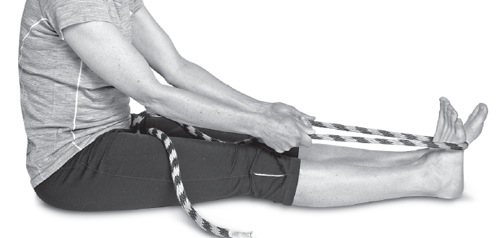

Testing ankle dorsiflexion.

IN MARCH 2012, a woman runner came to sport podiatrist Brian Fullem’s office in Tampa, Florida, with a sore foot. While talking with the woman, Fullem suspected she had a stress fracture. He asked her about her running. She said she had recently started training for a marathon and had switched shoes.

“I asked why she’d switched shoes,” Fullem says, “and she said, ‘I read Born to Run and saw we’re not supposed to be running in regular shoes, and the Kenyans run barefoot, and so I figured I’d start running in minimalist shoes.’” She had discarded her conventional training shoes to do all her running in a barefoot-style model. Fullem knew what to tell this patient because she wasn’t the first such case he’d seen in recent years.

“I told her that you can’t just go from wearing running shoes with a 12-millimeter heel-to-toe drop to a shoe that doesn’t have any cushioning, any support,” he says. “I told her Born to Run isn’t coming from any sort of science perspective, but from the perspective of telling a story about the Tarahumara, who run all day in these handmade sandals. I told her that’s not her, and that there has to be a transition into minimalist shoes.”

Up in Washington, DC, and New York City, physiotherapist Phil Wharton was seeing patients with similar pains—and recent histories. “Because of all the awareness, we’ve seen people jump in too fast or without a proper progression plan,” he says about injured would-be minimalists. “Think about it like this: You get a device like this phone I’m using now. I certainly don’t read the manual or the fine print. I don’t even look at the quick-start guide. I just get it and start using it, and I don’t know what I’m doing.

“And that’s kind of what’s happening with people in minimalism. They remember parts of Born to Run. They don’t remember the part where Christopher McDougall says he had a personal trainer and did strengthening. What they remember is ‘getting into a minimalist shoe changed my life and stopped all these injuries.’ And so they just jump right in.

“The biggest pitfall is that we’re a culture that’s not designed to look at process,” Wharton continues. “When we want to do something, we want to do it 100 percent, starting today.”

In this chapter, we’ll look at a better way of becoming a minimalist than the all-at-once mode that felled Fullem’s and Wharton’s patients and thousands of other overeager runners. We’ll see how to gradually integrate minimalism into your running to minimize your chance of injury and maximize your chance of long-term success.

As we’ve seen in earlier chapters, running in shoes that are lower to the ground, more level, and less cushioned than conventional running shoes places different demands on your body. To quickly recap: Your feet need to be stronger, your plantar fasciae and Achilles tendons need to be longer, your postural muscles need to be functioning well, and so on. Even your neuromuscular system needs to be ready to work differently, as you use more proprioceptive feedback than when running in thickly cushioned shoes that blunt those messages among muscles, nerves, and brain.

So why not just suck it up, start running in minimalist shoes, and allow your body to adapt? Wharton puts it this way: “What I see a lot is people wearing minimalist shoes and running with terrible form. So they go to a form clinic and they fix their form. That’s going to last about 2 weeks before it wears off because they can’t hold their form if their bodies aren’t ready. People have to take a step back and make sure their body is working correctly first.

“We know minimalism is good, but here’s the rider to the contract,” Wharton continues. “The precursor is you gotta make sure your body is working correctly. Otherwise, you’re going to get the injuries we see with minimalism. That’s where the real gung-ho folks are going to come up against a brick wall if they’re not addressing this.”

There’s enormous variability among runners in how prepared their bodies are for minimalism. This is true even among runners of the same age, gender, build, and lifetime mileage, among other factors. There are, however, a few common limiting factors in runners successfully transitioning to minimalism.

Below are five tests. Some were developed by Wharton, some by physical therapist Jay Dicharry, formerly the director of the SPEED Performance Clinic at the University of Virginia. Each targets one of the prime bodily needs for long-term, injury-free minimalism. If you can pass all these tests, you should have little to no difficulty in transitioning to minimalism if you follow the guidelines laid out later in this chapter.

If you fail a test, that means you’re lacking that key aspect of functional strength or flexibility—that is, strength or flexibility directly related to the demands of what you’re trying to do. Your chances of getting injured while running barefoot or in minimalist shoes are greater than if you could pass the test and followed the same transition plan. If you currently fail most of the tests, then your road to healthy minimalism will be even longer.

