Simply put, stress is a state of readiness. It is the mind’s and the body’s way of rising to an occasion and preparing you to do your best. Although the effects of too much stress can be debilitating, stress itself is a completely natural and necessary response, one experienced by all humans and animals.

Stress is not—repeat, not—a mental illness. Just as people’s heights vary over a wide range from short to tall, people’s everyday stress levels vary over a wide range from relaxed to “stressed out.” Stress, no matter how extreme, will never make you “go crazy.”

Stress is a natural occurrence and has a very useful function. Let’s say, for example, that you were going to be a contestant on a television quiz show. If you felt no stress at all, you may not prepare for the show, and as a result might do poorly. If, however, you felt extremely stressed, you may be too nervous to study and could become confused and distracted when the cameras started rolling. But if you felt a mild amount of stress, you would prepare well in advance, concentrate better, and react faster when the questions were asked. The physical and mental responses that constitute stress are useful if they happen occasionally and in moderation. But if they happen all the time, day in and day out, they can have unpleasant effects.

Experiencing a high level of stress for a long time can cause you to lose sleep, feel constantly fatigued, have trouble concentrating, and respond irritably to those around you. Long-term stress can also cause headaches, skin irritations, ulcers, diarrhea, and pains at the base of the jaw (temporomandibular joint [TMJ] syndrome). Stress can interfere with sexual function, inhibiting both desire and ability. Research also shows that long-term stress may increase your chances of later developing heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, or immune system problems.

Although this list may look intimidating, you should not add to your stress by worrying about health problems. Being highly stressed does not mean that you will get diseases, merely that you may increase your susceptibility over time. Clearly, reducing stress can have important benefits, both mentally and physically.

If you are reading this book, you may be wondering why other people do not seem to be as stressed as you. Stress is not a disease, nor a sign of weakness. Feelings of stress come from a combination of two different sources: the world around you and your way of dealing with that world. These two sources, the environment and your personality, interact to produce your actual levels of stress. Sometimes your life can be filled with so many stressful events that it is no wonder you feel overwhelmed. But stressful events are not enough. We all know of people who don’t seem to become flustered no matter how difficult the situation. These “cool customers” seem to have personalities that can deal with any situation, no matter how tough. On the other hand, there are some people who seem to make “mountains out of molehills” no matter what the situation. For these people, no matter how small the event, it still seems that they will make themselves stressed.

But personality is not the whole story. Different situations vary in how stress provoking they are. The more difficult the situation, the more people you will find who become stressed and the more stressed these people become. So you can see that in any situation, the degree of stress you will feel depends on a combination of the type of event happening at the time (how stress provoking it is) and the way you respond to or deal with that event (your personality). Therefore, to change your stress levels, you can either change the world around you or change the way you respond to that world, or both. Surprisingly, it is often easier to change your own responses than to change what goes on around you. However, it is also quite often possible to do the latter.

In this program we will be teaching you to consider both parts of the stress response. In the first part of the program (Steps 2 through 5) we will teach you different ways of coping with the world around you—for example, modifying your personality. In the second part of the program (Steps 6 through 8), we will talk about ways in which you might actually change your environment to make it less challenging. Let’s discuss these sources of stress in more detail.

We all know that there are lots of things in our world that can make us stressed. Usually we think of the big things—losing a job, death of a partner, a serious car accident, or approaching deadlines. True, these are all events that, when they occur, can make us very stressed. But we also need to remember what scientists call “daily hassles.” These are many of life’s more general, smaller events that are annoying, irritating, and unpleasant and can be an ongoing source of stress. Some examples of daily hassles might be heavy traffic on the way to work, an unpleasant work colleague, noise around the home, or an overdependent relative. In fact, because they are so common and tend to add up, daily hassles are often more of a problem for most of us than major life events. It is important also to remember that positive things can sometimes be stressful because of the negative aspects that go with them. For example, going on a vacation can actually be a major source of stress because of the organization and extra work you have to do to get away. Finally, the circumstances of our lives can be constant and ongoing sources of stress. Some of these are things we can’t do much about, such as being poor, having an abusive parent, or living in a high-crime area. Others have a lot to do with our choices in life, such as trying to raise three children and have two jobs, working for a company that demands too much, or struggling to pay off that expensive vacation that you really couldn’t afford.

