4

The Political Summation

Incendiarism, Civil Unrest, and Legislative Catastrophe at the Turn of the Century

At the close of the nineteenth century, the French Caribbean’s black laboring class chafed under the control of colonial bureaucrats ever preoccupied with the bottom line in the islands. Even the islands’ minor products (fruit, cocoa, coffee, and tafia) gained more attention than human suffering in the face of natural disasters, and reasonable and fair wages merited still less attention. Many in the French bureaucracy shared the disdain and disregard that colonial inspectors like Chaudié displayed toward the island’s black laboring class. Whereas metropolitan officials had couched their racism in economic language during the 1891 hurricane, many now explained away the islands’ political strife as outright racial conflict, owing to the large entry of black citizens into the political sphere and the rising specter of socialism in the years following the hurricane.1 The international decline of the cane sugar market worsened standards of living and lowered wages for the islands’ workers, who had begun to form labor unions and mutual aid societies following their legalization in 1884. For instance, Martinique’s first union formed in 1886, while Guadeloupe’s first socialist paper, Le Peuple, appeared in 1891.2

Guadeloupe had hit a rough patch by 1899, and it seemed that nature and the global economy had it in for the small Caribbean island. As the island’s deputy Gerville-Réache put it following an earthquake in 1897, “there are very few countries so cruelly afflicted in a half-century . . . : the earthquake of 8 February 1843, the hurricane and floods of 1865, the cholera epidemic that same year, the fire of 18 July 1871, several yellow fever epidemics, the sugar crises of 1883 and 1895, the financial crisis of 1896–1897, and now the earthquake of 29 April 1897. All these calamities . . . seem to have been conjured up to bring about the island’s demise.”3 In this case, however, it wasn’t darkest before the dawn. Though the earthquake killed few—only four died, with about forty wounded—it destroyed the infrastructure of Point-a-Pitre: the port’s quay walls destroyed by the shaking and perturbed sea, homes in crumbles, and the island’s commerce in shambles. Combined with numerous catastrophes in the long term, as well as a prolonged drought in the short term, the end of the nineteenth century was a bad row for Guadeloupe economically. As Senator Alexandre Isaac put it, “the earthquake had struck a most foul blow to [Guadeloupe’s] general fortune.”4

Such conditions provide context for two new types of disaster, both political in nature: incendiarism in Guadeloupe, which challenged the political status quo and eventually led to the destruction of the island’s largest city, Pointe-à-Pitre, in 1899, and the general strike of 1900 in Martinique, which intentionally disrupted the island’s sugar economy to raise standards of living for the island’s black laboring class. Natural disasters and civil disorder share many parallels in emergency organization, preparedness, and authority response. From the authorities’ viewpoint, both can be equally disruptive and unforeseen, and both foreground existing socioeconomic and political tensions. The social context within which people act is quite different, however, because an event of civil disorder intentionally challenges the status quo, whereas the impetus following a natural disaster is either to return to the status quo or to refashion the afflicted society in the authorities’ image.

Incendiarism in Guadeloupe and workers’ agitation in Martinique prompted a political disaster in 1900, when Antillean politics became embroiled in the culture and politics of a fin-de-siècle France riddled with labor unrest and a rising demand for social justice. The 1899 fire reached a prominence heretofore unseen because of its physical scale, and because it stoked the administration’s and the sugar lobby’s fears of criminal activity among Guadeloupe’s Indian immigrant and black laboring population. The fire came at a pivotal and difficult time in Guadeloupe’s history when the Antilleans’ overlapping class and racial divisions erupted into outright conflict.5 A hurricane in August 1899, which killed sixty-three individuals and destroyed the year’s sugar harvest, made issues worse by, in the words of the finance minister, “augmenting the already large misery [from the fire] in our colony.”6 The sugar crisis compounded this misery, prompting the French Caribbean’s first general strike the following year, which entangled Antillean collective action in metropolitan debates about labor unrest and issues of social welfare, nearly toppling France’s coalition government and precipitating the identification of socialists in the metropole with black laborers in the Caribbean. Incendiarism and the strike in 1900 forced the central government and the island’s administration to cease talking about disaster relief and Antillean rights in coded language and instead address racial and class dynamics outright, not just in the Caribbean but in mainland France as well.

Key to this conflict was the rising prominence of Guadeloupean socialist Hégésippe Légitimus, who had begun to fight for the rights of the island’s black population. Politics on the island had changed, much to the alarm of the government. As the governor of Guadeloupe—none other than Corsican-born Delphino Moracchini, who had led the relief efforts in Martinique in 1890 and acted as governor during the 1891 hurricane—put it, “Blacks had for a long time been docile, passive, and not taking part in politics except to vote for this or that candidate, white or of color.”7 What had changed, according to the governor, was how black politicians now pandered to a black electorate that excluded white people, while exciting the black masses to action with promises to help them rise above their station. For alarmists like the governor, race solidarity had trumped “true” republican beliefs, as the black electorate voted strictly for people “of their color.” This had ushered in an age of political dissension, wherein blacks assumed local offices with “an exaggerated sense of dignity and independence” that engendered a “lack of respect for employers.”8 Such fears were not isolated to worrisome republicans. The rise of the island’s black socialists concerned traditional leftists as well, because the Guadeloupean version of socialism revolved around racial identity and the right wing took the bad publicity as an opportunity to lambast the left’s ultimate class-based goals. In 1899 Alexandre Isaac, the longtime left-wing senator from Guadeloupe who had himself run afoul of the socialists under Légitimus, proclaimed that “the socialists of France and the false socialists of Guadeloupe have nothing in common,” to which right-winger Charles le Cour-Grandmaison responded that one “is the copy of the other!”9 The black socialists in Guadeloupe had been fighting for their place among the socialists of France, proclaiming that “the blood of the black is as red as that of the 71 massacred individuals at Fourmis”—referring to the city of Fourmies in Le Nord, France, where police opened fire on labor demonstrators in 1891.10 The socialist newspaper Le Peuple, which Légitimus himself edited, depicted racial hatred as inimical to real progress on the island and emblematic of historic regression, as those on the right “want the blacks to return to being simple beasts of burden.” This attempt to roll back the clock and scale back blacks’ rights yielded cries of “Down with the Black! Long live the Reaction!”11 In a political climate marked by a socialist ascendancy, a liberal distrust, and a conservative backlash, incendiarism in Guadeloupe, as well as the general strike of 1900 in Martinique, represented a moment of both physical and political disaster in the colony as well as in the metropole.

Under Pressure: The Troubled Year of 1898

At the close of the nineteenth century, the island of Guadeloupe repeatedly erupted into flames—both literally and figuratively. Contemporary observers had begun to treat this as inevitable even before the largest urban fire to afflict the island of Guadeloupe in at least thirty years occurred in April 1899.12 Guadeloupe, like much of the Caribbean, was not unfamiliar with fires. Several of the island’s towns had at one time or another been set aflame: Grand-Bourg in 1838, Basse-Terre in 1844, Port-Louis in 1856 and again in 1890, Le Moule in 1873 as well as 1897, and Pointe-à-Pitre in 1871 and 1899. Fires restricted to small homes and isolated cane fields were a mainstay of life on the island.13 In 1878, for instance, there were seventy-four fires in Pointe-à-Pitre alone, and in 1879 there were sixty-four, several of them fires set to harvests in the cane fields. Many of these were incendiarism aimed at political protest, but no further collective action occurred and the government believed that it had dealt with the protesters swiftly and firmly. Fire starters received punishments varying from eight to twenty years of hard labor, and the fires themselves typically caused little perturbation beyond the initial cleanup.14 In the words of a captain in the French navy, “Pointe-à-Pitre was a tidy and animated city with important commercial functions despite repeated disasters.”15

