DURING the winter of 1780–81, eleven families recruited from Sonora and Sinaloa set out with their military escort and a phalanx of livestock for Alta California. Along the way they divided into two parties. One proceeded up the coast, crossed the Gulf of California by boat, and then traveled over land through Baja California; another took the livestock along Juan Bautista de Anza’s trail through the Sonoran and Mojave Deserts. The twelve men, eleven women, and twenty-one children converged at Mission San Gabriel over the course of July and August. During August and September 1781, they completed their long journey with a comparatively short eleven-mile trek from the mission to the newly established El Pueblo de La Reina de Los Angeles.1

Felipe de Neve, governor of Alta California, also traveled to Mission San Gabriel from the capital at Monterey to personally mark the new pueblo’s boundaries, designate a central plaza, and distribute house, garden, and farm lots to the settlers. Pleased by the “fertility of the soil” and the “the abundance of water for irrigation,” de Neve located the pueblo near the Río Porciuncula, close to the Pacific Ocean, and adjacent to an independent Tongva Indian village called Yaanga.2 Thereafter, the physical setting played an important part in shaping pueblo residents’ civic ideals, economy, and society.

Between five and ten thousand Tongva already inhabited the broad, well-watered basin. Drawn into the orbit of Spain’s North American colonial enterprise when explorers visited California in the 1500s, Tongva groups had been living in a world shaped by colonialism for more than two centuries. By the 1760s, they had already suffered and recovered from epidemic diseases, and long-distance trade networks frequently brought Spanish goods into the forty to sixty small villages that constituted their community.3 After 1769, renewed Spanish efforts to colonize Alta California again unsettled Tongva lifeways. Fernandino friars both gently and violently coerced many into entering the missions, leaving the work of economic, social, and cultural reproduction to fewer independent Tongva groups. Governor de Neve’s decision to locate the new pueblo next to Yaanga, therefore, created yet another node of culture contact in an already dynamic temporal and spatial landscape.

Although Spanish explorers occasionally visited California’s coast from the 1540s onward, the first permanent incursions began only in 1769–70 with the founding of Mission San Diego and presidios at San Diego and Monterey. Within a decade, seven other missions and two other presidios dotted Alta California’s coast. By the late 1770s, however, the nearly exclusive presence of male colonists had provoked a pressing social and political crisis. Gabrielino-Tongva and other California Indians struggled to understand how Spanish society functioned without women, and Spanish soldiers, steeped in a “patriarchal and ethnically stratified society that devalued females and non-Europeans,” too often treated Indian women “as spoils of war.”4 Their violent behavior “served as a lightning rod for tensions,” swiftly “prejudiced the possibilities for peaceful evangelization, [and] set the stage for heightened conflict during subsequent colonization.”5 The absence of Spanish-Mexican women in the initial phases of Alta California’s settlement thus proved doubly problematic, and “the soldiers’ repeated assaults against native women” imperiled “the entire venture.”6 Men’s sexual and nonsexual violence led neophyte women to flee the missions and partially provoked a bloody rebellion at Mission San Diego and a thwarted uprising at Mission San Gabriel, both in 1775.

In response, Father Junípero Serra implored secular authorities both to discipline male behavior and to stabilize Spanish society by recruiting entire families to the frontier. Serra also asked the government to encourage marriage between soldiers and neophyte women. He argued that the presence of families “would lessen sexual assaults on native women, ease tensions between the Spanish and native peoples, and create a permanent and increasing population of gente de razón.”7 Serra’s request represented only one voice in an emerging “consensus in New Spain in favor of the participation of women in settling the northern frontier.”8 Royal authorities ultimately adopted new colonial strategies, removing legal barriers to marriage between soldiers and neophytes and founding three pueblos in Alta California. Los Angeles’s genesis as a pueblo, therefore, distinguished it from Alta California’s other colonial settlements. Rather than serving expressly religious (missions) or military (presidios) purposes, royal officials hoped the pueblo would offer a social and civic platform from which to stabilize colonial relationships.

Recruiting families to create such a city proved challenging. Although the Crown offered land to work, livestock to husband, and other inducements, de Neve and his lieutenant Fernando Rivera y Moncada struggled to enlist the required number of settlers. The men and women inclined to uproot their lives, settle the frontier, and build a new pueblo generally came forward from the lower ranks of Mexican farmers and artisans to make a go of it in Los Angeles. None came north with any wealth, and only two males out of the twenty-three adults identified themselves as españoles (Spaniards or creoles born to consistently Spanish bloodlines). The rest, according to the 1781 list of Los Angeles’s original pobladores, identified as indias/os (nine), mulatas/os (eight), negros (two), and mestizos (one). “Typical of the dynamic racial and cultural mixture” in New Spain, Los Angeles’s founding families claimed a mix of European, African, and Amerindian ancestry.9

Spanish officials, therefore, drew Los Angeles into existence not on a blank canvas but instead upon a complex social and spatial landscape that bore the scars and cleavages, both deep and shallow, of historical and contemporaneous indigenous-colonial exchanges. Yet the layered colonial and indigenous past served only as the broad framework within which Los Angeles grew from a precarious Spanish settlement into a relatively prosperous Mexican town during its first six decades. Often without guidance from distant centers of political and economic power, Angelenos elaborated on established Spanish law and custom in the arenas of society, culture, and politics, developing locally specific methods for making race, place, and public policy. The pobladores developed an increasingly autonomous municipal government whose underlying civic ideals (molded by local race and gender formations) empowered men to discipline Indians, women, and anyone else who threatened the public good. These civic and cultural practices influenced the ways men and women—Spanish-Mexican and Gabrielino—modified the land, reshaped the municipal footprint, and created new social and physical places.

Although founded predominantly by people who occupied a liminal status in New Spain’s complex social strata, Los Angeles’s founding families adroitly engineered local racial hierarchies that raised themselves out of the lower ranks. At the same time, they distinguished themselves from and marginalized their Tongva neighbors.10 By 1840, Spanish-Mexican Angelenos enforced sharp boundaries between themselves and other mixed/Indian peoples, despite their own mixed ancestry. Reaching for legitimacy and erasing their recent past as immigrants, the pobladores refashioned themselves as californios (Californians) and hijos and hijas del país (sons and daughters of the land). With this local transubstantiation—worthy of any miracle central to the Catholic beliefs that undergirded Spanish colonialism—pobladores “forgot” their own complicated ancestry and forged a new town, one with social, political, and spatial relationships that soon superseded its colonial legacies.11

Inconsistent rainfall and the locale’s general aridity influenced the settlers’ concerns about water use, allocation, and preservation, but the generally favorable environment sustained the pueblo’s growth. After only a decade, Los Angeles’s population increased to 31 families and 139 total residents. Of the heads of household, nearly one-third worked as laborers and another fifth as vaqueros, or cowboys. Six worked at skilled trades, for example, as blacksmith, shoemaker, mason, and tailor. In 1820, on the eve of Mexico’s independence, 61 families called Los Angeles home.12 The population of the pueblo and surrounding areas grew rapidly during the Mexican period, to 2,000 in 1836 and 2,500 in 1844, including Indians.13 Despite the growth, most Angelenos continued to work as laborers or vaqueros, and only a fraction of the populace engaged in skilled trades or commercial enterprises.

