ALMOST ALL RUNNERS hope to run for the rest of their lives and to never be injured while doing so. Working toward that ideal is probably your main motivation for running in minimalist shoes. This chapter is about what you can do to marry minimalism with a lifetime of running.

First we’ll see how to do some key exercises that help you run with good form in any shoes, but especially in minimalist shoes. Then we’ll learn a few drills that will help hardwire improved form into your daily runs. We’ll see what to do when not running to best preserve your running body, and consider whether minimalism is right for runners of all ages. We’ll end by addressing this question: Should you commit to doing every run for the rest of your life in minimalist shoes?

“If you want to become a better runner, begin by running better,” says Pete Magill, a California coach and the oldest American to break 15:00 for 5-K, which he did a few months before his 50th birthday.

By that Magill means doing things that improve your ability to run more efficiently and with good form. Learning to run well in minimalist shoes is one means toward that goal. But for almost all runners, switching shoes isn’t sufficient. Typical Western lifestyles, with lots of time spent sitting and little time spent doing a wide variety of activities that work the whole body through a variety of motions, make many of the muscles needed to run with good form weak and tight.

Put another way, all modern runners should consider regular bodywork integral to their running, not something only elites who have all day to train or people returning from injury do. Consider strengthening key running-specific muscles as both a performance enhancer and a form of insurance. “Any runner, no matter what shoe they wear, if they want to do one thing to try to prevent injury, I would recommend targeted strengthening,” says sport podiatrist Brian Fullem.

Minimalist runners are especially good candidates for this work. As we saw in Chapter 6, weakness and/or tightness in key lower-leg muscles and your core can increase your risk of injury when you start running in minimalist shoes. What you need in these areas is functional strength and mobility—that is, strength and mobility to meet the specific demands of maintaining good running form and being resistant to injury. “Sorry, but these aren’t your beach muscles,” says physiotherapist Phil Wharton. “A lot of them are tiny muscles no one’s ever going to see, but that absolutely need to be functioning to run with good form in minimalist shoes.”

Although we tend to focus on the lower legs when we talk about the requirements of running in minimalist shoes, core strength—in your hips, glutes, lower back, and abdomen—is vital. Good core strength will help you maintain a stable pelvic position while running, saving your lower legs from getting overloaded by the impact forces of running. If you notice that you start runs with good form when wearing minimalist shoes but then get sloppy after a few miles, that’s an indication that you need to improve your core strength.

The following exercises strengthen and improve flexibility in the key running muscles in your feet, legs, and core that contribute to good running form. Do this group of exercises at least twice and preferably three times a week. The whole set won’t take you longer than 15 minutes and makes for a nice postrun routine. If you’re motivated to go beyond the exercises here, Wharton (whartonperformance.com) and coach Jay Johnson (runningdvds.com) have excellent, extensive resources in the form of books, DVDs, and short instructional videos.

Why: This exercise strengthens your lower-leg muscles and the muscles that support and form your arch.

How: Stuff a 1- or 2-pound weight into the toe of a long sock. (Finally, a nonembarrassing use for compression socks!) Place the sock between your big toe and second toe with the weight dangling under the ball of your foot. Make a stirrup by wrapping the end of the sock around the outside of your foot, under your arch, and back up over the top of your foot. Fasten it securely by tying under the top wrap.

Sit on a high enough surface so that the weighted sock doesn’t touch the floor, with your back straight, your knees slightly apart, and your lower legs dangling. Point your foot down so that your big toe is pointing at the floor. Sweep your foot up and toward the midline of your body, pointing your big toe to the ceiling. Pause, then sweep your foot back down to the starting position, with your big toe pointing straight down at the floor.

Without pausing, sweep your foot up and away from your body as far as possible. Slowly return to the starting position. Imagine the full movement forming a U in the air. The whole pendulum sweep should take you about 8 to 10 seconds. Do 10 full sweeps (10 in each direction). Repeat on the other foot. Do two sets of 10 for each foot. (For convenience’s sake, consider getting enough weights to have a weighted sock wrapped around each foot.)

Over time, you can add more weight to the socks. Don’t add so much weight that the sweeping movement becomes strained. It should feel like a good assisted stretch, not a taxing weight-lifting movement.