The way we cope with stressful events like those described above is really a part of our personalities. As with any personality characteristic, your general stress level has two major components: genetics and environment. Researchers are still trying to pinpoint the exact genetic component to stress. What is most likely is that there is no specific stress gene. Rather, if you are a highly stressed person, you may have inherited a tendency to be generally emotional. In other words, you may find that you are more sensitive and generally emotional than many other people you know. On the negative side, this means that you will respond to challenges with higher levels of stress. But on the bright side, this tendency probably makes you a sensitive and caring individual. The genetic factor, of course, only means that you may be predisposed to feeling stressed—it does not mean that stress is inevitable. Even if you have a genetic predisposition to stress, you can learn to manage it.

Much of your personality probably comes from your environment, from things that you have learned over the course of your life. These things may have been learned from your parents or from the circumstances and experiences of your life. These lessons vary from person to person, and we can’t necessarily describe them here. But we do know that people who feel high stress in a lot of situations tend to have two major beliefs:

1. They believe that their world is full of negatives.

2. They believe that they don’t have as much control as they would like over the negatives in their lives.

If you can identify with these beliefs, just remember that it took you a long time to learn them. You are not going to unlearn them overnight. But with hard work and practice, your outlook can change. We will not be looking into your past to try and determine what caused your original tendency toward stress. You will not be expected to regress back to your childhood or to blame your parents. Instead, you will be learning practical skills to help you control stress here and now. If you cannot identify with these issues at this point, don’t worry. We will discuss them in more detail in a later chapter, and we hope that you will find that they begin to make more sense.

When you perceive a potential threat or challenge, your mind and body prepare you to deal with it. The danger does not have to be real; anything you perceive as a threat or challenge triggers your body and mind to get ready. Actual physical threats are not the only trigger. Potential failure or ridicule is a major source of stress for most people.

Let’s consider an example. Imagine that you are walking home at night and your route takes you down a deserted lane. As soon as you enter the lane, you are on alert. Your mind and body are preparing themselves to take action in the event you are confronted with danger. Though it may not be immediately apparent, the purpose of stress is to protect you. If a mugger suddenly jumped from the shadows in the lane, you would be physically ready to respond quickly.

The challenge of deadlines provides another common example. When you have an important report due in an hour and you haven’t finished it yet, you feel stress, in this case because of the potential failure that is involved if you don’t finish the report. When your sister is coming to pick you up in a few minutes and your children are screaming and you haven’t had time to take a shower, you feel stress.

In both of these cases, the threat is not the deadline itself. It is the fear that you will fail and that someone important to you, your boss or your sister, will criticize you for letting them down. If you cared nothing about these people, you would not have these stressful feelings. But most of us do care; therefore, most of us would feel stress in similar situations. This shows how the environment (approaching deadline) interacts with your personality (caring about your boss’s opinions) to produce your level of stress. The closer the deadline, the higher your stress. In the same way, the more you care about your boss’s opinion, the higher your stress. Your final level of stress, then, will depend on a combination of the environment and your personality.

Stress is a response to some sort of potential negative that we perceive in our environment. The word “stress” is a broad, poorly defined term that we use to refer to a large range of responses to negatives. When you perceive a situation as having some potential negatives, you attempt to deal with that situation and eliminate the negative. If you do this successfully, you feel positive emotions. But if the situation is beyond your ability to cope, you experience a range of negative reactions that are broadly labeled “stress.” The various emotions you might experience include anger, anxiety, and depression. When you experience these feelings, your mind and body will react in certain ways. These are described below.

The physical or physiological response system includes all the changes that take place in your body when you are stressed. Some of these changes can seem quite bizarre and frightening when they are unfamiliar. But rest assured that they are all natural, important, and, in the short term, harmless. However, if stress is maintained for long periods, your body’s immune system can begin to break down, leaving you more susceptible to developing diseases.

When you perceive or anticipate a threat, your brain sends messages to a section of your nerves called the autonomic nervous system. This system has two branches, the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Simply stated, the sympathetic nervous system releases energy and gets the body primed for action. Later, the parasympathetic nervous system returns the body to a normal state.

The sympathetic nervous system releases two chemicals, adrenalin and noradrenalin, from the adrenal glands on the kidneys. Fueled by these two chemicals, the activity of the sympathetic nervous system can continue for some time.

Activity in the sympathetic nervous system makes your heart beat more rapidly and your blood flow much faster and differently. By tightening your blood vessels, your sympathetic nervous system directs blood away from places where it is not needed, such as skin, fingers, and toes, and moves it toward places where it is needed more, such as your arm and leg muscles. For this reason, when you experience extreme stress, your skin may look pale and your fingers and toes tingle or become numb. Meanwhile, the value of this effect for your survival is that the blood flow has primed your large muscles for action.

