1. The First Los Angeles City and County Directory, 1872 (Los Angeles: Ward Ritchie, 1963); 5, 9; Harris Newmark, Sixty Years in Southern California, 1853–1913 (Los Angeles: Dawson’s Book Shop, 1984), 72.

2. Los Angeles City Directory, 1872, 5; Los Angeles Directory Company, Los Angeles City Directory, 1875 (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Directory Company, 1875).

3. W. W. Robinson, Los Angeles from the Days of the Pueblo (San Francisco: California Historical Society, 1959), 70.

4. Los Angeles Daily News, June 20, 1870.

5. James M. Guinn, Historical and Biographical Record of Southern California (Chicago: Chapman, 1902), 1187.

6. For an innovative and balanced treatment of Pico’s political and economic life, see Carlos Manuel Salomon, Pío Pico: The Last Governor of Mexican California (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010).

7. Robinson, From the Days, 69–73.

8. Rather than suggesting Pico had to turn to capitalism, the argument highlights Pico’s understanding and desire to succeed in the economy.

9. The estimable urban historian Sam Bass Warner, Jr., argued that the “arrangement of streets and buildings” at a given moment “represent[s] a temporary compromise among such diverse and often conflicting elements as aspirations for business and home life, the conditions of trade, the supply of labor, and the ability to remake what came before.” Sam Bass Warner, Jr., Streetcar Suburbs: The Process of Growth in Boston, 1870–1900 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1962), 15.

10. Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (Cambridge: Blackwell, 1991), 10. Lefebvre also asks, rhetorically, “What is an ideology without a space to which it refers, a space which it describes, whose vocabulary and links it makes use of, and whose code it embodies?” (43).

11. Warner, Streetcar Suburbs, 20–21.

12. Richard Griswold del Castillo, The Los Angeles Barrio, 1850–1890 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), 141, 149. By the end of the 1870s, 52 percent of Mexican Angelenos lived in this ten-block-square area.

13. The 1872 city directory listed one Felis Burdell at 12 Bath Street and his occupation as hostler. Felis Gallardo, owner of the Zaragosa Restaurant at 36 Main Street, opposite El Palacio, and the widow Francisca de Martinez lived at 12 Bath Street during the 1870s. By 1880, Francisco Martinez, possibly Francisca de Martinez’s son, appeared in the city directory at 12 Bath Street as “proprietor of lodging house.” Los Angeles City Directory, 1872, 5, 2; Los Angeles City Directory, 1875; Aaron Smith, Los Angeles City Directory, 1878 (Los Angeles: Mirror, 1878); Howard L. Morris, The Los Angeles City Directory for 1879–1880 (Los Angeles: Morris and Wright, 1879).

14. Newmark, Sixty Years, 510–11.

15. María Raquél Casas, Married to a Daughter of the Land: Spanish-Mexican Women and Interethnic Marriage in California, 1820–1880 (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2007), 153.

16. Lawrence Edward Guillow, “The Origins of Race Relations in Los Angeles, 1820–1880: A Multi-Ethnic Study” (Ph.D. diss., Arizona State University, 1996), 217.

17. Office of the Census, Ninth Census (1870).

18. The cramped quarters held 61 residential units, but the increase in population meant that the average number of people living in each household unit in the Chinese district increased from 2.3 in 1870 to 4.6 in 1880. Data derived from the manuscript rolls of the Tenth Census (1880). Office of the Census, Tenth Census (1880). See also Raymond Lou, “The Chinese American Community in Los Angeles, 1870–1900: A Case of Resistance, Organization, and Participation” (Ph.D. diss., University of California, Irvine, 1982), 39.

19. Office of the Census, Tenth (1880) and Eleventh (1890) Censuses. Unfortunately, the manuscript records for the Eleventh Census (1890) burned in a fire, making detailed analysis impossible. City directories offer scant help as the majority of Chinese residents are not listed. Lacking these materials, the analysis for the period between 1880 and 1890 draws on the compendium census data, information gleaned from local papers, and the few existing secondary sources.

20. Sensational reports emphasizing the crowded and dirty nature of the Chinese district appeared regularly during the 1870s and 1880s. These stories, which claimed that as many as forty Chinese men shared sleeping halls measuring twenty-four feet by nine feet, always angled toward demonizing Chinese Angelenos and rallying support for Chinese exclusion. See for example Los Angeles Times, April 14, 1882.

