10

The Powers of Operative Witchcraft

The animals gather together

Or else are put to flight

By certain fumes the horses stop

And day turns into night

THE HORSE WITCH

Accounts of witches in England in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries tell of their stopping horses and carts at a distance and refusing to let them move until rewarded in some way. At Longstanton in Cambridgeshire, the reputed witch Bet Cross is said to have stopped horses outside her garden, and horses were stopped by witches in the witchcraft centers of Horseheath Histon and Wisbech (M.G.C.H. 1936, 507; Parsons 1915, 41; Porter 1969, 57). A Herefordshire account of horse stopping was told to the Herefordshire folklorist Ella Mary Leather by an inmate of the workhouse at Ross who remembered “going over Whitney bridge . . . when behind the cart he was driving came a waggoner with three horses, and had no money to pay toll. He defied the old woman at the toll house, and would have driven past her, but she witched the horses so that they would not move” (Leather 1912, 55).

Another typical example of how a horse could be stopped comes from a story from Upwood, Huntingdonshire, related in 1927. A man was bringing home a load of wheat and his wagon stopped unexpectedly, and the horses refused to move any farther. After a while, an old woman came from her cottage nearby, picked up a straw from the road, and then the horses proceeded without difficulty (Tebbutt 1984, 84–85). It is clear that the straw was doused in a jading substance perhaps as an experiment. Clearly, it appeared to be a form of magic to anyone not in the know; hence, the story that the woman was a witch. The suddenness with which horses could be made to stop was described by the horsewoman Ida Sadler as stopped “as if they were shot” (Sadler 1962, 15).

An ability to make a horse stop and stand motionless until bidden to go again was an essential skill in a society that relied on real horsepower. A drinking toast from the Horseman’s Grip and Word society in Scotland praises this ability.

Here’s to the yoke that our forefathers broke,

And here’s to the plough that was hidden.

Here’s to the horse that can pull

And stand like a stone when bidden.

(RENNIE ET AL. 2009, 121)

This ability was not usually connected with the evil eye, for it was a practical ability of men who worked with horses who had been taught it as part of their membership in the Society of the Horseman’s Word, the Whisper, or the Confraternity of the Plough. Horses, having evolved as grazing animals with no defense against predators except speed, are extremely sensitive animals. They have senses of hearing and smell far superior to that of humans and a high level of awareness and sensitivity to their surroundings. These hypersensitive characteristics were used by those in the know to control horses. This is why “horses are thought to be peculiarly susceptible to witchcraft” (Leather 1912, 23).

The materia magica for drawing (calling) horses to one, or for taming unruly or vicious horses, are various oils that play on a horse’s refined sense of smell. Aromatic oils that attract horses are known as drawing oils. One concoction favored in East Anglia is a particular mixture of the oils of cinnamon, fennel, oregano, and rosemary. The user dabs some drawing oil on his or her forehead and stands upwind of the horse to attract it. Aniseed and crushed hemp seed also draw horses to the person carrying them. Those who control horses in this way carry a walking stick that has a notch or small cavity just above the ferrule, where drawing oil is hidden on a piece of cotton wool (Evans 1971, 210). A woman who can attract horses in this way or control other animals and people by similar methods is an old biddie, for it is she who bids them to do her will.

Animals that comply are always rewarded with a stroke, a kind word, and a “sweetener,” something sweet, such as sugar, gingerbread, and other sweet-scented cakes. These treats are given at the same time as other actions are performed—gestures and movements and sounds—that condition the horse to behave in a particular way. This is the principle of all animal training, long before Pavlov’s experiments on salivating dogs gave it a scientific name, the conditioned reflex. The connection between the horse and the horseman is very close. “It was at one time the custom to tell cart horses of the death of their master,” Leather noted in Herefordshire in 1912 (Leather 1912, 23).

Stopping horses also uses substances with a certain kind of strong smell—evil-smelling substances called jading materials. Put in front of a horse, these substances will make it stop and refuse to move until they are taken away. One recipe for horse stopping is to use the dried and powdered liver of a rabbit or stoat mixed with dragon’s blood, a natural resin (Evans 1971, 208). Another is to use a pounded mixture of rue, feverfew, and hemlock, rubbed on the horse’s nose. An ointment made by boiling cuckoo flowers and bay leaves, smeared on the stable door, keeps the horses in (Porter 1969, 93–94).

Another important material in the materia magica of horsemanry is the pad of fibrous material that lies beneath the tongue of the fetal foal. It is taken out at birth and can be combined with drawing substances (Evans 1971, 214). This pad is known as the meld in Cambridgeshire; in Norfolk and Suffolk, it is called the milt, milch, or melt.

An oil is prepared from the meld, which is steamed to extract an oil that is mixed with oil of rhodium and attar of roses, and then kept in a bottle. The horseman puts drops of this oil on his glove when feeding or handling stallions to keep them docile (John Thorn, personal communication; Evans 1971, 214–15; Bayliss 1997, 13). The meld is also dried in an oven until it hardens, then it is pounded to powder, mixed with olive oil, and baked. The resulting material is put in a muslin bag and kept under the horseman’s right armpit. There, it absorbs sweat with the horseman’s personal odor, which is used to teach the horse the horseman’s individual smell. In the past, there are records of people identifying other people by their smell, as recorded in the Sturbridge Initiation at the fair once held at Barnwell near Cambridge.

