Welcome back. After a week or more of practicing realistic thinking, you should feel yourself making progress. You may still overestimate the probability that bad things will happen, but chances are that your estimates are becoming more realistic every day. While you keep working on that skill, it’s time to tackle the other misunderstanding in thinking that is common to people under stress: overestimating the consequences of a negative event. You might think of it as making mountains out of molehills.

To highly stressed people, life seems to pack a double whammy. They believe that unpleasant events are likely to happen, and they believe that if those events happen, the consequences will be absolutely horrible. People who “catastrophize” automatically expect the worst possible outcome. For example, if these individuals are awakened by a noise in their house at night, they may immediately assume that it is a burglar who is going to harm or kill them. If they are called into the boss’s office, they immediately think they are going to be fired.

Most people who assume the worst are unaware they are doing it. Since they have never stopped to identify the consequences they are imagining, the consequences stay at a subconscious level, where they cannot be disproved. In other words, the unrealistic consequences are like the unrealistic probabilities we discussed in Step 3. They lurk in the darkness of your mind, ready to do harm, until you bring them out and see them for what they are.

You can identify the consequences you assume by asking yourself a simple question: “What would happen if the thing I am worried about really took place?” As we said before, realistic thinking is not purely positive thinking. We have to admit the possibility that negative things can happen. The last lesson showed you that the chance of these negative things happening is often far less than you might have thought, but still there is a chance. So the next step is to accept that chance and then ask yourself: “If the negative thing I expect did occur, what would really happen?” The answer to this question will produce the expected consequence of your first belief. As you will see, this expected consequence will simply be another negative expectation. Therefore, you are now in a position to examine the realistic evidence for this second belief. In most cases, you will find that the consequences would not be nearly as bad as you first assumed. The same rules apply to the consequence as to the initial expectation—try to phrase it as a statement and try to stay away from feelings or voluntary actions.

Let’s return to the example in which your partner is late getting home and your first thought is that he or she has had an accident. When you think realistically, you may realize that the chance of this is very small—less than 1 percent. But that’s still a chance. So, your next step is to ask yourself, “What would really happen if my partner did have an accident?”

At this point you will be doing something that may or may not come naturally, talking to yourself. You do not have to do it aloud—although there is nothing wrong with that if it makes you feel more comfortable. All you have to do is ask yourself questions and then answer them. Although talking to oneself has a bad reputation, it is actually very useful. You should get into the habit of mentally asking and answering questions as you practice realistic thinking.

When you ask yourself what would really happen if your partner had an accident, you might immediately answer, “He or she would be killed.” What does this answer remind you of? Right—it is an overestimation of probability, and you know what to do with those! It is obvious that most accidents are not serious enough that they kill or maim people. It should now be obvious that overestimations of consequences are simply overestimations of probability that lie below your original thoughts—sort of like the layers of an onion.

Asking yourself, “What would really happen if. . .?” or “So what if. . .?” is just another way of identifying your next thought. Many people find that asking these questions opens a sort of Pandora’s box, with one thought leading to another and another. It is important to keep going and identify all your thoughts, no matter how frightening or silly they seem, until you reach the bottom of the box.

If you think realistically, you would eventually learn to cope even if your partner were hurt or killed in an accident. This may sound callous, but it is a realistic fact. Humans can cope with an amazing amount of difficulty. When you reach the answer that is at the bottom of all the questions you are asking yourself, you will usually find that it is not the end of the world, as you feared.

The following examples show the kind of questioning we have been discussing. Our first case, about Rhani, is a good illustration of how one question can lead to another and another until the bottom line is reached. In these examples, the questions are asked by experts, but you can do the same kind of questioning yourself.

Rhani had a customer who seemed unhappy with the beauty treatment that Rhani provided.

RHANI: I’m worried that she will call or write to my boss to complain.

PROFESSIONAL: How likely is it that she will do that?

RHANI: I know it’s not very likely. If she was going to complain, she probably would have done it at the time of the treatment. If she wasn’t happy she’ll probably just take her business elsewhere. The likelihood of her bothering to call or write is probably only 5 percent.