The rapid heart rate and fast breathing you experience when under stress help to provide more oxygen to your body. Although this is important for fast action, the change can make you feel as if you are choking or smothering, and may cause chest pains. In addition, the reduced blood supply to your head can make you feel dizzy or confused, causing blurred vision or a feeling of unreality.

Overall, stress affects most of the systems in your body. This process takes a lot of energy, which explains why you feel drained at the end of a stressful day. It is important to know, however, that your sympathetic nervous system cannot get “carried away” and leave you in a state of “high stress” indefinitely. Your body has two safeguards to prevent this. First, other chemicals in the body will eventually destroy the adrenalin and noradrenalin released by the sympathetic nervous system. Second, the parasympathetic nervous system is a built-in protector. When your body has “had enough” of the stress response, the parasympathetic nervous system will kick in to restore a relaxed feeling. This may not happen as quickly as you would like, but it will happen. Your body will not allow your stress to keep increasing until you “explode.”

In addition to the effects on your autonomic nervous system, feeling stressed produces a release of chemicals from your pituitary gland (a small area at the base of the skull). These chemicals travel to another section of your adrenal gland to release various corticoids and steroids that help to reduce swelling and inflammation. If stress is prolonged, the constant release of these chemicals can also produce some damage to your body (e.g., in the circulatory system) and make you more susceptible to disease.

The physical responses that prepare you for action, as well as those involved in calming you down, are largely automatic. You cannot eliminate them altogether, nor would you want to. As we have said before, stress serves an important protective function. It can lead to greater accomplishment and even, under the right circumstances, be enjoyable. In the short term, stress is not harmful, and small amounts of stress can actually have some benefits. But if you experience high levels of stress for long periods of your life, you may be more likely to have physical problems. Obviously, learning to control your stress is important for many reasons.

Your body is not alone in preparing for action when you face a challenge or threat. Your mind also gets into the act. The major mental, or cognitive, response is to change your focus of attention. When you are under stress, you tend to scan the environment constantly, looking for signs of threat. On one hand, this shift in attention is useful; if danger exists, you will notice it quickly. On the other hand, you may feel easily distracted and unable to concentrate on any one thing.

As part of this scanning process, your mind considers all the possible outcomes of a threatening situation. In other words, you have a lot of anxious thoughts or, as most of us would put it, you worry. Worrying is one of the main characteristics of people under stress. A little worrying is normal; everyone does it. Many of us worry about the same kinds of things. But people who are continually stressed have trouble turning off the worrying. Sometimes they even feel they need to worry, fearing the lack of worrying might be irresponsible. Try to avoid falling into this trap! Being responsible is an admirable goal. But if you have reached the point where the thoughts churning through your head are keeping you awake at night, worrying is not helping you. In fact, it’s hurting you. We will be teaching you ways of controlling your worry later in this program.

Let’s apply these components of the mental response to our example of walking through a dark lane. As you walked, you would literally be scanning, looking and listening for possible danger. If there were a sudden noise, even from a harmless stray cat, you would most likely jump. But if a mugger appeared, you would probably spot him quickly. The worrying in this case might take the form of questions running through your mind: “Is he going to hurt me?” “Does he have friends around?” “Does he have a gun?” To some extent, this worrying is useful; it prepares you for the possibilities.

In the example of the late report, you would probably concentrate hard on the task at hand. In this situation, your focus would not be on scanning, but chances are you would still be worrying, asking yourself: “What if I don’t finish on time?” “What will my boss say?” “What would I do if I lost this job?” These worries may be useful if they remind you of how important the task is. But if the worries become so great that they interfere with your ability to finish the report, you may have started a vicious cycle. Worrying could make you miss the deadline, which would cause you to lose confidence in yourself. Without confidence, you may miss the next deadline, and then you would feel even more stressed than you did before. Obviously, you do not want to let worrying go this far.

Stress is also likely to influence some of the ways you behave. You may act irritably, or you may start to avoid situations that you fear could be stressful. In fact, to return to our first example, you would probably avoid the lane entirely if you thought it looked dangerous—in which case stress and the anticipation of danger would actually have protected you. On the other hand, in our deadline example, avoiding the report (or procrastinating) shows how stress can really interfere with tasks.