All this changed by the start of 1898, when tensions began to mount as a number of localized fires and “acts of marauding” menaced the region around Pointe-à-Pitre. According to the béké-dominated newspaper Le Courrier de la Guadeloupe, protestors allegedly cried, “Down with the Whites and Mulattos! Long live the fire!” during a likely accidental fire in May.16 Incidents within Pointe-à-Pitre in June 1898 prompted an investigation by the prosecutor general, who claimed to have found that vagabonds had ignited a fire in an under-construction home as well as a warehouse, and that indentured immigrants had burned down a church. No one was caught or tried in any of the cases, since, in the words of the prosecutor general, incendiarism “is a crime that most often escapes justice.”17 And yet the French and local government bemoaned that discontent among out-of-work and migrant workers sowed instability among Guadeloupe’s population, particularly as fires spread to plantations on the northern end of the island by the month’s end. In fact, enough fires had been set in and around Pointe-à-Pitre to prompt the French navy to send a warship to the island to calm a population stirred by the “malevolence” of “isolated miscreants and black conspirators,” as well as by the Indian immigrants that planters had brought to the island as indentured servants to help with sugar cultivation.18

Between 1853 and 1889, roughly fifty thousand indentured servants had been brought to Guadeloupe from India, Africa, and China, of whom nearly sixteen thousand remained living in the colony.19 The rest had been repatriated. Most of these immigrants in Guadeloupe (roughly 85 percent) were from India, as French authorities brought exclusively East Indians to Guadeloupe during the Third Republic to keep down labor costs by skirting planters’ reliance on free black workers.20 This action sowed discord between the island’s black laboring class and the indentured servants, and in 1888, British authorities outlawed Indian immigration into the French Antilles due to civil strife. The final group of Indian indentured servants arriving in 1889 were facing repatriation after finishing their ten-year contracts by 1899, prompting them to acts of civil disobedience alongside the black laborers. Both groups felt disenfranchised: the former by their contracts and circumscribed legal status, and the latter by their economic situation.21 In response, the prosecutor general urged the local government to prosecute the fire starters “with great diligence” and to catch their accomplices, lest the mounting “inquietude” continue as workers become increasingly “jealous of their neighbors.”22 Such increased military presence did little to enervate the islanders’ spirit. If anything, it threw fuel on the fire and alienated potential allies among Guadeloupe’s republicans, who voiced a firm opposition to the presence of “warships [that] have entered into our ports . . . [with] cannons pointed at our unfortunate land.”23 Many more would later sign a petition to the Ministry of the Colonies to cease military interventionism in July 1899.24

When a storefront burned down in December 1898 due to unknown causes, likely an employee who neglected to extinguish a candle upon closing the store, local merchants demanded police find someone responsible despite the lack of concrete evidence.25 In response the governor wrote to the minister of the colonies to complain about the insufficient funding of the police force in Pointe-à-Pitre, arguing that the law of 5 April 1844 had hamstrung local law enforcement by placing its funding and direction on the shoulders of the communes themselves. The metropolitan law, which was specifically extended to Martinique and Guadeloupe, had been designed to standardize the organization of municipalities across France with a locally elected mayor and legislative council, and to ensure that each commune would be subjected to the same juridical regime. In effect, however, it meant that in colonial Martinique and Guadeloupe, central funding and direction for the police force had ceased. Enforcement thus fell to the local police departments, largely because the national public safety force, or gendarmerie, was virtually nonexistent in Guadeloupe—a military detachment of only 120 surveilled an island of 170,000.26 The reliance on local police forces wrested control from the colonial governor’s office—a conflict in play in the disasters of 1890 and 1891, when the governor stood at odds with Martinique’s communal governments. In this instance, officials saw discord between public safety and the public itself—between the appointed and elected government—arguing that locally chosen juries consisting of nègres were not impartial and thus repeatedly acquitted, and perhaps sympathized with, known criminals.

This antagonism extended to the relationship between the gubernatorial office and the mayors themselves. For example, the governor believed that the mayor of Morne-à-l’Eau—a “black” in the words of Moracchini—had misrepresented the tranquility of his commune when asked point-blank about incendiarism there, allowing discontentment to fester rather than alerting the authorities.27 The central government in Paris shared Moracchini’s distrust of the local government. According to the minister of the colonies in Paris, dissatisfaction had multiplied because “certain weakness in the suppression of crimes reigns in all of Guadeloupe.”28 As was the case in the 1891 hurricane, the metropolitan government believed that locally elected officials—increasingly people of color—could not be trusted with the affairs of state, because local officials sympathized with their constituents who acted against labor practices. That the governor and the ministry had no direct authority to easily oust rightfully elected representatives by French citizens irritated them.

The political climate worsened in 1899 when alleged arsonists with “unclear motives,” according to governmental officials, attempted to start three urban fires in late February, as well as several more fires in the cane fields outside town. Many on the left saw those arrested as scapegoats, sacrificed in the name of public order, while the rich white proprietors of the sugar plantations and factories in Guadeloupe were the real villains.29 To put it bluntly, both leftist republicans and socialists held a strong distrust of “reactionary officials,” like the prosecutor general, who were all too willing to cry foul at the left. Turning a blind eye to the social inequities the island’s left-leaning political parties highlighted, some officials claimed not to understand why incendiarism seemed to be on the rise, leading the prosecutor general, P. Girard, to ask “[W]ere these attempts committed with the intention of benefiting from terror and panic to pillage . . . to sow desolation and ruin among the rich as well as the poor?”30 For such officials the specter of riotous, illogical mob behavior, and not any deeper societal cause or inequity, loomed behind the rash of fires.

Others, however, were more astute. The governor of Guadeloupe, Delphino Moracchini, had extensive experience with disasters and conflict in both Antillean islands, having been Martinique’s public official in charge of distributing relief supplies during the fire of 1890 and the governor who oversaw the relief effort after the 1891 hurricane. He became governor of Guadeloupe in 1895 and had already dealt with a number of smaller incidents of arson, as well as the 1897 earthquake that killed six, wounded forty-two, and caused roughly five million francs’ worth of damage.31 Though his prejudices at times led him to take a hard-nosed approach toward the Antillean population under his charge, his experience and republican convictions nevertheless gave him a sense of the pulse of the people, and in 1899 he noted how an inequitable exchange rate had sowed misery among the islands’ poor by increasing the cost of food and consumer products.

Repeated natural disasters had already amplified Guadeloupeans’ economic misery, such as when the 1891 hurricane doubled the price of islanders’ principal food crop, manioc. By 1899 the Méline tariff had for years strained the working poor by increasing the cost of imported goods, and now it was accompanied by a debased Guadeloupean currency. Under the Third Republic, each colony in the French empire, Guadeloupe included, had its own wholly independent currency issued by private colonial banks tasked with providing credit to local agricultural and industrial endeavors. These colonial currencies were exchanged with the metropolitan franc according to market forces. When trade between metropole and colony was balanced, the two currencies traded at a one-to-one ratio. However, when trade dropped and the colony entered a deficit, its currency depreciated against the metropolitan franc.32 Thus colonial banks fulfilled another vital function: negotiating currency exchange contracts with metropolitan financial institutions. In their negotiating, colonial banks could financially engineer the exchange rates to some degree to offset what they saw as detrimental market forces.

To this end, under pressure from factory owners facing declining profits and a mounting trade deficit, the Banque de la Guadeloupe made market prime adjustments in 1897 to favor the sugar industry. Their adjustments colluded with a market downturn to dramatically debase Guadeloupe’s currency, which dropped by more than a quarter of its value as the exchange rate skyrocketed from just 2 percent in 1894 from to over 30 percent in 1897.33 Given the political fallout and the divisions it underscored between the island’s wealthy békés and working class, historian Christian Schnakenbourg has deemed the 1897 exchange rate hike to be the “detonator of the wider political crisis” of the decade to follow, because it grossly favored a wealthy minority while dispossessing the poor majority, and because it led to the first rupture between the island’s white business elite and the metropolitan government’s appointed administration—namely Governor Moracchini—since the abolition of slavery nearly forty years prior.34

The colonial bank’s maneuvering aimed to create a favorable balance of trade and ensure financial liquidity, for the benefit of the bank’s shareholders and customers but at the expense of the island’s working population. As one French colonial journalist, Henri Desroches, explained, “In principle, the Bank should therefore push the exchange rate as high as possible, even if the interests of its constituents are absolutely contrary to those of the majority of the population.”35 A high exchange rate weakened the island’s currency, which in turn increased both incomes and tax receipts by inflating the Guadeloupean franc. The weakened franc also increased exports, because Guadeloupean goods were now comparatively cheaper. Since debt balances remained flat as currency became easier to come by, inflation further privileged the sugar elite by making it easier for them to repay the debts they had accrued in expanding and retooling Guadeloupe’s sugar production since 1870. In turn, the repayment of debts helped the colonial bank by securing cash flow and ensuring the opening of new credit accounts.36

