From its striped marble Cathedral to its tunnelled alleys, brilliant Campo and black-and-white city emblem, Siena is a chiaroscuro city. In its surging towers it is truly Gothic. Where Florence is boldly horizontal, Siena is soaringly vertical; where Florence has large squares and masculine statues, Siena has hidden gardens and romantic wells. Florentine art is perspective and innovation, while Sienese art is sensitivity and conservatism. Siena is often considered the feminine foil to Florentine masculinity.

For such a feminine and beautiful city, Siena has a decidedly warlike reputation, nourished by sieges, city-state rivalry and Palio battles. The pale theatricality in Sienese painting is not representative of the city or its inhabitants: the average Sienese is no ethereal Botticelli nymph, but dark, stocky and swarthy.

A brief history

In keeping with Sienese mystique, the city’s origins are shrouded in myths of wolves and martyred saints. According to legend, the city was founded by Senius, son of Remus, hence the she-wolf symbols you will encounter throughout the city. St Ansano brought Christianity to Roman Siena and, although he was promptly tossed into a vat of hot tar and beheaded, he has left a legacy of mysticism traced through St Catherine and St Bernardino to the present-day cult of the Madonna. The power of the Church came to an end when the populace rose up against the Ecclesiastical Council and established an independent republic in 1147. The 12th century was marked by rivalry in which the Florentine Guelfs usually triumphed over the Sienese Ghibellines.

A Sienese backstreet café.

