Migration in Prosperity, Depression, and War, 1921–1945

The passage of restrictive immigration legislation and the phasing in of the national origins system in the 1920s brought an entire era of American immigration history to an end. The century of immigration was over. Even more effective in curtailing immigration were the Great Depression of the 1920s and World War II. But immigration never ceased. Table 11.1 provides a year-by-year breakdown of immigration and emigration for the years 1920–45.

The nearly five million immigrants of those years are largely ignored in most histories of American immigration, yet they are an important part of the story. Although the average immigration for the quarter century was nearly two hundred thousand a year, that figure was not even approached after 1930. Nearly half (48.8 percent) of all the immigrants during the whole period entered in the four years before the 1924 act took effect. More than a third (36.7 percent) came in the following six years, while the last fifteen years of depression and war saw just over a seventh (14.5 percent). The figures are still more unbalanced if we look at net immigration—that is, immigration minus return migration. During the quarter century there was almost one remigrant for every three immigrants (32.2 percent). Of the 3.25 million net immigration more than half (53.4 percent) came during 1921–24, just over two-fifths (40.6 percent) during 1925–30, and not quite a sixteenth (6 percent) for the 1931–45 period. In fact, under the impact of the worst years of the Great Depression more persons remigrated than immigrated for four consecutive years (1932–35), and in 1936 the positive balance was a mere 516 persons. Of the million and a half remigrants, just under two-fifths (39.1 percent) left during 1921–24, about two-sevenths (28.5 percent) during 1925–30, and nearly a third (32.5 percent) during 1931–45. However, when one looks behind the mere data to the millions of individual decisions they represented, it is clear that there were several distinct kinds of population movements involved. Only by examining the three separate periods—the last years before the Immigration Act of 1924, the first “normal” six years of its operation, and the fifteen-year period of depression and war—will the varying streams and counterstreams of immigration become clear. Tables 11.2 and 11.3 show some of the major trends.

Table 11.1

Immigration and Emigration, 1921–1945

YEAR |

IMMIGRATION |

EMIGRATION |

NET IMMIGRATION |

1921 |

805,228 |

247,718 |

557,510 |

1922 |

309,556 |

198,712 |

110,844 |

1923 |

522,919 |

81,450 |

441,469 |

1924 |

706,896 |

76,789 |

630,107 |

1925 |

294,314 |

92,728 |

201,586 |

1926 |

304,488 |

76,992 |

227,496 |

1927 |

335,175 |

73,336 |

261,839 |

1928 |

307,255 |

77,457 |

229,798 |

1929 |

279,678 |

69,203 |

210,475 |

1930 |

241,700 |

50,661 |

191,039 |

1931 |

97,139 |

61,882 |

35,257 |

1932 |

35,576 |

103,295 |

-67,719 |

1933 |

23,068 |

80,081 |

-57,013 |

1934 |

29,470 |

39,771 |

-10,301 |

1935 |

34,956 |

38,834 |

-3,878 |

1936 |

36,329 |

35,817 |

512 |

1937 |

50,244 |

26,736 |

23,508 |

1938 |

67,895 |

25,210 |

42,685 |

1939 |

82,998 |

26,651 |

56,347 |

1940 |

70,756 |

21,461 |

49,295 |

1941 |

51,776 |

17,115 |

34,661 |

1942 |

28,781 |

7,363 |

21,418 |

1943 |

23,725 |

5,107 |

18,618 |

1944 |

28,551 |

5,669 |

22,882 |

1945 |

38,119 |

7,442 |

30,677 |

Total |

4,806,592 |

1,547,480 |

3,259,112 |

Average |

192,264 |

61,899 |

130,365 |

During the first of these periods, 1921–24, conflicting forces were at work. On the one hand, there was a pent-up demand of persons who had wanted to come to the United States and had been prevented by the war, plus persons, some of them refugees, whose emigration was impelled either by what had happened during the war or by postwar conditions. On the other hand, there was a similarly pent-up demand of persons who wanted to return to Europe and elsewhere. Thus the figures for 1921—unaffected by the Emergency Quota Act of 1921—are inflated. The eight hundred thousand immigrants of that year are comparable to, but not nearly as large as, the numbers coming in just before the war (in the ten years 1905–14 immigration had averaged more than a million a year), while the nearly two hundred fifty thousand returners were also about 80 percent of the prewar average. During the three years that the first quota act was in effect, gross immigration was reduced to about half of the prewar decade’s average (about half a million annually), while remigration was at about a third of the prewar level. The numbers for 1922, which saw returners almost two-thirds as numerous as immigrants, were probably affected more by the sharp postwar American depression than by the legislation. Similarly, the figures for 1924, when remigrants were only a tenth of immigrants, are probably skewed the other way by justified fears of a stricter law. However, the notion that the United States was about to be swamped by an unprecedented flood of immigrants is simply not borne out by the data. Nevertheless, the perception was otherwise. Many Americans shared the disgust of Henry James, who, visiting Ellis Island before the war, could only shudder at what he called “the visible act of ingurgitation” and wonder what it could mean to share “the sanctity of his American consciousness . . . with the inconceivable alien.”1