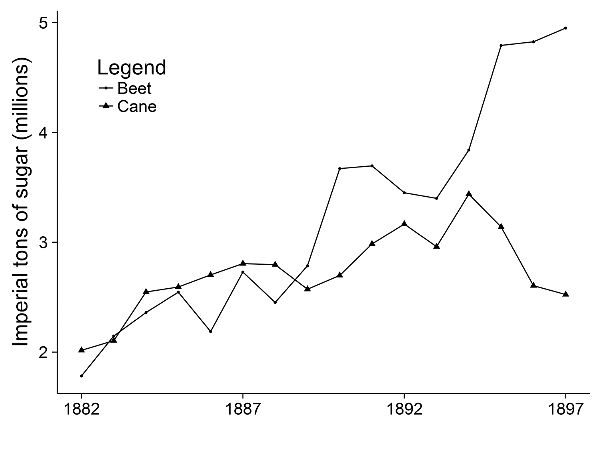

On the other hand, the weakened Guadeloupean currency burdened sugar workers by decreasing the value of their labor, and it disadvantaged the poor by increasing the cost of food, which was largely imported. Consequently the islands’ republican representatives, led by mulatto deputy Gaston Gerville-Réache, vehemently opposed the forced devaluation of the Guadeloupean franc, for, as Governor Moracchini estimated, by 1899 local merchants had marked up their products by as much as 50 percent to offset the increased costs of imported goods.37 An exchange rate of 30 percent meant that a worker’s daily pay of 1 franc 25 centimes was in reality worth only 88 centimes, because the weakened currency simply could not purchase as much nutrition as it once had.38 Some agricultural workers in Guadeloupe earned as little as one franc per day, perhaps as high as one franc fifty centimes, depending on employment.39 Underpaid workers turned away from imported goods and began consuming more locally obtained foodstuffs like manioc, which in turn drove their prices upward.40 For instance, the price of a kilogram of cod increased to one franc sixty centimes—potentially over 150 percent of workers’ daily wage.41 While the bank maneuvered to increase the exchange rate in the hope of boosting Guadeloupean exports, which saw limited effect (figure 17), the price hike in foodstuffs deepened the desperation among workers and their families for whom the years-long downturn in the sugar economy had already translated into unemployment for some and fewer workdays for others.

Fig. 17. Sugar production in Guadeloupe, 1880–1905

With the ascendancy of beet sugar, Guadeloupe, like Martinique, witnessed a steep decline in its sugar production by the 1890s, so that by 1900 the island produced half the tonnage it had produced ten years earlier. Graph created in R statistical package with data from France, Annuaire statistique 15:734; Rolph, Something about Sugar, 242.

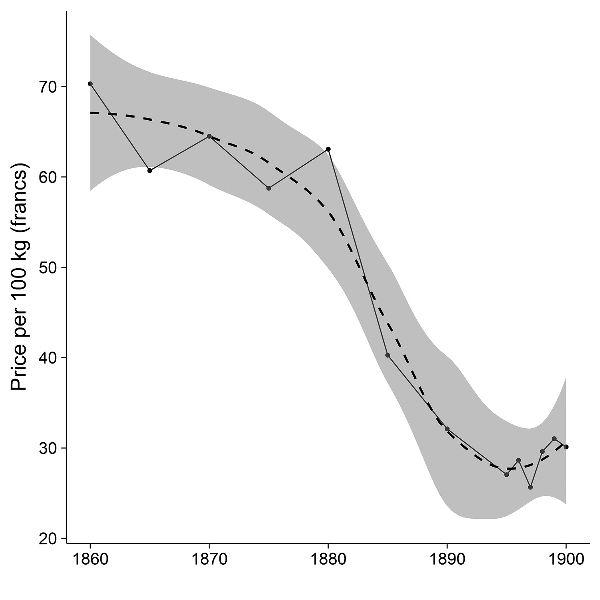

Despite the changes to the exchange rate and the colonial bank’s attempts to mitigate the island’s trade deficit, the sugar industry in Guadeloupe continued to falter. By 1890, Europe and to a lesser extent the entire world had shifted away from cane cultivation toward beet sugar, a more lucrative and efficient product than cane sugar. Though worldwide cane sugar production remained relatively stable between 1882 and 1897, beet sugar saw a meteoric rise, growing 280 percent over fifteen years (figure 18). This drove the worldwide price of sugar downward, a blow to Guadeloupe’s sugar industry. Falling revenue led to a drop from fifty-seven million kilograms to just shy of forty million kilograms in sugar production in Guadeloupe between 1882 and 1899. Moreover, the island had seen four massive sugar shortfalls due to storms and hurricanes in 1885, 1891, 1894, and again in 1899. While all three of the island’s largest sugar companies had seen a profit in 1899, they had struggled for nearly fifteen years. Worse, a poor harvest in 1900 due to incendiarism, drought, and the hurricane in August 1899, producing eleven million fewer kilograms than the prior year’s harvest, wiped away the 1899 profits.42 By 1900 the islands’ three largest sugar producers had seen a net loss of nearly 1.8 million francs since 1882 and they owed about twice that figure (3.6 million francs) to creditors—again, reason for them to support increasing Guadeloupe’s exchange rate. The largest central sugar factory, Usine d’Arboussier, had also seen a decline in profits; from 1876 to 1883, it received approximately 53.10 francs per thousand kilograms of sugar, while from 1894 to 1899 this figure dropped to 37.75 francs per thousand kilograms.43 Guadeloupe’s sugar industry was deeply under water.

Fig. 18. Worldwide sugar production, 1882–97

By the close of the nineteenth century, beet sugar had far surpassed sugar cane production worldwide. Whereas production levels of beet and cane sugar had been roughly equal in 1882, the world produced twice as much beet sugar as cane sugar by 1897. Graph created in R statistical package with data from U.S. Department of State, Commercial Relations, 551–54.

Fig. 19. Price of unrefined sugar in France, 1860–1900

With a worldwide surplus of sugar, the price of raw sugar in France dropped dramatically over the second half of the nineteenth century, further distressing the economies of Martinique and Guadeloupe, which relied heavily on a sugar monoculture. Local regression trend line (LOESS). Graph created in R statistical package with data from Hélot, Le sucre de betterave, 212.

Guadeloupe’s representatives had brought the monetary crisis in the Antilles to the Senate floor numerous times, most recently in March 1898 when Senator Alexandre Isaac—one of Guadeloupe’s most prominent men of color—asserted that France had created the islands’ sugar crisis by cultivating beets and by not adequately providing support following “public disasters, earthquakes, [and] fires, that have exhausted its last resources . . . [and] caused a monetary crisis more serious than all those preceding it.”44 Despite his advocacy, little had changed one year later, and the colonies remained, in the words of Isaac, “totally forgotten and even more totally neglected.” The government was torn between providing assistance as if the monetary crisis were itself a disaster, and telling individuals to pick themselves up by their own bootstraps—or, in the words of Governor Moracchini, “Help yourself, and heaven will help you!”45 Consequently the people of Guadeloupe believed their voices had been unheard and that they had no recourse to ameliorate their situation. In a moment of clarity one week before the burning down of Pointe-à-Pitre in April 1899, Moracchini remarked that “this mode of vengeance [arson] . . . returns to us from the time when the torch was the only instrument of vengeance left to the slave.”46

By 1900, Europe’s turn to more economical means of producing sugar through beet cultivation, as well as a worldwide surplus of available sugar, had caused a steep decline in the production of the French islands’ major crop: sugar cane. The price of sugar cane had fallen by about 25 francs per hundred kilograms, and Guadeloupe was, according to Senator Isaac, “the colony most mistreated by the crisis.”47 Consequently workers were receiving fewer days on the job, and they blamed the administration for the hardships they met at home. This was particularly true for the immigrants who had been brought to the Antilles after the abolition of slavery as indentured servants to harvest sugar cane; they had no rights beyond those outlined in their work contracts but nevertheless had a history of demanding fair work and pay. By 1880, for example, enough servants had deserted their posts in Martinique to prompt the minister of the interior to ramp up the surveillance efforts of the so-called labor police charged with enforcing the indentured servants’ contracts. The minister encouraged police to search homes and places of work, and he ensured that the names of work deserters appeared in the official governmental newspaper.48

