurt your man. It will heal but the scar is always there. And you know who your real friends are after it’s over…

…I’m glad Bill isn’t here. It would break his heart but then he would have been happy if he could have helped – whatever John did Bill went along with. They battled but if the P.M. was adamant Bill accepted it and that was the end.

If I can be of any help any time, call me. I will do anything anytime.10

Diefenbaker seemed genuinely puzzled by the cabinet defections. “We will … face the sniping that goes on from those who left,” he told Elmer. “I cannot understand Mr. Harkness. He agreed to the statement I made in the House of Commons on Defence, shook my hand after I delivered it, and then he went against me. Mr. Hees of course is another of those who through history reached out for the leadership too soon. He thought he was more powerful than he was. I did much for him but he continued to get himself into difficulties … It seems impossible to fathom the mentality of such as Harkness, Sevigny and Hees.” But he was determined to fight on: “Elections are not won except in the last week. I am the underdog now and that means that the fight must be strongly waged.”11 The role was familiar and liberating. It meant “hard work on the part of your supporters. Hard work spells victory.”12 Diefenbaker thought he could see beyond the Bassetts, the Dalgleishs, the Goodmans, the Heeses and Sévignys – those of little faith and ulterior purpose – to the voters who admired and rallied to the underdog, to those ordinary Canadians who understood his quest as his betrayers could not.

Besides, there were others still loyally committed to the cause. In January, when Allister Grosart gave up the national directorship of the party, Diefenbaker announced the appointment of Dalton Camp to replace him, with the mutually agreed title of chairman of the national organization committee. He was prepared to act without salary as Diefenbaker’s “personal representative to the organization at large,” because “I have for you a personal affection and simple loyalty that has, since you assumed the leadership … no reservations or limitations short of my personal mental and physical limits.” With an election bound to come soon, Camp reflected: “What is required, then, is fresh energy, enthusiasm and new direction to the organization. Enthusiasm must be rekindled, a tenacious will to win must become pervasive in the party. New techniques must be developed and applied and we obviously must [be] ready for battle. To all that, I offer to apply myself without stint or reservation and with optimism and confidence.”13 Camp, like Diefenbaker, enjoyed fighting the Grits. He reminded his leader that, since 1952, he had been involved in twenty-three federal and provincial election campaigns on behalf of the Tory party. Once the campaign had begun, he was rejoined in managing it by Allister Grosart.

On February 20 another prodigal returned. George Hogan – who had started the public phase of the party controversy over nuclear arms – wrote to Diefenbaker offering his full support in the election “both for the Party and for you personally.” He had not changed his mind about accepting nuclear weapons, but conceded that “we are in an election campaign and the alternatives are either to reject the Party’s whole programme because of one disagreement or to accept the whole programme in spite of one disagreement.” Since all parties were internally divided on the nuclear issue, he said, “I can see no reason why the Conservative Party should be called upon to suffer for its nuclear differences while the other parties are allowed to profit from theirs. As I see it, the essential difference between the Conservatives and the Liberals on this question is that while our approach is to adopt no policy until May, theirs is to adopt two policies until April.” He wished Diefenbaker success in the campaign.14 The new premier of Ontario, John Robarts, pledged his organization’s aid as well.

Despite this evidence of renewed support from members of the party in Toronto, Diefenbaker was determined to see his struggle from what was, for him, a traditional perspective. On the platform, he was fighting not only the Grits and the Kennedys but also his old antagonists “the Bay Street and St. James Street Tories” who had inspired “the desertions and insurrections” of the previous weeks.15 When he addressed a large joint meeting of the Empire and Canadian Clubs and the Toronto Board of Trade in mid-February, he joked that “Daniel in the lion’s den was an amateur performer compared to me.”16 And some of the enemy, he suspected, remained within. On February 11 he appointed Wallace McCutcheon to George Hees’s vacant portfolio of Trade and Commerce in the hope that he “might help to still some of the storms surrounding us” – and because “our circumstances had not allowed me the luxury of firing him.” But McCutcheon, he later wrote, “spent the entire election threatening to resign, with appropriate media fanfare, if I treated forthrightly the major issues of the campaign … I thought him the biggest political double-crosser I had ever known.”17

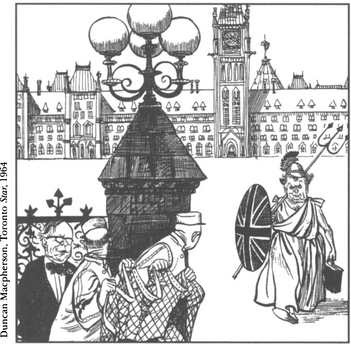

While McCutcheon cautioned Diefenbaker against an anti-American campaign, Newsweek magazine provided the prime minister with a safe target of attack for its February 18 cover feature on “Canada’s Diefenbaker: Decline and Fall.” Diefenbaker’s dark and scowling face, brows furrowed, lips pursed, jowls almost shaking, hair flying into the title line, dramatically lighted from below to emphasize every crease, landed on the newsstands in the first week of the Canadian campaign.18 Inside, the story described the political crisis for American readers in terms familiar to Canadians, but included a few tendentious sentences describing that extraordinary face on the cover.

Diefenbaker in full oratorical flight is a sight not soon to be forgotten: the India-rubber features twist and contort in grotesque and gargoyle-like grimaces; beneath the electric gray V of the hairline, the eyebrows beat up and down like bats’ wings; the agate-blue eyes blaze forth cold fire. Elderly female Tory supporters find Diefenbaker’s face rugged, kind, pleasant, and even soothing; his enemies insist that it is sufficient grounds for barring Tory rallies to children under sixteen.19

Dalton Camp seized the initiative by photocopying the Newsweek feature and sending it immediately to all Conservative constituency presidents. “Although the target of this derogatory tirade, the Prime Minister, has made no comment,” Camp wrote, “I believe the members of this organization will condemn it in the strongest terms. The article not only attacks the person of the Prime Minister, but the office as well, and is obviously calculated to overtly inflame public opinion. It is difficult to recall any American publication making a more abusive and inflammatory attack on the head of any state, friendly or otherwise.”20 The prime minister saw conspiracy at work. He told his audiences, and repeated the charge in his memoirs: “Who, among those who voted in 1963, will ever forget the Kennedy-conceived message conveyed to the Canadian electors by the cover and contents of the 18 February issue of Newsweek: its editor was President’s Kennedy’s close friend.”21 Ben Bradlee, it was true, was one of the president’s intimates, and Diefenbaker was not in Kennedy’s good books. But the notion that the cover article was “Kennedy-inspired” was no more than a hunch, an expression of Diefenbaker’s heightened sense that his enemies were uniting and closing in. If damage really was intended, Washington must have been disappointed. The mischievous cover picture probably assisted more than it harmed the Diefenbaker campaign. Diefenbaker’s response of theatrical indignation was both calculated and genuine, the reaction of a professional performer with a thin skin. His audiences could sense, and sympathize with, his anguish while they also relished the performance.

