Chapter Three

The Battle of the Somme 1916

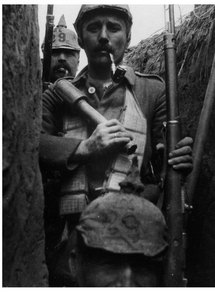

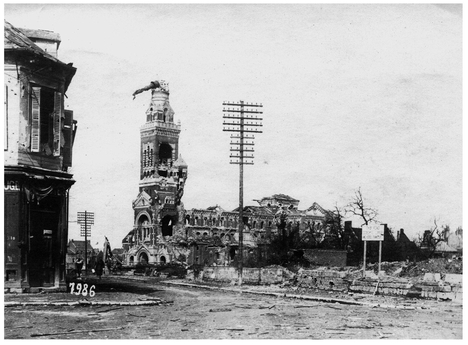

In October 1914 (the ‘Race to the Sea’), after brief but fierce fighting against the French Army, the Germans established themselves along the Somme. With the beginning of trench warfare from about mid-November 1914, a seventy-kilometre long front line came into existence, increasingly strongly fortified, which stretched on the north-south axis through the villages of Gommecourt, Beaumont-Hamel, Thiepval, Fricourt, Maricourt, Curlu (following a bend there in the Somme) to Dompierre, Fay, Chaulnes and Maucourt. For twenty-one months, 2. Army under General Fritz von Below expanded its infantry and communications trenches north and south of the river, ‘wired up’ woodlands and barricaded villages abandoned by their populations. In some places they created bunker-like refuges and soldiers’ accommodation (such as the ‘Swabian Fort’ at Thiepval) or dug underground galleries – often up to twelve metres deep.

Artillery fire was exchanged regularly, mines were used (Fricourt, Fay) and attacks made against enemy trenches, but the only major battle between Germans and French, in June 1915 at Serre in the north of the Somme region, made no significant change to the front. At the end of January 1916, 11.Bavarian Inf.Div. captured the small village of Frise at the entrance to the Somme bend. When the Allied offensive began in July 1916, the Germans had north of the Somme, under the command of General Hermann von Stein, commanding-general XVII Army Corps, five full strength divisions plus two-thirds of 10.Bavarian Inf.Div. South of the river under General von Pannewitz, commanding general XVII Army Corps, were four divisions, a Garde-Corps with subordinated Landwehr division and behind these. to the east, three reserve divisions and one-third 10. Bavarian Inf.Div.1 The total strength of the German force (including the technical units) on the Somme was initially 300,000 men. Opposing them in trenches on the eve of the offensive were 500,000 British and 200,000 French troops. Many participants and also entire units of these armies were colonial or from the British dominions of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa.2

Prelude

The decision of the Entente to attempt the breakthrough in 1916 and put an end to trench warfare, and the war of attrition, was taken in December 1915 in a conference at Chantilly north of Paris. The Germans were to be attacked simultaneously in all theatres in order to give them no opportunity to transfer their reserves from one front to the other. The exact location and time of the General Offensive in the west was not agreed at Chantilly, and not until 14 February 1916 did the respective commanders-in-chief, Joffre and Haig, agree on eastern Picardy. Especially from the French point of view, the Somme region was chosen for its topography and the nature of the landscape. The hilly terrain and chalky ground promised a firmer subsoil than the heavy mires of Flanders – and the fact that there, at the seam between the Allied armies as it were, a close military cooperation between them would be possible from early on. Joffre and Haig agreed initially that the French would lead the main assault with the British playing only a supporting role. The strength of the French Army operating south of the Somme river was set at forty divisions with 1,700 heavy guns.

The German attack on Verdun on 21 February 1916 with bitter fighting and very heavy casualties north of the city and west of the Meuse put a stop to the Allied plan. The number of operational French divisions on the Somme was cut at once to twenty-two and for the attack itself the C-in-C French 6th Army, General Marie Émile Fayolle, was left with only twelve whole divisions for the fifteen kilometres of front under his control. The main weight of the military operations scheduled to begin around 1 July now lay with the BEF. Haig attempted in vain to postpone the start of the offensive to mid-August so as to bring up reinforcements and additional artillery, but Joffre insisted on Haig keeping the agreed date because of the dangerous situation in which the French Army found itself at Verdun. On 23 June, German forces 78,000-strong made their (final) major assault north-east of the city of Verdun.

The German military leaders had been expecting for some time a large Allied Entlastungsangriff (‘relieving attack’ to use the term coined by the Chief of the General Staff, Falkenhayn) in the Somme region. That the attack was actually ‘desired’, as Falkenhayn wrote in his memoirs, ‘is to be doubted having regard to the situation at Verdun and on the Russian front.’3 Whereas the German armies in 1916 at Verdun and Galicia (the Brussilow Offensive) had no lack of heavy guns and ammunition, and bomber and reconnaissance aircraft were used regularly in combat, ‘they were wished for on the Somme with a thousand curses’, the Great War chronicler Stegmann3 wrote bitterly in 1921. General von Below, facing the Allied offensive, had asked in vain for 2. Army to be strengthened, and made repeated requests ‘for reserves, artillery and aircraft.’4 Falkenhayn awarded absolute priority to the attack on Verdun, however, and more importantly underestimated the British resolve to make the great gamble in northern France in the summer of 1916.

The Battle

The British and French opened the Battle of the Somme on 24 June with a preparatory barrage. The opening phase began with British light field howitzers bombarding the German wire defences and surface trenches. Two days later an incesssant, massive barrage by the entire artillery began along the central front line north and south of the road from Albert to Bapaume. For over a week 1,537 guns fired more than 1.5 million shells at the German trenches. At some sectors (Fricourt) the British used small quantities of poison gas and phosphorous as an accelerant, 5 but the effect of the bombardment as a whole fell short of the expectations of the British and French Chiefs of Staff, and the fears of the Germans. The British in particular were short of heavy artillery – their 467 guns were distributed rather sparsely along the twenty kilometres of attack front. Heavy rain and poor visibility had an additional negative effect on gunnery accuracy and prevented complete destruction of the German infantry and communications trenches and above all the very solid, partially concrete-built or reinforced bunker dug-outs.

The poor ‘softening up’ effort by the artillery and unfavourable weather were not the only factors to bring the success of the Allied offensive on the Somme into question, for the operational and tactical ideas of the two British generals commanding the operation were incompatible. While Haig, C-in-C of the BEF, had planned a rapid push ‘to the third line’ of enemy trenches, and so roll up the system, allowing a general breakout northwards, General Henry Rawlinson, C-in-C 4th Army, which carried the main weight of the attack, had initially only very limited goals. Rawlinson, advocate of a tactic known as ‘bite and hold’, aimed to make the infantry advance dependent on the penetrative success of the artillery: he was thinking of concentrated attacks by ground troops with the artillery following later if necessary.6 The result was a fatal compromise because Haig lacked authority over Rawlinson, Allenby (3rd Army) and Gough (Reserve Army) subordinated to him on the Somme.

Convinced that the enemy positions and machine-gun posts had been adequately softened up by the week-long bombardment, on the morning of 1 July British and French infantry units stormed the German trenches. 1 July 1916, officially the first day of the 1916 Battle of the Somme, became the bloodiest day in British military history. The BEF lost 57,470 men, of whom 19,240 were killed, the remainder wounded, prisoner or missing.7 The losses were particularly high on the left flank where VIII Corps, in its attack on Serre and Beaumont-Hamel, ran into the forward German line. 36th Ulster Division, later famed for its bravery, took the heavily fortified ‘Swabian Fort’ at Thiepval but was forced to withdraw after losing contact with neighbouring divisions.

The attack on the right flank, where units of the 4th Army achieved all targets set for the day (Mametz, Montauban) was more successful. The older generation of British military historians blamed Haig for the catastrophe, principally for his untimely operational concept and his ‘Mass and Morale’ fixation (John M. Bourne). The British media retain this negative impression of Haig. In November 1998 the Daily Express branded him ‘the man who led millions to their deaths.’ Other historians prefer to find an explanation for the disaster of the first day in the huge numbers of often raw soldiers (Kitchener’s Army) being thrown into the fray direct from training. The popular BBC production of 1999 ‘The Great War’ considered that a contributory factor had been the manner in which the infantry divisions crossed No Man’s Land, marching upright and in closed ranks into the German machine-gun fire.