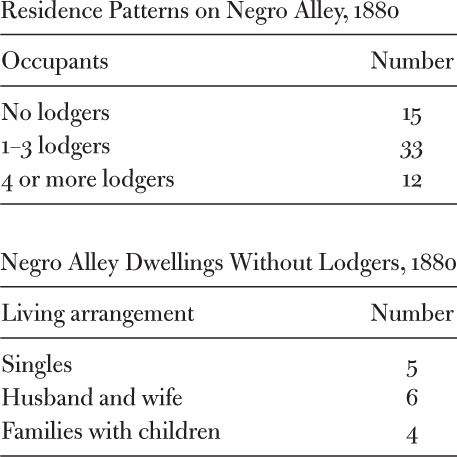

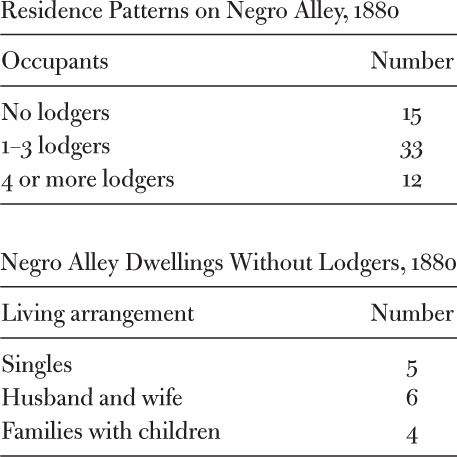

21. Census Office, Tenth Census, 1880; manuscript census of California, 1880, roll 67, pp. 12–17. The 1880 census for Los Angeles lists the names of the street in the left margin. The 1870 census does not provide street information and is consequently less useful in determining the demographics of Negro Alley. I built the following tables from the manuscript census records from 1880.

22. Although the number of couples and families is higher than the historiographical canon on Chinese immigration would predict, they were few compared to the relative total. Most Chinese nuclear families, however, lived away from Negro Alley. The 1880 census reports ninety-two Chinese families, of which only ten dwelled in the core residential district. Consequently, although one-third of all Los Angeles Chinese lived on Negro Alley, only one-ninth of nuclear Chinese families lived there. The data suggests a relationship between class and family. Perhaps those Chinese able to immigrate as intact families or those able to marry once in the United States possessed the economic resources to live elsewhere in Los Angeles.

23. Los Angeles City Directory, 1875; Robinson, From the Days, 70. Entries in the 1875 directory contain both addresses and occupations and indicate whether the address listed corresponds to a business or private residence.

24. Robinson, From the Days, 70; Los Angeles Daily News, May 25, 1870.

25. Robinson, From the Days, 71–73.

26. Newmark, Sixty Years, 186.

27. Sue Wolfer Earnest, “An Historical Study of the Growth of the Theatre in Southern California, 1848–1894” (Ph.D. diss., University of Southern California, 1947), 374. Interculturally experienced Angelenos Pico, Sepúlveda, and John Downey formed the committee that planned the opening ball.

28. My analysis here follows that offered by Casas, Married to a Daughter of the Land, 148. Although Casas does not discuss Doña Abbott or the Merced Theatre, she argues that “Californianas were aware of the ‘middle ground’ on which they stood” and that in the face of increasingly active efforts to differentially racialize European and Mexican Americans they “nevertheless still actively negotiated, protected, and maintained their social, cultural, and racial privileges for themselves and for their children.”

29. Earnest, “Growth of the Theatre,” 375. Harris Newmark kept one of the bills printed in Spanish, and remarked, “Plays were often advertised in Spanish.” Newmark, Sixty Years, 422. The placard read, “Teatro Merced/Los Angeles/Lunes, Enero 30 de 1871: Primero funcíon de la Gran Empresario Veterano de San Francisco, Veinte y Cuatro Artistas de ambos sexos, todos conocidos como estrellas de primera clase.”

30. Los Angeles Daily Star, July 1, 1871. The Star gave the show a generally favorable review.

31. Earnest, “Growth of the Theatre,” 374–75. For a similar argument regarding the ways that minstrel shows helped bind racially ambiguous Irish Americans to white identity, see David Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness (London: Verso, 1991).

32. Los Angeles City Directory, 1875; Lou, “Chinese American Community,” 202–25. European Americans also owned gambling houses throughout the city.

33. Los Angeles Times, June 13, 1887, reported finding no fewer than “50 to 100 white people wandering around that sweet-scented neighborhood on any given night.”

34. Raymond Lou described Fan Tan as “a game of chance in which the players bet on the numbers, from one to four, of buttons (or any like object) remaining from a random quantity that the dealer had placed beneath a cup or bowl and counted out in groups of four. The last group of buttons determines the winner. Players also have the option of betting odd or even.” For those who wanted to gamble but were unwilling to interact so intimately with others, the Chinese lottery offered more casual access, yet tickets were available only at certain gaming houses and Chinese-operated businesses around town. Even the most hesitant players had to purchase their tickets and redeem their winnings through face-to-face interaction with Chinese residents. Interestingly, lottery games had both recreational and economic components. Lou, “Chinese American Community,” 206–7.