Note: Rhani has been doing Step 3 for a week or two and is clearly able to look at evidence for her initial belief quite quickly.

PROFESSIONAL: Let’s assume she does call to complain. What would happen?

RHANI: My boss would fire me.

PROFESSIONAL: It sounds like you are assuming there’s a 100 percent probability that your boss would fire you. How likely do think that really is? Try and look at some evidence.

RHANI: Hmmm. . . . I’m generally a good beautician. I know of other customers who have complained and the people who did their treatments didn’t get fired. It wasn’t as though I did anything wrong—I think the customer just had unrealistic expectations about the results of the treatment. I can explain that to my boss . . . if she’ll listen. So, when I look at all the evidence, I guess it’s not that likely that I would get fired—maybe 10 percent.

Note: See how the professional treated Rhani’s first consequence to her initial thought as simply another overestimation of probability and asked Rhani to examine the evidence for it, which Rhani is now very good at doing.

PROFESSIONAL: Okay. But let’s not stop there. What would happen if you did get fired?

RHANI: That would be awful.

PROFESSIONAL: Why? What would really happen?

RHANI: Well, I’d be out of work. Who knows if I’ll ever find another job.

PROFESSIONAL: I’ve noticed that you just made a prediction there. You essentially said, “I’ll never find another job.” Could you take some time to think through the evidence for that?

RHANI: Well, I’m not sure. It didn’t take me too long to find this job, I suppose. So it might not take that long to find another one. But the job market is not as good as it used to be. That said, I do have a couple of friends from beauty college who found work recently. So, I don’t really know the probability of not finding another job, but it’s definitely not 100 percent like I first thought.

PROFESSIONAL: And what would happen if you didn’t find another job?

RHANI: I guess I’d have to move back in with my parents until I found something. I wouldn’t like that, but I guess it wouldn’t be the end of the world. I could use the opportunity to do some extra study so I could get a better job next time.

PROFESSIONAL: So, in other words, putting all that together, there seems to be only a small chance that the customer will complain to your boss. And even if they do, there’s only a small chance that you would get fired. And even if you did, you may well find another job quickly, and even if you didn’t, you would survive. So it doesn’t sound as bad as it first seemed. How much stress do you feel now?

RHANI: Not much at all. When you put it that way, it isn’t nearly so stressful.

Erik had an assignment due the next day and was worried that he would not get it done on time.

ERIK: I’m so disappointed in myself. I really wanted to get everything in on time this semester, but I can’t get this done by tomorrow.

PROFESSIONAL: How much have you done?

ERIK: I have done lots of research and have written a draft. But it needs to be completely rewritten.

PROFESSIONAL: What would happen if you handed it in as it is?

ERIK: I’d get a bad mark.

PROFESSIONAL: Have you ever gotten a bad mark before?

ERIK: Well, I’ve failed a few times, but that’s only been when I haven’t handed the assignment in at all. Whenever I have actually managed to submit the assignment, I have gotten a really good mark.

PROFESSIONAL: Have you ever submitted an assignment you didn’t feel happy with?

ERIK: Lots of times. I’m basically never happy with what I submit. I always think it could be better.

PROFESSIONAL: What feedback have you had from your teachers about your work?

ERIK: They say it’s excellent. But they also say I need to be more consistent with handing things in on time.

Note: Here the professional has been asking Erik to look at different types of evidence—particularly, his past experience and the general knowledge he has about his marks.

PROFESSIONAL: So then, looking at all the evidence, how likely do you think it is that you would get a really bad mark, like a fail mark, if you were to hand in the assignment tomorrow?

ERIK: Oh, I guess about 10 percent. But I’d feel terrible. I hate knowing that I could have done better.

PROFESSIONAL: Okay. Now let’s assume that you do feel terrible after handing it in. What would happen?

ERIK: What do you mean? I’d feel terrible—that’s bad enough!

