The Westward Travels of the Changes

CHAPTER 5

In several respects the transmission of the Changes to the West parallels the process by which Buddhism and Daoism traveled to Europe and the Americas. In each case Western “missionaries” played a part in the process, and in each case there were varied responses over time, ranging from blind indifference to rational knowledge, romantic fantasy, and existential engagement.1 But in nearly every instance, as in East Asia, there was an effort, often quite self-conscious, to assimilate and domesticate the classic. As with the Koreans, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Tibetans, Westerners sent missions to China, and they brought back all kinds of useful information. But compared to their East Asian counterparts, these Western missions proceeded from very different motives and had a very different focus. Moreover, in contrast to the premodern spread of the Yijing and other texts to Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, where elites were completely comfortable with the classical Chinese script, in the West the Changes required translation, raising issues of commensurability and incommensurability that are still hotly debated today.2

The Jesuits and the Changes

Ironically the westward movement of the Yijing began with the eastward movement of the West. Beginning in the late sixteenth century, in a pattern replicated in many other parts of the world, Jesuit missionaries traveled to China, attempting to assimilate themselves as much as possible to the host country. They studied the Chinese language, learned Chinese customs, and sought to understand China’s philosophical and religious traditions—all with the goal of winning converts by underscoring affinities between the Bible and the Confucian classics. Naturally the Changes served as a major focus for their proselytizing scholarship.3

The Jesuit missionaries labored under a double burden. Their primary duty was to bring Christianity to China (and to other parts of the world), but they also had to justify their evangelical methods to their colleagues and superiors in Europe. A kind of “double domestication” thus took place. In China the Jesuits had to make the Bible appear familiar to the Chinese, while in Europe they had to make Chinese works such as the Yijing appear familiar (or at least reasonable) to Europeans.

One of the primary agents involved in this process was the French Jesuit Joachim Bouvet (1656–1730), who tutored the great Kangxi emperor for up to two hours a day in algebra and geometry. In addition the two men regularly discussed the Yijing, which fascinated both of them. The emperor, who considered Bouvet perhaps the only Westerner who was “really conversant with Chinese literature,” showed a particular interest in the Jesuit priest’s claim to be able to predict the future, including the duration of the world, with numerological charts based on the Changes.4

Bouvet and his colleague Jean-François Fouquet (1665–1741) represented a development in Western Christianity known as the Figurist movement. In brief, the Figurists tried to find in the Old Testament evidence of the coming and significance of Christ through an analysis of “letters, words, persons, and events.” Apart from the literal meaning of the “outer” text, in other words, there existed a hidden “inner” meaning to be discovered. In China this gave rise to a concerted effort to find reflections (that is, “figures”) of the biblical patriarchs and examples of biblical revelation in the Chinese classics themselves.

Bouvet and Fouquet were masters of the Figurist art form. Using a rather strained etymological approach to various written texts, as well as an evaluation of the trigrams and hexagrams of the Yijing, they found all kinds of hidden messages. Dissection of the Chinese character for Heaven ( ) into the number two (

) into the number two ( ) and the word for Man (

) and the word for Man ( ) indicated a prophecy of the second Adam, Jesus Christ. The character for boat (

) indicated a prophecy of the second Adam, Jesus Christ. The character for boat ( ) could be broken down conveniently into the semantic indicator for a “vessel that travels on water” (

) could be broken down conveniently into the semantic indicator for a “vessel that travels on water” ( ) and the characters for “eight” (

) and the characters for “eight” ( ) and “mouth(s)” (

) and “mouth(s)” ( )—signifying China’s early awareness of Noah’s Ark, which contained, of course, the eight members of Noah’s family.

)—signifying China’s early awareness of Noah’s Ark, which contained, of course, the eight members of Noah’s family.

In Figurist discourse a wide variety of Chinese philosophical terms closely associated with the Changes came to be equated with the Christian conception of God, including not only Heaven and the Lord on High, but also the Supreme Ultimate, the Supreme One, the Way, Principle, and even yin and yang. In the Figurist view the three solid lines of the Qian trigram (“Heaven,” number 1) represented an early awareness of the Trinity; the hexagram Xu (“Waiting,” number 5), with its stark reference to “clouds rising up to Heaven” (in the Commentary on the Images), indicated “the glorious ascent of the Savior”; and, of course, the Qian hexagram (number 1) referred to Creation itself. The hexagrams Pi (“Obstruction,” number 12) and Tai (“Peace,” number 11) referred, respectively, to “the world corrupted by sin” and “the world restored by the Incarnation,” and so forth.

In focusing his attention primarily on the imagery, allusions, and numerology of the Yijing, Bouvet was following a path blazed by Chinese Christian writers such as the late Ming convert Shao Fuzhong (fl. 1596), whose book, On the Heavenly Learning, draws on the Great Commentary, hexagram analysis, and the writings of Shao Yong and others in comparing concepts and images in the Yijing with various Catholic doctrines such as the Trinity and the Immaculate Conception. Other Chinese converts wrote similar tracts identifying affinities between Catholic theology and the Changes.

One of Bouvet’s greatest and most persistent desires was to demonstrate a relationship between the numbers and diagrams of the Yijing (especially as expressed in the Yellow River Chart and the Luo River Writing) and the systems of Pythagoras, the neo-Platonists, and the kabbala. This is evident not only in his Chinese-language writings, but also in his broad-ranging manuscripts in Latin. In one such manuscript, for example, he equates the Ain Soph (sometimes translated as “Limitless Divine Creator”) symbol at the top of the Ten Sephiroth (the so-called Tree of Life) with the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate, remarking that the ancient Chinese sages understood the doctrine of “the one and triune God, founder of all things, … [as well as] the incarnation of the Son of God and the reformation of the world through him.” This understanding, Bouvet asserts, was “clearly similar to the ancient kab-bala of the Hebrews,” whether expressed by the “ten elementary numbers and the twenty-two letters of its mystic alphabet,” or by the twenty-two Chinese characters representing the ten heavenly stems and twelve earthly branches as well as the “ten elementary numbers of the mystic figure Ho tu [Yellow River Chart].”5

Bouvet goes on to argue in this tract that the first two hexagrams of the Yijing, Qian and Kun, are the “principal characters of God [as] creator and redeemer.” Qian, “with the numerical power 216, the triple of the tetragram number 72, is the symbol of justice,” and Kun, “with the numerical power 144, double the number 72, is the symbol of mercy.” Together, “taken up with the power of the same tetragram number 72 quintupled, [these numbers] are the symbolic mark of the two principal virtues of the divine Redeemer, outlined in the hieroglyphics of the Chinese just as in the sephirotic system of the Hebrews.” In short, Bouvet concludes, because God “made everything in number, weight, and measure (Sap. XI, 21), … perfecting these in wisdom,” it follows, “by necessity, that the numbers are, so to speak, the fundamental base of all true philosophy, … the sacred wisdom of the old patriarchs … infused in the very first-formed parent of human beings.”6