The Australian military historians Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson pointed out in a recent book involving very detailed research into the Battle of the Somme that probably only twelve (but possibly another five) of the eighty British battalions which ‘went over the top’ left their trenchs to converge on the enemy positions in a straight line and at a common tempo.8 The other battalions came up to the German front under cover of darkness, or the men had more or less spontaneously re-formed in No Man’s Land into small fighting groups practising various tactics of attack. Even that had served the British infantry poorly, however. Whenever German machine gunners had been able to fire directly into the attacking infantry the latter had been exposed to a lethal hail of bullets, and mortars, no matter how they advanced. The decisive error of the British and therefore the cause of the enormous losses on the Somme on 1 July was accordingly an inadequate preparatory artillery bombardment for the ground troops to follow, and the inaccurate and ineffective fire directed towards the German machine gun and gun emplacements, which were able to put up a barrier of preventive fire of unexpected scale when the time came.

That such an attack could be prepared and carried through successfully was proven on 1 July by the French south of the Somme. Supported by the 688 guns of their heavy artillery and attacking only along a sector fifteen kilometres in length, Fayolle’s 6th Army reached all its objectives (north of the Somme as far as Hardecourt and south to Fay). 1.Colonial Corps reached the main German defensive line and won ground temporarily. Over the next few days French troops consolidated their territorial gains and in some places even managed to push the front line five kilometres eastwards towards Péronne. Even the French were far from achieving the desired breakthrough on the Somme, however. On 12 July, General Fayolle, C-in-C 6th Army, noted in his diary: ‘This battle never had a goal. We cannot speak of a breakthrough. And if there is no breakthrough, what was the point of the battle?’9

Despite the disproportionately high losses and the comparatively minor gains in territory neither the French nor British High Commands considered calling off the offensive even though the two Chiefs of Staff, Joffre and Haig, were increasingly at odds regarding the future direction and objectives of the ongoing operation. Soon there could be no talk of coordinated proceedings: from now on British and French conducted their respective attacks without agreeing the operational and tactical details with each other beforehand. Instead of large-scale offensives and encirclements of the enemy, the French and British forces became increasingly committed to minor battles with high losses to win every elevation, every scrap of woodland and every village. After the introductory attacks of both armies on a broad front, this now converted into the second phase of the battle. It lasted from mid-July to mid-September 1916.

Later, military historians would describe the bloody fighting conducted by enormous masses of men and materials as ‘wastage battles’ (batailles d’usure).10 An example of this was the capture of Pozières and the ruins of a mill near the village by I.Anzac Corps between 23 July and 5 August. The ‘victory’ on the communications highway between Albert and Bapaume was bought for the price of a third (about 23,000 men) of the three Australian divisions in this sector. The advantage to the Allies was an important exit trench in the central battle area. The costly Anzac raid on Pozières – together with the disaster at Gallipoli – later became the foundations of the road to Australian independence from Great Britain.

The German defenders on the Somme were clearly inferior to the Allies in numbers and weaponry. By the end of August, the British had sixty-two, and the French forty-four divisions, a total of 106 infantry divisions against fifty-seven and a half German, and the head count in the latter was not only considerably less, but some German divisions in the field were counted several times over.11 The more than 1,500 guns of the Allied armies at the beginning of the battle were opposed by 598 light and 246 heavy artillery pieces. Still greater was the Allied superiority in aircraft at reconnaissance units (aircraft and balloons), and also in fighters and bombers. Reich archive historians calculated this initial disparity at 3:1 in favour of the British and French side.12

The German High Command reacted to the Allied offensive with a comprehensive rearrangement of their units on the Somme (19 July). From now on von Below commanded exclusively the new 1. Army operating north of the river, General Max von Gallwitz led 2. Army on the southern sector of the front with overall control of both armies. This was only a provisional measure, for on 28 July the Somme armies (together with 6.Army stationed between Lille and Arras and led by Generaloberst Freiherr von Falkenhausen) were placed under Army Group Kronprinz Rupprecht von Bayern. This was a desperately urgent solution to relieve the ‘worn out divisions’ by fresh units on a broader ground base. None of these ‘new’ infantry divisions – according to the declared targets – was henceforth to spend more than fourteen days’ fighting, while artillery units, of which as a rule lesser demands were made, would be exchanged after every four weeks.

The wide-reaching shuffling and re-groupings of the German armies in the west shortly before the dismissal of Falkenhayn and the setting up of 3.OHL under Hindenburg and Ludendorff (29 July) reflect the great extent of uncertainty in the German military High Command, and also the gradual realization of the true enormity of the battlefield in the Somme region.

On 15 September, tanks made their debut in warfare for the first time. The thirty-six (of forty-nine deployed) British Type Mark I tanks which attacked German positions north-east of Pozières were not very successful, but did cause considerable consternation amongst German infantry, which had nothing similar. In the offensive mid-month, and in a major attack on 25 September, units of the French 6th Army were again involved, and British and French forces penetrated the front at Thiepval, Martinpuich, Combles, Rancourt, Cléry-sur-Somme, Barleux and Chilly in the south to push the German front a few kilometres further eastwards, but the hoped-for major breach of the front eluded them.

The removal from the line of exhausted units, eventually practised on the grand scale, constant replenishment of the initially far too small supply of ammunition and the building up of previously weak air reconnaissance and bomber groups enabled the Germans to compensate gradually for their former inferiority. The formation of fighter-aircraft units (Jagdstaffeln) expressly for the purpose made it possible by mid-September to put an end to the air superiority of the Allies at the Somme. The twelve warplanes, single-seater fighters of Hauptmann Oswald Boelcke’s Jasta 2, won almost legendary fame. Boelcke alone shot down forty enemy aircraft, twenty of them over the Somme. He was decorated with the Pour le Mérite and died a hero’s death at the end of October 1916 near Bapaume.

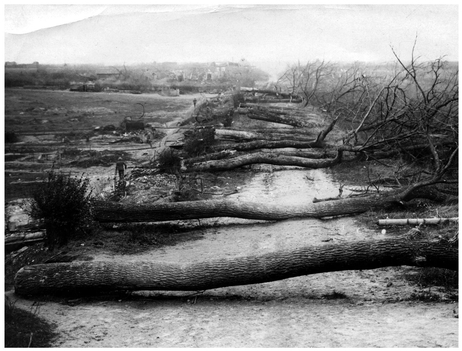

The third and last phase of the Battle of the Somme began at the end of September 1916, breaking down into countless minor battles. Many of the local attacks by the Allies failed (especially the British attack on the Warlencourt height, and the French in the St Pierre-Vaast Wood), or had only limited success. From mid-October the autumn weather brought a change for the worse as persistent rain transformed the battlefield into ‘a landscape of primaeval mud’ (Ernst Jünger), a giant sewer in which men, horses and vehicles stuck fast and could hardly move forward. ‘Everywhere deep shell craters, most filled to the brim with water. At their rims one edges through the mud. The trunks of trees, fallen and ragged with shrapnel, over which one has to climb. A ghastly assortment of about six corpses, cut to pieces, covered in blood and mud, one with half its head missing: a little further on a blown-off leg, a couple of bodies so forced together that below the layer of mud the individual corpses cannot be distinguished,’ wrote regimental physician Hugo Natt in November 1916.13

In mid-November 1916, after a temporary improvement in the weather, the last major attack by the British 5th Army (until 1 November the Reserve Army) under General Gough along the Ancre river was considered a disappointment, despite the capture by 51st Scottish Highland Division of Beaumont-Hamel which had been so hard-fought previously on 1 July. The French, who in September had reached Bouchavesnes north of Péronne with heavy losses – their farthest penetration eastwards of the German line, were little able to consolidate their territorial gains in this locality, and made no breakthrough.

The towns of Bapaume and Péronne, the hard-fought objectives of the French and British attacks, remained securely in German hands. The Battle of the Somme ‘slowly burned out’, as a popular German military chronicler described it.14 Neither side achieved any noteworthy success: new military technology was tried out by both sides, new operational strategies and tactics were developed or rejected. Both sides claimed to emerge from the battle the victor – the price which they paid to do so was fearsome.

The Balance Sheet

The 1916 Battle of the Somme was far and away the bloodiest battle of the Great War. Between 24 June (commencement of the artillery bombardment) and 25 November (provisional end to the fighting), the British lost a total of 419,654 men dead, wounded, prisoner or missing, the French 204,353 and the Germans about 465,000.15 Thus the Allies’ losses were substantially higher than those of the German defenders. The British losses exceeded the worst estimates of their military leaders. The Somme destroyed, in the long term, the fighting ability of twenty-five British divisions;16 put another way, every second British soldier who fought on the Somme was either so seriously wounded as to be unfit for future military service or failed to return at all.