Steve McDonald/APA

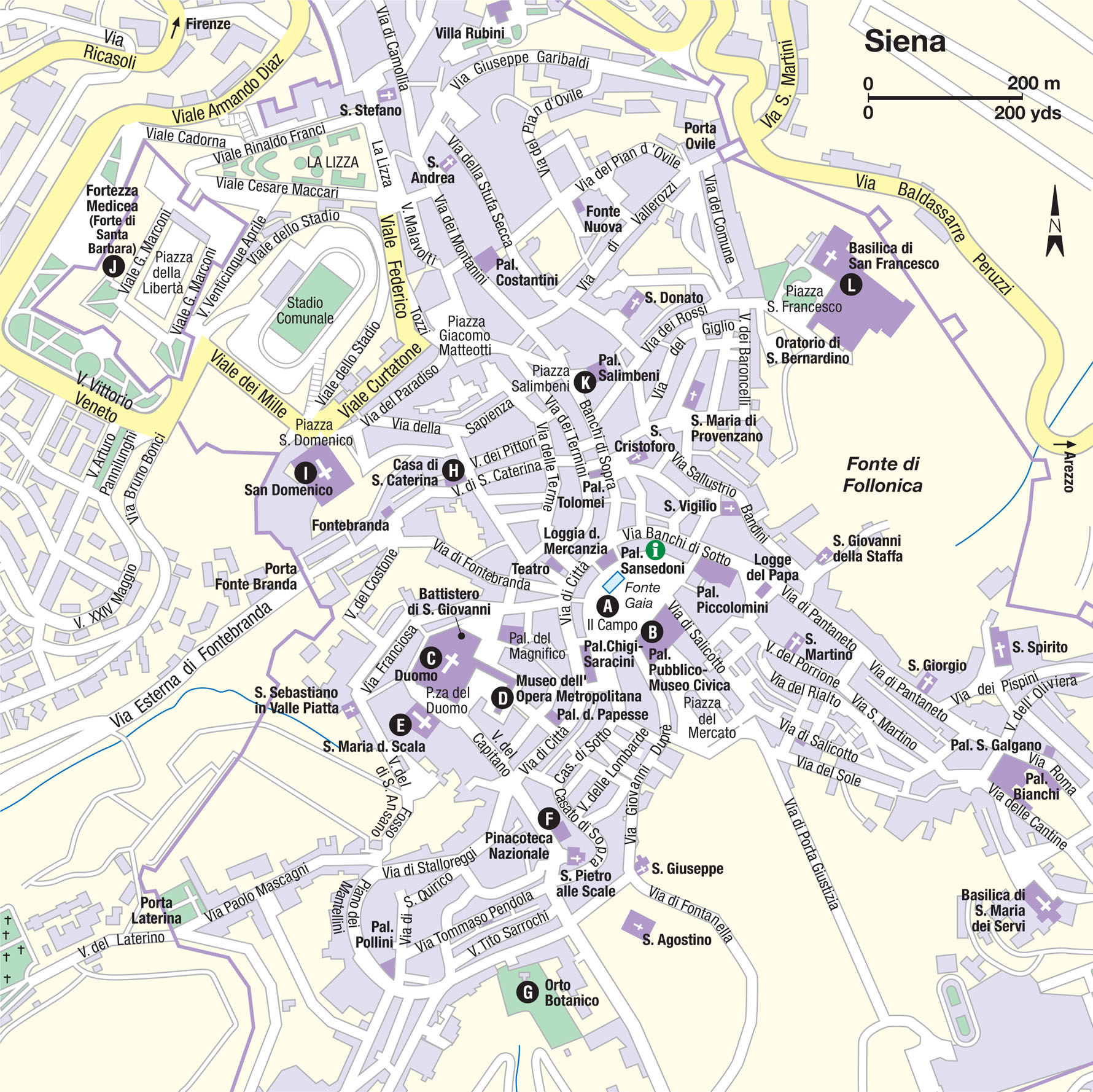

The city is divided into three districts or terzi (thirds) – The Terzo di San Martino, Terzo di Città and Terzo di Camollia. But this is purely an administrative division; Siena’s true identity is inextricably linked to the contrade, the 17 medieval districts from which its social fabric is woven.

In 1260, the battle of Montaperti routed the Florentines and won the Sienese 10 years of cultural supremacy, which saw the foundation of the University and the charitable “fraternities”. The Council of the Twenty-Four – a form of power-sharing between nobles and the working class – was followed by the Council of Nine, an oligarchy of merchants that ruled until 1335. Modern historians judge the Nine self-seeking and profligate, but under their rule the finest works of art were either commissioned or completed, including the famous amphitheatre-shaped Campo, the Palazzo Pubblico and Duccio’s Maestà.

The ancient republic survived until 1529, when the reconciliation between the pope and the emperor ended the Guelf-Ghibelline feud. The occupying Spanish demolished the city towers, symbols of freedom and fratricide, and used the masonry to build the present fortress. The final blow to the republic was the long siege of Siena by Emperor Charles V and Cosimo I in 1554.

After the Sienese defeat, the city of Siena became absorbed into the Tuscan dukedom. As an untrusted member of the Tuscan Empire, impoverished Siena turned in on itself until the 20th century. Still today, Siena’s tumultuous history as arch-rivals of Florence is written in the streets and squares, and resonates in the passionate souls of the Sienese. Of all Tuscans, the Sienese have the longest memories and there are local aristocrats who still disdain to visit Florence.

Change is anathema to the city: traditional landowning, financial speculation, trade and tourism are more appealing than the introduction of new technology or industry. Siena has made a virtue of conservatism; stringent medieval building regulations protect the fabric of the city; tourism is decidedly low-key; old family firms such as Nannini, Siena’s most famous café, do a roaring trade with locals (and also produced Gianna Nannini, one of Italy’s best-known female singers). Siena is Italy’s last surviving city-state, a city with the psychology of a village and the grandeur of a nation.

Romulus, Remus and the she-wolf: Remus’ son is said to have founded Siena.

Steve McDonald/APA

Il Campo

All roads lead to Il Campo A [map] , the huge main central square, shaped like an amphitheatre – the Sienese say that it is shaped like the protecting cloak of the Virgin, who, with St Catherine of Siena, is the city’s patron saint. From the comfort of a pavement café on the curved side of the Campo, you can note the division of the paved surface into nine segments, commemorating the beneficent rule of the “Noveschi” – the Council of Nine that governed Siena from the mid-13th century to the early 14th, a period of stability and prosperity when most of the city’s main public monuments were built.

Chiocciola contrada; traditionally, its residents worked as terracotta makers.