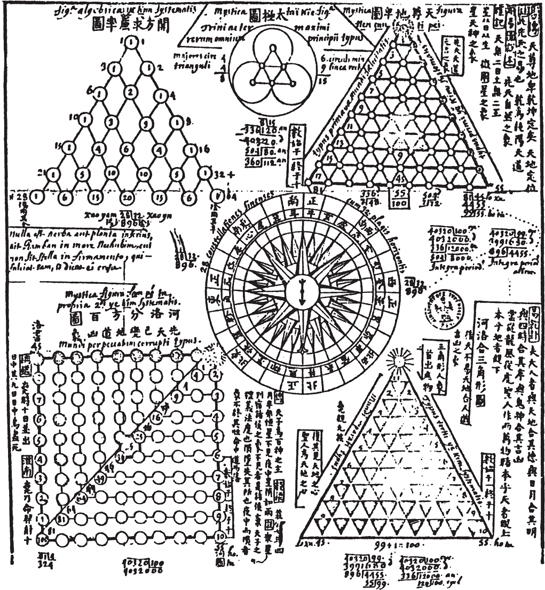

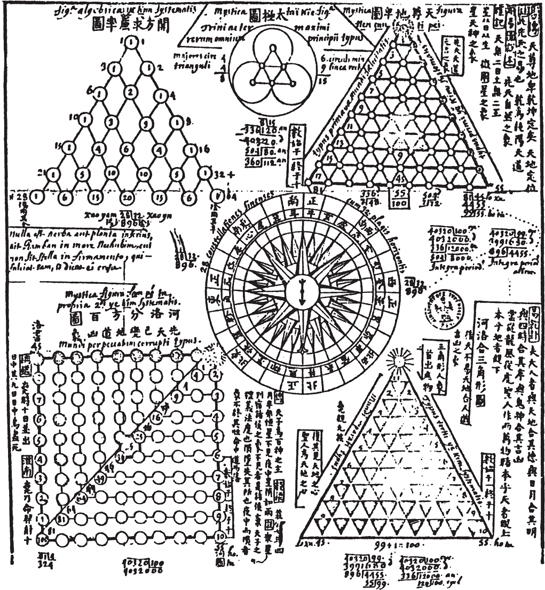

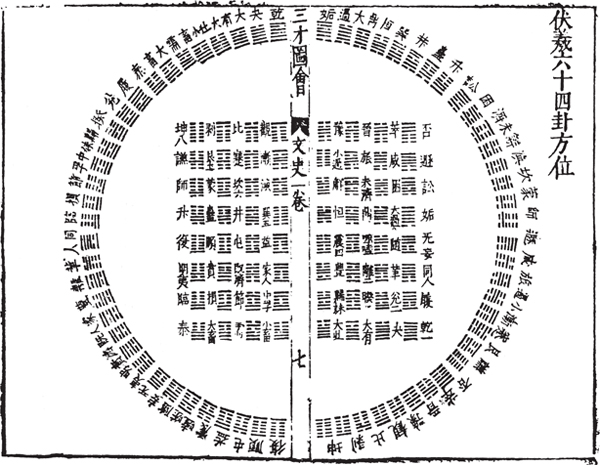

Bouvet’s “Chart of Heavenly Superiority and Earthly Subordination” represents his effort to integrate the numerology of the Yellow River Chart and the Luo River Writing into a single mathematical “grand synthesis,” similar in certain respects to Shao Yong’s Former Heaven Chart. Like Shao’s diagram, but with less schematic economy, the Chart of Heavenly Superiority and Earthly Subordination attempts to convey “the quintessence of heavenly patterns and earthly configurations,” illustrating not only the evolution of but also the mutual interaction between the hexagrams and their constituent trigrams and lines. And like Shao Yong’s numerical calculations, Bouvet’s diagrams were designed to yield an understanding of good and bad fortune as well as an appreciation of the larger patterns of cosmic regularity and cosmic change (see figure 5.1).7

FIGURE 5.1

One Version of Bouvet’s Chart of Heavenly Superiority and Earthly Subordination

This diagram, one of many such illustrations produced by Bouvet and contained in the Vatican Archives as well as in other libraries (the chart depicted here is from the Bibliothèque nationale in France), is based on geometric figures of the sort displayed in figure 3.6. The chart seeks to show the patterns of cosmic change that will lead ultimately to the “Second Coming of Christ.” Originally published in Claudia von Collani’s Joachim Bouvet S.J.: Sein Leben und Sein Werk, Monumenta Serica, Monograph Series 17 (Steyler Verlag, 1985), 169. Reproduced with permission from Monumenta Serica.

Initially the Kangxi emperor’s interest in Bouvet’s ideas was so great that he encouraged the French Jesuit to play an active role in the compilation of the huge annotated edition of the Yijing that was published in 1715 as the Balanced Compendium on the Zhou Changes—which Bouvet indeed did. But eventually the Figurist enterprise, like the broader Jesuit evangelical movement, fell victim to harsh criticisms from Chinese scholars as well as to vigorous attacks by other members of the Christian community in China and abroad. In the end Rome proscribed all Bouvet’s Figurist writings and forbade him to promulgate his Figurist ideas among the Chinese.8

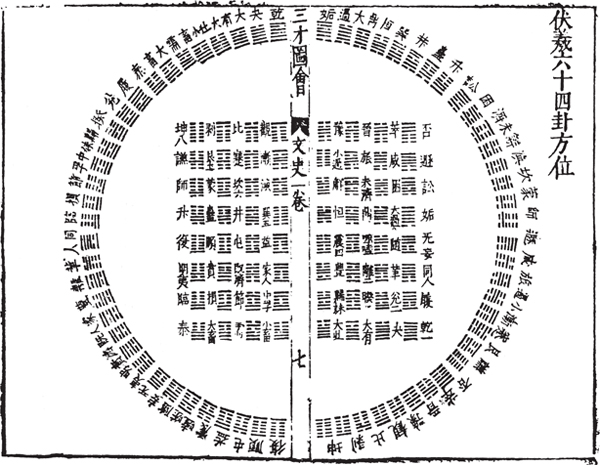

Yet despite the unhappy fate of the Figurists in China, their writings captured the attention of several prominent European intellectuals in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries—most notably the great German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716).9 Leibniz’s interest in China had been provoked by, among other things, his search for a “Primitive Language”—one that existed before the Flood. Both Bouvet and Leibniz believed that the study of the Changes could assist in this quest, and in the creation of a comprehensive scientific/mathematical language that Leibniz referred to as the “Universal Characteristic.” Such a language would make the act of thinking—like the act of calculation—a reflection of the binary structure of nature itself. In their view Shao Yong’s Former Heaven Chart (figure 5.2) offered a mathematical point of entry: a hexagram structure of line changes that expressed exactly the same formal features as the binary system invented by Leibniz himself.

FIGURE 5.2

Shao Yong’s Former Heaven Chart

These circular and square configurations of the sixty-four hexagrams show a progression of line changes that suggested an obvious binary mathematical structure to Bouvet and Leibniz.

