CANNON fire reverberated through the streets, shattering the silence of a rosy Saturday dawn. The opening salvo in a carefully orchestrated Independence Day celebration, the shots called to arms participants in the festivities. By ten o’clock pedestrians and riders filled the streets leading to the Plaza. Members of the Southern Rifles, a local militia group, led the half-mile-long procession away from the Plaza, followed by the Band of the First Dragoons, U.S.A., from Fort Tejon. Falling in behind, carriages carried the mayor, common council, and the day’s appointed speakers. The members of the Masonic order (in full regalia), the Odd Fellows, and Mechanics’ Institute followed in sequence. Three different militia groups—the French Company, the California Lancers (a mounted volunteer militia composed of the hijos del país), and the remaining Southern Rifles brought up the rear. Parading down Main Street to First, then across to Los Angeles Street, they enjoyed the cheers of a large and enthusiastic crowd. After turning southeast onto Los Angeles Street, the procession terminated at the home of Dr. Leonce Hoover, a Swiss who had arrived in Los Angeles in 1849 after serving Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops as a surgeon. On July 4, 1857, he invited the entire town to celebrate his adopted nation’s independence in his orchards and gardens.

At Hoover’s estate, several speakers addressed the crowd. After George Whitman read the Declaration of Independence in English, Myron Norton and Phineas Banning held forth on the history and spirit of independence. Then Judge and City Clerk William Dryden read the Declaration of Independence in Spanish and offered some remarks, which drew “innumerables aplausos y vivas” from the audience. Other guests took the stage as the revelers enjoyed a substantial afternoon meal. By six o’clock the crowd had dispersed to various private parties, with some meeting in the bars of local hotels and others attending a formal ball held by the Southern Rifles.1

Celebrated less than a year after the tumultuous weeks of 1856—when Antonio Ruis’s death and racially charged partisan politics threatened to completely unravel fifteen years of intercultural community development—the Independence Day celebration offered evidence that various Angeleno constituencies had found pathways back to cooperation. Agustín Olvera, Antonio Franco Coronel, and Cristóbal Aguilar served on a twelve-member planning committee that also included notable Democrats and Republicans. Much as Fourth of July events in 1851 and 1852 had provided a forum in which various Angelenos proclaimed themselves members of the same family, the 1857 celebration offered an opportunity to renew that faded spirit. The Star remarked, “A more happy and delighted community we have never seen.” Francisco Ramirez, El Clamor Público’s editor, similarly noted it had “been a long time” since the entire city shared in such an event, awakening “noble memories” of past cooperation. He particularly praised “the great demonstrations of sincerity” with which Californians and others had been included in planning and carrying out the celebration.2

Yet tensions that emerged during the difficult summer and autumn of 1856 along national, social, and political axes had not completely abated. Although open to the public, tickets to the Southern Rifles’ ball cost five dollars, forcing many ordinary Angelenos to adjourn instead to various private homes and public houses. At a few hotel bars, Mexican Californians offered toasts and gave speeches praising the achievements of “their brave parents” for bequeathing to all a “free and beautiful republic.” Some U.S.-born onlookers took offense, giving way to a fortuitously harmless exchange of shouts, blows, and gunfire.3 Nevertheless, the incidents seemed trifling in comparison to the overall unity that prevailed that day and on those that followed. “I cannot explain to you the happiness I experienced at seeing my countrymen beginning to take an active part in public affairs,” declared a citizen at large who submitted a report to El Clamor Público, and he asked God to grant that it would always be so.4 Parties and balls continued until the regular soldiers departed for Fort Tejon on Thursday July 9. The Lanceros and Rifles, together with numerous citizens, escorted them out of town. Just past the city’s edge, everyone “joined in a parting cup. In mutual congratulations, and the interchange and renewal of expressions of regard and esteem, a brief time was passed; finally, amidst cheering and waving of hats, the friends parted, well pleased with their experience of each other.”5

Joining to plan and execute an elaborate July 4 celebration, “in a manner never before seen in this part of California,” required Angelenos to move beyond the physical, political, and social wounds they’d inflicted on each other in 1855 and 1856.6 Even so, the tumult surrounding both Ruis’s death and the city printing contract had produced narrower standards for citizenship and status. These changes in turn influenced the form, content, and tone of the 1857 Independence Day festivities. The Southern Rifles and Los Lanceros de Los Angeles, separate American and Californian militia groups that had formed only in early 1857 as a direct response to the previous year’s challenges, keyed the parade and parties. Organizers also found strategies to control the composition and status of the various gatherings, as all of the key events took place on private rather than public property. In addition, the Southern Rifles and others holding official balls invited the entire populace, but by charging admission they kept those without sufficient cash separate from the elite. Finally, a trope praising the festivities’ good order permeated the reportage of both the Star and El Clamor Público.

Clearly the turmoil of 1855–56 had not immediately undone decades of familial, commercial, and social mixing. However much certain Angelenos may or may not have liked it, they still lived in the borderlands. Many embraced the town’s dynamism and continued finding ways forward together. Despite the recent past, Angelenos during the late 1850s and early 1860s negotiated the kind of place Los Angeles would become, as both public and private citizens. But more than in the past sharp differences arose among those preferring cooperation and those preferring conflict. Consequently, the critical questions to be asked of the people, policies, and places that constituted Los Angeles after 1857 are: where did and where did not intercultural practices survive, and where, how, and according to whose specifications? Did the city heal from fractures caused by the tumult of 1855 and 1856, growing back together even if in a knotty and disfigured way, like unset broken bones, or, to borrow a phrase used by Tomás Almaguer, did the fissures grow into seismic fault lines that threatened to tear the city’s intercultural fabric apart?7 Did Angelenos have more or fewer options or more or fewer opportunities to create new possibilities? National political tensions (which had already produced friction in Los Angeles) worsened until the nation itself ruptured. Locally, the gold rush petered out, cattle prices fell, and a severe drought complicated the answers to these already difficult questions. Each of these crises caused the economic and political ground to shift beneath Angelenos’ feet, making it increasingly difficult to maintain the old balance, even when willing and able partners presented themselves.

The individual decisions of Angelenos that shaped the Independence Day celebration in 1857 represented only some examples of private choices that produced important public consequences. Residents chose whom to marry, where to live and work, and how to educate their children based on personal preferences, but these individual and collective decisions also influenced the occupation and development of the urban landscape, socially and spatially. Los Angeles’s residential and business districts expanded considerably during the late 1850s and early 1860s, driven both by gross population growth and by significant mobility among established residents. Not only did more physical space become occupied, but increased commercial activity also led entrepreneurs to develop new, customized buildings and to demand easier overland passage for their goods and products. Desiring infrastructural change, including the extension of irrigation routes and the establishment of new streets, Angelenos thrust a series of new demands upon the Common Council. While continuing to regulate and coordinate the maintenance, protection, and development of local waterways and byways, the council encountered new questions regarding the limits of its power and the arenas in which it could legislate. When, for example, individuals asked the council for permission to use city waters or city streets within the context of larger commercial ventures, they unwittingly drew the council into new arenas of decision making for which there had been few if any precedents.

Establishing new relationships between citizens, infrastructure, and municipal government would have proved thorny even in the absence of the turbulent events of the 1855 and 1856. In the broader context of Angelenos’ increasing unwillingness to cooperate in the wake of those troubles, however, new commercial practices and their attendant challenges to existing policy regimes further strained the tradition of innovation and compromise that had prevailed since the 1840s. Angelenos—especially those who’d lived in town for more than a few years—continued in their private lives to cooperate, further develop, and elaborate on the local arrangements they had forged during the previous decades. Others proved less accommodating. In public life, even as intercultural civic ideals continued to evolve, they strained to accommodate an ever wider range of different visions for the city’s infrastructure. At times, established residents begged the council to resist any further encroachments on traditional uses for land and water, while the more newly arrived submitted proposals that utterly disregarded established communal practices. The council labored to resolve competing claims and began to depart from its own cooperative tradition by either rejecting or approving proposals without any effort at modification or compromise. Although making for a somewhat messy story, these seeming disparities reflected a growing divergence between choices Angelenos made when dealing directly with people they knew personally and the increasingly distrustful way they confronted each other in the realm of public power.