Why: This exercise strengthens your soleus, the calf muscle that’s the main supplier of blood to your lower legs, ankles, and feet.

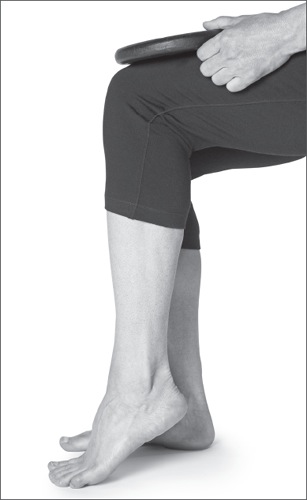

How: Sit with your legs bent at 90 degrees and your feet flat on the floor. Place a weight on top of one knee. The weight should be heavy enough so that you feel the soleus working when you do this exercise, but not so heavy that your calf is sore after. When in doubt, start with a lighter weight.

Keeping your toes on the floor and your knee bent at 90 degrees, raise your heel as far as you can by pushing up with your toes. Take 2 to 3 seconds to go up and another 2 to 3 seconds to come down. Do 10 reps, switch the weight to the other leg and do 10 reps, and then do another set of 10 reps with each leg.

Over time, add more weight.

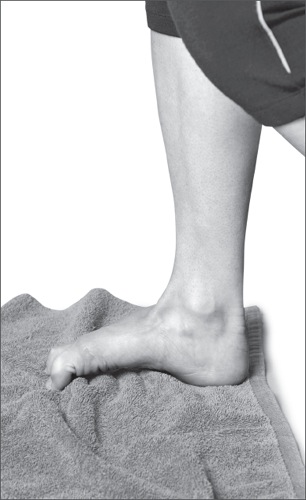

Why: This exercise strengthens your medial and lateral arch, especially the medial (inside) arch.

How: On a slick surface such as a wood or tile floor, place a towel so that the short end is in front of a chair you’re sitting in. Sit straight with bare feet and with your legs bent at 90 degrees. Place your foot on the edge of the towel; throughout the exercise, keep your heel flat on the towel. Using only your foot muscles, reach out with your toes and contract them to grab a bit of the towel and pull it toward you. Concentrate on spreading your toes as you pull the towel toward you. Do 10 pulls, then straighten the towel to the starting position. Do another set of 10. Repeat with your other foot.

Once you’ve mastered regular towel pulls, make them more challenging by placing a small weight on the middle of the towel.

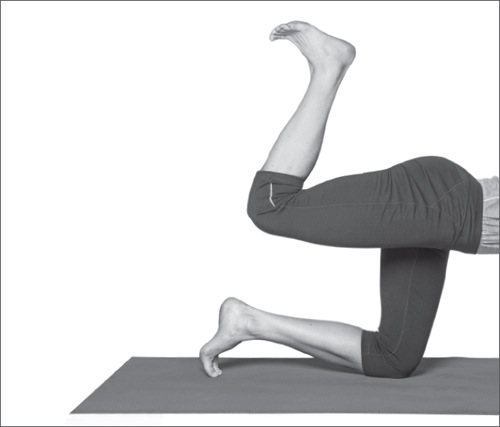

Why: This exercise strengthens your glutes and hip rotators. Better strength in these crucial core muscles will lessen common form flaws like splayed feet, an uneven pelvis, excessive lateral rotation, and leaning forward at the waist.

How: Lie on your left side with your legs together and bent at a 90-degree angle. Hold your arms together, extended in front of you. While keeping your feet together and your left leg on the floor, lift your right knee as if your legs were an open clamshell. Do the movement slowly—2 to 3 seconds going up, 2 to 3 seconds coming down—rather than rushing through as quickly as you can. Do 10 reps on that side, then switch sides and do 10 with the other leg.

Over time you can make the exercise more challenging by attaching a Theraband around your legs near the knees.

Why: This exercise will dramatically increase range of motion in your hip joints.

How: Start on your hands and knees on the floor, hands under your shoulders, knees under your hips. Keeping your right knee bent at 90 degrees, lift your right leg and lead with your knee moving forward to sweep the leg in a circular motion. Ideally your knee will come near your hip at the top of the circle. Do 10 forward circles, return to the starting position, and do 10 backward circles. Backward circles will probably be more challenging. Repeat with the other leg.

