Gleaning

There’s nothing quite as satisfying as foraging for free wild food. A handful of nettles for a warming soup, some wild garlic to whizz with olive oil to make a simple pesto, rosehips for a jelly packed with vitamin C? It’s all out there for the picking, even in the city, as long as you know what to look for.

Keep your eyes open and always be prepared with a handy spare bag in your pocket. A stout walking stick can also be very useful to hook a stray branch; you can bet the biggest and best produce is just out of arm’s reach.

Whether in the town or the country, stick to a few basic rules; pick produce well away from the path or road; if there’s only a small amount leave it to grow; never dig up a plant; and, most important, if in doubt don’t pick it! Once at home with your bounty make sure to wash everything thoroughly before you eat it.

Once you’ve been bitten by the foraging bug you’ll be amazed how much wild produce there is around. As the seasons progress new treats constantly reveal themselves. Blackberries climbing over a park fence, a rogue apple or damson tree; another one for the list. All my secret locations are carefully documented in a treasured battered notebook as a reminder for next year. So get out there and get picking: the rewards are huge.

In early spring, when snowdrops raise their nodding headsb, the first optimistic shoots of wild garlic push through the earth. As the days start to warm, the shoots erupt into a bright green carpet of long, pointed leaves, garlanded with delicate white flowers.

A member of the Allium family, wild garlic, or ramson, flourishes in moist wooded areas and is instantly recognizable by – the strong smell of garlic! Once picked the leaves keep well when stored in the fridge, so don’t be shy about how much you take. Remember to pick a posy of the edible white flowers: they make a tasty, pretty garnish for any wild garlic recipe.

After the long winter months wild garlic makes a welcome leafy green addition to the plate; it can be used as a herb or like spinach. Add to soups and bakes, tear into salads or blend to make a robust pesto. For a quick supper stuff chicken breasts with finely sliced leaves and fry in olive oil until golden; or simply blanch handfuls in boiling water and toss in the juices of a Sunday roast. (Just remember that wild garlic wilts considerably when simmered in boiling water.)

Wild garlic can be preserved using the same method as nettles (see page 18).

Perk up pasta with a blast of flavour! Serve with your favourite pasta topped with grated Parmesan cheese or spoon on to soups, baked potatoes or risotto. Pesto stores well in the fridge: just make sure there is always a layer of olive oil on top to seal the pesto from the air. This recipe can also be made with young nettle leaves; add a plump clove of chopped garlic to the ingredients before blending.

2 good handfuls of washed wild garlic leaves

a handful of pine nuts, chopped walnuts or pumpkin seeds

110ml/1/2 cup extra virgin olive oil

a squeeze of lemon juice

a little fresh chilli (optional)

salt and black pepper to taste

Plunge the wild garlic leaves into rapidly boiling water, drain and refresh with cold water. Squeeze any excess water away and blend with the remaining ingredients until finely chopped. Scoop into a sterilized jar, pour a thin layer of olive oil on top and seal with a tight-fitting lid. Store in the fridge until ready to use.

A clear, delicately scented broth topped with wild garlic flowers. Add the wild garlic just before serving, to preserve the flavour and bright green colour of the leaves.

3 young leeks, topped and tailed, washed and thinly sliced salt and black pepper

2 good-sized handfuls of wild garlic leaves, washed and thinly sliced wild garlic flowers to garnish

For the broth

1.5 litres/6 cups good chicken or vegetable stock

1 leek, topped and tailed, cleaned and cut into big chunks

1 medium onion, peeled and quartered

2 carrots, peeled and cut in half

2 celery sticks, cut into large chunks

1 teaspoon black peppercorns

2 bay leaves

1 plump clove of garlic

First make the broth. Pour the stock into a saucepan, add the vegetables, pepper, bay leaves and garlic, cover the pan and gently simmer for 20 minutes.

Strain the broth into a large bowl and return the resulting liquid to the pan. Add the sliced young leeks and seasoning to taste. Cover the pan and simmer until the leeks are soft.

Add the sliced wild garlic. After a few minutes, when the leaves have wilted, the soup is ready to serve. Ladle into bowls and carefully float wild garlic flowers on top.