When Bouvet sent a copy of Shao Yong’s diagram to Leibniz, the latter was ecstatic to see cross-cultural confirmation of his binary system—a system that had a religious and mystical significance to both of them, denoting the idea that God (represented by the number one) had created everything out of nothing (0).10 But while there are indeed certain similarities between the ideas and approaches of Leibniz and Shao Yong, there are also significant differences. First, the numbers Shao Yong employed in all his calculations were based on the decimal system, as were those of every other commentator on the Changes up to the time of Bouvet. Second, Shao was clearly more interested in correlative metaphysical explanations and analogies between natural bodies and processes than in the binary structure of the Former Heaven Chart per se. On the whole Shao had little interest in quantitative and empirical methods, and he did not share Leibniz’s optimistic belief in linear progress. To Shao all experience was cyclical, and empirical study was merely a technical exercise, like the practice of astronomy or divination.11

Thus, in a sense, the Bouvet-Leibniz exchange serves as a metaphor for the problems facing exponents of a Chinese-Christian synthesis in both China and Europe. Provocative similarities could be identified but not fully exploited, not least because people like Bouvet faced such formidable opposition within the Catholic Church, both from other orders (Franciscans and Dominicans) and from within the Jesuit community itself. Meanwhile, in European secular society, individuals such as Voltaire, who idealized Chinese culture for his own ideological purposes, criticized Leibniz unmercifully for his Panglossian optimism. Thus knowledge continued to be acquired about China, but in a piecemeal fashion, and by the early nineteenth century it came with an increasingly negative spin.

Translating the Changes

The first book in a European language to give substantial attention to the Changes was a Jesuit compilation known as Confucius Sinarum Philosophus (Confucius, Philosopher of the Chinese; 1687). Although acknowledging that the Yijing had been “misused” by Daoist fortune-tellers and “atheists” (i.e., Neo-Confucians), it chronicled the generally accepted history of the document, emphasizing the moral content of the work. Like many Chinese Christians who sought to use the symbols of the Changes to illustrate biblical virtues, the editors of Confucius Sinarum Philosophus focused on the Qian hexagram (“Modesty,” number 15). Following the gloss of a famous Ming dynasty scholar, they pointed out that the lower Gen trigram signifies a mountain rising from the depths of the earth up to the clouds and the stars—a symbol of sublimity and great virtue. The foundations of the mountain lie in the upper trigram, Kun, which signifies Earth—the symbol of modesty with its hidden treasures, bearing fruit for all humankind.12

Significantly the first complete translation of the Changes in a Western language (Latin) was undertaken by three Jesuit scholars who were extremely critical of the allegorical approach adopted by Bouvet and his followers. This anti-Figurist group consisted of Jean-Baptiste Regis (1663–1738), Pierre-Vincent de Tartre (1669–1724), and Joseph Marie Anne de Moyriac de Mailla (1669–1748). All three men denied that the Chinese classics contained any truths of the Christian faith, and they all denounced the Figurists for producing what de Tartre disparagingly called the “Cabala [Kabbala] of the Enochists.”13

Work began on the translation in 1707, but the preliminary draft was not completed until 1723.14 This final version was based on the imperially commissioned Balanced Compendium on the Zhou Changes and its official Manchu rendering. But the Regis manuscript then languished for more than a decade in Paris, until a young sinologist named Julius Mohl (1800–1876) produced a two-volume printed version of several hundred pages in the 1830s titled Y-King antiquissimus Sinarum liber quem ex latina interpretatione P. Regis aliorumque ex Soc Jesu P.P. edidit Julius Mohl (Yijing, the Most Ancient Book of the Chinese, Edited by Julius Mohl Based on the Latin translation of Father Regis and Other Fathers of the Society of Jesus). This version, which drew on other materials in addition to the Regis manuscript, attacked the Figurists as well as the theories of Shao Yong. At the same time, however, in a series of introductory essays, dissertations, and appendices, it addressed most of the major issues of traditional Chinese Yijing scholarship in a systematic way, quoting from orthodox Neo-Confucian sources and citing the authority of the Church fathers and Western philosophers for comparative purposes.15

During the latter part of the nineteenth century, after a long hiatus, a flurry of translations of the Changes appeared in Europe, including Canon Thomas Mc-Clatchie’s A Translation of the Confucian Yi-king (1876); Angelo Zottoli’s 1880 rendering in volume 3 of his Cursus Litteraturae Sinicae neo-missionariis accomodatus (Course of Chinese Literature Appropriate for New Missionaries; 1879–82); James Legge’s The Yi King (1882); Paul-Louis-Felix Philastre’s Tscheou Yi (1885–93); and Charles de Harlez’s Le Yih-king: Texte primitif, retabli, traduit et commente (1889).16 These works reflect a “scholarly vogue in European culture at this time concerned with the uncovering, and the rational and historical explanation, of all manner of apparent Oriental mysteries,” including not only Buddhism and Daoism, but also various forms of spiritualism—notably Theosophy, an eclectic, Asian-oriented belief system focused on self-realization and “oneness with the Divine,” which some have seen as a precursor to the so-called New Age Movement of the 1980s in Europe and the United States.17

Zottoli’s incomplete and undistinguished translation appears to have had a rather limited circulation in Europe, but the renderings by Philastre, a naval officer, diplomat, and teacher, and de Harlez, a Belgian priest and professor, were somewhat more popular, at least in France.18 Both publications have serious limitations as scholarly works, but each is at least comparatively lively and easy to read. Philastre’s problem as a translator is that his renderings are rather loose; the difficulty with de Harlez is that his approach to the Changes is highly idiosyncratic, predicated on the idea that the classic began as a reference book for some unnamed ancient Chinese political figure.19

McClatchie, like Father Joachim Bouvet before him, maintained that the Yijing had been carried to China by one of the sons of Noah after the Deluge. But whereas Bouvet had tried to use the Changes to prove that the ancient Chinese had knowledge of the “one true God,” McClatchie believed that the work reflected a form of pagan materialism, “perfected by Nimrod and his Cushites before the dispersion from Babel.” He identified Shangdi (the ancient Shang dynasty deity) as the Baal of the Chaldeans and pointed to a number of cross-cultural correlations involving the number eight, including the total number of No-ah’s family, the principal gods of the Egyptians, and the major manifestations of the Hindu deity Shiva.20

In addition to offering a relatively straightforward, but not very illuminating, translation of the Changes, McClatchie published two articles in the China Review at about the same time—one titled “The Symbols of the Yih-King” and the other, “Phallic Worship.” In these two works, particularly the latter, he identified the first two hexagrams of the Yijing with the male and female sexual organs, respectively. In McClatchie’s view Qian and Kun represented the “phallic God of Heathendom.” Qian “or his Male portion is the membrum virile,” and Kun “or his Female portion is the pudendum muliebre.” These two, he goes on to say, “are enclosed in the circle or ring, or phallus,” known as the Supreme Ultimate or Great One, from which “all things are generated.”21 Scholars like Legge and, later, the eminent Russian Sinologist Iulian Shchutskii ridiculed this decidedly sexual view (Shchutskii described it as the product of “pseudoscientific delirium”), but recent work by other scholars suggests its essential validity.22

