2

The Language of Citizenship

Compatriotism and the Great Antillean Fires of 1890

In the rising swelter of the tropical summer, a fire rampaged through the heart of Martinique’s capital city, Fort-de-France. The trade-wind-fueled blaze incinerated sixteen hundred homes, destroyed 1,018 nonresidential properties, killed thirteen people, and left six thousand people—half of the city’s population—without food, water, shelter, or clothes. Nearly three-quarters of the city lay in ruins.1 In addition to the human and physical costs, the economic costs were staggering. With the total damage estimated at between fifty million and sixty-seven million francs, the destruction was more than ten times Martinique’s yearly budget, and the blaze consumed all the capital and assets that kept La Société Mutuelle—the city’s primary insurer—solvent. The homes alone were valued at over fifteen million francs.2 Guadeloupe’s governor, Antoine Le Boucher, exclaimed a day later, “Fort-de-France no longer exists! A terrible fire has completely destroyed it.”3 The embers in Martinique had not yet cooled when the town of Port-Louis on Martinique’s sister island of Guadeloupe went up in flames a week later, destroying sixty-eight homes, burning down three-quarters of the town, and, according to the French National Assembly, “plunging another 4,000 inhabitants into misery.”4

These fires—along with a litany of hurricanes, earthquakes, and disease epidemics, as well as the catastrophic eruption of Mount Pelée in 1902—furthered the commonplace French view that the Caribbean was a volatile, exotic environment that perpetually threatened to annihilate those living there. Nevertheless, this distant and dangerous locale held a special place in the French imagination. Not only had it been under French control since 1635—longer than many parts of the metropole (Nice, Savoy, and Alsace, to name a few)—the ideal of colonial assimilation had been made good in the form of full citizenship rights. As a result, French Antilleans demanded a quality of life equal to that of their metropolitan counterparts.

Given the sad social conditions of so many French people within the metropole, Antillean citizenship may have been worth little. A governmental report in 1881, for instance, demonstrated that 85 percent of Frenchmen in the Haute-Loire department were either indigent or completely destitute.5 Meanwhile single parents headed more than one-third of all French households in 1900, as late industrialization dislocated communities and debased workers in an inequitable labor market.6 The republican universalist virtues of liberty, equality, and fraternity projected the battle cry of a French Republic that sought to rectify inequality in all its forms, but they also conjured the sarcastic lament of a citizenry that, in its endeavor to create a social republic where one did not yet exist, experienced what Eugen Weber described as the “internal colonization” of a nation being knitted together by railway lines and coal mines—the groan of a citizenry under the yoke of unfair labor practices, dangerous working conditions, and a destitute standard of living. As full French citizens, Antilleans should be situated as active participants in the social and cultural developments of a turn-of-the-century France riddled with social cleavages, labor unrest, and, to some extent, a delusional sense of optimism undercut by a pervasive fear of cataclysm on the horizon.

The great fires of 1890 and the French government’s relief campaign illustrated to contemporaries the French state’s need to safeguard its Antillean citizenry. In exploring the duty incumbent upon the state to safeguard the French citizenry at large, including those living in the remarkably un-French environment of the tropics, this chapter examines the way in which the 1890 fires in the Antilles resonated throughout the metropole. Viewing the people living there as inherently French—“more French than the French,” as many say today—Frenchmen met the dire situation following the great fires of Fort-de-France and Port-Louis with an outpouring of public support from all across France and a call for everyday compatriots to open their wallets to their brothers in peril.

This chapter begins with a discussion of the Fort-de-France and Port-Louis fires, their causes, and the way in which contemporaries in the press and government interpreted the virtual annihilation of Martinique’s capital city and Guadeloupe’s plantation town. Then it describes the subsequent relief campaign orchestrated by the French government, with an eye toward what that campaign tells us about the cultural place of the French Antilles in the French Republic. The third part of the chapter looks at a disaster within the metropole itself—a mine collapse at Saint-Étienne—that was not only contemporaneous with the fires of Fort-de-France and Port-Louis but also analogous in many ways. Analysis will show that victims on both sides of the Atlantic occupied similar places in the French imagination. While racism undeniably underlay the French understanding of these great disasters, classism and elitism were just as important to understanding how the French treated their Antillean compatriots. By looking at a mine collapse at Saint-Étienne in southeastern France, we can see that race was mapped onto class, and that class was understood as a racial concept.

Fort-de-France: “A Town of Silent Ashes”

The geography of the Caribbean presents a unique confluence of dangers. It is atop an active plate boundary, riddled with volcanoes, perpetually menaced by hurricanes and tempests, and characterized by a built environment that seeks a compromise with the multitude of dangers and, in the manner of compromise, is summarily compromised. As Marie-Sophie Laborieux remarks in Patrick Chamoiseau’s Texaco, “Whoever feared earthquakes, would erect a house of wood. Whoever feared hurricanes or remembered fire, erected a house of stone.”7 A governmental report echoed such a sentiment in 1897, when an earthquake shook Guadeloupe: “Originally built of wood, Point-à-Pitre burned down once. Reconstructed of stone, it crumbled in 1843. Rebuilt of wood, the fire of 1871 destroyed it.”8 In short, it was impossible to build a city to withstand the elements in the West Indies.

Since the earthquake of 1839, which wreaked devastation on Fort-de-France, and that of 1843, which decimated Pointe-à-Pitre, the majority of the islands’ homes had been rebuilt as single-story units made entirely of wood.9 Those that were not made entirely of wood had a stone base with wooden upper stories. Using wood rather than brick or stone allowed load-bearing walls to flex during tremblors, thus preventing the home from collapsing during the region’s prevalent earthquakes. For instance, between 1839 and 1900, there were 1,075 known seismological events in the Caribbean Basin, of which 48 had epicenters in Martinique and 438 in Guadeloupe.10 Lumber construction posed a new hazard, as repeated droughts had dried out the wooden structures, and in incendiary conditions, the homes’ construction allowed fires to easily jump from house to house. Given the threat of earthquakes on the one hand and fire on the other, Caribbean citizens were stuck between a rock and a hard place.

The Caribbean islands were not new to fire. Four-fifths of the principal town of Guadeloupe—Pointe-à-Pitre—had burned down in two back-to-back fires in 1871.11 The city was subsequently rebuilt with more sound building codes, only to burn once more in 1879.12 Fire was simply a matter of life in the Antilles. The use of coal and kerosene lamps to light and heat homes had risen along with the flammable, earthquake-resistant housing, increasing the region’s vulnerability. As historian Bonham Richardson has pointed out, poor members of the black working class could not afford proper glass lanterns or globes, and thus home-made, jury-rigged lanterns became commonplace throughout the Caribbean. Moreover, since the cost of proper kerosene was so high, many filled their improvised lanterns with unstable, highly flammable low-grade oil.13 Urban fires throughout the region increased dramatically as the nineteenth century marched on. While many journalists faulted Fort-de-France’s disaster preparedness and organization, arguing that the prevalence of water and the availability of a sizable firefighting force should have minimized the devastation, the volatile fuel, the ad hoc lighting, the ferocity of the region’s trade winds, and the aftermath of a prolonged drought combined to set the stage for a disastrous fire outbreak.14 The same held true for Port-Louis, where aging wood houses provided ample kindling and an underperforming water pump hampered firefighting efforts.15

Early Sunday morning on 22 June 1890, a resident in a small cabin on rue Blenac in Fort-de-France left a teakettle heating over an open flame, precariously perched over a vase of kerosene used for lighting and heating the home. At around 8 a.m., the stove tipped, the kettle fell, and the floorboards ignited.16 The kerosene exploded, and the small wooden house burst into flames. The Lesser Antilles had been in a massive drought for nearly eight months, and June was in the middle of the windiest time of the year. The fire could not have found more favorable conditions as it jumped from wooden structure to wooden structure, devouring the entire downtown area and chasing people from their homes.17 As dazed firefighters and citizens converged on the scene, they realized that the fire originated in a part of town that had an insufficient water supply with weak pressure, so the pumps could not provide enough water fast enough to slow the pace of the fire. Moreover, since it was Sunday, many of the stores in the commercial district were closed and locked up tight, so access to fire axes was limited.18 Firefighters eventually resorted to demolishing homes in the path of the blaze to create a fire barrier, sundering the air with detonations that sounded to observers like “lugubrious cannon fire.”19 Observers remarked that it was as if the town were “under siege,” which, according to the press, put the citizenry into a panic. As the denizens of Fort-de-France watched their homes and livelihoods go up in flames, they created refugee encampments in the sprawling nearby park known as La Savanne and sought sanctuary in the hills at Fort Tartenson.20