Failing one or more of the tests, however, doesn’t mean you’re not made for minimalism. After each test you’ll see a simple exercise to improve that area of functioning. In some cases you can make dramatic improvements in as little as a week. Almost everyone can eventually get to where they can pass all the tests.

So, as of today, how ready are you to run in minimalist shoes? Let’s find out.

Testing ankle dorsiflexion.

Why test: If your Achilles tendon lacks sufficient flexibility, you not only limit your ability to push off effectively, but also increase your chance of injuring the tendon or surrounding soft tissue. This test also indicates how well your gastrocnemius (outer calf muscle) and hamstrings work together when your ankle is dorsiflexed (pointed toward your shin) and your upper back is flexed; restriction in the calves and hamstrings when the ankle is dorsiflexed will place additional strain on your Achilles tendon.

How to test: Sit with both legs straight on the floor. Lock the knee of the leg you’re going to test; keeping your leg straight fixes the hamstring at the knee and pelvis to isolate the gastrocnemius where it inserts at the heel. Loop a strap or towel around the ball of the foot to be tested. Let your thoracic spine (middle to upper back) roll forward naturally and comfortably. Flex your foot toward your shin, using the strap only to gently guide the movement.

To pass this test, your ankle should be able to flex 20 degrees toward your shin, and your upper body should be able to flex 45 degrees forward.

Stretching the Achilles and calf muscles.

How to improve: Even though the test might seem focused on the Achilles tendon, “what we need here is for the entire gastrocnemius/Achilles lever to relax, reset, and lengthen,” says Wharton. Therefore, do the following stretch, which targets both parts of the lever. It’s essentially the test exercise, but done gently and repeatedly to gradually lengthen the tissue.

Sit with both legs straight. Loop a strap or towel around the foot of the leg to be stretched and grasp both ends with your hands. Use the muscles in the front of your lower leg to flex your foot toward your knee. Use the strap only to assist at the end of the movement to get an additional slight stretch. Hold the stretch for 2 seconds and return to the starting position. Exhale as you stretch, and inhale as you return the foot to the starting position. Do 10 reps on each side daily.

Testing big-toe dorsiflexion.

Why test: An inability to move your big toe toward your shin can be an indicator of a tight plantar fascia, says Wharton. Poor big-toe dorsiflexion limits your ability to roll through smoothly to toeing off and can make your foot rotate enough to cause lower-leg injuries.

How to test: Sit with your knees bent at 90 degrees and your feet flat on the floor. Slide your hips forward so that your knees are slightly ahead of your toes. Reach down and grab your big toe while keeping the ball of your foot on the floor.

To pass this test, you should be able to raise your big toe 30 degrees off the floor without the ball of your foot coming off the floor.

Loosening the plantar fascia.

How to improve: Use massage rather than stretching to loosen the plantar fascia. Sit with one leg crossed over the other, with the outside ankle of the foot to be massaged on the other knee. Press into the bottom of your foot with your thumbs. Wherever you feel a sore spot, press down for a few seconds while flexing your toes up and down. “The massage needs to be focused pressure where you feel the microbundles of fascia release,” says Wharton. Spend a few minutes per foot daily.

Testing big-toe isolation.

Why test: About 85 percent of foot control comes from the big toe, Dicharry says. If your big toe can’t operate independently, your foot can’t properly adjust itself during the stance phase (between landing and toeing off). An unstable arch will transmit that instability up your leg. “Like the glute is the big push muscle in your hip apparatus, the big toe is the big extensor flexor for your lower leg,” Wharton says.

How to test: Stand tall but relaxed. Keep all the toes of one foot on the floor. On the other foot, press the big toe into the floor and raise your other toes while keeping your ankle stable.

To pass this test, you should be able to keep the big toe flat on the ground (instead of bending it) while you raise the other toes, and your ankle shouldn’t roll in or out.

How to improve: Increase the flexibility of your toe extensors and flexors. Sit with one leg straight and the other bent at 90 degrees. Grab the toes of the bent leg while keeping the heel on the floor. Curl your toes away from your body, using your hand only to assist gently at the end of the motion. Bring your toes back to the starting position and then curl them toward your body, again using your hand only at the end of the motion. That’s 1 repetition. Do 10 repetitions on each foot daily.

Testing ankle inversion.

Why test: If your ankle can’t move adequately toward the midline of your body (inversion) and away from the midline of your body (eversion), “you won’t utilize your arch’s shock absorber or spring to withstand the impact of footstrike,” says Wharton.

