CHAPTER 7.

Korea to Vietnam

The sniper’s task is to kill individual enemy with single rifle shots very quickly aimed if necessary. He will never fire a rapid succession of shots, except in self-defence. As a guide, the standard of shooting to be demanded of a sniper will enable him to hit, with regularity, a man’s head up to 200 yards, and a man’s trunk up to 400 yards, though this standard may well be surpassed.

British Army Training Pamphlet on Sniping, 1946

Post-war reorganisation of the Australian Army

The Australian Army began demobilisation even before the end of the Second World War, with around 100,000 soldiers released to support industry and agriculture in the last two years of the war. Understandably, both the Curtin and Chifley governments turned their attention from defence to post-war reconstruction. The reorganisation of the Army in 1947 allowed for a regular force of around 19,000 based on a brigade group and a volunteer militia of 50,000. This eventually led to the creation of the Royal Australian Regiment (RAR), consisting of three regular infantry battalions, in 1948. However full employment and poor military rates of pay and conditions of service meant that the regular infantry battalions were at less than half-strength by the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950. It was partly for this reason that a national service scheme was introduced in March 1951, with all eligible males required to render a period of continuous full-time service in the Citizen Air Force, Citizen Naval Forces or Citizen Military Forces (Army). Due to the need for manpower, most of the national servicemen saw service in the CMF.

When the Korean War broke out in June 1950, none of Australia’s three regular infantry battalions was anywhere near combat ready. They were undermanned, undertrained, still equipped from Second World War inventories and organised for jungle warfare rather than the type of battlefields they would be exposed to in Korea. By the end of June 1950, the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR), then serving with the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces (BCOF) in Japan, was preparing to return to Australia and had reduced its staff to the point that it was 11 officers and 134 other ranks short of normal establishment, and over 400 short of its war establishment. Due to its BCOF commitments, it could only engage in very limited training. Notwithstanding these shortfalls, by the end of the following month, 3 RAR began to prepare for possible deployment to Korea and commenced a period of intense training to prepare for combat operations, while being simultaneously re-equipped and reinforced by a special recruiting campaign to bring it up to war establishment.

Australian sniper rifle in Korea

Short Magazine Lee-Enfield (SMLE) No.1 Mk.III* (HT)

The Australian SMLE Mk. III* (HT) sniper rifle with a locally made version of an Aldis Pattern 1918 telescopic sight (AWM REL37030.001).

With the outbreak of the Second World War the Australian Army searched for a viable sniper rifle to supplement the small number of P14 sniper variants they already had in store. With a large stockpile of the SMLE No. 1 Mk. III*, the Commonwealth Small Arms Factory at Lithgow had little option but to experiment with the SMLE.

The result was the fitting of a Lithgow-manufactured heavy target barrel with an Aldis Pattern 1918 three-power scope, also known as the Straight Telescopic Sight Pattern 1918. The mounting of the scope was a virtual copy of the German system which had been successfully used in the First World War. Production delays meant that it was not available until almost the end of the war, with only a few reaching the Pacific theatre. Up to that time, Australian sniping was almost exclusively conducted with the Enfield No. 3 Mk. I* (Pattern 1914) sniper rifle, the standard or heavy barrel SMLE and various American rifles.

The new sniper rifle was designated the SMLE No. 1 Mk. III* (HT), the ‘H’ standing for heavy barrel and the ‘T’ for telescope. It was a reasonable compromise and a fairly accurate weapon, but far from perfect. Over 1600 of these dedicated sniper rifles were produced, with many seeing service in Korea. A number were pressed back into service in 1976 with the re-introduction of formal sniper training at the Australian Army Infantry Centre. They were eventually replaced by the commercially available Parker Hale M82 sniper rifle in the late 1970s, also a stop-gap measure, while the search for a dedicated solution to the modern needs of the sniper continued.

The Korean War (1950–53)

The war establishment for an infantry battalion at the time included a sniper section under the command of the battalion intelligence officer. The sniper section consisted of one sergeant, one corporal and six private soldiers, or four sniping pairs, with the 3 RAR snipers identified from the best available shots in the unit and from the reinforcements. As the battalion was more than 300 men under war establishment by the end of August 1950, the commanding officer must have placed some importance on his sniper section as, by the time the battalion commenced its pre-deployment exercise, Exercise Experimental, it had reached full strength. From the available records, these men were Sergeant Thorogood (killed in action 15 February 1951), Corporal Stark (wounded in action October 1950) and Privates Robertson, Gully, Adams, Alberts, Bellchambers and Hutton. All were qualified marksmen, with Robertson and Stark taking out 1st and 2nd place respectively in the 1952 final elimination shoot of the British Commonwealth Forces, Korea, Queen’s Medal — a prestigious rifle-shooting competition.