Like other pueblos founded throughout New Spain, the town was anchored by a plaza, mandated by Governor de Neve to be “200 feet wide by 300 long.” Four main streets radiated outward from the Plaza, “two on each side; and besides these, two other streets” ran “by each corner.” The corners looked “towards the four cardinal points,” so that the “streets being prolonged in this manner” weren’t “exposed to the four winds, which would be a great inconvenience.” As the city’s physical and symbolic center, the Plaza exercised centrifugal force on public and private life. Much as Setha Low has argued that plazas in contemporary Latin America offer spaces in which people interact in formal and informal ways on a daily basis, Los Angeles’s plaza served as the pueblo’s political, social, economic, and cultural hub.14 The open space hosted numerous festivals, religious celebrations, and secular amusements. De Neve designated the east-facing side of the Plaza as its front, earmarked space for “the Church and Government Buildings,” and reserved lots on the surrounding streets for the pobladores to build their homes.15

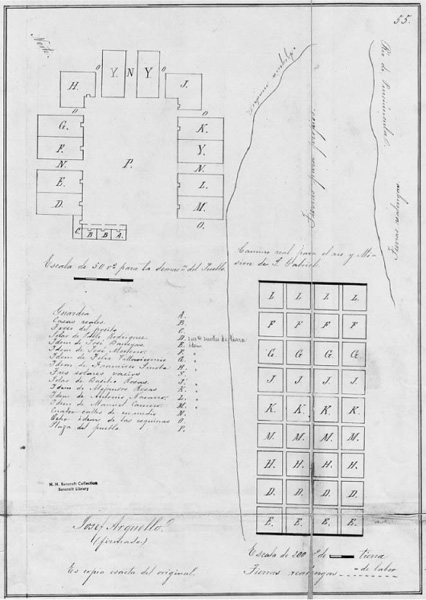

According to de Neve’s founding orders, the pobladores lived and worked close by one another. Their houses clustered together on the streets around the plaza, and their respective farming lots created a single agglomerated rectangle. Watered by a common zanja (irrigation canal), the agricultural plots formed a community garden, with each family tending a small parcel within the larger whole (figure 1.1). It would have been easy to share tasks, divide labor, assess growth, and determine ideal harvest conditions. The layout undoubtedly offered a functional utility by centralizing the location of work and satisfying the Spanish government’s impulse to closely supervise the pobladores. Moreover, these spatial arrangements and the shared work they encouraged likely instilled a sense of common purpose and ensured an even distribution of produce. By keeping house and agricultural lots together and equalizing their size, the inhabited spaces themselves reflected the sense that individual claims did not supersede those of the community.

Figure 1.1. Earliest diseño (map) of Los Angeles, drawn in 1782 by José Arguello. (Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, Banc MSS C-A 2 [Provincial State Papers, Archives of California, tomo 2, fol. 56])

Although the Porciuncula provided plentiful water (estimates suggest it could have supported approximately 100,000 people), its flow fluctuated with the vagaries of the inconsistent climate in Los Angeles. Uneven rainfall sometimes produced blistering droughts, only to inundate the pueblo on other occasions. In 1815 severe floods caused the Porciuncula to change course, which ruined the church. The pobladores responded by moving the whole town, Plaza and all, to higher ground.16 The relocation effort lasted seven years, as city officers had to contend with those who already lived and farmed on the land designated for the new church and plaza. Formerly a perfect rectangle, as per Governor de Neve’s orders, the new Plaza emerged in 1822 as “a distorted, irregular polygon.”17 No royal official had the chance to scold Angelenos for the spatial perversion, however, because Mexico achieved its independence before the new Plaza’s inauguration.

In April 1822—ten months after Mexico’s victory—representatives from each of Alta California’s four presidios, a small company of troops, city leaders, and Los Angeles’s citizens gathered at the new Plaza to publicly swear their allegiance to Mexico. Spain’s colors came down, the flag of the newly independent nation of Mexico went up, and California passed into the hands of new masters. As revolutions go, this one proved unusually mild; even the ceremony lacked the pomp and circumstance customarily affiliated with such an important occasion.18 Some elite citizens undoubtedly regretted Mexico’s victory and the Fernandino fathers openly fretted about what the future held for them and their Indian charges, but no one offered more than grumbling protest. Placid as the change in power proved to be, Mexico’s liberal government did alter the relationship between people and the state. Subjects became citizens, popular political participation expanded, and pobladores found new opportunities to shape the city’s social and spatial identity. Yet differences at first remained below the surface, and most public officials retained their previous positions. For Angelenos, who lived in a thinly populated area far from the new capital, the revolution wrought incremental rather than immediate changes in daily life, which continued to revolve, as it had before, around the Plaza.

Bringing “the formal and informal activities of church and state into a common space,” the relocated Plaza quickly reestablished its spatial and social status as the center of Mexican Los Angeles (figure 1.2).19 Some members of an up-and-coming elite who had received large land grants outside the city limits built town homes nearby. José Antonio Carrillo, many times alcalde (mayor) of Los Angeles, successfully petitioned the city’s comisionado for a house lot with Plaza frontage just southwest of the new church in 1822. Thereafter, Carrillo used this residence when business brought him into town from his ranch.20 Over the next two decades, others followed Carrillo’s lead. Pío Pico became Carrillo’s neighbor in 1834, and most of the elite ranch owners and merchants built town homes that either faced the Plaza or occupied the surrounding blocks by the early 1840s (figure 1.3).21 Working or living close to the Plaza marked high status. Los Angeles’s few independent commercial outlets joined the district’s elite residents. Smiths, dealers in dry goods, and liquor vendors could all be found in the immediate vicinity (figure 1.4). The large open space also served as the principal gathering place for both secular and religious affairs. Angelenos celebrated Corpus Christi there annually, and the pobladores commemorated Mexico’s independence with a party in the Plaza following Mass in 1837.22 In addition to its prominent role in public life, the area around the Plaza served as a primary destination for private affairs, such as family meals and smaller gatherings held in the adjacent homes. Public and private recreational opportunities also abounded. The Plaza often doubled as a ring for bullfighting and bull-and-bear fighting, Pedro Seguro’s private home on the northern corner offered games of chance, and Francisco O’Campo’s giant yard on the southern corner hosted cockfights frequently enough to earn the nickname la plazuela, or the little plaza.23

Figure 1.2. Street Plan of Los Angeles, 1850s. (Redrawn from W. W. Robinson, Los Angeles from the Days of the Pueblo [San Francisco: California Historical Society, 1959], 8)

Figure 1.3. Labeled detail of the street plan showing the Plaza area during the Mexican period. (1) El Palacio, (2) Carrillo Adobe, (3) Pío Pico Adobe, (4) O’Campo Adobe/ Plazuela, (5) Coronel Adobe, (6) José del Carmen Lugo Adobe, (7) Guerrero Adobe, (8) Apablasa Adobe, (9) Del Valle Adobe, (10) Vicente Lugo Adobe, (11) Juan Sepúlveda Adobe, (12) Olvera Adobe, (13) Seguro Adobe and Gaming House, (14) Juan Andrés Sepúlveda Adobe, (15) Catholic Church.

Figure 1.4. Looking east across the Plaza, 1857, one of the earliest photographs of Los Angeles. The two-story Lugo Adobe sits left of center across the Plaza, and the Carrillo Adobe, later Pico House, with its Spanish tile roof, is at far lower right. (This item is reproduced by permission of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, photCL 188 [482])

Los Angeles’s Cartesian footprint and Angelenos’ use of public and private space both reflected and informed developments in the arenas of identity and labor. Race and gender already stood as dynamic axes within colonial society, and ongoing Gabrielino-Tongva engagement with the pobladores created a still more complicated spatial and social landscape. Consequently, the intersection of multiple racial and gender formations shaped the pueblo’s physical and metaphysical contours even before its official establishment. Once pobladores and Gabrielinos began to actively share space, work, and community, the pace of change accelerated and took on distinctly local dimensions. Together they drifted away from both indigenous and Spanish traditions and toward a complex and innovative intercultural society that, nevertheless, proved violent, patriarchal, and hierarchical.