35. Los Angeles City Directory, 1872, 28–31.

36. Castillo, The Los Angeles Barrio, 134–38.

37. Los Angeles City Directory 1872, 28–29. The directory did not list the F. & A.M.’s meeting times.

38. Ibid., 30.

39. Los Angeles City Directory 1875, 88–94; Smith, 1878 City Directory, 6–8; Morris, Los Angeles City Directory, 1879–1880, 26–30. Neither the 1878 nor the 1879–80 directory provides membership data.

40. Castillo, The Los Angeles Barrio, 134–38. New groups such as Los Caballeros de Trabajo, an organization of workers dedicated to labor concerns; El Corte de Colón, a fraternal organization; and political clubs like the Spanish-American Republican Club (conservative) and La Sociedad Progresista Mexicana (progressive) joined older organizations, for example, Los Hijos de Temperencia (a temperance society) and Los Lanceros de Los Angeles (a militia company founded by Juan Sepúlveda). Other new societies included La Companía de Rifleros, La Junta Guardía Hidalgo, and Las Reformistas.

41. Lou, “Chinese American Community,” 25–57.

42. Nevertheless, the boundary between public, communally oriented huiguan and the more criminal tongs remained blurry, making it important to avoid romanticizing the huiguan and their impact on the community. Competition for work contracts, commercial power, or ownership of particular women occasionally provoked internecine violence, which created negative public opinion and, at times, imperiled the entire community. Too often, however, this is the only aspect of tongs presented in the literature, and their genuinely productive role in community life is ignored. See Scott Zesch, “Chinese Los Angeles in 1870–1871: The Making of a Massacre,” Southern California Quarterly 90:2 (Summer 2008): 109–58, 115–17, and 119–23.

43. John T. McGreevy, Parish Boundaries: The Catholic Encounter with Race in the Twentieth-Century Urban North (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 28.

44. La Crónica, September 18, 1878. The paper reported that every group and political party had representatives in the parade, and many more participated in the larger festivities, which included public speeches and a full-blown fiesta with food, music, and dancing.

45. Leonard Pitt, The Decline of the Californios: A Social History of the Spanish-Speaking Californians, 1846–1890 (Berkeley, 1971), 263. One of the floats carried the town’s “founding fathers”: two Indian women who claimed to be 102 and 117 years old, respectively.

46. Pitt, Decline of the Californios, 266–67.

47. A story relating the Festival of the Moon can be found in Los Angeles Times, August 27, 1882, and a report on a ceremony commemorating ancestors staged by the Chinese Masonic fraternity appeared on September 7, 1882. The “elaborate ceremonies” relating to a funeral are described in detail in Los Angeles Times, October 9, 1885.

48. Los Angeles Times, October 25, 1884. The Times described Tsooi as a “Chinese priest” and “great religious teacher” who “lived in China three thousand years ago.” The description of this triennial event demonstrates some of the characteristic ambiguity expressed by whites toward Chinese Angelenos. Although summoning numerous anti-Chinese stereotypes, calling them heathens and sarcastically referring to their use of opium, the article also called Chinese “religious heathens” and took Tsooi’s religiosity and works seriously.

49. Los Angeles Times. Primers appeared October 13 and 22, and coverage ran October 23–25, 1887. Despite the aesthetic praise and a genuine effort to discuss the celebration objectively, the Times still savaged Chinese participants, especially “the average Chinaman,” who “would probably be found to be in a condition … similar to the American youth could he have two Fourths of July together and a Christmas following.” To wit, “he is about to celebrate something about which he cares little and knows less, which comes around once in three years, and has a significance perhaps to Chinese of education, but to ‘John’ is a three day’s lay-off and a good time generally.” Los Angeles Times, October 22, 1887.

50. Los Angeles Times, February 4, 1886, and February 5, 1886.

51. Richard Griswold del Castillo’s work with Spanish-language newspapers during the period supports this argument. “The increasing use of ‘La Raza’ as a generic term in the Spanish-language press,” Castillo writes, “was evidence of a new kind of ethnic consciousness.” Additionally, Castillo argues that “La Raza emerged as the single most important symbol of ethnic pride and identification,” noting it was frequently used in opposition to “Anglo-Sajones” or “norteamericanos.” His data come from a number of different, and differently oriented, newspapers and the references he cites occur over time from the 1850s to the 1890s. Castillo, Los Angeles Barrio, 133–34, and nn79–83.

52. Intertwined lives across ethnoracial boundaries continued into the twentieth century, as demonstrated by Mark Wild in Street Meeting: Multiethnic Neighborhoods in Early Twentieth Century Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

53. David Delaney, Race, Place, and the Law, 1836–1948 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998), 7.

54. Pitt, Decline of the Californios, 249; William Deverell, Railroad Crossing: Californians and the Railroad, 1850–1910 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996).

