1967-1979

AFTER NOVEMBER 15, DIEFENBAKER WAS DELUGED WITH MESSAGES of sympathy, delivered by telegram, telephone, letter, or by “tear-stained visitors,” almost all of them assuming he would immediately resign as leader of the party. Liberal MPs, who only months before had shown their contempt and hatred for him in the House, let him know of their respect and avoided mention of his embarrassments in debate. Paul Martin told Jim Johnston: “We’ve had plenty of differences, but I just want you to know that I don’t think he should ever have had to take that.”1 Diefenbaker did not resign, but consulted endlessly with his advisers Jim Johnston, Gordon Churchill, Alvin Hamilton, Waldo Monteith, David Walker, and others. Loyalists and dissidents alike, in caucus and national executive, were concerned to hold the party’s remnants together. As centennial year began with no word from Diefenbaker about his plans, MPs reported growing dissatisfaction in the constituencies. Johnston expected mass desertions, and shared the opinion of Churchill and Monteith that Diefenbaker should bow out in favour of an interim leader. The right occasion seemed to be a free-time CBC broadcast on “The Nation’s Business” scheduled for January 18. On the day before, Diefenbaker called Johnston in to say that “the time had come for him to speak. He had been silent, and the party had been floundering.” Davie Fulton was the only candidate for the leadership who had made his intentions clear, and the Chief was not about to let Fulton succeed him. Johnston went home to draft a resignation statement hedged with qualifiers, and returned the next morning to find Diefenbaker and his staff preparing a different speech. “Don’t you see that once I say I am going, I have no more power left to hold this party together? I must stop Fulton.” Diefenbaker gleefully seized Johnston’s statement for his archives, but when Churchill and Monteith arrived he took it from his briefcase and read it to them. They laughed. As Diefenbaker finished, Johnston grabbed the page and tore it to pieces. “Here, that’s mine!” Diefenbaker shouted. “You can’t do that. You’ve destroyed the evidence.”2

Diefenbaker taped the broadcast in ebullient mood. He thanked the “thousands of Canadians” who had recently sent him warm messages, deplored the divisions in the party provoked by Dalton Camp, and called for an immediate leadership convention to be made up entirely of democratically elected constituency delegates. He would not allow the party to become “the plaything or the puppet of a powerful few.” He left his own future typically obscure. “I know that some will interpret what I am saying as being a swan song. Let me say at once – this is no swan song. Those who will interpret it that way do not know me. I have never in the past, and I shall not now, desert the course of a life-time, of at all times upholding principle and standing for those things which in my opinion are good for Canada, for the people of this nation – never forgetting the humblest of our people.”3 What did he mean? What his aides in the studio could see was that “half the staff in the control room was in laughter.” What he had done was to force Dalton Camp to react to the unexpected – if any surprise from the Chief could be called unexpected. Camp announced a meeting of the party’s executive committee for January 28 and suggested that the convention would take place in the autumn.

Diefenbaker had not reopened the fight against a leadership convention, but his allies hoped to command a majority in the executive meeting and so to confine his opponents at every turn. They failed to do so. Camp had persuaded Eddie Goodman to become chairman of the convention and the planning committee, which allowed Camp to step out of Diefenbaker’s focus and to canvass his own prospects as a potential candidate. When the meeting opened, Camp vacated the chair, the meeting transformed itself into the convention committee, and Goodman was confirmed as chairman. Roger Régimbal, a Quebec MP supported by the Diefenbaker lobby, was elected co-chairman. The meeting agreed that delegates should be elected from constituencies on the basis of the new, 1965 redistribution, which would require several months of reorganization and unsettle entrenched local executives. Diefenbaker’s demand that delegates-at-large should be excluded was rejected. But there was no agreement on a convention date. Johnston, in consultation by telephone with Diefenbaker, who was away on a fishing holiday in Florida, gained agreement that the date should be “not later than September,” to be confirmed after Goodman met with Diefenbaker on his return. Two weeks later the committee settled on an early September gathering in Toronto.4

Under Goodman’s sure touch, the convention planning committee worked in astonishing harmony for five months, satisfying the pro-Diefenbaker faction with its even-handedness. The spirit of cooperation was undoubtedly aided by the general assumption that Diefenbaker – although he had made no commitment – would not himself be a candidate. But with Diefenbaker there was always ambiguity. When the convention committee met in Victoria in June, it faced potential deadlock over the issue of the leader’s place on the program and the closing time for nominations. The Chief wished to address delegates on the opening night of the convention. Goodman was willing – as long as Diefenbaker himself was not a candidate for the leadership; so he planned that nominations should close that afternoon. Diefenbaker protested that he had a right to address the convention as leader without revealing whether or not he would be a candidate for his own succession. Under threat from the pro-Diefenbaker members of the committee that they would resign at once if his request were rejected – and that Diefenbaker, too, would instantly vacate the leadership – Goodman and the committee made a partial concession. Above all, they were concerned to restore the party’s public reputation for fairness and unity after the discords of the previous years. Diefenbaker would go onto the opening night program whether or not he was a candidate, but nominations would still close before he spoke. For two months Diefenbaker grumbled and threatened in private, until Goodman, after consultation, gave way just two weeks before the convention. Nominations would not close until the morning after Diefenbaker’s address. He would be allowed to keep both country and party in suspense until the last possible moment. It was not clear whether this was, for Diefenbaker, a small private war of personal dignity or part of some larger tactical campaign for advantage. Perhaps he did not know himself.5

Through the genial summer of centennial year and Expo 67, the Conservative Party prepared, in relaxed mood, for its convention of renewal. Davie Fulton and George Hees had been declared candidates, running hard, since February. Michael Starr, Wallace McCutcheon, and Alvin Hamilton soon joined the field. In June Donald Fleming came in: “running backwards,” as James Johnston put it, apparently prodded out of retirement by Diefenbaker’s encouragement. The three Tory premiers, John Robarts, Duff Roblin, and Robert Stanfield, seemed to be out of the race. Dalton Camp remained an enigma: He showed some preference for Stanfield or Roblin, but did not rule himself out, and kept a shadow organization at the ready. Diefenbaker talked privately with Stanfield about what might have become an endorsement, but that apparently came to nothing because the Chief expressed doubts about the Nova Scotia premier’s stance on the “two nations.” After a landslide provincial electoral victory in May, Stanfield became the focus of increased speculation throughout June. Roblin and Camp played coy until mid-July, when Stanfield entered the race and Camp chose to support his old Maritime compatriot. Two weeks later Roblin, after months of indecision, announced his candidacy as well. With their reputations unsullied by the prolonged civil wars of the federal party, the two premiers quickly came to the front in the race for delegate support. Diefenbaker himself made no preparations for a campaign, although two young enthusiasts, Keith Martin and Bill Hatton, created a skeletal Youth for Dief organization to show their affection for him at the convention. But if Diefenbaker wished to find a challenge in the contest, he could find it in the presence of his nemesis Dalton Camp as chief strategist and speechwriter for Robert Stanfield.6

Diefenbaker preferred silence on the leadership contest, as his friends provided him with daily accounts of the latest gossip. A series of events during the summer – all of them welcomed and encouraged by the Chief – contributed to the growing Diefenbaker legend. On July 21 he attended the dedication of Diefenbaker Lake, the vast reservoir created on the South Saskatchewan River above Saskatoon by completion of the Gardiner Dam – the two names now twinned forever on the landscape as they had been in political combat over thirty years. In Regina in August, the leader dedicated the old family homestead building, which had been moved by Ross Thatcher’s provincial Liberal government to a new site at Wascana Centre on the grounds of the provincial legislature. Saskatoon gave his name to a city park. And just before the leadership convention, RCA Victor released a long-play recording of Diefenbaker in reminiscence, reading his “I am a Canadian” pledge from his Bill of Rights speech, chuckling and telling anecdotes about his heroes John A. Macdonald, Wilfrid Laurier, Winston Churchill, and R.B. Bennett. The advance order, RCA reported, was the largest in Canadian history.7

Goodman, Régimbal, and Camp, hoping to supplement the leadership contest with some policy discussion that would restore the party’s credit among the thinking classes, planned a policy conference to precede the convention. It took place at Montmorency Falls, Quebec, at the beginning of August, under the chairmanship of the Ontario minister of education, William Davis. The conference, Goodman felt, was “almost a resounding success.” Just two weeks after Charles de Gaulle made his triumphal progress between Quebec City and Montreal along the chemin du roy and startled Canadians with his cry from the balcony of Montreal City Hall, “Vive le Québec … Vive le Québec libre!” the Conservative meeting threw the party into the maelstrom.