A forager’s twist on the classic creamy sliced potato bake. The trick to a good dauphinoise is to cut the potatoes as thin as you dare.

4 largish waxy potatoes, peeled and thinly sliced

1 medium onion, thinly sliced

a large handful of wild garlic, well washed and thinly sliced

300ml/1 1/4 cups double cream

150ml/2/3 cup good vegetable stock nutmeg

a small bunch of thyme

salt and black pepper

butter

Preheat the oven to 190°C/375°F/gas mark 5.

Butter a baking dish and line with a layer of sliced potatoes. Sprinkle with a little sliced onion, wild garlic, a good grating of nutmeg, thyme, salt and freshly ground black pepper. Continue to layer the potatoes in this way until all the ingredients have been used up, making sure to finish with a layer of potato.

Pour the stock and cream evenly over the top and dot with the butter. Cover with kitchen foil and bake in the oven for 45 minutes. Remove the foil, turn the oven up to 200°C/400F°/gas mark 6 and bake for a further 20 minutes, until the dauphinoise is brown and crispy on top.

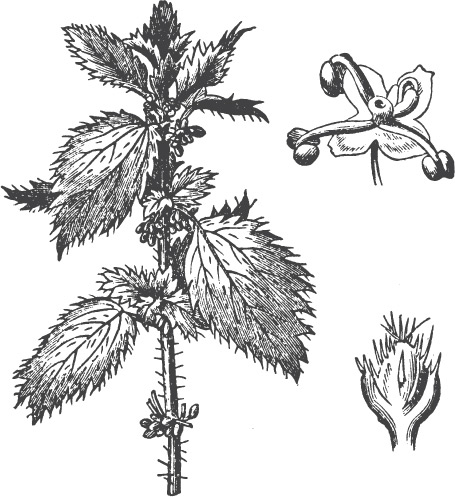

Nettles are everywhere. They just are. The ultimate free superfood packed full of protein, iron, magnesium and vitamins A, C, D and B complex. Their pleasing earthy flavour is making its way on to some of the most fashionable menus.

Nettles are at their best in the spring when the plants are small and the leaves tender; by the summer months they have become too fibrous to eat. Wade into battle armed with a protective gauntlet of rubber gloves and long trousers tucked into wellies. Gather leaves well away from the path, selecting the new growth at the top of the plant: as a basic rule I tend to collect the top four leaves.

Nettles are remarkably versatile. Nettle soup makes a simple nutritious lunch and risotto an adventurous supper. Add a handful of blanched leaves to an omelette batter or ward off hay fever with antihistamine-rich nettle tea; brew a handful of nettle leaves in boiling water for 5 minutes. Dollop nettle pesto on to new potatoes: simply follow the recipe for wild garlic pesto (see page 13), substituting nettle leaves for the wild garlic and adding a plump chopped garlic clove to the mixture before blending.

If you enjoy the taste, prolong the pleasure: blanch washed nettle leaves, finely chop in a food processor and freeze in portions in an ice cube tray. When the cubes are frozen, remove from the tray and store in a sealed plastic bag. Alternatively, blend blanched leaves with oil and store in sterilized jars in the fridge: just make sure the puréed nettles are covered with a layer of oil.

A thick, comforting soup for a spring day. This recipe also works well with wild garlic leaves.

3 rubber-gloved large handfuls of young nettle leaves

a large handful of spinach leaves olive oil

1 medium onion, finely chopped

3 cloves of garlic, finely chopped

3 medium potatoes, peeled and cubed

3 celery sticks, sliced

1.5 litres/6 cups vegetable or chicken stock

nutmeg

salt and black pepper

double cream

chives, to garnish

Thoroughly wash the nettle leaves, wearing rubber gloves. Destalk and slice the spinach leaves.

Cover the bottom of a medium-sized saucepan with olive oil. When hot add the chopped onion and garlic and sauté until translucent. Add the potato and celery and cook until the potato starts to soften.

Pour in the stock, cover the pan and gently simmer until the potatoes are soft.

Add rubber-gloved handfuls of nettles and sliced spinach to the pan. Simmer for a few minutes longer. When the leaves begin to wilt remove the pan from the heat immediately. Take care not to overcook the leaves at this stage or the soup will lose its bright green colour.