55. Los Angeles Star, December 12, 1872.

56. LACA, April 4, 1873, Council Minutes, vol. 10, 269–73.

57. LACA, May 3, 1873, Council Minutes, vol. 10, 279.

58. David Delaney, a historical geographer, has suggested that spatial organization in society is key because “the world of everyday life is carved up into meaningful spaces” that “contain culturally specific codes which condition basic experiences of access, exclusion, and protection.” These codes have tremendous power, Delaney argues, because “call[ing] to mind the experience of access granted or denied, of exclusions and expulsions enforced, of protection or sanctuary respected or violated, is to become conscious of the social relations of power.” Delaney, Race, Place, and the Law, 4–5. Writing about New York, Matthew Gandy theorizes that putting questions of environmental justice at the center of analysis “compels us to see urban environmental change not simply as a function of technological change or of the dynamics of economic growth but as an outcome of often sharply different sets of political and economic interests.” Matthew Gandy, Concrete and Clay: Reworking Nature in New York City (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002), 4.

59. City of Los Angeles, “Zanjero’s Report, 1883,” Los Angeles Municipal Reports, 1879–1896, 115.

60. It is important to note, however, that the city retained control of this water despite the changes. The fees applied not only to those living within the city, but those outside the limits also had to pay for use of the water. From this perspective, the city exercised its claim to the corpus of the water in the river.

61. LACA, May 3, 1873, “An ordinance to provide for the … management and control of the Zanjas and irrigating ditches in the city of Los Angeles and to regulate the prices and the equitable distribution of water flowing therein” Council Minutes, vol. 10, 292–95. The ordinance ordered the zanjero “to divide the city in the best and most convenient manner into three irrigating districts,” with an individual deputy for each. These deputy zanjeros directed water from the main zanjas through access gates at each landholder’s property according to his or her purchases. For twelve hours of daytime flow, the city charged $1.75, for nighttime, $1.00, and a combined $2.75 for twenty-four hours of access. Those living outside the city limits but drawing water from the river paid premium rates of $3.00 during the day, $2.00 at night, and $5.00 for a full twenty-four-hour cycle. Moreover, the ordinance made it illegal to receive water without payment and, under threat of arrest, made it illegal for any person to remove water directly from the principal zanjas.

62. Although the idea of pueblo rights remained operational in a legal sense, it did so under a new set of rules that privileged hygiene and revenue over communal use, changing the meaning of pueblo rights on the ground. See chapter 5.

63. LACA, April 4, 1873, Council Minutes, vol. 10, 269–73.

64. Robert M. Fogelson, The Fragmented Metropolis: Los Angeles, 1850–1930 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1967), 26.

65. Los Angeles Evening Express, April 20, 1877.

66. City of Los Angeles, Revised Charter and Compiled Ordinances of the City of Los Angeles, compiled by William M. Caswell (Los Angeles: City Publication, 1878), 425–29.

67. Castillo, Los Angeles Barrio, 139–50, map at 147.

68. In an act amending the city charter, the California State Legislature granted Los Angeles both the power of eminent domain and the right to impose special assessments “upon the petition of a majority of the owners of real estate fronting upon any street or avenue of said city, or upon a vote of two thirds of the Common Council.” Consequently, the city could impose its will on owners even if they had not petitioned the council for a project. For the amendment’s full text, see LACA, February 20, 1872, untitled records, box b-0094, vol. 7, 476.

69. LACA, July 3, 1887, Council Minutes, vol. 23, 231. By 1887 the city clerk filled in the details of individual sewer ordinances on a form that already contained the cited language. Sewers like these came into being after enough landowners along the proposed line signed a petition to the city. Such projects became frequent by the late 1880s. On July 3, 1887, the council authorized ten other sewers, all laid out on preprinted forms. If owners accounting for “two-thirds of the frontage thereof” filed a “written remonstrance against said improvement, the same [would] not be further proceeded in or made.”

70. Drawing from my own analysis of the 1880 census, only fifteen of sixty-one households in Chinatown’s most crowded block were without lodgers. Of these, it is doubtful that more than a handful actually owned their homes. Census Office, Tenth Census, manuscript census of California, 1880, roll 67, 12–17. In Sonoratown, according to Castillo, only about 10 percent of the district’s 1,000 residents owned real estate. Castillo, Los Angeles Barrio, 141–50.

71. See, for example, LACA, April 4, 1873, Council Minutes, vol. 10, 272. For a substantive discussion of socioeconomic elements of the location of the first sewers, which crossed through the lands of several long-tenured Angelenos, see David Torres-Rouff, “Water Use, Ethnic Conflict, and Infrastructure in Nineteenth Century Los Angeles,” Pacific Historical Review 75:1 (February 2006): 119–40.

72. LACA, May 16, 1873, Council Minutes, vol. 10, 304. The city further charged the surveyor and the street superintendent to submit a list of all delinquent owners to the city attorney, who made a second effort to collect, after which he placed liens against the property of owners still shirking. LACA, May 23, 1873, Council Minutes, vol. 10, 299–300.