As private citizens Angelenos made many important, personal decisions indicating a preference for living intercultural lives. The increasingly toxic racial climate of the mid- and late 1850s did not dissuade Angelenos from marrying across erstwhile ethnic or national boundaries, and mixed U.S. and Mexican Californian families continued to flourish. Mixed unions increased during the late 1850s and 1860s, and the children of such unions embodied the very mestizaje that characterized Los Angeles’s social, political, and economic relationships.8 Equally noteworthy, Los Angeles families also chose to send their children to integrated public and private schools. A strong indicator of the willingness of all parents to maintain social contacts across national and linguistic divides, nearly half of the student body in the city’s public school had Spanish surnames in 1860, representing more than 40 percent of school-aged Spanish-surnamed children in Los Angeles. Composed mostly of vecinos, this group remained numerically steady even as the city grew in the ensuing decades and even though the city’s public schools offered instruction exclusively in English.9 A broad cross-section of children from the city’s wealthy families attended private schools, including the Escuela Parroquial de Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles, founded by Bishop Amat and led by the Very Reverend Bernardo Raho, a popular priest. The school’s Mexican headmaster, Pioquinto Davila, taught exclusively in Spanish, but the rolls included children from prominent Jewish and Protestant families.10 While mastering their letters, therefore, a new generation of Angelenos grew up together. Whether in public or private school, Los Angeles parents saw themselves and their children as part of a single community (if at times divided by class), and their children learned a common set of values while speaking to one another in English and Spanish on equal footing. Growing up in shared spaces, children of Mexican Californian, European American, and mixed families in the 1850s and 1860s at least started their young lives with sufficient commonalities to potentially sustain a second generation of intercultural innovators.

Adult Angelenos similarly shared their social and working lives across lines of national origin, if also often divided by class. The Plaza served as a spatial center for convivial meetings and exchanges, both informal and formal. The 1858 Fourth of July celebration paralleled that of 1857, with the Southern Rifles, Lanceros de California, and others staging a parade and the Rifles offering an evening ball to which tickets were again sold for five dollars. Juan Padilla and Andrés Pico joined the organizing committee. A month earlier, a similar coalition helped locals celebrate the festival of Corpus Christi. Following Mass and sermons in the church, the attendees paraded around the Plaza and celebrated in the homes of Benancia Sotelo, Ygnacio del Valle, and Agustin Olvera. They then returned to the chapel for a second Mass and staged a second parade around the Plaza that terminated at the Sisters of Charity. Juan Sepúlveda and W. W. Twist led Los Lanceros de Los Angeles and the Southern Rifles, respectively, which marched in both parades.11 Joining together to enhance a Catholic holiday celebrated in Spanish and Latin, the companies demonstrated a high level of cooperation across linguistic, national, and sectarian lines.

In private houses throughout town, the local elite celebrated weddings, births, and holidays in ample courtyards. The families hosting and in attendance themselves embodied local mixtures of Mexican Californian and European American. On other blocks, including Calle de los Negros (which immigrant Americans renamed “Negro Alley” or “Nigger Alley”) just off the Plaza, working and elite Angelenos gathered in various restaurants, saloons, and theaters, most of which advertised in both the Star and El Clamor Público, indicating their desire to recruit English- and Spanish-speakers as clients. To be sure, violence still imperiled evening revelry at times, and the Star frequently railed against the incivility of local manners and the inability of law enforcement to impose the rule of law lastingly.12 In their emergent associational lives, residents also mixed across ethnic lines to form Masonic, martial, and mutual benefit societies.

As Angelenos continued to use the Plaza intensively for social, civic, and religious activities, they began living physically farther apart. The city’s population increased from 1,610 to 4,385 between 1850 and 1860 as families grew and as immigrants from both the United States and Mexico moved to Los Angeles.13 The newcomers all needed homes, and they had to look for vacant land outside the thickly settled city center. During the late 1850s and early 1860s, two identifiable, and identifiably different, residential districts emerged: one north-northeast and another southwest of the Plaza.

A number of vecinos and immigrants from Sonora, including many who had rushed for gold and subsequently settled in Los Angeles rather than returning across the border, built houses in an area north of the Plaza, adding new adobe structures to those already built by Californian residents in earlier years. Spreading east from Main toward the river and north from the Plaza, the neighborhood stretched out to Yale and College Streets. Joaquín Sepúlveda’s home on Bath Street anchored the region to the Plaza. This district grew throughout the period, and by 1870, 52 percent of Spanish-surnamed Angelenos lived in its ten-block-square sector.14 Locals, especially recently arrived English speakers, came to refer to this area as Sonoratown. Analogous to Chinatown, it was a name at once descriptive and derogatory—a shorthand for a series of stereotypes that cast both the district and its residents as racially mixed outsiders who were in their looks, behavior, and origins different from other Angelenos, despite the fact that many belonged to families who had lived in town for multiple generations. Locals repeatedly linked Sonorans to Indians as savage people, the Star’s “devils incarnate.” Newcomers like Harris Newmark reported “much indulgence in drinking, smoking and gambling, and quite as much participation in dancing” when Sonoratown’s social life was “in full swing.”15

In local parlance, the appellation would have been particularly damaging, as some of the hijos del país likely dismissed Sonoran newcomers as base cholos—gente sin razón. However, many of this district’s residents were not immigrants from Sonora but local vecinos, themselves hijos del país and long-term residents who’d occupied the middling sectors of Los Angeles’s society since the Spanish period. Although few vecinos possessed the cultural and material resources to actively participate in fashioning elite intercultural familial, business, and political relationships, their enduring connection to long-term residents at first kept them from being racially slurred. Yet the 1856 elections and the Jenkins-Ruis affair indicated that Yankee newcomers preferred to lump all of Los Angeles’s Spanish speakers together as ignorant, half-civilized Indians—unless they had enough status and power to prove otherwise. Historian William Deverell argues that the name “Sonoratown” reveals the ways that U.S. immigrants perceived the district—not as one populated by Mexicans but as a local extension of Mexico itself, and one that, in time, required special conquering.16 In this context Sonoratown became one more target for those immigrants who never sanctioned intercultural arrangements; who saw no difference between californios, vecinos, cholos, and greasers; and who remained convinced that brown skin offered ample proof of unfitness for citizenship. The name mattered: living in a place called Sonoratown further imperiled vecinos’ already liminal status in Los Angeles.

The northerly district was more in keeping with the city’s residential and commercial past than the neighborhood that grew up southwest of the Plaza. Most established vecinos lived and operated businesses there from the late 1850s to the 1890s. Moreover, the district provided private and public social, cultural, and economic spaces for the majority of the city’s Spanish-surnamed population, whether they were descendants of Mexican-era residents or recent arrivals. In this context, according to historian Richard Griswold del Castillo, Sonoratown offered Mexican Angelenos a place where they “could feel at home and abandon the masks they wore in the Anglo world.”17 However much living in a place called Sonoratown might have imperiled the vecinos’ status in the city, they built the space in an unapologetically Mexican Californian style dominated by flat-roofed, U-shaped adobe structures that served as both storefronts and residences.