Add a good grating of nutmeg and season to taste. Liquidize the soup until thick and smooth.

Serve topped with a swirl of double cream and chopped chives.

It’s stunning how good this bright green risotto tastes. Nettles and risotto rice are simply made for each other.

3 rubber-gloved large handfuls of washed young nettle leaves

3 tablespoons butter

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 small red onion, diced

2 young leeks, cleaned and thinly sliced 400g/2 cups arborio rice

110ml/1/2 cup dry white wine

1 litre/4 cups hot chicken or vegetable stock

75g/1 cup grated Parmesan cheese a handful of chopped parsley a knob of butter salt and black pepper

To garnish

rocket leaves

extra grated Parmesan

a drizzle of olive oil

Drop the nettle leaves into a pan of rapidly boiling water. After no longer than a minute, drain the nettles and refresh with cold water. Blend the leaves in a processor until finely chopped.

In a heavy-bottomed pan, heat the butter and the olive oil. When the butter has melted, add the diced onion and leeks and sauté until soft, but not brown.

Stir in the arborio rice until coated with butter, pour in the white wine and stir until the wine has been absorbed.

Gradually add the hot stock, a ladle at a time, making sure all the stock has been absorbed before adding the next ladle. Stir continually to achieve the perfect creamy risotto.

Add the prepared nettles, grated Parmesan, parsley, a large knob of butter and seasoning to taste. Stir until well combined.

Serve topped with rocket leaves, extra grated Parmesan and a drizzle of olive oil.

Elder bushes are prolific in hedgerows, parkland and embankments. In late spring, as the days start to lengthen, elderflowers burst into bloom, a profusion of creamy white flower heads. Time to get picking – the season is short.

Gather flower heads early in the season, when the tiny star-shaped flowers are open but not dropping. Give the heads a good shake to remove any insects before you add them to your bag.

The heady floral scent of elderflowers adds a delicate flavour to puddings and preserves. The flowers can be tied in muslin and simmered directly with ingredients, or added as a cordial. Cordial preserves the subtle flavour of elderflowers until well after the last flowers have withered. Add it to custards and tarts, milky panna cotta, poached pears, fools and jellies, or dilute with water for a delicious drink.

Don’t forget the copious clusters of deep purple berries rich in vitamin C that follow the elderflowers in late summer. Add them to jams, pies and puds or whizz cooked elderberries in a blender with a little sugar to make a delicious – and eye-catching – fruit coulis. Elderberry cordial, a traditional cure for colds, is very simple to prepare: cover washed berries with water and simmer until soft; sieve the fruit and for every 600ml/2 1/2 cups of liquid collected add 400g/2 cups of sugar, 6 cloves and the juice of a lemon. Briskly simmer for a further 10 minutes and decant into sterilized bottles.

The quickest way to remove the berries from the stalk is to run the stalk through the prongs of a fork. Once picked the berries have a short shelf life: store in the fridge or freeze whole until ready to use.

Light and fragrant, elderflower cordial diluted with sparkling water makes a thirst-quenching summer drink. if you prefer something a little stronger, mix the cordial with vodka, soda, a squeeze of lime juice and a sprig of mint. To decorate and cool your glass, freeze tiny elderflowers in ice cubes. Stored in the fridge the cordial will keep for six weeks or so. For a longer shelf life freeze it in ice cube trays; place the frozen cubes in sealed plastic bags.

MAKES ABOUT 1.5 LITRES/6 CUPS

20 elderflower heads

3 limes

1.5 litres/6 cups water

800g/4 cups caster sugar

Pick flowers that are open but not dropping. Cut the stem off with a pair of scissors, wash the flowers and place in a large saucepan.

Squeeze the limes, add the skins to the saucepan and set the juice to one side. Add the water to the pan, cover and bring to the boil. Reduce the heat and gently simmer for 10 minutes. Remove the pan from the heat and leave to stand for half an hour.

Strain the liquid through a scalded jelly bag or muslin-lined sieve into a clean saucepan. Add the caster sugar and lime juice and stir over a low heat until the sugar has dissolved. Turn up the heat and fast boil for 5 minutes.

Decant into sterilized bottles while still hot; seal immediately.