The conference [Goodman explained] accepted the concept of deux nations not in the sense of two political states, but as a recognition of the country’s two founding peoples: an English community and French community with distinct cultural and linguistic backgrounds. It was an effort to show Quebec that the Progressive Conservative Party was sympathetic to its legitimate aspirations to maintain the existence of Canada’s French culture. Unfortunately, these ideas are difficult to express, but easy to distort. The accusation was made by some of the delegates at Montmorency, led by Dick Bell in a spirited debate with Marcel Faribault, that we were advocating two sovereign states, or separate political status for Quebec. This was the beginning of an issue that was to be shrewdly manipulated by Pierre Trudeau and the Liberals to defeat the Tories in 1968.8

Before Pierre Trudeau seized upon it, “two nations” was an alarm signal for John Diefenbaker. He denounced the party’s use of the phrase at a press conference on September 1. “When you talk about special status and Two Nations, that proposition will place all Canadians who are of other racial origins than English and French in a secondary position. All through my life, one of the things I’ve tried to do is to bring about in this nation citizenship not dependent on race or colour, blood counts or origin.”9 Two days before the formal opening of the convention, Goodman’s policy committee endorsed the Montmorency resolution for recommendation to the convention.

BECAUSE HE COULD NEVER BRING HIMSELF TO OFFER HIS RESIGNATION FROM THE leadership of the Progressive Conservative Party, Diefenbaker brought turmoil to his party and disenchantment to his country. For years he filled the air with vague and reckless talk of conspiracies, dark networks of enemies who were working to dismantle Canada or destroy its independence – first in league with Washington, then in league with Quebec, always in league with the Liberal Party. He made the paranoid style dominant in Canadian politics as it had not been since the days of William Aberhart and Mitchell Hepburn; and by the time of the 1966 annual meeting of the party, he found the very conception-point of conspiracy in the mind of Dalton Camp.

For Diefenbaker, Camp remained thereafter the fount of evil – and the source of the Chief’s own justification. The campaign to destroy John Diefenbaker – which reached its dramatic climax in Camp’s orchestration of the 1966 defeat – was, after all, the campaign to destroy Diefenbaker’s Canada. Personal and national destiny had become one. In the twilight of his life, Diefenbaker had unexpectedly claimed a destiny he had glimpsed in his youth and then lost for decades. After 1957, when the nation responded to his beguiling call, he had found it again. “One Canada” from sea to sea, Macdonald’s and Cartier’s political nation, was to be fulfilled a century later at the hands of their authentic heir. It must not be destroyed, by Pearson, by Kennedy, by Camp, by anyone. Of course Diefenbaker could not abandon his destiny; of course he could not abandon his leadership of the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada. What was at stake was not a personal career but a nation. So far had hubris taken him.

As the party conflicts and the election campaigns revealed, Diefenbaker had many followers in his mission. Some, like Arthur Maloney, were by 1967 followers out of decent loyalty. Some, in the caucus, were followers who knew their political lives depended on the Chief’s presence. Some were admirers – worshippers even – who had been inspired by Diefenbaker in 1958 and had kept the faith. Some – westerners, maritimers, those marginalized by region, race, national origin – were followers because he was one of them. Some were new loyalists won by the persistence and courage of this man under siege. Some were followers because – despite or apart from policy – they found something unbearably smug and arrogant in the Liberal Party, or because they resented its complacency. Some were followers because they possessed the darker prejudices Diefenbaker’s words and silences called forth. Some shared his bitterness. By 1967 it was difficult for Canadians – Conservatives or not – to remain indifferent to the man. The followers who remained with him had made an emphatic choice, as had those who departed to another party or another faction. At the leadership convention John Diefenbaker would draw attention, perhaps for the last time, to the strengths he had added to the party and the divisions he had created within it.

OLIVE AND JOHN ARRIVED AT THE ROYAL YORK HOTEL ON THE DAY BEFORE THE convention, to be greeted by a crowd of several hundred reporters and spectators, including “eight middle-aged to elderly women with Diefenbaker placards in a kick-line. One of the women held a rose between her teeth.” Close by, James Johnston was confronted by another band of “little old ladies supporting Mr. Diefenbaker,” who mistook him for Dalton Camp and threatened him with physical violence. Diefenbaker – once settled into the vice-regal suite – began to receive a stream of candidates, each of them seeking credit in reconciliation with the old Chief. Eventually all but McCutcheon and Fulton made calls on the leader. He lectured them on the evils of a “two nations” policy – and said nothing definite about his own intentions. On Thursday morning, September 7, the Toronto Star reported that he had told Duff Roblin he would walk out of the convention if it endorsed the idea of “two nations.” The organizers made their final preparations for the televised opening and Diefenbaker’s address at Maple Leaf Gardens – and crossed their fingers about what he might say. No one knew whether he would announce his own candidacy.10

Maple Leaf Gardens was decked out in blue banners and portraits of all the Conservative leaders since Confederation when Eddie Goodman opened proceedings with his greeting, “Good evening, sports fans,” on Thursday evening.11 Goodman and John Robarts welcomed the audience; and then, to the chairman’s surprise, there was a flurry at the other end of the arena. “The doors at the back of the Gardens suddenly swung open, and behind a swirl of pipers John and Olive Diefenbaker marched in … It was too late for officialdom to stop the display. Goodman was one of the few who seemed to appreciate the irony of it all, and a grin sneaked across his face. He had tried hard to keep Diefenbaker from speaking on the convention’s opening night. But he had lost, and now the old Chief had arrived with his army of pipers, and on national television too.”12 This was the work of the Youth for Dief delegates, whom Diefenbaker had embraced in delicious good humour. Once the hall had settled, Goodman introduced two keynote speakers, Alberta’s promising new Tory leader, Peter Lougheed, and the French-speaking co-chairman, Roger Régimbal. But they were only a sideshow. The crowds awaited the Chief. Anticipating the occasion, the Globe and Mail asked the drama teacher and producer Eli Rill to describe it through professional eyes. His report was headed: “Is Dief Another Barrymore?” “He came on stage with what they revere in the acting profession, the thing they called simply presence – the air of holding an audience’s attention just by being there. And, as any performer does, he made it clear that he could rise above his material, his script – even when he had written the script himself. What he was saying was of less value than how he said it.”

The supporting cast “faded into the background after the star appeared … But what chance did they have – they were up against the shades of Garrick and Booth and Barrymore.” The doubters soon “fell victim to the magnetism, the projection, the charisma (as the U.S. political mind-benders are calling it now) of Diefenbaker playing front and centre.” Diefenbaker accepted a presentation painting, and stepped to the podium.

He started low-key, a shade solemn, not to make too sudden a shift from a gift-laden lady’s recital of the history of an obscure painter in water colors. His words, he said, would be inadequate. But he was Mark Antony over Caesar’s body, re-shaping a mixed collection of emotions and attitudes into a unified, loud-voiced People’s Party, “for all Canadians” – and conceivably all for Diefenbaker. With jabbing, emphasizing, accusing finger and head-thrusts that gave no hint of galloping old age, he built towards a passion suitable for defending the Monarchy.