Almost immediately, Spanish-Mexican Angelenos jettisoned official Spanish identity markers. Since the sixteenth century, Spanish law had required census takers to carefully categorize every person in New Spain according to her or his particular blood quantum, creating a bewildering array of more than twenty distinct racial categories that came to be known as the casta system. Although common throughout Spanish America, the prevalence of familial mixing on the far northern frontier and the dearth of “pure” Spaniards sharpened the need to keep track of individual bloodlines while simultaneously complicating the effort. Casta categories ranged from the simple “mestizo,” designating the child of a Spaniard and Indian, to the truly contrived, such as a salta-atras (literally a “throwback”), which designated the child of two phenotypically European parents who looked African or Indian.24 Such an explicit recognition of previous mixing whose knowledge has been lost or erased tacitly conceded the true confusion around these issues.

Royal law reserved positions of influence and power for blue-blooded Spaniards, alternately called peninsulares, españoles, or gapuchines (men of spurs), and their “pure blooded” children born in the Americas, called criollos (creoles). However, very few españoles or criollos lived in Los Angeles or in Alta California more generally.25 The first padrón, or census, taken in Los Angeles contained a racial designation for each of the twenty-three heads of family and their respective spouses. Categories listed include español, indio, mulata, mestizo, negro, coyote (child of a mestizo and an india), and chino (child of a mulata/o and an india/o). Of these twenty-three families, six were headed by couples who had married across categories.26 The children of these mixed marriages, according to the official designations enshrined in the Spanish casta system, would have been officially reckoned as zambos (children from a negra/o parent and a mulata/o parent, seven), chinos, and mestizos (four). María and José Navarro’s three children, who had a mestizo father and a mulata mother, would have been designated calpanmulatos or cambujos had they grown up somewhere else in New Spain.

Having left central Mexico, the pobladores, regardless of their family lineages, found ample opportunities to acquire land and wealth in Los Angeles, further challenging casta barriers. Although Angelenos identified as indios faced the greatest obstacles to equal social standing, “no permanent gulf separated” pobladores “identified variously as español, mulato, mestizo, coyote, and indio.” The lands they received for both houses and agriculture allowed them to achieve a landed independence that remained out of reach for most mixed-heritage people living elsewhere in New Spain.27 The pueblo’s predominantly mixed populace also took advantage of possibilities for upward social and political mobility. Out of necessity, mixed-heritage Angelenos “served as soldiers, officers, and municipal officials.” Because royal regulations reserved public offices for peninsulares or pure Spanish criollos, mestizos who served in such capacity necessarily “climbed” the casta system despite their individual lineages. Several did so immediately: of the eight men on both the 1781 settlement list and the 1790 census, seven improved their racial standing. The only one who didn’t, Félix Villavicencio, identified as español on both occasions.28

Having escaped the casta system’s bonds, Spanish-Mexican Angelenos rapidly developed local strategies for defining race and identity based on a complex relationship between ancestry, actions, and achievement. As they actively redefined their own racial identities and fashioned a new racial system, the pobladores repurposed the simpler Spanish categories gente de razón and gente sin razón to create a clear (but by no means impermeable) boundary between themselves and their Gabrielino neighbors. Literally translated as “people with reason” and “people without reason,” gente de razón used their reason to master nature, whereas nature mastered the gente sin razón. Lacking bodily discipline and the capacity for rational thought, gente sin razón ate when they were hungry, took from nature without dominating it, freely engaged in sexual relations, and performed “magic.”29 In practice, people identified as gente de razón practiced Catholicism, spoke Spanish, lived in towns, worked as farmers, and paid taxes. Strong gender norms and acquiescence to a rigid form of patriarchy further required Angelenos desirous of gente de razón status to uphold nuclear families, “the authority of husbands and fathers over women, sexual purity or virginity before marriage, fidelity and monogamy during married life, chastity in widowhood, and shame in all bodily matters.”30 So long as they “dressed and acted more or less as Spaniards,” people claiming Indian or mixed ancestry could still achieve “rank and status” as gente de razón in Los Angeles.31 This was especially true for Mexican-Indian pobladores who “had moved outside the linguistic and cultural area they had been affiliated with as ‘Indians.’”32 Ostensibly a social and cultural measure of the degree to which any one individual practiced appropriate self-discipline and contributed to the community’s general well-being, razón operated in Spanish Los Angeles as a racialized measure of social position.

Although confident they could teach the Gabrielinos razón, Serra and other Franciscan fathers worried that the establishment of pueblos would threaten ecclesiastical authority. Likely confirming their suspicions, Governor de Neve visited Yaanga, a nearby Gabrielino-Tongva village, while surveying the site for Los Angeles. Crossing the boundary between secular and religious purview, he prevailed upon several Indian youths to convert to Catholicism and stood personally as padrino in nearly a dozen baptisms, creating a personal bond of kinship that integrated him and his settlers into the larger Tongva community. He did all of this without including the friars at Mission San Gabriel, working instead to lay the groundwork for the pobladores (rather than the church) to employ the converted Indians as laborers.33

The settlers quickly elaborated on the governor’s efforts, forging economic and social relationships between themselves and Yaanga’s residents. For example, the pobladores relied on both voluntary and coerced Tongva labor when building zanjas and houses. At first, Spanish laws prohibited independent Indians from living in Los Angeles or entering private houses. Several pobladores nevertheless employed Tongva agriculturalists on a share system, exchanging a third of the crop for labor. Gabrielinos helped plant and harvest the pueblo’s corn and wheat crops in 1784, and reaped “more than 1,800 fanegas of corn, 340 fanegas of kidney beans, and 9 fanegas each of wheat, lentils, and garbanzos.”34 Angelenos employed Gabrielino-Tongva in a variety of other occupations, and their labor proved crucial to the pueblo’s early success.

Encouraged by the fruitful partnership but worried about reports of Indian abuse, Pedro Fages, de Neve’s successor as Alta California’s governor, issued a Code of Conduct in 1787 sanctioning poblador-indio interactions, requiring settlers to respect Gabrielino rancherías (independent settlements), and mandating payment to Indian laborers. Gabrielino-made ceramics and other household goods unearthed in abundance by archaeologists suggest that Gabrielino-Tongva “women worked in pueblo households” and that pobladores pursued trade with Gabrielinos for “prized sea otter pelts and seal skins, as well as sieves, trays, mats, and other articles made of indigenous woven materials.” Although pueblo-dwelling Tongva “were beaten, starved, and abused” as they had been in the missions and presidios, the code put Indians “in a position to make decisions regarding the social and material benefits between mission and pueblo.” Unlike the Franciscans, the pobladores cared little about converting Indians to Catholicism or fomenting changes to their cultural practices, and Gabrielino-Tongva people demonstrated a preference for pueblo life.35