To make this refreshing icy treat, dilute 1 part elderflower cordial to 2 parts still mineral water in a freezer-proof tub. Add lime juice and zest to taste, cover the tub and place in the freezer. After 2 hours stir with a fork to break up any crystals of ice that have formed. Return the tub to the freezer. Repeat the stirring process 2 or 3 more times, until the granita has the consistency of crushed ice, then leave to freeze completely. To serve, allow the granita to defost a little, then pour into glasses and add a dash of vodka, some fresh mint leaves and a few freshly picked elderflowers.

For this quintessentially English pudding – with a difference – combine elderberries with other seasonal berries and currants. To complete the experience, smother with double cream. The fruit compote in this recipe can also be layered with trifle sponges, custard and whipped cream to create a good old-fashioned trifle. You will need a medium-sized pudding bowl.

200g/7oz prepared elderberries

350g/12oz raspberries

175g/6oz blackberries

175g/6oz redcurrants

(or mixed berries and currants of your choice)

2 tablespoons water

caster sugar

8 medium-cut slices white bread (large loaf size)

Place the berries in a saucepan with the water and caster sugar to taste. Gently simmer for a few minutes until the sugar dissolves and the berries split to release their juice. Take care not to overcook the fruit.

Cut the crusts from the bread and line the pudding basin. Start by placing a slice of bread in the bottom of the bowl, then position overlapping slices around the edge. Fill any holes with smaller pieces of bread – there must be no gaps. Keep some bread aside to top the pudding.

Spoon the fruit into the bread-lined basin, reserving a few tablespoons of juice for later. Cover the fruit with overlapping bread slices. Place a saucer small enough to fit inside the bowl on top of the pudding and put a heavy weight on top of the saucer: this is essential to compact the pudding and push the juices into the bread. Keep the pudding in the fridge overnight to give the alchemy time to work.

Remove the weight and saucer just before serving. Run a palette knife around the edge, place a large plate over the top of the bowl and carefully turn the pudding out on to the plate. Use the reserved juice to cover any bits of bread that are not completely soaked. Don’t worry if it collapses a little!

HEDGEROW JAM

A combination of elderberries and blackberries makes a superb dark purple jam (you can also throw in peeled, cored, diced apple if you have a glut).

For every 450g/1lb fruit you will need 350g/1 3/4 cups granulated sugar and the juice of a lemon.

Simmer the fruit with a little water (just enough to stop the fruit sticking), until it starts to break down. Add the sugar and lemon juice and stir over a low heat until all the sugar has dissolved. Turn up the heat and boil briskly until the setting point is reached (see page 9). Ladle the hot jam into sterilized jars, cover with waxed jam discs and seal immediately.

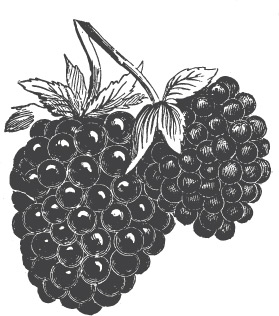

Childhood memories of purple-stained fingers, snagged cardigans and scratched arms always flood back when I am picking blackberries. My lovely mother was an enthusiastic gatherer of blackberries and late summer family outings were always a thinly disguised opportunity to get us all helping with the task. We were easily bribed with the promise of a picnic lunch and the rewards were always worth the effort. Crumbles and pies, jams, jellies and fruit cheese soon filled the table.

Picking blackberries is now, for me, a labour of love. Thankfully, these scented, sweet and juicy, deep purple fruits are hard to miss. Their arched stems vigorously tangle through hedgerows, woodlands, wasteland, parks and ditches. Filled to the brim with vitamins, folic acid and antioxidants, blackberries have supplemented our diet for thousands of years. Add a handful to porridge or muesli or purée and serve with yoghurt.

Harvest the blackberries when they are plump and soft but do not collapse to the touch (it is best to use a solid-bottomed tub or basket as blackberries crush under their own weight). Keep in mind that the berries growing in full sun are usually the sweetest. Creepy-crawlies love blackberries, so make sure to soak the berries in water for half an hour before thoroughly rinsing. Store washed berries in the fridge or freeze until you are ready to use them.

