The Presence of Living Bodies in Space

Developments in architecture and art history

The theme of bodily presence in space is important not only in architecture today, it is topical in a more general way. In fact, that bodily presence is again becoming an interesting topic for architecture today is owed to this more general relevance arising from our current stage of technological civilization.

That bodily presence is given such weight today might seem paradoxical to some analysts. Do we not live in an age of telecommunications? Do our lives not increasingly take place in virtual realms? What could our body mean to us, then?1 Increasingly, people’s social existence is defined by their technical interconnections. Their presence consists less in their personal, physical manifestation than in their connections. Homepage, internet address and mobile phone are prerequisites for the participation in social games. People’s contributions to what happens in society as a whole – to work, consumption or communication – is increasingly handled via the network’s terminals or nodes. For many professional activities, it is irrelevant where the person who practises them is located at any given time – as long as he or she can be contacted somehow. Is that really the case, is this the future of technical civilization: a social existence without a body or, at least, an existence for which bodily presence is redundant?

Many facts contradict this scenario. For instance, travel has not decreased with the expansion of telecommunication but increased. This not only applies to tourism, which has definitely not been replaced by Internet surfing or domestic video consumption – that is the stuff of eco-phantasies. Reality looks different: consumers do not make do with the image but want to have-been-there. This extensive tourism could be regarded as a compensation for an otherwise disembodied working environment, but this interpretation is contradicted by the fact that it also happens at the heart of social development, namely the management of large companies. The prediction that teleconferences – technically entirely feasible, after all – would replace travel has turned out to be wrong. People drive, they fly, they want to congregate: face to face.

Apart from extensive travel, the rediscovery of the human body occurred in parallel with twentieth-century development of modern technology. From philosophy to the mass practices in countless yoga, tai chi, and similar groups, a new human self-understanding concerning the body is beginning to be articulated. This, too, is a paradoxical phenomenon. Do transplants and gene technology not realize l’homme machine (see La Mettrie, 2011)? Has the automation of production not rendered the human body superfluous as a labour force?

Only when applying a one-dimensional concept of technological civilization does this situation appear paradoxical. In reality, this development is deeply ambivalent and can be read like a flip-flop image in two ways. Humans have had their bodies returned to them precisely by technological developments: released from being a labour force, the body potentially becomes the container of personal fulfilment. In fact, the threat to human nature by the technological reproduction of human bodies highlighted bodiliness as a central concern of human dignity. Thus, it was the destruction of external nature that has first brought into discussion the fact that humans are themselves nature.

To sum up: while the basic conditions of our civilization may be technical – within this frame and partially in contrast with it, people insist on their bodily existence and in that way define their dignity, which they demand to be respected, and their needs, for which they expect satisfaction.

Against this backdrop, the renewed actuality of human bodiliness in architecture is not surprising. Architecture operates on both sides, in any event; it is shaped as much by the progress of modern technology as by the development of human needs. Only temporarily and under particular temporal constellations can architects focus on the side of the object, believing that the goal of their construction is properly buildings. Classical modernity was such a period, and particularly the tradition inaugurated by the Bauhaus. Rationality, construction technology and functionality determined building in what appeared to be, from socialist, national-socialist and capitalist perspectives alike, a mass society. The creation of spaces for bodily presence was not regarded as an essential aspect nor human dispositions as an important topic. Nevertheless, that the human body is currently taken seriously again represents a renaissance in architecture, resuming a development going back to the end of the nineteenth century when it was initiated by art historians. Thus, Wölfflin had worked out that the spatial character of architecture is not just a matter of opinion but that it is, rather, experienced in and on one’s body and, in a sense internally matched. This led to the discovery of movement impressions (Bewegungsanmutungen) as essential elements of architectural form. However, Wölfflin not only conceived of existing architecture in its bodily sensory effects but interpreted it, conversely, also as an expression of bodily disposition.2 Thus, he saw the great periods of European architectural history as manifestations of changing bodily self-understandings. August Schmarsow subsequently tried to provide Wölfflin’s intuitions with a psychological base (Schmarsow, 2001).3 Thus, the characterization of architecture was set free from its previous stasis, and architectural works were assessed through the movement of experience. This view was first adopted by Jugendstil (art nouveau) architects. The turn is articulated in August Endell’s book Die Schönheit der großen Stadt (The Beauty of the Metropolis) when he writes: ‘When thinking of architecture, people always think of construction members, facades, columns or ornaments first – and, yet, all that is secondary. Form is not the most effective but rather its reverse: space, the emptiness spreading rhythmically between the walls that delimit it, its liveliness nevertheless more important than the walls’ (Endell & David, 1995: 199f). In Endell’s words, the turn from building to body, from object to subject, is characteristically conceptualized as a paradigm shift from the design of architectural objects to that of space. For architects, this formulation was more meaningful and practical than Wölfflin’s rather phenomenological version or Schmarsow’s psychological one. However radical the change of view was, though, and Endell was right to call it a turn, the relationship was still like that of positive and negative in photography. It stayed within the same dimension and the same metier. Nevertheless, the reversal was a kind of liberation. If the building is no longer the main concern of architecture but the space it creates, inside and out, the perspective is opened up towards infinity, or to ambiguity, as it were.