Steve McDonald/APA

The Campo is tipped with the Renaissance Fonte Gaia (Fountain of Joy). The marble carvings are copies of the original sculptures by Iacopo della Quercia, which are on display in Santa Maria della Scala (click here). Beneath the fountain lies one of Siena’s best-kept secrets – a labyrinth of medieval tunnels extending for 25km (15½ miles), constructed to channel water from the surrounding hills into the city. The undergound aqueduct has two main tunnels: one leads to the Fonte Gaia and the other to the Fonte Branda, the best preserved of Siena’s many fountains. Parts of this subterranean system can be visited and explored on a guided tour (enquire at the tourist office for more information).

“Contrade” Passions

Siena’s cultural aloofness owes much to the contrade, the 17 city wards designated for now-defunct administrative and military functions during the Middle Ages, which continue to act as individual entities within the city. To outsiders, the only real significance of the contrade seems to be in connection with the Palio (click here), but their existence pervades all aspects of daily life. Despite its public grandeur, parts of Siena are resolutely working class and attach great weight to belonging to a community. Events such as baptisms are celebrated together, while traditional Sienese will only marry within their contrada.

All over the city, the importance of the various contrade is evident. Little plaques set into the wall indicate which contrada you are in (such as snail unicorn, owl, caterpillar, wolf or goose). Each neighbourhood has its own fountain and font, as well as a motto, symbol and colours. The last are combined in a flag, worn with pride and seen draped around buildings for important contrada events, notably a Palio triumph. To gain an understanding of this secret world, book a private Palio tour (tel: 057-7280 551) that takes you to the individual museums, churches and stables associated with individual contrade, all in the heart of the city.

At the square’s base is the Palazzo Pubblico B [map] , the dignified Town Hall with its crenellated facade and waving banners, surmounted by the tall and slender tower. The Town Hall, which has been the home of the commune since it was completed in 1310, is a Gothic masterpiece of rose-coloured brick and silver-grey travertine. Each ogival arch is crowned by the balzana, Siena’s black-and-white emblem representing the mystery and purity of the Madonna’s life.

The distinctive Torre del Mangia (daily 10am–7pm, until 4pm Nov–mid-Mar; charge) – named after the first bell-ringer, Mangiaguadagni, the “spendthrift” – is 87 metres (285ft) high, and it’s a 500-step climb to the top to enjoy glorious views of the pink piazza and Siena’s rooftops. At the bottom of the tower, the Cappella in Piazza (Chapel in the Square) was erected in 1378 in thanksgiving for the end of the plague.

The city museum

Although bureaucrats still toil in parts of the Palazzo Pubblico, as they have for some seven centuries, much of the complex is now dedicated to the Museo Civico (daily Mar–Oct 10am–7pm, until 5.30pm or 6pm Nov–mid-Mar; charge), which displays some of the city’s greatest treasures.

Siena’s city council once met in the vast Sala del Mappamondo, although the huge map that then graced the walls has disappeared. What remains are two frescoes attributed to the medieval master Simone Martini: the majestic mounted figure of Guidoriccio da Fogliano and the Maestà. Martini’s Maestà, a poetic evocation of the Madonna seated on a filigree throne, has a rich, tapestry-like quality. The muted blues, reds and ivory add a gauzy softness. Martini echoes Giotto’s conception of perspective, yet clothes his Madonna in diaphanous robes, enhancing her spirituality in dazzling decoration.

Opposite is the iconic Guidoriccio, the haughty diamond-spangled condottiero (mercenary) reproduced on calendars and panforte boxes. But in recent years, despite Sienese denials, doubts have been cast on the authenticity of the fresco. Art historians maintain that a smaller painting uncovered below the huge panel is Martini’s original, and the Guidoriccio we see was executed long after the artist’s death.

In the next room is a genuine civic masterpiece, Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Effects of Good and Bad Government, painted in 1338 as an idealised tribute to the Council of the Nine. Its narrative realism and the vivid facial expressions used on this impressive painting give the allegory emotional resonance to observers. A wise old man symbolises the common good, while a patchwork of neat fields, tame boar and busy hoers suggests order and prosperity. By contrast, Bad Government is a desolate place, razed to the ground by a diabolical tyrant, the Sienese she-wolf at his feet.