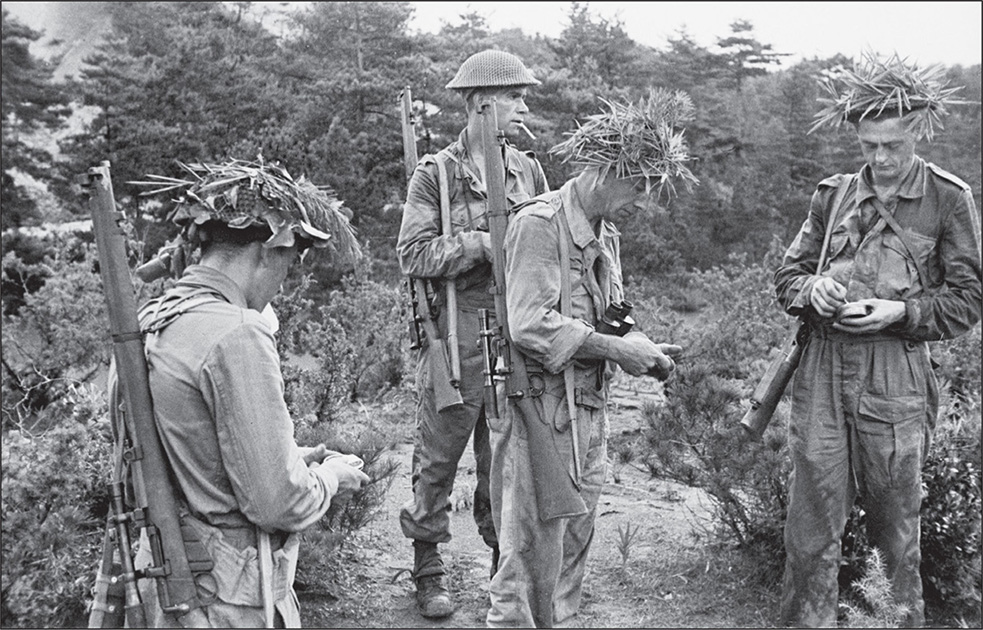

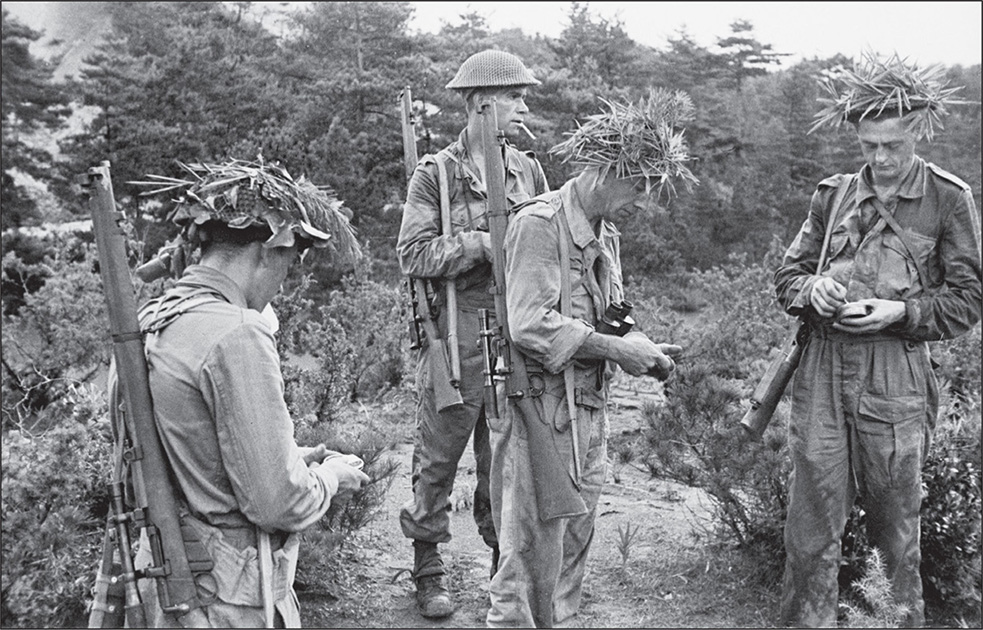

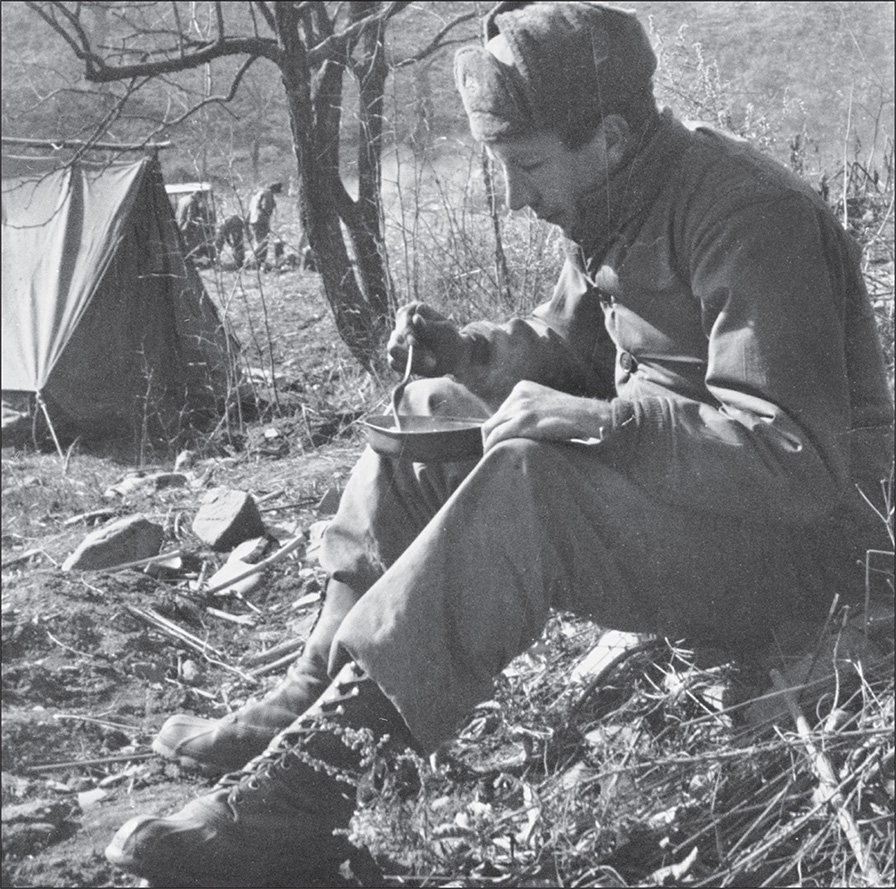

3 RAR soldiers training in Japan in August 1950. Identified soldiers are, left to right: Privates Hutton, Alberts (with cigarette in mouth), Gully and Bellchambers. A fifth sniper, Private Robertson, who was also the battalion’s photographer, is taking the picture. Note that the soldiers’ rifles are all SMLE Mk. III* (HT) (AWM P01813.326).

The 3 RAR sniper section was under the command of the unit’s intelligence officer, Lieutenant Alfred ‘Alf’ Argent; however, there was little information available to him to assist in the training and preparation of his snipers. The military art of sniping had been neglected after 1945 and there was no sniper concept of operations or approved sniper training program, and the only doctrine or training documents available were British pamphlets from the First and Second World Wars. While there were some ‘old hands’ in the battalion who had worked with snipers in the Pacific during the Second World War, jungle sniping experience was of little value in preparing the men for sniping in what was expected to be a fast-moving and rapid war across vast, open tracts of land. In 3 RAR, sniper training only commenced in earnest on 27 August 1950, and was conducted at a very basic level. Fortunately, the eight new members of the sniper section were both keen and proven marksmen, although they had no idea what was required of a sniper in Korea. Initially they focussed on learning all they could about their new sniper rifle, the SMLE Mk. III* (HT), which had only been introduced into service in the closing months of the Second World War. The rest they had to learn ‘on the job’.