Table 11.2

Immigration and Emigration, by Period, 1921–1945

PERIOD |

NUMBER OF IMMIGRANTS |

NUMBER OF EMIGRANTS |

NET MIGRATION |

1921–24 |

2,344,599 |

604,699 |

1,739,930 |

Average |

586,150 |

151,168 |

439,982 |

1925–30 |

1,762,610 |

440,377 |

1,322,233 |

Average |

293,768 |

73,396 |

220,372 |

1931–45 |

699,283 |

502,434 |

196,849 |

Average |

46,619 |

33,496 |

13,123 |

Total |

4,806,492 |

1,547,480 |

3,259,012 |

Europe continued to be the chief source of immigrants, but not quite as heavily as before the war. Then Europeans were about 90 percent of all arrivals, while in the immediate postwar years they were just under two-thirds. Ironically, the nation that most benefited from the new pattern of immigration was America’s former enemy, Germany, which by 1924 was accounting for a fifth of European immigration and a tenth of the total. The prewar figures were less than 4 percent of either. Conversely, as was the intent of the lawmakers, the percentages from Eastern and Southern Europe were slashed. In 1921, the last year before the Emergency Quota Act went into effect, 95,000 Poles and 222,000 Italians came, representing about two-fifths of all entrants. In the next three years about 28,000 Poles and 46,000 Italians came annually: They were about one-seventh of all immigrants.

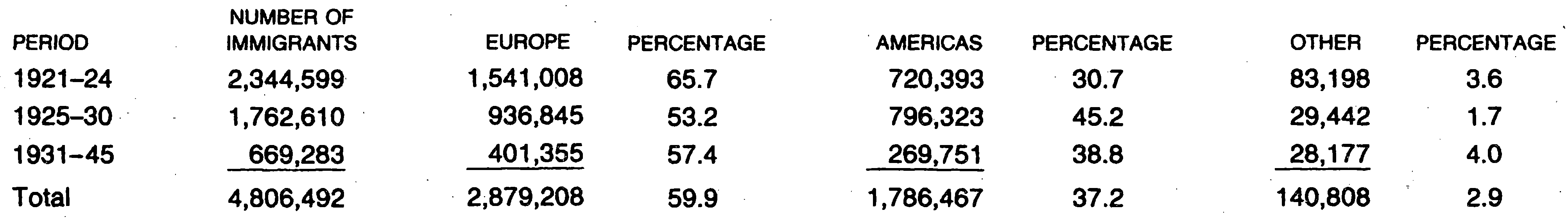

Table 11.3

Immigration, by Period and by Region, 1921–1945

The greatest increase in postwar immigration, reflecting in part patterns that had been established during the war, were the nations of the New World, particularly Canada and Mexico. In the prewar decade New World immigration had run at about 7 percent of the total and was increasing. During the war years—1915–20—about every fourth immigrant was from the Western Hemisphere, three-quarters of them from Canada and most of the rest from Mexico. During 1921–24 the Western Hemisphere percentage jumped to more than three-tenths of the total (31 percent). More than one hundred thousand Canadians came annually, as did more than fifty thousand Mexicans, while the rest of the hemisphere sent about twenty thousand.

1925–1930: The “Normal” Quota Years

The next six years saw an intensification of the new patterns: Immigration from Europe dropped, absolutely and relatively, while it continued to increase from the New World. Annual immigration, which had run at some 590,000 in the prior period dropped to about 295,000, a cut of 50 percent. If we just look at net emigration, the result is essentially the same: 435,000 annually in 1921–24 as opposed to 220,000 in 1925–30. Within Europe, the effects of the 1924 act could be clearly seen. The number of incoming Poles and Italians was slashed drastically: Only about 8,000 Poles and 15,000 Italians entered annually, representing a mere twelfth of all immigrants. Conversely, German immigration continued at a rate above its prewar level: Almost 45,000 Germans a year entered the country, and they represented more than a quarter of European immigrants and 15 percent of all newcomers. The favored immigrant groups from Northwestern Europe—British, Irish, Scandinavians, and Germans—accounted for 37 percent of all immigration and nearly 70 percent of that from Europe. This was precisely the kind of result that the sponsors of the 1924 act had envisaged.

In the meantime the incidence of immigration from the Americas, still almost exclusively Canadian and Mexican, increased by 50 percent. The nearly half million Canadians and the more than quarter million Mexicans recorded as entering immigrants were almost 95 percent of all immigrants from the New World. These increases had not been envisaged by most restrictionists and there were constant suggestions that the quota system be extended to the New World, but these were resisted in Congress partly because the agricultural interests of the Pacific Coast and Southwest insisted that they needed Mexican labor.