Any surplus blackberries can be used to make blackberry vinegar. Mix into salad dressings, sprinkle on strawberries or add a dash to a cup of hot water and honey for an age-old cold remedy.

MAKES ABOUT 600ML/2 1/2 CUPS

450g/1lb washed blackberries

2 tablespoons golden caster sugar

600ml/2 1/2 cups red wine vinegar

Place the blackberries in a sterilized Kilner jar, sprinkle with the caster sugar and top with the vinegar. Seal the jar and store in a dark place for 4 weeks, rolling the jar a couple of times to help the sugar dissolve. Strain the vinegar, pour into sterilized bottles and seal immediately.

BLACKBERRY AND RARE ROAST BEEF SALAD

Blackberries are particularly good with beef, game or lamb. This recipe is an excellent way to use up any leftovers from a Sunday roast.

blackberry vinegar

olive oil

walnut oil

grainy mustard

salt and black pepper

blackberries (around 10 per person)

port

rocket and watercress

thickly sliced rare roast beef

chopped walnuts

Whisk one-third part blackberry vinegar, one-third part olive oil and one-third part walnut oil with a little grainy mustard. Season to taste.

Poach the blackberries for a couple of minutes in a splash of port. Remove the blackberries with a slotted spoon and set to one side. Add the remaining port to the dressing.

Top spicy rocket and watercress leaves with thick slices of rare roast beef. Sprinkle with the chopped walnuts and poached blackberries and drizzle with the dressing.

BLACKBERRY AND APPLE ALMOND-CRUSTED PUDDING

BLACKBERRY AND APPLE ALMOND-CRUSTED PUDDING

My favourite childhood pudding. I still treasure the original juice-splattered recipe written in my mother’s sloping handwriting. These days I have less of a sweet tooth and tend not to sweeten the fruit, but you can add sugar to taste. Serve with lashings of thick custard.

For the fruit filling

350g/12oz washed blackberries

450g/1lb sweet apples

1 teaspoon vanilla extract golden caster sugar

For the almond crust

75g/1/2 cup self-raising flour

75g/3/4 cup ground almonds

50g/1/4 cup soft brown sugar

50g/1/2 stick soft butter

110ml/1/2 cup single cream or whole milk

a handful of flaked almonds

Preheat the oven to 190C°/375°F/gas mark 5 and butter a deep pie dish.

Check the blackberries to make sure there are no stalks still attached.

Peel and core the apples, cut into chunks and simmer with a splash of water (just enough to stop the apples sticking) until they are soft but not breaking down. Add the vanilla extract, sugar to taste and blackberries. Cook for a couple of minutes, until the juice starts to run from the blackberries. Spoon the mixture into the prepared pie dish.

Mix the flour, ground almonds and sugar together. Cut the butter into small pieces, add to the flour mixture and rub in until breadcrumbs form. Pour in the single cream and combine together to make a stiff mixture.

Spoon dollops of the mixture on to the cooked fruit, to give a cobbled effect. Sprinkle with flaked almonds.

Place the pudding on a baking tray and bake in the preheated oven for 30 minutes until golden brown.

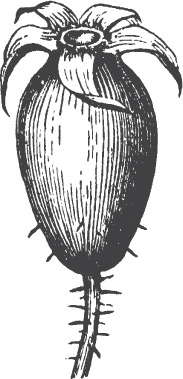

During the autumn months rosy red rosehips, the bountiful fruit of the pale pink wild rose, whose thorny branches clamber unchecked through our hedgerows, are ripe and ready to pick. Rich in vitamin C and antioxidants, rosehips are just too good to pass by.

Pick preferably after the first frost, when the rosehips are soft to the touch but not squidgy. Watch out for the bushes’ snagging thorns and don’t be tempted to taste the hips whole: rosehips contain hairy seeds that are used in the manufacture of itching powder. Use scissors to top and tail the rosehips, and remember to cook them in a stainless steel or enamel pan (they would corrode a reactive pan).

Moreish rosehip syrup is famous for keeping colds at bay. Rosehips also make a good tangy fruity jelly and a vitamin C boosting tea; roughly chop a small handful of hips and infuse in hot water for 5 minutes before sweetening with a spoonful of runny honey.