Publicly, the policy of the Kennedy administration was to remain strictly neutral after the flareup of January 30. It would not comment on the Canadian election. Privately, there was outspoken distaste for Diefenbaker in the White House and the State Department, which was echoed in dispatches to Washington from the American Embassy in Ottawa. In a long telegram on February 3 commenting on the consequences of the State Department press release, Walton Butterworth offered a withering assessment of the Canadian cabinet and its policies, and an encouraging prospect of better times ahead. Butterworth was in no mood for tempered judgment. For six years, he reported, the United States had tolerated Canadian “foot dragging” in continental defence and “pretentious posturing” in other areas of foreign policy, until “our sudden dose of cold water” produced an “immediate cry of shock and outrage.” But the “traditional psychopathic accusations of unwarranted US interference in domestic Canadian affairs” were rapidly subsiding as Canadians began to face the “hard realities, as set forth in the Departmental release.”

Preponderance of evidence available – news media, editorial comment, private citizens expressions of views – indicate shift of public attention from US statement to clear recognition Diefenbaker indecisiveness, with frequent and widespread reaffirmation of identity of US and Canadian interests and explicit acknowledgment that Canada has somehow gone astray. Department will recall this was basic aim of exercise … i.e. to bring Canadian thinking back to state of relevance to hard realities of world situation. Defense policy, particularly nuclear weapons issue, was key element this psychological problem, and its resolution will have profound bearing on Canadian attitude toward other less important foreign policy questions.

For past four or five years we have – doubtless correctly – tolerated essentially neurotic Canadian view of world and of Canadian role. We have done so in hope Canadians themselves would make gradual natural adjustment to more realistic understanding…

Inconclusive outcome last June’s general elections … fumbling and indecision during Cuban crisis, continued … evasiveness on vital defense matters suggested reappraisal necessary…

In effect we have now forced issue and outcome depends on basic common sense of Canadian electorate. Our faith in their good judgment is based on our reading that public has been way ahead of political leadership of all parties … In short we think Canadian public is with us, even though some liberal politicians have been afraid we have handed Diefenbaker an issue he can use against them and US. We think Canadians will no longer accept irresponsible nonsense which political leaders all parties, but particularly progressive-conservatives under Diefenbaker, have got away with for several years.

If our appraisal is sound and if trend continues, we face transitional period uncertainty, probably until general elections return a new government with an absolute majority and thus a clear mandate … World has changed and Canadian people know it. Polls show strong Canadian majority support for acquisition nuclear warheads and for close cooperation with us. Cuban crisis last October evoked widespread evidence public unhappiness with Foreign Minister Green’s moralizing and Diefenbaker’s flexible inaction…

We should not be unduly disturbed at steam of resentment which first blew off upon publication of Department’s release. Diefenbaker’s reaction was expected. He is undependable, unscrupulous political animal at bay and we are ones who boxed him in … Let us also face fact that we are forcing Pearson to go faster and further than he desires in the direction we favor … We have reached point where our relations must be based on something more solid than accommodation to neurotic Canadian view of us and world…

As this appraisal indicates, we see grounds for optimism that over the long run this exercise will prove to have been highly beneficial and will substantially advance our interests. We have introduced element of realism which no government, whether progressive-conservative or liberal, will be able to ignore.

One thing which could bring it all to naught would be backing away from our present stand … On maintenance of this stance depends framework of our future relations with Canada.22

Whether or not there was the conspiracy of forces that Diefenbaker saw in his darkest moments, or hinted at from the platform, there was no doubt that the Kennedy administration looked forward to a new Canadian government not led by John G. Diefenbaker. As the campaign opened, Washington kept its powder dry and watched events to the north with unusual care.

Butterworth reminded Washington on February 2 that the Rostow memorandum was still “hanging over our heads, and Diefenbaker or someone else may decide to try to make political hay of it at any time. It is probably a good thing that he doubtless knows that the Liberals are aware of his possession of it and the manner of his acquisition since, in essence, failure to return to such an invited guest a personal, confidential paper would be difficult for Diefenbaker to explain to the Canadian public.”23 Embassy officers reported discussion of the memorandum in their presence by Grattan O’Leary and the Liberal editor of the Winnipeg Free Press, Shane McKay, at the end of January, as evidence that its existence must have been fairly widely known.24 But Butterworth implied that if the memo was still hanging over Kennedy’s head, it was also hanging over Diefenbaker’s. The prime minister knew the risks of using it.

Before his second winter campaign could begin, Diefenbaker flew to London for three days in late February to be invested as an honorary freeman of the City of London, the first Canadian prime minister to receive this honour. He enjoyed the interlude as a brief escape from political turmoil, a soothing balm for his bruised ego – and a burst of glowing and uncritical publicity that could not have been better timed. On Sunday, February 23, he read the lesson at the City Temple, paid a short visit to Sir Winston Churchill, and met Harold Macmillan for the first time since the collapse of Britain’s negotiations to enter the Common Market. Next day, he and Olive rode in a royal landau, under escort by mounted outriders of the RCMP, to the Guildhall to receive the freedom of the city before an appreciative audience of 1100 guests. The Lord Mayor good-naturedly referred to Diefenbaker’s three Indian chieftainships in wishing him “the sharp eyes of the eagle, the wariness and strength of the walking buffalo, and the joyous speed and abandon of the many spotted horses” during the coming election campaign. Diefenbaker responded gratefully for “the greatest civic distinction to which any man or woman can aspire … To be of London is to share in a stream of history that has enriched a quarter of the world’s population within the Commonwealth and free men everywhere.” Afterwards, the Diefenbakers were honoured guests at a Mansion House banquet featuring nine wines. “He raised a glass to his lips to respond to the frequent toasts,” wrote Charles King of Southam Press, “but apparently enjoyed the hospitality less than other guests.” The party returned overnight to a chilly Ottawa dawn.25

“Somebody up there doesn’t like us”

The Chief had been unsettled by jokes and gossip about his strained appearance and shaking hands, and in a gesture reminiscent of Dwight Eisenhower’s 1956 campaign, he released a medical certificate at the end of February signed by two Toronto physicians testifying that he was in excellent health. “At no time,” they affirmed, “during this or at past examinations has there been evidence of any chronic illness.” The Winnipeg Free Press, among other papers, published a photograph of the medical certificate.26

“The 1963 election campaign,” Diefenbaker recalled, “was one of the more uplifting experiences of my life … There was no question that everyone was against me but the people, and that unless I could find a way to get the message across, I would be lost.”27 So – inspired by Harry Truman’s 1948 “Give ’em hell!” campaign – he decided to conduct a whistle-stop election, travelling as much as possible by train, stopping briefly at the little towns to mingle with the crowds that appeared in bitter cold to greet him. At Capreol, Ontario, on February 28, Diefenbaker spent twenty minutes on the station platform as the temperature hovered at −22F. When his train arrived in Prince Albert on March 2 – delayed by unscheduled stops at Hague, Rosthern, and Duck Lake – Diefenbaker descended to a home town welcome from the mayor and five hundred citizens. The more sedate and “prime ministerial” speaking style of 1962 was discarded for the evangelist’s tones of 1958, mingling nostalgia, scorn, and humour with hints of paradise and hellfire. The ridicule was mostly reserved for Mike Pearson and the Liberals, since Diefenbaker knew that Wallace McCutcheon and the State Department were measuring every speech for signs of excessive or provocative outbursts of anti-Americanism.28

The prime minister felt alone on the campaign trail – and most of the time he was alone. Davie Fulton had gone to British Columbia; Donald Fleming was not running, although he stayed in Ottawa to manage cabinet business until April 8; Douglas Harkness was running, but at odds with his leader; George Hees had retired and departed the country for the duration; Pierre Sévigny fought the election as an independent Conservative; Ernest Halpenny had retired; and other ministers were tied down in tight contests in their own constituencies.