Consequently, by 1899 unrest among indentured servants as well as the island’s black laboring class was a substantial issue—one the conservative party and political infighting in Pointe-à-Pitre made more pronounced. Just two weeks before the fire, Governor Moracchini insisted that Pointe-à-Pitre’s conservative party, which had grown increasingly antagonistic since the application of universal suffrage on the islands, exaggerated the incidents to curry favor with their twenty-five hundred or so members and to drive wedges between the islands’ republicans.49 He voiced his anger with the press for throwing restraint to the wind and publishing passionate, biased commentaries that “excited spirits” on the island.50 Guadeloupe’s republicans also lamented this “reactionary spirit” among employers, which they felt foisted “inequities and horrors . . . [on] a naked proletariat, worn and absolutely disarmed” on the island “as in France.”51 In their eyes, the local conservative press used the island’s colonial, slave history—as well as present-day racism—to lure the metropolitan government into blaming Guadeloupe’s republicans and socialists for asserting their rights as French citizens, in turn causing grave injury to Guadeloupean democracy. Just as in the case of the cultural understanding of Martinique, which pitted republican people of color against an antiquated planter class, Guadeloupe was plagued by intransigent békés who sowed discord—allegedly to cries of “Down with the negro! Down with the Republic!”—in order to roll back the clock to the Ancient Regime—an era that lacked the ideals of “liberty, equality, and fraternity” and precluded emancipation and enfranchisement of the island’s slaves.52 Some went so far as to accuse whites of setting the fires in order to alienate the government from the black population.53 In turn, seeing the recent incendiarism as emblematic of a race war that emancipation had initiated in 1848, the conservative press called the quintessential black laborer a “dirty Negro, sorcerer, thief of Indians, arsonist.”54 By accusing black laborers of recruiting disgruntled East Indians in their machinations against the békés as well as exaggerating the “pillaging of harvests” and the crimes against property, the conservative party hoped to convince the central government to rectify the unfair international and domestic competition that they saw crippling their industry, while at the same time curtailing the rights of people of color, socialists like Légitimus and left-leaning republicans like Gerville-Réache, who had been increasingly obtaining governmental positions since the onset of the Third Republic.

While it was clear that many of the fires were deliberate, it was unclear which exactly could be properly attributed to malfeasance, since in 1899 the island was experiencing such a severe drought that in the words of the prosecutor general to the governor of Guadeloupe, “a poorly extinguished match thrown by a passerby or by a cultivateur would be sufficient to enflame a plantation’s straw.”55 Amplified by the uncertainty, fervor stirred in the colonies as conservatives sought to exploit the situation to roll back tariffs and workers used a slave’s last resort—setting cane fires—to seek a voice in local and metropolitan politics. Many local and metropolitan officials picked up on this tension. Letters between the prosecutor general and the governor show that they were increasingly worried that the arsonists’ motives were political in nature rather than personal vendettas or “jealousy,” rhetoric used by békés to discredit slave resistance prior to emancipation. As evidence mounted that the fires might be—or might become—deliberate acts of political speech, officials now worried that the fires marked the coming of collective action. One letter from the owner of a sugar refinery put it starkly: if salaries did not increase for the workers, there would be no sugar harvest this year. At the close of one workday, he had found in the factory’s scales an anonymous letter, in which one worker asserted, “No government exists that can prevent us from setting fire [to the fields]. Adieu harvest, adieu sugar cane, we cry for you.”56

Despite the warnings, political and social discord continued to rise, and proprietors began to hire private guards to protect their property. At the close of March inhabitants near the Darboussier sugar factory assembled and threw rocks at the employees running the railway, while reports of the theft of sugar cane from large and small proprietors saturated the courts.57 Guadeloupe’s general secretary, Joseph François, endorsed repression, saying only the military “could produce the necessary moral effect” and more aggressive tactics “would intimidate the malefactors and prevent future attacks.”58 Increased repression did little more than stoke the flames of discontent among a population that felt it had a right to protest as much as any in France proper—in the words of the island’s republicans, to safeguard “the republican ideals of justice and social emancipation.”59 By April 1899 things had come to a head.

Fire to the City: The Burning Down of Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe

Shortly after midnight on 18 April 1899, a recently fired employee of a local pharmacy broke in and caused a fire unintentionally, setting the largest town on the island, Pointe-à-Pitre, ablaze.60 As in 1891, powerful Antillean winds fueled the fire, which consumed 313 homes and caused three million francs’ worth of damage. The inferno destroyed roughly one-tenth of the city and left three thousand people without shelter.61 Local Guadeloupean newspapers, as well as the office of the governor, readily pinned this on malfeasance, and the island’s mounting labor unrest amplified the ensuing political fallout.

“The series of criminal fires continues . . . a great inquietude manifests itself,” wrote a Guadeloupean businessman and local councilman in a letter to Alexandre Isaac, the island’s senator who tried to mitigate between the workers and the békés, on the morning after the great fire of Pointe-à-Pitre.62 To many observers, Senator Isaac foremost among them, the fire on the night of 17 April 1899 marked the expression of the mounting discontent among the wider working-class population, and represented the culmination of the island’s growing civil unrest that threatened, in Isaac’s words, “to ruin the city in one night, as had happened in [the fire of] 1871.”63 Landowners, businessmen, and planters demanded the French government protect them from such acts of criminality. They felt, along with Senator Isaac, “entitled as citizens of France to measures of protections.”64 Considering the double threat of civil unrest coupled with natural hazards, investors and creditors alike worried that going to the colonies presented a risk to capital and health perhaps too high for Frenchmen to take.65

Such a sentiment was what had infuriated the workers; that is, workers lamented that Guadeloupe continued to be a colonized space where the concerns of rich investors trumped those of the poor. Many of the island’s poor population supported the seizure of cane from the harvest by workers—the so-called marauding acts—in the name of social justice, just as protesters in the bread riots of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century in England had seized grain in the name of a “just price.”66 When three private watchmen of English descent stopped a creole man in the nearby town of Les Abymes from stealing some cane from the harvest, a crowd of six hundred—the “neighborhood’s entire creole population,” according to reports sent to the minister of the colonies—armed to the teeth with cutlasses and batons marched on the plantation in retaliation, screaming, “Help! To the Assassin!” The angry mob of “creole workers” attacked and vandalized the home of the planter who employed the security guards, chasing the guards indoors and seriously beating them.67 They then proceeded to shatter all the windows, flip over all the furniture, and rip the doors and floorboards from the home and throw them into a nearby cane field. Eleven people were arrested for orchestrating the attacks, and the relationship between the authorities and the wider population had reached its breaking point. When the courts handed down a guilty verdict to four of the crowd, judges reputedly blamed it on “the prevailing unwholesome excitement, more or less fomented by a Socialist propaganda.”68 After the great fire, rumors spread that Pointe-à-Pitre’s denizens were antagonistic toward the firefighters and rescue personnel, thwarting efforts to extinguish the fire in order to voice their dissatisfaction.69 These rumors built on the narrative established by the government that the islanders were themselves the incendiaires who wished to burn the island’s establishment to the ground.