For the Germans, the Battle of the Somme represented an enormous ‘bloodletting’ from which the Western Army, already weakened in the offensive before Verdun, would not recover. The Reich archive military historians summarized the Somme losses later: ‘The existing old nucleus of German infantry trained in peacetime bled to death on this battlefield.’17 To replace these experienced soldiers, amongst whom were numerous senior NCOs, there now arrived fresh and often inadequately trained recruits, whose chances of survival were accordingly that much slimmer. Responsibility for the extremely high losses lay not least with the German High Command, which at the beginning of the Battle of the Somme had insisted that the forward trenches be held at all costs. The German front line, as a rule heavily manned, could only be vacated voluntarily with the express authority of High Command.18 This restricted to a major extent, if it did not actually render impossible, the mobility of the German infantry in the front line.

In view of the immense losses caused by the long artillery bombardment and the increasing refusal of many German soldiers to fight only ‘in line’, a new tactical concept, the so-called ‘Stormtroop tactic’ was introduced on the Somme. Developed by Ludendorff before he entered 3.OHL, and officially accepted by 2. Army at the end of August, the tactic involved small operational units set up ad hoc at regimental level and commanded by officers with good front experience. By this means did the German infantry on the Somme, despite the oppressive Allied superiority in artillery, increase its fighting prowess if only temporarily. The experience of service in small elite groups led by a proven front-line warrior created a new kind of soldier, converted by Ernst Jünger into an enduring monument in his memoir In Stahlgewittern based on his own experience of the Somme. Jünger sketched a mythically exaggerated, stoic warrior and ‘true hero’ of the Great War no longer susceptible to the horror and suffering of the battle. This anti-bourgeois, ultra-militaristic type of soldier was found in the 1920s literature and the ideology of the military nationalism of the Weimar Republic before ‘Steel-helmet Face’ (Gerd Krumeich) came to embrace the experience of ‘total battle.’ By extension the SS-man was its most radical and inhuman expression.

In a certain way the myth of the heroic ‘Somme Warrior’ of post-war Germany corresponds to the ‘heroic image of the warrior’ current even today in British military history writing, more precisely the British infantryman whose skill, courage and readiness to sacrifice himself were qualities evident on the Somme.19 Yet the ‘first day’ of the battle, 1 July 1916, showed that those soldierly virtues could not determine the outcome of an attack. The Great War was an industrialized civil war whose material battles in Flanders, at Verdun or on the Somme were fashioned and decided principally by mass-produced large-calibre guns and the new possibilities of technology such as warplanes. This fact was first recognized by those who fought there. At the beginning of October 1916, Vizefeldwebel Hugo Frick, attached to a reserve division on the Somme, wrote to his mother in Germany: ‘It is no longer a war, but mutual destruction by the power of technology. What hope has the soft human body against that?’20

Otto Maute (1896 – 1963), Driver, Machine-Gun Company, Inf.Regt 180/Reserve-Div.26.

In Civilian Life a Factory Worker.

Letters to His Family at Tailfingen/Balingen

23 June 1916 (Warlencourt)

Am writing to you again after having my baptism of fire so to speak. With three drivers we had to take two four-horse waggons at ten in the evening after 1. and 2. platoons riflemen arrived in trenches. From Warlencourt, as the village is called, we rode via Le Sers, Courcelette to the positions and stopped at the running trench of the third line to unload guns and ammunition. About then the British fired some rocket flares, after which the artillery of both sides opened up. For the first time I heard the whistle of the shells which hit nearby. We came under fire because we were in the vicinity of the German artillery position. Naturally it was impossible to quieten the horses. As soon as we had finished unloading the waggons I headed back. We got to Warlencourt at about 0330.

I will tell you some things about the railway journey. I have written to you every time we were at a new position.( . . . ) In Bapaume we de-trained, you can find the town on the map. From Bapaume it was a one-hour drive here. Once we settled in, everyone started to write. On Tuesday we were inspected at Miraumont by the divisional commander Generalleutnant Freiherr von Soden. On Wednesday we were inspected by the regimental commander. His name is Oberstleutnant Fischer. Yesterday we did not have much to do except look after our horses. Then at ten in the evening we went to the front. Today I prefer not to go out because the British are shelling like mad. Otherwise it is not so bad here, better than Müsingen. The food is adequate, in the field one gets a loaf of bread every second day. Write soon telling me what it is like at home. How is the farm, have you begun with the hay yet? Behind the front we are reaping everything. Arras is not far from here. Now you know where I am. Write soon and send something for my thirst.

25 June 1916 (Warlencourt)

Today is my first Sunday in enemy territory. One notices nothing strange about it. Just as we arrived they said the British are going to open an offensive and this seems to be starting. Since yesterday morning their guns are firing like I never heard before, it is a proper bombardment. Yesterday evening we had to go with three four-horse waggons to the trenches but got only as far as Pozières, where we were ordered to turn back because the approach road was under heavy fire. When we got back we could not unharness the teams, we had to stay at alarm-readiness. All the others had already harnessed up. We could not sleep for all the cannon fire going on. This morning we learned that the village of Miraumont is being evacuated. This is only half an hour between us and the front. Naturally we have packed everything so that if anything happens all we have to do is harness up and attach the team. This artillery barrage is hitting all the trenches. Naturally our guns reply, last evening one ammunition column after another went to the front positions. It is not impossible that the British will penetrate our front line and we will have to move out. Things with us are so different from yourselves at home, where everybody can take a Sunday stroll as if there were no war. Here nobody can leave the farm. Our Regt.180 is with Reserve-Regt.119, which has many Tailfinger people such as Scharr, Rieper, Eppler von Truchtelfingen ( . . . ) There are almost no civilians left in our village, on the farm where we are is only one woman whose husband is a soldier, and her fourteen-year-old son. ( . . . )

2 July 1916 Warlencourt

Yesterday was hot. The artillery fire which started on Saturday last week and especially at night was incessant. It stopped suddenly at midday yesterday. Then came the long-expected British attack. They attacked the front line of our division directly and broke through at Regt. 99. They got to our artillery positions. Then 10.Bavarian Inf.Div. was thrown in. In the counter-attack our people ejected the British from our trenches and then took the first British trench. While this was going on it remained quite quiet except that the ammunition columns drove like the furies. Then the wounded came in, the lightly wounded walked, the serious cases were on waggons or in ambulances. At midday we harnessed up our horses, then I had to go to Bapaume for ammunition. I drove like the wind. The British fired over us into Bapaume. They left the Bapaume-Albert road untouched, but we were showered by flying fragments the size of your fist, and it made us think because they landed only two to three metres away. What would it be like to receive a direct hit from a ship’s thirty-cm gun? The ammunition then had to be taken to the trenches, I did not have to go because I had fetched it.

According to the wounded, our regiment had heavy losses in the attack, but Regt.99 came off worse, they say fifty per cent. During the night the shelling resumed. We kept the horses harnessed up all night and had a good night’s sleep alongside them. This morning all the windows of the house facing the lower stall were shattered by splinters, there were a lot in the farmyard. Later when it quietened down we unharnessed and cleaned the horses, but harnessed them up again at midday, as they are now.

During the week, four of the villages ahead of us were evacuated. They were firing into them with phosphorous shells. The night before last Miraumont was burning brightly throughout the night when I had patrol. At home you simply have no idea of what war is like. This evening we have packed everything in case we have to leave as eight days ago. British prisoners brought in today are the first I have seen. Today an aircraft crashed in our neighbourhood. When you write to me you must not put the village name or I will be in hot water. I really should not have written this. I am not, as I wrote you last time, near Arras, but Albert. That is about ten kilometres from here. The local village commandant is also named Maute. He is a junior lieutenant and the son of a factory owner from Spaichingen. Father, if you know him, please let me know. Despite everything all is well with me, we have food so that I have never eaten so much meat, if this were Germany I would not want to go home( . . . ).