As usual, Diefenbaker had one speech – with infinite variations of order, emphasis, and anecdote – for six weeks of campaigning. It was fully elaborated at his Prince Albert nominating meeting on March 2 before an audience of a thousand. He recalled elections from his youth at Fort Carlton, when candidates of both parties travelled together to speak from the same platform – and the occasion, perhaps apocryphal, when the Conservative fell ill and the Liberal delivered both speeches. (The story was familiar, so applause and laughter smothered the punch line.) He spoke to those in his audience “whose fathers and mothers came to this country, came here as pioneers, came here to build a Canada, came here to join with all the races of men. One of my reasons for being in public life and I’ve said it from the earliest days, was the opportunity to be able to do something in order to bring about in this nation without regard to racial origin, while preserving the constitutional rights of the initial and primary races of this country … equality of opportunity, to remove discrimination whatever one’s racial origin may be, to give to Canadians as a whole a pride of being Canadians, to remove that stigma that in the past existed that blood count constituted something in the nature of citizenship.”

In the last election, the Liberals had claimed that Canada “was on the road to ruin … They downgraded Canada. They undermined Canada. They did it deliberately in order to destroy.” In doing so, he said, they provoked the foreign exchange crisis that the Diefenbaker government had acted decisively to overcome. “And today Canada, as a result of our action, has the largest foreign exchange amount it has ever had in the history of this nation.” His government had enriched prairie farmers by selling grain to China on credit, and China had repaid its debts on time.

Diefenbaker explained his defence policy as one that changed to suit rapidly changing circumstances. Why should he be criticized for that when Britain and the United States followed the same shifting policy? When Canada agreed to accept two Bomarc missile units, the United States planned to build thirty or forty launching sites to protect their Strategic Air Command bases. Now there were only six: two in Canada and four in the United States.

We thought at the time the Bomarc was established, was set, that we’d meet the problem of the bomber. However, more and more it’s becoming known and apparent that such a system is no longer effective.

The people of Canada are being fooled, or an attempt is being made to fool them, by the Opposition…

And the other day, the other day, the Secretary of Defense of the United States, Mr. McNamara, said, well, we’re keeping these Bomarcs, in effect not because they are any good, but after all, we paid for them. Ah … I wonder why it is these facts are concealed from the people. Mr. Pearson says: Well, we have commitments. I say to him, there are no commitments that this Government has failed to carry out. Agreements entered into when one state of fact exists, are they to be maintained regardless of changing conditions?

What did Mr. Pearson say? He said – Oh… I wish the Government would be consistent. These are his words, and I am quoting you. “In my view we should get out of the whole Bomarc operation.” That’s two years and a half ago. “The Bomarc operation … not only do we not think it is an effective weapon; our objection is the kind of defense it is, that kind of defense strategy it represents which we do not think will be effective, however effective the weapon may be.” Work that out; play that on your ukulele!

First he says it is no good, and then he says however good it is and however effective, we don’t believe in it. And then he went on to say this – just like in the old crown and anchor game, you pay your money and you take your choice. (Laughter) All right…(laughter). “If the United States wishes to continue that kind of protection with the Bomarc, let the United States do so and let us withdraw from that kind of continental defense.” Now he says, “Canadians, we never break our commitments.” I agree with that. We never have…

This is another one. I simply use his quotations to support the stand that we have consistently taken…

…“The Ottawa Government should end its evasion of responsibility by discharging its commitments. It can only do this by accepting nuclear warheads.” Well, he told us all the time not to do that … Then he really came out with one…“You can only do this by accepting nuclear warheads,” I said to myself, that sentence can’t finish there. Because I know him. (Laughter.) I know him…“We would accept them. Then having accepted them, we would re-examine at once the whole basis of the Canadian defense policy so as to make it more realistic and effective for Canada than the present one.” (Laughter.)

…They shouldn’t be playing politics such as Mr. Pearson’s been playing with an issue such as that, that affects the lives, the hopes, and the future of mankind. (Applause.)

That’s the view we take … We’re going to set out in detail at the earliest opportunity this whole question in simple form…

Insofar as Canadian soil is concerned, I set this forth before and I again set it forth. We shall place ourselves in a position, by agreement with the United States, so that if war does come, or emergency takes place, we shall have available to us readily accessible nuclear weapons. But in the meantime we shall not have Canada used as a storage dump for nuclear weapons. (Applause … Hear! Hear!)29

If the government’s policy was confusing, Diefenbaker had demonstrated – to the delight of his partisan audience – that the Liberal policy was equally if not more confusing. Both Diefenbaker and Pearson were hapless dancing puppets in this game. The grand folly of nuclear deterrence meant, for Canada, a defence that could be no defence, and a policy that defied logic. There was no more sense to be made of it.

Diefenbaker disposed easily of Robert Thompson. The Social Credit leader, he suggested, wanted to get rid of him because Thompson knew there were no Social Credit votes in the west as long as he remained prime minister.

Diefenbaker was exhilarated by the fight. “You know,” he told his Prince Albert audience, “in nineteen hundred and forty-eight they said of Harry Truman, he had no chance in the election. All the press said that, or at least 90%. All the Gallup polls said that. Only one person believed that Harry Truman would win and that was his wife. I have my wife and an awful lot of others across Canada!”30 As his train arrived in Winnipeg, the Free Press reported that the prime minister’s weekend in Saskatchewan had been “a tonic” for him. “The two days of uncritical acclaim from the people in ‘small-town Saskatchewan’ unquestionably has strengthened him for the campaign which he gets underway in earnest in a Winnipeg rally tonight.”31

Only four major newspapers supported the Conservatives in 1963: the Ottawa Journal, the Winnipeg Tribune, the Victoria Colonist, and Beaverbrook’s Fredericton Gleaner. But as Diefenbaker moved slowly through the small towns to rallies in the big cities, he grew more and more convinced that “the people” were indeed on his side. The crowds were big and enthusiastic and laughing with him. Mike Pearson and his team – despite their appearance of solidity and efficiency, and the promise of an activist government and reconciliation with the United States – could not ignite the same passions. And in mid-March they made a damaging error. Diefenbaker put it down to “the Liberal high command,” who “seemed to mistake our country for the United States”:

Their Madison Avenue techniques came a cropper with their colouring books, white pigeons that flew off never to be seen again, and that never-to-be-forgotten “truth squad.” Poor Judy LaMarsh! I had much fun with her in Moncton and Halifax. She had a specially designated table right down at the front of the hall so she could hear everything. Although the people thought she was a great joke, they also were offended by the impudence of those who had sent her to challenge the truth of my every statement. The Liberals quickly got the message and ended the Truth Squad in two days. Had they kept her on, however, we might well have picked up several extra constituencies.32

For Diefenbaker, mistaking Canada for the United States meant introducing too-slick electoral techniques, turning politics into a professionally managed game, and paying more attention to opinion in the big cities and the Oval Office than in Duck Lake. The Chief himself, as a keen student of American electoral politics, had made his own contributions in earlier years to the shift in campaign techniques, and this time he had no hesitation in comparing himself to Abraham Lincoln and Harry Truman. His real objection was not to American models and American influences, but to American influences of a certain kind: too much eastern sophistication, too much comfort with power, too many displays of arrogance, too close an association with the Kennedys and the eastern liberal establishment. The trouble for him was – as the polls showed – that John Kennedy was a real and powerful competitor for the allegiance of Canadians, and the beneficiary in this election was bound to be the Liberal Party.33

But Diefenbaker’s emotional campaign, coupled with the general confusion about nuclear weapons and the American relationship, had stopped the Liberals cold. Their support in the polls fell, while Conservative strength held steady and Créditiste sentiment grew in rural Quebec.34 Liberal expectations of a parliamentary majority faded. In desperation, Keith Davey and Walter Gordon persuaded Pearson to promise that a new Liberal government would begin its term with “sixty days of decision.” Pearson was worn out, ill, and depressed, and by the end of March he wondered whether he could finish the campaign.35 Diefenbaker gained renewal in his own exhausting journeys, soaking up strength from his audiences as he played endlessly on his simple themes.

President Kennedy did not want to assist Diefenbaker’s re-election, but in what Theodore Draper described as “the almost chaotic state of the leadership circles in Washington,” the right hand often did not know what the left hand was doing. At the end of March, the US Defense Department offered Diefenbaker a gift by releasing the transcript of secret testimony that Defense Secretary McNamara had given earlier in the month to the House Appropriations Subcommittee. In it, McNamara imprudently declared that the remaining Bomarc missile sites were expensive and ineffective, but once established, could be maintained at little cost. “At the very least,” he testified, “they could cause the Soviets to target missiles against them and thereby increase their missile requirements or draw missiles onto these Bomarc targets that would otherwise be available for other targets.” Too late, the White House ordered a clarification explaining that the statement did not refer to the two dispersed Canadian sites – but the damage was done. Diefenbaker pounced: “The Liberal party would have us put nuclear warheads on something that’s hardly worth scrapping. What’s it for? To attract the fire of the intercontinental missiles. North Bay – knocked out. La Macaza – knocked out. Never, never, never, never has there been a revelation equal to this. The whole bottom fell out of the Liberal program today. The Liberal policy is to make Canada a decoy for intercontinental missiles.”36

While the White House sought to maintain its public show of neutrality throughout the Canadian election, Kennedy could not restrain his private feelings. After the January 30 press release, Pearson remained fearful that another ill-considered effort to help him might backfire, and his fears were well founded. In late March, while Pearson was addressing a Canadian Legion meeting in Edmonton, he received a message on the platform that there was a telephone call for him from the White House. Pearson’s press spokesman Richard O’Hagan called back on the janitor’s telephone to discover that the messenger was Max Freedman, the Washington correspondent of the Winnipeg Free Press and a close friend of the president. He had just had a private dinner with Kennedy, and he insisted that he must speak to Pearson. O’Hagan brought the demand onstage to Pearson. Knowlton Nash recounts the story:

Mystified and alarmed, knowing what Diefenbaker might do with such information, Pearson followed the janitor to a basement office. Nervously, he picked up the phone. They spoke for fifteen minutes, with Freedman enjoying his role as middleman between Kennedy and Pearson, passing on the highlights of his conversation with the president that night and some of Kennedy’s suggestions. “For God’s sake, tell the president not to say anything,” Pearson said. “I don’t want any help from him. This would be awful.”…

“This was a narrow escape,” Pearson later said, “since I knew there were people abroad in this land who would … insist that it was a deep dark American plot to take over the country via Pearson and the Liberals. To my relief, it never was reported; the janitor said nothing about the call.”37

With Pearson’s fresh warning (and the McNamara testimony) in mind, Kennedy’s national security adviser McGeorge Bundy took renewed precautions on April 1 in a memorandum to the secretary of state and the secretary of defense:

During this climactic week of the Canadian election campaign it is likely that intensified efforts will be made to implicate the United States in one way or another, especially by accusing us of trying to influence the outcome. The President wishes to avoid any appearance of interference, even by responding to what may appear to be untruthful, distorted, or unethical statements or actions.

Will you, therefore, please insure that no one in your Departments, in Washington or in the field, says anything publicly about Canada until after the election without first clearing with the White House. This applies to all contacts with the press regardless of the degree of non-attribution.38

Bundy must have been thinking of at least two provocative incidents. One concerned the suspicious opening of an American diplomatic pouch in the Ottawa post office.39 The other involved that familiar hot potato, the Rostow memorandum. On March 27 Charles Lynch of Southam Press reported in the Vancouver Province and the Ottawa Citizen that Prime Minister Diefenbaker had in his possession an uncomplimentary presidential briefing document from President Kennedy’s 1961 visit to Ottawa.40 By the time the Citizen used the story, two paragraphs had been added quoting Diefenbaker in Kelowna, British Columbia, as saying that the story was “completely false … I don’t know where that story came from … I have to repudiate it.”41 The State Department informed the American Embassy in Ottawa that it should respond to inquiries with a standard line: “We do not intend to comment on any speculative newspaper stories during a Canadian election campaign,” but it was watching every move with care.42

On April 1 Lynch published a second story on the document, indicating that Diefenbaker had confirmed its existence. “Sources” added that he was unlikely to use it in the closing days of the election campaign. On the White House copy of this report, there is a handwritten note to McGeorge Bundy: “Pretty clear use of the ‘push’ document without ‘using’ it.”43 That view was confirmed in a dispatch from Butterworth the next day, reporting that Lynch had indicated that his source was Diefenbaker himself.44 Butterworth wondered why there had been no editorial comment in Canada, and concluded that “this is simply too hot a story to handle since it involves question good faith in personal relations between Canadian Prime Minister and Chief of State of Canada’s major ally.” As a result, the public had been left with an impression that there had been an American threat to “bring economic pressure on Canada in effort get nuclear warheads on Canadian soil. Moreover no one has publicly asked why … there has not been explanation how document acquired or why it was not promptly returned. We are now getting worst of both worlds.”