Over thy head I ring this bell,

Because thou art an infidel.

And I know thee by thy smell.

(HONE 1828, VOL. 2, 1,548)

Newmarket has been a major center of horse racing for centuries. The lore and techniques of horsemanry have, of course, always been strong there. One magical technique recorded from the grooms at Newmarket involves a frog-bone ritual: “Grooms catch a frog and keep it in a bottle or tin until nothing but the bones remain. At New Moon they draw these up stream in running water; one of the bones which floats is kept as a charm in the pocket or hung round the neck. This gives the man the power to control any horse, however vicious it may be” (Burn 1914, 363–64). The V-shaped piece of hornlike material on the underside of a horse’s hoof is also called the frog. The “full brace” of horn buttons of the traditional Suffolk horseman’s suit have this V facing downward, with seven colored points above it to signify the seven nails of the horseshoe. They also signify the seven stars, the constellation known as the Plough, referred to in the horseman’s toast here, “the plough that was hidden” (Tony Harvey, personal communication).

Men and women who worked with horses and knew the tricks of the trade trained their horses to perform certain actions that were not strictly necessary for their work. During the era when witchcraft was a punishable offense, people who showed off their skills with horses ran the risk of prosecution and capital punishment. In 1664 in Renfrewshire, a lad was arrested on a charge of witchcraft because “for a halfpenny he would make a horse stand still in the plough, at the word of command by turning himself widdershins or contrary to the course of the sun” (Davidson 1956, 71). We can recognize this effect of the word and a particular action on horses as a conditioned reflex that the horses had been trained to do. To those who were not in on the secret, this was supernatural, a performance that only someone in league with the devil could possibly attempt.

An example of this was recorded by Arthur Randall in his book Sixty Years a Fenman. When he was working on a farm near King’s Lynn, Norfolk, in 1911, a horseman once asked him, “Have you ever seen the Devil, bor?” Shocked, Randall answered that he had not and hoped he never would. Then the horseman said, “Well I have, many a time, and what’s more, I’ll show you something.” Then he demonstrated his power. He thrust a two-pronged fork into a dunghill, and the horse was harnessed up to it. The horse was told to pull, but however hard it pulled, it was unable to pull the fork out of the dunghill. Then the horseman released it, and it could. After demonstrating his powers, the horseman warned the young Randall, “Don’t you tell nobody what you’ve just seen, bor” (Randall 1966, 109–10).

The secret knowledge of horse training was kept among those who were members of the rural fraternities and those who had found out how to do it by other means. There was no theory, only the practice of horsemanry, so in all probability even those who could control horses could not explain how it was done, even if they were not bound under oath and pain of death never to reveal the secret to an outsider. In 1962, Sadler wrote a short memoir on her fifty years working with horses with two anecdotes that show this training in action. Sadler tells how her grandfather, who was a “great horseman,” was in a Suffolk pub and a man there bet him a gallon of beer that he could not get his horses out of the stable with their halters off and drive them around in front of the pub. “He had four Suffolk horses—called them out of the stable—put two in the double-breasted waggon shafts and two on the tree (that’s in front of the other two). He got in the waggon and drove them to the front of the pub and had the gallon of beer” (Sadler 1962, 15). Also, she once had a young mare on a set of harrows and was leading her as it was a windy day. “Suddenly, she [the horse] gave a jump and somehow the snop on the lead came undone, and away she went full gallop around a seven-acre field, back to me, turned a circle, and stopped right beside her” (Sadler 1962, 15).

FAMILIAR SPIRITS

She said she had a spirit in the likeness of a yellow dun cat.

(WITCH’S “CONFESSION,” GIFFORD 1607)

The laws against witches and conjuration state, “These witches have ordinarily a familiar or spirit, which appeareth to them: sometime in one shape, sometime in another, as in the shape of a man, woman, boy, dogge, catte, foale, fowl, hare, rat, toad, etc.” (Ashton 1896, 159). One of the duties ascribed to the familiar by the witchfinders was to act as a messenger between the devil and the witch, keeping her informed of the place of the next convent of the witches with their master. The time was already known: after midnight on Friday was the Sabbat. Women were sometimes accused by witchfinders during the witch hunts of transmogrifying into animals themselves, confusing the issue about familiars. The belief in witch transmogrification continued long after the moral panic about witchcraft, into the twentieth century. In 1901, Mabel Peacock wrote of Lincolnshire “people suspected of ‘knowing more than they should,’” stating that “one of these students of unholy lore could, according to belief, assume the shape of a dog or toad at will, when bent on injuring his neighbour’s cattle. As a dog he was supposed to worry oxen and sheep, while under the form of a toad, he poisoned the feeding-trough of the pigs” (Peacock 1901a, 172; 1901b, 510).