73. “Report of Fred Eaton, City Surveyor, May 3, 1887,” and “Report of Rudolph Herring, Consulting Engineer, September 6, 1887,” Department of Sewage Design, City Hall, Los Angeles; Los Angeles Herald, August 31, 1892; Fogelson, Fragmented Metropolis, 32–34.

74. In his 1893 annual report, the city engineer noted that only 965 feet of sewer had been laid using the bonds, at a cost of only $7,752. Considering that the total amount of bonds authorized exceeded a million dollars, the city made little effort to put the bond funds to immediate use. City of Los Angeles, “City Engineer’s Report, 1893,” Los Angeles Municipal Reports, 1879–1896, 34.

75. City of Los Angeles, “Sewer Committee’s Report, 1884,” Los Angeles Municipal Reports, 1879–1896, 106.

76. Writing about New York, but thinking more broadly about urban infrastructure during this period, Matthew Gandy suggests, “The modernization of nineteenth-century cities in Europe and North America was not carried out in order to improve the conditions of the poor but to enhance the economic efficiency of urban space for capital investment.” This argument fits well within the umbrella framework I sketch regarding the transition in Los Angeles from the agrarian to the capitalist state. In this framework, the absence of sewers in Sonoratown and Chinatown would derive from those areas not being part of this larger economic plan. Further, Gandy argues, “In this sense, the scale of new public works and the pace of technological change masked the persistence of [extant] social and political inequalities.” Gandy, Concrete and Clay, 37.

77. During a similar phase in Manhattan’s development, the city government argued that “an attractive city was an orderly city” and commissioned a map subjecting all of Manhattan to a grid, which became a blueprint for all future growth. Although many private holders objected to the changes made to their streets (and to Manhattan as a whole by essentially leveling all topography in making a flat surface), this opposition faded when property holders, real estate developers, and investors realized that conformity to the plan made all growth predictable and therefore quite profitable. Historian Hendrik Hartog concludes that this plan “transformed space into public philosophy,” one that specifically embodied growth, regularity, and predictability. Hendrik Hartog, Public Property and Private Power: The Corporation of the City of New York in American Law, 1730–1870 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983), 158–63, quotes on 159 and 163.

78. See, for example, Los Angeles Star, December 12, 1872.

79. In addition to the discussion below, see Fogelson, Fragmented Metropolis, 24–42.

80. LACA, February 28, 1872, Council Minutes, vol. 7, 476. The city gained this muscle when the California State Assembly altered the city’s charter and granted it the “power, upon the petition of a majority of the owners of real estate fronting upon any street or avenue of said city, or upon a vote of two thirds of the Common Council of said city to open, widen, improve, grade or cause to be improved or graded, such streets or parts of streets, or avenues, and to make repairs or improve the sidewalks and crosswalks of said streets, by grading, paving, or planking such streets, sidewalks and crosswalks … at the cost and expense of all such owners of real estate in proportion to the number of feet fronting on such street or part of street owned by each one… and for all such costs and expenses, the contractors under the city and the city shall have a lien upon the real estate so fronting upon said streets and shall have power by ordinance to prescribe the mode and manner of collecting the same.”

81. This idea has reached its fullest expression in Gianfranco Poggi, The Development of the Modern State: A Sociological Introduction (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1978), and Poggi, The State: Its Nature, Development, and Prospects (Cambridge: Polity, 1990).

82. In particular, Isaias Hellman and Hellman, Hass, and Company, which owned key buildings along the line, gave the city fits. In 1875 their tactics led the city to abandon its first effort to extend Los Angeles Street. Starting in 1877, city leaders decided to expropriate property valued at $50,000 and subsequently spent two more years lobbying the state legislature for permission to sell bonds sufficient to generate the necessary cash. Just as the printed bonds arrived at the municipality—approved and ready for sale—the state supreme court granted the property owners an injunction, leading the matter to be dropped entirely. Hellman, Haas, and others repeatedly thwarted the city thereafter by agreeing to let work begin and then demanding a reappraisal of their property and a renegotiation of the terms just as work was to have commenced (see, for example, Los Angeles Times, August 22, 1882). Still hopeful but hardly optimistic that it could get the owners along the proposed new route of Los Angeles Street to yield, the Common Council reopened negotiations to clear Negro Alley beginning in March 1882. The Times touted the 1882 effort to eradicate Chinatown, then lamented another failure. Linking racial hostility to commercial and booster aspirations, the Times argued that the failure to open Los Angeles Street impeded development. Moreover, the Chinese who lived there lessened the city’s appeal to outsiders even though “any intelligent mind” would recognize “that the enhanced value” of their property “would more than compensate the owners for their temporary loss.” Los Angeles Times, April 8, 1882.