By the time 3 RAR arrived in Korea in late September the snipers had paired off. Sniper Sergeant Jim Thorogood, who had served in the Pacific campaign, wanted the younger snipers paired with older hands, preferably men with combat experience from the Second World War. He realised the dangers of an overly keen sniper who might prefer to shoot rather than sit still in a hide for hours at a time. Private ‘Robbie’ Robertson was paired with Private Lance Gully, who had served in the Pacific. Gully and Robertson had formed their sniping partnership during basic training in Japan and had become close friends. Both were excellent shots and would take turns being the sniper while the other acted as observer. Almost immediately on their arrival in Korea the battalion was launched into the thick of the fighting as the formation to which they were attached, the British 27th Brigade, later designated the Commonwealth Brigade, pursued the retreating Korean People’s Army. In October, when the Chinese entered the war, 3 RAR was often required to conduct a fighting withdrawal while covering the withdrawal of other Allied formations.

The sniper war in Korea was vastly different to the Australian sniper’s experience in the Second World War where the jungle usually restricted sniping to snap shooting over short distances, often without the use of a telescopic sight. In Korea the snipers could, theoretically, target out to distances of 1000 yards (914 metres), the maximum elevation on the Pattern 1918 scope attached to their sniper rifle. In practice, it was very rare for a sniper to attempt to hit a target at this distance. Between 200 and 400 yards (183–366 metres) was considered the ideal targeting distance, particularly for novice snipers. The cold, dry, windy and often high altitude of the fighting in Korea had a significant effect on the ballistics of their sniper rifles to which they took time to adjust. The openness of the battlefield, particularly when the conflict bogged down into static warfare, also highlighted the importance of camouflage, the use of hides and restricting movement in daylight, and shooting in hilly or mountainous terrain, which made judging distance difficult. The extreme cold in winter seized the adjusters on their scopes and forced them to sleep with their weapons to stop them freezing up. Frostbite was also a constant risk to the sniper who had to remain hidden and still for hours in the frozen terrain. There were some unusual and unexpected challenges, such as the size of the trigger guard on the SMLE which was too small to take a thickly gloved finger, risking frostbite when the finger was uncovered. Kevin Tupper, a sniper with 2 RAR, recalled that, while he considered himself ‘a crack shot at home’, he found that it took him some weeks to adjust to the Korean environment, ‘not to mention some bugger trying to kill me’.