However much Christianized and independent Gabrielinos became incorporated into the town’s economic and social fabric, however, they did not do so as equals. Most remained categorized as gente sin razón, preventing their full participation in public life and leaving them at constant risk of violence and subjugation.36 Nevertheless, the increasing presence of Gabrielinos in Los Angeles during the 1790s “led to considerable acculturation between the Indian and Spanish communities.” Blurring already unstable boundaries, many Gabrielino-Tongva “spoke Spanish and dressed like their employers, ‘clad in shoes, with sombreros and blankets.’” Reciprocally, the pobladores learned to speak the Gabrielino language and, in time, formed mixed families.37 While living in the pueblo generally offered Gabrielinos “greater freedoms and new opportunities,” and “adapting to the emerging mestizo culture” allowed some to rise into the ranks of the gente de razón, most “remained at the bottom of the social structure” and faced marginalization.38 Rather than reproducing the casta system, Los Angeles’s settlers universally reckoned themselves as gente de razón, regardless of their individual origins. In so doing, they debased most Gabrielinos as gente sin razón. For the pobladores, this racial maneuver involved obfuscating their own mixed ancestry and family histories of colonial subjugation while simultaneously denying the possibility that Gabrielino-Tongva could undergo a similar transformation.39

When Mexico gained its independence from Spain, liberal ideologues abolished the casta system and leveled all residents of Mexico as citizens with a vested interest in the Mexican state.40 Although effected on paper with a few quill strokes, many elite Mexicans proved reluctant to relinquish their status. Complicating matters further, Mexican officials launched a corollary effort to disband and secularize the missions. The controversial initiative provoked sharp divisions among elite Californians and led to a decade of debate. Proponents hoped that Indians, emancipated from priestly control, would productively work the land, pay taxes, and contribute to society. Opponents, including remaining mission fathers, argued for a gradual approach as they did not believe the neophytes “ready” to be resituated as independent, productive, land-owning Mexican citizens. After a decade of debate, the territorial authorities, together with the Mexican government, ultimately closed the missions and secularized mission lands between 1834 and 1836.41 According to the plan, former neophytes would receive mission lands and could either remain in their homes as owners rather than charges or leave the missions and go where they pleased.

Once approved, however, California officials failed to implement secularization as designed. Rather than equitably dividing mission property among the former neophytes, they engineered a bonanza for select Mexican Californians. Approximately 800 well-connected men and women snapped up more than 8 million acres of liquidated mission lands between 1834 and 1846.42 In the Los Angeles area, only twenty former neophytes (eighteen men and two women) received grants as part of secularization. None were especially large, and all twenty together totaled 3.5 sitios (square leagues, measured as 4,339 acres or 6.78 square miles each). Moreover, each individual parcel awarded to Indians proved far smaller than the average granted to Spanish-Mexican residents and paled in comparison to large individual grants, such as the five-sitio Santa Ana del Chino awarded to Antonio María Lugo. Rather than a liberal redistribution, secularization effectively dispossessed Indians from their ancestral and mission lands, and tens of thousands left California’s coastal areas for the less populated interior.43

Over time, secularization played a central role in destabilizing and reconfiguring California society, but not in any way its architects imagined. Liberalism made Indians citizens on paper, and secularization provided for their de facto release from the missions’ formal bonds. Yet the secularization plan fundamentally failed to resituate the neophytes as landed petit bourgeoisie, and those who left the missions joined the independent Gabrielinos already living on racherías or ranchos. Los Angeles’s Gabrielino population swelled as a result of secularization. In 1830, only about 200 lived in the pueblo’s immediate vicinity. By 1844, however, nearly 400 lived within the city limits, and another 650 lived in adjacent rancherías.44 Without land of their own, Indians had to hire themselves out as workers in order to survive, leaving them open to predatory employers.

Secularization also fundamentally altered California’s economy. Under Spain, the missions had been the region’s only large economic entities. Although the Spanish government had awarded a few grants to its soldiers in Alta California, secularization allowed hundreds of previously impoverished soldiers and settlers, male and female, to acquire enormous parcels of former mission lands. Most tracts included sizable herds of cattle, and the grantees became ranchers. Concurrently, Mexico’s liberal trade policies opened California’s shores to foreign commerce. Ranch-raised cattle became central to a vigorous international hide and tallow trade, and the rancheros reaped unprecedented economic rewards in the form of specie, social status, and the ability to purchase finished goods from abroad. Consequently, recipients of former mission lands began accruing sufficient wealth and status to nurture claims to elite status among gente de razón.45

The aggregate social and economic consequences of land redistribution and the growing hide and tallow trade further jumbled already fluid identity markers. Razón continued to divide people throughout the Mexican period, but less neatly. Not only did the rancheros begin to separate themselves socially and economically from ordinary pobladores, three generations of mixed families and the infusion of many former neophytes into the local community softened the line between gente de razón and gente sin razón among working people. Indians’ new status as citizens also complicated available strategies for controlling sufficient labor to run the ranches and sort town residents. Thus, too many people existed close to razón’s dividing line for continued clarity, and the connection between razón and status, in turn, became less predictable.46

The newly landed, in particular, needed solutions to these dilemmas in order to leverage their ranches into social and economic advantage. Building on new relationships between land and labor, they invented new categories of social identity and established new markers of difference across Mexican Californian society. The emergent, ranch-owning elite drove these new formations, refashioning themselves as californios (Californians) and hijos del país (sons and daughters of the land), simultaneously erasing Gabrielino-Tongva as the original inhabitants and their own recent familial histories of mixing and migration.47 Among the californios, vast lands, numerous livestock, opulent displays of wealth, and ornate clothing rendered meaningless any individual’s particular lineage. As the californios transformed their identities, they nevertheless reproduced and elaborated a fairly rigid patriarchy that had been brought from Spain and developed in the colonies. Whereas californianas had to engage in an array of domestic chores, obey their fathers and husbands, and conform to strict sexual regulations in order to maintain their own and their familial honor, californio men ensured their status by a culture of leisure, excellence in horsemanship, and control over the family.48

Beyond relying on sharply defined and asymmetrical gender relations, each component of the new californio identity hinged almost entirely on the successful exploitation of other people’s work. Secularization had left many landless Gabrielinos dependent on others for food, clothing, and shelter, and californios drew hundreds of local Gabrielinos into sustaining cycles of semi-and involuntary employment on ranches that reduced many Gabrielinos to peons.49 Outraged, Narciso Durán, Father President of the remaining mission system, complained to Governor Figueroa in 1833. He lamented that the two to three hundred Gabrielino-Tongva he found living around Los Angeles were almost all “servants” of ranchers who knew how to secure Indians’ “services by binding them a whole year for an advanced trifle.”50 On the ranches, Gabrielino women assisted “with the time consuming round of domestic chores,” and men worked in a variety of tasks related to farming and animal husbandry. For their work, they received crude huts for dwelling places; corn, beef, and beans to eat; and payment “in kind, sometimes with aguardiente and at other times with finished goods, such as blankets, clothing, and other items.”51 Although most californios characterized their own relations with Indian laborers as familial, and even if “fiestas, cloth goods, and aguardiente smoothed over the grimy bond,” the relationship nevertheless proceeded unequally.52 To be Indian meant to labor daily, frequently involuntarily.

In Los Angeles, local law stated that any Indian without obvious employment should be declared vagrant, arrested, and fined. If vagrant Indians could not pay these fines in specie, the municipal government employed them on public works projects or auctioned their labor to private citizens. This work offset the fines but carried no additional salary, allowing city officers to round up most Gabrielinos as again vagrant once they were released from service. Through these policies and practices, elite and middling Angelenos imposed an improvised version of labor control resembling slavery.53 As they forged their own racial status, therefore, the californios simultaneously reenacted the same race-making practices to which their own forebears had been subjected during earlier phases of Spanish colonial rule in Mexico. The californios thus built on existing Indian racial formulations to resubjugate Gabrielinos within the new social and economic order, relying on law, custom, trickery, and violence to create and invest with meaning alleged differences between themselves and Indians, sharpening the definition of and differences between californios and indios.