The paucity of European Americans in the adobe-dominated residential district north of the Plaza helped make it possible to call the neighborhood “Sonoratown” in the first place. As a rising tide of U.S. immigrants during the 1850s “cast about from pillar to post” in search of someplace to live, they forged a new residential neighborhood southwest of the city’s center. They built their homes west and south of the Plaza, often along Main Street and past First Street. Since the area had never been thickly settled, newcomers acquired house lots without displacing established residents. Although devoid of graded or paved streets, the newcomers built in a style evocative of their U.S. nativity, putting up wood and brick homes rather than using adobe. Harris Newmark, an early occupant, built “a large, old-fashioned wooden barn” that housed stock, a flat truck, and a roomy hay loft. Although notably diverse, Newmark reported that his neighbors similarly built “frame house[s],” characterized by ample rooms, “wide, high, curving verandas, semicircular bay-windows, towers, and cupolas.”18

As the population swelled and the residential districts spread north and south, commerce also increased. The blocks immediately surrounding the Plaza evolved into a business district, and the variety of entrepreneurial ventures and the spaces in which they operated diversified considerably beginning in the late 1850s. To the traditional array of dry goods, grocery, and liquor stores, consumers in Los Angeles found jewelers, ice vendors, gunsmiths, haberdashers, decorative iron casters, and many others competing for their disposable income by the close of the 1860s. Around the Plaza, many of the old stores remained, and a few residences became shops after changing hands. Several inhabitants in the growing residential district north of the Plaza used the front rooms of their adobes as stores while dwelling in the rear. New buildings dedicated to commerce arose in the blocks southwest of the Plaza, at the northeastern edge of the emerging European American neighborhood.

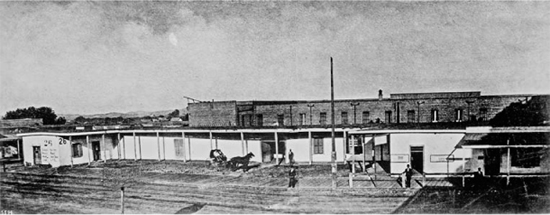

Abel Stearns and Arcadia Bandini de Stearns began experimenting with novel buildings in the 1830s. Mr. Stearns—an immigrant from Massachusetts who had enmeshed himself in the intercultural community—profited handsomely from his willingness to engage in innovative structural practices. Allowing him both to stockpile hides and tallow and to keep an equally substantial store of finished goods on hand year-round, the warehouse Stearns built near San Pedro harbor in the early 1830s served as the physical waypoint between rancheros and seafaring merchants and as an important hinge in the regional economy. By providing the rancheros with specie and fine finished goods, Stearns allowed the californios to host the elaborate parties, don the fancy attire, and act out the high social position central to their identity claims. After their marriage, his wife Arcadia Bandini joined him as a spatial innovator. The couple built a massive house one block off the Plaza on Calle Principal in 1836, dubbed “el palacio” by locals. Besides being home to Don Abel and Doña Arcadia, many businesses operated in the long, low-slung adobe’s front rooms. In 1857, the pair spent nearly $80,000 building Los Angeles’s first U.S.-style business block, a two-story brick building dedicated to commerce. Named after Señora Bandini de Stearns, the Arcadia Block fronted onto both Arcadia and Los Angeles Streets and quickly became “the most notable business block south of San Francisco.”19 Built by an intercultural couple, the Arcadia Block catered to a growing commercial spirit while ensuring that its physical space remained tied to the name of a prominent californiana (figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. El Palacio, the adobe home of Abel Stearns and Arcadia Bandini de Stearns. The brick Arcadia Block (built 1857) can be seen behind El Palacio. (This item is reproduced by permission of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, photCL Pierce 01324)

Slowly, entrepreneurs moved away from mixed-use buildings and into dedicated commercial structures. In early April 1857, Newmark and Kremmer advertised in the Star that they had moved from their old location at Main and Requeña Streets to a “new store, on Commercial street, which has been built and fitted up expressly for them.” They encouraged customers to visit their new, “commodious establishment, handsomely furnished.”20 On the other side of Commercial Street, consumers could also visit Charles Duccommun’s jewelry store, Mateo Keller’s merchandise outlet, and McFarland and Downey’s apothecary.21 Harris Newmark’s brother Marco also moved in 1857, from San Bernardino to “a family grocery store” in a “new and elegant brick building just erected for them” on Main and Requeña Streets, a block south of Commercial Street.22 Jonathan Temple, like Stearns an early immigrant to California who parleyed local connections and business acumen into a small duchy of lands, cows, and specie, built the city’s second business block in 1858. Having profited from leasing the front rooms of the adobe he shared with his wife Rafaela Cota, their daughter Francisca, and her family, Temple separated his home and commercial ventures. He built the brick Temple Block just south of the intersection of Main and Spring Streets, three blocks southwest of the Plaza (figure 4.2).23

Other business owners likewise drifted southwest seeking recent immigrants’ patronage. John Downey took over Temple’s old store and remade it into the Downey Block. The owners of the Bella Union Hotel replaced their old adobe with a two-story brick building in 1857. Prudent Beaudry demolished his wood-framed business row at the corner of Los Angeles and Aliso Streets and replaced it with an ornate brick structure. O. W. Childs also built a new brick building in which to launch his retail business. Men named Perry and Brady built another two-story brick structure. They operated a store on the ground floor, offered the basement to renters as a storage space, and let the upper floor to Masons as a meeting hall.24

The new buildings did not instantly succeed, and many of their builders and tenants faced unexpected challenges. Newmark and Kremmer failed shortly after the move, in 1858. Newmark vacated his custom building on Commercial Street and reopened a smaller store inside the Arcadia Block, where he continued to sell sugar, starch, tea, coal oil, axle grease, bluing, wrapping paper, spices, yeast, blacksmith coal, and a host of other dry goods. Temple’s location at first proved a tough sell to potential tenants as it sat comparatively far from the Plaza. Although Stearns’s prime location brought him lessees immediately, both he and Temple had decided to elevate their stores and storerooms in order to protect them from the Los Angeles River’s penchant for flooding city streets. Seemingly a sensible security measure, potential tenants struggled so to maneuver their merchandise in and out that few renters came forward. Worse still, Temple’s only tenants, Tischler and Schlesinger, lost their cache of wheat when the elevated floor boards gave way and sent the grain cascading into the cellar.25 Temple finally rebuilt his stores flush with the street. That decision, combined with the southwest district’s continued growth, changed the Temple Block’s fortunes and those of the emerging commercial center more generally. By the early 1860s, hatter Daniel Desmond and gunsmith Henry Slotterbeck did good business in the Temple Block’s Main Street storefronts, the local telegraph company rented space on the Spring Street side, and Jake Phillipi operated a small but successful Kneipe, or German pub.

Figure 4.2. Old Temple Block, northwest corner of Main and Spring Streets, late 1850s. (This item is reproduced by permission of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, photCL 188 [569])

Within these new spaces, Angelenos forged and maintained enduring familial, personal, and commercial relationships. Harris Newmark recalled that his business “enjoyed associations with nearly all of the most important wool men and rancheros in Southern California,” including Phineas Banning, John Rowland, Manuel Dominguez, Domingo Amestoy, and Juan Matías Sanchez. Thinking of his store as their own “headquarters,” Newmark noted that “as many as a dozen or more” of his clients “would oftentimes congregate giving the store the appearance of a social center.” The men discussed “with freedom the different phases of their affairs and other subjects of interest. Wheat, corn, barley, hay, cattle, sheep, irrigation and kindred topics were passed upon,” including the weather and the phases of the moon. Often “hours would be spent by these friends in chatting and smoking the time away.” Even though Newmark’s store had changed its physical location and structural form, and even though Newmark and many of his customers traveled between the relocated store and newly built homes north and south of the Plaza, the store itself served as a focal point for both commerce and friendship.26 In other new commercial and residential buildings throughout the city, families, shopkeepers, and customers forged sentimental bonds that knew no boundaries of language, color, or ancestry. Numerous business owners advertised in both the Star and El Clamor Público, spending the time to create separate announcements in English and Spanish to court potential clients speaking either language and keeping Angelenos connected despite the spatial changes.27