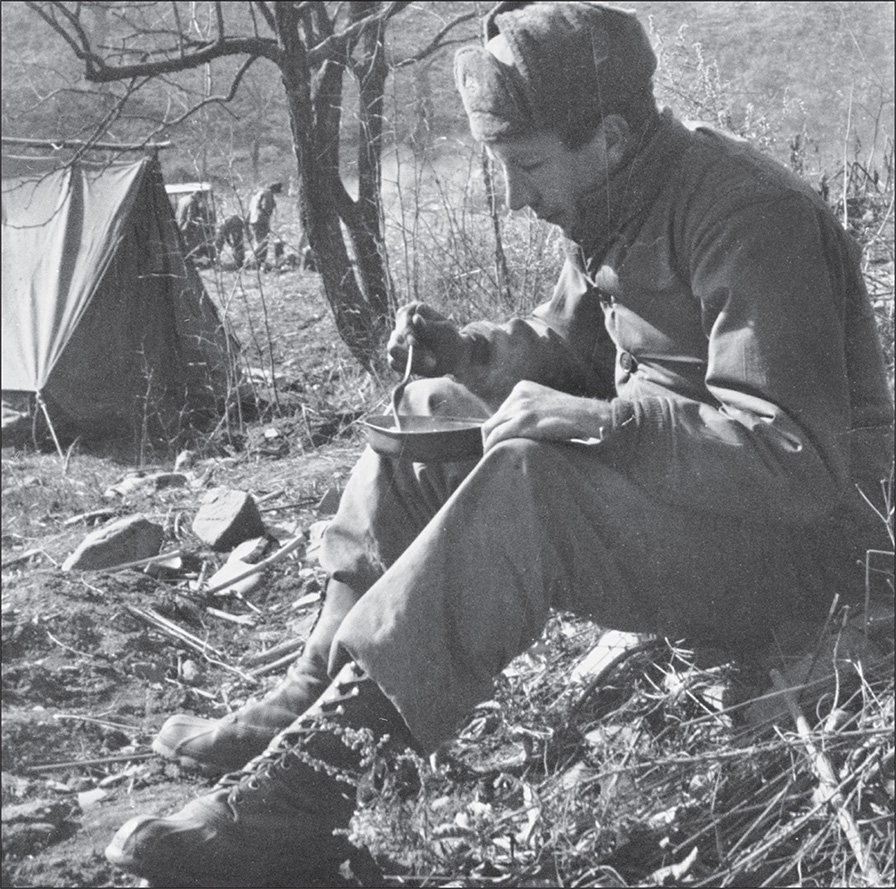

Private Lance Gully, a sniper with 3 RAR in Korea in 1950. Gully was wounded several times in a savage exchange of fire with the enemy shortly after this photo was taken (AWM P01813.473).

Around a month after their arrival in Korea, Robbie Robertson and Lance Gully were tasked with providing a protection detail for the battalion’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Green. According to the battalion intelligence officer, Lieutenant Argent, the commanding officer liked to keep ‘well forward, in fact immediately behind the leading infantry company group’. On this day, the commanding officer’s party had just arrived at an apple orchard near the town of Yonju. While Lieutenant Colonel Green gave his orders to his company commanders for a planned attack, both Gully and Robertson reconnoitred the immediate area, with Gully moving to inspect what appeared to be an irrigation ditch. Robertson suddenly ‘heard rifle shots and a flurry of grenades bursting’. The ‘irrigation ditch’ held a section of North Koreans who threw grenades at Gully as soon as he came within range. Without thinking, and in order to dodge the grenades, Gully jumped into the ditch firing from the hip. As Robertson ran towards the commotion he saw Gully ‘staggering out [of the ditch] with seven holes in him and a big flap of scalp sticking up’. As Robertson approached, Gully said breathlessly, ‘there’s a million of them in there, and they’re all yours’. Robertson dropped to the ground above the irrigation ditch and worked his way along it. He described what happened next:

I did what an old soldier had told me … The first time you see the enemy, [and] the butt of your rifle is hard against your shoulder, he’s dead before he knows it … Keep attacking and keep them off balance, and whatever you do, count the rounds. I started off with 11 rounds, and would fire until I had four rounds left and then I would insert another clip of five. Five will go in on top of four quite smoothly, but with five on top of five, the last round is hard to push into the magazine … A hard grip with both hands, take up the first trigger pressure, deliver the shot with both eyes open so you have a wide-angle view of the battlefield in front of you, keep knocking them down, move fast. You keep the pressure on them, keep attacking, then skip back and shove five rounds in, then fly back in again. That’s exactly what I did, and it worked. The whole ditch was cleaned out.

Although seriously wounded, Gully had killed or wounded nine of the enemy and within minutes Robertson had finished them off. No sooner had the action at the irrigation ditch ended when an enemy officer, armed with a Soviet PPSh 41 7.62mm sub-machine gun,

came boring out of the bunker and hosed me down with his burp gun … I fired a shot at him as I went to ground, but I missed. … one round hit me, slashing across my wrist, before I could [reload] … Then I started to run at him and I killed him. He was absolutely unlucky that bloke. A real good, hard-fighting soldier.

The Soviet PPSh 41 ‘Burb gun’ (Wikipedia Commons image).

After Lance Gully recovered from his wounds and returned to 3 RAR, he thanked Robertson for his advice just before the firefight. Robertson recounted the conversation:

Lance asked how many rounds I had loaded. I said I had one round in the breech, and another ten in the magazine. He said ‘Why eleven?’ and I joked and said I might meet eleven of the enemy. He said ‘I only carry five in mine, I don’t want to weaken the magazine spring’. I said for God’s sake Lance, put another five in, the enemy are just up here and we could be in a fire fight in a minute. … Had he not put that extra five rounds in he would have gone. That’s how it works; survival in battle is based on skills and luck, and some of the luck you make yourself.