Spatial structures in bodily experience, architectural forms as movements, architecture as the design of emptiness – with these concepts, Wölfflin, Schmarsow and Endell inaugurated a potential that has in no way been exhausted yet. To the contrary, as mentioned, it was soon covered over again by modern functionalism. But still, we can identify at least three strands along which these impulses were taken up and further developed.

First, there is the detachment of architecture from the norms of horizontality and verticality. This fundamental structure, which permeates all classical architecture theories, takes support and load as the basic pattern of architectural form. This basic form seemed so natural that it was believed to be moored in the human intuitive faculty. Meanwhile, modern architectural developments, as well as psychological experiments, have proven this to be thoroughly wrong. Seeing the world in horizontals and verticals is more likely to be connected with traditional building materials and forms, for example, brick, wall, and load-bearing beam. The new building materials used in railway stations and artificial greenhouse paradises, above all steel and glass, first break with this schema. Interestingly, at about the same time a break with the Euclidean world occurs, if one can put it that way, for instance, in van Gogh’s paintings.4 This development has continued into the present, where it first comes to full flower in the use of materials like steel, concrete, acrylic glass and other plastic materials. They make feasible the jettisoning of straight line, level surface and right angle and thus demonstrate that architecture, rather than realizing a given spatial structure, first and foremost constructs for human experience.

The second main strand is also related to materials, but it now demonstrates a deliberately altered relationship between architecture and space. Mies van der Rohe’s and Frank Lloyd Wright’s buildings,5 above all, have opened enclosed space towards space outside. This risky step into the outside first puts the issue of space on the agenda: in the classical construction of buildings, the spatial sequence always originated as a matter of course, without there being a need for a particular design. The dissolution of the distinction between interior and exterior, however, not only exposes the occupant to the open but, in a sense, also demands that the architect reach out into nothing with his structures. As a consequence, buildings would have elements that had almost no function for their construction or use. One has to admit that this explicit reaching out into space demonstrates in retrospect that architects even of earlier periods have more or less intuitively done the same. Of course, in their case it was hardly a reaching-out into nothing, since it still took place as a practice of urban interior design, for instance, of open spaces in the inner city.

The third strand, which takes up the eruptive potential of 1900 in Germany, was probably inaugurated in the encounter with traditional Japanese architecture. Bruno Taudt stands out for discovering, among other things, the importance of the imperial palace of Katsura, Kyoto.6 Traditional Japanese architecture, with its sliding and translucent walls and its playing down of support and load structures (so that roofs seem to float, columns and beams look like frames), has an entirely different relationship with space than classical European architecture. Space here, it could be said, is already no longer experienced from the side of the thing, and architecture is regarded as design in space. The conscious vacation of centres, the non-centric arrangements of vistas, are also part of this approach. One could say that, by now, such elements have entered modern architecture in general.