Turf Wars

The Palio horse race is the symbol of the Sienese’s attachment to their city, and outsiders challenge it at their peril. One of the piazza’s tight turns, the Curva di San Martino, set at a 95-degree angle, has often been the cause of fatalities among horses. Animal-rights activists have long protested against the event and Michele Brambilla, the Minister for Tourism, recently refused to allow the race to be put forward for Unesco World Heritage status. She said: “The shame of 48 horse deaths since 1970 marks the Palio of Siena, and a current investigation will shed light on accusations of doping in some horses. This damages the image of one of the most beautiful cities in the world.” The Sienese beg to differ.

TIP

The Duomo’s museum allows access to the parapets, which offer dazzling views of Siena – a more accessible alternative to the Torre del Mangia’s panorama.

Exiting the Campo, turn left and head up the hill via one of the winding streets to the Piazza del Duomo. The Duomo C [map] (www.operaduomo.siena.it; Mon–Sat 10.30am–7.30pm, Sun 1.30–6pm; combined ticket) is Siena’s most controversial monument, either a symphony in black-and-white marble, or a tasteless iced cake, depending on your point of view. It began in 1220 as a round-arched Romanesque church, but soon acquired a Gothic façade festooned with pinnacles. Bands of black, white and green Tuscan marble were inlaid with pink stone and topped by Giovanni Pisano’s naturalistic statues.

Siena’s ornate cathedral.

Steve McDonald/APA

TIP

Siena is not the cheapest place to shop, but it is full of enticing shops, galleries and boutiques selling quality goods, often handmade. The main shopping streets are Via Banchi di Sopra and Via di Città. Opening hours are generally 9.30am–1pm and 3–7pm. Many shops close on Mondays.

The Cathedral interior is creativity run riot – oriental abstraction, Byzantine formality, Gothic flight and Romanesque austerity. A giddy chiaroscuro effect is created by the black-and-white walls reaching up to the starry blue vaults.

The inlaid floor is even more inspiring, and the Duomo is at its best between August and October when the intricate marble-inlaid paving is on display. Outside these times, to preserve the well-restored floor, many of the most captivating scenes are hidden. Major Sienese craftsmen worked on the marble pavimentazione between 1372 and 1562. The finest scenes are Matteo di Giovanni’s pensive sibyls and the marble mosaics by Beccafumi. Giorgio Vasari called these “the most beautiful pavements ever made”.

Nicola Pisano’s octagonal marble pulpit is a Gothic masterpiece: built in 1226, it is a dramatic and fluid progression from his solemn pulpit in Pisa Cathedral. Off the north aisle is the decorative Libreria Piccolomini (Mon–Sat 9am–7.30pm, Sun 1–7.30pm), built in 1495 to house the personal papers and books of Pope Pius II. The frescoes by Pinturicchio (1509) show scenes from the life of the influential Renaissance pope, a member of the noble Sienese Piccolomini family and founder of the town of Pienza.

The fan-shaped Campo.

iStockphoto.com

The Crypt is an extraordinary discovery, with recently revealed frescoes attributed to Duccio’s school. Because the frescoes were perfectly concealed for so long, the intensity of the colours shines through in a vivid array of blue, gold and red. Given that the frescoes date from 1280, the “modern” expressiveness is all the more remarkable.

In the unfinished eastern section of the Cathedral is the Museo dell’ Opera Metropolitana D [map] (daily Mar–May and Sept–Oct 9.30am–7pm, June–Aug until 8pm, Nov–Feb 10am–5pm; combined ticket with Duomo) and Pisano’s original statues for the facade. In a dramatically lit room above is Duccio’s Maestà, the Virgin Enthroned, which graced the High Altar until 1506. Siena’s best-loved work, the largest known medieval panel painting ever, was escorted from the artist’s workshop to the Duomo in a torchlit procession in 1311. The biggest panel depicts the Madonna enthroned among saints and angels, and, since the separation of the painting, facing scenes from the Passion. Although Byzantine Gothic in style, the Maestà is suffused with melancholy charm. The delicate gold and red colouring is matched by Duccio’s grace of line, which influenced Sienese painting for the next two centuries. The Sienese believe that Giotto copied Duccio but sacrificed beauty to naturalism. The small panels do reveal some of Giotto’s truthfulness and sense of perspective.