PROFESSIONAL: You mentioned earlier that you are usually unhappy with work you submit because you think it could be better. In your experience, how long does that terrible feeling last?

ERIK: Well, actually, it is usually only really terrible for a few minutes. Then I get distracted by the next thing I need to do and I forget about it until I get the assignment back.

PROFESSIONAL: And how do you feel when you don’t hand something in on time?

ERIK: I feel really guilty and disappointed in myself. And that feeling actually drags on for a lot longer.

PROFESSIONAL: So again, how bad would it be if you felt terrible after handing something in?

ERIK: It wouldn’t be so bad—I know the feeling only lasts a few minutes, and it is a lot better than if I don’t hand anything in at all. Plus, I’d be a step closer to finishing my degree.

Joe’s mother calls him frequently, often interrupting him while he is busy with work or other tasks.

JOE: My mother is always calling just when I’m in the middle of doing something important, and it makes me so angry, I find that I get short with her.

PROFESSIONAL: Let’s try and look at what you just said in a more realistic way. When you say that she always calls in the middle of something, it implies 100 percent of the time. Is that true? How likely is it really that she will call when you are doing something important?

JOE: Well, I suppose that when I think back over the last 10 times she’s called, most of the times I was just watching TV or reading. There was once when I was making dinner and it burned because she interrupted me. Another time, I was busy with some work I had brought home from the office and she called. I guess that makes it 20 percent of the time.

PROFESSIONAL: OK, great. That’s the first part. Now let’s go a bit further. Ask yourself, “So what if she calls at an inconvenient time?”

JOE: Well, I know that one of my first thoughts is that she doesn’t think anything I do is important. But, before you say anything, I know that is a major overestimation since she obviously doesn’t know what I’m doing when she calls. However, I suppose I also think that it’s a major interruption and inconvenience to have to stop at that point.

PROFESSIONAL: A major inconvenience sounds pretty extreme. What is the evidence that it is so major?

JOE: When I was doing my work, I forgot what I was up to and it took me 10 minutes to work it out again. I guess that’s not so bad—it’s only 10 minutes. And when the dinner burned, it was really not too bad, just a little burned. Part of that was my fault anyway, because I could have turned the stove down before I went to the phone.

PROFESSIONAL: So, it sounds like, even when she does interrupt, it is an inconvenience, but maybe not such a major one.

JOE: True. And I know what you are going to say next. Even if it is a major inconvenience, it’s not the end of the world. I have handled plenty of bigger problems than this at work.

In questioning Erik, Rhani, and Joe, the professional was challenging them—challenging the probability that negative events would happen and challenging the likelihood of the dire consequences they imagined. Below are some additional tips for thinking realistically, so that you can learn to challenge your own thinking, just as a professional might.

Learning to think realistically means learning to see things objectively. One way to move toward this goal is to try looking at your situation from someone else’s point of view. We have already discussed this technique as one way of gathering evidence to determine realistic probabilities. But the technique can be used in a broader way, and it is so useful that it is worth describing in more detail.

Think about the people you know. Is there a person whose calm, logical manner you have always admired? Someone who never seems to lose his or her cool, no matter what happens? You have a choice. You can let people like that drive you crazy or you can get pointers from them. Choose the calmest person you know and try to find out how his or her mind works. Because everyone likes compliments, you may want to start by saying something like, “You know, I’ve always admired the way you stay calm in upsetting situations. How do you do it?” Chances are, the person will be glad to talk. Or perhaps you already know the person well enough to know the attitudes that keep him or her on an even keel.

Let’s say that the calmest person you know is Lee. After you have talked to Lee, experiment with seeing the world from Lee’s perspective. The next time a stressful event happens, ask yourself, “What would Lee think about this?” Or try imagining that the event has happened to Lee instead of you. What would you think about that event if you knew that it had happened to Lee? If Lee came to you asking for advice, what would you say? It’s possible that you would give very good, useful advice to other people but have trouble knowing what to do when you are in a similar situation yourself. Putting yourself in someone else’s shoes works especially well in three areas that worry people under stress: social concerns, perfectionism, and anger.