Strong winds from the northwest and the inaccessibility of enough water held firefighters at bay until nightfall, when help arrived from Saint-Pierre and the fire was finally extinguished. In the words of an observer,

[The fire] lasted, it can be said, all day and all night, fostered by a combination of unfortunate circumstances, supported and driven by fate, finding everywhere boons for its destructive work, taking advantage of all: the lack of water, the lack of pumps, the wind which seemed to blow expressly to expand it in all directions, the late arrival of relief, the panic that never fails to occur in such cases and against which only an extraordinary firmness can respond, the absence of authorities, etc., etc. Rarely has one seen a disaster occur in rescue conditions so defective.21

Devastating both the city’s rich commercial center and the poor workers’ district, the fire completely decimated much of the heart of Fort-de-France, burning through major boulevards and small side streets alike.22 Only one house in the path of the fire was saved, and the fire destroyed much of the city’s infrastructure. Though the Palais de Justice and the Direction of the Interior were spared, the fire destroyed the sugar factory at Point-Simon, the hospice, the postal and telegraph offices, the Saint-Louis Cathedral, the customs house, the contributions house, and the Schoelcher Library.23 In short, many of Fort-de-France’s key cultural and administrative buildings had been lost in a matter of hours.

Although Fort-de-France was the administrative capital of the island and France’s military headquarters in the West Indies, it was neither the island’s chief economic port nor its cultural heart. This was not lost on the French press, who, just days after the catastrophe, were quick to point out that the economic hub of Saint-Pierre was doing quite fine.24 Official press releases assured the French population that the sugar plantations and refineries, far from Fort-de-France and its environs, were safe and that Martinique’s faith and credit with foreign and national banks remained sound.25 While the local Caribbean press underscored the scope of the devastation, Parisian papers trivialized the damage to some extent to assuage investors and prevent more capital from being withdrawn from the island. Therefore, while the sugar refinery at Point-Simon in Fort-de-France was indeed important for financial investors and its loss marked a significant blow to Martinique’s already suffering sugar industry, papers hungrily proclaimed that sugar production remained on target at the island’s other refineries, and that investors had little reason to pull their money from their Martiniquais investments.

Contrarily, when the Parisian paper Le Temps reported the subsequent fire in Port-Louis, Guadeloupe, where the fire’s cause was similarly accidental and its progression eerily similar, the paper highlighted the fact that vital sugar factories were in the town’s vicinity and that the fire threatened the local economy.26 The fire’s origin had set some on edge, as it had begun on the night of 28 June in the bedroom of two married servants of a local merchant, Léo Dufau, and from there spread throughout the entire town to destroy its wealthiest quarters.27 With the damage valued at roughly 1.5 million francs, the press highlighted the fact that “the entire commercial and wealthiest part of the town was destroyed.”28 Alarmed that sugar output might dwindle as a result of the fires, some worried that malfeasance by the laboring class had sparked the fire in Port-Louis and perhaps in Fort-de-France as well.29 To allay their fears, Guadeloupe’s private council to the governor put the gendarmerie on high alert and resolved to allocate special funds for merchants’ lost merchandise and industrialists’ equipment not covered by insurance to “help them regain their proper means, their commerce and their industry.”30 Port-Louis’ victimized population of about fifty-eight hundred inhabitants took second billing to economics.

Fig. 4. Popular illustration of downtown Fort-de-France engulfed in flames

L’Univers Illustré, 5 July 1890, cover.

Map 1. Fort-de-France after the fire of 22 June 1890

The destroyed section of the city is darkened to heighten the contrast. Garaud, Trois ans, 231. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

The Commission de Secours in Martinique and the Comité de Secours in Paris

While deprivation, starvation, and confusion followed in the aftermath of the fire, insurance provided no relief. The fire destroyed the financial capital of the Société Mutuelle, a mutual insurance agency that had insured Fort-de-France and garnered capital from its population, and according to press reports, foreign insurance companies agreed to pay only an infinitesimal portion of the total damages, leaving charity the sole recourse of Fort-de-France’s populace.31 In fact, of the 1.8 million francs held in insurance policies, a mere ninety thousand francs, or 5 percent, had been paid out.32 To rebuild Fort-de-France, the French people—Antilleans first among them—really needed to pay for it themselves. Appealing to the hearts and minds of Martinique’s citizens, the press pleaded,

Creole hearts, open yourselves to your unfortunate brethren. Inhabitants of Saint-Pierre and the suburbs, direct to Fort-de-France your devotion, the tireless testimony of your charity. Give to the unfortunate as much as you can. They are ruined but will not die if you feed them. Feed them, in God’s name, in the name of charity, [and] on behalf of compatriotism. In short, bread, rescue, life for compatriots who demand and expect it from you.33

In recognition of Martinique’s help following the 1871 fire in Pointe-à-Pitre, one of the earliest sources of aid to Martinique was its sister island of Guadeloupe.34 Within days Guadeloupe began a public subscription campaign, loaded two cargo ships with food destined for Martinique, and replaced its Bastille Day celebration, this year a costumed gala, with a benefit and raffle for the fire’s victims.35 But a fire devastated Guadeloupe within a week—reflecting the same factors that had enabled the fire in Fort-de-France—and no further help came from this source. In fact, the governor of Guadeloupe opined that this “acknowledgment of debt” had strained its resources now that Port-Louis had gone up in flames.36

Governor Germain Casse created a local relief organization for the establishment of shelter, the distribution of food, and the distribution of clothing the day after the fire in Fort-de-France. On 24 June, Casse established the ten-member Commission de Secours over which Martinique’s bishop, Monseigneur Julien-Francois-Pierre Carméné, presided.37 Such governmental relief commissions had a precedent in earlier disasters, most notably the fires that raged through Pointe-à-Pitre in 1871 and 1879.38 In addition to raising funds from the parishes and municipalities on the island, the commission was charged with documenting, allocating, and distributing all donations received locally and from the metropole.39 Collections began in Martinique’s parishes and townships, raising over one hundred thousand francs (24,415 francs from episcopal and 79,650 francs from municipal donations).40 The governor himself provided a credit of one hundred thousand francs to be distributed among Fort-de-France’s victims, equating to ten francs per victim. Given the price of manioc at the time, this would have paid for nearly two weeks of food.41 A second such credit was opened in August. Within days of the fire, the mayor of Fort-de-France, Osman Duquesnay, created squads of workers to clear the rubble from the city, offering a pay rate of two francs per day supplemented with food rations.42 Support arrived from Saint Thomas, Trinidad, and Demerara, and since Fort-de-France’s most immediate need was food, Jamaica sent three hundred barrels of flour and three hundred bags of rice.43 It was rumored that the U.S. government had planned to donate seven hundred thousand francs, though there is no evidence that this ever came to fruition. In fact, foreign aid to Martinique amounted to only thirty-seven thousand francs.44 Under the urgent conditions, however, the intake and distribution of foodstuffs was not subjected to any form of systematic accounting, which colonial investigators later identified as a “willful ignorance” on the part of both the French military and the municipal government.45

Ultimately, local support was not enough. In a letter from 8 July 1890, just two weeks after the fire swept through Fort-de-France, Governor Casse warned the colonial undersecretary of state that once aid from Martinique’s neighboring cities and islands is exhausted, “the most terrible misery will reign if Parliament and the Metropole do not come to our aide. . . . Without you, we would be lost. . . . We have confidence in France and await full of gratitude.”46 He argued that there was a real danger that public disorder and chaos would ensue if the central government did not intervene. He called on Martinique’s General Council to engender sympathy from the metropole in the name of the victims: “put aside your divisions, your grudges, your hatreds, if you don’t want to paralyze the goal of solidarity that leads the Metropole toward you.” In response, the General Council sent photographs documenting Fort-de-France’s devastation to Paris in an effort to further demonstrate Martinique’s dire need for support.47

However, information was slow in reaching Paris, because the capital’s postal and telegraph offices were lost to the fire. All correspondence had to be rerouted using English telegraph lines through New York via Saint-Pierre, thus drastically slowing communication between the administration in Martinique and the central bureaucracy. Consequently, few realized the full extent of the devastation wrought in Fort-de-France. The entire city west of rue Schoelcher, as well as the section between rue Saint-Louis and rue Saint-Laurent, was destroyed. In fact, journalists lambasted Governor Casse for failing to supply sufficient and timely information regarding the postincendiary conditions of Fort-de-France.48