James Legge began his translation of the Changes in 1854, with the later assistance of a Chinese scholar, Wang Tao (1828–97). But for various reasons it was not completed for another twenty years or so.23 Like the Jesuits Legge believed that the Confucian classics were compatible with Christian beliefs, but he was not a Figurist.24 In addition to denouncing McClatchie for focusing on the Yijing’s sexual imagery, Legge assailed him for resorting to the methods of “Comparative Mythology.” In Legge’s dismissive words, “I have followed Canon McClatchie’s translation from paragraph to paragraph and from sentence to sentence, but found nothing which I could employ with advantage in my own.”25

Legge had no love of China and no respect for the Yijing. Indeed, he described it as “a farrago of emblematic representations.” Although admitting that the Changes was “an important monument of architecture,” he characterized it as “very bizarre in its conception and execution.”26 Legge’s highly literal translation followed the prevailing Neo-Confucian orthodoxy of the Qing dynasty as reflected in the Balanced Compendium on the Zhou Changes. His goal was to produce a translation that made it possible for him to downplay aspects of the Yijing he deemed unimportant, such as its imagery and numerology, and to underscore themes he considered essential—not least the obviously mistaken idea that passages in the Explaining the Trigrams commentary refer to the Judeo-Christian God.27

Although Legge’s translation remained the standard English-language version of the Changes until the mid-twentieth century, it provoked a barrage of criticism, beginning with Thomas Kingsmill in 1882. Writing in the China Review, Kingsmill acknowledged that Legge’s rendering was somewhat better than the flawed translations of Regis, Zottoli, and McClatchie, but he faulted the Scottish Sinologue for introducing yet another system of “transcribing Chinese,” and for using too many interpolated words. Kingsmill wrote: “If the translator be at liberty to introduce, even within brackets, matters altogether outside the text, there is no possibility of predicting the result, and, as in this case, an author’s plain words may be made to bear any meaning at the fancy of the manipulator.”28

Soon thereafter Joseph Edkins, a British Protestant missionary who had already spent more than twenty of his fifty-seven years in China, wrote a pair of articles on the Yijing that displayed a striking sensitivity to Chinese scholarship and a remarkable lack of ethno-centric prejudice. Of particular note was his emphasis on the commentaries of the Qing scholar Mao Qiling, and especially Mao’s critique of Song dynasty scholars such as Chen Tuan and Shao Yong. Edkins appreciated the contributions of certain Western scholars, including Legge, but he had none of the latter’s cultural prejudices. Instead he took the Changes on its own terms, as a reflection of the time in which it was created. It is worthwhile, he wisely concluded, “to study the opinions of the wise in all ages.”29

At about the same time (1882–83), but with a far different intellectual orientation from that of Edkins, Albert Étienne Terrien de LaCouperie, a French scholar, wrote a long article that in 1892 became a short volume, The Oldest Book of the Chinese: The Yh-King and Its Authors. Terrien’s study begins with a general discussion of the origin and evolution of the Changes, based primarily on traditional Chinese scholarship. It then evaluates “Native Interpretations” and “European Interpretations” of the Yijing. Although Terrien’s list of Chinese commentators is relatively comprehensive, his opinion of their work is low (the product of what he derisively describes as “tortured minds” and “maddened brains”). Their approach to analyzing the text is, he claims, “undeserving the attention of a man of common sense; it is a compilation of guesses and suggestions, a monument of nonsense.” He states scornfully that there are many educated Chinese who believe that “electricity, steam-power, astronomical laws, [the] sphericity of the earth, etc., are all … to be found in the Yh-King.”30 This belief, as we have seen and shall see again, was commonly held but fundamentally ill-founded.

Terrien had a low opinion of most French, German, Italian, and British scholarship on the Changes. He does praise Zottoli for not translating the text “according to the farcical treatment of many Chinese commentators,” and for “refusing to translate what cannot be translated,” but he describes the Regis translation as “unsatisfactory and utterly unintelligible” and dismisses the McClatchie version as simply a reflection of the author’s preconceived notions, translated “accordingly with Chinese commentators.” Of Philastre’s “mystical” rendering, he notes that the “symbolism of astronomy, electricity, chemistry, etc.” of the Changes is “carried to the extreme,” and that the speculations of the translator have “no other ground than the imagination of the writer.”31 As to Legge’s translation of the Yijing, Terrien describes it as an “unintelligible” English paraphrase of the document, based solely on a “guess-at-the-meaning principle,” “the most obnoxious system ever found in philology.”32

Like Bouvet and his supporters, Terrien sought to locate the origins of the Changes in the West (Central Asia, to be more precise), but his intent was not to domesticate the Yijing in the fashion of the Figurists for he held the conventional text in very low regard. According to Terrien, the Changes originated as a primitive reference work—a “handbook of state management … set forth under the sixty-four words [hexagram names]”—in the ancient kingdom of Akkad, which he believed to be Bactria. By his account, following a great flood, the Bak people migrated eastward to China, having previously struggled with the descendants of the Assyrian king Sargon (i.e., Shennong, successor to Fuxi). He goes on to assert that Prince Hu-Nak-kunte (Yu, founder of the Xia dynasty) then led the Bak people to settle in the Yellow River valley around the year 2282 BCE.33

Iulian Shchutskii’s critique of Terrien is as devastating as Terrien’s critique of his predecessors. Shchutskii writes, for example, that Terrien does “savage violence” to the text of the Changes and “completely dismisses the commentary tradition,” quoting only “the most ancient layer” of the basic text and placing it “in the Procrustean bed of his own arbitrariness.”34 Legge’s translation of the Yijing fares a bit better, but, somewhat ironically in the light of the criticisms of Terrien, Shchutskii faults the British missionary for relying too heavily on Chinese commentaries.

None of these early translations of the Yijing enjoyed much popularity in the late nineteenth century. Although the period witnessed a certain vogue for occult writings in Europe, the Changes was simply too obscure to appeal to a broader public readership. During the 1920s, however, the situation began to change dramatically. In 1924 the missionary-scholar Richard Wilhelm (1873–1930) published a German translation of the Changes titled I Ging, Das Buch der Wandlungen, which became a global sensation when it was translated into English by one of Carl Jung’s students, Cary Baynes, and published in 1950 as I Ching, The Book of Changes. That same year Annie Hochberg-van Wallinga translated the German text of Wilhelm’s book into Dutch, and Bruno Veneziani and A. G. Ferrara translated it into Italian. Translations in other European languages followed in fairly rapid succession.35

In certain respects Wilhelm’s translation was like Legge’s. It was heavily annotated, produced with assistance from a Chinese scholar (Lao Naixuan, 1843–1921), and based on the Qing dynasty’s Balanced Compendium on the Zhou Changes, which gave the document a decidedly Neo-Confucian cast. But Wilhelm’s translation was far smoother, and it reflected a much different worldview. The standard comparison of the two works—somewhat of a distortion on both ends—is that Legge’s text indicates what the Yijing says while Wilhelm’s conveys what it means.36 In fact Wilhelm’s rather didactic tone and his elaborate explanations of the features and functions of the Changes are strikingly reminiscent of primers such as the famous Ming dynasty work by Huang Chunyao (1605–45) titled Understanding the Yijing at a Glance.37