By the mid-1860s, then, three identifiable residential and commercial districts had taken hold in Los Angeles. In the blocks immediately surrounding the Plaza, a number of established families—californio, vecino, U.S., and mixed—still made their homes and conducted business. North of the Plaza, a Mexican Californian and Mexican American neighborhood took hold, and an equally recognizable U.S. and European American district emerged to the southwest. Looking back from the present, it’s easy to see the artificers of the intercultural social, political, and economic arrangements of the 1840s and 1850s as both spatially and metaphorically situated in the middle of a town growing apart in opposite directions. But Los Angeles in the late 1850s and early 1860s remained porous; opportunities for new cooperative ventures, public and private, proliferated. The Plaza remained, to use historian Mary Ryan’s phrase, “a durable center of urban space,” even though it no longer stood alone as the city’s core residential or commercial district. The presence of intercultural practitioners at its core offered the possibility of mediation and the potential to negotiate local arrangements anew. Various educational, familial, and commercial ventures of the late 1850s—the mixed marriages, the Arcadia Block, and the public and private schools where children learned language and played together—suggested as much. But the city’s physical, spatial, and commercial spread and diversification also produced new challenges even while offering the potential to resolve older ones. With a broader Cartesian footprint came new demands on the river and the need for new infrastructure in the form of zanjas and streets. Entrepreneurs clamored for more order to the city’s space—the Plaza and the streets on which they hoped to invest capital and erect buildings. Consequently, the very private expansion of Los Angeles’s residential and commercial spaces created very public challenges that the Common Council had to address. The emergence of two new residential districts and the increasing importance of commerce to politically active Angelenos brought issues of infrastructure to the center of the legislative agenda. These issues, innocent enough in their own right, magnified differences in various Angelenos’ civic ideals and put even more pressure on existing intercultural practices to evolve and adapt, especially on those occasions when council members and petitioners proved reluctant to compromise.

William G. Dryden, county judge and the Common Council’s veteran clerk, had a plan. More accurately, Judge Dryden had many plans, but his desire to secure legal right to supply the city of Los Angeles with “pure,” potable water by way of above-ground pipes that led directly from the Los Angeles River or private springs into people’s homes consumed him with a certain passion throughout the 1850s. A lawyer who arrived in Los Angeles in 1850, Dryden served as city attorney, judge in the police court, and for many years as clerk of the Common Council. One year after arriving, Dryden married Dolores Nieto, and following her untimely death he remarried to Anita Dominguez (a daughter of the esteemed Manuel Dominguez) in 1868.28

Few Angelenos witnessed as much municipal politics as Dryden, who served for many years as the clerk of the Common Council and rarely missed a meeting. Fluent in both English and Spanish, Dryden occupied a somewhat privileged position, regarding both information relevant to the direction of city governance and a sense of the mood, reactions, and decision-making proclivities of its membership. In July 1855, for example, having seen an advance rendering of the city map that showed a future street running through land he owned, Dryden persuaded an inexperienced council to pay him $1,000 for the parcel. In making the sale, Dryden magnanimously offered a $500 discount from its assessed value of $1,500 “in order to settle the matter at once.” Despite the discount, the city vastly overvalued Dryden’s land and surely spent above its means.29 Throughout the 1850s the municipal treasury never claimed a cash balance above $4,500 and frequently ran close to empty, as was the case in October 1855 when Dryden’s bill came due. Lacking “funds at present to liquidate” his account, the council offered him interest “at the rate of three per cent per month until paid, interest to be paid monthly.”30 The monthly windfall of $30 generated by these interest payments netted Dryden a 60 percent raise on his clerk’s salary. The gift kept on giving: the city paid him the interest for seventeen consecutive months before he struck a still more lucrative deal in 1857.

Dryden didn’t always succeed so easily. His efforts to win a contract from the city to “improve the distribution and control of the water supply” failed in 1853 and in 1856, despite earning praise from individual citizens and the Star.31 In February 1857 Dryden tried again. By then he had leverage: the city still owed him $1,000. In addition, his renewed effort coincided nicely with significant city government turmoil. The mayor and two city council members had resigned late in 1856. John G. Nichols had replaced Stephen C. Foster as mayor in October, and George Carson and Myron Norton replaced John G. Downey and Ygnacio del Valle on the council on December 30.32 Conveniently for Dryden, both newcomers landed on the Water Committee.

With a new mayor and a new council in place, Dryden’s pipe dream finally came true. In lieu of the $1,000 still owed him, he graciously accepted a thirty-five-acre plot of vacant city land. The grant included the Abila Springs north-northeast of the Plaza (near the present-day intersection of Alameda and College Streets), which were fed by a subterranean flow of the Los Angeles River.33 On February 18, 1857, Dryden petitioned the council for “the right of way to convey Water over the lands of the Corporation” in pipes from his springs for the purposes of distribution to households and business. Councilmen Carson, Norton, and N. A. Potter evaluated the petition and deemed Dryden’s plan “an advantageous arrangement for the City and citizens thereof in general.” Meeting in special session on February 24, the council granted Dryden the right to “convey all and any water that may rise or can be collected upon his lands … over, under, and through the streets, lanes, alleys, and Roads of the City of Los Angeles.” Per his request, the council also gave him permission “to erect and place upon the Main Zanja of this City a Water Wheel to raise water by Machinery to supply this City with water” (figure 4.3).34

Figure 4.3. William Dryden’s waterwheel, late 1850s. (This item is reproduced by permission of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, photCL Pierce 01276)

Dryden’s success effectively changed the fundamental relationship among the municipality, the citizens, and the Los Angeles River on two fronts. First, the council suggested that the waters then circulating in the zanjas lacked integrity and allowed some to be separated out prior to entering town. Second, by conceding to an individual the right to remove a portion of the municipal corpus and the power to redistribute it for profit at his own discretion, the Common Council yielded public stewardship and communal rights to a private entity. Subsequent ordinances clarified the extent of both Dryden’s success and the council’s commitment to the fundamental change in course upon which it had embarked: to make the waterwheel possible, the city ordered the water overseer to extend the Zanja Madre to the edge of Dryden’s land; to help Dryden’s venture succeed, the city supported his effort to secure a sole corporation from the state.35

Once it began allowing objects of municipal control to be turned over to private hands for commercial profit, the council had a hard time stopping. In 1858 Francis Mellus, who operated a wholesale and retail store specializing in hardware and groceries at the intersection of Main and Spring Streets, requested permission from the city council “to place a platform scale for weighing heavy articles in the street in front of his present place of business.” The council not only granted his request, but it further allowed Mellus “to charge the sum of Fifty Cents each and every time the said scale shall be used by persons weighing articles thereon.”36 The town’s growth had required the council to expand its role in maintaining the city streets and regulating the people and products that passed through its byways. Permitting Mellus to charge fifty cents per use, however, carved a new facet into the council’s customary stewardship. City officials allowed Mellus to generate private profit from a public, municipally maintained space, effectively empowering him to use the street in front of his store as a commodity capable of producing additional revenues beyond those arising from his own economic endeavors. The decision followed the precedent established in granting Dryden a private water franchise. With both decisions, the council redefined its role in the local economy. Whereas it had previously limited its purview to preserve the order, regularity, and cleanliness of the city’s streets and zanjas for efficiency and ease of use, the council now intervened to produce privately advantageous economic outcomes. The move reflected a continuing shift toward civic ideals that viewed the municipal waters and streets as themselves commodities capable of generating profits above and beyond communal benefits.