83. Even changing the name proved challenging. The resolution’s text, as logged into the City Council minutes, provides some insight as to the challenge at hand. On the original ordinance, the secretary first wrote “Nigger Alley,” then he or someone later thought better of it, scratching out “Nigger” and replacing it with “Negro” above. LACA, March 22, 1877, Council Minutes, vol. 12, 647–49.

84. Los Angeles Times, July 24, 1887.

85. Yucheng Qin, The Diplomacy of Nationalism: The Six Companies and China’s Policy Toward Exclusion (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009), 102.

86. For the Chinese response, see Los Angeles Times, July 26 and August 3, 1887. Specifically, Chinese community leaders and business owners demanded that the city find the responsible parties, bring them to justice, and compensate the business owners for their losses. Of particular importance, the Chinatown firebugs also operated at the end of a broader statewide movement by anti-Chinese activists to set fire to Chinese districts. As a result of the wave of fires, every insurance company had cancelled policies that covered Chinese residences and commercial operations. Consequently, Los Angeles’s Chinese had no other pathway to compensation.

87. Los Angeles Times, August 9, 1887. The lot measured nine hundred by three hundred feet, and the buildings were to face inward onto a central courtyard. Bee claimed that “the Chinamen objected to my plans at first, but I soon talked them around.” Editorials claiming the fire had created a good opportunity for the opening of the alley appeared on July 28 and August 2, 1887.

88. Los Angeles Times, August 10, 1887.

89. LACA, August 29, 1887, Council Minutes, vol. 23, 679–82; Los Angeles Times, August 30, 1887. At the council’s regular meeting of August 29, 1887, Dr. Hagan reported that everything seemed in fine shape. However, property owners in the area filed complaints with the city, and by August 19 more than 360 Angelenos had signed a petition of protest. The Board of Education issued a formal protest to the City Council on August 22, the same day on which the city attorney admonished the council that it needed to play a greater role in the process, from investigating the concerns of neighboring residents to exercising greater oversight through the offices of public works and public health. Los Angeles Times, August 16, 19, and 23, 1887; and LACA, August 22, 1887, Council Minutes, vol. 23, 673–74. Specifically, the Board of Education argued that “the presence of this obnoxious class in the neighborhood of these large and crowded schools will greatly hinder all efforts to educate these children into good citizenship by thus familiarizing them from their most tender years with degradation and vice.” LACA, August 22, 1887, Council Minutes, vol. 23, 673.

90. Los Angeles Times, September 2, 1887. One member of the crowd promised that “the advent of the Chinese in that vicinity would be marked by such an era of bloodshed and rapine that it would horrify the whole world.”

91. Los Angeles Times, January 10, 1888.

92. The City Council and interested parties apparently considered this sufficient to avoid further delay. West-side property holders agreed to the plan on December 6, and the mayor reported the imminent action to the city on December 20 as part of his annual message. Participating property interests all along Los Angeles Street were so happy they gave City Attorney Daly, who had been instrumental in moving the project forward, a gold watch as a Christmas gift. It bore the inscription “from the property-holders of Los Angeles Street, as a token of appreciation of his valuable services in securing the opening of the street.” Los Angeles Times, December 7, 1887, December 21, 1887, and December 25, 1887.

93. Work began on January 11, 1888, and seemingly caught many of the residents off guard. The surviving account of the demolition is, unfortunately, badly fragmented (Los Angeles Times, January 12, 1888), but it can be deduced that the Chinese gathered around the workmen before realizing that this time it would not be stopped, then busied themselves with packing their belongings. Although one of the property owners enjoined further work on January 19, because the city had not yet paid him as promised, work resumed shortly thereafter. Los Angeles Times, January 20, 1888.

94. For the classic scholarly treatment of the anti-Chinese movement in California, see Elmer C. Sandmeyer, The Anti-Chinese Movement in California (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991, orig. pub. 1939). Taking a more national perspective are Alexander Saxton, The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chinese Movement in California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971), and Andrew Gyory, Closing the Gate: Race, Politics, and the Chinese Exclusion Act (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

95. In March 1882, the U.S. Congress passed a bill sponsored by Senator Miller that would have excluded all Chinese immigration for twenty years and barred Chinese immigrants already living in the United States from naturalizing as citizens. President Chester Arthur enraged anti-Chinese advocates when he vetoed the act because it jeopardized diplomatic and commercial relations with China. By May the Congress passed a new bill that reduced the period to ten years and specifically excluded only “Chinese laborers,” defined to “include both skilled and unskilled workers.” Arthur signed the new bill on May 6, 1882, ushering in a new regime of immigration restriction and border control. Sandmeyer, Anti-Chinese Movement, 92–95, quote at 94.