Another interesting point about Wilhelm’s translation is that it bespeaks a person who not only was in love with China but also believed that the Yijing had something important to say to all humankind. Like Bouvet he considered the Changes to be a global property and a work of timeless wisdom. Unlike Bouvet, however, he treated it solely as a Chinese document, with no genetic links with either the ancient West or the Near East. This said, it should be noted that Wilhelm—like many scholars before him in both Asia and Europe—tried to domesticate the Yijing in various ways. One was to call on the authority of classical German philosophers and literary figures like Kant and Goethe to illustrate “parallel” ideas expressed in the Changes. Another was to cite the Bible for the same purpose. Yet another was to argue that the Yijing reflected “some common foundations of humankind,” which all cultures were based on, albeit “unconsciously and unrecognizedly.” Wilhelm believed, in other words, that “East and West belong inseparably together and join hands in mutual completion.” The West, he argued, had something to learn from China.38

Wilhelm also tried to “demystify” the Changes by providing elaborate commentaries that paraphrased and explained away the “spiritual” material that he felt might “confuse the European reader too much with the unusual.” This strategy of “rationalization” was somewhat similar to that of the Jesuit Figurists, “who frequently prepared second translations of certain texts because they claimed to know the intrinsic meaning of these texts: the prefiguration of Christian revelation.”39 In the case of the Figurists, this process often involved the willful misrepresentation (or at least the ignoring) of traditional commentaries in order to “dehistoricize” the “original” text. But in Wilhelm’s case, most of his interpretations reflected the basic thrust of Cheng-Zhu orthodoxy as reflected in the Balanced Compendium on the Zhou Changes. Moreover they fit the general climate of rational academic discourse in early-twentieth-century Europe. Wilhelm remained a missionary, so to speak, but a secular one whose rendering of the Changes seemed to confirm Carl Jung’s theories about archetypes and “synchronicity”—just as Bouvet’s representations of the work had confirmed Leibniz’s binary system and fed his speculations about a “Universal Characteristic.”

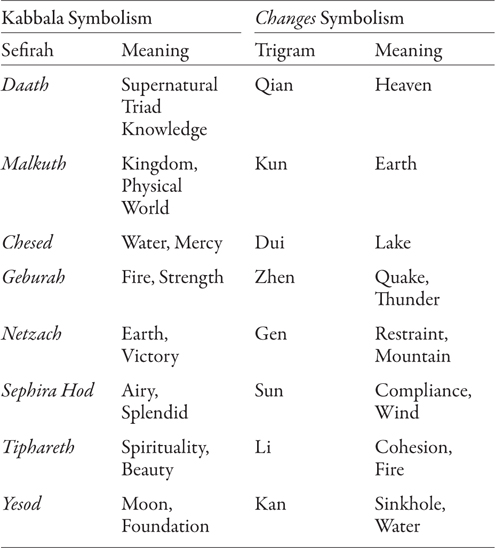

By contrast, Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), an enthusiastic British exponent of Theosophy who traveled to China during the first decade of the twentieth century, adopted a self-consciously mystical approach to the Changes—a harbinger of countercultural enthusiasm for the document that would peak worldwide in the 1960s and 1970s. Upon his return from China, Crowley undertook the study of various Chinese texts, including the Yijing. He relied heavily at first on Legge’s translation but found it wanting—not least because of the Scottish missionary-translator’s hostility to the document (“what pitiable pedantic imbecility,” Crowley once wrote of Legge’s attitude). Eventually he developed an approach to the classic that dispensed with the conventional attributes of some of the trigrams and tried to assimilate them, in the fashion of Bouvet, into the kabbalistic “Tree of Life.”

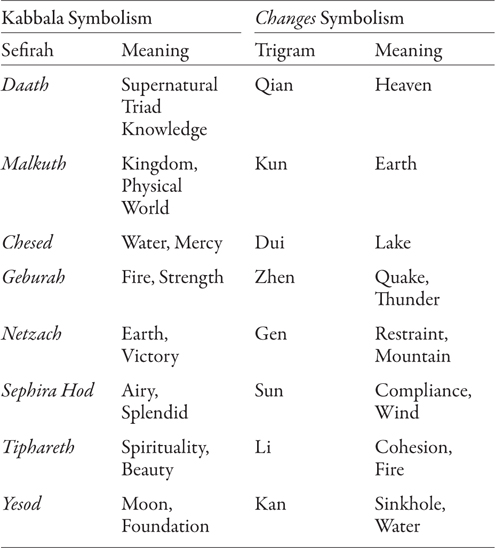

According to Crowley the Yijing “is mathematical and philosophical in form,” and its structure “is cognate with that of the Qabalah [Kabbala].” The identity is so intimate, he claims, that “the existence of two such superficially different systems is transcendent testimony to the truth of both.” In Crowley’s view the Dao as expressed in the Yijing was “exactly equivalent to the Ain or Nothingness of our Qabalah,” and the notions of yang and yin “correspond exactly with Lingam and Yoni.” Furthermore he equated the Chinese idea of “essence” with Nephesh (“anima soul”), “qi” with Ruach (“intellect”), and “soul” with Neschamah (the “intuitive mind”). For Crowley the Confucian virtues of benevolence, moral duty, ritual propriety, and humane wisdom suggested the kabbalistic principles of “Geburah, Chesed, Tiphareth, and Daath.”40

In Crowley’s decidedly sexual interpretation of the Changes, reminiscent of McClatchie’s, the eight trigrams represent (1) the male and female reproductive organs, (2) the sun and the moon, and (3) the four Greek elements—earth, air, fire, and water. The table on page 193 gives the highly imaginative Kabbalistic correlations identified by Crowley.

With similar abandon Crowley equates the four attributes of the judgment for the first hexagram, Qian—yuan, heng, li, and zhen—with the four spheres of the Tree of Life and the four parts of the human soul, representing wisdom, intuition, reason, and the animal soul.41

In more recent times a great many books and articles have attempted to relate the Yijing to the values of Christianity and/or Judaism and to employ Figurist techniques and logic. Representative works include Joe E. McCaffree’s massive Bible and I Ching Relationships (1982; first published in 1967); C. H. Kang and Ethel R. Nelson’s The Discovery of Genesis (1979); Hean-Tatt Ong’s The Chinese Pakua (1991); and Jung Young Lee’s Embracing Change: Postmodern Interpretations of the I Ching from a Christian Perspective (1994). In addition to religiously oriented texts of this sort, many New Age or special interest versions of the Changes have appeared during the past few decades, bearing titles such as The I Ching and Transpersonal Psychology, Self-Development with the I Ching, The I Ching Of Goddess, I Ching Divination for Today’s Woman, The I Ching Tarot, Death and the I Ching, The I Ching on Love, Karma and Destiny, The I Ching of Management: An Age-Old Study for New Age Managers, and my personal favorite, The Golf Ching: Golf Guidance and Wisdom from the I Ching. Many of these works are not actually translations, and some of them are quite amusing. Cassandra Eason, author of I Ching Divination for Today’s Woman, for instance, writes: “While our mighty hunters are keeping a weather eye for potential concubines on the 17.22 from Waterloo to Woking, the Woman’s I Ching uses the back door to enlightenment.”42

Dozens of more rigorous translations of the Changes have appeared in print since the 1960s, in a variety of Western languages.43 As with earlier academic renderings of the Yijing, they all have value and they all have limitations—in part because, as Daniel Gardner reminds us, “there simply is no one stable or definitive reading of a canonical text.”44