Mellus wasn’t alone in viewing the streets in the city’s central business district as both thoroughfares and commodities, nor was his scale the only incidence of city council forging partnerships with private businesses. In 1859 Jonathan Temple expanded his influence on Los Angeles’s commercial and architectural character when he persuaded the city to lease from him a two-story building designated as the public market house. Temple offered to pay $30,000 to build the public market in exchange for a ten-year lease agreement with the city, in which the city would pay as rent 1.25 percent of the costs each month ($375). Temple also asked the city to concede the lot on which he built the Market House, offering as an inducement the use of one space inside the building as a new meeting hall for the council. Temple built the Market House on a small strip of land adjacent to his business block, and the building paid homage to Temple’s Massachusetts roots; it was modeled after Boston’s Faneuil Hall and featured a wooden cupola and clock above the second story (figure 4.4). Having entered into the agreement with Temple, the city passed an ordinance requiring “all Butchers and Green-grocers to sell their wares therein” in order to generate a revenue stream sufficient to offset the lease terms.37

Figure 4.4. Looking southeast across Los Angeles from Fort Hill, 1868, a view that includes the Market House (right, with clock) and Temple Block (left), with Market Street between them. (This item is reproduced by permission of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, photCL 188 [503])

Whereas Dryden, Mellus, Temple and others actively demanded the council’s cooperation in their personal schemes, the expansion of the city’s commercial and residential districts also put passive pressure on the Common Council to make infrastructural improvements. In particular, locating, opening, ordering, and maintaining city streets became a chief consequence of private growth. In December 1856 the county surveyor re-marked the official lines of the Plaza. Seven months later, the council passed an ordinance mandating “the numbering of certain streets and blocks upon the City Map.” In April 1858 the council ordered the Committee on Streets to “examine all streets, lanes, and Alleys, as far as practicable, and give them appropriate names, [and] also to declare their width and extension,” as a precursor to a series of ordinances making such names and locations official.38 Over the course of the 1858–59 session, the council embarked on a series of street-related initiatives, including the erection of a $3,120 culvert along Los Angeles Street—among the most expensive projects the city had funded to that point. The council paid nearly as much to regrade Los Angeles, Alameda, Main, and Commercial Streets just south-southwest of the Plaza, where a suite of new businesses had sprung up.

Lacking the power of eminent domain, the street commissioner and city council struggled to remake existing streets, as cost prohibited action. For example, a group of merchants petitioned the council in July 1857 to extend Commercial Street, located three blocks southwest of the Plaza, so it could connect to all the major roads passing into, above, and below the Plaza.39 Notions of private property, however, had thoroughly permeated local civic ideals, and many of the owners over whose lands the new street would have run demanded damages. Jonathan Temple set his price at $8,000, and Francis Mellus asked for $10,000. Manuel Requeña, whose lands would have been bisected by the expansion, required the construction of parallel seven-foot-tall brick walls on either side of the proposed street where it would cross over his property. Instead of asking for compensation, Ralf Emmerson flatly refused to surrender any of his property whatsoever to the new street.40 These demands greatly exceeded the city’s available resources. Compromising with a few owners, the council ultimately completed half of the project, extending Commercial to the east as far as Alameda. In May 1858 the city again tried to reshape the streets southwest of the Plaza. To enhance the flow of commercial and consumer traffic, it hoped to redirect the northwest line of Los Angeles Street away from its dead end into Arcadia Street so it could join Calle de los Negros, offering a smoother connection with the Plaza. The council, however, failed to persuade the interested parties to sign on and tabled the measure indefinitely.41

Just as the expansion of the city’s residential footprint required new street initiatives, residents in the new northern and southwestern neighborhoods demanded new zanjas for domestic, agricultural, and commercial purposes. City governors struggled to balance civic ideals mandating equitable distribution and municipal control with newer notions of private use and ownership—including the notion of municipal liability for damages—championed by both U.S.- and Mexican-born residents.42 As it reconsidered its relationship to property owners, the council also fielded petitions from residents who sought nonagricultural water privileges and experimented with new strategies to extend the municipal supply. Paralleling its efforts to improve city streets, the council attempted to get out in front of the town’s geographic and demographic growth. Mayor John G. Nichols pushed the council to effect “several improvements,” by building a new dam four miles up the river, carrying the water through the foothills, and delivering it through a dramatically augmented zanja network.43 The Star cheered the project as both “feasible” and “lucrative.” Promising to add “untold value” to land, “which at present serves only for grazing,” the resultant fertile district would “vie, in the loveliness, beauty and magnificence of their alamedas, parks and pleasure grounds, with the most attractive places on the face of the whole earth.”44

The council appointed N. A. Potter, a former councilman, Manuel Requeña, many times alcalde and president of the common council, and Stephen C. Foster, former mayor, to join Mayor Nichols and the Water Committee in overseeing the project.45 The group established a water fund supported by a new tax of fifty cents per irrigated acre, commissioned plans, and secured an additional $1,000 to pay for a new “dam across the Los Angeles River.”46 In late February 1858 the council passed an ordinance “establishing the contribution that shall be levied upon individuals receiving water from said canal, and the days work that may be received in lieu of money from said persons,” upholding Spanish and Mexican traditions by which labor could be offered instead of cash.47 By the time Mayor Nichols won another term in May 1858, the project had been completed. Still unsatisfied, Nichols used his annual message to push for still more change. He insisted the council give its “immediate attention” to further extending “the limits of irrigation” in order to convert “a large extent of the domain of the city, which is at present waste and unproductive” into “valuable vineyards and garden lots.” Much as the Star had a year before, Nichols thus clothed his appeal in the garments of capital exploitation, the noble calling to convert “wasted” land into a commodity that produced other commodities.48

As in its effort to reshape the city streets, the council met fierce resistance from a slew of U.S.- and Mexican-born Angelenos who actively pursued financial compensation for lands affected by the new dam and zanja project. Since the town’s founding, waterways that benefited the entire community had held right of passage over all lands, and owners had to adjust accordingly. Yet the sheer number of petitions for damages suggested that residents neither accepted the municipality’s power to reshape the landscape nor completely subscribed to the ideal of communal benefit. In separate petitions, Nieves Ruis, Juana Alvarado, and Josefa Sanchez demanded cash compensation for “damages caused” to their lands “by the passage of the new” zanjas. They received $225, $60, and $100, respectively.49 Each of these women was born in Mexican California, and each one, by 1858, had been widowed and thus controlled her own property. Their claims reveal the complicated connections between identity and civic ideals that had developed by the late 1850s. Having come of age under Mexican government, these women felt confident of their standing as equal petitioners before the Common Council and sure of their rights to independently own and oversee property.50 Yet the same experience should have made them intimately familiar with communal ideals governing water use, distribution, and irrigation networks that remained relatively fixed through the early 1850s. Nevertheless, by 1858 they had reinterpreted their own prerogatives as property owners through the newer ideal of private right held not in concert with but against that of city, leading to their successful damage claims. The council also had learned from past experience and had raised enough funds to indemnify petitioners and complete the new water network.