Familiar or pet names were often brought out as evidence at trials of those accused of witchcraft. Although household animals, and many farm animals, were given their own names, the witch hunters saw in certain of them, especially the more unusual ones, some nefarious intentions. The recorded ones have a notable variety, for they contain some names documented nowhere else, also the names of spirits and deities: Elimanzer, Tom Twit, Vinegar Tom, Thomas a Fearie, Makeshift, Hob, Holt, Hell-Blaw, Bonnie, Brauny, Great Browning, Little Browning, Jarmara, Jesus, Jupiter, Venus, Rutterkin, Robin Goodfellow, Lunch, Newes, Little Rodin, Griezzell Greedigut, Sackin, Sacke-and-Sugar, Spirit, Son of Art, Piggin, Peck in the Crown, Pyewackett, Lierd, Lightfoot, Pluck, Puppet, Blue Cap, Red Cap, Ball, Bid, Tib, Jill, Will, Willet, William, and Walliman (Rosen 1991, 382; Wilby 2000, 288, 296; Palmer 2004, 147).

In 1607, George Gifford reported that a woman accused of witchcraft had confessed that she had three spirits: one, called Lightfoot, was like a cat, another, called Lunch, like a toad, and the third, like a weasel, she called Makeshift. Lunch, the toad, “would plague men in their bodies” (Gifford 1607; Hutchinson 1966, 226). During the English Civil War, Parliamentarians asserted that Boy, the white poodle dog belonging to Prince Rupert, was not a real dog but rather a familiar spirit. The German dog accompanied him everywhere, even under fire on the battlefield, and seemed to be invulnerable. Only at Marston Moor, the site of the Royalists’ decisive defeat, was the dog hit by a bullet, from which it died. Later in 1644, a Parliament supporter in London published a pamphlet about the event, where the dead dog was given a voice and said he was not really a German dog but came from Lapland or Finland “where there none but Divells and Sorcerers live.” The pamphlet said that Boy was shot at the Battle of Marston Moor with a silver bullet fired “by a valiant souldier, who had skill in Necromancy.” There was a mock invitation that read, “Sad Cavaliers, Rupert invites you all, that doe survive, to his Dog’s Funeral. Close mourners are the Witch, Pope and Devill that much lament yo’r late befallen evil.” This political text shows how close the connection was at that time between sectarianism, factionalism, and the labeling of one’s enemies as practitioners of diabolical witchcraft (Ashton 1896, 162–63).

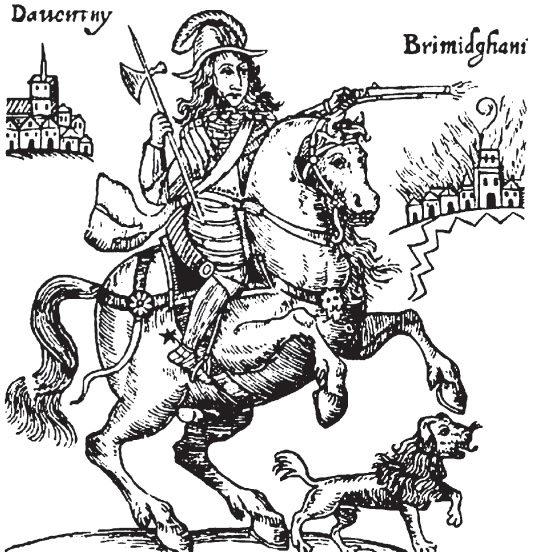

Fig. 10.1. Prince Rupert and his dog Boy, with the city of Birmingham burning behind them

Just as people were sometimes accused of witchcraft for controlling horses in an unnatural and spectacular way, so were people who trained dogs, cats, and other animals. Long after it could prove fatal to own animals that looked or behaved unusually, people still played on the fears of gullible neighbors with trained animals. At Willingham, north of Cambridge, Jabez Few, who died in the late 1920s, was a practical joker who called his trained white rats “imps” (Porter 1969, 175–76). Neighbors were terrified of them.

The name Old Mother Redcap has been carried by several women believed to be witches. The most famous Old Mother Redcap was an alewife in medieval London whose given name was Elinor Rummynge, and the connection between brewing and the concoction of medicines and other substances is direct. The name Red Cap also appears among the Horseheath imps, which were supposed to be kept in a box somewhere in the village. According to Catherine Parsons, these imps were named Bonnie, Blue Cap, Red Cap, Jupiter, and Venus. Unlike their keepers, they were immortal and had to be handed on. In 1915, Parsons announced that they were then in the keeping of a woman from Castle Camps (Parsons 1915). A newspaper report of 1928 recounts that a black man called at a house in Horseheath and asked the woman there to sign a receipt book. If she did, she was told that she would be the mistress of five imps. Shortly afterward, the woman was seen accompanied by a cat, a rat, a ferret, a mouse, and a toad. After that, her neighbors believed her to be a witch, and many people visited her to obtain cures (Robbins 1963, 556).

Fig. 10.2. Crosses over the door and windows in a Victorian terraced house in Cambridge