The Yijing in Modern Western Culture: A Few Case Studies

From the 1960s onward, the influence of the Changes has been substantial and persistent in the West, but less as a cultural phenomenon than as a countercultural one. Putting scholarly interest aside, its appeal can be explained primarily by the challenge the book seems to pose to conventional Western values. Ironically, however, it has been heavily commercialized in recent years, as can be seen from the volume by Edward Hacker, Steve Moore, and Lorraine Patsco titled I Ching: An Annotated Bibliography (2002). This work evaluates more than a thousand Changes-related products designed for English-language speakers alone—mostly books, dissertations, articles, and reviews, but also records, tapes, CDs, videos, computer software, cards, kits, and other devices. The number of these products has increased steadily, and sometimes dramatically, in recent years, and they have reached virtually all parts of the Western world as well as Asia.45

As a child of the 1960s and 1970s, I still recall vividly the many ways that the Yijing entered the counter-culture of the United States. One of them was through an enormously influential book by Fritjof Capra titled The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism (1975). As the subtitle suggests, Capra’s basic idea was that an affinity exists between the ideas of quantum mechanics and various Eastern philosophies. In his view the Yijing provided an excellent example of quantum field theory—S-matrix theory in particular—and of “the dynamic aspect of all phenomena.”46 By the time The Tao of Physics appeared in print, Asia had begun to figure prominently in the media in the United States (thanks in particular to China’s Cultural Revolution and the Vietnam War), and government support for Asian studies had begun to influence the curriculum of American colleges and universities nationwide.

Capra’s book, which would soon become a best seller, received a highly favorable review in Physics Today (August 1976) from Victor Mansfield, a professor of physics and astronomy at Colgate University, who had himself written various papers and books connecting physics to both Buddhism and Jungian psychology. Other reviewers, however, were far less charitable—especially since the November Revolution of 1974, which marked the discovery of the so-called Psi particle, had fundamentally undermined the version of quantum mechanics that Capra happened to be expounding. But Capra’s critics missed the point in a certain sense: he was not writing physics; he was writing “modern mystical literature.”47 And this literature was powerfully attractive, especially if it had the imprimatur of modern science.

An article that Capra wrote in 2002, titled “Where Have All the Flowers Gone? Reflections on the Spirit and Legacy of the Sixties,” captures some of the attraction, although it fails to mention dramatic curricular changes in postsecondary education and the powerful countercultural forces exerted by the political and social movements of the time, which focused on the Vietnam War, civil rights, women’s liberation, and more general issues of political and personal freedom (including sexual liberation). He writes: “The radical questioning of authority and the expansion of social and transpersonal consciousness [in the 1960s] gave rise to a whole new culture—a ‘counterculture’—that defined itself in opposition to the dominant ‘straight’ culture by embracing a different set of values.” The members of this alternative culture, who were called “hippies” by outsiders, possessed a strong sense of community. Capra notes: “Our subculture was immediately identifiable and tightly bound together. It had its own rituals, music, poetry, and literature; a common fascination with spirituality and the occult; and the shared vision of a peaceful and beautiful society…. In our homes we would frequently burn incense and keep little altars with eclectic collections of statues of Indian gods and goddesses, meditating Buddhas, yarrow stalks or coins for consulting the I Ching, and various personal ‘sacred’ objects.”48

This account rings true as far as it goes. But two things are lost in it: First is the fact that one did not have to be a hippie to explore and experiment; “straights” discovered that they could also join the fun. Second is the fact that youthful exploration and experimentation went on in much of the rest of the world in the 1960s and 1970s, not just in the United States. The major centers of countercultural activity in the Western world were San Francisco, New York, London, Paris, Amsterdam, West Berlin, and Mexico City.

One of the most remarkable efforts to link the Yijing to the drug culture of the 1960s and 1970s was a book by Terence McKenna and Dennis McKenna titled The Invisible Landscape: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching (1975). In it the authors combine investigations into “the molecular basis of Amazonian shamanic trance” with speculations about the divinatory functions, calendrics, alchemy, and mathematics of the Changes. Their particular interest is in the way “different chemical waves” that are “characteristic of life” are reflected in the patterns of trigrams and hexa-grams in the Yijing—Shao Yong’s Later Heaven sequence of the hexagrams in particular.49

Aside from drugs, the most productive path to spiritual liberation in the Western counterculture appeared to be psychological. In 1961, after about a decade on the American scene as a rather cumbersome two-volume set, a handy one-volume edition of Richard Wilhelm’s The I Ching or Book of Changes, with Carl Jung’s original foreword, appeared in print. Jung’s foreword, designed explicitly to illustrate the method of the Changes by means of a detailed divination, emphasized the need for honest reflection and acute self-awareness. “Even to the most biased eye,” Jung states, “it is obvious that this book represents one long admonition to careful scrutiny of one’s own character, attitude, and motives.”50

The notion of creative self-understanding proved to be extremely appealing not only to laypersons but also to clinical practitioners, leading in time to a branch of Jungian psychology that increasingly used the Yijing as a therapeutic device. An early example can be found in Jolande Jacobi’s essay in Jung’s Man and His Symbols (1964), in which Jacobi’s patient, “Henry,” on his therapist’s advice, uses the Changes to interpret a dream. Uncannily (or not), the symbolism of the two primary trigrams of the chosen hexagram, Meng (number 4, “Youthful Folly” in Wilhelm’s rendering), coincided precisely with the symbols that had emerged in Henry’s recent dreams, provoking a breakthrough in his therapy.51

In 1965 the self-styled Buddhist “missionary” John Blofeld published a short, inexpensive, and easy-to-read version of the classic titled I Ching, the Book of Change. This work—expressly designed “for those who wish to live in harmonious accord with nature’s decrees but who naturally find them too inscrutable to be gathered from direct experience”—contributed substantially to public interest in the document.52

Soon references to the Changes began to appear everywhere in Western popular culture. As early as November 27, 1965, Bob Dylan gave an interview published in the Chicago Daily News in which he described the Yijing as “the only thing that is amazingly true, period.” He added: “besides being a great book to believe in, it’s also very fantastic poetry.”53 In 1966 Allen Ginsberg, founding father of the Beat generation of the 1950s and a major countercultural figure of the 1960s, wrote a widely distributed poem titled “Consulting I Ching Smoking Pot Listening to the Fugs Sing Blake.” John Lennon sang of the Changes in “God” (1970), and the New York Sessions version of Dylan’s acclaimed “Idiot Wind,” recorded in the mid-1970s, contains the following line: “I threw the I-Ching yesterday, it said there might be some thunder at the well.”54 (Either Dylan has his trigrams and hexagrams mixed up here or he has produced a very sophisticated reading of the relationship between the Zhen hexagram, number 51, and the Jing hexagram, number 48.)