The fact that the incendiarism did not cease on the night of 17 April supported the officials’ accusation. While the rubble in Pointe-à-Pitre still fumed, a man disguised as a woman and armed with a cutlass—reminiscent of the petroleuses who set buildings aflame to protest the end of the Franco-Prussian War and voice their dissatisfaction with the founding of the Third Republic during the Paris Commune—attempted to burn down a store on 19 April.70 More unidentified persons set fire to wealthy homes in the neighboring towns of Sainte-Rose, Port-Louis, and Grand-Bourg. At Sainte-Rose, roughly fifty soldiers and mariners from a steamship helped extinguish the fire, and then arrested about a dozen people—one of whom had a stick of dynamite. In the coming weeks, five additional sugar fields and six refineries went up in flames.71 In one such instance near the town of Morne-à-L’Eau, local authorities sentenced three individuals—two Indian indentured servants and one black laborer—to ten years’ hard labor.72 The gendarmerie and Guadeloupe’s leadership feared that continued civil unrest threatened to reduce the island’s sugar economy to ashes, while Governor Moracchini attempted to project a veneer of calm on the island’s population, promising that “tranquility reigns in all the towns he visited.”73 This did not assuage local anxieties over the civil unrest, and one Guadeloupean newspaper lampooned Moracchini by sarcastically claiming that “the arsonists are tranquilly continuing their work of destruction in Pointe-à-Pitre as well as in other towns.”74

Behind closed doors, Moracchini had a more nuanced understanding of the root causes behind the recent outbreak of fires, and he argued that mere repression would not be sufficient to quell the unrest. Shortly after the 1899 fire, he wrote, “It is incontestable that fire has been here an instrument of vengeance of the workers against their employers from time immemorial. . . . We are experiencing an outbreak [of such activity.] . . . The cause? Political excitations say some; the misery caused by the exchange rate that has increased prices across the board to previously unknown heights, say the others.”75 Moracchini advocated the creation of small landholdings among the laboring black class to isolate them from the whims of the international market and inequitable customs duties, arguing that “the solution to the economic and social problem in Guadeloupe is the creation of small proprietorships” by “giving land to the proletarians to create . . . their own livelihood . . . as exists in France.”76 Such an idea had been prevalent in the mainland at this time as a solution to metropolitan labor unrest.77 Republican Guadeloupeans—united in a common goal of “the moral aggrandizement of France”—demanded the rectification of the island’s inequities, writing to the president of the Republic in January 1900 to express their support for the eight-hour workday, the superiority of civil diplomacy over military might, and the continuation of the 1884 law that allowed for the organization of labor unions.78 All of these demands resonated with the islands’ metropolitan brethren, mostly coal miners and smelters, who continuously launched strikes throughout the first two decades of the twentieth century—including a general strike in 1906 for the support of the eight-hour workday.79

Therefore, while Moracchini attributed the recent wave of incendiarism to local political excitations and the exchange rate, he also saw workers’ discontent as part of larger “social problems” plaguing France and the rest of Europe where “a similar state of things has produced terrible strikes,” leading him to ask, “Why is criminality on the rise in France [as in Guadeloupe]?”80 According to the Guadeloupean left, who referred to themselves as “citizen-electors,” metropolitan workers’ agitation—what Moracchini called criminality—had inspired the island’s proletarians with their own struggle for rights and social justice, and vice versa. The struggle for equality in the face of inequity in the Caribbean as in Europe was mutually reinforcing. Workers demanded the ear of the state, claiming that “universal suffrage must be respected in Guadeloupe as in France.”81 To Moracchini and many others, it seemed that through incendiarism Guadeloupeans were participating in a widespread phenomenon in France at the turn of the century, as anarchists turned arsonists and used fire to voice their discontent with the French government—and indeed all governments everywhere. For instance, August Valliant lobbed a nail bomb at the French Chamber of Deputies in December 1893, shouting, “Death to the Bourgeoisie! Long live Anarchy!,” at his hanging.82 His infamous attack inspired Émile Henry to detonate, three months later, a bomb that killed one and wounded twenty in a café at the Gare Saint-Lazarre train station in northwestern Paris, largely to protest the division of Paris into two cities: one inhabited by the “haves” and the other by the “have-nots.”83 That same year another French anarchist, Martial Bourdin, carried out a suicide bombing outside the Greenwich Observatory in the United Kingdom, and an Italian anarchist assassinated French president Marie François Sadi Carnot. Drawing on a history of anarchism dating back to Proudhon’s famous declaration that “property is theft” in 1840, the wave of prominent anarchist attacks in fin-de-siècle Paris, where nearly one in ten people were jobless and many worked eighteen-hour days, led Senator Isaac to claim, “It’s the époque where great attacks take place in France, and it seems in this moment that some people feel disposed, in Guadeloupe, to imitate the authors of such attacks.”84 Indeed one Parisian bank observed, “The inhabitants show themselves more and more frightened by the progress [in Guadeloupe] of anarchist propaganda.”85 For better or worse, physical distance had not isolated Guadeloupe from the ideological strife that characterized France at the end of the century. Moracchini was thankful that strike activity had not yet manifested itself in Guadeloupe, though, unbeknownst to him, such a strike was just over the horizon on Guadeloupe’s sister island of Martinique.

Fire and Water Yield Steam: The Hurricane of 7 August 1899

At 11 a.m. on 7 August 1899, a category four hurricane struck Guadeloupe—the worst storm to affect the island in eight decades. When the waters from the storm hit the broiling frustration of the islands’ working class, discontentment skyrocketed in the French Caribbean. Contemporaries saw natural disasters and civil disorder as inherently linked—one mutually reinforcing the other. As the left-wing-coalition republican journal La Cravache stated, “To the natural scourges that strike it [Guadeloupe] and cut into its material prosperity each day, we must add the plagues of order and different natures which ruin its moral prosperity.”86 Since the proclamation of the Republic in 1870, the colony had received no respite from earthquakes, fire, and cholera outbreaks, which had fueled the discord between the “different natures” of Guadeloupe: reactionary whites, mulatto liberals, and socialist blacks. Some on the island sought a rapprochement between republicans and socialists, since disastrous events had allowed divisions to grow between the three main political groups and opened the door to a reactionism that relied on the old adage “divide and conquer.”

Despite the terrible strength of the storm, which had wind speeds of upwards of 150 miles per hour, the overall physical damage on the islands was limited, because the storm had grazed the island on its northern side.87 Officials were grateful that the economic damage was far less than Martinique had suffered in 1891, which had set back sugar production by roughly five years. From a humanitarian standpoint, however, sixty-three people died during the tempest in August 1899, and damage was concentrated in six towns: Le Moule, Anse Bertrand, Port-Louis, Petit Canal, Morne-à-l’Eau, and the outlying island La Désirade—all, with the exception of La Désirade, sugar-growing sites of civil discontent and incendiarism in the preceding months.88 In other words, the area that had just burned was the hardest hit, virtually destroying Pointe-à-Pitre and its environs, with buildings tossed one over the other and entire livelihoods lost in a matter of hours. In Le Moule, where fire had ravaged the town in 1897, the storm surge completely submerged the oldest part of the city and the wind had, in the words of one observer, displaced houses as far as an entire block.”89 Likewise, water completely enveloped Port-Louis, and nothing was left of Anse-Bertrand.

The impact of the storm on the coffee and cacao harvest, as well as on the morale of the people, was substantial. The drought that worsened the fires had severely constrained the sugar crop, leaving it so small that the storm had little impact. But the light damage—in places the cane stalks’ roots had been ripped up, which meant potentially decreased harvest in future years—further distressed workers concerned that the already small harvest would now be infinitesimal, which would further decrease their paid days of work.90 Powerful winds had overturned nearly all the homes of the islands’ agricultural workers and small cultivateurs—largely because these homes were little more than hovels pieced together with nearby materials, which could not withstand the strong gusts. In other words, the storm had left destitute the island’s small-time farmers and agricultural workers, whom Moracchini claimed were the most affected and had little in savings. Moreover, the manioc crop, Guadeloupeans’ primary food, had been lost, which further exacerbated the rising food prices on the islands.91 The very workers who had grown so dissatisfied with their government bore the brunt of the destruction, leaving them with few resources and little motivation to continue the civil unrest that had marked the year prior. The storm sapped their incendiary spirit.

Moracchini opened up a provisionary credit of thirty thousand francs to purchase necessary foodstuffs to alleviate suffering across the island, particularly in the north, while the metropolitan government opened a line of credit for the colony in the amount of three hundred thousand francs, of which sixty thousand had been earmarked for the purchase and transport of food and other necessities.92 The metropolitan government charged the colony’s line of credit sixty thousand francs for several shipments of flour, biscuits, rice, red beans, cod, and salted beef, leaving the local government with 240,000 francs to provide assistance and offset budgetary losses.93 Moracchini also offered a small “salary” to help the afflicted purchase necessities, and he began distributing food and clothing to the worst-hit areas, distributing the supplies as he saw fit. For instance, Port-Louis’s and Le Moule’s inhabitants received monetary aid to purchase clothing, since “in these two communes very little of the population lived off products destroyed by the hurricane.”94 Moracchini admitted, however, that no matter how much care was taken in distributing the aid, “some abuses are inevitable.”95 As in the 1890 fire, many saw the distribution of aid as inequitable and, in the words of the socialist press, slanted toward the friends of local officials and those workers who fell in line with the sugar industry’s wishes. In other words, the socialist press saw the distribution of aid as a form of social control by the sugar industry, whom the press described as “pimps” who “exploit once again the ‘naiveté’ and misery” of the victims following disaster.96 Colonial societies and the planter lobby echoed such negativity, blaming Moracchini for his “strange and culpable apathy” and calling for him to be removed from office, partly because of the hurricane and partly because they considered his response to the fire to be at best insufficient and at worst “an odious revolutionary campaign.”97 The historic record does not establish whether food distributors committed malfeasance, as workers accused, nor is it the real issue; rather, the utterance of the rumor highlighted the social discord and distrust between the populace and the government.