Rosehip syrup doesn’t have to be limited to medicinal uses. You can pour it over ice cream or pancakes, add it to a stiff vodka and tonic or mix with sparkling water for a tart teetotal cordial. Store the syrup in sterilized screw-top bottles. I recommend using smallish bottles as the syrup has a short shelf life once the bottle is opened.

MAKES ABOUT 1.5 LITRES/6 CUPS

900g/2lb washed rosehips

2.25 litres/9 cups water

450g/2 1/4 cups white granulated sugar jelly bag or muslin square

Top and tail the rosehips and roughly chop in a food processor.

Bring about 1.5 litres/6 cups of the water to the boil, add the chopped rosehips and bring back to the boil. Remove the pan from the heat, cover and leave to stand for half an hour.

Strain the mixture through a scalded jelly bag or muslin-lined plastic sieve. Squeeze the bag to remove all the liquid and set to one side.

Return the pulp to the pan with the remaining water, bring to the boil, remove from the heat, cover and set aside for a further half hour. Strain once more.

Combine the strained liquids in a clean pan, add the sugar and stir over a low heat until dissolved. Simmer the liquid until it has a syrupy cordial consistency.

Decant into sterilized bottles and screw down the tops immediately.

A beautiful clear fruit jelly, perfect to spread on hot buttered toast, or serve with cheese or a Sunday roast. Rosehips are low in pectin, so it is a good idea to add apples to aid the set of the jelly. Roughly chop the whole apple (the skin and core contain valuable pectin); if you have a supply of crab apples or quince even better. To make blackberry jelly, replace the rosehips with the same weight of berries.

MAKES ABOUT 3 X 450G/1LB JARS

450g/1lb rosehips

900g/2lb apples, crab apples or quince

zest and juice of a lemon

jam sugar

Wash the rosehips and apples. Roughly chop the rosehips in a food processor and quarter the apples. Place in a stainless steel pan and add the lemon zest and juice and enough water to just cover the fruit. Cover the pan and simmer until the apples are really soft. Remove from the heat and allow to stand for 20 minutes.

Strain the liquid through a scalded jelly bag or a muslin-lined sieve placed over a large, deep bowl. Ideally, leave the mixture overnight to ensure all the extracted liquid has drained from the pulp. Resist any temptation to squeeze the bag – if you do this you’ll get a cloudy jelly.

Measure the extracted liquid and, based on the proportions of 450g/2 1/4 cups jam sugar to 600ml/2 1/2 cups juice, measure the quantity of sugar required. Combine the liquid and sugar in a stainless steel pan and stir over a low heat until the sugar has dissolved. Bring to boiling point and briskly simmer for 15 minutes or so, until the setting point is reached (see page 9).

Ladle into sterilized jars, cover with a waxed jam disc and seal immediately with a tight-fitting lid.

Whiling away a winter’s afternoon at the local pub’s annual sloe gin competition was not only a lot of fun, but also the perfect opportunity to seek out the judges’ criteria for a prize-winning sloe gin. Chatting with fellow contestants over a pint proved to be an invaluable source of information as well. Treasured recipes, handed down through generations, were swapped and hastily scribbled on the back of beer mats. By the end of the day third prize for the best sloe gin was proudly sitting on my mantelpiece. With all my gleaned tips, hopefully it will be joined by first prize next year.

If you are not familiar with sloes, they are the plump deep purple fruit of the blackthorn tree, a little similar in appearance to a blueberry. The similarity ends there: unlike blueberries, raw sloes have a bitter astringent taste and a hard central stone. But over the centuries such an abundant hedgerow crop proved too valuable to ignore: the result of our ancestors’ experiments is a plethora of recipes transforming the bitter sloe into a delicious treat.

Gather sloes in the autumn when they are ripe and soft to the touch, taking care to avoid the trees’ sharp long thorns. The traditional advice is to wait until after the first frost, which sweetens the fruit. But wait too long at your peril: birds love sloes. And popping the harvested fruit in the freezer has the same sweetening effect.

If gin isn’t your thing, how about an unusual autumnal dark red jam? Sloes are low in pectin, so it’s a good idea to combine with apples to help the set.