Perhaps the most famous example of an early Yijing-inspired literary work in the West is Philip K. Dick’s award-winning novel The Man in the High Castle (1962). It tells the story of America in the early sixties, some twenty years after defeat by Nazi Germany and Japan in a titanic war has resulted in joint military occupation of the United States. Slavery is legal, anti-Semitism is rampant, and “the I Ching is as common as the Yellow Pages.” Dick used the Wilhelm version of the Changes on several occasions in devising the plot (which has no denouement because, he later claimed, the Yijing provided no clear guidance), and he also integrated the work directly into the text. Nearly every character in the book consults the hexagrams, which naturally foreshadow the events that will unfold.55 Like the poetry of Ginsberg and the lyrics of Dylan and others, Dick’s novel both reflected the cultural importance of the Changes at the time and contributed substantially to it.

In Europe the influential French novelist and poet Raymond Queneau (1903–76) had a long-standing and intense interest in the Yijing (initially sparked by Philastre’s translation and later reignited by Wilhelm’s).56 From 1960 to the early 1970s, he largely abandoned numerology and occult metaphysics in favor of a more “modern” view of mathematical structures and properties, but he returned to numerology in his last major work, a collection of prose poems titled Morale èlementaire (Elementary Morality; 1975). The theme of these verses is one of constant mutation—in Queneau’s words, the idea that what has changed has “really changed and it will change again.”57

Here is an example of one piece that cleverly inter-mingles yin and yang imagery from the Changes:

Everything started up the moment the sun rose. The mare pulls the cart, the bullock slips on its yoke, the rooster again sings its parting song. On the white leaf there is just one mark while the green one multiplies into myriad images. On hearing all this the rock no longer waits for either the crowd or the chisel. It is the beginning of the recording of all things. The geometer considers the empty ensemble and deduces from it the sequence of whole numbers. Irrationals and transcendants step in to nourish their uncountable thread. The grammarian discovers the passive conjugation. The child—it is a girl—sculpts a fairy from unctuous wax, plastic and polychromatic.58

This short prose poem is based ostensibly on the attributes of the Kun hexagram (number 2, “Receptive” in the Wilhelm translation), which are generally viewed as yin qualities: earth, passivity, femininity, and so forth. The judgment of the hexagram emphasizes the value of perseverance in the mare, and in keeping with the yin theme, we find not only an expressly female horse at the beginning of the work but also an expressly feminine child at the end of it—not to mention an expressly feminine “model/subject.” There is also emptiness and parting. Even the grammatical voice is passive. In Queneau’s synoptic plan of the third section of Morale élémentaire, he refers to “passivity, the birth of all things.”

Yet most of the remaining symbolism in the piece is decidedly yang. The mare, bull, and rooster act assertively; the stone is no longer passive; the child actively fashions something; and there are several beginnings (yang): the start of a day, with sunrise and a cock crowing; multiplicity from oneness; and something from nothing.59 Thus in a single poem Queneau has not only encapsulated a dynamic yet traditional Chinese worldview based on the theme of yin-yang alternation, interaction, and interpenetration, but also a modern Western one, based on the language of numbers.

If we turn our gaze to Latin America, we see further evidence of the global spread of the Changes, exemplified by Jorge Luis Borges’s famous poem “Para una Versión del I King” (For a Version of the Yijing). Jose Luis Ibañez of the Universidad Nacional Autunoma de Mexico tells us: “I learned to consult it [the Yijing] when Octavio Paz taught me in 1958. Back then we could only read Wilhelm’s version in English with that amazing introduction by Carl Jung. A few years later the Beatles, with their attention on the Orient, contributed to the popularization of the document as one that was … [within] the reach of everyone.”60

Of the many Mexican writers influenced by the Changes—including Salvador Elizondo, José Agustín, Jesús Gonzalez Dávila, Juan Tovar, Francisco Cervantes, Sergio Fernández, Daniel Sada, Alberto Blanco, Francisco Serrano, and José López Guido—Octavio Paz, a 1990 Nobel Prize winner in Literature, is perhaps the best known. Long enamored of Asia, he traveled there as early as 1951 and obtained an English-language version of Wilhelm’s translation of the Yijing, which remained among his most beloved books until the day he died in 1998.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Paz, like Queneau, developed an international network of writers, artists, and musicians, many of whom drew upon the Yijing for creative inspiration. Locally, one of the most distinguished of these individuals was José Agustín. Agustín first encountered the Changes in the early sixties and instantly took to the book, fascinated by the notion that an image could be as expressive and powerful as a narrative, and by the idea that the Yijing could be used as a structuring device. His 1968 novel Cerca del Fuego (Near the Fire) is based on sixty-four separate texts, and many of its passages reflect descriptions of the hexagrams. In 1977 Agustín wrote an experimental work titled El Rey se Acerca a Su Templo (The King Approaches His Temple), which combines poetry and prose and also relies heavily on the Yijing. The first section, for instance, features the Lü hexagram (“Treading,” number 10), and each of its six sub-headings reflects its six lines.61

Another of Paz’s close associates in Mexico was his disciple Francisco Serrano, who also experimented with the use of the Changes as a literary device, especially in poetic composition.62 Among the visual artists in their creative circle were painters such as Arnaldo Coen, Arturo Rivera, Augusto Ramírez, and Felipe Erenberg, all of whom found inspiration and guidance in the Yijing. The same was true of the leading musician in the group, the composer Mario Lavista. Dramatists interested in the Changes included Hugo Argüelles, Emilio Carballido, and a younger generation represented by Carlos Olmos and González Dávila.

By virtue of their common interest in the Changes, several of these individuals, including Paz, Serrano, Coen, and Lavista, came to know the American composer John Cage, whose visit to Mexico City in 1976 to celebrate his sixty-fourth birthday provided the occasion for a creative collaboration involving design, music, and poetry titled Mutaciones, Jaula, In/cubaciones (Change, Cage, In/cubations). It may have been on this occasion that Paz used the Yijing to write a poem for Cage, who had become his good friend. After casting three coins and deriving a hexagram, Paz picked up a copy of Cage’s book, Silence, and, guided by the Changes imagery he encountered, chose a few phrases from Cage’s work to which he added some lines of his own.63

Cage deserved all this attention because he was, until his death in 1992, the foremost practitioner of Yijing-related music composition in the United States, with a global reputation and a worldwide network of followers. He first learned about the Yijing in 1936, and in the 1940s he occasionally consulted the Legge translation. But it was not until 1950—the year that Wilhelm’s translation of the Changes first appeared in English—that he began composing with it, a practice he continued until the end of his career.

In 1951 Cage produced Music of Changes, one of his first fully “indeterminate” musical pieces, which identified the Yijing expressly as the source of his inspiration. A decade later, in his groundbreaking book of essays titled Silence (1961), which the critic John Rockwell of the New York Times described as “the most influential conduit of Oriental thought and artistic ideas into the artistic vanguard—not just in music but in dance, art and poetry as well,”64 Cage describes how he created the two-part composition known as Piano 21–56 (1955). Part of the process involved random operations with the Yijing to determine “the number of sounds per page.” After establishing the clefs, bass or treble, with coin tosses, he then divided the sixty-four hexagram possibilities of the Changes into three categories: “normal (played on the keyboard); muted; and plucked (the two latter played on the strings of the piano).” For example, he writes, “a number 1 through 5 will produce a normal; 6 through 43 a muted; [and] 44 through 64 a plucked piano tone.” Cage used a similar technique to determine whether a tone was natural, sharp, or flat, “the procedure being altered, of course, for the two extreme keys where only two possibilities exist.”65

Cage did not use the Yijing simply to generate random numbers; he also cited its wisdom in essays and poetry, “asked it questions” in the course of composing, and relied on it for supplying rhythm and timing in much of his work. In The Marrying Maiden: A Play of Changes (1960), he and playwright Jackson Mac Low used the hexagrams of the Yijing not only to produce the musical score but also to develop character and dialogue.66 In addition Cage employed the Changes in the production of his striking visual art (he produced drawings, watercolors, and etchings, excellent examples of which can be seen in the 116 images in Kathan Brown’s John Cage—Visual Art: To Sober and Quiet the Mind; 2000).