The very work and peonage that defined Indian identity also accounted for the material basis of the californios’ elite economic and social status, as had been the case in the forging of another North American racial system, black African slavery. The asymmetrical relationship of mutual dependency that emerged in Los Angeles diminished the californios’ work responsibilities and provided them with a suddenly valuable economic commodity: cattle hides and tallow. Californios bartered hides and tallow with seaborne foreign merchants for luxury goods, especially furniture, cloth, and precious metals, which in turn increased their material possessions and buttressed their efforts to distinguish themselves from others. Fancy furnishings differentiated the interior spaces of elite homes from those of ordinary Angelenos, and flamboyant fabrics allowed dress to serve as a marker of californios’ and californianas’ status. Rancheros and rancheras also acquired simple cloth and other trinkets that they gave to the Indians. This served both as a form of compensation, reinforcing the unequal labor relationship, and as a further indicator of difference, because Indians could dress only in plain clothes.54 Thus, Californios used dress instead of phenotype as one identity marker. In addition to reinforcing the asymmetry in costume and material possessions, the trade patterns also fixed meaningful boundaries between traders and non-traders. Determining what goods were to be exchanged, on what terms, and how they would be distributed gave a person power in the Los Angeles economy. The californios’ control over possessions reinforced differences among groups and established relationships of power between them.

Two additional social identity categories emerged in Los Angeles during the 1820s and 1830s: vecinos and cholos. Although less clearly defined, either on their own terms or in relation to each other, they nevertheless encompassed the majority of Angelenos. Literally translated as neighbors, vecinos included the city’s thin middle class, skilled ranch hands, independent farmers, and other working, established residents. All of these men and women qualified as gente de razón, but they did not control enough land or labor to pass muster as californios. As members of an intermediate category, vecinos could not claim elite status, but neither did they fear being treated like Indians. Vecinos enjoyed social and political equality in Los Angeles, where they hosted important social events, lived near the Plaza, and held the majority of elective and appointed offices.55

The same cannot be said for those Angelenos classified as cholos. Originally a casta category describing the offspring of two mulatos, themselves children of mixed Indian and African parentage, the term also applied to people living in Spanish-controlled Mexico who had one mestizo and one indio parent.56 Californios and vecinos drew on this epithet with particular frequency between 1825 and 1830, when four hundred “petty thieves and political prisoners” came north from Sinaloa and Sonora. These “cholos” proved particularly “corrupt and lustful,” according to Juan Bautista Alvarado, who complained that “quarrels and struggles among themselves were daily occurrences.”57 Antonio María Osio disparaged as cholos a group of Mexican soldiers from Tepic and Mazatlán—“despicable people” who perpetrated numerous “robberies, stabbings, assassinations, and other actions”—upon their arrival in California in 1819. Osio, a mid-level political operative and fourth-generation resident of Mexico and California, attributed such behavior to the “excesses peculiar to coarse men,” adding that such “depraved practices” were “entirely unfamiliar to the californios.” He concluded by claiming still more broadly that “none” of these immigrants from Mexico to California “behaved with honor.”58 Osio, who arrived in California more than six years after these events, seemingly didn’t need to be present in order to assess the immigrants’ behavior. Categorical and ideological, prefigured without necessary recourse to an actual event, one could know how cholo immigrants from Mexico behaved in absentia.59 The californios didn’t only rail against allegedly base Mexican immigrants in their memoirs, they controlled cholos in much the same way they controlled indios—by subjecting them to vagrancy laws and binding them over for long-term service as peons.

Culture, class, status, and ancestry worked together to build and sustain the new identity categories that emerged in Los Angeles during the 1820s and 1830s. Unlike the United States, where skin tone played a dominant role in marking race, minimal differences in color, language, and ancestry required Angelenos to develop different strategic mechanisms for sorting society’s members.60 Behavior as much as ancestry, occupation as much as religion, and attire as much as phenotype came to determine one’s location within the social hierarchy. Pío Pico, a cattle baron, Plaza-dweller, and California governor, held vast tracts of land, controlled hundreds of Indian and Mexican laborers, and dressed, acted, and engaged in leisure as other elite members of society. It mattered not that his grandparents included a mestizo and a mulata, or that his brother Andrés looked every bit the Spaniard while Pío had dark skin, curly hair, and African facial features (figure 1.5). None of this kept Pico from playing a central role in California’s politics and economy throughout the nineteenth century.61

Pico and his cohort in the up-and-coming Mexican Californian elite engaged in a race-making project designed to overcome the social and economic uncertainties caused by liberalism and secularization during the 1820s and 1830s. Using land and labor as the basis for reconstructing society and the local economy, the californios instituted a layered racial hierarchy that replaced razón as the primary marker of identity in Los Angeles. Increased wealth and control over a new source of labor could not alone facilitate the coherence of new racial categories. Throughout the Spanish and Mexican periods, these racial projects emerged in dialogue with policies shaped by the municipal government and the pueblo’s physical growth, which in turn served to create symmetry between social, political, and spatial practice. Only because of these multiple connections did the set of ideas represented by californios, vecinos, cholos, and indios become invested with meaning.

Figure 1.5. Pío Pico and family. From left: Maranata Alvarado (niece), Nachita Alvarado de Pico (wife), Pío Pico, Trinidad de la Guerra (niece). (San Diego History Center, Negative No. 3544-2)

The elected alcalde and ayuntamiento (town council) formed the nucleus of municipal government in Los Angeles, and their policies guided the pueblo’s development under Spain and Mexico. At the municipal structure’s center stood the alcalde, who served as president of the ayuntamiento, chief executive officer of the municipal corporation, and judge of the first instance.62 Ayuntamientos, consisting of elected representatives, functioned as the pueblo’s primary legislative body and bore responsibility for securing the community’s overall welfare.63 In order to hold elective offices, candidates had to be literate, pueblo citizens, and debt free.

Brought from Spain to the Americas, the position of alcalde originated as an Islamic institution, the qāḍī, or judge.64 In Los Angeles and throughout New Spain, alcaldes oversaw the municipality as chief executives, stood as judges of the first instance, presided over the ayuntamiento, and bore general responsibility to keep the pobladores orderly and harmonious. In their daily duties, alcaldes in Los Angeles issued licenses, inspected hides before sale, issued passports to visitors and travelers, investigated crimes, presided over trials, and mediated disputes. The ayuntamiento had similarly broad oversight. It heard petitions for vacant lands, established and maintained orderly streets, ensured the appropriate distribution of water, limited vagrancy and violence, kept the pobladores productive, and brought citizens under arms when necessary. In a single session, for example, the ayuntamiento established new municipal offices, regulated the carrying of weapons, and outlawed gambling.65 Throughout the year, the city government collected fees, levied fines, and paid various expenses.66

Given the breadth of their responsibilities, alcaldes depended on the community’s respect to effectively wield their considerable powers. According to one scholar, “in municipal matters and local disputes the alcalde’s word was literally the law itself, unfettered by substantive standards (legal rules).” In adjudicating and resolving disputes, alcaldes ruled as they “saw fit, confined only by the cultural and religious mores of the local village in which [they] sat.”67 Consequently, the civic ideals that guided how alcaldes and ayuntamiento members engaged municipal governance, regulated public life, and mediated local disputes played an important part in creating both the municipality’s institutions and the larger network of social, economic, and spatial practices under the pueblo’s official purview.