As was the case of the 1891 hurricane and would be the case of the 1902 eruption of Mount Pelée, the storm did not affect everyone equally. Whereas workers and poor cultivateurs had been hit the hardest, their sole recourse for compensation lay in the public dole: the foodstuffs, supplies, and money that Moracchini distributed to help the poor rebuild. He set aside some of the money for helping to turn homes upright and return the poor to some sort of shelter, which might be the hovel in which they lived before the storm. Whereas Guadeloupe’s proletarians had nothing to indemnify with lucrative insurance policies—they had nothing to their name aside from their ability to perform labor—the more well-to-do, particularly plantation owners and property managers, had recourse to insurance indemnities that helped them rebuild.98 As is common following disasters, the poor bore the brunt of the physical costs of the disaster and the rich the financial, and reconstruction efforts therefore privileged the rich. The island’s republicans therefore complained that “in rich neighborhoods . . . homes are insured for 5 to 6 times their value.”99

Guadeloupe’s local government requested a loan of three million francs “destined to go to proprietors ruined by the cyclone . . . to rebuild their devastated properties.” The interest-free loan was to be drawn on metropolitan accounts, and individual borrowers, who were expected to repay the loan over the course of twenty annuity payments, received the funds.100 Victims of the fire in April received nothing, much to the chagrin of Deputy Gerville-Réache, and only those who could demonstrate concrete material losses from the hurricane and guarantee the loan’s repayment would have had access to funds. Gerville-Réache deemed the ploy a “very weak alleviation for the incalculable suffering” on the island, though he nevertheless advocated it as a stopgap measure to the minister of the colonies.101 The metropolitan government rejected even this “very weak alleviation,” deeming it unnecessary to the “reconstruction of the colony.”102 Having left the island with too little resources—to the extent that the U.S. Department of State deemed the French government’s aid “utterly insufficient, considering the widespread character of the disaster”—the hurricane had magnified the societal inequity that plagued the island prior to its arrival.103

While the hurricane had amplified the suffering of the islands’ working class, it had dampened the workers’ incendiary spirit. Though workers’ activities had undermined the legitimacy of Moracchini in the eyes of colonial societies like that of Le Havre and financial interests like the Chamber of Commerce of Bordeaux, who saw the governor as a colonial shill with neither the power nor the courage to quell local resistance and secure their financial interests, workers’ frustrations never coalesced into an organized strike that would capture the metropolitan imagination.104 This is not to say that there were no work stoppages connected to the unrest of 1899—to the contrary, four hundred workers at the Darboussier factory as well as two hundred workers in Lamentin and Pointe-à-Pitre ceased work in protest during March of the following year—but the sporadic and isolated workers’ agitation never blossomed into an island-wide strike.105 The hurricane aside, the lack of island-wide organization had several causes. Guadeloupe’s unions and mutual aid societies had been reluctant to push for strikes, as they strained the relationship between union leadership, elected representatives, and the metropolitan government.106 Moreover, scholar Philippe Cherdieu has deemed Guadeloupe over this period to be “the failure of colonial socialism” in light of what he saw as Guadeloupe’s weak union leadership and its lack of a true urban proletariat.107 Although the workers’ movement in Guadeloupe predated that in Martinique by over a decade, the island’s socialist leaders failed to mobilize workers along class-conscious lines, and instead formed a movement around nègrisme that was antagonistic toward whites and mulattos alike.108 Fearful of a Haitian-style revolution, planters and governmental officials in turn did not hesitate to employ military force to keep workers in check. Consequently, Guadeloupe would not see its own large-scale, economy-stopping general strike for another decade, when demonstrating workers brought the island’s sugar production to a standstill in 1910.

The hurricane had not quenched the incendiary spirit on Guadeloupe’s sister island of Martinique, which had been experiencing similar economic hardships at the hands of the sugar crisis. Not only was Martinique spared the brunt of the passing storm, but it was also where workers’ frustrations coalesced into a widespread strike in which nearly the entire working population participated. On an island closely connected to metropolitan politics via an interstitial and politically engaged mulatto class, a direct confrontation between the Caribbean’s working and ruling classes was at hand. While incendiarism in Guadeloupe had strained the island’s relationship with the metropole and eroded administrators’ trust in black Guadeloupeans’ citizenship, the strike in Martinique would become embroiled in metropolitan politics, consequently threaten the stability of the Parisian administration, and further socialists’ coidentification between labor troubles in mainland France and those on the island.

Fire to the Fields: The General Strike in Martinique

Although Guadeloupe’s sister island of Martinique had been spared the storm of 7 August 1899, it had not been spared the civil discontent that preceded it. Laborers’ frustrations continued to mount over the following months, and on 5 February 1900, agricultural workers on the sugar plantations of Saint-Jacques, Pain-de-Sucre, and Charpentier in the northeastern communes of Marigot and Trinité on Martinique threw down their tools and refused to work. A day later, workers on the other side of the island in Le Lamentin went on strike as well. Within a few days, workers were marching throughout the island asking that their compatriots cease their work in solidarity. What began as a highly localized demand for a wage increase extended to the sugar refineries along the coast, and as sugar production came to a grinding halt, the alarmed governor dispatched the colonial militia. Around four hundred workers congregated at the refinery near Le François on 8 February to voice their complaints, and a military detachment met them.109 When told to disperse, the strikers responded with Mirabeau’s revolutionary phrase, “We are here by the will of the people and we shall yield only to bayonets.”110 The soldiers opened fire and killed eight agricultural workers and wounded fourteen others. Over the next two weeks, the strike spread across the island, and as homes and plantations were set ablaze, rumors of insurrection erupted in the sensationalist U.S. press and stoked the fears of French conservatives.

Although the escalation of the strike prompted the French government to reinforce the garrison at Fort-de-France and to send several French cruisers to the island, the mainstream French press did not initially give the strike prominence.111 Newspapers in the nearby United States reported it in sensationalist fashion, in keeping with their reputation for yellow journalism established in the “Remember the Maine!” incident two years earlier that supported an imperialist U.S. agenda in the Caribbean. What the United States characterized as open rebellion akin to the Haitian Revolution that might open opportunities to obtain the strategically located Martinique for U.S. interests, the French papers covered as labor troubles incited by French socialists, American provocateurs, or gubernatorial incompetence. Though the shooting at Le François sparked outrage in the metropolitan socialist paper L’Aurore, which deemed it a “massacre” and declared the paper’s “sorrowful sympathy with the workers in Martinique” who were the “unfortunate victims of bourgeois capitalism and militarism [under the Marquis de Gallifet],” the general strike often emerged in the Parisian dailies under the rather bland heading: “The Troubles in Martinique.”112 But U.S. coverage threw fuel on the fire of downtrodden French workers staging their own strikes in the metropole, leading to a heated parliamentary debate over labor unrest in Martinique and the efficacy of the French government that lasted long after the strike ended in late February. Throughout the parliamentary sessions in 1900, “Martinique” became a buzzword those on the left and right mobilized as they fought for control of the French Chamber of Deputies.

While natural disasters and civil disorders share much with regard to emergency organization, preparedness, and authority response, the willfulness of civil disobedience creates a different social context that frames the event as an expression of the public’s volition rather than the results of an unforeseen eventuality. Throughout the event, French officials readily mapped their preexisting political tensions onto the events in Martinique, as they debated whether the individuals involved were to be treated as citizens who needed protection or criminals to be prosecuted—or, in the case of Le François, executed. The delineation between illegal civil disorder and legitimate civil disobedience was grounded in the same political and social prejudices of the left, right, and center that were applied to labor movements within metropolitan France.