Around the Cathedral

Opposite the cathedral on the piazza, Santa Maria della Scala E [map] (www.santamariadellascala.com; daily mid-Mar–mid-Oct 10.30am–6.30pm, mid-Oct–mid-Mar 10.30am–4.30pm; charge) is often described as a city within a city. It began as a hospital a thousand years ago and continued as one until its reincarnation as a museum in the year 2000. The far-sighted foundation originally functioned as a pilgrims’ hostel, a poorhouse, an orphanage and a hospital, but is now a magnificent museum complex, embracing frescoed churches, granaries and an archaeological museum. Symbolically, the hospital door never had a key, demonstrating its role as a sanctuary to all-comers. The Pilgrims Hall, depicting care for the sick, is frescoed by Siena’s finest 15th-century artists. The scenes portrayed, of wet-nurses, alms-giving and abandoned children, reveal a human side of the city absent from the luminous sacred art. The complex is also a venue for major medieval and Renaissance art exhibitions.

St Catherine, the daughter of a Sienese dyer, devoted her early life to the needs of the poor and sick. She then turned to politics and dedicated herself to reconciling anti-papal and papal forces; she was instrumental in the return of Pope Gregory XI, exiled in Avignon, to Rome. All the places she visited, from the day of her birth, have been consecrated.

The city’s Museo Archeologico (times as above; combined ticket) is also here, with its significant collection of Etruscan and Roman remains. The vaulted, former granaries make a moody setting for the display of Etruscan treasures, including funerary urns and sarcophagi from Sarteano.

A set of steps behind the Duomo leads down to Piazza San Giovanni, a small square dominated by the Battistero di San Giovanni (times as for the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo and Crypt; combined ticket), built beneath part of the Cathedral. Inside are frescoes and a beautiful baptismal font by Jacopo della Quercia.

Statue of Sallustio Bandini, founder of Siena’s library, on Piazza Salimbeni.

Guglielmo Galvin and George Taylor/APA

Two art museums

There are two art museums in the vicinity of the Cathedral complex, at opposite ends of the scale of their content. The Pinacoteca Nazionale F [map] (Via San Pietro 29; Tue–Sat 8.15am–7.15pm, Sun and Mon until 1pm; charge) contains the finest collection of Sienese “Primitives” in the suitably Gothic Palazzo Buonsignori. The early rooms are full of Madonnas, apple-cheeked, pale, remote or warmly human. Matteo di Giovanni’s stylised Madonnas shift to Lorenzetti’s affectionate Annunciation and Ugolino di Neri’s radiant Madonna. Neroccio di Bartolomeo’s Madonna is as truthful as a Masaccio.

As a variant, the grisly deaths of obscure saints compete with a huge medieval crucifix with a naturalistic spurt of blood. The famous landscapes and surreal Persian city attributed to Lorenzetti were probably painted by Sassetta around a century later. But his Madonna dei Carmelitani is a sweeping cavalcade of vibrant Sienese life.

Sienese pastries are so renowned that they even have their own saint watching over them, San Lorenzo. Exotic spices reached Siena along the Via Francigena pilgrimage route, and many find their way into the medieval recipes still used today. Panforte, a rich, filling cake, dates back to 1205, and is often eaten with sweet Vin Santo. The intense flavours are created by a mix of honey, almonds, hazelnuts, candied orange peel, and a secret blend of spices such as cinnamon and nutmeg. Panpepato, a spicier version, predates it. The delicacy was originally the preserve of Sienese nuns, who guarded their secret recipes, which were also a source of revenue. Such was panforte’s popularity that even in the 14th century, it was being exported. Originally a festive treat, panforte is now eaten all year round. Ricciarelli, small almond biscuits, are also typically Sienese, and far lighter.