Relief efforts for Port-Louis were folded into those for Fort-de-France. A month after the two fires, an official centralized relief effort in Paris was led by the “Comité de secours aux Incendiés de Fort-de-France (Martinique) et de Port-Louis (Guadeloupe),” directed by Alexandre Peyron and coordinated by Eugène Étienne. A vice admiral, recipient of the Legion of Honor, former commander of the Antilles naval commission, and former minister of the marine and colonies, Peyron was an irremovable senator—that is, a senator for life—from the center left in the French legislature, while Étienne was an opportunist who received support earlier in his career from ardent republicans like Jules Ferry and Leon Gambetta.49 These two political figures represented the heart of republican empire, and their fund-raising campaign brought people together from across the political spectrum, successfully bridging the gap between assimilationist republicans and socialist deputies. In December 1890, when the Comité had decided to formally disband, Undersecretary Étienne thanked its members for the hard work of dedicated individuals like Admiral Peyron and those he represented. At the behest of Admiral Peyron, Étienne officially commended M. Bertin, the Comité’s accountant and second-in-command, and even formally recognized the work of M. Gerville-Réache, the socialist legislator from Guadeloupe.50

The Comité de Secours carried out a nine-month fund-raising campaign to help the victimized populations of Martinique and Guadeloupe. The Comité sent out two-sided sheets to all the French communes: one side had a description of the disaster written by Admiral Peyron and signed by the committee, and the other side was a form for taking donations. Individuals, business owners, and municipal officials collected signatures and donations, each carrying out their own miniature fund-raising campaign. Oftentimes the activity was conducted at a local event, such as a gala or banquet, or at the local school. The local fund-raisers then turned over the subscriptions to the Comité directly by mailing them to the colonial undersecretary of state or indirectly via the military or local treasurer, who then turned them over to the Comité. Everyone who donated money and signed the subscription paperwork had his or her name published in the Journal officiel de la République française.51

The central government initiated the campaign to raise money, but departmental prefects, mayors, townships, and schools executed it. Thus the fund-raising took a variety of forms. At one point, the prefect of Seine-Inférieure and the president of the local charity committee in Le Havre joined forces to stage a kermesse—a traditional charity celebration in northern France and the Low Countries—designed to raise money for their concitoyens, or fellow citizens, in Martinique and Guadeloupe. The centerpiece of this event was to be a “reconstituted” Martiniquais village built under the direction of a “worker familiar with the assemblage of the pieces [of such displays].” In the organizers’ estimation, this reconstituted village would give “more flair and local charm to this event” and thereby encourage attendees to donate to the cause. The organizers requested materials to build this mock village from the minister of the marine, though they were ultimately denied access to the necessary supplies.52 Nonetheless, several such local fund-raising events took place across France.

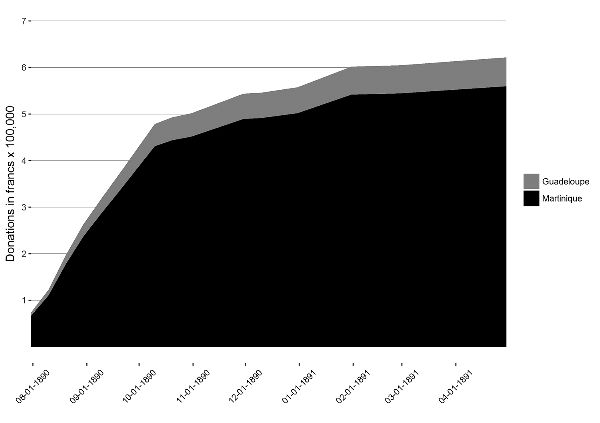

Soliciting donations from the press, prefectures, schools, organizations, and individuals within the metropole—while receiving donations from foreign governments as well—the Comité de Secours raised over six hundred thousand francs within the first few months of its operation (by November), and at that point planned to disband.53 This is a substantial amount of money, given that the average yearly wage for a French worker in the metropole during the 1890s was 1,080 francs, paid at 35 centimes per hour.54 In addition to the Comité’s fund-raising, the central government had already allocated two hundred thousand francs to Martinique on 24 June, and proposed a contribution of an additional three hundred thousand francs to Martinique and one hundred thousand francs to the newly burned Guadeloupe on 8 July.55 Annotated “colonial service” under the financial law of 17 July 1889, this money was earmarked for reconstruction and individual aid in order to stave off what officials feared would be inevitable starvation and disorder.56 The law contributing four hundred thousand francs, about 10 percent of Martinique’s annual budget, to the Antilles passed unanimously—511 votes for and zero against.57 The Comité decided on 25 July 1890 that it would apportion the donations received between Martinique and Guadeloupe. Based on an approximation of the losses within each affected city, the Comité decided to apportion 90 percent of the funds to Fort-de-France, Martinique, leaving 10 percent for the town of Port-Louis, Guadeloupe.58 Though the Comité de Secours had officially dissolved by December 1890, donations continued to trickle in from all over France and its empire until April 1891.

Fig. 5. Comité de Secours donations as distributed to Martinique and Guadeloupe

“Secours aux incendiés de la Martinique et de la Guadeloupe: Liste des souscriptions,” Journal official de la République française, 13 August 1890–30 April 1891, FM 2400COL, carton 92, ANOM.

Between the metropolitan relief campaign and the local fund-raising efforts, 1.7 million francs were deposited into the treasury of Martinique, with roughly half being received by the end of July 1890.59 While some of the funds went to fill budgetary shortcomings, the bulk went toward direct dispensations to the afflicted populace. When the governor opened a credit of one hundred thousand francs on 27 June to be distributed to the population at the rate of 10 francs per victim, the administration divided the city up by roads and appointed a ten-person subcommittee to decide how to distribute the funds. Some of the money was used to create shelters for the neediest families, while the rest was distributed to the populace on 4 July. The fire’s victims presented themselves to the treasury or the revenue office, signing off on the allocated amount of 10 francs. A second credit of 122,320 francs was opened in the same fashion on 21 August, and a third credit of thirty thousand francs provided assistance for previously undiscovered indigents at the rate of 36.80 francs per victim.60 The bulk of the Comité’s funds, however, went toward compensating victims for their structural, property, and commercial losses from the fire at a rate of 10 percent. Distributing 1.3 million francs by the end of 1891, the local Commission de Secours—the organization tasked with distributing the nationally raised funds—paid out a tenth of the declared value of an individual’s losses, which, according to official reports by colonial investigators, privileged small proprietors over the large.61

Due to the overwhelming devastation caused by the 1890 fire, as well as the hurricane that followed on its heels in 1891, it took over a decade to rebuild Fort-de-France. Nevertheless, by 1903, nearly seven-eighths of the city had been rebuilt. The U.S. Bureau of Foreign Commerce described it as a “pretty and interesting town” that was “vastly improved” following the devastation of the 1890 fire. In addition to the funds provided by the Comité, the government of Martinique awarded homeowners 50 percent of the market value of their burned-down homes in order to encourage reconstruction, paying out a total of eight hundred thousand francs to help defray the costs of rebuilding the city’s housing.62 Moreover, Martinique’s General Council provided a credit of three million francs through three-hundred-thousand-franc annuities over a ten-year period to homeowners who lost their homes in the fire.63 By 1 January 1892, the General Council had already used 260,000 francs of those funds to rebuild forty-nine homes, and though the 1891 hurricane had significantly slowed reconstruction and posed a host of new problems, colonial investigators acknowledged that the reconstruction of Fort-de-France was proceeding “at great steps.”64 Following the 1890 fire, officials acknowledged the riskiness of the Caribbean’s built environment. In their reconstruction efforts, officials mitigated the dangers of earthquakes on the one hand and fires on the other by establishing new regulations that required new wooden homes to be built with a metal framework. Similarly, the town of Port Louis in Guadeloupe revised its construction standards to make homes more resistant to fire.65