Lance Gully’s replacement in the sniper section was Private Bill Hall. Hall was a self-confessed ‘smart arse’: ‘I thought I knew all that there was to know at just 20. But few of us were real experts at war in Korea.’ During the Battle of Kapyong in April 1951, Hall and his intelligence sergeant at the time, Sergeant Col McGregor, were tasked with protecting 3 RAR’s battalion headquarters:

By the time of the battle we hadn’t had any sleep for a couple of days. We positioned ourselves on a small hill overlooking the battalion CP [Command Post] so we could get a good view and cover the HQ by fire. The Chinese got right in close to our HQ and there was small arms fire everywhere. Every bugger in the HQ had to fight as we had nowhere to go and no vehicles to get there. Our Regimental Police section lost a few men, as did the signallers. Our comms was gone and we had to rely on runners. In the dark I’ve got no idea if I hit anyone, but it was a close run thing. The following day, after the battalion had withdrawn, the RSM asked me to escort the padre, Padre Lang, to the battlefield looking for our dead and missing. That was an unnerving experience. I did a lot of escort work as a battalion sniper.

Apart from their sniper rifle, snipers in Korea also typically carried 300 rounds of ammunition; a compass; binoculars or Scout Regiment Telescope; leather case for the rifle’s scope, if it was not kept on the weapon; notebook, pencil and watch; groundsheet and up to two days’ rations if operating from a hide or on patrol. Some also carried a sidearm, usually an American Colt .45 calibre, an entrenching tool (a small collapsible shovel) to help dig through the snow when establishing a hide, and a face veil. Occasionally the sniper’s observer would carry an Owen gun when on patrol. Bill Hall procured a Garand M1 rifle from the Americans which he often used in preference to the Australian SMLE. Camouflage suits were very rare in Korea, particularly as the war became static, with most snipers preferring to use local vegetation when operating out in the open.

An SMLE Mk. III* (HT) sniper rifle and standard auxiliary equipment. The brown leather container was for the Scout Regimental Telescope normally used by the observer, with the grey-green canvas-covered cylinder used to house the Pattern 1918 sniper telescope when not mounted on the rifle. The ammunition bandolier usually carried 50 rounds (image courtesy of Peter Bruem).

The sniper’s life was rarely comfortable. Robertson described a typical night:

Every night we’d have to dig through 18 inches [45 centimetres] of ice to reach unfrozen earth to sleep in. … [We slept with our] rifles to stop the metal freezing. If the barrel froze, fingers would stick to it … Laying up in hides [was] a problem - frozen stiff - low circulation danger. Fingers cracked, knuckles skin infected, knees bruised and aching from slipping in icy slopes. Breath freezing on upper lip, chilblains, nose chapped and raw.

Later in 1951, as the war became static and more characteristic of trench warfare, snipers had both the boring and repetitive routine of manning static observation posts and the hectic and sometimes terrifying experience of patrolling no man’s land. As snipers were supposed to be trained observers and were issued with telescopes and binoculars, they were regularly used to man listening posts and other forward outposts. Private ‘Frenchy’ Ray, a sniper in 2 RAR in 1953, explained that, while operating in an observation post, they ‘did 18 hours straight in pairs. Each individual sniper got a night off every 4th afternoon, to have a hot meal, bath, clean clothes and a sleep. It was pretty bloody boring.’