Why: In its three variations, this exercise strengthens the small stabilizing hip and butt muscles, especially the gluteus medius.

How: Lie on your left side with your legs extended out straight. Your left arm can rest under your head; your top arm can rest on your hip. With your right foot parallel to your left foot, lift your right leg. Keep your hips steady and facing forward. Lower the leg. Take 2 to 3 seconds to go up and 2 to 3 seconds to come down. Do 5 reps with your right foot in this neutral position. Then maintain the original position except turn your right foot out so that the toes point toward the ceiling. Do 5 reps in this position. Finally, maintain the original position except turn your right foot in so that your toes point toward the floor. Do 5 reps in this position. (This last position will be the most challenging for most runners.) Do the same sequence of five reps in each of the three foot positions with the other leg.

When you can do all three positions without your working leg shaking, make the exercise more challenging by wearing ankle weights.

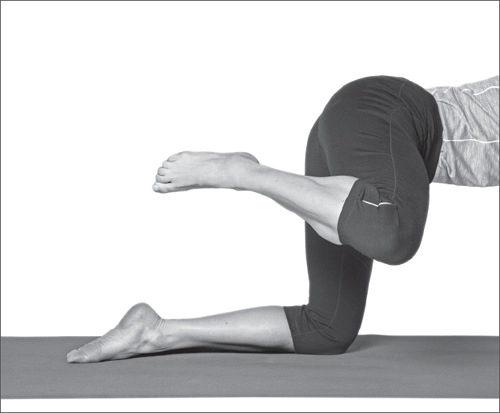

Why: This exercise strengthens your glutes, thereby enhancing your hip extension.

How: Start on your hands and knees on the floor, with your back straight but relaxed. Your hands should be under your shoulders, and your knees should be under your hips. Keeping your right knee bent, kick your right foot back and up so that the bottom of your foot faces the ceiling and then, without pausing, moves toward your back like a hook. Keeping your knee bent, return to the starting position and then move past it so that your knee nears your chest. Do 10 times with each leg.

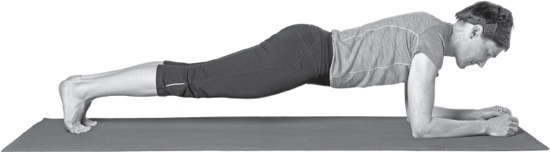

Why: This exercise strengthens your deep abdominal muscles. (You may have heard it and the other pedestal positions that follow called planks.)

How: Balance on your forearms and toes on the floor. Your elbows should be bent at 90 degrees and your toes should be slightly dorsiflexed (pointing up). Keep your shoulders, neck, and head stable but relaxed; don’t scrunch up your shoulders or place all your weight on your elbows. Keep a straight line from your shoulders to your ankles. Concentrate on keeping your hips level, neither sagging toward the floor nor elevated so that your butt points up. Hold for 30 seconds.

Over time increase to holding for 60 seconds.

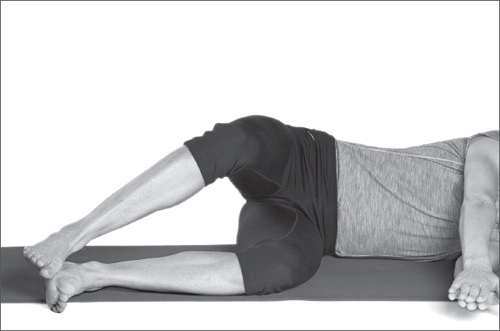

Why: This exercise strengthens your hamstrings, glutes, and lower-back muscles.

How: This is basically the flip side of the prone pedestal position. Balance on your elbows and heels, belly button pointing up. As with the prone pedestal, keep a straight line from your shoulders to your feet. Tuck your chin slightly toward your chest. Hold for 30 seconds.

Over time increase to holding for 60 seconds.

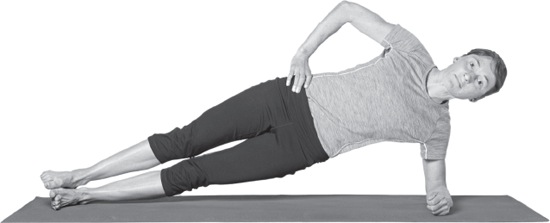

Why: This exercise strengthens your lower-back and side abdominal muscles.