Social concerns is a name for something that everyone does: worry about what other people think of you. For some people, this kind of worry can become so intense that they become afraid to do anything. If you tend to worry too much about other people’s opinions of you, try pretending to be those other people. Let’s say, for example, that you bump into a coworker in the supermarket and introduce your spouse—but you call your coworker by the wrong name. Immediately, you feel embarrassed. Because you have practiced realistic thinking, you know that your embarrassment comes from a thought, probably something like, “That person must think I’m totally stupid.” Now turn the situation around and imagine that your coworker had introduced you by the wrong name. Would you have thought he or she was completely stupid? Probably not. And even if you did feel bad about it for a minute, you probably would have laughed about it the next time you saw your coworker, right? So by reversing positions, you have come up with easy evidence to help lower the probability of the statement, “That person must think I’m stupid.”

The desire to do things perfectly causes as much stress in many people as worrying about what others think. Logically, we all know that no one is perfect. Unconsciously though, we oft en believe that we should be. Again, putting yourself in someone else’s shoes is a good way to gather evidence against such thoughts.

For example, if your boss asks you to do a special project, you may immediately begin to worry that your performance will not be good enough. The worry probably results from an unconscious thought such as, “It will be a disaster if I make even one mistake.” But what if one of your colleagues at work did the same project and made a few small errors? Would that really be terrible? Would you think that your colleague was a hopeless case and should be fired? Of course not. You would probably think, “It’s too bad about those mistakes, but everyone makes them, and overall that person did a good job.” Once again, reversing positions has shown you that the probability of your original thought—that any mistake would be disastrous—was really very low.

Many people under stress have a tendency to become angry and irritable for often totally irrational reasons. In many cases, they may hold unconscious beliefs that others are stupid or nasty, and that they themselves are battling everyone else’s incompetence. In such cases, putting yourself in another person’s position is a good way of gaining perspective and being able to understand and forgive minor mistakes in others. For example, let’s assume you are driving to a meeting and you are a little late. Suddenly, in front of you, a car changes lanes and then proceeds to drive quite slowly. Your immediate response may be to get angry and to start sounding your horn. These responses are probably being produced by thoughts along the lines of: “That jerk!”; “He’s totally inconsiderate!”; “He’s purposefully trying to make me late!”; and so on. Now try to put yourself in the front car’s position. Have you ever driven anywhere slowly, perhaps because you were looking for something or your mind was preoccupied? Do you always carefully watch all of the other cars when you are in a hurry? By gaining this perspective, you may then be in a better position to do your other realistic thinking and realize that by driving behind this car you are only going to arrive at your meeting a few seconds later than you would have anyway.

You have already been challenging your probability estimates, using the Realistic Thinking Record. We now want to introduce you to a new Realistic Thinking Record, shown on page 00.