Although the total annual quota was about one hundred fifty thousand a year, actual immigration ran well above that. There were three reasons for this. First of all, as we have seen, the increasingly important immigration from the New World was not subject to any quota. Second, there had been, since 1921, provisions for nonquota immigrants from areas that were subject to quota. These included, after 1924, wives and dependent children of United States citizens—as long as they were not aliens ineligible to citizenship—resident aliens returning from visits abroad, ministers of religion and their immediate families, various professionals, and domestic servants. This introduced two entirely new factors into immigration legislation: family unification and a recognition of certain “skills,” although it should be noted that family unification had been recognized in the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907–8 negotiated between the United States and Japan. This meant that some European nationalities would exceed their quotas in some years, but in fact the total number of Europeans admitted under quota was below the maximum. The quota for Great Britain and Northern Ireland, for example, was some sixty-five thousand annually. It was never filled. And, finally, as the restrictions kept out more and more people, more and more individuals entered illegally, either by fraud, as was the case with paper sons, or by crossing the Mexican or Canadian border without a visa, by jumping ship, or by other means of entrance. One of the more common means of entry was to come on a visitor’s visa and simply stay. How many such persons were there? No one can be sure. It is what one expert has called the problem of “counting the uncountable.” There is no reason to believe that such persons were a major proportion of immigration in the 1920s and 1930s.

In addition, immigrants learned to cope with the new regulations. One method was to take up residence in a New World country: The law initially allowed anyone who had resided continuously in such a country for a period of one year to enter as a nonquota immigrant, provided, of course, that the prospective immigrant met all the other criteria—was not an Asian or a political subversive, did not have a loathsome disease, was literate, and so on. This loophole was soon partially blocked by increasing the residence period to five years, but it remained a method. The new law also required that prospective immigrants be interviewed by, and obtain a visa from, an American consulate. Prospective immigrants—or many of them—soon learned that it was easier to get a visa from certain consulates or consular officials than from others. And, finally, some were able to make marriages of convenience with American citizens and thus become instantly admissible.

To the leading advocates of restriction, the legislation of the 1920s was a qualified success. Their goals of reducing immigration—and reducing it from Eastern and Southern Europe in particular—had largely been met, although the average annual net migration of 220,000 was significantly higher than the 150,000 to 165,000 that was their stated goal. Most galling to them was the exemption of the Western Hemisphere from the quota system and the fact that Filipinos, though Asians, could continue to enter the United States as “nationals,” unaffected by immigration law, as long as the Philippines remained an American possession. Restrictionists did manage to get a bill through the Senate in 1930 that would have put Mexico, alone of Western Hemisphere nations, under the quota system, but the Hoover administration, which was trying to improve relations with Mexico and other Latin American countries, arranged to keep it bottled up in the House Rules Committee. (The details of Mexican and Filipino immigration will be discussed later.) Had economic and political conditions remained the same, had the relative prosperity of the 1920s been maintained and the world remained at peace, there is every reason to believe that the immigration patterns of 1925–30 would have continued: but, of course, things did not remain the same.

1931–1945: Depression and War

The Great Depression of the 1930s changed the patterns of immigration drastically. It is often stated, even, for example, in such an authoritative source as HEAEG, that “in the 1930s the number of people leaving the United States exceeded the number entering.”2 Although, as we have seen, there were four consecutive years—1932–35—in which the number of emigrants did exceed the number of entrants, the balance for the decade was positive. In the period July 1, 1930–June 30, 1940, 528,331 immigrants arrived and 459,738 resident aliens departed, leaving a positive balance of nearly 69,000 persons for the decade, an average of 6,900 per year. In 1914 more persons than that had entered the country every two days! Not reflected in these figures are the movements of American citizens, whether incoming persons such as the children of the returned Hungarian immigrants Lajos P. and Lea L., or of naturalized citizens who returned to their mother countries.

The great drop in the number of immigrants from 241,700 in 1930 and 97,139 in 1931 is one of the significant demarcation points in the history of American immigration. Not until 1946 would as many as 100,000 persons again enter the country as immigrants. There were two obvious causes for the decline. In the first place, the impact of the Great Depression was beginning to be felt. Every previous depression in American history had lowered the numbers of immigrants and the Great Depression had similar effects. In addition, the American government changed the rules and did so by executive order. In 1930 President Herbert Hoover issued an order to American consulates to interpret the long-standing LPC clause more rigidly. Previously, only persons who were obviously unable and/or unlikely to be able to support themselves had been kept out by that provision of the law: At one time the possession of twenty-five dollars had been enough. Now consular officials and officials of the INS were given discretionary powers, and it is clear that they used them. It is not now possible even to estimate how many were denied entrance on these grounds as no scholar has yet investigated the visa application files of the various consulates. In time many prospective immigrants had to get affidavits of support from relatives or others already in the country and those providing the affidavits had to be able to demonstrate to an often hostile officialdom that they could, in fact, support the immigrants if necessary. Although Franklin Roosevelt revoked the executive order in 1936, many in the consular and diplomatic services continued to interpret the LPC clause in the new and more restrictive way.