How: Balance yourself on your left elbow and your feet, with the right foot stacked on top of the left foot. Place your right hand on your waist. Your left elbow should be under your left shoulder, with plenty of space between your left shoulder and head. Keep a straight line from your right shoulder to your feet. Don’t allow your hips to drop. Hold for 30 seconds, then repeat on the other side.

There are several ways to make this exercise more challenging. First, increase to holding for 60 seconds. Then switch to balancing on your hand instead of your elbow. In that position, the closer you keep your top arm to your body, the more difficult the side pedestal will be. Finally, you can progress to doing side pedestals with your eyes closed.

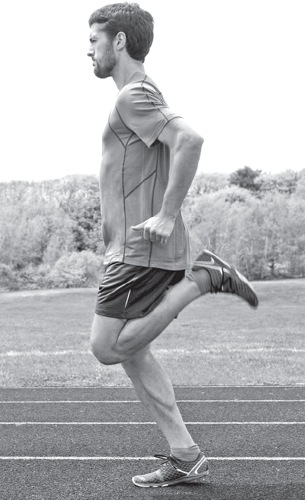

Most elite runners do drills at least a couple of times a week. Most recreational runners don’t. That’s a shame, because devoting just a little time each week to these exercises has so many benefits—you’ll recruit muscle fibers needed to run with your best form, correct muscle imbalances, become accustomed to moving through a fuller range of motion, and retrain your nervous system. These gains will help you run with better form at all speeds.

Runners moving to minimalist shoes are especially good candidates for drills. Remember, minimalist shoes are a means to the end of running more efficiently and effectively. Drills are another means toward that goal of improved form. Refining your running body with drills will make it easier to hold the improved form you’re hoping to achieve by running in minimalist shoes.

Do drills at least once and preferably twice a week. When you’re new to drills, do them after one of your easier runs of the week. As you get used to doing drills, you can do them pretty much any day. Many competitive runners include drills as part of their warmup before races and hard workouts, to help prime their bodies to operate at peak capacity.

You can do drills anywhere you have a flat, level surface for 30 to 50 yards—road, track, grass. Drills on a grass field feel good, but make sure there aren’t divots or other hazards waiting to trip you up. In terms of convenience, your street is a great venue if it doesn’t have a lot of traffic—you finish your run, do your drills, then head in for the day. And the neighbors will enjoy watching you.

There are an infinite number of drills you can do. The six that follow complement each other by working key aspects of having and holding the form you’re trying to attain by running in minimalist shoes. If you’d like to learn more drills, I recommend DVDs put out (separately) by Johnson and another coach, Greg McMillan.

Do these drills in your minimalist shoes or barefoot. Complete each drill twice. Perform the drill as described, turn around and jog back to the starting point, then turn around again and run fast but relaxed over the same stretch. Adding that quick strideout (not a sprint!) after doing the drill will help to hardwire the movement pattern into your form. After doing the strideout, walk back to the starting point or walk around the area where you finished long enough so that you’re sufficiently recovered to do the next drill with good form. Your heart rate can get quite high in the short term while you’re doing the drill and postdrill stride; allow it to lower before starting the next drill. After you’ve done the drill and postdrill strideout the second time, recover, then move on to the next exercise.

The order of the drills moves from gentlest to most challenging in terms of dynamic range of motion.

Why: This exercise activates the hamstrings and glute muscles so that you become more accustomed to using them to power the swing phase of your stride; the result is a stronger, more flowing stride than when you rely on the flexor muscles, such as the quadriceps, along the front of your body.

How: While staying on your forefoot, bend the leg you’re going to lead with at the knee. Use your hamstrings and deep buttock muscles to extend that leg behind you. Walk backward as you continue to contract your glutes. Take long walking strides while keeping your upper body upright but relaxed. Cover 30 yards.

Why: This exercise will help improve your stride frequency by getting your nervous system used to firing more quickly. The shuffle can also help reduce a tendency to overstride. Finally, it works the peroneal muscles, on the outside of your lower legs; better activation of those muscles will help you get off your toes more quickly and with more power.