He quoted Scripture, touched lightly on his party’s support of manly sports, invoked the unpolitical name of Bobby Hull. Then he continued his overt wooing of French Canada – low and vibrant at first, then building to a reverberant punch line – “I shall never agree to second-class citizenship for 6,000,000 people!”13

He plunged on, the spellbinder stilling the applause-mad audience time and again, holding them in check, playing them like a lyre, his tune a nostalgic paean of East York, Don Mills, all of Canada. When a rhetorical question drew an unexpected answer from the gods, he jumped on it like a tiger, used it to tease still another accent for his thesis. Now he crouched in defiance of the charge that he was growing old. Now, with fist clenched like any melodramatic ham, he turned the jaded gesture into significance.

His jowls quivered, as he repudiated the disaster-bound course of the Liberal government.

Now he switched to schoolmaster tones and quoted poetry supporting the One Nation policy. Speaking of devotion and dedication to fighting for those things “I have fought for all my life,” he intoned the great line, “I am still here!”

We listened, and listened, but he did not finish the drama – a drama that has been longer than the Oresteia and Hardy’s The Dynasts combined. He left us longing for the final curtain – a cliff-hanger if ever there was one. The rest was silence, though Hamlet was not dead. Or was he? Was Lear dead – or was he still raging on the heath, conducting the winds and hurricanes as though they were the Ottawa Symphony?

And Mr. Diefenbaker spoke, from time to time, in French. Nobody would mistake him for Mounet Sully reciting Racine or Corneille. His accent, quite simply, is agonizing, sometimes reducing the words to gibberish. But by God, we listen, doubly riveted – by the rolling waves of sound, and by the suspense of wondering whether it will mean anything.14

The speech was a dramatic triumph for the old stager, but it left the national audience puzzled. It had expected a farewell. Next morning a banner headline in the Victoria Daily Colonist read: “He wouldn’t say yes/ He wouldn’t say no.”15 As the nomination lists for the leadership contest were about to close at 10 am, John Diefenbaker issued a brief statement:

Last evening I stated I could not consider being a candidate for the leadership of the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada if this Party Convention accepts the TWO NATION concept as approved of by the Sub-Committee and by the Policy Committee.

I remain unchanged and unswerving in my opposition to that concept.

The TWO NATION Policy is not to come before the Convention until Saturday morning and as nominations close at ten o’clock this morning my name is being placed in nomination.16

He had no chance of re-election. But he would keep his party in turmoil to the end – and he would go down fighting.

The same morning the Globe and Mail called the “two nations” resolution “a landmark of clarity.” The words that offended Diefenbaker read: “That Canada is and should be a federal state; that Canada is composed of the original inhabitants of this land and the two founding peoples (deux nations) with historic rights, who have been and continue to be joined by people from many lands; that the Constitution should be such as to permit and encourage the full and harmonious growth and development in equality of all Canadians.” The Globe commented: “The Canadian who can find in it the seeds of our national disruption, the Canadian who can come away from it convinced that it was concocted with diabolical cunning, is quite a fellow. In fact, he is the fellow that John Diefenbaker is seeking to join him in his cockeyed campaign to have the words deux nations expunged from the record before the convention ends. And, of course, the old chief is finding support. His stock has never been higher – out in Social Credit country. Telegrams have been pouring in – from the Nineteenth Century.”17

Eddie Goodman knew that Diefenbaker’s nomination spelled trouble: not because he might win, but because he was provoking division at the very moment when the party hoped to regain popularity with a fresh image of unity and reconciliation. Soon after the Chief’s nomination, Gordon Churchill called to ask for a meeting with Goodman and Davis. “Benny,” Churchill said to Goodman, “I want you to know that when Bill Davis puts his report to the plenary session Dief and his supporters are going to vigorously oppose the deux nations resolution.” Churchill, accompanied by the Chief’s friend Joel Aldred, met with Goodman and Davis that afternoon to argue that the resolution would open the way to special status for Quebec. Goodman and Davis could not persuade them that this was a misconception. In frustration, Goodman told them that he had “no intention of letting you fellows destroy this convention and the party.” He would ask Davis simply to table the policy report without comment or debate, and move on. There would be no vote to adopt or reject it. Churchill, whom Goodman accepted as “a man of good, if often mistaken, intentions,” agreed.

When Davis presented the report to the convention on Saturday for tabling, only one delegate – Diefenbaker’s spirited advocate Charlotte Whitton – demanded the right to speak. Goodman ordered her microphone turned off, and for a few moments she mouthed silent imprecations until the audience began to boo. “I made a point of order,” Goodman remembered, “stopped the discussion, Whitton screamed ‘Fascist’ and the crisis was averted.”18

After a dull round of nominating speeches and addresses from all the candidates – including Diefenbaker – on Friday evening, delegates trooped to the floor for the balloting on Saturday afternoon. Goodman’s importation of American voting machines, intended to speed up the balloting, caused interminable confusion instead. Lines of delegates snaked slowly forward for the first ballot as the temperature in the Gardens rose to steamy heights. Diefenbaker boasted to reporters from a box seat about the disputed policy resolution: “They didn’t dare bring that before the convention … They had it all arranged. It was going to be done well. It was going to be put through, and everyone was going to look happy … Principles must never be subverted in the hope of political gain.”19 He sat for a while with the ex-leader John Bracken. The Toronto Stars Dominique Clift told Jim Johnston: “I’ve got a theory why he’s doing it. You anglais are funny. You are all masochists. Dief knows what they did to John Bracken, and now they are doing it to him. He wants Bracken there beside him so everybody can see what’s gone on before.” He was joined in his box during the day by his brother, Elmer; his step-daughter, Carolyn Weir, and her son John; and by Helen Brunt, Joel Aldred, and the Paul Lafontaines. Others moved in and out during the voting.20

Finally, the first ballot results were announced. With more than 2200 votes cast, Robert Stanfield was in the lead with 519. Duff Roblin and Davie Fulton were second and third, with 349 and 343 votes. George Hees was next, with 295. Diefenbaker followed in fifth place, with 271 votes. He looked pained and “sank a little deeper into his chair, his tremor more intense.” He took a short walk with Olive, returned to his seat, and huddled in conversation with Gordon Churchill. He did not withdraw. On the second ballot, as Stanfield and Roblin both gained votes, Diefenbaker remained in fifth place with a reduced count of 172. This time, “he went for another walk, then holed up with his advisers, and without Mrs. Diefenbaker, in a small room guarded by police. The rumor spread quickly through the halls that he was writing his resignation, and would announce it when he emerged.” Instead he returned to his seat and voted for a third time. That ballot left Stanfield and Roblin in their steady climb, with Stanfield in the lead. Diefenbaker – still in fifth place – fell to 114. Olive had earlier donned dark glasses, and now “the first few trickles of tears” ran down below them. The Diefenbakers, Walker, Churchill, and Johnston rose to leave with a police escort, a few voices calling after them, “Don’t go, John.” Half a block from Maple Leaf Gardens, Johnston left the limousine to return to the arena with Diefenbaker’s scrawled note of withdrawal from the race.21

It had been a hard day. At the Royal York an aide told reporters that Diefenbaker would not appear again that evening. But less than two hours later, as voting began on the fifth and final ballot – between Stanfield and Roblin – the Diefenbakers took their seats again at the Gardens. When Stanfield’s victory was declared, the Diefenbakers applauded and walked together to the podium. Eddie Goodman introduced the Chief as “the greatest Canadian of the century.” Diefenbaker offered his congratulations to Stanfield, pleaded for loyalty to the new leader, and echoed R.B. Bennett’s retirement statement from 1938: “Don’t, as the fires of controversy rage around your leader, add gasoline to the flames.” In parting he left two more barbed reminders to those who followed.