Thus, the potential at the start of the twentieth century was taken up along these three strands, even though, it seems to me, it has in no way been exhausted. To the contrary, one could almost talk of a kind of professional damage control regarding the explosion that occurred between Wölfflin and Endell. Architects took up only what they could, as it were, without abandoning their profession. This restriction of potential is already evident in Endell. For when I said earlier that Endell understood the paradigm shift in architecture almost like a positive-negative reversal in a photo, this interpretation allowed the architect to stay with what he knew. The same space that had previously been occupied by the volumes of buildings was now understood as an open space delimited by buildings and structured by their outreaching lines. The question of space itself was still not raised. The issue was still the space of geometry, in which the architect inscribes excluding or enclosing structures. With that, the question of the space of bodily presence – to all intents and purposes already posed by Wölfflin – was still not at all taken up. The architect’s job remained, despite all turns, the work with large, walk-in sculptures.7

What is the space of bodily presence?

Within European culture, there are essentially two spatial concepts, which can both be affiliated with the names of great philosophers and were also shaped by mathematics. The concept of space as topos, place, goes back to Aristotle; that of spatium, distance, to Descartes. Mathematically, topology is the science of a manifold with positional and environmental relationships, and geometry is the science of a manifold with metric ones. According to Aristotle, space qua topos is defined as the inner surface of the surrounding bodies. In this sense, space is essentially delimited, it is something within which one is located, a place. The manifold of places constitutes regions that mutually surround each other. Space in the sense of spatium is the gap between bodies. It is distance that can be traversed or volume that is filled. Both terms, topos and spatium, refer essentially to bodies, and that relates them to each other. Bodies delimit space, or space is the extension of bodies, that is, their dimensions. Space, then, is where bodies find a position and through which bodies move. This conception of space, which I will call summarily geometrical, is natural for architecture, in some sense, given that it has to do with the creation of bodies, namely the erection of buildings. Does this conception of space, however, grasp the discovery of space in architecture as it was conceived from Wölfflin to Endell? Is the space conceived as topos or spatium a space or sphere of human presence? Or, to put it the other way round: is the space of bodily presence the space of geometry?

A human being is, doubtless, also a body among bodies. Humans are subject to the laws of physics, so that two bodies cannot occupy the same place; or that they move through space according to the laws of mechanics. Alive, humans must certainly also deal with themselves as bodies, they have to avoid collisions with other bodies when they move and perform changes of position that consume energy and are subject to the laws of inertia and friction. Humans are bodies among bodies only when regarded as objects – and be it if they regard themselves as objects. In that case, mind you, space is also structured for them as topos or spatium by other bodies. Then, the structures of space are structures of geometry for them, too.

What happens, though, when I assert my human subjectivity, when I query how I experience the space in which I find myself here, or what I experience as space? It turns out that his space is not at all, or definitely not only, structured by bodily relationships.

To start with, I will provide a few examples of spaces in which the experience of being in them is articulated without reference to bodies. At the same time, I note the relevance of that experience for architecture.

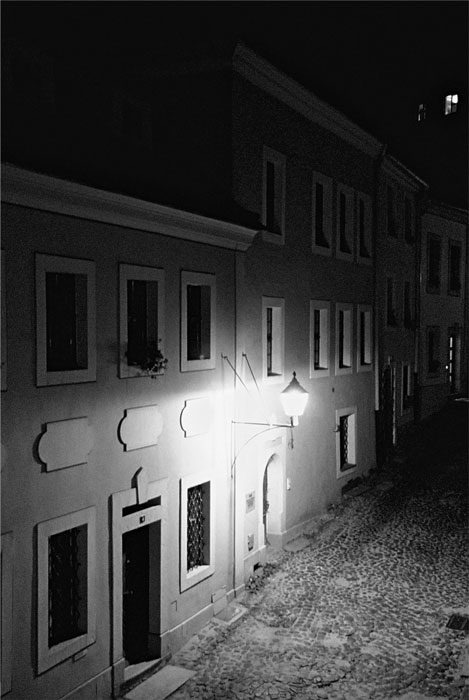

FIGURE 5.1 Street lantern, Görlitz / © 1995 Gernot Bohme.

First, there are light or colour spaces. Everyone is familiar with the experience of being in the light beam of a street lantern or a work lamp. Here, we still speak of a lantern or lamp because we know that this beam has a source, but this knowledge is irrelevant for the experience of the beam as space. What is important, on the other hand, is the contrast with the surrounding darkness and therefore, conversely, the experience of being in the light. This experience is at the same time tuned by, for example, security and homeliness, or conversely by exposure. In any case, the relationship to the surrounding darkness plays an important role. The design of spaces through light, then, is obviously an essential element, which needs to be integrated into contemporary architecture, or has already been taken up insofar as the perspective of human presence is taken seriously. I might add that the classical dogma, that colours are always colours of bodies, does not apply in the design of spaces through light. James Turrell has realized bodiless, hovering colour spaces in his art works.