How: Staying on the balls of your feet, shuffle forward as quickly as you can while skimming over the ground just inches at a time. Keep your knee lift at a minimum. Keep your arms bent at a 90-degree angle and loose, and your torso upright and relaxed. Cover 10 yards. Proper recovery between drills is especially important with this exercise, so that your nervous system can fire as quickly as possible.

Why: This exercise will teach you how to get off the ground more quickly, thereby improving your stride rate and lessening the amount of time you spend in the stance phase of the running gait. It’s especially helpful for runners whose feet splay out as they toe off.

How: Stand with one foot flat and the other leg bent at a 90-degree angle, with your arms in the appropriate corresponding positions. As quickly as possible, do an “exchange,” getting into the same position on the other foot. While learning to do the drill, focus on doing 10 exchanges with the best balance possible. As you become better at the drill, see how many you can do with good balance in 15 seconds.

Why: This exercise helps to lessen the time it takes to bring your foot up and behind you after you toe off. It also teaches you to use your calf muscles more at toe-off and to keep your trail leg close to your backside rather than extended far behind you. Finally, it improves driving your arms quickly in sync with your legs.

How: While staying on your toes with your ankles dorsiflexed (feet pointed toward your shins), quickly snap your feet back to kick your butt. The first few times you do this drill, you might not be able to reach your butt; you should be able to with practice. Keep your head up and over your shoulders, and keep your upper body erect but not overly stiff. Although you want the foot-to-butt motion to be quick, don’t worry about how swiftly you’re moving across the ground. Cover 30 yards.

Why: This exercise works your quadriceps and hip flexors so that your knee lift is greater and more efficient.

How: Use a pistonlike motion to rapidly lift your knees and drive your toes back toward the ground. Stay on your toes throughout the drill. Hold your arms straight out in front of you as if you’re carrying a pizza box; imagine trying to keep the box flat. It’s okay to lean back a little if that helps with your knee lift. Cover 30 yards.

Why: This exercise works full range of motion in your hips.

How: If you’re new to this drill, do it walking your first few times. Walk sideways, bringing your right foot in front of your left foot, then your right foot behind your left foot, repeating this pattern for 20 yards. Turn around and continue to walk sideways in the same direction, but now leading with your left leg—left foot in front of right foot, then left foot behind right foot, again repeating the pattern for 20 yards.

As the movement becomes familiar, convert the walk into a skip. Move laterally while swiveling your hips and swinging your arms across your body, alternately moving one leg behind your body, then bringing it across the front and lifting your knee high in the front swivel. Do 20 yards focusing on one leg, then turn 180 degrees and focus on the opposite leg for another 20 yards.

Over time the movement will feel more natural and you can concentrate on increasing the speed of the lateral skip and the distance you travel with each stride.

With age, many of us become increasingly removed from regularly moving through all planes of motion, as children tend to do while playing and participating in a wide variety of games and sports. At the same time, we tend to spend more and more time sitting, either in a car or at a desk. In the latter case, we’re often slumped in front of a computer, perhaps with our head bent down and/or thrust forward.

None of this is good for our running form. Former Olympic marathoner and current office worker Pete Pfitzinger says that sitting all day at a desk means “the hamstrings become short and weak and the core muscles do not have to work as you lean back in your chair.” Magill says, “It plays murder on our hips, and can also cause iliotibial band syndrome. Anything we do for a long time strains certain muscles, and they’re going to go into spasm.” Veteran coach Roy Benson adds, “As we spend less time being active and more time being passive, like sitting at a computer, even though we run, the less control we have of our skeleton by our muscular system, and that is a big problem.” Wharton describes the effect of the sitting most of us do as “glutes in hibernation”—what should be the powerful muscles in your butt and hamstrings are rarely activated. Over time you lose the ability to use them effectively when running.

There are two modes of attack here—address the problems and prevent the problems. Addressing them includes regularly doing the strengthening exercises and drills outlined above. In addition, if you run after work, undo some of the day’s damage with a dynamic warmup (leg swings, plus the milder drills, like backward walking) that will activate your running muscles and help you start the run with better form.

In addition to regular strengthening work, much of prevention comes down to day-to-day habits. Set up your monitor or other workstation so that it’s at eye level. Move your monitor close enough so that you’re not straining to see it (and therefore thrusting your head forward). Position your keyboard so that your elbows are bent at 90 degrees to minimize strain on your shoulders. When your shoulders and neck are tight and out of alignment, they’ll throw off your hips, and your running form will suffer.