My course has come to an end. I have fought your battles, and you have given that loyalty that led us to victory more often than the party has ever had since the days of Sir John A. Macdonald.

In my retiring, I have nothing to withdraw in my desire to see Canada, my country and your country, one nation.

But it was, even so, a gracious departure. “A little of the bitterness showed through,” wrote George Bain, “and the short farewell just missed nobility. But it took great courage just to stand there and deliver it at all, for it had been an awful day for him.” As he left the arena and returned to his hotel suite – the burdens relinquished – he had time for conversations with clusters of admirers who would not easily let him pass.22

JOHN DIEFENBAKER WAS NO LONGER LEADER OF HIS PARTY, AND DESPITE HIS PUBLIC concession, he was bitter. His resentment was focused on his successor, Robert Stanfield – who had commented lightly as he began his acceptance speech, “Personally, I’m determined to get along with that fellow Camp.”23 When Diefenbaker and Stanfield met privately at the Royal York Hotel two days later, Diefenbaker began by telling him he was “deeply concerned” by those words. Stanfield responded that he had been under strain, and that after Diefenbaker’s withdrawal he had heard that the Chief had advised his supporters to vote for Roblin. Diefenbaker did not deny the story. Next Diefenbaker expressed concern that when the reporter Gordon Sinclair had asked Stanfield: “Are you going to kick him out of Stornoway at once?” Stanfield had answered: “Well, Stornoway is the home of the Leader of the Opposition.” Stanfield apologized for having made a thoughtless reply, and insisted he would not rush the Diefenbakers out of the house. Diefenbaker challenged Stanfield about new arrangements for his office and staff, and received what he thought was a “noncommittal” reply. In a long memo after the meeting, Diefenbaker described it – perhaps generously – as “cool and reserved,” although he noted that Stanfield “did indicate that he was firmly attached to me.”24 An hour later, in a telephone conversation with Gordon Churchill, Diefenbaker said: “He came to see me a little while ago. It is obvious that he does not want me in the House and it is also obvious that I get out of my office at once although he did not say so. It was also obvious that I should get out of the house.”25

Diefenbaker’s bile rose as he talked further with his supporters during the day. To one friend he reflected that the remark about Camp was “a deliberate slap. I don’t know whether I should have gone back there at the end or not.” He commented to Churchill about George Bain’s commentary: “You will have to get the ‘Globe & Mail.’ It said my speech at the end was quite remarkable. It just stopped short of nobility. Now what kind of bastardy is that.” Next day Diefenbaker wrote: “The press have slain me and now they have mutilated me.”26

But there were unusual efforts to show him kindness. On his seventy-second birthday on September 18, as he was moving out of the leader’s parliamentary offices, the staff gave him a birthday party at the home of his assistant Tom Van Dusen. Diefenbaker told stories to the four youngest Van Dusen children, sang several verses of “an interminable western ballad,” and stayed until late in the evening. Two nights later, the parliamentary press gallery entertained him at an unusual retirement dinner, where he told them that he would never speak in the House again. The vow lasted until late in November.27

Diefenbaker and Olive made a brief visit to Saskatchewan, where his Prince Albert supporters put on a “Carry on, John” rally that attracted fifteen hundred locals. The mayor presented Diefenbaker with a mounted northern lake trout weighing fifty pounds and labelled “You’ve tackled many big ones, Keep Going.” Despite the crowds and the affection, the Chief was unresponsive, still bitter and irritable. He left Prince Albert to attend similar events in Regina and Moose Jaw.28 Diefenbaker returned to Ottawa and his new corner office in the Centre Block, looking out to the northwest across the Ottawa River to the Gatineau Hills beyond Hull. There he hung his giant bluefish and his print of the naval battle from the war of 1812, trophies of his encounters with John Kennedy. Later – when it became clear that Robert Stanfield had decided to keep Dalton Camp at a distance as a signal of reconciliation with the Diefenbaker loyalists – the Chief placed prominently in his outer office a Telegram cartoon of Camp slinking silently away from Ottawa. The national archivist agreed to take Diefenbaker’s papers and records in temporary storage, while two padlocked filing cabinets of his confidential papers remained close by him in his office. He talked of writing his memoirs. During the autumn the Diefenbakers bought their own home in Rockcliffe Park and transformed the basement recreation room into a miniature historical museum decorated with Macdonaldiana, gifts from his foreign visits, Indian headdresses, and the brilliant gowns marking his many honorary doctorates.

The stream of public events flowed on without him. The old man appeared regularly in the House for the daily Question Period and then withdrew, taking no part in his own party’s deliberations in caucus. He had his friends and loyalists still, but hardly felt himself a member of the party that had repudiated him. In November the Ontario premier John Robarts hosted his Confederation of Tomorrow conference of the provinces, and unknowingly began a twenty-five-year cycle of constitutional negotiations. Stanfield won a by-election to parliament in the same month – but Diefenbaker refused to escort the leader as he took his seat in the chamber, and instead stayed away from the House that afternoon. On December 15 Mike Pearson announced his own decision to retire from politics.

When the new leader of the Liberal Party, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, dissolved the House in April 1968 for a June general election, Diefenbaker belatedly accepted nomination in Prince Albert, where his re-election was a certainty. He remained barely on speaking terms with Stanfield. Diefenbaker and Trudeau – both dissidents by nature, both scrappers, both favourites of the media – established an immediate relationship of wary mutual respect. Trudeau endorsed Diefenbaker’s commitment to one nation, and the Chief found perverse comfort in a Prince Albert campaign that was as personal and devoid of association with his national party as in the old days. He wished for Stanfield’s failure. But throughout the west the Conservative Party needed the Chief’s candidacy – however cool he might be to the new leadership and its policies.

For six weeks during the campaign the Diefenbakers occupied a suite in the Flamingo Motel in Prince Albert – where John, during Olive’s absences, exchanged mildly racy jokes with his cronies about Gerda Munsinger and her two ministerial friends, and Olive soothed his frequent fits of distemper. His loyal Prince Albert associates Dick Spencer, Max Carment, Ed Topping, Glen Green, and Art Pearson organized the campaign in a newly enlarged constituency, and found busywork for the sixteen-year-old Youth for Dief refugee Sean O’Sullivan, whom Diefenbaker had unaccountably imported from Hamilton for the duration of the campaign. In Spencer’s eyes, O’Sullivan provided the Chief with adoration, and spoke the words of pain about his rejection that Diefenbaker himself could not express. For the local campaign workers, O’Sullivan’s most useful function was to persuade a contemptuous Chief of the value of promotional “bumperschtickers.” As usual, Elmer was present for the duration, “getting on Dief’s nerves,” O’Sullivan remembered, “and driving Olive crazy … Dief gave Elmer money and Elmer’s task during the campaign was to buy King Edward cigars and pass them out on the Indian reserves on behalf of his brother.”29

Diefenbaker campaigned slowly in his riding, chatting at lunch counters, attending baseball games, casually visiting voters’ homes to drink too much tea and coffee. In his speeches he relentlessly attacked “two nations,” even though no party was committed to the doctrine he imagined, but he gradually added lines that challenged Trudeau’s unspecified policies. As the campaign neared its conclusion, Stanfield sought Diefenbaker’s support at a rally in Saskatoon, an appearance that might somehow distinguish Diefenbaker’s commitment to one Canada from that of Trudeau and the Liberals. Diefenbaker refused, and instead devised an awkward meeting at Saskatoon airport and a joint tour of the Western Development Museum – where they argued over “two nations.” That evening Stanfield told his audience impatiently that he had never been an advocate of “two nations” or “special status” for Quebec. “My impression of the encounter,” Diefenbaker’s constituency president, Dick Spencer, wrote about the meeting with Stanfield, “was that it was a mean-spirited affair on Dief’s part, embarrassing and dangerous to his legend. I knew in my heart that Dief and Mrs. D. couldn’t help themselves, such was the anger and the hurt the very mention of Stanfield’s name could summon. But how much more sensible and honourable a course it would have been to excuse themselves from the Saskatoon rendezvous and stay home with us. It was time for the campaign of 1968 to draw to a close.” Only in two last-minute visits to rallies in Manitoba did Diefenbaker overcome his resentments and offer overt support for the leadership of his successor.30

Across the nation, the wave of adolescent Trudeaumania swept away opposition. On election night, the Chief revelled in Stanfield’s humiliation.