Laicization: Religious Fund-raising in Martinique, Lay in the Metropole

Catholicism played an important part in the relief effort, as Martinique had been integrated into the French Catholic Church during the Second Republic, becoming part of a diocese that included Guadeloupe and Réunion. This diocese was attached to Bordeaux, largely due to the close commercial relationship with the city that began during plantation slavery. In a world often characterized by metropolitan Frenchmen as ancien régime, Catholicism played a large role in the everyday life of the denizens of the French Antilles. According to one American priest, “Martinique forms a striking contrast with some parts of France. The Lord’s day is well kept, the churches crowded at every religious function and the sacraments are observed frequently.”66 Unlike the new colonies, where French administrators felt strongly that “anticlericalism was not for export,” however, Martinique was not free from the French state’s push for laicization and the culture wars that came to characterize the Third Republic.67 The government nominated its bishop, and the Church approved the nomination. The 1880 laws that secularized instruction in the metropole were also extended to the old colonies, and secular instructors replaced the Frères de Ploëmel, the religious order from Brittany tasked with restructuring the school system in Martinique and Guadeloupe after emancipation in 1848.68

The management of donations reflects this division between religious adherence and mounting republican secularism. The Catholic Church oversaw the local Commission de Secours, while the metropolitan Comité de Secours was purely a secular organization. The sources of the donations also reflect this division: religious organizations accounted for a very small percentage of total donations collected by the metropolitan Comité de Secours, whereas much of the Commission’s fund-raising took place in parish churches. That is, while virtually all local donations were filtered through the church in Martinique, religious donations raised by the Comité de Secours in the metropole accounted for only 0.26 percent of all money raised for Martinique and Port-Louis. By contrast, municipal and communal collections in the metropole accounted for nearly 20 percent; banquets for 11 percent; educational institutions for 10 percent; and commercial institutions for roughly 6 percent. While donations originating from metropolitan religious institutions were likely filtered through the municipal, communal, and public collections, it is nevertheless significant that they were not counted as distinct and were instead folded into the secular metropolitan bureaucracy.

The distinction between a Catholic colony and a secular metropole engendered disputes over what the state was obligated to repair. In 1892, when colonial investigators reopened an examination of the distribution of funds and supplies for the victims of the 1890 fires, they were insistent that the state not pay for the reconstruction of religious buildings on the islands following the 1891 hurricane. The investigatory commission believed that “the state is not fairly obligated to contribute with the communes to such costly expenses for the exercise of religion,” but instead should only fund the reconstruction of buildings that serve a “necessary and incontestable public utility.”69

Although “secularism was not for export” to the colonies at the end of the nineteenth century, the struggle between secularism and Catholicism came to characterize local understandings of the fires in Fort-de-France and Port-Louis and their significance. The disagreement over whether the French Antilles were a secular or religious space was encoded in the way in which the local press covered the disaster, split between conservatives who saw the fire as an act of God that societal charity and individual faith could rectify, and republicans who viewed the entire catastrophe as the machinations of local politics and governmental malfeasance. The ashes of Fort-de-France, the administrative hub of the island, were a backdrop to divergent political views—conservatives evinced a strong allegiance to an old-fashioned understanding of Martinique as a relic of a Catholic ancien régime France, while republicans framed the disaster in the context of an ongoing political war between leftists under Deproge and centrists under Hurard. Calls to aid from the population were framed in very nationalistic language: those who donated were true patriots, while those who did not contribute were “anti-patriots” who did not hold true to their republican values.

Nearly an Algeria: The Cultural Significance of Antillean Citizenship and Disaster Relief

Public relief was intricately tied to the legal and cultural incorporation of the French Antilles into the Republic, as well as the extent to which Antilleans were seen as equals to their metropolitan counterparts. Germain Casse’s position at the head of the local relief effort ensured the connection. As the appointed governor of Martinique from 1889 to 1890 and a longtime advocate of equality for French Antilleans, Casse was a creole born of an emigrant Frenchman and a local woman in Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe. As a mixed-race man who spent much of his early life in Paris, where he attended grade school and later earned his law degree, he was an outspoken supporter of full assimilation of the French Antilles, and writers like Armand Corre described him as “at the helm” of the mulatto politicians.70 Under the Second Empire, Casse fought for the establishment of a republic, and during the siege of Paris commanded the 135th battalion of francs-tireurs, or irregular troops who used guerilla tactics against the Prussian army. As a Blanquist socialist who expressed his sympathy for the French Commune and later attended the First International Workingmen’s Association, Casse sat on the extreme left of the French National Assembly during the early years of the Third Republic, first as the deputy from Guadeloupe and then as the deputy of the Seine.71 As a radical, he fought to abolish the presidency and secularize the republic, though he became tempered in his radicalism in his later years and sought a rapprochement with parliamentary moderates and opportunist republicans. As a mulatto from Guadeloupe at the center of Parisian politics, he embodied the republican ideals of colonial assimilation, as well as the Third Republic’s penchant for parliamentary dilettantes. As the following caricature by André Gill from the irreverent Les Hommes d’aujourdhui demonstrates, Casse’s contemporaries saw him as a champion for combining the Antilles’ African heritage with French culture during his time in office. Les Hommes d’aujourd’hui described him as follows: “His revolutionary temperament, his spirit of independence, his love of liberty, his conscience which clerical education could not diminish, his just sentiments led him to seek emancipation in the Republic and freedom of thought.”72 However, due to his political leanings and, probably, his mixed heritage, many in the financial world did not like him, viewing his focus on Antillean citizenship rights as an impediment to their interests in the Antilles. The Gazette agricole unfavorably described Casse as a “journalist without talent” whose governance in Martinique had demonstrated “incapability without equal,” and others criticized him for his political “zigs” and “zags.”73 In 1886 he was even the target of an unsuccessful assassination attempt by Jean Baffier, a deranged nationalist sculptor who followed the infamous anti-Semite Edouard Drumont and saw Casse as an impediment to the reawakening of Gaul.

The cultural importance of the relief campaign, and its connection to Antilleans’ citizenship rights, was not lost on the Comité’s membership, who were interested in bringing relief to the Antilles precisely because they were French and republican. In fact, the “honorary president” of the Comité was Victor Schoelcher, the French statesman who championed slave emancipation and black citizenship in the Caribbean.74 Making his call to the French population’s generosity in the Comité’s official press announcement, Admiral Peyron expressed his certitude that everyone would give generously, “for, it is never in vain that one calls upon the sentiments of solidarity that unite all members of the French family.”75

The Comité successfully appealed to Frenchmen’s shared citizenship with their compatriots in Martinique and Guadeloupe. The Parisian newspaper Les Tablettes Coloniales exclaimed that “the call for help addressed to us by our Antillean compatriots . . . will be heard, this cry will not stay without echo. All that is possible to do to help the numerous unfortunate people, France will do without hesitation, bringing to [the task] full alacrity and heart.”76 The newspaper went on to assert that “this is not only a humanitarian question, but a patriotic duty that everyone in France will be able to understand. . . . It is incumbent upon all of France, and by that we mean not only the metropole, but also all its colonies, to come to the aid of this dignified population.”77 Likewise, imploring fellow citizens to remember “the links which unite you with our colony of Martinique,” Bordeaux opened its own subscription campaign and called upon its citizens to help “your unfortunate compatriots without respite or food,” for the people of Martinique “wait for the mère-patrie to lift them from the ruins and assuage the miseries accumulated by this terrible catastrophe.”78

This familial language certainly conveys the sort of paternalism many historians of French colonialism have highlighted. Martinique was indeed still a colony, though one with a special place in French culture, and as such it was still subject to the eugenic and paternalistic mindset prevalent in turn-of-the-century France. Martinique was described as a tropical version of ancien régime France, and most descriptions of the fire were rife with discussions of coconut palms, brightly colored headdresses full of bananas and other tropical fruits, and traditional dances with untraditionally mixed-race peoples.79 Few articles in Parisian papers, particularly those dealing directly with colonial issues like Les Tablettes Coloniales, neglected to append racial typologies to the end of their articles on the Fort-de-France fire: images of the prototypical creole woman, the mulâtress, or the Negress stood side by side with images of the island’s devastated capital city.80

Fig. 6. Caricature of Germain Casse holding a white French child and an African child

Illustration by André Gill, Les Hommes d’aujourd’hui 3, no. 133 (1881), Paris.

Nevertheless, several metropolitan cities like Bordeaux underscored their linkages to the island—which, granted, had been forged through chattel slavery and the exploitation of forced sugar cultivation—and the duties incumbent upon citizens to help one another. While ultimately Bordeaux was not among Martinique’s primary benefactors, the origin of the donations received by the Comité demonstrated the more general linkages between the metropole and Martinique. Most of the donations received over the course of the Comité’s nine-month campaign came from public and communal collections, banquets, and educational fund-raising (figure 7)—in short, from everyday Frenchmen, women, and children.