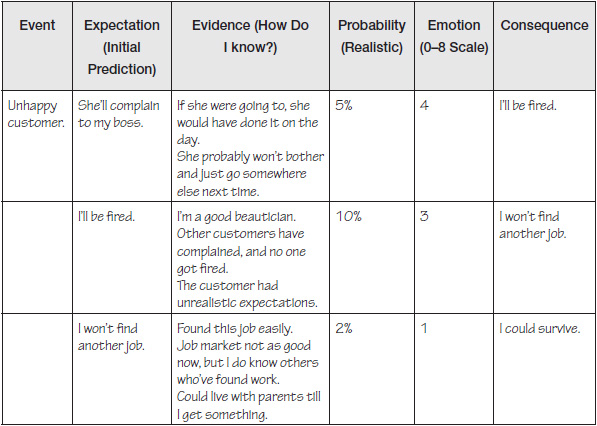

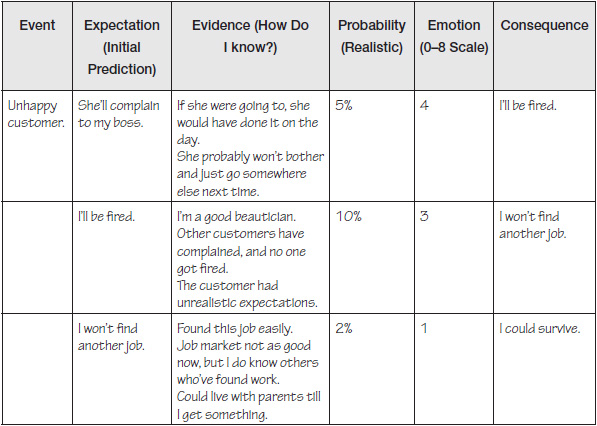

Rhani’s Realistic Thinking Record

The first five columns of this new form are just like the old one. You will record the objective event, your initial expectation about it, the realistic evidence for your expectation, the realistic probability that what you expect will actually occur, and your emotional intensity. Then, to complete the final column, ask yourself, “What would happen if the negative thing I expected actually did occur?” or “So what if my initial belief is true?” As we discussed earlier, this will help to identify your expected consequence. Write that consequence in the last column. But wait! You’re not done yet!

Below the place where you wrote your initial thought, write the consequence again. This is important because you now need to look at the evidence for your expected consequence. Now start the whole process over as if that were your initial thought. In other words, challenge this consequence just the way you challenged your initial thought. After you have looked at all of the evidence and come up with a realistic probability for this second level, ask yourself, “What would happen if this new possibility (my previous consequence) really occurred?” In answer to this, you might come up with another consequence. Record it in the consequence column (below the first), then start a separate line and again write that consequence back in the initial expectation column (now your third expectation). You then need to challenge that consequence as an initial thought—that is, look at evidence and so on. Keep on going until you can’t go any further. This usually happens when you can’t think of any other consequences, or you reach zero emotion. At the end, you should read back over the whole exercise and realize just how unlikely it is that anything really bad will happen. Remember that the likelihood of each consequence depends on the likelihood of the belief before it. For example, if you decide there is a 1 percent chance that you will lose your job after making a mistake and then decide that if you lose your job, there is a 10 percent chance that you will not get another one, the overall chance that you will be out of work is 0.1 percent—that is, 10 percent of 1 percent—or, almost none!

The process will become clearer if you study the sample below that reflects Rhani’s case discussed earlier in the lesson. As you can see, a single event has the potential to produce a page or more of thoughts. Make several copies of the Realistic Thinking Record, and do not be afraid to use as many as you need. Eventually you will not need the sheets at all; you will be able to do all of your challenging in your head. But as with all the other skills you are learning, this one takes practice.

![]() Use the new Realistic Thinking Record on page 52 for at least the next three weeks to practice challenging your probabilities and your consequences.

Use the new Realistic Thinking Record on page 52 for at least the next three weeks to practice challenging your probabilities and your consequences.

![]() Remember:

Remember:

![]() Follow your chain of thoughts as far as you can, no matter how silly some of your thoughts seem.

Follow your chain of thoughts as far as you can, no matter how silly some of your thoughts seem.

![]() Fill out the sheet during or as close to the stressful event as possible.

Fill out the sheet during or as close to the stressful event as possible.

![]() Carry a few sheets with you, and get into the habit of turning to them. Soon it will become second nature.

Carry a few sheets with you, and get into the habit of turning to them. Soon it will become second nature.

![]() Continue to fill in your

Continue to fill in your

![]() Relaxation Practice Record

Relaxation Practice Record

![]() Daily Stress Record

Daily Stress Record

![]() Progress Chart

Progress Chart

In this lesson we continued our exploration of realistic thinking.

• We emphasized the importance of continuing your thought process beyond your “initial expectation” and looking at your expected consequence.

• This expected consequence can then be seen as a new belief that can also be challenged by looking at all of the evidence.

• Some events or situations will result in many layers of beliefs.

• We presented case examples to illustrate how this process takes place.