This phenomenon is related to another worth mentioning, so-called aerial perspective, which is well known in classical landscape painting. While the painted landscape itself could be seen as a bodily structured space, it nevertheless includes something that is bodiless, namely the atmosphere, or air space. Accordingly, we could say that the classical experience of landscape already implied an element that transcended the conception of space as topos or spatium. The experience of landscape thus includes space as the open and indeterminate, as pure expanse. Classical spatial theory has tried to appropriate and thereby restrict this openness in the aerial perspective. The classical example in the context of topology is the interpretation of sky blue as an enveloping body, namely the sphere of fixed stars surrounding us. The experience, or at least our experience, is different – it is the experience of indeterminate vastness. This change vis-à-vis the conception of antiquity is characteristically demonstrated in that famous picture in which a man penetrates the spheres surrounding the earth and looks out into an uncertain outside. Today, we could say that this experience of space (which is, as we have seen, contained in the aerial perspective of classical landscape painting, for example) has its ground in bodily sensing. This means, of course, that the discovery of space formulated by Endell, as the negative of body shape and physical boundary, was still insufficiently determined. This type of space, space qua expansion, can be experienced quite independently of bodies, perhaps even best when bodies are absent or not perceptible. The spaces of night or mist can be such. Certainly, architects can use constellations of objects to render spatial expanse perceptible. It is nevertheless important for them to know that what is experienced in such spaces is itself independent of objects; and it is important to think of other, non-corporeal means to facilitate this experience of vastness. And that leads me to my third example of body-independent spatial experience.

There is an experience with which everyone who has ever been involved with New Music in any way is familiar today – and in the term New Music, I absolutely include both classical and popular music. Developments in music over the last decades have helped overcome the prejudice that music is a temporal art. Spatial installations, events like techno parties, and also new types like ambient music have turned music into a spatial art.8 In this context, the development of reproduction and production technologies was an important factor. Tunes, sounds, noise – as we now know – have their own spatial forms: they move in space, unfurl a space, configure together in space. Such experiences were perhaps already available traditionally, in concerts taking place in gothic or romantic churches, for example. Modern technology now demonstrates that this experience of acoustic spaces can take place entirely independently of bodies or physically shaped acoustic chambers: listening to this kind of music using headphones, one finds oneself in and moves through acoustic spaces. The acoustic discovery of the space of actual experience took place entirely parallel to this development in music. Under the umbrella of the global Soundscape project, research into landscapes and cityscapes as acoustic spaces has been carried out. Acoustic spaces, particularly, were shown to be potentially characteristic of the atmosphere of a city, or fundamental for the sense of home in rural environments. In our present phase, the development of Soundscape flips over from a descriptive to a productive approach. The first projects considering the design of sounds and noise in city and landscape planning are underway.

Disposition

These examples may have already plausibly demonstrated that the notion of bodily presence opens up new perspectives and design possibilities for architecture. Nevertheless, it is important to establish a supporting theoretical background building on the term bodily presence itself. What does bodily presence mean, and what does it mean for architecture that its concern is the design of spaces in which humans will be bodily present?

The question of bodily presence cannot be discussed here fully. In particular, one cannot expect that the question of bodily presence, as an aspect bearing on the work of architects, will at the same time generate an answer to the question why, in an age of telecommunications, people still prefer face to face communication (or, better, communication in bodily presence). In that respect, I can only sketch an idea here that generates a particular perspective on the question concerning bodily presence in space. Telecommunications always relate to specific channels, which means that the partners can only ever communicate according to individually differentiated parameters. This is also the case when partners can see each other’s image on a monitor. As a result, the communicating partners merely appear for each other, like actors on stage. After all, actors are present to the audience only in their roles and not as humans. In bodily communication concerning business or scientific matters, of course, the participants encounter each other as representatives, or in a role, as well. At the same time, however, they are also present as humans. The decisive aspect in bodily communication appears to be that this difference is always in play in communication. That means that an issue or a firm is in a sense incorporated by its representative, who can never simply be identified with a position or a thesis, and thereby categorically checked off – that is, he or she always represents an indeterminate possibility and has to be taken seriously as a person.