A cadre of private citizens eclipsed even Mayor Nichols’s ambition for the commercial future of the Los Angeles River. A spike in petitions seeking permission for private water-based enterprises during the late 1850s suggests that William Dryden’s water franchise served as an entering wedge for all kinds of schemes relative to water, commerce, and infrastructure. Hiram McLaughlin, who had already received permission to erect an iron foundry and turn its machinery with waterpower, won election to the City Council in May 1857. Only three months later, he asked the council for “a concession of the right of all the fall of water in the Main Zanja, from his present Mill sight down as low as Aliso Street.” In exchange for the privilege he offered to deepen the canal, but he made no mention at all of the potential consequences to other citizens. Another member of the 1857–58 council, Joseph Mullally, asked permission to build a hydraulic ram from which he would draw water out of the zanja to make bricks, which he justified as “a public benefit.” In March 1858 John Griffin became the third sitting member of the same council to ask for a special water privilege: permission to place “a water wheel, which will not impede or interfere with the zanja,” on the back of his lot. Even the parish priest of the Catholic church asked the council for permission to install a ram to draw “one half inch of water” into the church’s yard in order to satisfy “the want felt by” his parishioners.51

As is so often the case with a sudden embrace of new technology, the rush to install machinery in various zanjas didn’t proceed smoothly. Hiram McLaughlin several times agitated local officials for failing to adhere to older policies that didn’t encompass waterwheels and iron foundries. According to the terms on which the Common Council granted McLaughlin permission to build his works, he had to complete the entire building before he could begin putting the water to productive use or receive a deed to the land upon which the structure sat. Moreover, the council explicitly told McLaughlin that his privileges would be “subject always to the paramount right of the use of the water … for the purposes of irrigation,” and further that “his heirs and assigns, shall never interfere with the free use of the water aforesaid for the purposes of irrigation.” For two years, McLaughlin struggled to complete the project and comply with local laws. In December of 1857 Mayor Nichols and a special committee rebuked him for beginning to build before receiving specific guidelines regarding the foundry’s construction. Rather than work toward a compromise, however, committee members Juan Barré, George Whitman, and Antonio Franco Coronel, together with the city attorney, tore down what McLaughlin had already built and forced him to start over. Six months later, McLaughlin again ran afoul of local officials. His iron foundry so slowed the water’s passage that water levels upstream had risen by eighteen inches, breaking banks, flooding bridges, and damaging property. Outraged, the council targeted McLaughlin in a new investigation and called for the city attorney and a special committee to “proceed immediately” with a complete survey of the river and all zanjas “and thereafter report, all works in progress therein and by whom.”52

While the appointed officials did their work, another petition arrived in council chambers. Benjamin Eaton, the city assessor, requested “the privilege of pumping … a body of water … through a two inch pipe,” offshoots of which would be laid along “the public streets” in order to bring water to “residents of this City who have no wells and are obliged to haul their water for household purposes from the zanja.” Beginning near McLaughlin’s iron foundry, his pump would have lifted the water thirty to forty feet above grade into a thirteen-thousand-gallon reservoir from which it would be distributed to Eaton’s customers. In exchange for the requested rights, Eaton offered to build and supply numerous fire hydrants free of charge and to “supply gratuitously all the public buildings of the City.”53

Eaton’s timing couldn’t have been worse. He asked for a privilege that would have placed him in competition with Dryden’s existing pipe plan. Although the offer to help the city in case of fire and to supply the public buildings gratis may have been attractive, it marked the sixth request to use the zanjas for purposes other than irrigation in eighteen months. And his request came just as the council had decided to audit all such schemes. Cristóbal Aguilar, reporting in Spanish for the Water Committee, flatly rejected Eaton’s petition. He wrote that the “machines that have been placed” in the zanja had not “ceased to be some kind of inconvenience.” Moreover, Aguilar argued that if the city complicated the already troublesome “business of placing hindrances in the zanja” by starting “to concede inches of water every so often,” the result would be “a grave prejudice against agriculture.”54 The other committee members supported his position, and the council accepted the decision without further discussion.

By their absence, words missing from both Eaton’s request and the Water Committee’s rejection suggest challenges to intercultural civic ideals. Eaton failed to offer even a formulaic aphorism promising to protect either the municipal supply or local irrigators. Nor did the Water Committee or other councilors try to balance Eaton’s request with countermeasures protecting the water supply’s overall integrity, a precedent that guided other arrangements, including McLaughlin’s contract with the city. Aguilar had decided the river and zanjas could not effectively serve multiple purposes, judged irrigation more important, and deemed any corrective admonitions insufficient to subvert the challenge. Looking out on a cyborg river suddenly full of alien machines, Aguilar and the Water Committee didn’t see a pathway to compromise. Fearing that the city had already turned away from agriculture, Aguilar and his Water Committee rejected Eaton outright.

During the 1840s and early 1850s, both petitioners and council members actively sought middle courses and solutions that productively accommodated multiple civic ideals. By the late 1850s, however, private parties and public officials proved less inclined to recognize the plurality of ideals. Eaton’s failure to accommodate irrigation in his petition and the council’s unwillingness to negotiate provide only one example of the tensions created by the multiple and often competing ideals upon which various individuals built their efforts to influence the city’s space and infrastructure. The stern tone of Aguilar’s broader warning coincided with Angelenos’ perceptions of the heightened import and consequence of streets, water, and infrastructure, indicated by the contentiousness that permeated numerous subsequent decisions. Seemingly, the time for compromise had passed.

Indeed, the city’s physical spread and the increasing number of residents looking to remake Los Angeles’s infrastructure to serve new purposes created new animosities. While trying to defend his iron foundry project from extreme municipal scrutiny, Hiram McLaughlin spent most of 1857 waging a heated political battle against the city zanjero. McLaughlin first chased A. D. Gass from the position and then charged his replacement, Jeffrey Brown, with “partiality and favor in the distribution of Water to William Wolfskill, Matthew Keller, and others.” After a full hearing, the council voted narrowly to keep Brown on as zanjero and rejected McLaughlin’s claims.55 Also in 1857, council president Manuel Requeña lost his temper following a heated debate over ten feet of land on Aliso Street. Utterly infuriated, Requeña stormed out of the chamber, vacated his position, resigned from office, and withdrew from public life for the next seven years.56

Private petitioners proved equally prickly. Fifteen ordinary citizens with English and Spanish surnames living just southwest of the Plaza objected to Mateo Keller’s effort to change the course of two zanjas in order to establish a water-powered mill. Their petition paired a traditional concern that potentially diminished irrigation would harm the perilous productivity of the residents’ sandy lands to a far more novel argument. Referring to themselves as vecinos, they contended that Keller and his partners should be considered “without rights” as “a minority” seeking undue private benefit.57 In another petition, five irrigators (Michel Clement, Tomás Rubio, Francisco López, Martín LeLong, and José Rubio) forced to receive water from a new zanja because of a new waterwheel asked that they instead “be left to take the water from the same place that we have always used and through which we have benefited without causing bother or prejudice to the public good or our own.”58 Both petitions opposed the consequences of new machinery and claimed that irrigators and agriculturalists represented and embodied the general public benefit. In both cases, the petitioners resisted change. Although a majority of the signatories bore Spanish surnames and both groups submitted their respective petitions in Spanish, neither group of petitioners nor the petitions they produced tidily correspond to nationality, political preference, or any other handy schema. Both groups definitively favored the primacy of irrigation as already in place, and both fundamentally asked to be left alone—to remain unaffected by changes foisted upon them by a city council in partnership with newcomers looking to use municipal waters to turn machinery. Interestingly, neither group offered any sort of compromise or middle course.

Taken together, these moments of unease—fracases in council affairs and petitions claiming prejudice—suggest that intercultural spatial and political practices had become profoundly strained by the late 1850s. Although standard in matters of city government, claims of favoritism and partiality surged in lockstep with both a new dynamism in the city’s infrastructure and a general move away from compromise and integrated solutions. Perhaps both the sudden unwillingness to cooperate and a parallel disposition to claim injuries of inequity resulted from the very asymmetries created by overlapping civic ideals and intercultural infrastructural arrangements. Despite the possibilities for compromise and innovation that characterized social relations during the late 1850s, Angelenos spent much of their political energy during that same period playing an increasingly all-or-nothing brand of municipal policy making, especially concerning infrastructure. Less willing to navigate new, more complicated borderlands, ordinary citizens and municipal officeholders expressed anger, frustration, and single-mindedness instead of searching for new common ground.