Many people get jittery when they are under stress. You are probably familiar with your own nervous habits: pacing, tapping your feet, biting your nails, smoking, or snacking. Whatever your habit is, you will probably notice yourself doing more of it when you are under stress. Most of these behaviors are simply ways of letting off some of the energy that has built up from your physical and mental preparation for action. Still others (such as escaping from or avoiding unpleasant situations) are there to protect you. The rest may be individually learned ways of trying to calm down.

As with the other response systems, these behaviors are generally harmless and may even be beneficial when realized in moderation. But they can become excessive and begin to interfere with your enjoyment of life. Importantly, when avoidance becomes severe it can make you miss important opportunities, which can lead to even more stress.

The physical, mental, and behavioral response systems each have their own purposes. But they also interact closely. Any one system can trigger the whole spiral. For example, you may notice your heart beginning to pound. This, in turn, could trigger thoughts that something is wrong. You begin to pace nervously back and forth. Alternately, you may begin with a worrisome thought about the children that may cause your body to react and then make you want to rush home to check on them. Because each system plays a role in the entire stress response, it is important to learn to control each one. This is what our stress management program will help you do.

At the physical level, you will learn to recognize tension in your body before it becomes excessive, and you will learn strategies to help you relax. To address the mental component of stress, we will teach you more realistic ways of thinking about situations so that they do not seem as threatening. Finally, at the behavioral level, you will practice new ways of responding to situations. You will learn through experience that threats may not be threats at all, or they may not be as bad as you fear. Using these techniques will help to teach you new ways of coping with your environment. In addition, at various points in the program, we will describe ways in which you might try and actually change your environment to make it less stress provoking for you.

Now that you understand the way that stress operates in general, it is time to find out more about your own personal experience of stress. What situations lead to stress for you? How does stress affect your body? What goes through your mind when you are stressed? And how do you behave?

You may feel that you can answer some of these questions easily. Or you may not know the answers at this stage. Either way, the first step of managing stress is to understand your own personal triggers and reactions better. The best way to do this is to keep records. Records are important for several reasons:

1. Identifying triggers

The things that cause stress are known as “triggers,” and they are different for each of us. Some of them are large, life-changing events like those noted below. Others are everyday occurrences, minor hassles that might not bother others but that are legitimately stressful for you.

When you do not know what is causing your stress, the responses of your mind and body can seem frightening and unexplainable. Keeping records will help you to identify your stress triggers, thus giving you a greater sense of control.

Triggers that may cause stress include:

• Getting married

• Work deadlines

• Death of close friend or relative

• Having a baby

• Changes in work roles

• Break-up of a relationship

• Financial pressures

• Home repairs

• School examinations

• Car maintenance

• Changing jobs

• Legal matters

• Car accident

• Job interview

2. Gaining objectivity

None of us know all there is to know about our own physical and emotional responses. For example, you may think that on any given day, you are either stressed or not, all or nothing. In fact, you probably experience many degrees of stress.

Keeping records will help you to identify the various ways that you react to stressful situations. You may also begin to realize that more of your physical responses are connected to stress than you might have thought. Keeping records of these responses helps make the whole process more understandable.

If you keep honest records, you are more likely to practice each technique as recommended. You will also be able to give yourself credit for what you have accomplished.

4. Learning skills

Writing out the details in a structured way helps you to understand how each technique works and how it affects you.

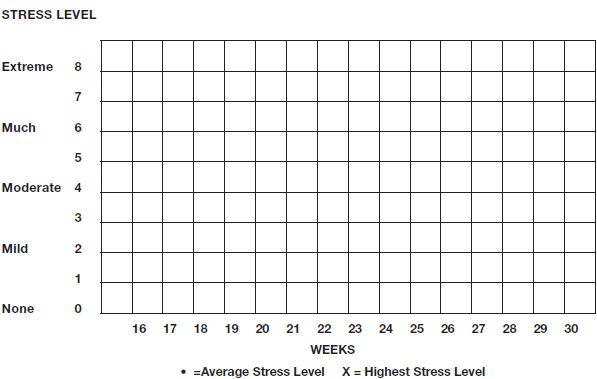

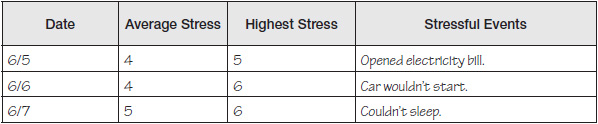

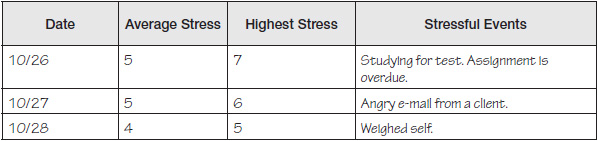

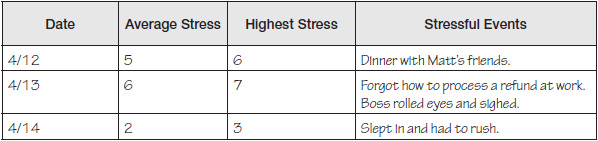

The three forms that follow—the Daily Stress Record, Stressful Events Record, and the Progress Chart—will help you to understand your own stress. We recommend that you complete these for the next two to three weeks, or longer if possible.