6 July 1916 Warlencourt

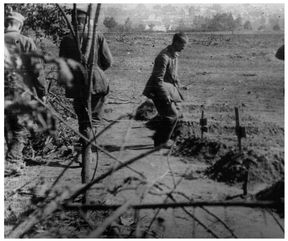

I also have to tell you not to put Northern France or Warlencourt on the envelope for it is forbidden to write where one is. You also have to advise the Post Office that it has to be left off. The service office told me that the village name is unnecessary and forbidden. I will receive everything, just write road and street number. Yesterday I ate in the forwardmost trenches. We took provisions to Courcelette, and then we had to take them to the running trench, two hours away. You have no idea what that means, the trench was so full of water it reached my trouser pockets. I had to drag my boots through it, it is a pure quagmire. A farm had been completely levelled by the shelling, the trench was obliterated. We received artillery fire along this 500-metre-long stretch. The air pressure of the shells as they exploded tossed us each time on our backs to the floor. One after another we jumped below and were sweating so much that it trickled down our legs. Suddenly a shell whistled over and we thought we had breathed our last, luckily it was a dud. It bored into the ground about five to six steps away. After that we went into a dug-out to rest. Afterwards we made our way through the trench. Where the trench had collapsed under the shelling we had to run because the British had the gaps under MG fire. Finally we reached the kitchen dug-out where we handed over the things. We stayed there thirty minutes and looked at the British trenches. Then we went back, and since the artillery was silent we left the trench, where you could easily drown, when we were half an hour from the front and we crossed open country. There I saw another corpse. We got back dog-tired at six. I had to change completely, my boots were full of mud. We had to wash trousers, socks, everything. You can see that it is often difficult but we also have nice days like today. Last eveing everybody on provisions transport duty had a piece of Swiss cheese and meat for supper. Although it is very dangerous, it is not so bad in the field. I am therefore still happy and remain healthy( . . . ). I do not need money, I have more than I ever had in civilian life.

1 August 1916 (Grévillers)

Written on first anniversary of my mobilization ( . . . ) Every second day everybody has to ride to the trenches. Each time we use two four-horse and one or two two-horse waggons. Then we have to make from here via Irles and Miraumont to Grandcourt where there is a field-railway station, and we have to go to that station to load up: hand grenades, wood for dug-outs and barbed wire. Then we go to the trenches and make the trip two or three times. The road there is naturally not even, just rough track made by lots of traffic and full of shell holes, and because we go by night we have to keep a sharp lookout. When we get to the destination we unload as quickly as possible because this location and the road beyond it are heavily bombarded. When I was there the last time at Grandcourt, two waggons ahead of me a shell hit an ammunition waggon which burnt out with the horses and drivers. Few splinters reached us. In that we had more luck than we can understand. We never get back until six in the morning, always covered in dust. It is damn hot. Yesterday and today aircraft bombed Grévillers, today four men were killed and thirty wounded by bombs. One of our drivers was wounded so that now we have lost three, two being struck by horses and this one. Otherwise I am still enjoying it. Tomorrow we go to the provisions yard, and at midday we will go with the horses to pasture and stay there.

7 August 1916 (Favreuil)

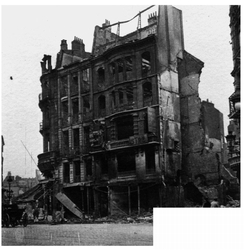

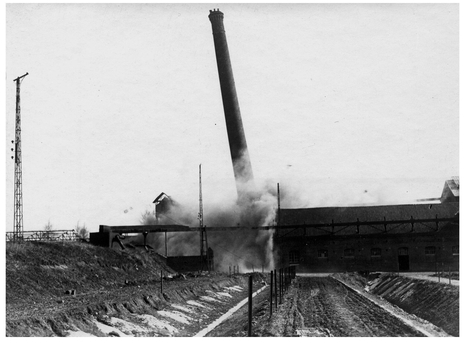

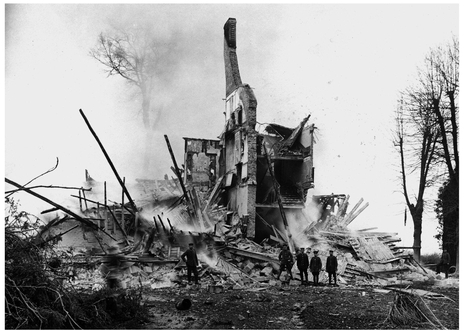

Scarcely had I written to you on the 3rd and handed it in, than a bomber squadron flew over our village Grévillers and dropped one after another ten bombs, killing five and wounding fifteen, also eight horses lay wounded in the street. Next day at the same time they came again and dropped bombs. This time one of our drivers was wounded in the hands and feet by splinters. The same day (4th) at 0730 eight shells came over one after the other and all hit in and around the church. The church clock stopped at the precise moment, and half the tower collapsed. Now there was a withdrawal. You cannot imagine it. The whole village was stuffed with the military. Ambulances were driving around as if demented. First we got the horses out of course. Quite a lot had been killed or injured, also from blocks of stones or beams. We received the order to harness up. We left at 0100 after everything was packed and loaded on the waggons. We went now to some villages further back and passed through Biefvillers, Favreuil to Beugnâtre. There we stayed on 5th and 6th. Then we came forward a little to Favreuil where we are now, but we are in barns. Naturally we have a longer journey to the front because it is much further, well beyond Bapaume. But it is good we left Grévillers because meanwhile the British shelled it to a ruin. Today we had the funeral of two fallen comrades from our company. We brought them from the front, and today they were buried in the local cemetery. Both were killed by a shell. Otherwise I have no news.( . . . )

10 August 1916 (Favreuil)

( . . . ) I have to tell you that I was nearly killed last night. As every evening we left here (Favreuil) with two four-horse waggons to collect materials from Grandcourt station for the trenches and had arrived, and were about 400 metres out of St Pierre-Divion where we had to go. We had loaded iron and steel, naturally it weighed a lot, suddenly shrapnel hit amongst us. At once all four horses went down, my lead-rider and I were hurled into the horses, I got tangled up and the shrapnel balls kept coming while I was trying to get clear. Then we two drivers and the guard who was with us slipped under the waggon, and then three or more pieces of shrapnel fell amongst our nags. My saddle-horse was dead immediately, the other three survived it but all had their hooves sheered off. I got off lightly with a minor wound when a stone hit me in the chest. My lead-rider had a gash in the forehead from shrapnel amd more gashes in a foot, the guard has his face and left arm peppered by shrapnel balls, the NCO with us applied a field dressing to the other driver, and then they shelled so abominably that we could not get away. We remained ninety minutes with the waggon, I went over to the horses several times, they were trying to stand up but had no hooves. Once it fell quieter I went into St.Pierre-Divion to fetch a rifle, when I came back the leading saddle-horse was also dead, and the NCO with us then shot the other two horses. Then we returned to Grandcourt where we reported to the Feldwebel at the pioneer park, who wrote out a report, our names, everything. We slept until about five in the accommodation room, then we two went to Miraumont where an ammunition waggon from our company brought us back. That happened about 1230. As I wrote before, the highway between Grandcourt and St Pierre-Divion is dangerous because the British trenches can observe it and they fire star shell to light it up bright as day.

You should have seen their faces when we got back and told them how the other four-horse waggon which we had was no longer with us, and about the baggage waggon. The Feldwebel had been told that all four horses were dead and the drivers (therefore we two) wounded, which was true. I got a stone or splinter in the chest, a mere trifle, my lead-driver is wounded in the head and feet. I have no more horses and those were good. I have been to the front often enough, and nothing happened before, but you cannot win them all. Ahead of our front it is always hot, the name Pozières, lying before us on the Bapaume-Albert road, is mentioned almost daily in the Daily Report. The British offensive has brought them well forward, and now they can destroy all the villages behind the front, that is why we are so far back. Warlencourt, where we were first, had been reduced to ruins, and we were forced to evacuate Grévillers on 5th because they were shelling it. Other than that all I know is that there are so many flies in France that when it is hot by day there is nothing one can do to stop them eating you. Since I have been in the field it has almost never rained, the roads are so dusty that horse, man and waggon are covered in dust ( . . . )

18 August 1916 (Favreuil)

( . . . ) Driver Renz who fell last night will be buried tomorrow. His whole body is covered in balls of shrapnel. You must therefore not be anxious, if one gets hit, then in God’s name.

27 August 1916 (Favreuil)

If you have a shirt which weighs less than one pound send me one. We all have lice and when we wash the old shirts they come apart. Occasionally we all get the shits which is bad. Otherwise I am well and in good spirits.