Alcaldes and ayuntamiento members in Los Angeles relied not on instinct alone but on a mélange of social, political, religious, and economic ideologies to steer their behavior as municipal officers. These ideologies, together with the ways city officers understood the meaning of citizenship and the pueblo’s ideal future, generated civic ideals that both informed and reflected the estimation, formulation, and implementation of public policy. By exploring policy making, the building blocks of such civic ideals and their impact as templates for achieving the public good emerge from the dense labyrinth of petitions, ordinances, declarations, and regulations populating the archival records from the early municipal history of Los Angeles. Although at times disjointed, the strategies policy makers employed in relation to local laws, water regulation, and land tenure collectively offer a view of both dominant trends and key loci of contestation that shaped race and place in Los Angeles.68

Governor de Neve’s founding orders for Los Angeles, and the general laws governing New Spanish settlements, served as the first touchstone for civic ideals in the pueblo. De Neve decreed that all “building lots and planting lands” be distributed “equally and proportionally to all new settlers.” He further reserved all lands not occupied by the first settlers “for propios of the pueblo,” to offset public expenses and to be “awarded gratuitously” to future residents.69 When Los Angeles’s founders received titles to their lands after five years, Governor Pedro Fages (de Neve’s successor) clarified the difference between individual and communal property, “such as the Crops, water, pastures, and wood.” Moreover, “each warrant or act of Possession” contained an explicit enumeration of the limits of each title and recipients’ communal responsibilities.70 The pueblo itself held water and land as common property, and all produce grown on such lands and using such waters similarly belonged to the community as a whole. No individual could ever claim ownership of these resources or use them in any way injurious to the pueblo or the general populace. Alcaldes and ayuntamientos bore responsibility for prioritizing maximal communal benefit and for checking individual abuses.

Clear and concise, these regulations failed to cover the entire ground of municipal governance, requiring municipal officers to create laws pertaining to commerce, cleanliness, behavior, and the use of public space. Checked at times by Spanish officials during the settlement’s early years, the ayuntamientos and alcaldes gained their full independence following the success of the Mexican Revolution.71 As Angelenos became citizens instead of subjects, they took on new responsibilities for determining the direction of municipal governance, and an overall shift in political culture brought both more people and more ideas into the political process. The freedom to participate in public life and invest with meaning categories of citizenship, legal rights, and electoral participation simultaneously allowed Angelenos to create substantive differences through exclusion and inequality. While vecinos experienced dramatic new opportunities to acquire land, vote, and hold office, indios found fewer porosities in the social and political order. Although claiming to hold Indians’ interests in high regard and relying heavily on Gabrielino-Tongva labor, policy makers treated Indians alternately as child-like charges of the pueblo and as threats to the community’s physical and moral health. They used law rigidly to regulate Indian communities, Indian activities, and Indian labor.

City officers similarly treated Mexican Californian women as either charges of or threats to the community, if to a slightly lesser extent. Although women could own property, receive pueblo lots, and engage in commerce, only unmarried women over age twenty-five or widows could do so without their fathers’ or husbands’ express permission. Beyond norms that required young women to be chaste, married women to be faithful, and widows to remain celibate, municipal census takers officially marked women who cohabited with men out of wedlock with the designation “MV,” shorthand for mala vida and indicating women who lived dishonorable lives. Of the thirteen women marked MV in the 1836 census and the thirty-five designated MV in the 1844 census, all were “independent females who often headed their own households.” Although none worked as prostitutes and most lived lawfully, “community leaders saw them as potentially immoral and ‘loose’ women who needed to be regulated and kept under surveillance by patriarchal authority figures.” The group included numerous widows who subsequently connected with other, unmarried men.72 Consequently, the definition of who did and did not count as a member of the community—status based on both race and gender—became central to civic ideals oriented toward a communal ethos.

The idea of communal rights substantively informed the city government’s distribution of the public lands. From Los Angeles’s founding, land falling within the municipal purview belonged to the community as a whole. Individual residents desirous of occupying vacant land petitioned the ayuntamiento, whose standing land subcommittee determined whether or not anyone already held title.73 If vacant, the ayuntamiento offered petitioners provisional grants. Recipients had four months to fence the granted lot and two years to improve and cultivate the land. Once the ayuntamiento’s requirements had been met, the alcalde issued a title. Even then, pueblo rights and communal ideals carried the day. The ayuntamiento granted titles “to the use of the land rather than to the body of the land.” No one held property privately.74 If petitioners failed to scrupulously abide by these rules, they forfeited their lots.

Among the hundreds of petitions for land that occupy the first several folders of the city archives, one in particular suggests the overall ideology guiding the council in its distributive function. Antonio Maria Lugo, a prosperous Mexican Californian and Judge of the Plains, marshaled his intimate knowledge of local civic ideals and prepared a precisely tailored petition for the ayuntamiento on July 20, 1838. He promised to “fence and utilize the land,” close off an alley “only used by wrong doers,” and pay “the taxes imposed” on agricultural products. Together, Lugo rolled the idea of multiple community benefits—fencing off a criminal hangout, supporting the municipal fund, and increasing the aggregate agricultural production of the pueblo—into a single petition. Lugo framed the request as “a benefit, not only to myself, but to the public as well.”75 The council duly granted Lugo’s request but didn’t require citizens to use such forced and obsequious language to secure grants. Several petitions bear only an X, and those preparing the petitions signed others on petitioners’ behalf, noting that the petitioner did not know how to sign.76

Women had access to lands by the same process. Spanish law permitted women, married and unmarried, to own property independently. Only single women over twenty-five years old and widows could purchase, sell, and mortgage property without permission from their fathers or husbands. Several women in the Los Angeles area received or inherited rancho land grants, setting them apart from other women in the community. Ranchos provided them with resources to engage in large-scale commercial transactions and to participate as independent consumers in the local trade in both basic and luxury goods. Many more vecinas petitioned the ayuntamiento for house lots, small farms, and orchards. Although less economically mobile than the local rancheras, land-holding vecinas “nevertheless had the means with which to support themselves and their families.”77 For example, Matilde Cota requested 300 square varas of land for both a residence and a farm in March 1837, which the ayuntamiento granted.78 Most vecinas who applied for and received pueblo lands stood as heads of households, including some who had been marked as MV in the census. Not only did fewer women than men hold town lots, more female than male landowners struggled to complete the improvements necessary to secure titles, because many could not pay for enough outside help to build fences, erect homes, and till garden lots.79

Beyond its control over lands granted for private use, the ayuntamiento tried to control the development of Los Angeles’s public spaces. In 1824, it ordered Santiago Rubio to tear down his house and cede his lot to the city because it was not in line with the relocated main Plaza and the principal street. After a fourteen-year interlude during which Rubio “had not the means to build,” the ayuntamiento compensated him with a new parcel and waived the regular charges.80 While wrestling with Rubio, the council made a broader effort to re-regularize the new Plaza. In 1836 the ayuntamiento appointed a commission empowered to reorder the “streets and plazas of this city.” The commission called for the platting of two maps: one indicating the city “as it actually exists,” and the other with a plan for “the most prudent means of repairing the monstrous irregularity of our streets,” resulting from “the neglect in ceding house lots and erecting houses in this city.” The committee stressed “the importance to this city in having its common lands, streets, alleys, and plazas” kept in good order and asked the ayuntamiento to “act promptly” because the task at hand, “if now difficult, in time will be truly impossible.”81 Although worried about the Cartesian order of the Plaza and its adjacent streets, the ayuntamiento had already helped to establish the Plaza as not only the central space, but also the central place, of public life in Los Angeles. In granting house lots to elite citizens, commercial permits to stores, gambling parlors, and drinking establishments, and in issuing permits for bullfights, cockfights, and public dances along and on the plaza, city officers had engineered the commercial, social, and cultural content that made the Plaza the pueblo’s hub. Moreover, it retained control over that space not only by trying to square the grid on maps but by collecting fees for and regulating the manner of all such activities there.