96. Los Angeles Times, March 4, 1882; Los Angeles Star, December 12, 1872.

97. Los Angeles Times, April 8, 1882.

98. LACA, April 8, 1882, Council Minutes, vol. 15, 317–18. Los Angeles Times, April 9, 1882. Councilman Cohn, who introduced the resolution, drew on an 1880 state law titled “An Act to Provide for the Removal of Chinese Whose Presence Is Dangerous to the Well Being of Communities,” and on article 19, sec. 4 of the state constitution, which granted “municipalities the right to remove Chinese from the limits of its boundaries, or to designate certain territory within its boundaries to be occupied by Chinese.” Although municipalities throughout the West made similar efforts to legislate Chinese residents from their boundaries during this period, questions about public health had remained in the background in Los Angeles as economic concerns took center stage. For extensive and insightful examinations of the relationship between race and public health in nineteenth-century Los Angeles and San Francisco, see Natalia Molina, Fit to Be Citizens? Public Health and Race in Los Angeles, 1879–1939 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), and Nayan Shah, Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

99. A letter to the editors on April 12, 1882, not only commended Councilman Cohn but also thanked the Times, to whom the author credited with introducing the idea (a brief notice on March 17 suggested Chinatown’s condemnation). Los Angeles Times, April 12, 1882, and March 17, 1882.

100. On April 14 and 15, 1882, the Times ran two such pieces. The first reported on a police-guided tour of the Chinese district. The following day the Times reported on the visit of a doctor to the area, documenting both the poor health of one syphilitic Chinese and the crowd that gathered upon hearing a doctor was in the vicinity. Los Angeles Times, April 14, 18882, and April 15, 1882.

101. Following a journey through a “Chinese house” in an old adobe, a prostitute’s crib, and an opium den, the author decried the poor air, foul-smelling exteriors (themselves a product of the lack of sewerage), diseased call girls, and degraded dope fiends that agglomerated “here in the fairest spot on God’s footstool.” Los Angeles Times, April 14, 1882.

102. Los Angeles Times, April 22, 1882.

103. LACA, April 22, 1882, Council Minutes, vol. 15, 354. Specifically, Hazzard worried that expelling Chinese Angelenos would be “contrary to the Constitution of the United States and indirectly in conflict” with the Burlingame Treaty. Signed in Washington, D.C., in July of 1868, the Burlingame Treaty required both the United States and China to recognize “the inherent and inalienable right of man to change his home and allegiance, and also the mutual advantage of the free migration and emigration of their citizens and subjects, respectively for purposes of curiosity, of trade, or as permanent residents.” Particularly salient to Hazzard’s refusal to comply with the council’s request to draft an ordinance banishing the Chinese from the fire limits of Los Angeles, the treaty stipulated that “Chinese subjects visiting or residing in the United States, shall enjoy the same privileges, immunities, and exemptions in respect to travel or residence, as may there be enjoyed by the citizens or subjects of the most favored nation.” Sandmeyer, The Anti-Chinese Movement, 78–79. Consequently, Hazzard argued, the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution could be invoked by the federal government to overrule the city because the proposed measure targeted a single, specific group. See also Los Angeles Times, May 2, 1882.

104. Los Angeles Times, May 17, 1882, and June 7, 1882.

105. Los Angeles Times, August 19, 1882, August, 29, 1882, September 22, 1882, July 14, 1883, and July 19, 1883. Editorials on August 19, August 29, and September 22, 1882, wove together appeals to open Los Angeles Street for commercial reasons with complaints about the deleterious consequences Chinese Angelenos foisted on the city’s public health. On July 14 and 19, 1883, the paper again decried Chinatown as dirty and diseased. Amid frustration that Negro Alley’s property owners continued their resistance, the Times unleashed another series of complaints based on public health in March 1885.

106. Los Angeles Times, October 4, 1885.

107. LACA, August 29, 1887, Council Minutes, vol. 23, 679–82. The brick buildings were to be “supplied with water, gas, and a thorough sewer system.” Other amenities included water closets and porcelain sinks, a paved rear yard, and gutters connected to the sewers, convincing the city’s head public health official, Dr. Hagan there would “be no reason” why any “nuisance or filth should be maintained on the premises.”

108. For an extensive discussion of the use of public health codes to impose racially informed projects against Chinese, see Molina, Fit to Be Citizens, esp. chapter 1.

109. Los Angeles Times, June 4, 1889, and June 22, 1889.

110. Los Angeles Times, May 16, 1890.

111. As an example, Lefebvre asks what would remain of “Judaeo-Christian” ideology “if it were not based on places and their names: church, confessional, altar, sanctuary, tabernacle? What would remain of the Church if there were no churches?” He answers that Christian ideology “created the spaces which guarantee that it endures.” Lefebvre, Production of Space, 43–44.

112. Los Angeles Times, July 7, 1887.

113. Earnest, “Growth of the Theatre,” 377. Melodramas and vaudeville replaced the “respectable” companies, minstrel shows became common, and patrons could order drinks during performances.