How to test: Sit with one leg bent at 90 degrees and the outside ankle of the foot to test resting just above the opposite knee. While holding that foot on the outside forefoot, rotate it inward and point the sole of the foot up.

Now bring that foot up so that it’s just in front of your butt. From the ankle, rotate the foot outward and away from your body’s midline.

To pass the first test, you should be able to rotate your foot inward 15 degrees. To pass the second test, you should be able to rotate your foot outward 5 degrees.

How to improve: Do inversion/eversion walking. First, walk like a pigeon: Turn your feet in toward each other at about 45 degrees while not bending your knees. Taking long strides, walk for 20 yards, staying on the outside of your arches as much as possible. Stop and turn around. Now walk like a duck: Turn your feet away from each other at about 45 degrees while not bending your knees. Taking small strides, walk back the 20 yards to your starting point, staying on the inside of your arches as much as possible. Do two or three of these circuits daily.

Testing ankle eversion.

Walking like a pigeon to build ankle inversion.

Walking like a duck to build ankle eversion.

Why test: Imbalances and weaknesses in your hip and trunk areas introduce instability into your gait and require your feet and lower legs to absorb more impact forces than they should.

How to test: Stand tall but relaxed with your hands on your hips. Lift one leg so that its foot is slightly below the other knee. Keep the heel and the inside and outside of the ball of the foot standing on the floor. Repeat with the other leg.

To pass this test, you should be able to hold the raised-foot position for 30 seconds while keeping your weight evenly distributed over your foot. Your leg and upper body should remain still.

How to improve: Practice the test a few times a day until you can pass it. Once you can hold the position for 30 seconds, try doing it with your eyes closed. You’ll be in for a treat!

Let’s say you’re one of the biomechanically blessed and have passed all the tests. Now you need to decide what shoe to start your transition in, and how to go about safely incorporating it into your running.

As we saw in Chapter 5, the phrase “minimalist shoe” covers a wide range of options among features like heel-to-toe drop, height of midsole, and amount of cushioning. Deciding which minimal shoe to use when starting your transition begins with the general questions noted in Chapter 5, such as whether you like a wide or narrow toebox. Once you’ve found some options within the broad characteristics you want, then you can decide how minimal a shoe to go to compared with your current one.

There are no hard-and-fast rules here. If you passed the five tests above, you could probably go right to as barefoot-style a shoe as you want, assuming you listen to your body during the transition. If your performance on the tests was shakier, you should probably consider a more gradual step down the shoe spectrum.

Another factor is your running history. If you’ve been running for only a few years and did well on the tests, you can probably handle a bigger jump down than someone who’s been running for 15 years in nothing but conventional training shoes. Your body won’t have adapted as much as the veteran’s to the altered mechanics caused by conventional running shoes. The rationale here is similar to most experts saying young runners can get away with running in less shoe because they’re starting with a cleaner biomechanical slate, as we’ll see in Chapter 8.

Also consider your typical training. If you do almost no hard workouts or races, where your feet and lower legs work through a fuller range of motion and generate more force, you’re probably not ready for as minimal a shoe as someone who regularly does faster running. Similarly, if you’re used to wearing racing flats or lightweight trainers for races and hard workouts, your Achilles, plantar fasciae, and calf muscles will be better prepared for a more minimal model than those of someone who wears more built-up training shoes for everything.

In terms of shoe features, focus on the ramp angle, or the difference in height from heel to forefoot. A good rule of thumb is to try a minimalist shoe with a ramp angle that’s about half that of your current model. To take just one example, say you know you like Asics, and have been in a traditional model like their Gel DS Trainer. It has a reported 10-millimeter heel-to-toe drop. You could try their Asics Gel Hyperspeed, which has a reported 5-millimeter heel-to-toe drop.

Of course, it’s possible to pull off a greater jump in ramp angle. In those cases, walk before you run to see how conservative a transition you should attempt. “If you’re gung-ho on going right to something like the FiveFingers, spend a day walking around in your new shoes,” says coach Jay Johnson. “For a lot of people, your feet are going to get sore afterward. That’ll give you an idea how much strength they need for you to run well in them.”

For almost everyone transitioning to minimalism, slower will get you there faster. Gradually integrating minimal shoes into your running will allow your body to adapt to the new stresses better than plunging right in. A month into the transition, you might not be running as much as you’d like in your new shoes, but 3 months in, you’re more likely to still be progressing, and running healthfully and happily, than if you switch over too quickly. What’s the rush? You have the rest of your running life to make the transition.