The most famous place for panforte is Nannini (Banchi di Sopra 24), a bar and pastry shop, but Pasticceria Bini (Via Stalloreggi 91) is even more illustrious, occupying what was supposedly Duccio’s workshop. Carved into the former stables of a patrician palace, Antica Drogheria Manganelli (Via di Citta 71) is another exotic shop for Sienese delights.

Those suffering from a surfeit of medieval sacred art can visit the Palazzo delle Papesse (Via di Città 126; Tue–Sun noon–7pm; charge), a contemporary art gallery with changing exhibitions, which also offers a 360-degree view of Siena from its loggia.

For some outdoor space and greenery, turn left out of the gallery and head south to the Orto Botanico G [map] (Via P.A. Mattioli 4; Mon–Fri 8am–5.30pm, Sat 8am–noon), a small botanical garden just inside the city walls. Opposite the Orto Tolomei is another little garden, with a lovely view over the countryside and a sculpture that – although not obvious at first glance – outlines the shape of the city.

St Catherine trail

Slightly outside the historic centre, on Vicolo del Tiratoio, is the Casa di Santa Caterina da Siena H [map] (Costa di Sant’ Antonio; daily 9am–12.30pm, 3–6pm; free), the home of Catherine Benincase (1347–80), canonised in the 15th century by Pope Pius II and proclaimed Italy’s patron saint in 1939, along with St Francis of Assisi. The house, garden and her father’s dye-works now form the “Sanctuary of St Catherine”. Although never taking holy orders, Catherine was an ascetic, and lived like a hermit in a cell, reputedly sleeping with a stone as her pillow. If it didn’t sound too smug, the Sienese would admit to spiritual superiority. Apart from producing two saints and fine religious art, the city still venerates the Virgin.

Shopping for sweet treats in a deli.

Britta Jaschinski/APA

Inside the nearby Basilica di San Domenico I [map] (Apr–Oct 7am–6.30pm, Nov–Mar 9am–6pm; free) – a huge fortress-like church founded by the Dominicans – a reliquary containing the saint’s head is kept in the Cappella Santa Caterina. The chapel is decorated with frescoes depicting events in the saint’s life, the majority completed by Il Sodoma in the early 16th century. The view from outside the Basilica across to the Duomo is spectacular.

The Fortress

From here it’s a short walk to the Forte di Santa Barbara, also known as the Fortezza Medicea J [map] , built by Cosimo I after his defeat of Siena in 1560. The red-brick fortress now houses an open-air theatre, provides glorious views of the countryside and contains the Enoteca Italiana (tel: 0577-288 811; Mon–Sat noon–1am). The latter, a wine exhibition and shop, allows for guided tastings from a wide range of Tuscan wines. This is also the best place to study and savour Sienese wines, from Chianti Classico to Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, Brunello di Montalcino and Vernaccia di San Gimignano.

Sienese panforte.

Britta Jaschinski/APA

Via Banchi di Sopra, lined with fine medieval palazzi, is one of the three main arteries of the city centre (the other two being Via Banchi di Sotto and Via di Città). It links the Campo with the splendid Piazza Salimbeni K [map] at its northern end. The grand palazzi flanking the square are the head office of the Monte dei Paschi di Siena, one of the oldest banks in the world. Founded in 1472 and still an important employer, it is known as “the city father”.

Strolling the walls of Fortezza Medicea.

Steve McDonald/APA

Statue of archdeacon Sallustio Bandini in Piazza Salimbeni.

Britta Jaschinski/APA

Basilica of St Francis

From the square, Via dei Rossi leads east to the Basilica di San Francesco L [map] (7am–noon, 3.30–7pm; free). Now housing part of the University, the vast church exhibits fragments of frescoes by Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Next door, the 15th-century Oratorio di San Bernardino (mid-Mar–Oct 9.30am–7pm, Nov-Feb 10am–5pm; charge), dedicated to Siena’s great preacher, contains frescoes by the artists Il Sodoma and Beccafumi.