In the Maritime provinces the party made gains, but in Quebec and Ontario it met disaster, and in the west it lost twenty seats. Diefenbaker gloated as his enemies Dalton Camp, Wallace McCutcheon, Marcel Faribault, Jean Wadds, Richard Bell, and Duff Roblin went down in their constituencies. The party won a total of seventy-two seats, twenty-five fewer than the Chief had delivered in 1965. But Diefenbaker won his own seat by 8600 votes over his NDP challenger. “The Conservative Party,” he said on national television, “has suffered a calamitous disaster.” The old man’s eyes that evening “were more than twinkling, they were dancing. It was triumph. And Olive felt imperial. What a night for the two of them!”31 The Diefenbakers returned to Ottawa reinvigorated by the party’s failure.

JUSTIFIED AND WITHOUT OBLIGATION TO HIS PARTY, DIEFENBAKER RANGED FREE IN the new House of Commons, sometimes accepting the party line, sometimes ignoring it with impunity. Behind him he had a loyal claque of old Diefenbaker loyalists. Stanfield’s caucus had even less representation from the cities of the nation, from the educated and the affluent, than Diefenbaker’s after 1965. Stanfield’s advocate Heath Macquarrie thought that the new leader had “a dozen to twenty supporters in caucus, plus the Nova Scotians – less than thirty altogether.”32 He would be forced once more to seek reconciliation with his opponents in the party; and he did so, gradually and patiently. He consulted Diefenbaker from time to time and – despite frequent provocations – always treated him with courtesy and respect. Diefenbaker was reluctant to admit it.

Towards the Chief’s supporters in caucus Stanfield offered a similar display of confidence. Often they did not return it, regarding his tolerance as a sign of fatal weakness. The differences were revealed most dramatically in debate on Trudeau’s official languages bill in early 1969. The legislation established French and English as equal languages in federal departments and agencies; proposed the creation of “bilingual districts” where federal services would be available in both languages; and created a new office of language commissioner responsible to parliament. The measure was as profound an assertion of Canadian values as Diefenbaker’s Bill of Rights had been. But given the confusing debate on “two nations” that had preceded it, and the battle that was under way in Quebec over independence, the measure was controversial and easily distorted in English-speaking Canada. In the west, polls showed opposition as high as 70 percent. Robert Stanfield declared his support in principle, but many of Diefenbaker’s loyalists in caucus, under the strident leadership of the Albertan Jack Horner, announced their more passionate opposition. In May 1969 Diefenbaker joined the opponents in a mean House of Commons speech describing the proposed language commissioner as a “commissar,” a “dictator.” He dared Tory MPs to reject the advice of their leader and oppose the bill. On second reading, seventeen Conservatives, including Diefenbaker, voted against the bill and fourteen abstained. Stanfield carried only forty of his members with him. The next day, in caucus, the leader angrily denounced the rebels for forcing a recorded vote. “Their stupidity,” he said, “was exceeded only by their malice. There are some things in a political party one simply does not do to one’s colleagues.” He supported the bill because he sought the survival of a nationwide party, and he would countenance no further disobedience. The revolt collapsed under this show of firmness: the party united on all its proposals for amendments, and on third reading the bill passed on a voice vote. Diefenbaker’s claque might be a nuisance and an embarrassment, but the challenge to Stanfield’s leadership was hollow.33

There was one more brazen act in the summer of 1970, when Horner called a meeting of prairie Tory MPs for Saskatoon in August. Ostensibly the meeting would discuss agricultural policy; the real theme was Stanfield’s leadership. Diefenbaker and more than a dozen of his colleagues attended, dodging reporters and acting suitably conspiratorial. “Stanfield,” reported Anthony Westell in the Toronto Star, “had to spend the next week, when he should be undermining the government, hushing and shushing his own people, cooling off the row.” A few days later, in a visit to Alberta, he declared Horner and his group “very stupid” for holding the meeting behind his back.34 Diefenbaker was no longer a prime instigator of mischief, but he was loath to discourage anything that made life difficult for his Tory foes. In September he called reporters to his office to tell them he would not attend his party’s caucus when it discussed the Saskatoon meeting and the issue of unity because the meeting had not been secret. “A closed meeting,” he insisted, “is not a secret meeting.” He added gratuitously that Dalton Camp was again trying to dominate the party. “Psychologists,” he told them, “have long since determined that nothing is more disturbing for the human mind than for a person to have his victim still around after an assassination.”35

Like other ex–prime ministers, Diefenbaker enjoyed foreign journeys as a reminder of the privileges of power. He travelled in these years to Taiwan as the guest of the Chinese nationalist government, where he was entertained by Chiang Kai-shek; and in 1969 he drew headlines during a visit to the Soviet Union in the company of Joel Aldred. In Moscow he met with a Soviet deputy premier and, according to his own account, discussed the damming of the Bering Strait “to divert the warm Gulf Stream into the Arctic waters and make the Arctic coast habitable”; the construction of domed cities in the Canadian north “similar to some in the USSR with populations of 500,000 to 1,000,000”; and a scheme to heat the waters of Hudson Bay with nuclear energy to make Churchill, Manitoba, a year-round port. He discussed wheat purchases from Canada with the head of the Soviet grain agency; and in Kiev he declared Ukraine an independent state free of the Soviet Union and called for the establishment of a Canadian consulate-general in the Ukrainian capital. The Soviets seemed to treat these diverting fancies calmly.36

In 1970 Diefenbaker marked two notable anniversaries. On March 26 he celebrated the thirtieth anniversary of his entry into the House of Commons along with the Liberal solicitor general George McIlraith. Prime Minister Trudeau presented Diefenbaker with a blue carnation and McIlraith with a red one. Diefenbaker responded: “I have been to the mountaintops and I have been down in the valley. I do not want to mention personal matters, but on an occasion like this, I am filled with emotion. I do want to say that one’s happiness is greatly increased by having a wife to support, to stand and to counsel.” He added, “I am not passing that on to the Prime Minister by way of a suggestion, but I say to him that if he would follow my advice in that connection he would be amazed at the transition which would take place.” He warned the House that a Jewish congregation had presented him with a plaque of the Tree of Life and predicted he would live as long as Moses. That, he pointed out, was one hundred and twenty years.37 In September he celebrated his seventy-fifth birthday, in the afternoon at home with friends, in the evening at a reception in the Railway Committee Room of the House of Commons, where he was presented with a briefcase by his parliamentary colleagues. He took the briefcase home and slid it under a bed, where it rested for months until he opened it one day to discover that it contained hundreds of mint dollar bills.

Diefenbaker continued to rise early during this parliamentary term, to take a brisk morning walk, and to arrive at his office before 8 am. His days were still filled with movement and unexpected shifts of schedule, as he took telephone calls, greeted visiting friends, reporters, and gangs of invading school children, sat in the House for Question Period (where he could conjure up a noisy round of desk-thumping and insults at the flick of a phrase), and casually misplaced letters by throwing them into desk drawers out of reach of his secretaries. He brought two of the Youth for Dief disciples of 1967 into his office as staff assistants, first Keith Martin and later Sean O’Sullivan, to learn disorder at the hand of a master.