By the depths of the depression, many more immigrants were leaving the country than were entering it. Again, 1930–31 provides the watershed. Net immigration, which had been 191,039, fell to 35,257, and in 1932 began the four-year period when emigration exceeded immigration. In addition, as we shall see, the federal government assisted the departure of many thousands of destitute Mexican Americans who seem not to be counted in the emigration data. As we know, although it is not much talked about, emigration in sizable numbers has been a constant feature of American immigration history since the seventeenth century. Added to ordinary factors causing emigration in the 1930s was the simple fact that it is easier to be poor in a poor country than in a rich one and that many immigrants had support networks in the old country that did not exist in America.

The administrations of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, which changed almost every other aspect of American political, economic, and social life, made no attempt to alter the basic structure of immigration legislation or administration. There was no New Deal for immigration. As we have seen, FDR’s government even continued to apply the Hoover interpretation of the LPC after the executive order that promulgated it had been revoked. To be sure, Roosevelt, who attracted the votes of most recent immigrants and their descendants and gave numerous appointments to Catholics and Jews, who formed an important part of the triumphant Roosevelt coalition, did not indulge in nativist rhetoric. To the contrary, he sometimes twitted nativist groups, as in his celebrated remark to the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1938 when he urged them to “remember, remember always that all of us, and you and I especially, are descended from immigrants and revolutionaries.” Although no nativist by any criteria, Roosevelt did share with many nativists and other Americans the notion that, since the country was essentially completed—”our industrial plant is already built,” he once noted,—immigration was a thing of the past. I know of no evidence to suggest that he ever even considered asking for major changes in the National Origins Act.

This adherence to the status quo by our most innovative president led to one of the major moral blots on the American public record: our essential indifference to the fate of Jewish and other refugees from Hitler’s Third Reich. It is hard to improve on the judgment made by Vice President Walter Mondale in 1979 that the United States and other nations that could have offered asylum “failed the test of civilization.” The immigration acts of the 1920s made no distinction between “immigrants” and “refugees,” and the legislative debates that preceded them show little if any awareness of potential refugee problems.3 One leading nativist propagandist, Madison Grant, wrote in 1918:4

When the Bolshevists in Russia are overthrown, which is only a matter of time, there will be a great massacre of Jews and I suppose that we will get the overflow unless we can stop it.

Such anticipations were unusual. Without in any way minimizing the widespread anti-Semitism in American life in the 1920s, especially among the elite, almost all of those who participated in the great debates over immigration policy assumed that the future would resemble the past and that most of those who would try to come to the United States would be attracted for economic reasons, not to save their lives. Thus, refugees from Germany had to surmount barriers that were, in many instances, unsurmountable. And the progressive president in the White House, the political idol of most American Jews, was not willing to swim against the current by attempting to get changes or exceptions made in the law.

From his very first days in office—Hitler had preceded him in power by a little over a month—FDR was made aware of what was happening in Germany and, as a liberal, humane democrat, deplored it. As chief executive, however, he consistently took the advice of his conservative State Department. When, for example, Felix Frankfurter and Raymond Moley urged him to send representatives to a 1936 League of Nations conference on Jewish and non-Jewish refugees and to appoint the outstanding American Jewish leader, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, to the delegation, Roosevelt instead followed the State Department’s advice and sent only a minor functionary as an observer. Secretary of State Cordell Hull told him that: “. . . the status of all aliens is covered by law and there is no latitude left to the Executive to discuss questions concerning the legal status of aliens.” FDR, who could usually find a way to do what he wanted to do, in this and other instances involving refugees, meekly accepted the doctrine of executive impotence in the face of congressional will.

Similarly, when Herbert H. Lehman (1878–1963), Roosevelt’s successor as governor of New York, wrote him about the difficulty German Jews were having in getting visas from American consulates in Germany, FDR, on two separate occasions in 1935 and 1936, sent replies that had been drafted by the State Department. In each instance, the response assured Lehman of the president’s “sympathetic interest,” but insisted that “the Department of State and its consular officials abroad are continuing to make every effort to carry out the immigration duties placed upon them in a considerate and humane manner.” Lehman was also assured that a visa would be issued in any instance

when the preponderance of evidence supports a conclusion that the person promising the applicant’s support will be likely to take steps to prevent the applicant from becoming a public charge.

Irrefutable evidence exists in a number of places to demonstrate that, despite these assurances at the very highest levels of government, the State Department consistently made it difficult for most refugees to enter this country. Let me illustrate what I mean by a brief account of the problems encountered by the nation’s oldest Jewish seminary, Hebrew Union College (HUC) in Cincinnati, in its Refugee Scholars Project. These incidents, which are all too typical, are taken from Michael A. Meyer’s history of the college.5 The project, which was operational between 1935 and 1942, eventually brought eleven refugee scholars to Cincinnati. Most of those came under the provisions—already noted—of the 1924 act, which exempted from quota restriction

an immigrant who continuously for at least two years immediately preceding the time of his application for his admission to the United States has been, and seeks to enter the United States solely for the purpose of, carrying on the vocation of minister of any religious denomination, or professor of a college, academy, seminary, or university, and his wife, and his unmarried children under 18 years of age, if accompanying or following to join him.