Municipal officers kept a similarly close watch over pueblo waters. From its founding, few necessities so occupied Angelenos’ attention. Governor de Neve ordered the first settlers to “open the principal drain, or trench, form a dam, and other necessary public works for the benefit of cultivation, which the community is bound particularly to attend to.”82 The construction of this channel, the Zanja Madre, was one of the first two projects undertaken by the pobladores.83 As the steward of the municipal waters, the ayuntamiento oversaw distribution with an eye to the communal good. The principles guiding its decisions grew out of older Spanish traditions, which held that water belonged to the entire community. Irrigating as many fields as possible proved far more important than stimulating private enterprise by allocating great quantities of water to individual petitioners.84 For example, in 1838 the ayuntamiento decided that a spring controlled exclusively by Señora Encarnación Sepúlveda “should revert to the use of the community, which is in need of same.”85 In 1839 the ayuntamiento allowed immigrant Julian Pope the opportunity to “erect a water mill for the purpose of crushing wheat” but denied him a title to the zanja and reminded him that all water he used “must be returned to the same river so that other persons living below will not be injured.”86 Members of the ayuntamiento practiced similar care when communicating to “their superiors that their verdicts had been rendered with the common good in mind.”87 For every irrigation project the ayuntamiento approved, it clarified that petitioners received permission only to use the water, never to own it.

In addition to controlling the water supply, the ayuntamiento oversaw the communal maintenance of the town’s zanjas, or irrigation canals. A standing committee on zanjas supervised repairs and prepared an irrigation schedule. In an 1836 call to “widen, deepen, and straighten” the Zanja Madre and others, committee men Rafael Guirado and Nepomusemo Alvarado ordered that “all the owners of crops and orchards be compelled to contribute, with their person or an Indian to perform said improvement until accomplished.” The committee called on “all owners of crops and orchards” to select “a Zanjero” to oversee the work. The zanjero (water overseer) offered assistance, maintained quality standards, and reported back to the council, which in turn fined shirkers. Moreover, the committee ordered each of the owners to pay the zanjero “from the products of their soil.”88 The order applied to all owners, not simply those on the land affected by the improvements, because the pobladores bore collective responsibility for maintaining the waterways, just as they communally retained rights to the water flowing therein.

Beyond their considerable executive and legislative duties, alcaldes served as judges of the first instance for civil and criminal proceedings throughout the Spanish and Mexican periods.89 In criminal cases, alcaldes examined crime scenes, made necessary interviews, appointed defenders for the accused, and selected hombres buenos (good men) to provide counsel to the interested parties. Alcaldes then presided over formal hearings, consulted with the hombres buenos, and rendered decisions.90 In civil cases, alcaldes acted as arbitrators, mediating between parties to achieve mutually satisfactory resolutions.

In both civil and criminal cases, alcaldes sought conciliatory judgments that fit within communal standards, despite numerous Spanish and Mexican efforts to impose more rigid legal rules.91 In common with municipal governments “throughout the Spanish borderlands,” officials in Los Angeles “preferred to resolve disputes in ways that resulted in the least harm to the community, regardless of an individual’s rights.”92 Justice relied on “culturally based goals of conciliation” and on communal pressures to “compel adherence” to decisions.93 During the first nine months of 1833, for example, Alcalde José Antonio Carrillo heard and issued decisions in nineteen separate cases, concerning debts, petty violence, theft, vagrancy, and the creation of public scandals.94 In 1839, Alcalde Manuel Dominguez mediated a dispute between Justo Morillo and José Sepúlveda over a single piece of lumber. In conjunction with the hombres buenos (Vicente de la Osa and Ygnacio Coronel), Dominguez decided that the “piece of lumber in question belonged to both litigants” and ordered it divided in half “with the only conditions that Sepúlveda deliver” Morillo’s share to Morillo’s “door … in compensation for his [Morillo’s] having done the work of saving the same.”95 Although simple, even obvious, Dominguez’s decision balanced the parties. Equally important, Morillo, an ordinary vecino who signed with an X, found justice against one of the community’s wealthiest and most politically powerful members.

Whereas vecino men found equal footing with those who outranked them socially before the law, vecina and ranchera women did not always fare similarly well. To begin with, women risked dishonoring themselves and their families by initiating a legal or civil complaint against a husband or father, to say nothing of potential retaliation. Nevertheless, women responded to abusive and misbehaving men by turning to the local authorities, who almost always granted requests for hearings. As historian Miroslava Chávez-García argues, women who sought legal redress “did not seek to usurp the husband’s position as the head of the household or to overthrow the ideological and practical system of patriarchy.” Instead, their actions challenged “patriarchal authority figures who had failed to behave according to the gender and social roles prescribed for them.” Moreover, she argues, women who went to court “sought to ensure that the system of patriarchy worked” in their favor. However, “justice frequently eluded” Angeleno women because alcaldes and judges often “interpreted the law in ways that reflected deeply rooted gender biases.” In particular, judicial and alcalde courts almost always tried to protect the honor and integrity of families, a critical, gendered component of californio and vecino society in Los Angeles. Priests assiduously refused to grant divorces, and both ecclesiastical and secular authorities pushed “reconciliation to preserve the marriage for the good of the family and social stability.” Too often, men who committed adultery or acted violently professed themselves changed only to revert to their abusive behaviors. Consequently, women frequently had to choose between renewing their formal complaint, pursuing extralegal measures, or enduring difficult domestic situations without formal redress. Occasionally local authorities punished men, usually in cases involving rape, severe domestic violence, or adultery. Even these penalties had limits, as californio or vecino male violence against Indian women—whose low racial standing left them without honor—often went unpunished or resulted in the levying of fines rather than imprisonment. Many women, despite their ability and willingness to turn to the authorities, found only gentle encouragement to keep their families together.96 Combined with the broader preference for reconciliation, community justice for women meant they frequently struggled to find relief from difficult situations. In all, the intersection of race, gender, and community principles led to systemic biases against all women and especially Indian women.

The preference for “community pressures, rather than force” obtained even in serious criminal cases.97 In February 1837, Alcalde José Sepúlveda decided against executing a group of men convicted of stealing hides. After first sentencing them to death in accordance with formal law, Sepúlveda had a change of heart and meted out a different punishment. Together with the ayuntamiento and “in the interest of humanity,” Sepúlveda ordered the convicted thieves to “apologize publicly for their doings and injuries” before being “paraded afoot through the city’s streets” and banished for life.98 Banishment operated “as a community-based device” that removed “a disruptive influence” and protected the community’s future without the spectacle of a hanging.99 While this apparent weakness may suggest insecurity on the Sepúlveda’s part, offering leniency would not have been entirely out of step with a system designed primarily to manage conflict and preserve community harmony.