We shall see that the significance of bodily presence for architecture similarly hinges on keeping a difference in play, namely the difference between the objective (Körper) and the felt body (Leib). One could say that, until today, architecture has not yet taken up the very theme of the felt body that was part of the turn that was beginning to be felt around 1900. We shall see, however, that the conception of human beings as bodies (Körper) must by no means be abandoned. Rather, the play of difference between objective and felt body is fundamental to the question of bodily presence.

The central term for the description of the phenomenon of bodily presence is disposition (Befindlichkeit). In German, we are extraordinarily lucky that the term sich befinden (to be positioned, to find oneself, to feel) entails an ambiguity that corresponds very well with the phenomenon of bodily presence in space. On the one hand, sich befinden means to be in a space and, on the other, to feel in such and such a way, to be disposed in a certain way. Both meanings are connected and form a whole of sorts: in my disposition (Befinden), I sense what kind of a space I am in.9

FIGURE 5.2 Bruder Klaus Field Chapel (Peter Zumthor), Mechernich-Wachendorf / © 2007 Ross Jenner.

A space, of course, is more than what I sense of it, namely its atmosphere. A space also has its objective constitution, and much of what belongs to it does not enter into my disposition. And, of course, my disposition is not only determined by my sensing where I am; rather, I always already bring moods with me, and stirrings arising from my body also determine my disposition. And yet, there is this centre, this connection between space and disposition, and it is always active and palpable. Disposition, insofar as I sense where I am, generates a kind of basic mood, which tinges all other moods that also come upon me or arise in me internally. We would not normally be conscious of this basic mood as such, but it has nevertheless an extraordinary significance – even when downplayed, repressed, and therefore unconscious – insofar as it has a psychosomatic effect via an organism’s general tone. That is why we need to take atmospheric spatial effects seriously – not only for special occasions, as in tourism or for festivities, but also for our everyday work, traffic and living environments.

So, what is space as the space of bodily presence? The key term has already been mentioned: atmosphere. I prefer the term atmosphere to attuned space,10 since the latter suggests that a space has to be assumed first, which can then take on a mood, as a kind of tinge. Factually, as the three examples above have already shown, the space of bodily presence is an atmosphere into which one enters, or in which one finds oneself (sich befindet). The reason arises from the nature of the experience, which is bodily sensing. And, by contrast with objective, physical space, it is in this sensing that the space we call bodily felt space is unfurled. We sense expansiveness or tightness, we sense uplift or depression, we sense closeness and distance, and we sense movement suggestions. These are some basic moods of bodily felt space as it is given in sensing. They could be expanded into a bodily alphabet, which might be a starting point for spelling out the bodily experience of space (see also Schmitz, 1964). Comprehensiveness, however, is less important here than access to categories of spatial experience prior to any bodily experience. Further, it is important that these categories be, from the beginning, characteristics of disposition or attunement, that is, possess mood qualities. Felt space is the modulation or articulation of bodily sensing itself. To be sure, this modulation or articulation is caused by factors that need to be identified and treated objectively. I call them the generators of atmosphere. Architecture, insofar as it is concerned with the disposition of people who are bodily present in the spaces created by it, will need to take an interest in those generators. They can indeed be of an objective kind, and that is precisely what Wölfflin raised as an issue with his idea of movement suggestions, which emanate from architectural forms. But there are, as the examples show, also non-objective or non-physical generators of atmospheres, like light and sound in particular. They, too, and this merits emphasis, modulate bodily felt space by creating tightness or expansiveness, orientation, and enclosing or excluding atmospheres.