114. Pitt, Decline of the Californios, 252–53. “The traditional rancho culture persisted” not in the core of Los Angeles but instead in the San Fernando, San Gabriel, and San Bernardino Valleys, and up the coast toward Ventura and Santa Barbara. There, important families continued to “entertain one another in round-robin fashion,” although without the “opulent form” of the fiestas of old. Nevertheless, theses events often brought more than sixty families together, many of them intercultural or bringing along European American guests.

115. Los Angeles Times, February 5, 1886.

116. Los Angeles Times, July 5, 1887. Detonating fireworks so close to the old adobes that made up Chinatown, the whole event was perhaps a ruse to burn the district (which had been unsuccessfully attempted only ten days earlier, and which would be effected only twenty days hence), but Chinese residents kept their roofs wet and protected their homes.

117. Los Angeles Times, December 8, 1881.

118. Los Angeles Times, February 5, 1886.

1. Annie Reynolds, The Education of Spanish-Speaking Children in Five Southwestern States, United States Department of the Interior Bulletin, No. 11 (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1933), 6.

2. Los Angeles Times, July 7, 1887. The sweep of time and events suggested here bears a striking resemblance to an article titled “Destiny of California” published in the Los Angeles Star on February 15, 1855, three decades earlier, and to La Fiesta’s history parade, staged seven years later.

3. Lansford Hastings, The Emigrant’s Guide to Oregon and California (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1932; orig. Cincinnati: George Conclin, 1845), 108.

4. Clarence Pullen, “Los Angeles,” Harper’s Weekly 10:18 (1890): 807.

5. Harris Newmark, Sixty Years in Southern California, 1853–1913, Containing the Reminiscences of Harris Newmark (Los Angeles: Dawson’s Book Shop, 1984), 605.

6. Seaver Center for Western History Research, 1178 OV, Max Meyberg Fiesta Scrap-book (hereafter SC, Max Meyberg Fiesta Scrapbook), second item in scrapbook, letter written by Meyberg on corporate stationery, with archivist’s pencil notation suggesting date of 1930–31. Also cited in William Deverell, Whitewashed Adobe: The Rise of Los Angeles and the Remaking of Its Mexican Past (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 54. For fuller accounts of the history of La Fiesta de Los Angeles, see Deverell, Whitewashed Adobe, chapter 2, and Deverell and Douglas Flamming, “Race, Rhetoric, and Regional Identity: Boosting Los Angeles, 1880–1930,” in Richard White and John M. Findlay, eds., Power and Place in the North American West (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999), 117–43. I am grateful to Professor Deverell for pointing me to the Max Meyberg scrapbook and for encouraging my analysis of the 1894 Fiesta.

7. SC, Max Meyberg Fiesta Scrapbook, sixth item, clipping from unnamed, undated newspaper.

8. Deverell, Whitewashed Adobe, 53–54.

9. SC, Max Meyberg Fiesta Scrapbook, second item, letter from Meyberg.

10. “Fiesta Features,” Los Angeles Times, March 28, 1894, 4; “Pleasures Rein,” Los Angeles Times, April 10, 1894, 8.

11. “Pleasures Rein,” 8.

12. “Fiesta Features,” 4.

13. “Pleasures Rein,” 8.

14. Deverell, Whitewashed Adobe, 57–58, quoting from Christina Wielus Mead, “Las Fiestas de Los Angeles: A Survey of the Yearly Celebrations, 1894–1898,” Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly 31 (June 1949): 63–113, quote at 69. Besides Chinese and Yuma Indians, the Turnverein and Maccabees marched with other organizations, and a black American group produced a float for the mercantile section, “a handsome piece” sporting “three or four appropriate banners, such as ‘United We Stand. Divided We Fall.’” “The Parade,” Los Angeles Times, April 11, 1894, 8.

15. Robert Rydell, All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876–1916 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 6, 40.

16. SC, Max Meyberg Scrapbook, clipping from Los Angeles Herald, May 18, 1894. For the role of parades in giving social order to nineteenth-century cities, see Mary Ryan, “The American Parade: Representations of Nineteenth-Century Social Order,” in Lynn Hunt, ed., The New Cultural History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 131–53.

17. Deverell, Whitewashed Adobe, 61. Deverell offers a nuanced discussion of the ways La Fiesta evinced a “contrived” social peace.

18. SC, Max Meyberg Scrapbook, “It Has Taken the Town,” undated newspaper clipping.

19. SC, Max Meyberg Scrapbook, clipping from Los Angeles Herald, May 18, 1894.

20. Deverell, Whitewashed Adobe, 68; Raymond Lou, “The Chinese American Community in Los Angeles, 1870–1900: A Case of Resistance, Organization, and Participation” (Ph.D. diss., University of California, Irvine, 1982), 238–39.