1 September 1916 (Favreuil)

The region where we are, all France, is very fruitful. Oats are abundant. One sees what it means to have the war on one’s doorstep, the civilian prisoners are now all farm labourers. ( . . . ) I enjoy it so much better than in the garrison, in the field it is not so regimented. It remains lively though, enemy aircraft drop bombs in our neighbourhood daily, or one or two are shot down in aerial fighting with a German. My comrade Gottlieb is now also in the district but further south, he wrote me that it is a different kind of artillery bombardment here on the Somme than at Ypres, where he was before.

15 September 1916 Favreuil

The day before yesterday I was at the trenches, this time it was windy again. On the way out between Miraumont and Grandcourt a shrapnel bomb exploded directly above a waggon, I was hit by two shrapnel balls in the chest, not hurt, naturally I galloped away from this dangerous place. When we were driving later from Grandcourt to the front, towards Thiepval, the British fired gas shells. Despite my gas mask I got a mouthful. On the way home I had a headache from the inhaled gas and spent a long time vomiting (one says here ‘threw up like a palace dog’). I soon got better and my appetite returned. Last Sunday 10th at 0130 we were awakened when an enemy aircraft used the fine moonlit night to bomb our village, and hit ammuniton waggons. Eight of these exploded with a terrible noise. Little damage was caused, two men were wounded, three horses and five cows killed.

Karl Eiser, Sergeant, Reserve Feld-Art.Regt 29/Reserve.Div.28

Source BA/MA Freiburg, PH 12 II/57

Report (Written in August 1916)

From my War Diary respecting the great fighting at the outbreak of the Battle of the Somme from 24 June to 4 July 1916, which I experienced as an artilleryman on the Staff of I Detachment, Reserve Field-Artillery Regiment 29!

The task is difficult, and I do not know if and to what extent I can do it: I will try to compose from my meagre notes what I remember of those days and what our battery, our I Abteilung, Reserve Field Artillery Regiment 29 achieved by almost superhuman effort and offering up the last reserves of nervous energy.

We are in the Champagne region near the ruined village of Fontaine/Dormoise where we first understood correctly the full horror of the past days and for the first time could sketch an outline of our many experiences. Although the battle has already raged longer than a full month with the greatest possible consumption and use of enormous quantities of war materials and battlefield gases and the British have succeeded in breaking through our lines, their great planned breakout failed due to the iron will – after seven days bombardment and destructive artillery fire – of small fighting groups, lacking any reinforcements worth mentioning, who held off the powerful masses of enemy infantry and brought them to a temporary standstill. The great British Breakthrough Offensive of the Somme Battle failed!

‘Battle of the Somme.’ What a sad ring this phrase has when spoken by a German tongue: of inexpressible suffering, of unlimited readiness for sacrifice. There in northern France, our comrades of 28th Reserve-Div. went to their graves in their thousands. Most of them sons of our Baden homeland, many hundreds of them torn apart by shells, ploughed deeply under on heights and in valleys, while others rest in many war cemeteries, and finally the least number who receive their death honours and rest in the military cemeteries of the German homeland. In respect we bow our heads at the scale of the sacrifice. The name Battle of the Somme is holy to all of the 28. Reserve.Div who survived.

It was the beginning of May 1916 when the British facing our sector became increasingly restless, and one operation followed another. In the earlier firing to unsettle us, our Staff MO at Pozières was killed, while Major Radeck and Oberleutnant Weissmann, previously active with our I.Abtg. were wounded. By then almost every battery had lost gunners and some spotters to enemy fire. The British became ever more active, but we had no idea what they were up to: nobody suspected what was in the wind. Hill 110 at Fricourt was often subjected to furious shelling, and the continuous trenches and long stretches of the main front were levelled.

Life at our Fricourt West observation post was often soured on excursions to collect food. For me today it remains an incomprehensible mystery what the purpose was of having our artillery spotters there, for it was certain that the main trench could not hold out against even a minor attack and we would all have to surrender or be wiped out. By mid-May nearly all communications trenches on Hill 110 had been bombarded and levelled. The forward part of the traverse trench leading to the Hill 110 trenches had been shelled beyond recognition. Usually around midday the British would fire large-calibre shells and heavy mortars at the trenches.

On 3 or 4 June we sent out patrols, and on 5 June the British did the same, with the objective of taking prisoners in order to assess the disposition of enemy forces. Increased alertness was required of our observers since, contrary to the usual practice, the enemy artillery fire did not diminish once his patrols returned, but often continued wildly for whole days and nights.

In mid-June it was quieter, the lull before the storm. From 20 May onwards there was great activity behind the British lines. From our observation point on the Contalmaison Tower we watched endless columns of lorries making the jouney between Bray-sur-Somme and Albert every day. These convoys often consisted of 100 lorries. We frequently saw great artillery convoys, so long that it would take three hours for each to pass a given point. A standard gauge railway track was laid by the British between Fricourt and Bécourt using German PoW labour. At the eighty-metre mark on the Bray-Albert road the British set up a large airfield. Their infantry activity was very noticeable by the number of patrols and armed reconnaissance sorties they made, and their many mortars. All our reports were fed by I.Abtg. to Division.

At 0300 on Friday 23 June a furious bombardment began, shells exploded along our entire divisional sector, on our trench lines, various lengths as well as the single ones, the whole defensive line at Fricourt, Lehmgruben (clay-mining) Hill to the Lehmsacke (clay bog) lay under heavy shellfire. Our landline to the Fricourt West observation post was cut, even though it had been buried one metre deep. At midday the heavy bombardment died away and quietened – Mars.

At 0130 on Saturday 24 June our whole line, in a semi-circle around us from the enemy side, was lit up as innumerable lightning flashes soared over, a hissing and howling, gasping, splintering and exploding – all this filled the air. I was on watch on the Contalmaison Tower, I shouted into the telephone, I could not hear myself, I had to assume they had understood in the mansion cellar. A few moments later Hauptmann Kipling, commander of 7.Howitzer Battery, stood beside me. It was a fine sight, this flashing and lightning of the enemy artillery. The British were pouring down heavy fire mainly on the territory to the rear, our artillery positions, so far as they knew them, and all known observation points, access roads and villages far enough back that until now they had been spared attention. The trenches received little fire. It was frightening, all that noise of exploding shells, an artillery bombardment involving all calibres and kinds of munitions, such as I had never known in two years of warfare, roared and hissed over and around us far and near. At sunrise at crossroads and on the access roads the little clouds of shrapnel balls came flying, in between the impact of heavy shells sprayed high into the air. The mansion received heavy fire from various calibres, several direct hits shook the building, a red cloud of disintegrating brickwork hindered visibility, the shells howled overhead, landing on the outskirts of Pozières village, hiding the whole locality in smoke and fumes. Almost at the same time huge explosions of heavy shells reduced to rubble the last standing ruins of the houses in our village.

The evening of 30 June brought no change: smoke, gas, foul fumes. The British continued shelling our village until late at night, also the outskirts where 911 platoon/1.Battalion was stationed, with shells armed with a delay fuse, in the dug-out one felt the tremendous jolt and tremor of the ‘moling’ shells with which they were showering the village. Heavy shells howled and wobbled high overhead into our Etappe right through the night. Over the entire rearward area, as we were now becoming used to it, the access roads were now being subjected to bombardment every night.

The morning of 1 July dawned. Towards 0330 I crawled out of our dug-out to orient the fall of enemy shelling. The depression between Contalmaison and Edinger village (position between Contalmaison and Fricourt) was shelled with a gas which smelled of bitter almonds, presumably prussic acid. A milky white, lazy wall drifted slowly towards our village. Inf. Res. Regt.111 reported from Fricourt that the British had filled their trenches, it smelt of prussic acid everywhere: we knew that our gas masks offered no potection against it. From Pozières to the Fricourt depression everything was hidden by a white veil of gas. At daybreak Res.Grenadier-Regt. 110 reported from La Boisselle that the enemy had filled the trenches there, and 109 reported the same from Mametz. We awaited events in high tension. What would the day bring? Perhaps we would not survive it – many thought this. As the first rays of the sun gleamed white, the vile gas rose up and soon we were immersed in it. Visibility was down to ten metres. The barking of the enemy guns increased every second, hell roared up: but only for a short time!