The State Department commented to Bundy that Butterworth wanted consideration of an American response. But State’s inclination was to do nothing “unless Mr. Diefenbaker makes use of it in the next three days.” Any American statement “would have to be very carefully weighed at the highest level, since any action would cause a sensation in Canada, with unpredictable results.”45 Over the next few days the White House considered several possibilities: publication of the full document, continuing refusal to comment, or a conditional “no comment at this time,” which might imply a clarification after the election. Bundy’s White House aide considered that Diefenbaker’s most likely move on his “crooked path” would be to make selective references to part of the document on the evening of Friday, April 5. They would likely be sufficiently misleading to confirm the impression that the memo referred to pressures on Canada to accept nuclear weapons for storage. To respond in time, Washington would have to intervene before the Saturday morning newspapers went to press. The “tentatively agreed policy of this government” was to release the document from the White House “with a very brief comment designed to note in low key the unethical conduct of the Canadian Government in retaining and then disclosing the document,” but the author urged instead a policy of “no comment at this time.” Even a “gently chiding” release might be counterproductive in Canada, while a temporary “no comment” would confirm American neutrality in the election and also create “an air of mystery, as though we had a load of dynamite which we could easily detonate if we were not so determined to stay out of the campaign, especially in its closing hours.”46 By this time all the variations on Washington’s “non-intervention” were being weighed as forms of intervention, calculated not to assist Diefenbaker and not to harm Pearson. For the moment, the White House simply waited.

Diefenbaker made no mention of the document on April 5, but by Saturday morning the story was blossoming. Peter Trueman of the Montreal Star and George Bain of the Toronto Globe and Mail both reported from Washington that the document had been written by Walt Rostow for the president and that it “contained at least one pencilled notation in the margin in the president’s own hand.” Bain identified the comment as: “What are we to say to the … on this point?” while Trueman quoted the words as: “What do we do with the … now?” (Both papers politely excised the epithet.) Bain said that the document contained no threats, and that “the Canadian government’s purpose in retaining the document seems to have been to use it as a diplomatic lever.” Washington’s complaint was that there had been “a serious breach of diplomatic courtesy … in making use of a mislaid private document.” The existence of the memorandum, he said, “did enter into diplomatic communications, perhaps through the United States ambassador having been informed.”47

After these reports, the White House adopted another line of response: selective but full confidential briefings for a few correspondents, but no public statements. The first result was a dispatch by the New York Times’s James Reston, published in the Montreal Star (but not in the Times) on election day, April 8. It reported that Washington “is full of rumors that the prime minister’s staff has been using a secret United States document as an instrument in his campaign for re-election.” Reston said that a Washington Post reporter had told his paper that the missing phrase from Saturday’s stories (supposedly in the president’s handwriting) was “S.O.B.” But “the report of Presidential anger seems to most observers here to be unlikely,” since Washington’s annoyance with Diefenbaker had arisen only recently over the issue of nuclear arms. That subject “was not in controversy then.” “Besides,” Reston added, “if anybody in Canada can read President Kennedy’s handwriting, it is more than anybody in Washington has been able to do. In this city, most people find it almost impossible even to decipher his signature.” What was true was that “Canadian-American relations have been poisoned by one incident after another.” And “the very fact that Mr. Diefenbaker could have threatened to use the working paper in the 1962 election has inevitably entered into estimates here of the working relations between the two governments.” Diefenbaker’s office had refused to comment to the New York Times about any marginal comments on the memo by the president. In Washington, Reston judged, there was only one general conclusion: “The document should, as a matter of diplomatic courtesy, have been returned to the State Department.”48

In the end, it seemed, the prime minister’s surreptitious use of the Rostow memorandum in the last week of the election campaign was of no noticeable benefit to him. Washington, in its response by proxy, managed to make its effective point that Diefenbaker was the one who had committed the diplomatic offence. For those who noticed, the contretemps probably served to harden existing political commitments, both for and against the prime minister. He was either a courageous white knight or a blackguard. And Kennedy had not used the expletive deleted.49

On the last weekend of the campaign another unusual incident caused disturbance for Walton Butterworth and Mike Pearson, but it came too late to make any impact on the vote. On April 6 the Vancouver Sun published a story by the Southam reporter Bruce Phillips suggesting that “the Conservatives have a document so hot even they are afraid to use it, a document purporting to be a letter from American Ambassador Walton Butterworth to Liberal chieftain Pearson telling him the Conservatives are unfit to govern Canada.” The party, Phillips said, had had the letter for “about two weeks,” but had been “uneasy about using it because they did not know where the splinters would hit when the explosion came.” The letter, dated January 14, offered congratulations to Pearson for his speech advocating the acceptance of nuclear warheads for Canadian weapons. Butterworth, he said, had learned of the existence of the letter and had called the cabinet secretary, Robert Bryce, to deny having written it. Pearson, too, vehemently denied its authenticity. Phillips reported that the letter “came into the hands” of George Drew in London, who forwarded it to Canada, but he explained nothing more about its provenance.50 The case looked suspiciously like that of the Rostow memorandum. Had the government provided this document, too, to a friendly reporter for use without attribution?

What made the incident more outrageous for Butterworth was that the letter was a forgery. Using it was a kind of dirty trick unfamiliar in Canadian politics or in the recent history of Canadian-American relations. Butterworth asked the State Department to pursue the issue with Canada, but in the aftermath of the election, Washington decided to let the matter rest “and hopefully disappear with other flotsam and jetsam cast up by the campaign.” Butterworth accepted the decision but protested to the State Department that it was mistaken: “What concerns me … is lest this be an indication that the Department is reverting to its old ways of treating Canada like a problem child for whom there was always at the ready a cheek for the turning … I do hope that in future we will deal with Canada with considered care and courtesy but in a more normal, matter-of-fact manner, and with due regard to the importance of obtaining quids for quos.”51

Diefenbaker’s account of the incident was disingenuous. Afterwards, in the memoirs, he wrote as though the letter had not been used in the campaign, and regretted that “not using it constituted a major political error.” He claimed to have “confidential knowledge, which will be revealed in due course, that it was a true copy,” but there appears to be no documentary evidence for the claim. Diefenbaker reproduced the entire letter in the memoirs and noted that after receiving it in late March he consulted Howard Green and Gordon Churchill about establishing its authenticity. Since there was no time to establish whether or not it was a forgery, he reported an honourable decision not to use it.52

The record, all of it available to Diefenbaker, looks less edifying. The letter, in photostat and postmarked March 20, 1963, was originally mailed to George Drew in London from an English address. Drew called Grattan O’Leary to warn him he had a “hot document,” and dispatched it that day to Diefenbaker. Soon afterwards the prime minister met O’Leary and urged him to publish it in the Ottawa Journal. Drew had warned Diefenbaker that the letter “could be of vital importance if its authenticity were verified, and it could be extremely dangerous if by any chance it is an attempt to plant something which could obviously boomerang very badly.” O’Leary thought it was a forgery and refused to publish it; Camp shared his scepticism. Diefenbaker kept the letter and discussed it with Allister Grosart, who passed on the story to the publisher of the Winnipeg Tribune, Ross Munro. Munro called Butterworth, who called Bryce to make his denial. And Bryce relayed the report back to Diefenbaker on his campaign train in western Canada.