Although of little use to the mass of refugees or would-be refugees, these provisions seemed a godsend for the kinds of people HUC wanted to bring out. The State Department, however, and especially Avra M. Warren, head of its Visa Division, continually raised—one is tempted to say “invented”—difficulties. In most instances the college, sometimes by enlisting the support of influential individuals, managed to overcome them. In the cases of Arthur Spanier and Albert Lewkowitz, however, the difficulties proved insurmountable. Spanier, once Hebraica librarian at the Prussian State Library and later a teacher at the former Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums in Berlin (a Hochschule in Germany was and is an institution of higher education, not a high school), had been sent to a concentration camp after Kristallnacht—the night of broken glass—the anti-Jewish pogrom of November 1938. The guaranteed offer of an appointment from HUC was enough to get him released from the concentration camp but not enough to get him a visa from the American consulate. A visit to the State Department by HUC president Julian Morgenstern was necessary before the reasons for refusal could be discovered. According to Warren, Spanier was primarily a librarian. His teaching at the Hochschule, where he had taught for more than the two years stipulated by the law, was not acceptable to the State Department because in 1934 the Nazis had demoted the Hochschule from its former status as an institution of higher education, and an administrative regulation of the State Department, not found in the statute, held that the grant of a nonquota visa to a scholar coming from an institution of lesser status abroad to one of higher status in the United States was not permitted.

Spanier and the other scholar, Albert Lewkowitz, managed to get out of Germany, but to a country, the Netherlands, which soon fell under the Nazi heel. It had seemed that Lewkowitz, at least, was likely to get out since he had been a teacher of Jewish philosophy at the Breslau Jewish Theological Seminary, an institution whose status the State Department did not question. (In fact, both the Hochschule and the Seminary had been the leading institutions of their kind in the world before the Nazis came to power.) But the German bombing of Rotterdam in May 1940 destroyed the copies of Lewkowitz’s records, and officials at the American consulate there insisted on the impossible: that Lewkowitz get new documents from Germany before they would issue him a visa. Five years earlier, in peacetime, Roosevelt had assured Lehman that

consular officials have been instructed that in cases where it is found that an immigrant visa applicant cannot obtain a supporting document normally required by the Immigration Act of 1924 without the peculiar delay and embarrassment that might attend the request of a political or religious refugee, the requirement of such documentation may be waived on the basis of its not being “available.”

No such waiver was made for Lewkowitz. Neither he nor Spanier ever obtained visas and both were eventually sent to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Lewkowitz was one of the few concentration camp inmates exchanged in 1944, and he was permitted to enter Palestine. Spanier died in Bergen-Belsen. If relatively eminent individuals with a prestigious American sponsor such as these had difficulties, imagine what it must have been for less prominent persons.

Other horror stories could be told. In Congress, for example, the bipartisan Rogers-Wagner bill, which would have brought twenty thousand German refugee children—most of whom would have been Jewish—to the United States as nonquota immigrants, died in committee without ever having been voted up or down and without ever receiving a word of public support from the president. Its opponents argued publicly that it was just a ploy to undermine the quota system; privately they sneered that the “cute Jewish kids” would grow up to be “ugly Jewish adults.” No such problems arose in 1940 when Congress expedited plans—never fully carried out—to admit fifteen thousand children from war-torn Britain. Or, for a final example, there was the 1939 case of the German vessel Saint Louis, loaded with nearly a thousand refugees whose Cuban visas were canceled: Attempts were made to get them admitted to the United States and the ship sailed close enough to Miami Beach for its passengers to hear the music being played at the beachfront hotels. No admission was granted and its refugee passengers were returned to Europe. Many of them died in the Holocaust.

A number of German refugees, perhaps a total of 150,000, the vast majority of them Jews, did manage to get to the United States. This was well under the German quota. For the years 1933–40 there were 211,895 German quota spaces. Only 100,987 were actually used. Prominent refugees—such as Nobel Prize winners Albert Einstein (1879–1955) and Thomas Mann (1875–1955)—had few problems entering the country. Less prominent persons had great difficulty. Finally, in 1938, in the wake of Kristallnacht, Franklin Roosevelt used a little of his executive authority in the interests of refugees. He ordered that any political refugees already in the United States on visitor’s visas could have them extended and reextended every six months. This helped perhaps 15,000 persons here not to have to go back. At the same time, however, his spokesman, Myron C. Taylor assured the public in a radio address that:

Our plans do not involve the “flooding” of this or any other country with aliens of any race or creed. On the contrary, our entire program is based on the existing immigration laws of all the countries concerned, and. I am confident that within that framework our problem can be solved.