Sit with your center of gravity over your hips and your feet flat on the floor. Angle your chair so that your knees are slightly lower than your hips. (As much as possible, try to achieve the same posture while driving.) And no matter how good your sitting posture is, get up and move around at least once an hour to undo some of the chronic low-level strain on your shoulders, neck, and head.

Then there’s the matter of what’s on your feet during the vast majority of your life when you’re not running.

Kevin Kirby, a sport podiatrist and marathoner in northern California, believes minimalists would do well to think about more than just their running shoes. “They are so worried about everyone’s extra 8 millimeters of heel height during their 30- to 60- minute runs, but are saying nothing about the health effects that wearing shoes with 75 millimeters of heel height and overly tight toe boxes for 8 hours per day has on a woman’s feet, knees, and lower back.”

A British study published in 2010 documented the structural changes that high heels cause. It measured gastrocnemius length and Achilles tendon agility in women who regularly wear high heels versus women who don’t. The heel wearers’ calf muscles were about 12 percent shorter, and their Achilles tendons were more than 10 percent more rigid than those of the women who wore flat shoes. As a result, the heel wearers had significantly less range of motion in their ankles.

A Finnish study published in 2012 showed how these sorts of structural changes have functional implications. Researchers gathered two groups: one made up of women who had worn heels of at least 5 centimeters for 40 hours a week for at least 2 years, and the other made up of women who wore heels for less than 10 hours a week. While the women walked over level ground, the researchers measured ankle and knee motion and lower-leg muscle activity. The heel wearers had measurable increases in fascial strain and muscle activity compared with the other group. Their history of wearing heels for much of the workweek had altered their basic walking mechanics. While the study looked at the effect of heels on walking, not running, it’s reasonable to think the mechanical deficiencies would be that much more amplified when running.

Wearing flat shoes and going barefoot in sedentary hours is a key part of the transition-to-minimalism plan we looked at in Chapter 6. Continuing that practice is a key part of maintaining your running body. If heels are unavoidable in your profession, do the best you can to minimize the time you spend in them, such as wearing other shoes while commuting and taking the heels off when you know you’ll be at your desk for a while.

Parents used to be told their children should wear “supportive” shoes to help young feet adapt properly to increased activity. Fortunately, that thinking has been set aside by knowledgeable people. In running terms, most experts agree that young runners are ideal candidates for minimalist shoes, both because of less initial injury risk and because of the long-term gains to be had.

“I would encourage it for any adolescent,” says Fullem. “My 10-year-old son just ran his first 5-K, and I try to get him in as minimalist a shoe as possible. I think if you start with the younger kids, their muscles and their tendons and everything get stronger.”

“I think the high school kid should maybe push the envelope a little bit more in terms of minimalism,” says Johnson, who conducts annual high school running camps in Boulder, Colorado. “I think sometimes kids get sold shoes that are made for heavier, middle-aged people training for a marathon when they’re a light, waify kid whose longest race is 5-K.” The “protection” that “supportive” shoes traditionally were said to provide should come via the strengthening work laid out earlier in this chapter, says Johnson.

Young runners have less injury risk running in minimal shoes because they haven’t done years of mileage in bigger shoes that alter their mechanics and weaken and tighten key running muscles. For the same reason, they’re also ideal candidates for extensive form work, says Steve Magness, a former coach with the Nike Oregon Project who’s also worked with leading high school runners.

“They don’t have years of ‘This is how my running form is,’” Magness says. “It’s not ingrained as motor programming like with someone who’s been running a long time. They’re much more of a blank slate and easy to change with low risk.” As Magness points out, young runners usually aren’t doing much mileage, making their situation analogous to the start-from-scratch transition plan we looked at in Chapter 6.

“I’d generally go with a lightweight trainer for most high school kids,” says Magness. “Not something crazy minimal, but more like what older runners might wear for long tempo runs and marathon-pace runs.”

Johnson thinks that young runners will benefit from minimalism not only now, but also when they’re adult runners. “We’re at a really cool time in our country where kids are into the sport and the shoe companies are putting out ‘less’ shoes,” he says. “I think we can have kids have fewer injuries in the next 10, 20 years as long as they’re doing the strengthening work as well.”