Meanwhile, Diefenbaker had brought Howard Green and Gordon Churchill into his secret. He proposed to Green that he should return to Ottawa to “call in the Ambassador and ask him who wrote the letter. Howard was disturbed by the suggestion. I then suggested that he secure examples of signatures of the Ambassador, to which he replied that that would arouse suspicion.” Another dead end. Diefenbaker “thus turned the investigation over” to Gordon Churchill. Formally, Diefenbaker had taken his distance. What followed was publication in a small Manitoba newspaper, from which Bruce Phillips picked up the story for Southam News.

Later the RCMP examined the copy and determined that there were no typewriters in Butterworth’s office to match the one used in the letter. There were other anomalies, too. Diefenbaker believed that the RCMP commissioner had given Butterworth sufficient notice of his search to remove the incriminating machine, and he continued to insist that the letter was genuine. The point of this insistence, in face of the evidence, is obscure, unless Diefenbaker felt an unacknowledged responsibility for use of the letter – and an inability to admit he could have been wrong.53

The Diefenbakers returned as usual to home ground in Prince Albert for election day, while the Pearsons remained in Ottawa. As the count moved westwards that evening, Liberal hopes for a majority were raised and then lowered. Newfoundland delivered all seven of its seats to Pearson, but Diefenbaker held his ground in the Maritime provinces. In Quebec the Créditistes retained twenty seats, while the Liberals gained only twelve and the Conservatives lost six. In Ontario the Liberals picked up eight ridings from the Tories – not an overwhelming shift. At the Manitoba border Pearson had 119 seats (only thirteen short of an absolute majority), but there his bandwagon stalled. In seventy western and northern races, he won only ten, while Diefenbaker took forty-seven (for a loss of only two seats). At the final count Diefenbaker had 95 seats to Pearson’s 129. Social Credit and the NDP held the balance, with twenty-four and nineteen seats, respectively. The Liberal Party had consolidated its strength in the cities, while Diefenbaker’s Tory party settled more firmly into its rural and western strongholds. Only Quebec broke the national pattern, where Social Credit lost some areas of rural strength but achieved 15 percent infiltration into Montreal in several working-class neighbourhoods.54

Diefenbaker told a television interviewer on election night that the result reminded him of 1925, when Prime Minister King had lost by a plurality to Arthur Meighen’s Conservatives, but “had decided, as was his right, to meet Parliament on the basis that no party had a majority.”55 That seemed only a bit of mischievous talk designed to keep the Liberals on edge. By the next day Churchill, Hamilton, Grosart, McCutcheon, Frost, and others were urging the government’s resignation, and Diefenbaker accepted the choice. He was ready to face the Liberals as opposition leader, and nursed his resentments for later use. As he prepared for his flight to Ottawa on April 10, he told a Saskatchewan friend: “I went down there to see what I could do for the common people and the big people finished me – the most powerful interests.” But he made no public statement about his intentions, beyond indicating that he would “watch eventualities.”56

On April 12, in mysterious circumstances, six Créditiste MPs delivered a sworn affidavit to the governor general and to Mike Pearson declaring that the Liberal Party had the right to form the next government and promising their voting support to that government. Pearson had his absolute majority. Diefenbaker concluded that “there were no further eventualities for me to wait upon,” and arranged to meet Pearson to agree upon the transfer of power. At noon on Monday, April 22, John G. Diefenbaker was succeeded as prime minister by Lester Bowles Pearson.57

FOR THE NEXT FEW WEEKS JOHN AND OLIVE WERE PREOCCUPIED WITH THE MOVE from 24 Sussex Drive to Stornoway, the house provided for the leader of the opposition, taking two of their household staff with them. On the evening before their move, Diefenbaker told his brother, “Olive made a discovery. We thought we had emptied every drawer and for some reason she looked at the desk in my room on which the TV was placed and found two extra drawers in the back of the desk which I had completely forgotten about which revealed quite a number of letters which would not have been fitting for our successors to read.”58 The move was trying. Diefenbaker wrote: “I am hoping we can go West because there is quite a bit of furniture that should be shipped down here as ‘Stornoway’ is anything but equipped. We have had to buy a washing machine, dryer and all the kitchen equipment and there will be about $1000.00 in odds and ends of furniture that we will have to purchase. The only room that is properly equipped is my office and library which Olive has fixed up most attractively … It is almost six years since I had my hands on the wheel of a car so I will have to take some lessons before I get a license. I simply can’t exist by depending on taxis.” Within a few weeks, Olive had taken her driving test and acquired a licence, “so we will be able to get around a lot easier than we have since moving,” but in July “she was fortunate that she wasn’t injured when the car went over the sidewalk into a plate glass window. She was very calm about it.” Subsequently, the Diefenbakers were provided with a chauffeur, who took delivery of their new Buick Wildcat from General Motors in Oshawa on October 4. “It is a Canadian-made car,” John told Elmer, “and while we would have preferred a better Buick felt that we must not purchase a car manufactured outside Canada.”59

The Diefenbakers returned from a short trip to Saskatoon and Prince Albert in mid-May to find their surroundings more comfortable. “While we were away,” John wrote, “the staff at the house worked very hard and got everything in readiness. As soon as some of the furnishings that we had shipped from Prince Albert arrive here it will become very homelike.” Ten days later he was still adjusting to the life of an ordinary citizen: “Olive is still working on the house. Some of the furniture came from Prince Albert although the cost was very high. The freight on the bedroom suite was $400.00 and the cost of moving from 24 Sussex to our present address was over $650. A third-rate plumber did some work for us and charged us at the rate of $4.50 per hour. All these charges are far beyond anything that could have been imagined a few years ago.” Diefenbaker paid them out of his own pocket.60

The adjustment of routine was substantial but less trying. “It is far less work being Leader of the Opposition than Prime Minister,” he wrote on May 24, “and I am getting a great deal of rest and also more reading done than has been possible.”61 Diefenbaker observed the NATO ministerial meeting in Ottawa in May with resentment. “We invited them but the new Government does the entertaining and is receiving the applause. Lord Home went out of his way yesterday to build up Mr. Pearson by saying, in effect, that he became Prime Minister because he wanted Canada to be a good ally. Several of my colleagues are most annoyed at this because I refrained at all times from making political speeches in London that would criticize the Government or assist the Opposition.”62

As the new Pearson government adjusted to office, settled its commitment to take nuclear warheads for Canadian weapons, appointed the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, stumbled through its first budget debate, and confronted a disturbing wave of terrorist bombings in Montreal, Diefenbaker was preoccupied with his own position in the party and the country. Pearson regarded his opponent with distaste: “There is certainly going to be lots of unpleasantness in the House,” he wrote to his son on May 26. “D. is very nasty and cannot conceal his frustrations. He misses the pomp and prestige of office greatly and obviously.”63 Diefenbaker’s former newspaper supporters kept up their complaints. At the end of May he told Elmer: “The ‘Globe & Mail’ and ‘Telegram,’ and to a lesser extent until today, the ‘Gazette,’ are spending their time in personal criticism, for certain of the big interests have determined that there must be a change of the leadership of the Conservative Party.” Diefenbaker saw this criticism as a continuation of the winter conspiracy: “It is more than a coincidence that Davie Fulton was here on Monday and this is the third time that such a visit has been followed by an article by Arthur Blakely. However, I have got no intention whatsoever of falling in line with their plans and schemes. They should have learned that many years ago.”64 A week later he reported further: “Dave Walker gave a dinner on Wednesday night for the Conservative members of the Senate and the House of Commons and he made a typically frank speech except he told them they would not have been there if it had not been for me, much to my embarrassment. However, when speaking I pointed out that I had no intention of falling in line with the desires of the Liberal Party to get me out of the leadership with an assist from a few of my former colleagues.”65