What constitutes a gradual transition is going to vary by runner. There are so many factors that will affect how you respond to running in minimalist shoes, including your strength and flexibility, running history, mileage, injury history, running surface, and more. This is definitely an area where the adage “we’re all an experiment of one” is true. Consider the following strategies while conducting your experiment:

The above conservative transition plan is for the vast majority of runners. A more radical mode is that advocated by Mark Cucuzzella, MD, owner of a minimalism-focused store in Shepherdstown, West Virginia. This plan entails immediately doing all your running in minimalist shoes but starting with, well, minimal mileage, such as a mile at a time. From there you gradually build to 2 miles per run, then 3 miles, and so on, until you’re back to your normal mileage in a few months. In common with the conservative transition plan, here you also spend as much of your nonrunning time as possible barefoot or in zero-drop casual shoes.

This more extreme program makes the most sense for more desperate runners. It’s what 2:37 marathoner Camille Herron, whom we met in Chapter 2, did after suffering seven stress fractures in a few years. The thinking here is that if you’re chronically injured in regular running shoes, you need a more dramatic change in your routine. Once you’re over your latest injury and are ready to resume running, make minimalist shoes an integral part of your new running life from the get-go, Cucuzzella advises. Of course, you don’t have to be returning from injury to take this approach, but few healthy runners are willing to go cold turkey on mileage simply for the sake of adapting to new shoes.

Counterintuitive though it might seem, the best shoe for this approach is often a more minimal model than when transitioning gradually. You’re essentially starting your running program from scratch. So your mileage will be quite low for some time, and your body should be able to handle the small amount of running you’re doing even in a zero-drop, minimally cushioned model. With that safety factor built in, it makes sense to attempt to rewire your running mechanics in a shoe that allows for the most natural gait.

Most runners are going to feel muscular aches in the early days of their transition to minimalist shoes. Unfortunately, some will experience more acute injuries, despite carrying out what seemed like a conservative plan. As Wharton explains, those minimalism-specific injuries are predictably from the knee down.

“As the heel has to drop, you’re going to utilize a lot more of the calf unit, the gastrocnemius and soleus,” he says, “and you’re stretching the Achilles a little bit more, which is great long-term, but at the beginning it’s really tough because you’re not getting help from other muscles in close proximity on the kinetic chain. There’s a lot more responsibility on these lower-leg muscles. So we get a lot of posterior tibial problems, tendinitis and ligament strains, peroneal tendon pain, even fractures.”

Here are the three most common injuries runners encounter while transitioning to minimalist shoes, and what to do about them. In all these situations, once you have the acute phase under control, reboot your transition to minimalism by starting from scratch instead of diving back into where you were when you got injured.

The plantar fascia is a thick, fibrous band of connective tissue that supports the arch. Running in a shoe with a lower heel and running with more of a midfoot strike require the plantar fascia to absorb more impact forces. “The arch was designed as a spring, and if that spring isn’t strong and flexible, then you’re not going to be able to translate the shock of running to a specific mechanical change,” says Wharton. Many runners have tight, weak plantar fasciae from decades of wearing shoes with heels, both while running and in daily life. A dramatic increase in the plantar fascia’s workload can lead to almost immediate injury.

You’ll feel a sharp, tearing pain along the inside bottom of your foot anywhere from the heel through the arch. Many times, the pain is the worst when you step out of bed in the morning or when you’ve been sitting for a long time; it tends to lessen with mild activity but then be present after you run.

You can usually run through plantar fasciitis, but you need to protect the fascia while it’s inflamed. That means returning to conventional shoes until the pain subsides. Rolling your foot along a glass bottle you keep in the freezer provides a simultaneous icing and massage. Anti-inflammatories such as ibuprofen can also help to calm the fascia.

The Achilles tendon is key to running with a midfoot landing and push-off. Like the plantar fascia, in most modern runners the Achillies has been shortened and weakened by elevated shoes for running, work, and leisure. So, like the plantar fascia, it’s easily overloaded if you suddenly start running in shoes with a minimal ramp angle. Bloodflow to the tendon is relatively poor; the tendon is slower to warm up than some other key running body parts.

Like plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinitis produces a sharp, tugging sensation, in this case from the back of your heel up to the bottom of your calf muscles. In severe cases, you’ll be able to see swelling. Unlike with plantar fasciitis, the pain tends to get worse, not better, with running.

Icing and anti-inflammatories can help to reduce the inflammation. Mild stretching—never to the point of producing pain—can help increase bloodflow to the tendon. You can try to run through Achilles tendinitis in your conventional shoes, but unless you want it to drag on forever, you’ll need to lower your mileage dramatically, do nothing but run slowly, and avoid hills as much as possible. If the tendon is so aggravated that it’s noticeably larger than your healthy one, you’re usually better off not running until you get the most severe inflammation under control.