Atmospheres are, as it were, the object pole of bodily presence in space: they are the medium in which one finds oneself (in dem man sich befindet). The other pole is subjective disposition (Befinden), which opens up to an even broader spectrum of characteristics by which atmospheres can be described. So far, I have described atmospheres as bodily felt spaces of presence predominantly through spatial categories that are also characteristic of a disposition, for example, depressing, uplifting, expansive, or restrictive. Expressing a disposition, one might say accordingly, I feel depressed, I feel uplifted, I feel expansive, or I feel restricted. Proceeding from there, one arrives at a type of disposition that need not necessarily be understood in a spatial sense. Or else, its spatial character is not immediately apparent, for example, serious, serene or melancholic. Of course, I have chosen these expressions because they were already used by Hirschfeld in his Theory of Garden Art (2001), in which he described park scenes for English gardens which landscape architects were commissioned to design. Such terms designating dispositions may therefore very well characterize spaces of bodily presence, that is, atmospheres, as well. And that, of course, does not only apply to park scenes, in which, according to Hirschfeld, one can seek out particular moods or find a suitable sounding board for one’s own mood but also to architectural spaces in a wider sense. An interior, a square, a region can appear serene, majestic, frosty, cosy, festive. One can see that a broad spectrum of characteristics of atmospheres, and thereby of spaces of bodily presence, is opened up by the rich repertoire of descriptions of our dispositions. This spectrum may seem confusing and, at first, offer only few avenues for architects to find the generators that lend a space its various mood qualities. A practice perspective, and particularly that of stage design where spaces with a particular mood quality (usually called a climate) are created all the time, might help to create an overview. I suggest three groups of characteristics (or characters, as Hirschfeld calls them) in the first instance: first, movement impressions in a broader sense. In terms of generators, these are above all the geometric structures and corporeal constellations that can be created in architecture. In terms of disposition, they are essentially not only experienced as movement suggestions but also as volume or load, and particularly as a tightness or expansiveness of the space of bodily presence.

The second group are synaesthesia. The term synaesthesia is usually taken to mean sensory qualities that belong to multiple sensory fields at once; thus, one can speak of a sharp sound, a cold blue, a warm light, and so on. This intermodal character of some sensory experiences is grounded in their reliance on bodily sensing, which means that they can be assigned to the respective sensory fields in an ambivalent way only. This becomes particularly evident when one asks about the generators, that is, about which arrangements can produce an experience of such synaesthesia (Böhme, 1991). Once that question is asked, it becomes clear that a room can be experienced as cool, for example, because it is either completely tiled, or painted blue, or else has a comparatively low temperature. What is interesting for architects about synaesthesia is precisely the fact that one can produce the same spatial mood by different means. That is to say, it raises the question for their practice, not of which qualities they should give the objective space they design, but what kind of dispositions they want to produce in that space as a sphere of bodily presence.

Finally, I come to a possibly surprising group, which I call social characters or characteristics. In a way, I have already mentioned one such character, namely cosiness, insofar as cosiness indeed contains synaesthetic elements but at the same time conventional ones. That means that the character of cosiness may very well be culturally specific; or, put another way, what is called cosiness may vary from culture to culture. References to the atmosphere of the 1920s or a foyer; to a petit-bourgeois atmosphere or to the atmosphere of power, however, make the social character of atmospheres even clearer. Architects are well accustomed to dealing with such characters. Of course, they tended to be regarded as important in interior architecture more than in urban planning and construction. Nevertheless, who would deny that architects have always sought to endow their buildings with sacred or grand atmospheres? While these social characters imply, indeed, suggestions of movement and synaesthetic characteristics for example, they also include purely conventional elements, that is, characters that are associated with meanings. The fact that porphyry as a material creates an atmosphere of grandeur, or the nineteenth-century idea that granite exudes a patriotic atmosphere (Raff, 2008), depends on culturally specific conventions. Evidently, there are also elements of a semiotic character among the generators of atmosphere, from materials to objects to insignia more specifically.

Actuality and reality

Concluding analysis at this point could create the impression that the task of architecture is essentially one of staging, given that people will be bodily present in the spaces it creates. In that case, it would be impossible to distinguish architecture from stage design systematically. From that perspective, it would no longer be architecture that is at stake but the staging of spaces of bodily presence, which would convey particular dispositions to their users and visitors. In fact, this moment of staging has recently grown rather prominent in architecture – too prominent as some critics would say. Architectural theorist and historian Werner Durth, for example, remarked critically on the staging of cities already in the 1970s (Durth, 1988). However, simply to equate the task of architecture with staging, in an effort to give subjective perspective and human bodily existence their dues, would amount to throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Architecture will continue to deal primarily with bodies, and it will have to consider humans as bodies too.