Taylor’s—and presumably Roosevelt’s—confidence was misplaced, if it in fact existed. Nothing short of a drastic revision or emergency suspension of American immigration laws could have saved a substantial number of refugees after 1938. That was a risk that FDR was not willing to take. The notion of the country being “flooded” was, of course, absurd. Neither gross nor net immigration in the 1930s even approached the quota limits. But the clutch of nativism, exacerbated by the very real problems of the depression, made such chimeras loom large in the minds of many Americans, in and out of Congress. And so, nothing much was done.

After the fall of France, in the summer of 1940, FDR asked his Advisory Committee on Refugees to make lists of eminent refugees and then ordered the State Department to issue temporary visitors’ visas to those individuals. The State Department’s own reports, which are not always reliable, indicate that it issued 3,268 such visas to

those of superior intellectual attainment, of indomitable spirit, experienced in vigorous support of the principles of liberal government and who are in danger of persecution or death at the hands of autocracy.

In the event, however, only about a third of them were ever used.

Once the United States itself was at war, there was another reason advanced for not letting refugees in: Nazi spies and saboteurs might be hidden among them. Only in 1944, when the incredible dimensions of the Holocaust began to be realized, when responsible officials could no longer refuse to take cognizance of what Walter Laqueur has called “the terrible secret,” did Washington take any further action. Then Roosevelt, by executive order, created the War Refugee Board (WRB). Although the WRB did not bring any refugees to the United States, it did—by using a mixture of public and private funds and unorthodox methods—assist in the rescue of the remnants of European Jewry. And Roosevelt himself, allowed one “token shipment” of 987 “carefully selected” refugees from displaced persons (DP) camps in Italy to a temporary haven in Oswego, New York. Theoretically the president had merely “paroled” the refugees into the United States temporarily, but in fact almost all of them became permanent residents and eventually citizens. Had such actions been taken earlier, the refugee story might have been substantially different, but there is no conceivable way that the United States could have rescued any more than a small fraction of the six million persons who perished in the Holocaust.

It is now abundantly clear that, as a group, the refugees who were successful in reaching the United States, have made a contribution to our culture highly disproportionate to their number. Many of those who contributed most to the making of the atomic bomb were refugees: in addition to Einstein, whose enormous prestige enabled him to convince Roosevelt that what became the Manhattan Project should be undertaken, refugee scientists such as Enrico Fermi (1901–54) from Italy, Leo Szilard (1898–1964) from Hungary, Lise Meitner (1878—1968) from Austria, did much of the crucial work that made nuclear fission in 1945 possible. In other fields as well, towering figures came to the United States: In music, for example, the composers Arnold Schönberg (1874–1951) from Austria and Béla Bartók (1881–1945) from Hungary, and dozens of topflight musicians and conductors came. Hundreds of academics in various disciplines helped transform and improve the level of intellectual life in America. In addition, many persons who came here as youngsters have made their presence felt, such as the fifteen-year-old Heinz Kissinger who arrived with his family from Germany in 1938 and grew up to become secretary of state.

Asian Americans and World War II

World War II had diametrically opposed impacts on the two major Asian American ethnic groups. Japanese Americans, in a betrayal of almost everything that America is supposed to stand for, were rounded up and shipped off to ten godforsaken concentration camps in places like “Topaz,” Utah. Chinese Americans, on the other hand, saw their legal position transformed as they, but not other Asians and Asian Americans, were placed almost on a par with other immigrant and ethnic groups insofar as immigration and naturalization were concerned. Each group was only a tiny segment of the American population: In 1940 there were about 125,000 Japanese Americans and 75,000 Chinese Americans in the contiguous United States, less than two-tenths of 1 percent of the population. Nothing better symbolizes the ambiguous relationship between war and democracy than the contrasting fates of these two populations.

Although the United States fought against totalitarianism and racism in World War II, one of its most significant acts on the home front was to adapt one of the institutions of its most feared opponent—the concentration camp—for use against the Japanese Americans. In addition, of course, the largest American racial minority, blacks, were still legally second-class citizens, segregated in those states where the overwhelming majority of them lived and in the military forces raised by the federal government.

During World War I, as we have seen, the huge German American ethnic group had been badly mistreated, although none of that mistreatment came from federal statutes. (In Canada, by contrast, many naturalized German Canadians had their citizenship revoked during the 1914–18 war.) During World War II, happily, the American government and people made clear distinctions between what the propaganda called “good” and “bad” Germans (and Italians). The vast majority of unnaturalized Germans and Italians in the United States were left at liberty, even though they—and all other aliens—had been required by a law passed in 1940 to register annually as long as they remained in the United States. American entry into the war, in December 1941, transformed resident-alien Germans, Italians, and Japanese into “enemy aliens.” It must be remembered that, since they were “aliens ineligible to citizenship,” the Japanese, unlike the others, were noncitizens by necessity, not choice or oversight. Under the normal wartime enemy alien procedures, about two thousand Japanese aliens, almost all of them adult males, were rounded up and placed in confinement, as were proportionally fewer alien Germans and a handful of Italian aliens. (Enemy alien status for almost all the millions of unnaturalized Italians was lifted in a Columbus Day proclamation in 1942 in a move that had more to do with the forthcoming congressional elections than with honoring the Genoese navigator.) While it is clear that alien Japanese were being treated more harshly than were Caucasian enemy aliens, these incarcerations left most Japanese Americans at liberty and did no violence to the Constitution.