Since Thursday 29 June on Hill 110 we had seen only smoke, fire and exploding shells, on the eastern side a series of explosions. They must have hit the arsenal for our mortars. With deep sadness we think of our infantry comrades in the trench: how many of the company would still be alive? How many men would a battalion or infantry regiment still have who were fit to fight? We knew that on Hill 110, our artillery comrades, our own trench, were in the greatest danger: or were perhaps already dead? Hill 110 observation point, the stone quarry, the work platform and Fricourt West were on the forward trench line and short in numbers. I knew that the observation point here was in the hands of one of our best lieutenants, who was no coward and would rather die than surrender. He was Lt Mayer with two NCOs, Hittler and Viehoff, and two telephonists, Enderle and Baumann. A light wind began to disperse the swathes of gas a little. Observation point Hill 110 and Fricourt requested urgent covering fire: for this sector we had only two batteries, with only a few serviceable guns: these were 2. and 7.Battery with light field howitzers. They opened fire immediately. From Fricourt to Mametz, and as far as La Boisselle, urgent covering fire was being requested, 1. and 3. Batteries were under rapid fire. All heavy batteries in the wood at Mametz were out of action either from direct hits or the gas attack. II.Abtg. could not be contacted in the gully of shells! As all of our batteries were capable of being reached quickly, equipped partially with new guns but not all yet installed, the sector was under a barrage of fire. The hell that roared up is beyond my powers of description, the British artillery fire was a true hurricane, our own guns were inaudible. All our artillery fired for a full hour then gradually the iron mouths of the guns fell silent as hit after hit knocked them out. A wild slipping through of message runners began, coming and going to and from our Abtg. Platoon 911 at the village entrance also received a direct hit, my comrades, I knew them all, were seriously wounded: Schrempf, Kappenberger, little Noe dead. All at once the frenzy of enemy artillery fire ceased, although the heavy shells from the long distance batteries howled and twisted on their way to the Etappe villages. The decisive moment for attacker and defender had arrived.

The British had blown open a sector one company’s breadth from Reserve Inf.Regt. 111 between the brickworks road at Fricourt and Bahngruben Hill. British assault troops followed up at once and poured into our trenches. At almost the same time the enemy broke through small parts of the infantry line along our whole divisional sector. Luckily the morning breeze had by now dispersed the major cloud of gas and the observation points had improved visibility. Before us lay Edinger village, not really a village but a well-fortified ready infantry emplacement. The main kitchen galleries of our infantry regiment, and pioneers, and all kinds of materials were there. The field railway ran here from Martinpuich and the Ganter Works. Between here and the ridge is the Totenwäldchen wood, a little north-west the Ferme Fricourt. About 500 metres to the west of our village beside the small wood and the known path through the depression was our 3.Battery Hauptmann Fröhlich, whose reckless spirit and black humour was well know to everybody: 200 metres to the south of him was a small artillery refuge called the Völkerbereitschaft. Our 1.Battery was strung out in three parts along the road from Contalmaison to Fricourt, two guns: platoon 911 on the outskirts of Contalmaison, one gun in the depression on the road to Fricourt and the other on the ridge, this was listed as a dummy gun but, in true fulfilment of duty to the last, by almost superhuman effort took part in the defence.

The morning breeze gradually swept the great swathes of gas from the foregoing terrain and our field of sight improved. Our divisional sector became noticeably quieter, almost frighteningly so. The British long-range guns alone continued firing on our rearward positions, the local British artillery had fallen silent.

It was 0800 on 1 July. In the Totenwäldchen Wood two MGs were hammering, a long drawn out fire began, a burst of fire clattered into our village. Finally we saw the British assault troops, wearing white recognition patches on their backs, appear on the Totenwäldchen and Ferme Fricourt: therefore they had made major inroads into our infantry line. They stormed No.1 gun, the dummy gun of 1.Battery, when it did not fire they ran for No.2 gun at the officers’ dug-out in the depression on the road to Fricourt. The other two guns of 911 platoon were not ready to fire. Message runners and despatch riders circulated from our Abtg. to batteries in all directions with the order to fire. Our good comrade gunner Schölch had to run the order to 911 platoon but was hit by infantry fire and fell on the road from our village. I made my way to 3.Battery over the grim cratered field, leaping from one shell-hole to the next.

No 3.Battery was to fire immediately on the Totenwäldchen, the brickworks and Fricourt station, where the British were arriving in battalion strength on the Contalmaison highway. I met Hauptmann Fröhlich by his wrecked guns. He looked pale and bleary-eyed, gave me a message for Abtg. that he had no serviceable guns, all had been destroyed by direct hits. 3.Battery position looked awful. The British had come to within 200 metres of the battery. At that moment the Völkerbereitschaft came to life. The artillery refuge had the construction company composed of clothing store men and parts of Reserve-Grenadier Regt.110. This company was swiftly in action and opened a furious rapid fire from thirty to fifty metres range forcing the British back to the Totenwäldchen Wood.

Unteroffizier Kruger’s dummy gun of 1.Battery, recaptured from the British, now opened fire on the retreating enemy, firing first numerous dummies and then at 100 – 200 metres range detonators into the British ranks, causing heavy losses. Finally No.2 gun in the depression began to fire, and Platoon 911’s No.4 gun was repaired and readied. These three guns fired first on the Totenwäldchen, then the western end of Fricourt, the cemetery and station, where the British was present in large numbers. The two guns were fired over sights or by eye. Each round was a hit. Cornered like mice before the cat, the British left the Totenwäldchen and fell back on Fricourt. The detonators of No.1 Battery reaped an appalling harvest amongst the British infantry. Now they held only a small length of trench in the third infantry line. There was bitter fighting near Mametz where our Grenadier-Reserve 109 engaged in hand-to-hand fighting and fought for every inch of the trench line. We also saw all of Group Reserve 109 go into British captivity. Our infantry advanced along the road from Contalmaison to Fricourt, some companies even came up from the recruit depot. For us artillerists it was heart-breaking to have no guns or reinforcements worth mentioning, but at least our division had warded off the breakthrough for today. Our batteries in the shrapnel depression were lost, the enemy got to 7.Battery, the light howitzers on the edge of the wood at Mametz.

From La Boisselle on our right flank we heard unceasingly the explosions of many hand grenades, but on 1 July the enemy gained little ground. It was almost amazing, guns of various batteries kept up rapid fire for hours, firing mainly long-shell fuses without opposition. Fearfully we awaited a fresh attack almost all day, but the British did not risk the opportunity, preferring instead to consolidate and dig in along the sections of trench line they had taken. We did not receive enemy artillery fire because the enemy did not know the disposition of his own troops. In our battery positions the empty casings were stacked higher than a man, whole mountains of empty shell baskets lay scattered around, with a couple of smart companies the British could could have got right through to Bapaume in the Etappe.

This was the picture of 1 July: ‘No significant reinforcements, no orders from above! Mametz and Montauban lost, held by British. Hill 110 near Fricourt likely to fall. Fricourt village still in German hands but surrounded. We have lost our right flank at La Boisselle. Our observation trench reports: Lt Mayer fell in the cratered field. Gunner Baumann fatally wounded, Unteroffizier Hittler and gunner Viethoff, telephonist Enderle captured.’

One shuddered to hear the words ‘No reinforcements!’ We were deeply disappointed: why had we been abandoned with no reinforcements or relief? Was that our reward for what we had given up and sacrificed? We could still hold the line with a little artillery reinforcement and a couple of fresh infantry regiments. Before us we had as good as no more infantry. The British rifle fire had now abated – were they exhausted or could we expect a new attack? We left the hour unused. In the Etappe the Staff drove off in their cars, overnight they shifted HQ and its complicated telephone system to the rear, the gentlemen fearing the breakthrough. That we learned, we who for eight days lay below death raging a thousand times around us. They left us alone. And why? On the late evening of 1 July a company of Landwehr Battalion fifty-five occupied our village (Contalmaison). Their officers had no maps and were clueless as to what was going on.

The three serviceable guns of 1.Battery was found on the night of 1 July and put behind the mansion gardens ready to fire from a half-built structure. That night many wounded of Reserve Inf.Regts.110 and 111 still able to drag themselves along came through on their way to the rear. They recounted the most appalling crimes committed by the British against their prisoners. We had to listen to the most terrible stories although we had no head for it. The British resumed their usual barrage to prevent traffic using the roads and access tracks, especially with sudden great bursts of firing. Our three guns behind the mansion had hardly fired a round before the British spotted their position and put them under heavy fire. On 2 July the British opened with rabid fire at our sector, but their fire was ragged . . . .