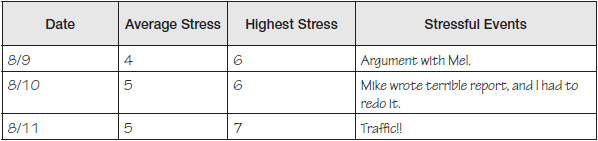

The first form is the Daily Stress Record. You may wish to prepare your own version of the form, or take the one we have provided and print it. Then, every evening, sit down with the form and think back over your day. How stressful was it? You will be recording three things in particular:

1. Your average level of stress during the day

The average level means the overall, background level of stress you felt during the day as a whole. Was it a “good day” during which you felt fairly relaxed most of the time? Was it a “bad day” during which you were constantly tense? Or did the day fall somewhere in between?

You will notice that we ask you to keep this record using a scale from 0 to 8, where 0 is no stress and 8 is extreme stress. We will be using this 0–8 scale at many points throughout the program. It is important that you grow familiar with it and practice assigning your responses to some point along the scale.

![]()

2. The highest level of stress you experienced during the day

If nothing significant happened during the day and you did not become more stressed than your average level, the numbers in the first two columns will be the same. It is likely, however, that your stress level increased in response to at least a few things, small or large, that happened. Using the 0–8 scale, write down the number that best corresponds to your highest stress level of the day.

3. Any major stressful events that happened during the day

This is the place to list the event or events responsible for the highest level you listed in column two. This final column serves an important explanatory purpose. Say, for example, that you recorded your average stress level as 2 on Monday, but it rose to 5 on Tuesday. If you experienced a sudden rush of orders at work Tuesday, or left work to find your car broken into, the increase is understandable. Unless you note the reasons on the form, however, you may not remember later what caused your stress.

The Daily Stress Record has an important purpose. It helps you to gauge your feelings more realistically. When it comes to stress, your mind can play tricks on you. For example, how oft en have you said on Friday, “Boy, this was a terrible week”? Looking back at your stress records, however, you may discover that in reality only one day went badly. In this way, record keeping can contribute to your peace of mind. Here are sample Daily Stress Records, taken from each of our case studies:

Daily Stress Record—Anne

Daily Stress Record—Erik

Daily Stress Record—Rhani

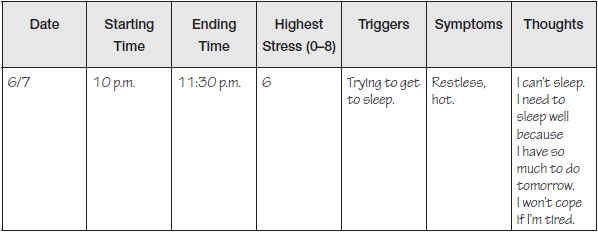

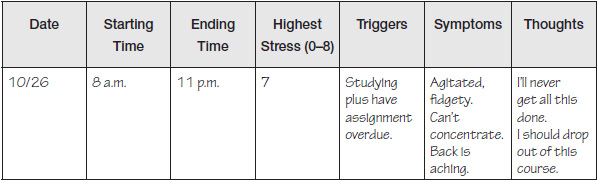

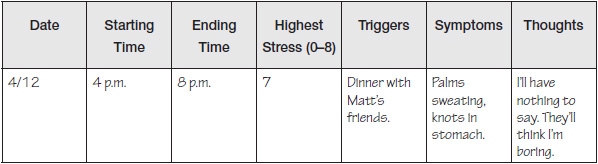

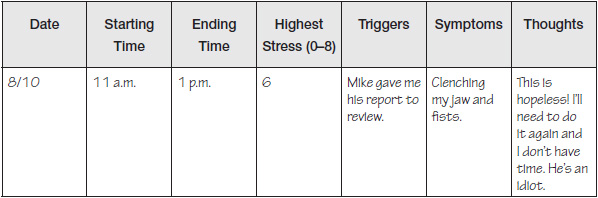

Although you can leave the Daily Stress Record at home and fill it out at night, you should carry the Stressful Events Record with you, so that you can fill it out whenever you notice yourself feeling stressed. That may sound like a burden, but do not worry. You will need to use this form for only a few weeks. Its purpose is to show you more about how you react to certain events. In our experience, many of the clients that we see have a limited understanding of their own responses— they don’t know exactly how they respond to stress. The Stressful Events Record will help you understand your own responses better.