Here, as at all its far reaches, the city has well-preserved walls and gateways. Siena’s compactness makes these easy to explore, inviting you to wind through the sinuous medieval streets and stumble across secret courtyards, fountains and surprisingly rural views. This perfect, pink-tinged city is a delight to discover on foot, from the shell-shaped Campo to the galleries full of soft-eyed Sienese madonnas. In the backstreets, the city history is laid out before you, with noble coats of arms above doorways, or contrada animal symbols defining where their citizens belong. Everywhere leads back to the Campo, at its most theatrical in the late afternoon, after a day spent in the shadows of the city walls and inner courtyards.

The view east from the Torre del Mangia.

Britta Jaschinski/APA

But to escape the crowds, walk along the walls, or take the countrified lane of Via del Fosso di Sant’Ansano, which runs behind Santa Maria della Scala. Or stroll to Santa Maria dei Servi to lap up equally lovely views en route to a sublime church.

Given its impossibly narrow alleys threading between tall rose-brick palaces, Siena is mostly pedestrianised. Although the city is closed to traffic, visitors with hotel reservations are generally allowed to drive in, if only to park in a designated spot.

Restaurants

Prices for a three-course meal per person with a half-bottle of house wine:

€ = under €25

€€ = €25–40

€€€ = €40–60

€€€€ = over €60

Al Mangia

Piazza del Campo 42

Tel: 057-7281 121

www.almangia.it €€€–€€€€

In a great position on the Campo, this popular restaurant serves classic Tuscan cuisine. Seating outside in the summer. Closed Wed Nov–Feb.

Al Marsili

Via del Castoro 3

Tel: 057-7471 54

www.ristorantealmarsili.it €€–€€€

Elegant restaurant in an ancient building with wine cellars cut deep into the limestone. Sophisticated cuisine, including gnocchi in duck sauce. Closed Mon in winter.

Antica Trattoria Botteganova

Via Chiantigiana 29

Tel: 057-7284 230 €€€–€€€€

Refined restaurant serving fine Sienese cuisine. Specialities include local delicacies, fish and tasty puddings. Closed Sun, period in Jan, early Aug.

Certosa di Maggiano

Strada di Certosa 82

Tel: 057-7288 180

www.certosadimaggiano.com €€€€

This converted Carthusian monastery, now a hotel, serves gourmet food in a magical setting: a courtyard overlooking Siena. Closed Tue.

Da Guido

Vicolo del Pettinaio 7

Tel: 0577-28004

www.ristoranteguido.com €€–€€€

Veritable Sienese institution, set in medieval premises and popular with visiting VIPs. Traditional Sienese cuisine. Closed Wed and Jan.

Osteria del Castelvecchio

Via Castelvecchio 65

Tel: 0577-47093 €€

Converted from ancient stables, this perennially popular hostelry creates contemporary dishes with traditional flavours, including vegetarian dishes. Interesting wine list. Closed Tue.

Osteria Il Boccone del Prete

Via San Pietro 17

Tel: 0577-280 388

www.osteriaboccondelprete.it €

Family-run restaurant serving Sienese dishes in a pleasing setting. Closed Sun.

Osteria Il Carroccio

Via Casato di Sotto 32

Tel: 0577-41165 €

Well run, tiny trattoria serving local dishes. Closed Tue dinner, Wed, Feb and 1 week in Nov.

Osteria La Chiacchiera

Costa di San Antonio 4

Tel: 0577-280 631 €

Small, rustic inn offering Sienese fare – try the local pasta, pici (thick spaghetti), and the pork casserole. Dine outside in summer. Closed Tue.

Osteria La Taverna di San Giuseppe

Via G. Dupré 132

Tel: 0577-42286

www.tavernasangiuseppe.it €–€€

Delicious Tuscan fare in an atmospheric cavern with wooden furnishings. An antipasto is a must; delicious dishes using pecorino. Closed Sun.

Osteria Le Logge

Via del Porrione 33

Tel: 0577-48013 €€–€€€

Set in a 19th-century pharmacy, with authentic dark-wood and marble interior. One of a few gastronomic Siena eateries, it offers dishes such as ravioli with mint and pecorino, duck and fennel, or stuffed guinea fowl (faraona). Montalcino wines from chef’s estate. Closed Sun and Jan.