August Dänzer, President of Prince’s Chamber, Freiburg im Breisgau

DIARY

5 July 1916

Reports by the French state that especially south of the Somme they have made further progress, taking Estrées and Belly, after earlier capturing Assevillers, Feuillères and Flaucourt, and the British La Boisselle. It seems we are involved in the greatest battle in the history of the world, in the most critical period of the whole war, and if God grants us victory this time, peace will dawn.

18 July 1916

In the afternoon, short walk with Sondger in the Sternwald. From a letter sent to him by his brother von Hanauer with Reserve.Inf.Regt.110, I infer that the regiment was involved in the fighting against the British at La Boisselle. These British are reported to have shot dead German prisoners with their hands raised. The Germans are then said to have retaliated and shot 1,200 British whom they had surrounded.

Whole companies of Reserve-Regt.110 were wiped out, and the regiment is now in the Champagne to reform and re-equip( . . . ).

Hans Gareis, Vizefeldwebel, Bavarian Inf.Regt 16/Bavarian Inf.Div.10

Source: Kriegsarchiv Munich HS 2106

Report (Undated)

Experiences of the Somme Battle, 1916: Diary Notes

6 July 1916

Today I returned from leave to rejoin I Battalion/Inf.Regt.16. My battalion was on a ridge opposite Montauban. Towards 2200 I went up with the field kitchen: they handed out the rations on the Flers-Longueval road in a depression to the south of the village. Before we reached the location we came under shrapnel-shell fire. One horse of Field-Kitchen Company 1 was killed, one man was wounded. The running trench which we passed had been terribly shelled, the position looked as if it had been ploughed over, in the trenches only emergency galleries. The same night I took over my 1.Platoon/4.Company.

7 July 1916

The weather is dreadful, therefore lively enemy aircraft activity while we have no airplanes up. I lost another three men from my platoon today.

8 July 1916

Up to my ankles in water. On the road from Mametz towards Montauban and to the Mametz Wood with binoculars we saw British columns marching, preceded by their artillery. Our artillery did not fire. Twelve barrage balloons hung over the enemy trenches nearly all day. Towards evening we received heavy shellfire. A direct hit collapsed the right-side, heavily manned gallery entrance of the Company Commander’s room housing the Battalion Staff. Lts Rosenthal and Auer, and Unteroffizier Bucher were wounded, nine men, some the best in the company, killed. My platoon is now twenty-five men and four group leaders. My people sat in the underground gallery and prayed. When darkness fell we started digging out the dead: the sight was ghastly, the most terrible thing I have seen since 1914.

9 July 1916

During the night terrible artillery fire. While fetching rations the company lost another five men, three dead, two wounded. In the morning the weather finally cleared and there was lively aerial activity. In the afternoon another terrible artillery barrage with heavy shells. Longueval burning fiercely.

10 July 1916

In the morning I had a group go to Longueval for ammunition, before they reached the depot it blew up. We have no mining frames for shoring up and no prospect of relief, one has to keep moving everything around in order not to become apathetic.

11 July 1916

In the morning fifty replacements came up with Lt Wagner, married men amongst them with no experience of fighting. At midday four men of my platoon were buried alive by a direct hit, two men of the morning’s replacement were killed, one the father of four children. At night thank God we got the shoring-up frames.

12 July 1916

In the morning artillery fire as every day. In the afternoon the rear wall of the trench received a direct hit which collapsed the galleries. We were up to our knees in earth and had to struggle free. At night I got digging with everybody available. To protect the dug-outs at night we filled in the shell-holes above the galleries.

13 July 1916

Last night violent artillery barrage which went on all day. By evening the trench was a long series of shell-holes. In the early evening we received a report that the British are massing in the depression at Bazentin. The company sent a patrol to reconnoitre and they confirmed this.

14 July 1916

Towards 0300 we set up another mining frame in the gallery and I wanted to let my people rest, then came a rumour that ‘The British are attacking.’ In a trice the platoon was at the parapet, I distributed my people – not easy in the total darkness – the first flare rose and before us, barely 300 metres away, we saw the British advancing in large numbers towards our wire entanglements, steel helmet by steel helmet, an impressive sight. And now it started. A rage gripped us all, but also a feeling of joy to have the chance to avenge ourselves for what had gone before. I roared: Hurrah! and Fire! and knelt with the nearest people at the parapet to have a better field of fire. Others followed my example. So we received the enemy with rifle and MG fire interspersed with shouts of Hurrah! The British artillery fire rained down on our position, luckily on the empty support trenches, but showering us with splinters. That all remained unnoticed in our lust for battle. Even our young replacents left nothing to be desired. I detailed a few people as munitions runners and to gather up the rifles of the dead and wounded to exchange for our hot-barrelled ones. I had three rifles, one in use, two cooling. In the light of the starshells we watched as the British line began to thin down. Dawn was coming.

A British aircraft arrived and with admirable skill replied to our rifles with MG fire. Ahead of our line the attack had petered out, they lay in heaps in the wire. A few who showed signs of life were dragged into our trench. Some took refuge in shell craters, then turned and ran for the British line, and were shot down. A few hundred metres away they set up mortars and fired on the sectors of our No.1 and No.2 Companies. Our sector was spared. I shared my last pack of cigarettes amongst my brave people, they wanted to hug me, so great was the jubilation. We believed we had the right to be pleased.

When the first starshell burst we saw the rows and rows of British marching towards our position, weakly defended by tired troops: we feared the worst, but not one British soldier had come over the parapet, and now their front rank hung dead or wounded in the wire entanglements. That it might be different to our right and left did not occur to us as we celebrated our victory. After this short pause we all went back to the parapet except for a few people attending to the dead and wounded.

From the Company Commander, I learned that the Company had lost thirty men, No.2 and No.3 platoons had fared worse than mine. We covered the dead with tarpaulins as an emergency measure, there being no time to bury them: then, with my two most senior corporals, I turned to face No Man’s Land. We brought a British MG and numerous prisoners into the trench, including from No.2 platoon a wounded British colonel caught in the nearest barbed wire hedge, a smart man with a pleasant face. Soon it was completely light, and then I began to suspect the worst.

We could see without binoculars columns and columns of British marching along the highway to Longueval and nobody fired at them. This meant they must have broken through the line here. For us the range was too great and in any case we had no ammunition. I hurried to the Company Commander to report and found the Battalion Staff there as well. Major Wölfel, Oberleutnant Marschall, Lt Sässenberger and a couple of orderly officers met me in a shell-hole in front of the battalion post in the forward trench. I listened to the reports. The enemy had broken through on the left at No.3 Company and now held the outskirts of Longueval. No.2 Group to the right reported the enemy at Bazentin. The Regimental Staff, including the commander, Bedall, had been captured. We were therefore adrift: if we did not receive reinforcements from the rear, or they failed to pull us back, we were lost, for the battalion had been so weakened that it could not withstand an attack, and we were out of ammunition: in my entire platoon sector we did not have a single hand grenade between us. The depression to our rear lay under a furious artillery barrage, and a retreat by day with the remainder of the battalion was rejected by Major Wölfel and the other officers . . . .

Gustav Krauss, Unteroffizier, later Leutnant, Reserve.Inf.Regt.29/Inf.Brigade 80.

In Civilian Life a Bank Clerk at Heidelberg

Report (Undated)

Source: BAMA PH II/502: Photographs BfZ I AH52.

12 July 1916

In the evening we moved into Cartigny where we were billeted in a fine mansion. The rooms had none of their former elegance, only two-tier bunk beds or wood in which we slept on shavings.

13 July 1916

The place has a fine old church which I looked over. We counted eighteen French barrage balloons while we have only three (a French aircraft shot down five in flames). The railway station was plastered continuously with thirty-eight-cm shells. At night it is forbidden to show a light. There was a big artillery battle raging at the front which we watched from the roof of the mansion. It was a grandiose sight. Half left of the mansion was a twenty-one-cm mortar which the French were making efforts to wipe out. The firing continued throughout the night. We kept ourselves busy all the time and heard all kinds of rumours. We know we are not being invited to a party, but on the other hand we are hoping to be deployed soon so as to get away quicker. The worst is the waiting and uncertainty. In the evening we heard that it would begin during the night.