While the majority of funds came from Paris itself, home to the financial institutions and the largest population in France, the spread of donations across France reveals the breadth of the fund-raising campaign (map 2). In part, this widespread participation likely reflects the minister of the interior proclaiming an official subscription in the school system, as well as a testament to the interconnectedness of France by the close of the nineteenth century. The bulk of donations came from public collections, which shows that knowledge of the disaster, as well as an interest in the well-being of the victims, extended across the metropole. According to L’Illustration, the news of the fire “caused a commotion in France, because, more than any of our other colonies, Martinique is in constant contact, familial relations most of all, with the mère-patrie. There are few Martiniquais, few families of settlers established there, who don’t have very close relatives here. It’s nearly an Algeria, if not by extent or proximity, at least by links of the heart.”81 The Journal des Voyages echoed this very sentiment for its readership in France, supporting their involvement in the fund-raising campaign.82

The regions of France that were the most ideologically invested in the well-being of their concitoyens in the Caribbean were also the least invested financially—discounting Paris, through which all money in France ultimately flowed. The largest donations came not from the mercantile powerhouses of Marseille, Bordeaux, Le Havre, and Nantes that had close economic ties to the Antilles dating to the islands’ slave past, but from the fringes of the French nation that had little to no financial connection to Martinique and Guadeloupe (see maps 2 and 3, figure 7). Of the total tonnage of goods arriving in the metropole from Martinique in 1892, 26 percent went to Marseille, 34 percent to Bordeaux, and the remaining 40 percent was split between Le Havre and Nantes. In fact, nearly a third of sugar from Martinique, and a quarter of all commerce, went through Marseille alone.83 While they accounted for roughly two-thirds of all trade with the French Antilles, Marseille and Bordeaux combined donated a total of 0.5 percent of all money raised for Martinique and Guadeloupe, with Marseille itself falling just behind the far distant Pondicherry, a French colony in India until 1954. In fact, the Gironde department (Bordeaux) was ranked among the lowest donors per capita, while Loire-Atlantique (Nantes) and Bouches-du-Rhone (Marseille) were in the class of second-to-lowest donors. One exception to this rule was Le Havre, which held a special charity event for which they requested materials to “reconstitute” a model Martiniquais village. Seine-Maritime/Seine-Inférieure (Le Havre) ranked among the tier second from the top.

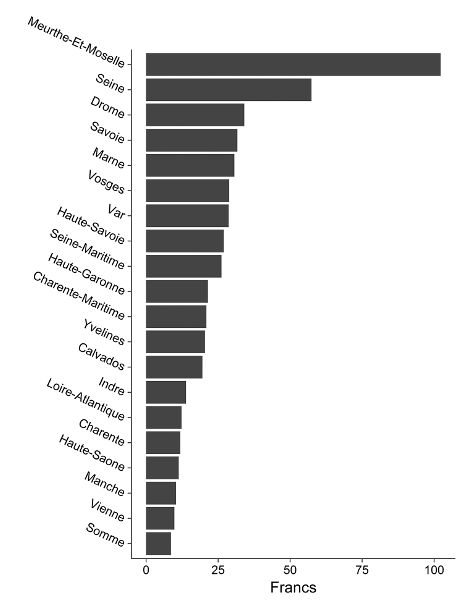

The region of Lorraine, specifically the department of Meurthe-et-Moselle, had by far the largest donations per capita, at ten centimes per inhabitant (maps 3 and 4; figure 8; tables 2 and 3—101.25 francs per thousand; median, 22.5; average, 83.3). This department represented the remnants of what Germany had seized in the Franco-Prussian War from the former departments of Moselle and Meurthe. Its rate of donation exceeded that of the far wealthier and business-oriented department of the Seine, which included the financial powerhouse of Paris. Perhaps this generosity reflected the region’s own revanchisme, or its need to prove Lorraine’s Frenchness after the disaster of the Franco-Prussian War, but the disaster in Martinique clearly resonated in Lorraine, which was rural yet industrializing. Lorraine was France’s primary iron-ore mining region, and figures from 1896 put Meurthe-et-Moselle as, by far, France’s leading provider of cast iron.84 The department mined and smelted over 1.4 million tons (62 percent of France’s total output)—1.2 million more tons than the next highest producing department in France, Le Nord.85 Though fairly well-off, with a well-balanced economy split between agriculture and industry, Meurthe-et-Moselle was far from fabulously wealthy, lagging behind the Seine with regard to the percentage of rentiers comprising the department’s population. Only 3.61 percent of the department’s population could sustain itself from income earned from investments, while 5.54 percent in the Seine and 6.71 percent in Seine-et-Oise could. In this Meurthe-et-Moselle fell in the seventy-fifth percentile among French departments, which suggests that its donations did not impose hardship as it might among citizens of departments like Le Nord (1.19 percent, tenth percentile).86

Fig. 7. Donations by origin and sector, Lorraine versus France, 1890–91

Overall donations (left) versus donations in Lorraine (right) received by the Comité des Secours, broken down by sector. Graph created in R statistical package with compiled donation data from FM 2400COL, carton 92, ANOM.

Nonetheless, the coverage of donations from Lorraine is astonishing (see map 2). While public collections and relief banquets held in Nancy generated the bulk of donations, nearly every commune in the region donated to some degree. The nationalist campaign in Lorraine likely drove this coverage; the “civilizing mission” had sent a legion of cultural ambassadors through the school system to heighten awareness of Lorrainers’ French nationality. The French government used the public school system in Lorraine to acculturate what it saw as a backward and fairly autonomist peasantry to the mores of the French urban centers, heightening this attempt following the loss of Alsace-Lorraine to Germany during the Franco-Prussian War. As historian Stephen Harp has shown, the French government believed that Lorrainers had to “learn to be loyal” to the French nation, and with the goal of nation building from 1850 to 1871, the government sent a veritable army of French schoolteachers to the region to teach French history, culture, and language.87

Map 2. Donations within France, 1890–91

Geo-located donations plotted within France with Gephi. All nodes are the same size and represent a donating commune. Donation data from FM 2400COL, carton 92, ANOM.

Map 3. Donations in francs per thousand by region of France, 1890–91

Note the high number of donations in Lorraine. Map created in ArcGIS with five natural breaks (Jenks). Population statistics from Social, Demographic, and Educational Data for France, 1801–1897, ICPSR00048-vol. 1. Donation data from FM 2400COL, carton 92, ANOM.

Map 4. Donations in francs per thousand by department of France, 1890–91

Note the high number of donations in the department of Meurthe-et-Moselle, in the Lorraine region. Map created in ArcGIS with five natural breaks (Jenks). Population statistics from Social, Demographic, and Educational Data for France, 1801–1897, ICPSR00048-v1. Donation data from FM 2400COL, carton 92, ANOM.

The widespread support for the French Antilles was connected to the growth of the republican public education system. Schools made up one of the primary donors to Fort-de-France and Port-Louis, because the minister of public instruction authorized collections in all public schools in France.88 Yet even more important was the schools’ role in acculturating the populace and encouraging them to donate. e education system’s role as a vehicle for republican values was strongly felt in Lorraine as in Martinique, where middle-class mula os were both the island’s leading republicans and the primary bene ciaries of a public education system modeled more closely on that of rural regions like Lorraine than on the colonial education system found elsewhere in the French empire.

Fig. 8. Top twenty donating departments, 1890–91

Francs per one thousand people. Graph created in R statistical package with compiled donation data from FM 2400COL, carton 92, ANOM.

Table 2. Top twelve donating departments and amounts donated, 1890

| Department | Francs |

|---|---|

|

Ville de Paris |

167,849 |

|

Meurthe-et-Moselle |

45,507 |

|

Seine-Maritime |

21,857 |

|

Nord |

13,747 |

|

Marne |

13,398 |

|

Yvelines |

12,840 |

|

Vosges |

11,803 |

|

Drôme |

10,391 |

|

Haute-Garonne |

9,966 |

|

Charente-Maritime |

9,527 |

|

Calvados |

8,395 |

|

Savoie |

8,292 |

Note: Meurthe-et-Moselle had the second-highest contributions.

Source: FM 2400COL, carton 92, ANOM.