By February 1942, however, under the impact of a string of humiliating defeats by Japan and a rising chorus of anti-Japanese sentiment from the media, politicians, and many ordinary Americans, Franklin Roosevelt began the process whereby 120,000 Japanese Americans—more than two-thirds of them native-born American citizens—were herded into ten hurriedly built concentration camps, where some of them remained for almost four years.6

Over the years most Americans have come to see, as President Gerald R. Ford put it in a 1976 proclamation:

We know now what we should have known then—not only was that evacuation wrong, but Japanese Americans were and are loyal Americans.

More specifically, the presidential Commission on the Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians concluded in 1983 that the wartime mistreatment of Japanese Americans

was not justified by military necessity, and the decisions which followed from it—detention, ending detention and ending exclusion—were not driven by analysis of military conditions. The broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.7

Six years later, in 1988, Congress passed, and President Ronald W. Reagan signed, a bill containing an apology to the Japanese American people for the injustice done them and authorizing the payment of twenty thousand dollars in “redress” to each of the perhaps sixty thousand surviving persons who had been in one of America’s concentration camps. Almost fifty years earlier, however, the incarceration of the Japanese had been a popular wartime act. Most Americans not only approved what was done but would have approved harsher treatment. Many indicated that all Japanese should be deported after the war was over.

Thus, Japanese Americans suffered for the actions of Japan; Chinese Americans, conversely, benefited from the wartime popularity, relatively speaking, of China. American support for China, which had been one of the causes of the great Pacific war between Japan and the United States, had manifested itself off and on during the twentieth century but had not been of any real assistance to Chinese Americans. In 1943, however, as a gesture toward a wartime ally, Franklin Roosevelt recommended and Congress agreed to repeal the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and all or part of fourteen other statutes that had effected Chinese exclusion. In addition, the new law gave a quota of 105 persons annually to “persons of the Chinese race” and amended the nationality act to make “Chinese persons or persons of Chinese descent” eligible for naturalization on the same terms as other immigrants. It is clear that both Congress and the president regarded this action as a kind of good behavior prize. As Roosevelt put it:

It is with particular pride and pleasure that I have today signed the bill repealing the Chinese exclusion laws. The Chinese people, I am sure, will take pleasure in knowing that this represents a manifestation on the part of the American people of their affection and regard.

An unfortunate barrier between allies has been removed. The war effort in the Far East can now be carried on with a greater vigor and a larger understanding of our common purpose.

Although American immigration law was still discriminatory toward Chinese—a Canadian-born Chinese entering the United States as an immigrant would have to secure one of the 105 Chinese quota slots—we can now see that, just as the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act had been the hinge on which the golden door of American immigration began to swing closed, its repeal six decades later was, similarly, the hinge on which it began its renewed outward swing. In addition, a little-noticed 1946 act, which made the alien Chinese wives of American citizens admissible on a nonquota basis, had important demographic consequences for the Chinese American community. During the eight years 1945–52, when there were a total of 840 Chinese quota slots, just over 11,000 Chinese actually emigrated to the United States. Nearly 10,000 of these were women, almost all of them nonquota wives. When one considers that, as late as 1950, the Chinese American community of 117,000 contained only 28,000 women 14 years of age and older, the demographic impact of these women was obvious. In addition, this act presaged what would be a major theme of American immigration policy in the post–World War II years: family reunification.

World War II also saw the beginnings of what is usually called cultural pluralism in the ways in which most Americans defined their cultural identity. As Philip Gleason has written, the war gave unprecedented salience to ideology:

For a whole generation, the question “What does it mean to be an American?” was answered primarily by reference to “the values America stands for”: democracy, freedom, equality, respect for individual dignity, and so on. Since these values were abstract and universal, American identity could not be linked exclusively with any single ethnic deprivation. Persons of any race, color, religion or background could be, or become, Americans.8

Despite this sea change in American ideology, which would be intensified during the Cold War, the nation’s basic immigration law remained the national origins system set up during 1924–29. It would prevail, at least on paper, until 1965. But, as we shall see, the period between 1943, when Chinese Exclusion was ended, and 1965 when the whole structure was scrapped, was one of gradual relaxation of the laws and a progressive increase in the number of immigrants who entered the country.