Running in minimalist shoes often reveals underlying weaknesses throughout the body. In many runners, says Wharton, “a lot of the muscles that are supposed to be doing their job, like the glutes, hamstrings, hip rotators, and iliopsoas, aren’t doing their jobs. This tends to lead to a harder footplant.” Conventional running shoes tend to accommodate this form flaw better than minimalist shoes, thanks to plush cushioning. With less material between you and the ground, running in minimalist shoes puts more of the impact force from bad form on the bones of your feet, especially the metatarsals, the five long bones running from midfoot to the base of the toes.

Stress reactions are precursors to stress fractures. Initially you’ll feel a dull ache over a small area in the front or middle of your foot. As with most stress reactions and fractures, pressing on the sore spot will likely cause pinpoint pain. Although you may have heard that you can’t run on a stress fracture, we runners are a tough, dedicated bunch, and it’s possible to run on a fractured foot, at your normal mileage, no matter how ill-advised doing so is. If the pain is worse after you run, then you’re well along the path of a stress reaction becoming a full-blown fracture.

Although you can run on a stress fracture, you shouldn’t. There’s no finessing your way through the process of getting a weight-bearing bone to heal. Metatarsal stress fractures usually require 1 to 2 months of no running for proper healing. If you’ve caught the problem early (you can produce pinpoint pain by pressing, you feel it when you run, but it’s not worse hours after a run), then you can get away with less time off. But as with transitioning to minimalist shoes, a little more conservatism in the short run can lead to fewer setbacks a couple of months down the road.

Let’s say you’ve successfully transitioned from a conventional training shoe into one of the gateway minimalist models like the Saucony Kinvara, or even something more minimal. Should you keep moving through the minimalist spectrum to a lighter, lower shoe? Should everyone’s goal be running solely in barely there shoes or barefoot?

As with so much in running, there are no universal answers here. Start by remembering that minimalist shoes are a means to the goal of better running form. They’re part of a tool kit that, ideally, also includes core strength and functional flexibility, training at a variety of paces and being at a good running weight, and other factors that contribute to being a healthy, efficient runner. We can all run with better form in whatever shoes we have. Focusing only on the ramp angle and stack height of your shoes is, frankly, being irresponsible. “You can’t just get to a certain point and say, ‘Okay, I’ve got these shoes that are a 6-millimeter drop, I’m running a little better, but I just don’t feel like doing drills anymore,’” says Brian Metzler, coauthor of Natural Running. “You’ve got to keep it up and do everything across the board.”

Minimalist blogger Larson says, “I wouldn’t say, ‘You’re in the Kinvara now, so you have to go down to something like the New Balance 1600 [a light racing flat].’ I think that’s what some people do. They feel like, ‘I have to continue this progression until I’m running in nothing.’

“That doesn’t have to be the end point. When the Kinvara came out, I was talking with one of the guys from Saucony, and he was telling me they have this internal debate about that—what do you tell people? Is this an end-point shoe or a gateway shoe? My response is it could be either. You need to decide that for yourself.

“Initially my own goal was ‘Maybe I should be doing all my running in something like the Vibram FiveFingers,’” Larson continues. “I’ve come back to the realization that wearing a shoe with a little bit of cushioning is not an evil thing if it allows you to run the way you want to run.”

That last point is key. Just as there are other aspects of running with good form than your shoes, there are other aspects of running than your form. “Of course running form is important,” says Joe Rubio, who coaches several national-class runners in California. “But to think about it all the time . . . sometimes you just want to go for a run, you know?”

“That’s especially true on the trails,” says Metzler, who was the founding editor of Trail Runner magazine. “Depending on the trails and shoes, you can run as nimbly as possible but still feel every pebble, stalk, or notch on the trail. To go through a whole run like that isn’t always the most enjoyable thing to do.

“But even on the roads, there are a lot of obstacles out there, whether it’s stepping off a curb or on a pebble,” Metzler continues. “Do you want to have every step of the way be this aware, eyes-on-the-road thing, or do you just want to run and zone out? I think for most runners there’s a happy medium where you’re in a shoe that promotes good form but also offers enough protection so that most days you’re just running and not thinking about your shoes and form the whole way.”

If, for most runners, the transition to minimalist shoes doesn’t necessarily mean running in as little as possible, where does that leave barefoot running? Is there a role for running without shoes in most runners’ programs? The answer is yes, and that’s the subject of the next chapter.