Although Los Angeles’s public servants built on and elaborated the basic communal ethos that guided the pueblo’s founding, the policies they chose did not create anything like an inclusive, egalitarian polity. Californios and vecinos normally thought of indios as existing outside the boundaries of their community. Few Indian-initiated petitions for land, claims for water, or civil claims in alcalde court records survive, suggesting they rarely participated in these central aspects of political life. Legal cases involving Gabrielino women and men are more common, and their outcomes bear the marks of race and gender bias. Moreover, policy makers turned widely held notions of Indian difference into institutionalized practices that furthered and substantiated inequality.

Explicit policies established by the Los Angeles ayuntamiento joined the various practices californios and vecinos privately employed to create and maintain Los Angeles’s developing racial categories. The ayuntamiento regularly fretted about the presence of Indians in the city, the possibilities for and consequences of mixing between indios and pobladores, and the seemingly constant threat of violence and social disintegration they perceived indios to pose. In 1833, the council appointed comisionados to “guard and exercise a watchful supervision over the conduct of the aborigines in this neighborhood and report to the authorities.”100 The law made Indians the only group of people subject to observation by any city government official. The comisionado also had the power to round up any Indians considered vagrant and remand them to work either on municipal projects or on private ranches. Consequently, public policy and municipal officers formally supported the californios’ exploitation of Indian labor. Further inscribing racial difference, the ayuntamiento segregated Sunday Mass because “these Indians are a dirty class and on mixing prevent the people from hearing mass, and dirty their clothes.” The council also segregated the city cemetery and buried Indians in a separate area.101 Such acts reflect the ways that californios and vecinos created a highly segmented category for local Gabrielinos, including them as menial laborers but excluding them from full participation in the city’s public and religious life.

Vecinos fared better in the realm of public policy, securing land parcels, water rights, and legal victories, but they acted as junior partners in the making of policy. Since no salary followed public offices, only people who did not require their own labor to survive could serve. Consequently, the system skewed leadership toward people with unusual means, leaving ordinary Angelenos with power only as voters and petitioners. In practice, the alcalde and ayuntamiento—drawn from local rancheros and particularly successful vecinos—administered the community the same way a patriarch or council of elders oversaw an individual or extended family. Enhanced by the general approach to all indios and most women as charges of the local authorities, the agglomeration of each facet of government into the alcalde’s purview produced a communitarian ethos forged in dialogue with local ideas pertaining to race, gender, and patriarchy. Considering the degree to which these structural and ideological elements prefigured Los Angeles’s leadership as male, elite, and paternalistic, the communally based civic ideals sufficiently limited their exercise of power. By no means creators of a utopian paradise, policy makers in Spanish and Mexican Los Angeles nevertheless protected communal interests for those counted as members of the polity.

The founding of Los Angeles brought the human, spatial, and ideological products of a nearly three-hundred-year-old colonial project into competition with an even older and equally complex Gabrieleno-Tongva community. Royal motivations for sending families northward to build pueblos grew in part out of a crisis caused by soldiers’ violence against Indian women. Yet the volunteers who founded Los Angeles and represented Spanish society on this new frontier embodied not pure Spanish heritage but the human mestizaje nurtured over nearly three centuries of contact. Nor did Los Angeles represent a “fresh start” spatially. The orders for its settlement, the Cartesian space of its municipal plan, and the displacement of Gabrielinos living at Yaanga represented only the latest phase of colonial incursion onto Indian social and spatial practices. In total, they carried with them the possibilities and perils bound up in the broader context of Spanish colonialism in Alta California and New Spain. The ethos that led to Los Angeles’s creation, the social dynamics set in motion by the human and historical context of its advent, and the ways its plan and location framed future relationships among the pobladores and between pobladores and their Gabrielino-Tongva neighbors, therefore, emerged within an already complicated colonial stratigraphy, which was itself composed of already fractured and interconnected layers of race, gender, and space.

Within six decades, however, Angelenos had modified social, spatial, and economic relationships, creating race, place, and municipal power on their own terms. Rooted in racial, spatial, and civic ideals, Angelenos harnessed their power to impose, perpetuate, and naturalize new relationships among work, wealth, behavior, sex, and ancestry that corresponded to the new categories of californio, vecino, cholo, and indio, all the while modifying the landscape and displacing Gabrielino villages. To be sure, the stuff of Spanish colonialism, especially in the arenas of the Plaza plan, Indian relations, and rigid patriarchy, remained critical to these new, local formations. Yet the transformation of predominantly low-ranking, impoverished, mestizo pobladores into wealthy rancheros and self-sufficient vecinos who controlled local politics, developed the local economy, and gave shape to social relations suggests the local basis for interconnected racial, spatial, and civic projects.

Growing for nearly sixty years, Los Angeles had reached municipal maturity by 1840. After passing three decades in nearly complete isolation from central New Spain, pobladores had modified their spatial, social, and political environment according to local conditions and experience. Central Mexico’s distance allowed the pueblo a similar measure of independence as its institutions reached young adulthood. During its first fifteen years as a Mexican pueblo, Angelenos reshaped the local economy, civic ideals, and strategies for reckoning identity. It was onto this landscape, already rich in its own local culture, that European American immigrants and the U.S. military ultimately alighted. They brought with them very different ideas about race, gender, civic ideals, economy, justice, and the proper relationship between people, government, and the environment. But Mexican Californians stood poised to negotiate along these axes of difference.

Residents had created place from space on the plain adjacent to the Porciuncula River, laying out a Plaza, building a public church and private homes, and establishing and populating numerous adjacent streets on which they made families, worked, and recreated. As a municipal body, the Los Angeles ayuntamiento adhered to coherent civic ideals that privileged communal over individual rights and favored mediation, arbitration, and compromise over authoritarian rule, complicated by reinvigorated biases against women and Indians. On the whole, Mexico’s liberalizing social policies and mission secularization scheme so blurred identity categories in Los Angeles that its would-be elite opted to remake racial categories and redraw racial boundaries for greater clarity. Whereas the Mexican government moved to level society by abolishing the castas and disbanding the missions, locals implemented these policies in ways that resulted in increased and more intractable inequality. Defining and reinforcing inequality, officials and ordinary citizens created and enforced a suite of harsh policies designed to control independent Indian residents. Saturated as these spaces, ideals, and social identities were with inequality, this surely was no golden age.

Three essential lessons regarding race, space, and municipal power emerge from studying the Spanish and early Mexican period in Los Angeles. First, Angelenos actively engaged their own interconnected race- and place-making projects, and these projects together shaped social and spatial relations in the pueblo from its founding to 1840. Second, phenotype did not determine race in Spanish and Mexican Los Angeles; birth, behavior, and achieved status framed racial identity. Third, the racial categories that emerged during the 1820s and 1830s, however rigid, never became completely fixed—individuals could and did occupy more than one of them in a single lifetime. By 1840, there developed in Los Angeles a complex and nuanced racial hierarchy that shaped society. Space, civic ideals, and racial identity remained subject to dynamic forces, both from within and without. Conflicts between centralists and federalists raged in Mexico City, provoking ongoing political turmoil and a string of small, usually bloodless rebellions in California during the 1830s. These upheavals prevented the new identity categories, and the social and economic relationships upon which they rested, from fully cohering. Those calling themselves californios used both law and custom to make permanent the differences between themselves, vecinos, cholos, and indios, and to invest these differences with lasting meaning. However, their racial cement did not have enough time to set, let alone cure, by 1840, when an influx of traders from the United States and Europe sparked further changes. Despite these challenges, californios and vecinos confronted immigrants from the United States and Europe not as liminal mestizos but as accomplished race makers and empowered agents in the structuring of their own society.