Lorrainers’ donations reflected a strong impetus to prove their republican convictions. As historian Mark Sawchuk has shown with respect to Nice and Savoy, those regions within France that had to prove their Frenchness were the most invested in French republicanism. After hearing the final sum donated by Meurthe-et-Moselle, colonial undersecretary Étienne wrote to the prefect at Nancy, “I would congratulate you especially for the remarkable results that you have achieved in this charitable work, and to heartily thank you for the momentum you’ve given to this movement of sympathetic commiseration that has manifested itself in Meurthe-et-Moselle in favor of our unfortunate compatriots of the Antilles.”89 The resonance of this disaster in Lorraine demonstrates the extent to which Lorrainers internalized republican ideals, most notably those of cultural and political assimilation.

Table 3. Top twelve donating departments and donations per thousand, 1890

| Department | Francs |

|---|---|

|

Meurthe-et-Moselle |

102.25 |

|

Seine |

57.42 |

|

Drôme |

34.11 |

|

Savoie |

31.71 |

|

Marne |

30.64 |

|

Vosges |

28.84 |

|

Var |

28.67 |

|

Haute-Savoie |

26.97 |

|

Seine-Maritime |

26.18 |

|

Haute-Garonne |

21.46 |

|

Charente-Maritime |

20.93 |

|

Yvelines |

20.42 |

Note: The donations from Savoie and Haute-Savoie reveal their strong commitment to French republicanism and strong distrust of monarchism and Bonapartism based at least in part on their recent incorporation into the French nation, in 1860, and their deep Italian republican heritage.

Source: FM 2400COL, carton 92, ANOM.

Aside from Paris, in which all economic, financial, and bureaucratic functions were centralized, the largest donations came from those regions with the weakest financial ties to the Antilles, as well as the weakest connection to the traditional conceptualization of France. Those departments that donated the most were precisely those that had to prove their French national identity.

Embers in the Ashes: Looters, Brigands, and Smoldering Political Differences

The day after the fire in Fort-de-France, a disgruntled man was arrested in Saint-Pierre near several barrels of oil outside a storefront, shouting, “Down with the 18th of July! Long live the fire!” Though the press labeled him a crackpot, monomaniac, or hoaxer, it admitted that there was a palpable—and in their view, justified—fear that the Fort-de-France fire would not be an isolated incident, for “every misfortune that erupts soon finds its counterpart somewhere else.”90 The press and authorities anticipated that someone might rekindle the fire in Fort-de-France—or perhaps even spread it to Saint-Pierre—or that panic would throw the entire population into violent pandemonium. In light of fears of disorder and widespread panic, therefore, gendarmes patrolled Fort-de-France to prevent looting, particularly of the storehouses of food at the unburned military base at Fort Louis. In fact, a destitute group of fire victims—whom the press labeled an outside influence—attempted to procure supplies from that military storehouse, where gendarmes intervened with bayonets.91

The city was placed under siege, and as the press put it, “Military surveillance is ceaselessly very active and severe in Fort-de-France. It’s necessary. Bands of looters, rogues, vagabonds—those birds of prey that one meets after any tempest, feasting among the debris, those foxes and jackals who live on spoils—are beginning to infect Fort-de-France, certainly looking to, it is said, revive the fire.”92 In the wake of any natural disaster, the fear of looters and brigands typically emerges—a fear thoroughly laced with racism and classism stemming from political tensions that predate the disaster. Recent sociological studies have shown that social identification, racial prejudice, historical memory, and media attention heavily influence how survivors, governments, first responders, and the public make sense of disasters.93 The threat of looting and panic following a natural disaster is rarely a reasonable concern, and when looting does occur in a disaster—or perhaps, to be more accurate, is perceived by authorities—it is often intimately tied to political stresses.94 In a world turned upside down one person’s “survivalist” is another’s “looter,” and the distinction nearly always reflects race, class, or politics.95 Synthesizing sociological findings across numerous disasters in the United States and several abroad, Thomas Drabek has found that “[w]hen victimized by a disaster—be it a flood, tornado, or earthquake—most individuals evidence behavioral continuity and remarkable composure.”96 Rather than falling into pandemonium as contemporary news reports cautioned—as they have recently in the wake of Hurricane Katrina (2005), the Haitian earthquake (2010), and the Japanese tsunami and nuclear meltdown (2011)—disaster survivors typically evidence “constructive, goal-directed behavior” and acts of selflessness and community.97 While panic is possible, it is not common enough to merit the attention the media gives it, and it represents the extreme end of the spectrum of human responses to disaster situations.98 Even today, however, the mass media and official discourse continue to promulgate ideas proven to be false by years of empirical research, and these “disaster myths”—most notably the panic myth—have real consequences for how disaster survivors behave and how official authorities respond.99

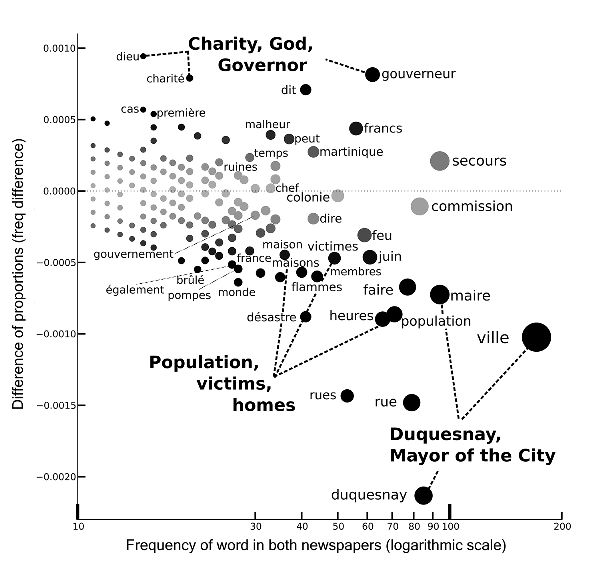

To temper, or perhaps to mask, the grievousness—or rather, the baselessness—of “blaming the victim,” the French press tried to paint the “pillagers” as an outside influence disrupting the otherwise tranquil Fort-de-France population.100 Martinique’s republican newspaper, Les Colonies, vociferously opposed this assertion, claiming it was an unfair attempt to off-load responsibility onto the rest of the island.101 Instead, it pinned responsibility on the elected mayor of Fort-de-France, Osman Duquesnay, because he was the leading political opponent of the newspaper’s editor, Marius Hurard. The newspaper summed it up as follows: “A city burned with 35 million lost and 5,000 people without respite . . . is certainly a beautiful trophy in the arms of M. Duquesnay. . . . Can we at least hope that this will be the last, and that our population, so cruelly struck, will finally open its eyes to the acts of this scoundrel and understand his immorality.”102 The great fire, as well as the public’s perceived incompetence of Duquesnay’s response, fed into the ever-growing rift in Martinique’s Republican Party after 1885. At the time of the fire, wealthy middle-class mulattos dominated Les Colonies, and their largest political opponents came from the far left: the socialist republicans led by Ernest Deproge who had split from the Republican Party five years earlier. Though Les Colonies framed the disaster in terms of its human costs, its calls for charity revolved around political patriotism and were predicated on party allegiance.

Tensions flared between Mayor Duquesnay and Governor Germain Casse, who shared no love for one another. Casse threatened to imprison Duquesnay at Fort Desaix if any further misfortune, fire or otherwise, befell Fort-de-France.103 Undoubtedly a hollow threat, it nevertheless illustrated the level of discord between the municipal and colonial governments—one that continued through the relief effort to follow. In a broadside posted throughout the city, Duquesnay’s political opponents accused him of incompetence and political maneuvering in the face of real disaster.104 Duquesnay argued that Casse had overstepped his legal authority in creating the local Commission de Secours, and he was disgruntled that his name came below that of the mayor of Saint-Pierre in the commission’s roster. For center-right republicans, the true culprit was not Casse but Duquensay himself and the political infighting he incited in Fort-de-France by being a political opportunist.105 In fact Les Colonies ran for several months and in very large letters a quote from Victor Schoelcher, who in 1884 lambasted Duquesnay for his political opportunism. The quote painted Duquesnay as an unworthy politician whose place in Martiniquais politics was not only a great shame but also shameful.106

While Les Colonies considered the entire catastrophe a result of Duquesnay’s blunderings, the conservative Catholic newspaper Les Antilles treated the fire as an act of God that the charity and faith of the good parishioners of Martinique should alleviate (figure 9). The conservative paper was geared toward the island’s white plantocracy, and as such it held a strong association with an ancien régime France characterized by centralized government. Therefore, it focused much more heavily on the metropolitan government’s response, as well as the role played by the appointed governor. It underscored the inequities prevalent among the people of Fort-de-France, even discussing the event as an opportunity for Fort-de-France to mend its ways and stop the persistent political infighting that had come to characterize the island’s locally elected assembly.