During the next six months there were frequent calls in the party – centred in Ontario and Quebec – for a leadership review. Diefenbaker put them down at first to the inspiration of Davie Fulton who, he believed, “is doing his best to bring about a Convention – under cover work by him always seems to come to light! “Just before a meeting of the Conservative executive in October, Diefenbaker received reports that George Hees’s aide, Mel Jack, was coordinating efforts to remove him from the leadership by the spring of 1964, while “Fulton and his people” continued their activities. “I am more definitely set than ever before against resigning no matter what they may do,” he told Elmer. “It is going to be a big fight and when these great and powerful financial interests determine a course of action they exert a tremendous influence. I beat them before and intend to do so again.” In November the Chief commented publicly that “you don’t have leadership conventions unless there is a vacancy. I am the leader and there is no vacancy.” Within the organization, he strengthened his own position by installing Gordon Churchill as national director and the former MP Richard Thrasher as national secretary.66

Dalton Camp told the party executive in October: “I supported the Conservative Party and its Leader, Mr. Diefenbaker, because I believed them to be right in all the issues vital to the country. Indeed, the greater the issue, the more right they were. Far from apologizing for my personal stand, I exult in it. In fact, I celebrate it with each passing day.” The leader had distinguished himself in the campaign. “Men in adversity do not always react the same. Thus, one of the prime qualities of leadership is personal courage. Those of us who saw Mr. Diefenbaker at close range during the campaign could not help but admire his courage, and could not help but be inspired by it. From the time he set out, we at Headquarters heard from him neither complaint, nor criticism, nor any discouragement. Even had he been wrong in what he stood for, it would have been a distinct privilege to have been associated with such courage.”

Now Camp declared that the party, “singularly blessed by the remarkable incompetence of those who succeeded us in office,” must seize its chances. That meant, paradoxically, engaging in “free expression and fresh thought within the Party itself … In the process of making a god of our Leader, we made sheep of ourselves … A healthy candor and a free exchange of thoughts are needed – should be encouraged – and must, in my opinion, be the purging influence resolving our present unresolved business. But I am not prepared to listen to those who would speak on Friday and leave us on Saturday, unless we do as we’re told.” This was a call to the faithful as skilfully ambiguous as one from Diefenbaker himself. The Chief took particular note of one paragraph, in which Camp called on the executive “to reunite this Party in mind and spirit. Surely, there must be more inviting targets on which to fix our aim than on one another. I would rather fight Grits than Tories … it is only self-inflicted wounds that are slow to heal and that can be mortal.”67

For two weeks in September Olive and John travelled to Italy, Egypt, and Israel, with brief stopovers in Greece and Switzerland, enjoying the privileges of an elder statesman and opposition leader. They were accompanied by Diefenbaker’s Commons colleague and physician, Dr P.B. Rynard. The trip was refreshing, and the leader returned to Ottawa for the reopening of parliament determined to confront both Liberal and Conservative opponents. Two provincial elections offered him mixed signals about the state of the party. In Ontario, John Robarts’s Conservatives received an overwhelming mandate despite the active participation of federal Liberal ministers in the campaign, while in British Columbia Davie Fulton’s Tories faced what Diefenbaker called “a frightful defeat” at the hands of W.A.C. Bennett’s Social Credit Party, winning no seats and only 11 percent of the popular vote. In Diefenbaker’s view that left Fulton with idle hands, which he would undoubtedly turn to the fight against the federal party leader. Diefenbaker thought he could handle that. The Ontario result, along with his own large correspondence, gave him hope that there was “a widely felt antagonism” to the Pearson government. The Chief planned to recommence war on two fronts, with speaking engagements across the country leading up to the annual meeting of the party in Ottawa in January 1964.68

At the end of October, Peter C. Newman’s book Renegade in Power: The Diefenbaker Years was published to widespread publicity and immediately became a bestseller. Diefenbaker denied having read it, but told Elmer on October 31 that the book was “a terrible piece of muckraking and slander. I am considering commencing action for libel. It is full of falsehoods. I am told that some wealthy people in high places provided the finances for its publication and there is some evidence to support this fact.”69 Two advisers provided him with commentaries on the book, both emphasizing the inappropriate depiction of Diefenbaker as a “renegade” – by definition, “one who has deserted party or principles.” “In the case of the Right Honourable Leader of the Opposition,” one declared, “his principles have followed a strong, clear line from his first entry into politics until now. There has been no deviation. The title is part of the Liberal Party policy followed in the case of every Conservative Leader, of character assassination.” But the other saw advantage in the name: “The book publishers – McClelland and Stewart – have added the title for box office purposes … As ‘renegade’ is a fighting word, the Conservatives will get all the benefit from having their supporters worked up to anger. In short, John Diefenbaker will enjoy a fresh windfall of sympathy votes … The immediate advantage to the Conservative Party is that Newman’s book has brought John Diefenbaker to front page attention on a scale far beyond anything that could be contrived.” The critic noted that – although the book contained “pure inventions of the kind dreamed up in after-hours drinking in the press gallery” – it portrayed Diefenbaker as “an extremely human person, a vivid and alive personality, and the recognizable hero of the Canadian scene.” The story made him “the true Alger-series hero – poor, decent origins; family long associated with Canadian history; lost in the blizzard with Uncle Ed!…it is the legendary material that will get into the school books of future generations of Canadians.” The legislative record was impressive, and the claim that Diefenbaker was indecisive merely showed that Newman “does not understand the process of decision in a parliamentary democracy.” The public, the commentator thought, would absorb the legend and reject the author’s bias; the book was based on “hearsay and guesswork, and … backstairs gossip”; its claims were unsubstantiated.70

Diefenbaker, too, was offended by the title. “Never has such an epithet been used in connection with one who has occupied the position of Prime Minister,” he wrote in his random speech notes. “I leave the judgement of my course and my actions to the Canadian people. They will decide – you will decide whether that epithet ‘renegade’ is one that can fittingly be applied to one who has devoted his life without thought of reward to the service of this country. Like George Washington I say that my only regret is that I have only one life to give to my country. But my reputation I have always preserved intact … Sometimes these things hurt.”71 Elmer comforted him with lashing insults against Newman, and reported that he was spreading the word against the author. While visiting the University Hospital in Saskatoon, he had told a woman who wanted the book that it was “published by the Liberal Party as vile propaganda and the proceeds are to be used as campaign funds for the Liberal Party. I don’t want you to waste your money.” The woman had replied: “I am so glad you told me that.” Elmer judged that “a person might as well fight back all the way.” A week later he added: “We’ll have to see that a decent book is written in your favor. I have quite a few notes – I jot them down when I think about them. These notes are not in order, but when I get them to-gether, I’ll send you some more material.”72