14 July 1916

Scarcely had we settled down for the night than we were awoken at 0100. Ahead we could hear the sounds of firing. We paraded, were issued with hand grenades and then marched down the wonderful highway towards Peronne, the night as black as pitch, only lit by the flares at the front. We turned off left to cross some fields. White strips of cloth on posts marked the route. On the way a comrade had a screaming fit. Soon we came to the banks of the Somme and crossed by means of a wooden bridge several hundred metres long erected by the pioneers and which is frequently fired upon – no casualties.

In a hamlet Chapelette we dug small holes for protection on a slope of the railway embankment near the station. The French had made a rapid advance to the river bank, driving the 25ers and 71ers back up the hill. The civilian population had had no time to evacuate in an orderly manner, everything was left intact, the same went for the controllers of the Etappe magazine of Inf.Div.121, who had abandoned the well-stocked dump at the station, and the rolling stock in the goods yard which could not be hauled out because the bridges had been blown. The tracks had been wrecked by numerous shell craters. In the magazine halls, which were under constant bombardment, we found enormous supplies of preserves: peas, beans, whole barrels of cauliflower, great stocks of bedding, and tents, lamps, stoves, sugar, tobacco, etc. Coffee stood ankle-high on the floor, we waded through it. Many drums of paraffin stood around. In one room there were lots of firemen’s brass helmets saved from a museum collection. We set up some tarpaulins to shelter from the rain and cooked a good meal behind and below the goods waggons while the halls were being shelled, which cost us two dead and some wounded. One of the dead had been on leave with me.

In the afternoon the shooting hotted up, and it was really unpleasant in our rabbit holes. There was a terrible noise when a shell exploded in the halls. Despite the ban, several men went into the magazine repeatedly, especially when it became known that there was beer stored there. The following evening, to our great joy some beer was served officially. Towards 2000 the firing abated, and at 2145 we went off to the trenches. There were some aircraft overhead which we took for German because they wore a cross on the wings; they bombed us. We went through the village in groups under fire on the road to Biaches, which we crossed. More heavy fire forced us into a trench where we spent a half hour, we received fire there and a shell landed close by me. They were also firing gas shells. My NCO did not want to get down at first because somebody was out in the open. Finally he had no choice, and the Company Commander helped. Later we went to the reserve trenches where we dug until 0300. Ahead the sky was lit brightly by burning houses.

15 July 1916

Then we went back to Chapelette. After fifteen minutes there we were put on notice to leave for Péronne. We were to cross the river using a narrow improvised bridge balanced on barrels and under constant fire from a heavy battery. We were to run for it between salvoes which came at set intervals. A salvo of three arrived, two of which were duds, and we scampered to the river, arriving without loss. On the other side we entered the abandoned town through a fortress gate and soon found our cellar. Meanwhile it was day and we had to get under cover quickly because the town was in the enemy’s sight and range. I gave a laggard a slap across the head to get him down the cellar, he did not take this the wrong way because he knew it was for his own good. The town had been evacuated suddenly by the population, and the houses had been left as though the owners would return shortly.

In the cellar in which the inhabitants had taken refuge when the shelling began, the food – with mould – was on the table, hats were hung on pegs etc. I had my breakfast drink out of a fine old decorated cup. We reviewed the house from roof to cellar. I moved into a bedroom with Imperial bed and quilt etc. which smelt wonderful. In an alcove were various perfumes etc. I washed using a large bottle of eau-de-cologne and then sprayed myself with perfume. In my filthy uniform and boots I then lay on the young maiden’s bed and slept to 1130. Then I went on a search of neighbouring houses where the other groups were billeted.

In the conservatory I saw from the floor impeccably set tables, each with two plates, serviettes and wine glasses etc. Assuming this was for Staff I was about to withdraw when I discovered a comrade in the kitchen. In response to my enquiry he advised me that ‘Gruppe Hussmann’ dined here. He had all kinds of provisions, mainly preserves and tinned, but also rabbit and smoked meats. There were some well-stocked shops which had ladies’ and children’s shoes. At midday a wine and champagne store was found.

We had preserved meat, potatoes and peas. From 1500 our artillery was to calibrate and was expected to be put out of action by the French guns before nightfall, after which we were to attack. In the afternoon therefore we had to stay in the cellars. When our artillery fire began, the French response was much heavier, and our stay in the town now looked short. The town hall was burning and Lt Hofsummer salvaged the collection of Roman gold coins in a sandbag which he handed over to division. Wehrmann-König and Vohn caused great hilarity dressing up as a bridal pair, he in morning coat and top hat, the bride in white dress with veil, and insisted on making house calls, even on the officers and despite the shelling. Under the influence of the discovered alcohol stocks, the mood became even more high-spirited during the afternoon. A couple of individuals were well over the limit. When we marched out at 1830 we found a rifleman reported AWOL sleeping in the entrance to a cellar and cuddling a large doll. We then quick-marched across the market place towards the Flamicourt district.

At 0200 we advanced. Our Company Commander Lt Mersmann requested Vizefeldwebel Trieschmann to remain with him in the difficult situation. We hastened through the communications trench, stumbling forward over dead and wounded. I still recall treading on something soft which whimpered and I saw that I was standing on the face of a wounded man. After a lot of manoeuvring hither and thither we found ourselves in a dreadful corner, men squashed against men in a two-metre deep trench unable to rest. Shells were flying overhead, the trench had no step-up for riflemen.

We lay here the whole day without food or water until late evening. There was no wire entanglement outside and the trench had no dug-outs. If an orderly officer wanted to pass through, two men had to lie down on their stomachs on top of one another so that passage was possible. Gradually we made scrape-holes in which we could at least shelter head and upper torso. The four men of my group to my left were wounded one after the other and disappeared. I sat in my little hole, abandoned to my fate, waiting for my turn to be wounded, but it never happened. Our Company Commander was mortally wounded by a shell splinter in the upper thigh. Reservist Kirchner and another wounded man making their way to the rear, carried the wounded Company Commander along in a tarpaulin. He was calling for his wife and children. A short while later all three took a direct hit. Mersmann had frequently had Kirchner on report for minor misdemeanours, but this did not prevent Kirchner from helping his officer as a comrade.

Towards 1800 the French started an attack which then faltered. I fired three rounds. At 2100 we were to storm the small wood opposite. The order was passed from hand to hand, the docket was signed, ‘Ordered by God, Siebe.’ When we were ready to go, the assault was called off. No.2 Company Commander Weller was informed by a reconnaissance patrol that our No.1 and No.4 Companies had retaken the wood from the French. So we were in luck. I had three rifles that day, two were damaged beyond repair, I narrowly escaped from being buried alive three times when the trench walls collapsed. When the Company count was made, of the 230 men who had come to the trench only 110 remained. During the night there was a downpour, I looked like a hippopotamus, yellow with mud, in the night we were relieved and returned as reserve to Chapelette where we were billeted in the cellars. When the kitchens arrived, our cook told me he had thought I would not survive out there.

17 July 1916

Our losses so far are nine dead and one hundred wounded. There are many black French troops lying around dead in the countryside. When we were fetching provisions towards 2300, we were put on alert and went forward. I had taken over 1.Platoon, 3.Platoon had three seriously wounded when moving up. We came to the left flank of the position directly facing the small wood at La Maisonette where the 21ers had fired too short. There were still some 10.Company dead lying around dreadfully mutilated, besides that flame-throwers and many armaments rooms.

18 July 1916

On the left flank was a trench with viewing slit. Through this slit one could see the French a few metres away through the viewing slit in their own trench. We had to keep awfully alert because they could almost jump across. During the day it was quieter and the artillery fire tolerable. Our twenty-one-cm shells roared into the French-held wood regularly. At dusk we gathered up the litter and found two cans of meat. We buried three corpses. Our people had just gone off to fetch the coffee and rations when their infantry began an intense fire, then the artillery joined in so that we had the same old story again. It lasted ninety minutes before dying down.

During the day there were numerous aircraft in the air and aerial fights in which three French machines were shot down. One of them hurtled to its fate nearby. Both wings had been shot off, and these twisted and turned in the air as the fuselage fell. The two occupants jumped out and thudded into the soft farmland not far from us. I will never forget the sound when they hit. It was as if somebody had tossed down two potato sacks.

19 July 1916

We had six men wounded. The little wood was peppered with twenty-one-cm shells. This evening we were supposed to be relieved. We were depressed when they failed to arrive, and that evening there was another long barrage which caused us more losses.

20 July 1916