A telegram from Saint-Pierre to Paris was quick to put the fire in the context of the political battles and social tensions of the late 1880s, casting the fire as further proof that Martinique—“with its discord, hatreds, and excessive ardors”—is like “an overheated machine threatening to erupt.”107 Some Catholics saw the fire as a form of divine retribution, for “God has his designs . . . and Fort-de-France had wrongs to right,” and they considered the fire a means of setting the wayward Fort-de-France on the proper path.108 The biggest wrong in their eyes was impiety and the declining importance of Catholicism—something which, by the 1890s, was felt all across France—but religious conservatives also saw Fort-de-France as filled with excessive emotions engendered by political discord—namely due to the 1885 split in Martinique’s Republican Party between Marius Hurard’s Progressives and Ernest Deproge’s Radical Socialists—and the economic downturn.109 Labor unrest in Martinique continued to rise in the 1890s due to the volatile world sugar market, eventually culminating in the Antilles’ first general strike in February 1900, covered in chapter 4. The press coverage betrayed a primary concern for the financial solvency of the city, especially losses to the businesses, docks, and sugar refinery at Point-Simon.

Fig. 9. Difference of proportions in newspaper vocabulary, 1890

Frequently used words appear larger and farther along the x-axis. Words associated with Les Antilles (top), the conservative religious journal, appear higher and are colored darker, whereas words associated with Les Colonies (bottom), the centrist republican journal, appear lower and darker. Words shared by the two newspapers appear in the center in light gray. We can see that “governor,” “god,” and “charity” are more closely associated with Les Antilles, while “population,” “victims,” “homes,” “city,” and “duquesnay” are more closely associated with Les Colonies.

French officials took upon themselves the responsibility of protection and relief, reflecting their own societal and political visions in the reconstruction effort. As journalist Naomi Klein demonstrated in The Shock Doctrine, the growth of liberal, free-market economics fit hand in glove with what she terms “disaster capitalism”—or the use of cataclysmic moments to reshape the economic and political world of those affected.110 In the view of Martinique’s conservatives and their counterparts in Paris, the denizens of Fort-de-France needed to align themselves with “calm, order, and tranquility” in recovering from the disaster and rebuilding the city. The first wave of donations came from financial and commercial powerhouses in Paris, many of whom had financial investments in Fort-de-France.111 Perversely hoping that the fire had “consumed the discord, hatred, and excessive enthusiasm that boiled over there [in Fort-de-France] as if in a furnace,” conservatives in Saint-Pierre argued that while atrocious, the burning of Fort-de-France presented an opportunity for rebirth:

We’ll see if, with a change in material situation, it’ll bring about change in ideas and feelings. . . . City of Fort-de-France, sister city of ours, we take part in your grief; we share, as brothers, your affliction, and we wish to lift you up from your ruins. We will help you even. But lift yourselves up in wisdom. Lift yourselves up with sane ideas, lift yourselves up in right sentiments, lift yourselves up with noble resolutions, lift yourselves up with a greater faith, lift yourselves up with all the elements of a true and solid prosperity.112

By mid-August, conservatives in Paris began a racially charged diatribe against the victims in Martinique, asserting that the fire in Fort-de-France was the machination of a corrupt elected official who wanted to win over a disgruntled black population. A sensationalist article in La Paix asserted that the fire was an act of political vengeance wherein “a man occupying an elected position set fire to the city with the certainty of being approved by the black population. Negros repeatedly blocked the efforts of the fire fighters, and Negresses propagated the fire.” The article continued that “this explosion of animosity toward France manifested itself in the same conditions in Port-Louis [Guadeloupe] where the fire was equally set by a criminal hand.”113 Les Antilles lambasted the article as inaccurate, ridiculous, and absurd, framing its sensationalism as evidence of Martinique’s strained relationship with France.

The knowledge that the governor of Martinique, Germain Casse, was himself a person of color did little to assuage the alarmed Parisian press. The Journal des fonctionnaires accused Governor Casse of malfeasance, arguing that he delayed in responding to the fire, showed insensitivity by strolling through the still-burning streets with a lit cigar hanging from his mouth, and diverted relief funds from the victims to his political allies. Such negativity toward officials was commonplace at the close of the century, becoming a hallmark of parliamentary politics under the Third Republic. Alleging a track record of “the illegal suppression of the local government, the impoverishment of the colony, . . . [and] his heinous and passionate politics that have furthered divisions,” the Journal implored the colonial undersecretary of state to remove Casse lest he siphon off the remaining funds destined to rebuild the city.114 Casse was reassigned as the treasurer of Guadeloupe on 24 August 1890 and replaced by his own minister of the interior, Delphino Moracchini, who had been instrumental in distributing fire relief supplies.115 Prompted by Duquesnay and the newly appointed governor, the local government conducted an investigation into the appropriation of the relief funds to see if money had been embezzled. The investigatory commission found no malfeasance, identifying only a few negligible irregularities in the distribution of foodstuffs and supplies to the fire victims.116

The French press and authorities underscored the threat of looting in disaster situations, deploying the military for the dual purpose of providing relief and ensuring security and public safety throughout the Third Republic. The béké-dominated conservative press on the island was overwhelmingly fearful of mass panic and looting, and though they were quick to emphasize that the victims were not the perpetrators—that outside elements were exploiting the poor and the indigent—they nevertheless underscored the perpetual threat of criminal activity. This desire to safeguard public tranquility against the threat of civil unrest—whether real or imagined following natural disasters—had very real consequences for the population of Martinique. It was this strong desire to keep order during the days before the eruption of Mount Pelée, for instance, that kept so many within harm’s way.

At the same time, the French press also underscored similarity between the victims of the Antillean fires and metropolitan republicans. On the one hand, the citizens of Martinique and Guadeloupe were concitoyens in need, while on the other hand they represented the most radical elements of the French left—“pétroleuses” (the politically motivated female arsonists who had come to characterize the Paris Commune), socialists, and malcontents—as well as the worst that parliamentary government had to offer—electoral fraud, administrative corruption, and embezzlement. The right’s unfounded concerns over looting and the general unruliness of the unwashed masses in Martinique and Guadeloupe echoed those leveled by the French right within the metropole against their political opponents in the French legislature.

In any case, the parallels drawn with Algeria, which held a similarly impactful and problematic place in France’s understanding of itself, as well as the depth and breadth of donations received from everyday Frenchmen, suggest we must take seriously the Comité’s appeal to the French citizenry on the grounds of compatriotism and the duty to help beleaguered concitoyens of the Antilles. The reaction in the French press to a disaster within the metropole itself employed the same kind of paternalistic, racist dialogue that underlay public discussions of the great Antillean fires. Comparing depictions of “colonial citizens” to what I call “metropolitan colonials” reveals that the dynamics and paradoxes found in colonial citizenship also apply to denizens of the mainland itself. Late nineteenth-century colonialism cannot be understood strictly in the straightforward geographic terms of “here” and “there.”

From Colonial Citizens to Metropolitan Colonials: The Saint-Étienne Mine Collapse

Coal mining is a notoriously dangerous enterprise, and the dramatically increasing demand for coal in the late nineteenth century compounded the danger as coal miners felt the pressure to maximize production at the expense of safety. Like the constant threat of hurricanes, fires, and earthquakes on the faraway islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe, the persistent risk of mine accidents—explosions, floods, and collapses—haunted the small town of Saint-Étienne in the heart of France. This town along the River Furens in the department of the Loire had a long history of mining disasters. The town was constructed above coal deposits, and the numerous nearby coal mines had undermined it with passages, so the threat extended beyond the miners themselves to their family and friends in the village above.117 Moreover, Saint-Étienne’s officials resembled Martinique’s and Guadeloupe’s in their concern for economics over human safety; just substitute coal for sugar.