At the other end of the age-group spectrum, don’t be dissuaded from running in minimalist shoes simply because you’re middle-aged or older.

“All other things being equal, if you’re an older runner, you should have better bone density than a sedentary person of your age,” says Fullem. “It’s known as Wolff’s Law—your body responds to the stress of the pounding by strengthening the bone.” You shouldn’t be at a higher risk of stress fractures than younger runners from running in shoes with less cushioning.

If you’re a new runner in your 40s or older and have been sedentary most of your life, then it’s a good idea to have your bone density checked regardless of what shoes you run in.

As we saw in Chapter 6, younger new runners can sometimes transition to minimalist shoes quicker than their contemporaries who have run for many years. If you’re an older new runner and your bone density is good, you should be able to use minimalist shoes as one of your footwear options without undue concern for getting a stress fracture.

You’re probably familiar with the fact that it’s easier to maintain fitness than to obtain it. That principle also applies to improvements in your running form—once it’s gotten better because of minimalist shoes, strengthening exercises, and drills, it’s easier to run with good form in whatever shoes you wear. Certainly that’s the experience of elite Kenyans, who grow up covering lots of miles in little or no shoes, and then maintain beautiful form once they start running in conventional shoes.

Of course, you need to be diligent about the strengthening work and form drills, especially if you have a typical Western lifestyle. But running in minimalist shoes isn’t an all-or-nothing matter any more than most other aspects of running are. If you enjoy doing all your running in minimalist shoes, great. If you enjoy running in minimalist shoes and more conventional models, feel free to do so. You won’t be kicked out of any club (at least any worth being part of). And you’ll be putting into practice what successful runners have long done—rotating shoes.

Joe Rubio, coach of the Asics Aggies and a 2:18 marathoner at his prime, says, “I’ve been coaching a long time, and 80 to 85 percent of the people are going to have the most success alternating different shoes for different purposes. When I was really racing, you had spikes for really fast stuff, a really light pair of racing flats for 5-K race-pace workouts, a little more substantial shoe for tempo runs, a lightweight trainer for most of your regular runs, and a padded pair of bricks for your true recovery days, because you wanted to run slow and not take the pounding. And you did your barefoot strides.

“It’s like interval training back in the ’60s—you did it every frickin’ day!” Rubio continues. “It worked for some people, but it didn’t work for a huge number of people. In my mind, it’s the same thing with real minimalist shoes. Some people can train in them for everything and be fine, but most people are going to do better by picking certain days to train in that type of footwear. They’ll still get the advantages.”

Many runners find that once they’ve become accustomed to running in less shoe, they no longer enjoy running in traditional trainers. (I’m one of them.) If that’s you, consider rotating shoes within the minimalist spectrum. Popular minimalist blogger Peter Larson says, “If I had to pick three or four shoes, I’d probably want something with maybe a 4-millimeter heel rise and some decent cushioning for longer runs; a racing flat; something that has no cushioning as a training tool and for form work and shorter runs; and a trail shoe.”

Larson, who teaches college courses in anatomy, points out a key value of shoe rotation beyond the performance aspects Rubio outlined above.

“If you ask me why injuries happen, I think it’s because we run lots of miles on terrain that doesn’t vary at all,” Larson says. “And that’s not necessarily because it’s hard, but we go out and run on the road and there’s no variation and we pound our legs in the same shoes on the same runs every single day and there’s no variability. I haven’t seen any studies comparing injury rates in trail runners versus road runners, but running on trails varies things. If you want to try to get that variation on the roads, running in a few different pairs of shoes might be one way to do that.”

If you find you’re a happy, healthy runner doing all your mileage in minimalist shoes, great. If you find you’re a happy, healthy runner doing two runs a week in minimalists, or somewhere between that and all your running, that’s great, too. There are no rules you have to follow about how often to wear minimalist shoes. Five years from now, you’re more likely to be a healthy runner enjoying your sport if you avoid extremes and rigid but arbitrary standards. That applies to mileage, diet, competitive goals, stretching and strengthening, and pretty much everything else, including what shoes you choose to run in.

Five years from now, if you’ve made minimalism part of a sustainable approach to your running, what will your minimalist shoe choices be? That’s the subject of our final chapter.