As it tried (and often failed) to meet Angelenos’ growing demands for more and better streets and for freer access to more water, the city found itself on shaky ground. Some residents resisted both municipal encroachment on private property and water-use plans that competed with existing agriculture. Others—hoping to cultivate new lands, turn new machinery by means of water power, and carry people and products to and from the central district—demanded new streets, an increased capacity for irrigation, unusual water privileges, and new civic ideals to guide municipal authority over land, water, and public space. In seeking a way forward, elected officers and independent citizens placed as much pressure on local civic ideals as the city’s speedy physical growth had placed on its infrastructure. Old questions regarding the meaning of private property and proper uses of the Los Angeles River emerged anew, joining fresh uncertainties regarding the limits of municipal power over city space.

Although residents prayed for and the council granted a series of major capital-intensive infrastructural improvement projects, neither elected officers nor their constituents seemed to completely anticipate the resources, both financial and legal, required to succeed. The city never had much luck raising funds by way of taxes, lacked a home rule charter necessary to exercise eminent domain or secure municipal bonds, and, most important, lacked the experience, to say nothing of the technocratic know-how, to see major projects to fruition. Inexperienced and ill equipped to mount massive infrastructural and commercial initiatives, Angelenos working on both public and private ventures found frustration and often failure. In early 1858, after a series of new water initiatives had left the city treasury as bare as Mother Hubbard’s cupboard, a large group of citizens petitioned for a full investigation into the city’s finances. The council first established a special committee “to examine the books of the Mayor and report the apparent amount of Revenue received from different sources, and how disposed of,” then passed the proverbial buck, demanding that the mayor “make the desired statement” and publish it in both the Star (in English) and El Clamor Público (in Spanish) at “an early date.”59 The reported deficit of a few thousand dollars alarmed the citizens, but it paled in comparison to the financial straits in which the municipality found itself the following year. Project costs exceeded planned budgets, and damage payments demanded by property holders defied all expectations. On February 21, 1859, the council endured a long meeting during which the members spent a great deal of time sifting through outstanding debts for work already completed. Although already out of money, officials nevertheless pushed forward with several new projects. Councilmen formed one committee to figure out how to pay for a mayoral-initiated evening watch and another to “fill up” Los Angeles Street and Calle de los Negros to their “established grade,” arrange new drainage for the Plaza, and “to contract for repairs upon Aliso Street.”60 By April financial reality had set in. The council began to pay less than it had agreed for some work and settled with other creditors by equalizing accounts due against taxes owed to the treasury.61

Beginning to drown in a sea of debt accrued in the name of infrastructural improvement, the council boldly asked the state legislature to authorize “the Corporation of the City of Los Angeles to borrow for twenty years the sum of Two Hundred Thousand dollars, ($200,000) to be laid out and expended upon Municipal Improvements.”62 Realizing the severity of its financial predicament, especially in light of the tremendously energetic agenda it had pursued regarding improvements to city streets and the water supply, the council charted an unprecedented course. Previously, all projects had been engaged piecemeal. Even when undertaking substantive improvements, such as rerouting the Zanja Madre, the city relied on special assessments of specie or labor. In comparison to the city’s normal budget, the price tag was nothing short of staggering. The municipality rarely took in or paid out more than $10,000 in any single year, and the treasury rarely ran above $3,000 at any given moment. Suddenly, the council adopted a different set of principles, as a loan of such size required coordinated long-term plans for putting the money to work, managing the debt, and finding new revenue sources for its repayment. To be sure, the town had grown rapidly from about 1,600 people in 1850 to nearly 4,000 in 1859 and looked poised for further growth. Nevertheless, the $200,000 request remains startling, coming as it did on the heels of widespread financial distress caused by the panic of 1857 and because it would leave the city to manage twenty times more money than it had ever controlled previously. Whether or not the city could effectively use the money to reshape spatial arrangements remained an open question.

The legislature granted the city’s request in April 1859. When the funds came, the municipal government embarked on still more ambitious street projects and yet another major water project. Only one year after building a new dam across the river, changing the costs and times of irrigation, and reorienting the Zanja Madre, the city appointed a new blue-ribbon commission to study the municipal water supply. On August 15, 1859, the members recommended a five-pronged plan carrying a total price tag of $70,000. Building a new dam across the river and an adjacent reservoir lay at the project’s “foundation.” With the new dam and reservoir, water could be stored each night instead of passing through the zanjas unused because no one irrigated after dark. The increased capacity in turn required the construction of several new flumes and a comprehensive effort to widen every principal zanja. The committee further proposed a second dam and ditch network to provide irrigation waters to those living east of the Los Angeles River. Completing its omnibus recommendations, the committee suggested expanding Dryden’s waterworks into a comprehensive system for potable water distribution.63 By 1860 the contracts had been bid out and work had begun, although the project ran over budget in almost all areas.

As a blueprint for a substantive infrastructural undertaking that required extensive planning, the committee’s report offers an excellent window into the civic ideals of its authors and of the city officers who selected the team and accepted its recommendations. The committee consisted of John Griffin, Damien Marchessault, David Porter, Abel Stearns, William Wolfskill, and Jonathan Temple, all of whom engaged in commercial rather than agricultural pursuits as their core economic endeavors. Stearns, Wolfskill, and Temple had lived in Los Angeles since the Mexican period and had married into prominent Mexican Californian families. Although earlier committees with similar mandates almost always included Mexican Californians, no members of the 1859 blue-ribbon committee claimed Mexican birth or descent.64 While the report’s technical details leaned heavily on studies and surveys conducted by two “experts” (George W. Gift, an engineer, and Captain William Johnson, surveyor for the U.S. Coast Survey), the authors waxed romantic about the power of enterprise and city government.

To the dam, “that simple bank of earth and wood,” they granted the power to “add to the beauty and wealth of our city an hundred fold” because it represented “the magic touch of improvement and enterprise” needed to push Los Angeles “to the very pinnacle of agricultural greatness.” They encouraged the council to extend its “web of irrigating ditches—streams of silver,” arguing that if agriculture thrived then “all other branches will advance hand in hand.” Increased agricultural output—“the true source of a nation’s wealth”—would “multiply employment for the laborer, the mechanic, the merchant and the professional man.” But these benefits were not ends in themselves; profits hung in the balance. “Each new acre of land that is brought under the husbandman’s skill,” they gushed, “causes hammers to ring, and the merry hum of business to be heard.” Beyond profits, those championing the new irrigation project would become rich in civic virtue. Noting that “he is a public benefactor who causes a single spear of grass to grow or a tree to thrive,” the committee asked “how much greater benefactors will be they who shall cause our vast arid plains to thrive and blossom, and yield rich returns to honest labor?” Nothing exceeded the importance of moving the new project forward, for “upon this thread hangs the welfare of our city.”65

In these flights of fancy, the committee members revealed their civic ideals. Remaking the city’s infrastructure in order to establish a foundation upon which business could thrive, they argued, was nothing less than the council members’ civic duty. Written by private citizens and presented in public to the Common Council, the report freezes for a moment the dynamic evolution of civic ideals during the late 1850s. At one level, distributing the waters of the Los Angeles River to the maximum possible number of irrigators remained paramount, preserving the city government’s original and fundamental obligation. Even as civic ideals brought to Los Angeles by newcomers from the United States and Europe during the 1850s mingled with those rooted in Spain and Mexico, irrigation remained important for its own sake: to water the fields of the city’s farmers in order to produce agricultural and ranching products for use and consumption. In the 1859 proposal, however, the underlying ethos for supporting irrigation and agriculture had changed. The report’s authors understood both water and agricultural output as commodities that, as engines of the “merry hum of business,” would determine the city’s future. By endorsing the new waterworks on such grounds, the city continued its evolution away from what historian Donald Worster characterized as the “Agrarian State” and toward the “Capitalist State.”66 Perhaps, in this context, it makes sense that no Mexican Californian served on the committee. While possessing reliable experience solving small problems in concert with older traditions, their expertise in such matters would have been relatively worthless among a group trying to repaint a big picture guided by new ideas.