Employing a French Precedent

On 7 February, delegates the striking workers at Sainte-Marie had chosen sent a letter articulating demands for an increase in salary and pay rate to the justice of the peace of Trinité. Though technically wage rates in Martinique were higher by 1900 than they had been in previous decades, workers were paid “by the piece.” As in Guadeloupe, the growth of beet sugar in Europe and the resulting worldwide overabundance of sugar subjected Martinique’s plantation economy to fluctuations that burdened workers with an unreliable pay rate based on production amounts. Though tariffs on beet and cane sugar set in 1892 and equalized in 1897 helped to mitigate the downturn in the Antillean economy, they also forced the Antilles into direct competition with mainland beet sugar and prevented trade with the United States. As agricultural workers suffered a worldwide crisis of overproduction, which resulted in the collapsing price of sugar in France, Martinique lost a quarter of its sugar factories by the close of the century, and real wages were a fraction of what they had been prior to 1884.113

Drawing on metropolitan legal precedents, Martiniquais workers demanded their salary increase in accordance with the Labor Law of 1892, which provided legal means for workers to arbitrate demands with their employers. This law, developed for mainland France, contained a caveat in article 16 that extended its application to the old colonies of Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Réunion.114 Though the explicit statement underlined the colonial status of these colonies, the extension of this metropolitan law nonetheless reflected their special status within the French empire in comparison with newer colonies. Asking for a salary increase in light of what the workers identified as a recovering sugar economy between 1897 and 1900, their letter directly invoked the civil rights outlined in the law of 1892, demanding “equality of treatment for all workers.”115

The workers’ letter marks the first invocation of the 1892 law in Martinique, and it couched the workers’ demands in markedly French terms. With the takeoff of the industrial sector in the latter half of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth, strikes and labor unrest came to characterize France and French politics. Between 1893 and 1903, nearly six thousand strikes and lockouts plagued metropolitan France, and about 10 percent were successfully resolved according to the provisions of the 1892 law.116 The Martiniquais workers were participating in a widespread French phenomenon: labor unrest and arbitration, both successful and unsuccessful.

Most of the plantations made a deal with the strikers on 13 February at Sainte-Marie: workers would receive a pay increase of 25 percent.117 Some workers found this compromise satisfactory; others saw it as a copout or even treason. On 14 February, a second arbitration at Rivière-Salée granted a wage increase of 50 percent, effectively bringing an end to the first general strike in Martinique. By 21 February, most of Martinique’s agricultural laborers had returned to work, and though bands of forty or fifty “agitators,” as the U.S. press described them, continued to harass workers on the island, most of the sugar refineries and plantations had returned to full operation.118 Although there were several more fires and demonstrations at the end of February around Trinité and in the southern plantations, events had calmed by early March.119

Debating the Strike of 1900

Although the general strike had ended, the controversy had not. Given that the workers themselves were drawing on precedents that were rather controversial in French politics, it is unsurprising that the February strike in Martinique quickly became bound up in contentious metropolitan politics. The socialists began to term the shooting at Le François the “Colonial Fourmies,” recalling the massacre of French workers in Nord in May 1891, which is widely regarded as a foundational moment of French socialism.120 Both the political left and the colonial ministry argued that Martinique’s deputies had failed to make good on promises to raise their constituents’ wages.121 The center-right, arguing that the strike was emblematic of electoral fraud, an issue plaguing metropolitan politics throughout the Third Republic, implicated the socialists. Approaching the issue as an administrative problem, the right took the occasion to discredit Waldeck-Rousseau’s coalition government and tried to retake the chamber. In other words, the strike fed mounting tensions between left, right, and center in French politics, and the only thing all sides agreed on was that the problems it represented—whether attributable to Waldeck-Rousseau’s ministry, Martinique’s governor, members of the chamber, or the electoral process—were an extension of those in metropolitan France.

As the issue entered the realm of French politics, disagreements over the cause and impact of the strike were legion. According to Guadeloupe’s socialists, the Martiniquais workers were unsatisfied with their deputies, Osman Duquesnay and Denis Guibert, because once taking office they had, in a reversal, sided with the more conservative elements of the French legislature. Likewise, colonial minister Albert Decrais and others in the chamber accused Deputy Guibert of having unwarrantedly promised wage increases as part of his electoral platform. Duquesnay and Guibert blamed Governor Gabrié for calling out the troops to achieve his own political motives.122 Guibert went so far as to accuse the governor of organizing an uprising designed to influence the local election, claiming that Gabrié delayed two days before responding to the situation in an attempt to strong-arm voters. He refused to call the strike a strike, claiming the government invented it as an excuse to cover up gubernatorial disorder and corruption.123

Similarly, having witnessed the peaceable negotiation of a wage increase in January by agricultural workers in the north, Duquesnay claimed that he saw the February strike coming and that he had tried to warn the colonial minister, M. Decrais, but no one heeded his warnings.124 Like Guibert, he argued that the workers were provoked into a riot, and as a result of the government’s mishandling of the situation, “French blood was spilled on French soil.”125 By 1900 Duquesnay sought more autonomy for Martinique and vociferously opposed assimilation into the metropole. Despite having been one of assimilation’s most vocal supporters just sixteen years earlier, he reached a rapprochement with the island’s powerful békés later in his political career. Consequently he appealed to conservatives’ “blood and soil” understanding of French identity when discussing the events at Le François, and his appeal to local autonomy and French identity resembled—in language as well as content—those made by traditionalists who championed the distinctiveness of the local pays within the metropole.

The constant allegations shrouded the strike in controversy, leading Guibert to publicly assert that the U.S. press was better informed than the French.126 Though the record does not support this assertion, he rightly identified scant and conflicted information in the French press. Operating on the official information wired to Paris by the governor, the French press initially reported that the troops at Le François had been attacked and thus implied that the use of force was warranted.127 The commander of the military detachment, Lieutenant Kahn, had claimed that since the “rioters” had attacked his troops, he was left with no option but to fire. However, it soon became clear that evidence did not support this story: the police chief present at Le François claimed the soldiers fired on the strikers without warning or provocation, three men died from bullets to the back, and most of the wounded and killed were found at least thirty meters from the soldiers.128 To address the conflicting reports from colonial officials, Waldeck-Rousseau announced that the state should conduct a formal investigation into the events at Le François, and that Édouard Picanon, inspector general of the colonies and lieutenant governor of French Cochin China, would conduct the investigation under the direction of the colonial ministry.

The heatedness of the debate precluded Decrais’s Colonial Ministry from having full discretion in handling the problem as a purely colonial matter. On 21 February, citing “the emotion produced in the hearts of Parliament by the current events in Martinique,” “the accusations leveled against the republican population of the island by its own representatives,” and “the maneuvers employed by a political party to deny the purely economic and social character of the agricultural strike,” the General Council of Martinique resolved to conduct its own examination into the social and economic situation which gave rise to the strike.129 By this resolution, local officials in the Council named the unrest a legitimate strike, declared the island’s inhabitants to be inherently republican, and expressed disapproval for the character attacks leveled against the workers. Martinique’s General Council was not willing to cede full authority to Decrais’s Colonial Ministry.

Likewise, the Chamber of Deputies followed Decrais’ every move, holding standard sessions in February and March, as well as a special session in December, to discuss Martinique’s general strike. During the March session when it was decided that the Colonial Ministry would investigate the strike, the socialists sent their own investigator, Guadeloupean deputy Hégésippe Jean Légitimus—whom many accused of having incited the unrest in Guadeloupe during the previous year—to Martinique to investigate the shooting at Le François.130 The special session in December was convened to evaluate the ministry’s handling of its investigation. Not only were many in the chamber dissatisfied with the ministry’s handling of the report, but some of the more radical members even claimed Decrais had falsified information.

From the outset, the ministry’s investigation was contentious and laden with political baggage from metropolitan struggles in the chamber. When Waldeck-Rousseau announced the investigation, he declared the need—to the boisterous applause of the left and protestations from the right—to give “to the population of our colony the impression that, there like elsewhere, we mean to enforce, at the same time, order and liberty.” In response, Deputy Lasies from the right exclaimed, “What a nice phrase! You treat us worse than the negroes!”131 As labor, politics, and race were superimposed on one another, French legislators fell into distinct camps: those who viewed the workers’ actions as part of a riotous uprising and those who saw them as part of an organized struggle for economic equality. Despite the blatant racism exhibited by deputies like Lasies, the problems brought to light were, in many ways, endemic to metropolitan France: as the push for social justice gained ground at the close of the nineteenth century, many on the left condemned the right for the plight of all workers, and many on the right considered all collective action to be unwarranted, riotous behavior. As a moderate coalition, Waldeck-Rousseau’s ministry was stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Remember Martinique, Remember Chalon!