Full of good intentions, he began a desultory effort to put thoughts on paper for his memoirs. Harold Macmillan encouraged him and explained how he had organized his own massive and graceful volumes; John Gray of the

Macmillan Company of Canada gently prodded in the background; and for several months two academics taped his recollections while they tried to make sense of the vast and disorderly bulk of the Diefenbaker Papers stored in the Public Archives.38 But he was easily drawn back to his daily diversions and travels, and told visitors how the crowds that greeted him everywhere indicated he could make a successful return to power if he had the chance. After two years the first enterprise to produce his memoirs faded, and a succession of new literary advisers came briefly to his aid: Burt Richardson, Michael Wardell, Tom Van Dusen, Greg Guthrie, and finally John Munro and John Archer, who began to publish the memoirs with the first volume, One Canada: The Crusading Years, in 1975, when Diefenbaker reached the age of eighty. The second and third volumes followed in 1976 and 1977. In the meantime, Diefenbaker’s supporters Tom Van Dusen, Robert Coates, and James Johnston published their own anecdotal accounts of his now-legendary career, honouring the heroic battles of his later years and denouncing the infamies of Dalton Camp.39 Diefenbaker’s brother, Elmer, faithful, dependent, and infuriating to the last, died in 1971.

Diefenbaker could never escape for long the demons of resentment that haunted him in his last years. His mind worked steadily on schemes petty and grand, ludicrous and sublime, to achieve final revenge on his foes and redemption for himself. The audiences that greeted him with affection and curiosity in his unending journeys across the nation, the many awards he received for humanitarian service, the admiring attention he gained from young people who visited his office to hear his hoary anecdotes as fresh revelations of his spirit and humour, the plaques and geographical names and statues that began to give physical dimension to his memory, all pleased and comforted him. The legend - which he absorbed and transformed into his own memory of events - became one private means of dealing with his political failures and disappointments. The factual record - as others might recall or rediscover it - lost its substance. The legend became, for him, the Truth. It had a dark as well as a light side - and the dark side was as important as the light in his private scheme of self-justification. The dark side was the record of conspiracy and betrayal by his enemies and opponents, never justifiable and never fair. If there were failures to admit, then they were not personal failures but failures imposed by malign forces always beyond his control. He was both the hero and the victim of his destiny, and somehow beyond personal responsibility.

In the autumn of 1972 his envied political opponent Mike Pearson, who had retired to write and teach a seminar at Carleton University, published the first, widely acclaimed volume of his memoirs, Mike. Soon afterwards Pearson fell ill with cancer, and just after Christmas he died. His coffin stood for twenty-four hours in the hall of honour of the Parliament Buildings, where 12,000 people came in the December cold to revere his memory. The next day his funeral took place at Christ Church Cathedral, where the Very Rev. A.B. Moore saw him off gently with the words of a Chinese poet, “mak(ing) his way into the distance…playing his flute as he goes.”40 John Diefenbaker was there to reflect on time’s inexorable passage. Afterwards, he walked back to his office with a reporter and was asked whether, in death, he had kind words for Lester Bowles Pearson. Diefenbaker looked down for a long time in silence and at last shook his jowls and looked up: “He shouldn’t have won the Nobel Prize.”41

Mike Pearson had departed quietly, playing the flute as he went; but John Diefenbaker had something grander in mind to mark his own farewell. In the 1960s he had discussions with the University of Saskatchewan about placing his personal papers in a special collection there, but the university was reluctant to take on a collection so large and so expensive to maintain. When Diefenbaker was elected chancellor of the university in 1969, however, he announced at the installation ceremony that he was donating his papers to the university. The gift could not be refused, and in the succeeding years plans were developed, with support from both the provincial and federal governments, to establish the Diefenbaker Centre as his prime ministerial archive and museum. It was located on the high bluff above the South Saskatchewan River, and opened under its first director, John Munro, soon after Diefenbaker’s death. In its plan the centre owed inspiration to the Truman Library in Independence, Missouri. The Truman Library has its Oval Office, meticulously copied from the White House and furnished with Harry Truman’s office effects; the Diefenbaker Centre has not only the prime minister’s East Block office but the cabinet room as well, furnished as they were from 1957 to 1963 with Canadian relics. The centre was intended to live not only as a Diefenbaker archive, but as a focus for the study of prairie history.42

After 1968, Diefenbaker fought three more federal elections in his Prince Albert riding. By 1972 he had grown genuinely contemptuous of the rich and dilettantish playboy Pierre Trudeau - an attitude that sat more comfortably with Diefenbaker than his ambiguity of 1968. Now he could endorse his successor without reserve as a leader who would respect parliament and Canadian tradition. He fought the 1972 summer campaign with his old verve and aggression, attending political events in his own constituency and beyond on thirty-nine days. For his constituency president, Dick Spencer, there was one briefly alarming evening when Diefenbaker erupted fire over the presence in the constituency of Peter Newman: “You know he wants to destroy me! He’s a dangerous man … He’s tried before, you know. What did you tell him?” Eventually reassured, the Chief sank into his chair with resigned sighs of “Ah, well … Ah, well.” On the hustings he still enchanted the crowds - this time, dropping down into small prairie towns by helicopter. Diefenbaker coasted again to a comfortable victory, and watched the national returns with incredulity as Trudeau lost his majority and ended just a hair’s breadth ahead of Stanfield, 109 seats to 107. The NDP held the balance with thirty-one seats. “Dief was more at home in his own Tory Party that night,” reflected Spencer, “than he had been for some time.” And yet: “I do not know what was the greater, Dief’s satisfaction with the humbling of Pierre Elliott Trudeau or his relief that Stanfield had been denied power. I know the latter condition pleased Olive immensely … Now Dief saw another charismatic Canadian political leader wretchedly pulled from giddy heights down to the moor below. It was strangely satisfying.” Diefenbaker could look forward to yet another campaign.43

In 1974, at age seventy-eight, Diefenbaker was nominated, for the first time since 1957, without Olive at his side. She was in an Ottawa hospital, but sent a telegram promising to be in the constituency before long. The national campaign went badly for Stanfield from the beginning, as Trudeau campaigned vigorously against the Conservative call for price and wage controls. As so frequently before, Diefenbaker rejected his party’s program and went his own way. By election day the result was predictable: a new Liberal majority, 141 seats to 95. Diefenbaker’s majority increased to over eleven thousand. For Robert Stanfield, this looked like the end of the road.44 Two years later he was succeeded at a leadership convention by the unlikely choice of Joe Clark, one of those young students first drawn to a career in the Conservative Party by the inspiration of John Diefenbaker’s 1957 election campaign. Another one, Brian Mulroney, would drive Clark out and succeed him in 1983.

Diefenbaker took the draft manuscript of the second volume of his memoirs to Barbados for a month-long Christmas holiday in 1975, but that interlude was cut short when Olive, now seventy-three years old, suffered a mild stroke and partial paralysis. The couple returned to Ottawa, where Olive gradually recovered movement on her left side.45 On January 1, 1976, Diefenbaker was named a Companion of Honour in the Queen’s New Year’s Honours List, becoming one of a distinguished company that cannot exceed sixty-five members. Diefenbaker acknowledged the honour and told reporters that “it is a designation by the Queen herself and not based on a recommendation by the prime minister.” The Globe commented that “Canadians of all political faiths will applaud … With a lesser man than Mr. Diefenbaker there might be reason to worry that this recognition by the Monarch might be a rite of passage from the political melee into the more gentle twilight of mellow nostalgia. But of John Diefenbaker we need have no such fear.”46

When Diefenbaker travelled to London at the end of March for the ceremony of presentation at Windsor Castle, Trudeau injected his own, Diefenbaker-like, note of mischief by dropping the comment that it was he who had recommended Diefenbaker for the honour. The Chief - taking genuine or mock offence: Who could tell? - insisted that the queen had made her own choice, and that Trudeau had done no more than act as formal intermediary to discover whether he would accept.47