Use the Stressful Events Record every time your stress level rises. Some days you may record many episodes of stress, while other days you may record none. You will find a blank form on page 17 that you may photocopy. Alternatively, you can download it from our web-site: www.oup.com/us/ttw. The following instructions will help you complete the Stressful Events Record.

• Note the approximate time that your stress began to increase.

• Note the approximate time that the level returned to normal.

• Use the 0–8 scale to note the highest level of stress you felt during this particular episode.

• If you know what triggered the stress, note the event or events. This column is likely to echo the “major stressful events” column on your Daily Stress Record for that day.

• Record the major physical symptoms you experienced as a result of this stress—headaches, nausea, pounding heart, or other symptoms.

• Finally, write down the thoughts that went through your head as your stress was increasing. For example, you may have thought, “I won’t make it, I can’t cope” or “I’m going to look foolish.” No matter how silly the thoughts seem after the moment has passed, write them down.

Filling out the Stressful Events Record will help you identify your own particular stress triggers and responses. After a time, you may notice a pattern to your stress, which could point to a specific problem for you to address. Sample Stressful Events Records from our case studies are shown here.

Stressful Events Record—Anne

Stressful Events Record—Erik

Stressful Events Record—Rhani

As you follow this stress management program, you will want to keep track of your progress. Over the weeks, you should notice a gradual drop in your level of stress. Again, however, your mind can play tricks on you. Because you may not remember how you felt before the program, you may not recognize your progress. This is where record keeping comes in. On page 18, you will find a Progress Chart. Copy it, put it in a prominent place, and fill it out every week. The information you record on the Progress Chart will come from your Daily Stress Record.

Here is what to do at the end of each week:

• Calculate your average stress level for the week. You can do this by adding up the “average stress” numbers for each day, then dividing by seven. (If you missed a day in keeping your Daily Stress Record, divide by six—but try not to miss a day!)

• Calculate your average highest stress level. Do this the same way, by adding up the numbers from the “highest stress” column on each Daily Stress Record, then dividing by seven.

• Record these two averages on the chart. The numbers in the vertical column from 0 to 8 represent the stress scale. The numbers in the horizontal row from 1 to 15 represent weeks.

After the first week, you will have two results to record on the chart above the number 1. Work out your own system for doing this. For example, you might use a circle to represent your average stress level and an “x” for your highest stress level. Whatever symbols you choose, place them in the appropriate place on the scale. A sample Progress Chart is shown here.

![]() Read this chapter a few times and commit to memory the essential information.

Read this chapter a few times and commit to memory the essential information.

![]() Complete your Daily Stress Record at the end of your day, every day, for two weeks before beginning Lesson 3. (You can move on to Step 2 next week but keep recording.)

Complete your Daily Stress Record at the end of your day, every day, for two weeks before beginning Lesson 3. (You can move on to Step 2 next week but keep recording.)

![]() Complete your Stressful Events Record during your day, every day, and record each event for two weeks before beginning Step 3.

Complete your Stressful Events Record during your day, every day, and record each event for two weeks before beginning Step 3.

![]() Complete your Progress Chart at a convenient time at the end of the week for the next two weeks before beginning Step 3.

Complete your Progress Chart at a convenient time at the end of the week for the next two weeks before beginning Step 3.

The Daily Stress Record and the Progress Chart will continue to be a part of your exercises every week throughout the program, so you may want to make multiple copies of them.

In this lesson we reviewed the role of stress in our everyday lives.

• Stress is a natural, protective response to threats and challenges.

• Different environments can be more or less stress producing.

• Individuals react and respond differently to similar situations.

• These differences may be explained by genetics, and environmental and learned responses.

• The ultimate level of stress you experience will depend on a combination of the event that is producing the stress and your characteristic way of coping with that event.

• We have three basic stress response systems that interact with each other:

• The physical system

• The mental system

• The behavioral system

• We also introduced you to three key records, which will help you understand your own stress:

• The Daily Stress Record

• The Stressful Events Record

• The Progress Chart