The reconceptualization of water and agricultural produce as commodities wasn’t the only new idea built into the new water system. Beyond its soaring rhetoric extolling the “magic touch of … enterprise,” the committee’s report sharply criticized the water distribution system it hoped to replace. The authors lamented the “present waste” in irrigation, judged the existing zanjas “hardly adequate to the service required of them,” and warned that failing to undertake the recommended work would “stagnate improvement, cause business to halt, and trade to diminish.”67 In short, the committee argued that the existing system had to be replaced because its inefficiencies and inadequacies imperiled the city’s long-term economic survival, to say nothing of its inability to deliver “clean” and “pure” water to individual residents and businesses. The committee’s urgent appeal to the council to replace the existing infrastructure reinforced the sense that the space itself was the object of change.

As Henri Lefebvre has argued, new relationships of production are always negotiated within and inscribed upon space in specific, complementary ways. Although such relationships hadn’t yet undergone a fundamental change in Los Angeles, the civic ideals guiding public policy and the distribution of municipal water had changed enough to affect public and private spaces. The city built two new dams, dozens of new canals, wider supply zanjas, and a network of overhead pipes for domestic distribution. This work in turn led to a significant change in the internal arrangement of every public and private building receiving the domestic supply, which had to be reconfigured with pipes and faucets in order to receive and make use of these newly available waters. Moreover, Lefebvre argues, “ideology only achieves consistency” when new spaces allow it to take on “body therein.”68 In the case of the new water project, the ideology of its iteration—combining Mexican and Spanish ideas privileging irrigation with U.S. notions regarding the city’s obligation to spur “the merry hum of business”—became embodied in the form of the new dams, flumes, pipes, and water taps.

The long effort to create a separate supply of domestic water, initiated privately by Dryden, Eaton, and others and then taken up in partnership with the city, similarly demonstrates the slippage between civic ideals, infrastructural improvement, and racializing discourses. Every effort to establish, and later improve, a dedicated network of pipes to distribute water emphasized cleanliness, purity, efficiency, and progress in comparison to its allegedly dirty, wasteful, and regressive predecessors. Moreover, a seemingly invisible line connected those shortcomings to the network’s Mexican origins. In emphasizing the potential cleanliness of the water to be provided by these new projects, their advocates cast the existing system as both substandard and dirty. If Mexican Californians agreed in principle, they never initiated similar proposals, spoke out in the public press, or submitted supporting petitions. To the contrary, their previous objections to similar but less ambitious schemes, as policy makers and petitioners, indicate that they found the system good enough—surely in need of strict regulation but not requiring replacement.

Nevertheless, William Dryden, by 1860 in partnership with the city to complete the domestic conveyance network, had built a pump-driven collection tank and central distribution pipes in the middle of the Plaza (figure 4.5). In Los Angeles’s most solidly Mexican Californian space appeared an indisputable harbinger of fundamental change. Laid out at the town’s founding and serving both formally and informally to anchor the community socially and spatially, the Plaza suddenly housed a prominent monument to new civic ideals privileging commoditization, commerce, cleanliness, and profits, the very existence of which generated and nurtured further contest between immigrants from the United States and Mexican Californians.

However subtly, the entire matter of a new system of water conveyance and distribution thus introduced a potentially corrosive contrast between the new, pure, and enterprising waterworks and its old, impure, and wasteful predecessor. When coded onto their respective “American” and “Mexican” origins, a link emerges between the old system’s shortcomings and its Spanish and Mexican roots. Only by replacing the dirty, inadequate, and Mexican water network with something clean, efficient, and American could the city’s infrastructure support a bright future for Angelenos. The dirty/failing/Mexican versus pure/promising/American notion, already laden with social tension, further fused with the emerging ethos of commodities and business. Together they formed a new civic ideal, which in turn became built into the city’s physical landscape. Taking on physical form with each completed component, the new waterworks converted ideas coded to ethnoracial origins, notions previously written on paper and spoken on lips, into physical markers of difference embedded within the city’s earthen, wooden, brick, and pipe infrastructure.

Figure 4.5. View of the Plaza, looking eastward over the rear of the church from Fort Hill. Dryden’s water pump is prominent in the center of the Plaza. The Lugo Adobe, the white building with two-story columns and three dormer windows, is just beyond it. (This item is reproduced by permission of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, photCL 188 [02465])

Water-related initiatives offer only one locus of evidence suggesting the municipality’s move away from more evenly intercultural civic ideals and toward those privileging commodities and commerce. Concomitantly, the municipal government turned the lion’s share of its attention toward European Americans. The vast majority of both publicly and privately initiated action regarding the municipal waters and city streets emanated from European Americans and focused, geographically, on areas southwest of Plaza. Almost none of the boom in new street and water projects centered on the areas northwest and northeast of the Plaza, where more than half of Mexican Californian and Mexican American Angelenos lived. Although Mexican Californian residents demonstrated their continued sense of political standing by frequently petitioning the Common Council, they usually opposed new projects regarding streets and watercourses. Few petitions bearing signatures from Spanish-surnamed citizens supported or instigated new infrastructural initiatives. Mexican Californians’ participation in city government also waned; they won only four total seats on the Common Council between 1857 and 1860. Without question, the Democratic Party’s dominance and its increasingly overt racism at both the national and local levels played a role in this trend. Moreover, few Americans belonging to mixed families or experienced at maintaining intercultural civic ideals held office during these years. Such changes to broad-based participation in civic government suggest further consequences of the evolution of local civic ideals.

Rather than resisting commercial and spatial pressures, the city government first found ways to mediate compromises, then became an active partner in altering the tone of local politics, the balance of civic ideals, and the city’s spatial and commercial relationships. Without opening an explicitly public debate about the social and cultural consequences of these changes, municipal officers and their private partners began moving away from use-based principles and toward profit-oriented commercial practices. By modifying the city’s streets and reallocating its water, the city government offered public support for new economic modalities that conceived of water and agricultural produce as commodities rather than resources carrying their own intrinsic value. The city further offered official sanction to the notion that the Mexican Californian and intercultural infrastructure could not support commercial objectives.

Although civic ideals guiding municipal government began to change rapidly, city officers did not effect a parallel refashioning of the municipal apparatus. Consequently, the city and its private partners found themselves trying produce a new kind of space without the tools necessary to succeed. Even the radical infusion of $200,000 wasn’t sufficient to remake the city’s infrastructure. Building the new waterworks proved technically challenging, and the costs consistently and significantly overran the already ambitious budget. When spring arrived in 1860, many of the new and newly widened zanjas could not deliver needed water to farmers. Rendering them “serviceable” required the oversight committee to hire extra workers, “thereby contracting certain liabilities to no inconsiderable amount.” Committee chairman and former mayor John G. Nichols recommended “further improvements” to a still incomplete zanja in August 1860 because it “in a great measure fail[ed] to furnish a supply of water adequate to the necessities of those interested.”69 Within two years, the total cost for the new waterworks had risen nearly 30 percent, from the initial budget of $70,000 to $89,000.70

Private parties found equal difficulty bringing new systems to fruition while avoiding financial ruin, especially because the state didn’t offer them the same safety net for deficit spending. Despite struggling to build its own high-quality waterways at a reasonable price, the Common Council had no patience for private citizens’ similar failures. In February 1860, several citizens threatened to sue not only the Sainsevain brothers for having built a flume so badly it caused them severe losses but also the city itself, “said flume having been constructed by permission” of the council. The council took the liability threat seriously, castigated the Sainsevain brothers, and demanded that they speedily make repairs. The Water Committee subsequently deemed the renovations poorly executed and required the brothers to completely “reconstruct said flume in strict accordance” with the earlier agreement.71