Pizzeria di Nonno Mede

Via Camporegio 21

Tel: 0577-247 966 €

Serves good pizza and great desserts. Splendid view of the Duomo, which is well lit in the evenings. Book ahead.

Trattoria Papei

Piazza del Mercato 6

Tel: 0577-280 894 €€

Ideal place for sampling genuine Sienese home cooking in large portions. Closed Mon (except public holidays) and end July.

Tre Cristi

Vicolo di Provenzano 1–7

Tel: 0577-280 608

www.trecristi.com €€–€€€

Elegant restaurant with frescoed walls and a contemporary Mediterranean menu. Booking advised. Closed Sun in Aug.

Bars and Cafés

Nannini’s Conca d’Oro (Banchi di Sopra) is an obligatory coffee stop on Siena’s main shopping street. Opposite is Caffè del Corso – chic by day, boisterous by night. Bar le Logge (Via Rinaldini, at the end of Banchi di Sotto) is a non-touristic place to drink cappuccino. On Il Campo, to the left of the Palazzo Pubblico, Gelateria Caribia (Via Rinaldini) offers a multitude of ice-cream flavours. The Tea Room (Via Porta Giustizia; closed Mon) is cosy for tea and cake, or a cocktail with live jazz. Fonte delle Delizie (Costa di San Antonio, near Casa di Santa Caterina) makes delicious pastries. Further from the centre, Il Masgalano (Via del Camporegio, next to San Domenico) is a friendly place for coffees, light lunches or an aperitivo.

In little more than a minute, the Campo is filled with unbearable happiness and irrational despair as centuries-old loyalties are put to the test

Steve McDonald/APA

It is strange how a race that lasts just 90 seconds can require 12 months’ planning, a lifetime’s patience and the involvement of an entire city. But Siena’s famous Palio does just that, as it has done since the 13th century, when an August Palio made its debut. At that time, the contest took the form of a bareback race the length of the city. The bareback race around Siena’s main square, the Piazza del Campo, was introduced in the 17th century. Today the Palio is held twice a year, in early July and mid-August. The Palio, which has been run in times of war, famine and plague, stops for nothing. In the 1300s, criminals were released from jail to celebrate the festival. When the Fascists were gaining ground in 1919, Siena postponed council elections until after the Palio. In 1943, British soldiers in a Tunisian prisoner-of-war camp feared a riot when they banned Sienese prisoners from staging a Palio; Sienese fervour triumphed.

Although, as the Sienese say, “Il Palio corre tutto l’anno” (“The Palio runs all year”), the final preparations boil down to three days, during which there is the drawing by lots of the horse for each competing ward (contrada), the choice of the “jockeys” and then the six trial races – the last of which is held on the morning of the Palio itself.

The words “C’è terra in piazza” (“There’s earth in the Campo”) are the signal to remove the colourful costumes from Siena’s museums to feature in the great Historical Parade.

Steve McDonald/APA

A highlight of the Palio pageantry is the spectacular display of the flag-wavers, famous throughout Italy for their elaborate manoeuvres.

Steve McDonald/APA

The Power of the Contrade

In Siena the contrada rules: ask a Sienese where he is from and he will say, “Ma sono della Lupa” (“But I’m from the Wolf contrada”). The first loyalty is to the city in the head, not to the city on the map.

Steve McDonald/APA

Ten out of Siena’s 17 contrade take part in each Palio: the seven who did not run in the previous race and three more who are selected by lot. Each contrada appoints a captain and two lieutenants to run their Palio campaign. In the Palio, the illegal becomes legal: bribery, kidnapping, plots and the doping of horses are all common occurrences.

Each contrade has its own standard, many of which are displayed around the city during the Palio and play an important role in the ceremonial aspect of the event.

Flags, or standards, are a central theme of the Palio event. In fact, the palio itself – the trophy of victory for which everyone is striving – is a standard: a silk flag emblazoned with the image of the Madonna and the coats of arms of the city, ironically referred to by the Sienese as the cencio, or rag. The contrada that wins the event retains possession of the prized palio standard until the next race takes place.