For Diefenbaker, the London trip was another memorable interlude. He stayed with his old political opponent and friend Paul Martin, who was now Canadian high commissioner. Despite their long competition, the two had always respected each other for their shared political vocations and talents. He was entertained - or better, he entertained - at a small luncheon hosted by the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, “bantering quietly” with Martin and provoking his hosts to gusts of uproarious laughter with his anecdotes. That evening, Martin held a larger and equally convivial dinner in Diefenbaker’s honour.48 On April 1 he spoke to a lunch of four hundred guests at the Dorchester, telling old stories: “The sort of cracker-barrel stuff Dief has been giving Canadian audiences for years,” reported George Bain in the Toronto Star, “requiring the occasional growl and subtle inflection to put it over, and going over here on Park Lane as it does in Lilac, Sask.” Diefenbaker told his audience of the shortest judgment he’d ever heard, in a civil suit against a man who had made a final plea: “As God is my judge, I am not guilty.” The judge had replied: “He’s not. I am. You are.” And he recalled that he had once been introduced by a Ford dealer in British Columbia who droned on interminably while searching for his name and then, “his eyes brightening like those of a politician who suddenly remembers a constituent,” he announced: “And now, without further ado, I give you John Studebaker.”49

The next day, Diefenbaker talked with Harold Macmillan, Edward Heath, and Margaret Thatcher, and spent “a fabulous evening” at Windsor Castle. Diefenbaker told the press that the queen “laughs at some of my cockeyed stories. And last night she was in an almost ecstatic mood.”50

He was also, good-humouredly, thinking about his own mortality. He commented to a reporter that early in 1975 someone from the Department of External Affairs had come to see him because “they thought I was going to die” and wanted to discuss funeral arrangements. “And I said, ‘Hightail! Get!’ and that’s not regarded as appropriate language in certain circles in External Affairs. I wasn’t particularly enamored of the craving desire to get information about my funeral. Some people had no sense of humor. They thought I was terrible.”51 His visitor - in fact from the secretary of state’s department - was Graham Glockling, the director of special events.

When I took over state funerals as part of my portfolio in Secretary of State, I looked into files and there wasn’t an awful lot there, quite frankly. And I thought, God, this is no way to run a railway or a funeral. So I was chatting to a few people and I said, it’s a pity the incumbent couldn’t have some input into this. A couple of people said, why don’t you try it out for size. I thought, well, Diefenbaker’s the most likely one … So I went over there. He was actually quite tickled at the whole idea … his words were something like, I’m so grateful that the government thinks enough of me to let me have a hand in the planning. I didn’t want to tell him it wasn’t the government, it was me. I just wanted to make my life easier.52

The project was titled Operation Hope Not, recalling the code-name of the planning committee for Winston Churchill’s state funeral. (But Churchill himself was not a participant in the planning, and made only one suggestion: “Remember, I would like lots of military bands at my funeral.” There were nine.53) Diefenbaker and Glockling completed the plan after several months, and Glockling filed it away.

During 1976 Olive partially recovered from her stroke, but she was weak and continued to suffer from the arthritis that had long pained her. In October she was hospitalized with a heart attack, but was released from hospital in December to spend Christmas at home. On December 22 she died. The funeral took place on Christmas Eve at the First Baptist Church in Ottawa, and she was interred in Beechwood Cemetery, beside the plot reserved for John. Another memorial service was held for her at St Alban’s Cathedral in Prince Albert. The many public reflections on her life were warm and heartfelt. The Ottawa Citizen commented: “The serenity which marked her life and death was not a mere social grace. It was a tranquillity born of deep faith combined with extraordinary strength of character. She allowed her example to speak for her, the example of a woman who had no doubts about her role as the wife of a public figure. Her graciousness was the outward sign of the inner confidence, and it was more eloquent than mere declarations of philosophy. She was a radiant lady whose presence illuminated the places where she walked.” The Globe and Mail said: “As the wife of a Prime Minister, she was a graceful and serious enthusiast. As the wife of a politician, she was a staunch and demanding ally. As a woman, she was an unapologetic defender of the value of supportive partnership between husband and wife, and Canadians responded with widespread respect.” The Toronto Star spoke of her “calming influence on her mercurial husband.”54 The comments only hinted at the powerful influence Olive had had on her husband. Her public grace concealed a stern character, more forceful, more austere, more censorious than his own. At first she had been uneasy in her political role, but soon she was his closest confidante and firmest support. Later, in his adversity, she had reinforced rather than allayed his suspicions and his hatreds. For John, the death of this strong and loving partner of twenty-three years was a loss he could never overcome. For months he was in helpless despair, comforted intermittently by his faith.

He was still thinking - more frequently now - of his own approaching death. Aside from some troubled questions about the heavenly arrangements for Edna’s and Olive’s presence beside him, his preoccupations were worldly. He was concerned to set the final building stones of his legend properly in place. In the autumn of 1978 he proposed to his aides that he should be buried not in Beechwood Cemetery in Ottawa, but on the Saskatoon bluffs beside the Diefenbaker Centre, with Olive at his side. He approached Graham Glockling to reopen the file. The new proposal would require substantial fresh planning, including approval from the University of Saskatchewan, declaration of the site as consecrated ground, the transfer of Olive’s remains to Saskatoon, and the provision of a funeral train for the long journey from Ottawa to Saskatoon. The Chief proposed that the train “should stop at some places along the route: Fort William, where my people came on foot from Winnipeg; Winnipeg, where they came in 1813 with the Red River Settlement; Watrous in Lake Centre constituency, as they elected me there in 1940; then Saskatoon.” There were a thousand details besides. Glockling “just went ahead and changed the plans and the rest is history.”55

In the summer of 1976 Joe Clark had replaced Robert Stanfield as leader of the Tory party. Clark was on Diefenbaker’s blacklist as an exponent of the leadership review in 1966, and the Chief’s distaste for him never wavered. But Diefenbaker was also increasingly alarmed by what he saw as the authoritarian and centrist tendencies of the Trudeau government. After some delicate probing by the Prince Albert constituency association about the Chief’s intentions, Diefenbaker let them know in early April 1978 that he wished to stand again for parliament. On April 19 he was nominated at a small convention that was addressed by one of his younger party favourites, the Toronto mayor David Crombie. Diefenbaker delivered a strong speech full of sarcasm towards the Liberal government - and then waited a full year for the general election.56

The Chief had outlasted many of his old Prince Albert cronies. By 1979 Art Pearson, Ed Topping, and Fred Hadley had passed on. Dick Spencer was left to run his campaign, along with Max Carment, Glen Green, and Harry Houghton. This time Diefenbaker imported another young acolyte from Ottawa, Michael McCafferty, who faithfully did his chores and endured the old man’s frequent rages. John Munro, Diefenbaker’s ghostwriter and the prospective director of the Diefenbaker Centre, was also present from time to time. Mary Carment and Lily Spencer managed the committee rooms. Spencer tried to keep Diefenbaker close to home and under careful watch, “so that he could be assisted and protected.” He was often confused and seemed to manage best in short discussions of single issues or in face-to-face encounters with individual voters.