Cage’s approach to the Changes, as he once described it, was to “ask the I Ching a question as though it were a book of wisdom, which it is.” “What do you have to say about this?” he would ask, and then he would “just listen to what it says and see if some bells ring or not.” On another occasion he remarked that he used the Changes “as a discipline, in order to free my work from my memory and my likes and dislikes.” In 1988, toward the end of his life, he wrote: “I use the I Ching whenever I am engaged in an activity which is free of goal-seeking, pleasure giving, or discriminating between good and evil. That is to say, when writing poetry or music, or when making graphic works.” He also used the I Ching as a book of wisdom, but not, he claimed, “as often as formerly.”67

Cage’s experimental music of the 1950s had broad repercussions. It is often credited with launching the Fluxus (“flowing”) international network of artists, composers, and designers who were located in Europe (especially Germany) and Asia (especially Japan) as well as the United States—individuals who sought to blend different visual and musical media in creative ways.

Several composers found inspiration in Cage’s work with the Yijing. One of the first of these was Udo Kasemets, an Estonian-born Canadian composer, conductor, pianist, organist, and writer. Like Cage, Kasemets used the Changes in his compositions and sometimes acknowledged it explicitly in the titles of his compositions—for instance, Portrait: Music of the Twelve Moons of the I Ching: The Sixth Moon (for piano, 1969); I Ching Jitterbug: 50 Hz Octet (8 winds/bowed strings, 1984); and The Eight Houses of the I Ching (for string quartet, 1990). The titles of Kasemets’s compositions often reflect the human sources of his inspiration, which include many of the individuals discussed above: Cage (many times), Duchamp, Paz, and Cunningham (notably, the John Cage/Octavio Paz Conjunction, 1996). In 1984 Kasemets produced 4-D I Ching, offering sixteen tapes with 4,096 combinations (the latter number represents the total possible permutations of the hexagram lines of the Changes: 64 × 64).

James Tenney is yet another famous composer inspired by Cage and the Yijing. Each of his Sixty-Four Studies for Six Harps (1985) is correlated with a hexagram, partly, as he put the matter, “for poetic/philosophical reasons, but also—perhaps more importantly—as a means of ensuring that all possible combinations of parametic states would be included in the work as a whole.”68 In Tenney’s highly sophisticated and heavily mathematical work, each individual “study” is named after one of the sixty-four hexagrams. The correlations are based on configurations of adjacent digrams (two-lined structures; see chapter 3), each of which represents one of four possible states in a parameter: a broken (yin) line over a solid line (yang) is a low state; two broken lines is a medium state; a solid line over a broken line is a high state; and two solid lines is a full state. Thus hexagram 59 (Huan, or “Dispersion” in the Wilhelm translation used by Tenney), associated with Tenney’s fifth study, has a high “pitch state,” a medium “temporal density state,” and a full “dynamic state.” And then things get complicated.69

Among the many famous artists touched by John Cage’s creativity was the dancer and choreographer Mercier (“Merce”) Cunningham, who became Cage’s life partner and frequent collaborator (they first met in the 1930s). One characteristic feature of Cunningham’s performances is that he often used the Yijing to determine the sequence of his dances. Like Cage, Cunningham regularly collaborated with artists of other disciplines, including musicians such as David Tudor; visual artists such as Jasper Johns, Marcel Duchamp, Robert Rauschenberg, and Bruce Nauman; the designer Romeo Gigli; and the architect Benedetta Tagliabue.

Transnational collaboration and cross-fertilization of this sort profoundly influenced the intertwined worlds of avant-garde literature, music, and art in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s—and much more could certainly be said about the process. A great deal more might also be said about the way that organizations such as the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California, and its various European counterparts served as venues for extensive and intensive cross-cultural and inter disciplinary conversations about language, art, literature, philosophy, religion, and science, many of which naturally involved the Yijing. Yet another fertile field of inquiry would be the worldwide explosion of interest in the theories and practices of fengshui and Traditional Chinese Medicine, both of which have long been closely linked to the philosophy and symbolism of the Changes.70

Still another fruitful approach to the spread of the Yijing in the West would be a systematic examination of the many books and articles on the mathematical and scientific applications of the Changes that have appeared over the past few decades. I have perused dozens of such works, with titles such as Bagua Math, I-Ching Philosophy and Physics, and DNA and the Yijing, both in print and in manuscript form. These studies are, to say the least, of remarkably uneven quality, but they are invariably fascinating.

Many such manuscripts have been deposited in the archives of the Needham Institute at Cambridge University, together with correspondence between the authors of these works and various luminaries, including Joseph Needham, Arnold Toynbee, and Francis H. C. Crick (codiscoverer of the double-helix structure of DNA in 1953, which won him the Nobel Prize in 1962). When Professor Needham received a copy of a work that seemed somehow to be beyond his vast competence, he would send it to a colleague, as he did with a 1973 manuscript titled “The I-Ching, The Unraveled Clock: Reconstruction of the Mathematical Science of Prehistoric China,” written by a scholar self-described as a Harvard graduate and a former Ph.D. candidate at the University of Toronto in both anthropology and Chinese. Here is the letter that Professor Crick’s secretary sent to the author of the manuscript on June 1, 1973:

Dear ______ [I have elided the name for obvious reasons],

Dr. Crick has asked me to return to you your manuscript entitled, “The I-Ching, The Unraveled Clock” as it appears to him to be complete nonsense from beginning to end.

Yours sincerely,

(Miss) Sue Barnes

Secretary to

Dr. F.H.C. Crick

Undaunted, this particular person went on to publish in the next two decades at least three books on the relationships among the Yijing, astronomy, mathematics, and chemistry.

) into the number two (

) into the number two ( ) and the word for Man (

) and the word for Man ( ) indicated a prophecy of the second Adam, Jesus Christ. The character for boat (

) indicated a prophecy of the second Adam, Jesus Christ. The character for boat ( ) could be broken down conveniently into the semantic indicator for a “vessel that travels on water” (

) could be broken down conveniently into the semantic indicator for a “vessel that travels on water” ( ) and the characters for “eight” (

) and the characters for “eight” ( ) and “mouth(s)” (

) and “mouth(s)” ( )—signifying China’s early awareness of Noah’s Ark, which contained, of course, the eight members of Noah’s family.

)—signifying China’s early awareness of Noah’s Ark, which contained, of course, the eight members of Noah’s family.