During the meeting of 14 February, the Socialist Party of France proclaimed, “The Committee general of the French Socialist Party affirms the sympathy which links it with the workers of everywhere without distinction of sex, race and color. It declares itself to be in solidarity with the working victims of Martinique and denounces with public indignation the new crimes of the capitalist middle-class and militarism.”132 In stark contrast to the claims from the right, socialists held that the agricultural workers had been calm and moderate in their demonstrations during the strike. Despite the factory and plantation owners’ attempts to incite the workers and thereby justify the type of repressive action witnessed at Le François, the workers by and large maintained a cool and collected demeanor.133 Parliamentary debates reflected this sentiment: socialists opened their ears to Gerville-Réache, who did not believe that strikers set the fires, accusing “criminals”—that is, the plantation owners—of setting the fires to attract military intervention.134 His accusations resonated with those made against the békés during Guadeloupe’s unrest, and consequently his politics earned him no fans among the “order and liberty” crowd; during his years as deputy, the Parisian police maintained an extensive dossier on him.

On the twenty-ninth anniversary of the “Bloody Week” in May 1871 that brutally repressed the Paris Commune, demonstrations were held across Paris. According to newspaper reports, somewhere between twelve thousand and twenty-five thousand people took to the streets and marched through the Père-Lachaise cemetery. As the socialists marched shouting “Long live the Commune,” they waved red banners that read “To the victims of Galliffet! To the victims in Martinique!”135 Gaston de Galliffet was one of the generals who had led the attack against the communards, and he was the minister of war under Waldeck-Rousseau until his resignation two days after this demonstration. In remembering the communards, therefore, protesters drew a straight line from the bloody foundational moment of the Third Republic to the repression of the strikers at Le François—evidencing the integration of Martinique into the socialists’ narrative of French history.

Socialists therefore conjoined metropolitan labor troubles with those in Martinique. Shortly after the general strike in Martinique, a strike broke out in early June at an ironworks in Chalon-sur-Saône. Police confronted over one thousand workers, and after a heated exchange the police opened fire on the crowd, killing one striker and seriously wounding twenty others.136 Throughout the socialist congress held from the twenty-eighth to the twenty-ninth of September, party members cursed the bourgeois class for exploiting the French proletariat in incidences of strike repression, repeatedly uttering “Martinique” and “Chalon” in the same breath. For instance, as one citizen was criticizing the Waldeck-Rousseau cabinet as overtly bourgeois during the second day of the meeting, those in attendance took up the cry “Les massacres de Chalon et de la Martinique! Massacreurs!”137

The socialist congress met in Lyon the following year. Faced with what they called the greatest crime against the working class since the Paris Commune, members present at the Third Socialist Congress in May 1901 issued a manifesto to the workers of Martinique in which they proclaimed, “Your enemies are our enemies. . . . Count on us as we count on you. Long live socialist Martinique! Long live the social Republic!”138 The socialist journal Le mouvement socialiste also highlighted the bond of common class struggle: “What happened here shows that the proletariat of the Antilles—with its strikes and organizational tendencies (unfortunately blocked by exterior causes thus far)—already entered into the conscious phase of class struggle. It disciplines itself more and more in this form of activity that makes the working class the great factor of transformations to come.”139 For French socialists, the strike marked Martinique’s rite of passage into full working-class consciousness.

Fears of the Right

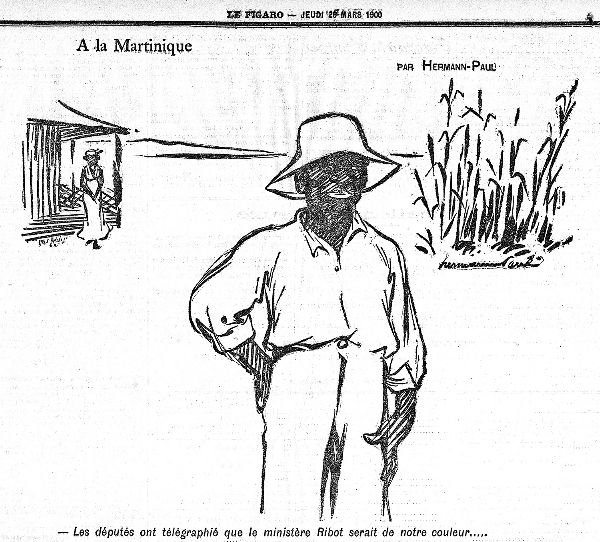

Although the more liberal republicans and socialists were willing to treat the strike in Martinique inherently as a labor issue, the conservative press treated the strike as a matter of “the black question” and foreign interference. As was evident during the Pointe-à-Pitre fire in 1899, officials in France worried about a rising anarchosocialism among the island’s black population, while the sensationalist U.S. press issued a warning against allowing “rioting blacks” to go unchecked.140 Witnessing the political agitation of a predominantly black population, the conservative press was quick to label the worker action as riotous at best and rebellious at worst. For instance, the bimonthly review Questions diplomatiques et coloniales readily viewed the strike as a black insurrection: “In the course of a strike with as of yet undetermined causes and importance, a part of the indigenous population, those employed in agricultural work, entered into insurrection.”141 The conservative interpretation of the event—evident in the Chamber of Deputies and particularly prevalent in the U.S. press—asserted that the labor unrest was the result of granting black citizens the right to vote in 1848.142

A conservative article for the magazine L’Illustration focused on the “black question” in a similar fashion, insisting that the strikers were indeed rioters who forced hardworking men to stop their work on the threat of death; plantation owners in Guadeloupe had made similar accusations against black laborers with regard to indentured servants. Seeking to validate the actions of Lieutenant Kahn, the author claimed that the riotous black workers menaced the white population the day after the incident at Le François, burning plantations and crying out “Down with the whites! Long live the negroes! Vengeance!”143 Le Figaro echoed this fear of the black masses.144 Overall, the conservative press treated the shooting at Le François as a hard lesson to brigands and rioters.145

Though much of the rhetoric surrounding the strike was overtly racist in nature—and intricately tied to a history of chattel slavery—it also represented the right’s growing fears of internal contaminates in French society, typified by the political struggle between the dreyfusards and anti-dreyfusards.146 When Lieutenant Kahn was pulled from active duty following the Picanon investigation, the monarchist newspaper Le Gaulois reported that “the disgrace of M. Kahn—a new victim of the dreyfusards, and a Jewish victim, this time—is a token paid to the socialists who had threatened to vote against the current cabinet in mass until the return of the investigation into the affair of Martinique.”147 The fear was not merely that colonial subjects were revolting against their colonial government, a situation that military strength would rectify, but that members of French society who, like Dreyfus and his advocates, simply did not belong, or who, like the socialists, would undermine French society. With regard to the “old colonies,” where nonwhites held the legal status of citizens and not subjects, the “black question” resonated with the right’s fears over foreign “contagions” within France’s civil society that threatened their mythic “blood and soil” image of France.

The right’s fears also had an international dimension. The U.S. press unambiguously sided with Lieutenant Kahn, consistently reporting that his troops had been attacked and were merely defending themselves.148 U.S. journalists warned that Martinique would follow in Haiti’s footsteps by constantly proving that it could not handle the freedom slaves had won.149 Frustrated by what it saw as the French downplaying the situation, the New York Times asserted that while “nothing short of a rebellion is in progress there, due to maladministration, . . . the official reports attribute the trouble entirely to labor agitation, and take the most hopeful view of prospects for an early settlement of the trouble.”150 The French press seized on this sensationalism and accused the United States of jealously eyeing Martinique, attempting to use racial unrest to foment a rebellion in order to seize it.151 In fact the United States had been actively asserting its own dominance in Caribbean affairs since the Monroe Doctrine eighty years earlier, and had recently seized Cuba and Puerto Rico during the 1898 Spanish-American War.