Once again, what does bodily existence in space mean? What do people want when they attach importance to being in a particular place, bodily and personally, with other people?

The relationship between environmental qualities and dispositions, which is mediated by atmosphere as the central moment of bodily presence, I have already articulated in detail. This was to draw attention to the actuality of architectures, meaning their effect on a bodily present person. But the third example, above all, listening to music, showed that the associated spatial experiences can certainly occur in virtual space; that means that the respective dispositions can be generated by simulations. This should serve as a warning. Concentrating on architecture as staging, on the one hand, and on the dispositions of visitors and users, on the other, could lead to a world of pure surfaces, accessories, simulation and, ultimately, the virtual. However, to say that bodily presence in certain places, particularly in front of art works and with other people, is important to people only because they want to experience the associated dispositions is, in fact, only half the story. The craving for bodily presence is directed not only towards actuality but also towards reality, the thingness of places, objects and people. One indication of this is the almost obsessive tourist practice of touching, tapping and scratching the buildings and things they visit. Really to be there, then, also means to experience the resistance of things and, perhaps even more important, to experience one’s own corporeality in this resistance. Buildings and spaces are in reality not free and easily available; rather, one has to access them, one has to walk around them, and that takes time and effort. The experience of one’s own corporeality embedded in these acts is, like disposition, central to bodily presence. This shows that the need to feel one’s bodily presence is at once the need to feel one’s own liveliness, to feel vitality. Architecture, consequently, has to continue to provide the opportunity for the users of its works to experience bodily resistance through them. Technical facilities must precisely not be used to render the visit of modern buildings something like effortless surfing.

In summary, traditional architecture has conceived of space from the perspective of geometry and considered the people in it as bodies. In contrast, what matters today is to strengthen the position of the experiencing subject and to foreground what it means to be bodily present in spaces. This aspect will take architecture to a new level of design potential. Neither side, however, should be made into an absolute. Rather, the truth resides in the interplay between the two, between felt and objective body, between disposition and activity, and between actuality and reality.

1See, for instance, Donna Haraway (1991).

2Wölfflin speaks of the ‘Empfindung seines Körpers’, the ‘sentiment of his body’, in the German text (1914: 217). For the English edition, this phrase was rather unfortunately translated as the ‘new outlook upon the human body’ (1952: 231).

3Original publication Leipzig: Hirsch 1897.

4Abandoning the horizontal – vertical schema is not yet the same as a departure from the Euclidean world, of course. However, it becomes clear that the Euclidean approach, as it manifests particularly in the laws of perspective, is nothing naturally given but rather something forged by rules of action, particularly craft rules.

5The surrounding space becomes a natural part of a building’s interior (see Lloyd Wright, 1972).

6This was in the 1930s. Twenty years before Taut, Frank Lloyd Wright had been in Japan, building the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo and absorbing and processing Japanese architectural ideas.

7Sigfried Giedion who, as Wölfflin’s student, was interested in matters of perception, realized in the 1960s that modernist architecture’s sculptural intentions were out of step with the ability of many architects to handle the relationships of volumes. In the Foreword to the 1967 edition of Space, Time and Architecture, he notes that while, in Le Corbusier’s hands, each building ‘emanates and fills its own spatial atmosphere and simultaneously […] bears an intimate relationship with the whole’ (Giedion, 1967: xlvii–xlviii), ‘a building like Ronchamp could be a disaster in the hands of a mediocre architect’ (xlix). Mainstream practitioners ever since have tended to produce walking sculptures, rather than atmospherically charged spaces emanating their own atmosphere and resonating with bodily presence. By contrast, Giedion quotes Georg Bucher’s 1851 description of the Crystal Palace later in the same book: its blue expanse confused the viewer’s sense of distance and, in a ‘dazzling band of light’, ‘all materiality [was] blended into the atmosphere’ (Giedion, 1967: 254).

8See Böhme, Musik und Atmosphäre (Music and Atmosphere, in 1998a) and p. 131ff, below.

9Regarding the relationships between these terms, see Introduction, p. 8, above.

10I have adopted the term atmosphere from Hermann Schmitz (1964), the term attuned space derives from Elisabeth Ströker (1987).