Diefenbaker consulted David Walker about whether he might have a case for libel, but decided instead to maintain his public silence and let his friends fight the battle of publicity. He was most satisfied by Michael Wardell’s long “Reply to Newman” in the Fredericton Daily Gleaner. “The book is a sparkling affair that is already a best seller, and deservedly,” wrote Wardell, “but it seems, in a way, an exercise in schizophrenia. Between the first part of the book and the rest of it there is a marked disconnection of thought and expression. The first part is a masterful historical summary of the formative years of Diefenbaker, from his beginnings as a small-town lawyer … to his becoming Prime Minister of Canada in 1957. The remainder of the book is a tirade of denunciation, execration and scarification. There are no contrasts of lights and shades; only bitter unrelieved black … The result is so patently biased, so unfair, and so reckless as to defeat its own ends, and bring sympathy to the subject rather than censure.” Wardell shared the Chief’s conviction that reporters, including Newman, and the CBC had seen the Conservative government through the eyes of the Liberal Party, and had thus been engaged, in Newman’s words, in “an unpatriotic conspiracy, probably Liberal-inspired.” Despite them all, Diefenbaker’s policies had proved to be “good, solid, common sense.” Wardell concluded with a call for loyalty: “If I were a Conservative politician, which I am not, I would stake my faith in Diefenbaker. I would expel the traitors from my Party, I would turn my back on the faint hearts, and I would go forward with my trust in the only man who can hope to lead my Party to victory. And I would bring these great issues to the test next spring.”73

Renegade in Power was the first and most successful of a new Canadian genre, the journalist’s dramatic summary of a political era. As much as anything Diefenbaker himself could do, the book helped to create the legend of a Canadian folk hero.

George Grant gave philosophic weight to the Diefenbaker legend when he published his Lament for a Nation: The Defeat of Canadian Nationalism in the spring of 1965. In counterpoint to Creighton’s Macdonald, which had celebrated Canada’s beginning, Grant lamented its end. For Grant, the dream of a North American alternative to American liberal, corporate society had been impossible. Diefenbaker was the nation’s last, half-blind defender, an inadequate tragic hero acting with courage and instinctive wisdom in a hopeless cause. Paradoxically, Lament for a Nation made Diefenbaker a historical figure of consequence and – perhaps surprisingly – gave inspiration to a new generation of intellectual nationalists who made their influence felt in all three national parties during the decade that followed. In Grant’s prose the legend had taken wing.

As he was mythologized, so he was demonized. In 1964, wrote John Saywell, Canada was a country divided over language and regionalism, in which traditions, loyalties, and views of the nation were in conflict. Parliament was wounded and, in the eyes of many, antiquated; and yet, puzzlingly, the men in it “were of an unusually high calibre. To resolve the paradox many observers were forced to conclude that the political and parliamentary process lay at the mercy of one man, whose natural desire to return to office and whose simplistic view of the nation’s problems threatened to do irreparable damage to his party, if not to his country.”74

As the year began, Diefenbaker toured the country denouncing Liberal approaches to national unity, pleading that Canada was one nation, not two. An element in that campaign was his effort to silence Conservative critics of his own leadership before the annual meeting of the party association at the beginning of February. In mid-January a Quebec constituency association circulated a letter to all constituency associations urging support for a leadership convention in 1964; and in Toronto, John Bassett and others promoted a vote of confidence in the leader to be conducted by secret ballot at the annual meeting. Diefenbaker’s approach to criticism was almost the same as it had always been. He expected loyalty. He did not engage in extended negotiation with his opponents, but appealed beyond them to the broader party he had created, talking in vague terms of “the Toronto clique,” or “the financial interests,” or “the Warwicks of the Conservative Party” who opposed him. He did not attempt to organize or direct his own campaign of support, beyond falling in with one crucial encounter arranged by David Walker and Ted Rogers. Just before Christmas in 1963 he accepted an invitation to dinner at the Rogers home, where John Bassett would also be present. He told Elmer that “I am not looking forward to it in sweet contemplation. However, if I see him and there is no change in his attitude I will feel that I have done everything possible.” That meeting led to another, private one in early January, which Diefenbaker thought had “turned out very well … Time will tell but I am hopeful that after the Annual Meeting the Telegram may decide to come back to the Progressive Conservative party. If it does that will be beneficial.”75

The meeting apparently resulted in a real and crucial compromise. When Diefenbaker addressed the annual meeting on February 4, 1964, and called for the expected vote of confidence in his leadership, he told delegates that he was ready to accept a secret ballot if that was what they wished. The same day the lead editorial in the Telegram, titled “Day of Decision,” called for an overwhelming vote of confidence in Diefenbaker – “whether it is a standing show of hands or a secret ballot.”76 Those two changes of position weakened the opposition to Diefenbaker. The motion for a secret ballot was defeated by three to one, and the motion of confidence, in an open vote, carried almost unanimously. About thirty opponents, including Douglas Harkness and J.M. Macdonnell, stood prominently together to register their dissent amid taunts from the leader’s supporters. More abstained from voting. Diefenbaker thought he had disposed of the challenge for good, but that was clearly wishful thinking. “We cannot believe,” commented the Globe and Mail, “that it is the end of the story, that a great party has really resigned itself to go into the next election behind a man who has proved he cannot lead.” Even the Telegram remained sceptical of a leader who still failed to appreciate that “the job of restoring the party’s fortunes demands conciliatory gestures on both sides.” But Michael Wardell’s Fredericton Gleaner judged that the endorsement of Diefenbaker was a “big decision, a noble, correct and triumphant one.”77

To avoid damaging defections from the Quebec wing of the party, Diefenbaker attended a meeting of the Quebec caucus the next day and endorsed Léon Balcer as his Quebec lieutenant and “provincial leader of the federal party in Quebec.” Balcer, he roundly declared, was a modern George-Etienne Cartier to his own Macdonald, and he would live in history. When the House of Commons opened two weeks later, Diefenbaker had rearranged the party’s seating to place Balcer beside him on the front bench. But he denied that Balcer held the position of deputy leader or chief lieutenant. Balcer expressed his puzzlement to reporters.78

As a further symbol of reconciliation, the annual meeting elected Dalton Camp as the new president of the party, succeeding Diefenbaker’s critic Egan Chambers. In his acceptance speech, Camp declared that the national association must be “in the service of the Parliamentary Party. Their policy must be our policy. And their leadership is ours, to be sustained and championed, supported and upheld.” That was, precisely, the view of John Diefenbaker, who knew that his strongest supporters were in the parliamentary caucus.79 But under Camp’s inspiration the party was also thinking ahead, planning for renewed communication between party and leader – which he promised would be “cordial … confidential … candid” – and for a policy conference modelled on the Liberal Party’s 1960 Kingston conference.