Early in the campaign, disaster struck. During the night of April 13, 1979, Diefenbaker apparently suffered a small stroke, fell from his bed, hit the bedside table, and blackened an eye. McCafferty, hearing the disturbance from the next room, struggled to get him back to bed. Next day he could not rise, and went through spells of jumbled and senseless talk. Dr Glen Green cared for him, and the confusion soon passed. Green and McCafferty told the press Diefenbaker was suffering from flu, had fallen in the night, and would spend the weekend in bed, but a Canadian Press report from Ottawa asserted that Diefenbaker was in a coma and would leave the race. Green vehemently denied the story. Spencer continued his account: “By Monday night Dief had regained normal awareness and began a steady recovery. Diagnosis of the malaise was no longer relevant. Our problem was now a political one. If John Diefenbaker did not recover completely, we would be running a candidate ‘without all his marbles,’ as one reporter harshly put it, or we would be forced to withdraw him, risking incredible damage to his legend.”57

For five days Diefenbaker’s four close friends cosseted and sheltered him from the press and the curiosity seekers, feeding him light foods until one of them complained that “this god-damned squirrel food isn’t enough!” and Diefenbaker himself took “a huge breakfast of bacon and eggs, toast, jam and coffee in the hotel dining room Tuesday morning.” The next day he was out on the street campaigning and putting the lie to all the gossip about a wild and incontinent interlude. He told a press conference he had had “a touch of flu” and a good rest. Now he wanted to talk about Pierre Trudeau again.58

For the rest of the campaign his aides watched him solicitously as he suffered repeated spells of anger, panic, and despair. The campaign did not pick up pace, and the NDP offered a firm and convincing challenge in the person of Stan Hovdebo, a young farmer and teacher. Diefenbaker’s team began to fear defeat and humiliation, and stepped up their advertising under the slogan “Diefenbaker, Now More Than Ever.” At the end they brought in the premier of Alberta, Peter Lougheed, for a crisp final rally attended by - among others - Peter Newman. (“I’m glad he came along,” Diefenbaker commented afterwards.) The rally gave new confidence to the team. Diefenbaker remained tired and distracted: “His shakes had increased. His darting eyes and thin wisps of grey, wavy hair shooting out from above his ears gave him an amazed and comic look.”

On election night the Tory campaign rooms in Prince Albert overflowed with national reporters and television crews, all there to observe Dief’s last hurrah. As Joe Clark’s Conservatives claimed a national minority victory, John Diefenbaker won his own seat for the thirteenth consecutive time, with a majority of more than four thousand votes. Diefenbaker spent the early evening in his committee rooms, and thanked his audience one last time: “If it wasn’t for you, I wouldn’t be here. It’s my last campaign. I really mean that. I’m glad I stayed this time.” Then he went upstairs to his room for a glass of beer with a friend, and declined the usual invitation to a late election-night supper at the Glen Greens.59

Diefenbaker returned to Ottawa for the swearing-in of the new Conservative government in melancholic mood. He was glad to see the Trudeau Liberals gone, but he could not rally much enthusiasm for Joe Clark and his team of young upstarts. Old grudges lasted forever. Flora MacDonald had sat next to him for much of the time in the House after her entry to the chamber in 1972, but he had not spoken a word to her since her firing from the national office in 1966. At the governor general’s garden party following the swearing-in ceremony - where MacDonald had become secretary of state for external affairs - Diefenbaker responded to her efforts at reconciliation: “You! You! He should never have made you foreign minister! Minister of health, perhaps, or postmaster general; but never foreign minister!” He turned and stomped away, never to speak to her again.60

The House did not sit that summer. Diefenbaker returned once more to Prince Albert and came back to Ottawa in the heat of late July. He fussed with further changes in his funeral arrangements and his will, and arranged for a series of formal portraits in the House of Commons and his parliamentary office. On August 1 he wrote to his assistant Keith Martin and his friend Senator David Walker, assigning general responsibility for the funeral arrangements jointly to them and offering his latest thoughts on the display of his open casket at stops along the route of his final journey by train across the nation.61 But he was planning a trip to the Yukon in late August for the opening of the Dempster highway, and in September to the People’s Republic of China. On August 15 he appeared for a whimsical ceremony at the National Press Club to shoot the first ball on a new snooker table. On August 16, 1979, in the early morning, he died alone in his study at home.62

Diefenbaker and Donald Fleming lost the 1948 leadership contest on the first ballot to George Drew, the premier of Ontario. On the platform, from left to right, Diefenbaker, Edna, George Drew, Fiorenza Drew, Donald Fleming.

Diefenbaker maintained his law partnership in Prince Albert, mostly in absentia, with John Cuelenaere and Roy Hall until the mid-1950s. (Saskatchewan Archives: Star-Phoenix Collection)

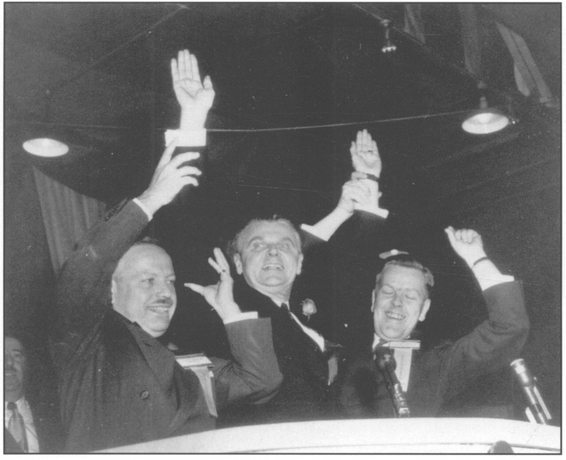

In December 1956 Diefenbaker easily won his third run for the leadership against his parliamentary colleagues Donald Fleming and Davie Fulton, shown here raising the victor’s hands in triumph. (World Wide Photos)

Olive Diefenbaker was at John’s side to celebrate his election as leader of the party. (Canada Wide)

Following the 1957 general election victory, Diefenbaker took three reporters to Lac La Ronge for a day of fishing.

From left: Mark Harrison of the Toronto Star, Diefenbaker, Clark Davey of the Globe and Mail, and Peter Dempson of the Toronto Telegram. (Canada Pictures Ltd.)

On October 14, 1957, Queen Elizabeth II presided over a ceremonial meeting of her Privy Council for Canada before opening parliament that afternoon. (National Film Board)

On April 1, 1958, Elmer and John posed happily as the telegrams poured in after Diefenbaker’s overwhelming general election victory.

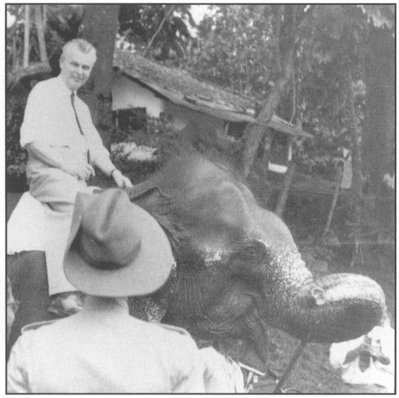

In Ceylon during his 1958 Commonwealth tour, Diefenbaker briefly took a ride on an elephant.

Bringing ashore the marlin, January 1961. This catch became the object of half-serious repartee between President Kennedy and Prime Minister Diefenbaker in February and May 1961. (Roy Bailey)

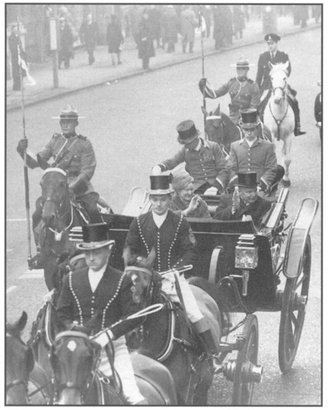

Diefenbaker received the Freedom of the City of London during an early interlude in the 1963 Canadian general election campaign. (Central Press Photos, London)

Diefenbaker turned on the party president, Dalton Camp, to accuse him of betrayal at the 1966 annual meeting of the Conservative Party. At this meeting, the party agreed to hold a leadership convention in defiance of Diefenbaker’s wishes. (Canada Wide)

At Maple Leaf Gardens in September 1967 Diefenbaker made his last stand as leader of the party, challenging the phrase “deux nations” as the translation of “two founding peoples” in a convention resolution.

The House of Commons was not in session when Diefenbaker posed for his last formal portrait shortly before his death in August 1979. (Canadian Press)