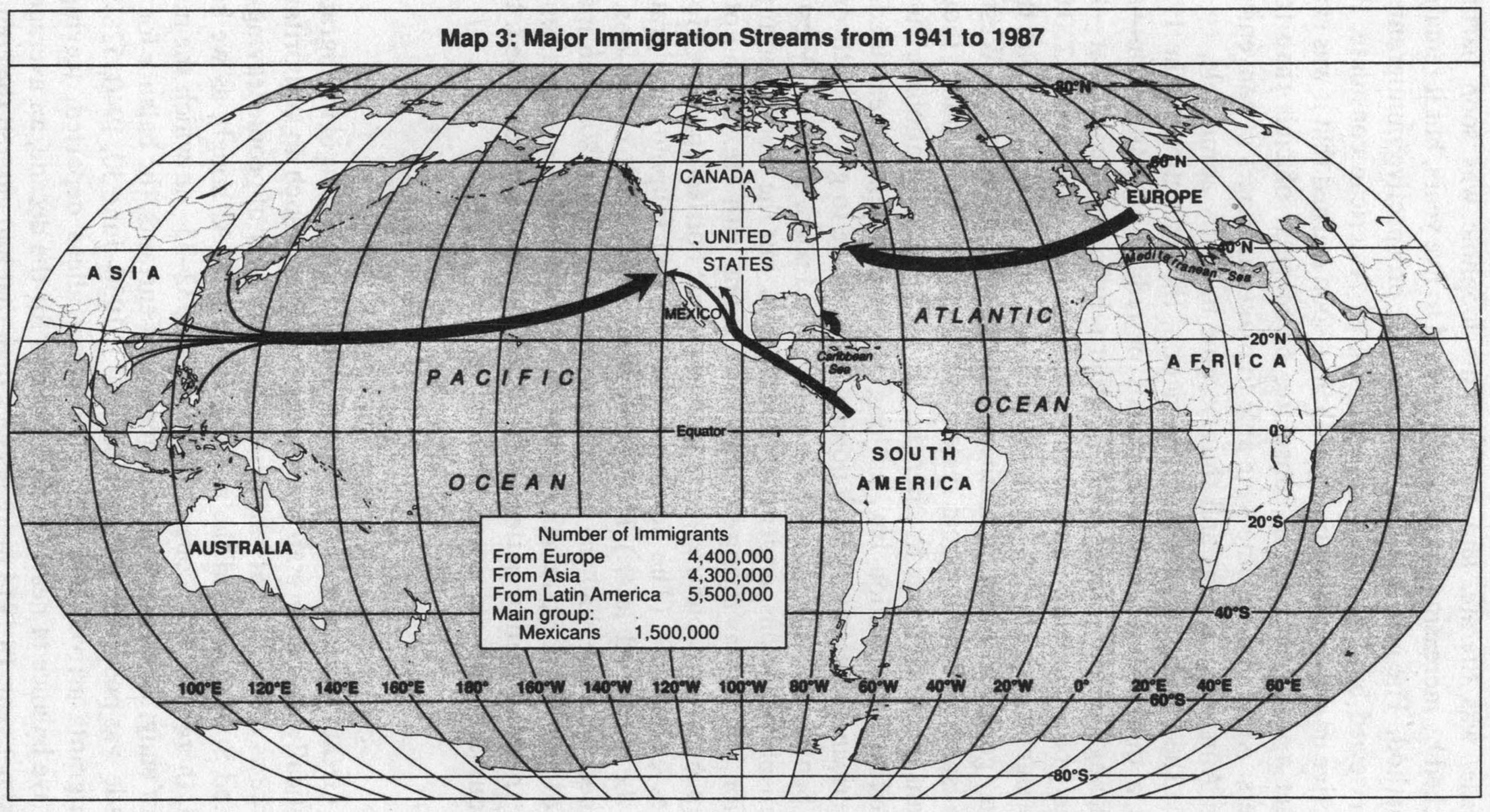

One other major change occurred during the war years. A labor shortage, after the glut and longterm mass unemployment of the 1930s, caused the United States deliberately to stimulate the migration of Mexican laborers to work in the agriculture of the American Southwest and West and on America’s railroads. This so-called bracero program—from the Spanish bracer, “arm,” therefore a manual worker—is an important landmark in the history of Latin American migration to the United States. In the first two decades of this century immigrants from Latin America accounted for just 4 percent of all immigrants: Since the 1960s they have accounted for more than a third of all legal immigrants, to which must be added several millions of illegal immigrants, those who simply crossed the border without the permission of the government. In the war years, and after, the notion was that Mexicans would be temporary workers, what the Germans have come to call Gastarbeiter, guest workers. While many imported temporary workers were just that—persons who went home after the growing season or the labor shortage was over—many others stayed on to become permanent residents, with or without the proper papers. But the Mexican American experience was not something that began with the war: As we have seen, it was Spanish Mexicans who were the pioneers of the American Southwest and much of the West Coast. In the next chapter we shall pick up their story in the mid-nineteenth century and bring it up to the very recent past.