Near midday on 3 July 1889, over two hundred miners were buried alive at a coal mine in Saint-Étienne when a gas pocket known as a firedamp exploded. Within minutes, four thousand of the town’s nearly 111,000 inhabitants had rushed to the nearby mine, along with the police and the mine company’s personnel, but given the gruesomeness of the explosion, the main task in the aftermath was not to rescue survivors but to excavate bodies from under four hundred meters of earth.118 For those not killed in the immediate blast, asphyxiation quickly set in, and only a very small portion of the victims was ultimately saved. At least 162 cadavers of the trapped miners were recovered, and of the 213 miners who were trapped within the mine that day, only six survived.119 The disaster presented a mortal danger to the rescue crews as well. Of the forty-nine rescuers who had been working in the nearby Saint-Louis pit, only two survived. In fact, four rescue workers passed out on entering the mine—three were revived in open air, one fell to his death—and one rescuer suffocated in a pit that was eighteen hundred meters from the explosion’s point of origin.

The 1889 disaster was the largest mining catastrophe in France until the Courrières accident of 1906, and the danger persisted long after the initial explosion. Fires continued to rage in the damaged mines, and the gas pocket remained to menace the workers. For instance, two days after the disaster, at least sixty miners at the Rimbaud pit rapidly evacuated upon noticing an irregularly large flame in their safety lamp.120 It took until August 1890 to drain the Saint Louis mine pit after the explosion in July 1889.121 But before the wreckage of the previous catastrophe had been cleared, disaster struck again on the night of 29 July 1890, when over 150 miners working for the Villeboeuf company fell victim to poor ventilation in the Pélissier pits.122 An explosion ripped through the night air when volatile gases collected once again into a firedamp.123 Enveloping miners in what one reporter called “a hurricane of gas,” this tragedy, which killed about 120 miners and wounded roughly thirty-five, represented the town’s fifth major mining accident in thirty years: an explosion in the Jabin pits killed seventy-two miners on 9 October 1871 and then another two hundred one month later on 8 November 1871.124 Another explosion in the Jabin pit in 1875 killed approximately 226 people, with only one hundred bodies of the deceased recovered for burial.125 A collapse at Chatelus killed ninety miners on 1 March 1887, and the disaster at the Verpilleux pits in 1889 had killed over two hundred.126

The place of the miners at Saint-Étienne in French society was in many ways analogous to the place of the Antillean fire victims. Aside from being in a perpetual state of disaster, sitting under Damocles’ sword, as it were, they were also at the bottom of the social ladder within France, and, as Eugen Weber has shown, had only been recently integrated into the Parisian-dominated French nation-state. As the image from L’Illustration shows (figure 10), race and class were inextricably intertwined in the French imaginary. Not only were the workers dispossessed of rights, property, and safe living and working conditions, as were their compatriots in the Antilles, they were racialized in a similar fashion. The authors of L’Illustration explained that the workers’ lips were swollen and their bodies charred from the fire, and that their artist’s engraving tried to replicate the, in the author’s words, “blackened” nature of the corpses.127 Though undoubtedly the miners would have been horrifically disfigured and burned, the artist’s rendition of the cadavers replicates far more than mere disfigurement. Nineteenth-century viewers would have readily seen in the image the racial typologies prevalent in France at the time, for the miners had been “blackened” in more ways than one. In fact, the trope of washing the blackness away from the African saturated soap advertisements at the start of the twentieth century in the francophone world.128 Running alongside this trope in some advertisements, such as that for Le Savon Dirtoff printed here, was the notion that one’s labor blackened his skin. In such cases, only the soap and cleaning products afforded by modernity and progress could bring the laborer from savagery back to civilization.

Fig. 10. Rescuers discovering victims at Saint-Étienne, 1889

An image of the mining disaster’s victims racialized as black colonials, with a rescuer entering from the right. The miners have blackened skin, pronounced lips, and short, curly hair—all characteristics of contemporary black stereotypes. “La Catastrophe de Saint-Étienne,” L’Illustration: Journal universel, 13 July 1889.

Fig. 11. Rescuers discovering victims in the Verpilleux pits, 1889

An alternative image of the mining disaster’s victims, with rescuers entering from the right. “L’Explosion de Grisou au Puits Verpilleux, à Saint-Etienne,” Le Petit Parisien, 14 July 1889. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Fig. 12. Miners at work in Saint-Étienne, 1890

In this postcard (circa 1890), what was omitted from the artist’s rendition found in L’Illustration (see figure 10) is plain to see—pants, shirts, boots, and helmets. Courtesy of the author.

Fig. 13. acist soap advertisement for Le Savon Dirtoff, circa 1930

This poster shows the racist trope that a strong enough soap can cleanse a person of his or her blackness. The soap is specifically targeted at those of the laboring class, namely mechanics and housekeepers. Courtesy of Harry Proctor.

According to historian Dana Hale, the most common image of “blackness” during the Third Republic was that of a “black head in silhouette, full view, or profile on trademarks and advertising.” The most prominent features were lips, teeth, and hair, features that Europeans saw as distinct from their own, and the most recognizable “African characteristic” was that of overly exaggerated lips. In many scientific circles, eugenicists used Africans’ pronounced lips as “evidence” that they were morally deficient and less evolved than Europeans.129 In the image from L’Illustration, the “blackened” miners’ lips are pronounced, and their hair is short, receding, and curled (figure 10). They bear a closer resemblance to African caricatures (figure 13) than to either the French rescuer with the lantern entering from the right or the same miners as drawn by an artist from another French paper (figure 11). A comparison with another contemporary image of the same rescue found in Le Petit Parisien makes apparent the host of racial and class-based stereotypes informing the image in L’Illustration. Unlike the miners in the image from Le Petit Parisien, those in L’Illustration are shirtless, barefoot, and bereft of any safety gear, suggesting the miners’ inability to take care of themselves as well as their savagery and stupidity. As Dana Hale reminds us, nudity and near-nudity represented African savagery in the press, scientific journals, travel books, and commercial advertisements. The racialized image from L’Illustration, therefore, would have reminded nineteenth-century viewers of the racist caricatures found in bourgeois encyclopedias and advertisements, as well as the common depictions of the mulâtresses and négresses found in colonial periodicals like Les Tablettes Coloniales.

A month after the explosion, writers in L’Illustration were calling for a continued parliamentary inquiry into the causes of the explosion, with the hope that better safety precautions could be taken to prevent another catastrophe. The victims could not recall what had sparked the explosion, so investigators resorted to interrogating workers on their daily routines to ensure that proper safety protocol had been followed. The subtext was that the workers had brought it on themselves—as evidenced by the lack of safety gear, let alone clothing, on the workers in the drawing from L’Illustration. A similar sentiment echoed throughout the metropole regarding the Fort-de-France fire, for many saw Fort-de-France as underprepared and full of civil and political unrest, and some went so far as to claim that the Martiniquais helped the fire along, acting, in a sense, as the petroleuses did during the Paris Commune.

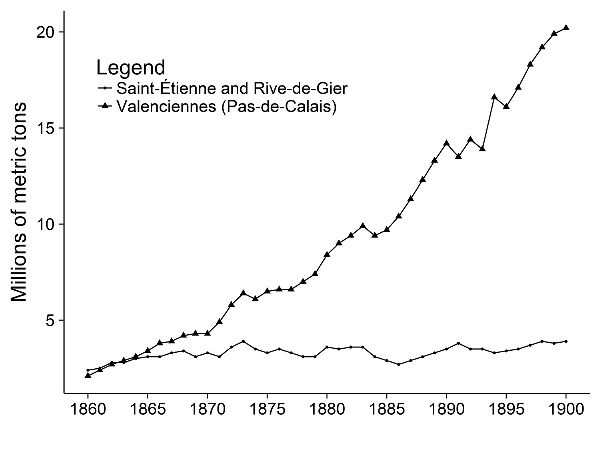

Just like the French Antilles, Saint-Étienne experienced a large disaster at a time when it was declining in relative economic importance. As the French Antilles were once the primary producer of French sugar, Saint-Étienne was once France’s premier coal-producing region. Both gave way to newer, less expensive production (figure 14). Sugar production shifted from cane plantations in the Caribbean to beet sugar refineries in Europe (figure 15). And though coal production and consumption were on the rise at the close of the century, the locus of the coal industry had relocated from the Centre region to collieries in the Nord region, particularly at Pas-de-Calais.130 Prior to 1863, Saint-Étienne and the nearby Rive-de-Gier had been the primary coal fields in France, but by 1903, 64.5 percent of all coal production in France was coming from the Valenciennes fields in Pas-de-Calais.131