MAKES ABOUT 3 X 450G/1LB JARS

450g/1lb sloes

450g/1lb apples

900g/4 1/2 cups jam sugar

Wash the sloes and remove any stalks. Roughly chop the apples (peel, stalks and core included).

Place the fruit in a large pan with a splash of water (just enough to stop the fruit sticking) and simmer until the fruit is soft and breaking down.

Sieve the fruit and return the resulting purée to the pan with the jam sugar. Place on a low heat and stir together until all the sugar has dissolved.

Bring to the boil and continue to rapid boil until setting point is reached (see page 9).

Ladle the hot jam into sterilized jars, cover with a waxed disc and seal immediately.

The secret to an award-winning sloe gin is to keep the amount of sugar added to a minimum. It is also crucial to mature the strained nectar for as long as you can bear. The winner’s sloe gin hadn’t seen the light of day for two years.

It is traditional to prick the skin of every sloe with a pin or fork before covering with gin. The cheat’s method is to freeze the sloes overnight: this splits their skins and once defrosted they are ready to use.

No self-respecting sloe gin enthusiast discards the resulting gin-soaked fruit. The precious berries are traditionally added to still scrumpy cider to make the delectable ‘slider’. If this sounds too lethal, the berries can be sieved to make a boozy fruit purée. Alternatively, coat the whole berries in dark chocolate: just watch out for the stones!

A tot of sloe gin warms the soul in winter and mixed with an equal measure of standard gin, a good squeeze of lemon and a dash of soda it makes a summer party go with a swing.

You will need a sterilized Kilner jar (roughly 2kg/4lb capacity)

MAKES ABOUT 725ML/3 CUPS

450g/1 lb ripe sloes

175g/3/4 cup granulated sugar

725ml/3 cups gin

Wash and de-stalk the sloes.

Puncture a handful of sloes with a fork; or freeze them overnight and defrost before using.

Place the sugar in the sterilized Kilner jar, add the prepared sloes and pour the gin over the top.

Seal the jar and store out of direct sunlight for three months. Turn the jar every few days to dissolve the sugar and combine the flavours.

After three months, strain the sloe gin, reserve the fruit and decant the liquid into sterilized bottles. Stopper the bottles securely and label them with the vintage date.

Leave the sloe gin to mature for at least three months before drinking.

Place the gin-soaked sloes in a sterilized Kilner jar and pour over 1 litre/4 cups of still scrumpy cider.

Seal the jar and leave in a cool dark place, turning regularly, for a couple of weeks.

Strain the slider, retaining the sloes once more (to make sloe purée) and decant into sterilized bottles. The slider is ready to drink immediately. I wouldn’t recommend keeping it too long.

AND FINALLY SLOE PURÉE

Place the sloes in a stainless steel saucepan, barely cover with water and simmer until the berries are soft and starting to break down. Pass small portions of the cooked sloes through a sieve, with the aid of the back of a wooden spoon, a firm hand and a little patience. Make sure only the skins and stones are left in the sieve and none of the valuable flesh is discarded. (A mouli, if you have one, makes light work of this job.) Mix the sieved purée with a dash of sloe gin and clear honey. Store in the fridge or freeze in small portions until ready to use. The purée is superb mixed into trifles, crumbles, jam and cake mixtures, or served warm as a fruity accompaniment to game.

Dainty fairy cakes with a hidden tipsy heart.

MAKES 12

110g/1 stick soft butter

100g/1/2 cup caster sugar

2 medium free-range eggs

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

110g/3/4 cup self-raising flour puréed gin-soaked sloes

To serve

icing sugar and crème fraîche or clotted cream

Preheat the oven to 180°C/350°F/gas mark 4.

Prepare your cake tray by placing 12 paper cake cases in the indents of a 12- hole tart tray.

Cream the butter and caster sugar together until the mixture is very light and fluffy.

Beat in each egg one at a time.

Beat in the vanilla extract.

Carefully fold in the flour until all is well combined.

Two-thirds fill the prepared cases with cake mixture. Make a small indent in the top of each one and spoon in 1/2 teaspoon of the sloe gin purée.

Bake on the middle shelf of the oven for 15-18 minutes, until golden brown. The cake should spring back when lightly pressed in the middle.

Dust with icing sugar and serve with crème fraîche or clotted cream.