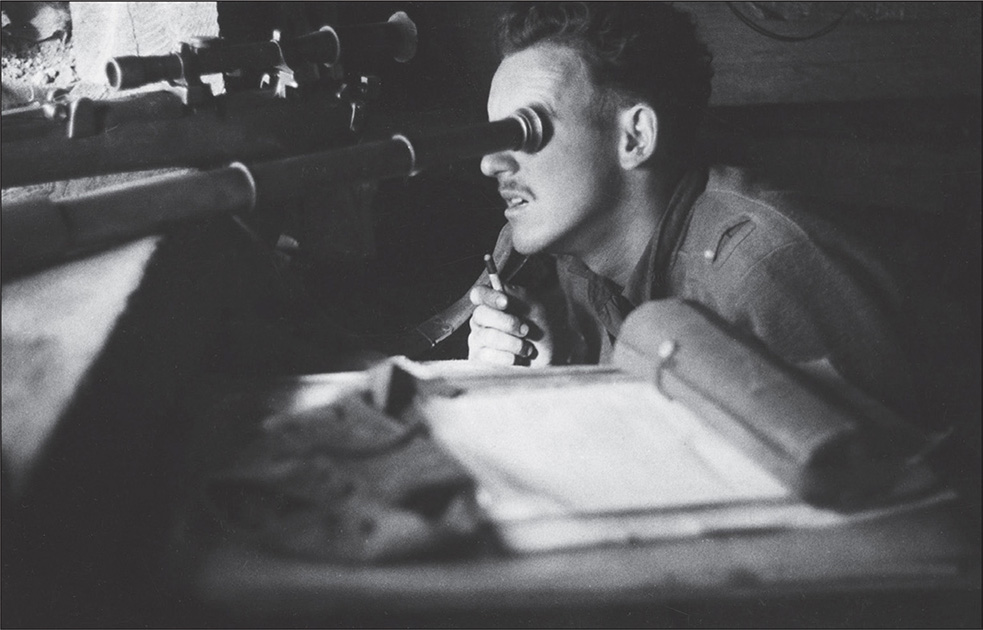

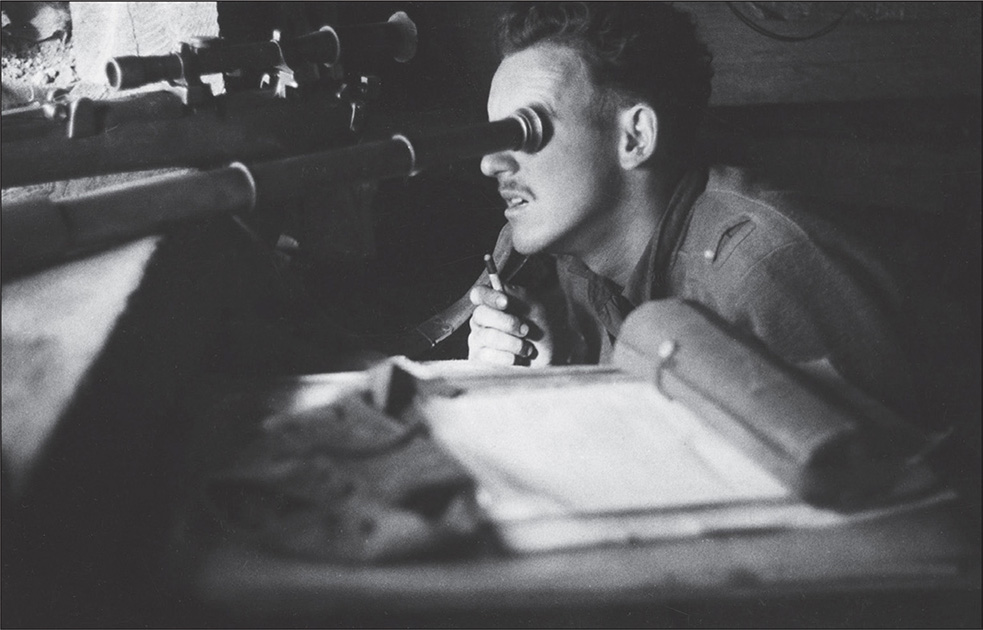

An unidentified sniper/observer at a sniper observation post in Korea in 1953. He has his SMLE No 1. Mk. III* (HT) sniper rifle at hand while he peers through a Scout Regiment Telescope (AWM 030517/02).

During the mobile phase of the war, the snipers would often be detached in direct support of the infantry companies. Because there were four infantry companies and only one sniper section, Robertson explained that,

during a big attack the companies would move through each other to attack a subsequent objective. It meant that while the men in each of the companies would maybe do only one attack in a day, we would have to support all of the companies and might end up doing three separate attacks.

With the advent of the ‘static war’, the Australians maintained an aggressive patrolling schedule with the aim of ‘owning no man’s land’. Snipers Kevin Tupper and ‘Frenchy’ Ray recalled that they were routinely called on to support patrols, ‘often being tasked with the most dangerous job of forward scouts’. Ray added that, while he did not mind supporting the companies, he did object to always getting the ‘crap jobs’ from them: ‘we were forever supporting the companies and, because we weren’t part of the company, we’d often get lumbered with all sorts of odd jobs, such as bogy guards, stretcher duties, [and] map attendants in the coy CP [command post].’

Occasionally the snipers were also tasked with other odd jobs such as trying to work out how to use a 60 mm mortar that had been left for one of the battalion’s companies without any instructions, or a Boys anti-tank rifle that had been converted to a ‘heavy sniper rifle’ by replacing its barrel with a Browning .50 inch and attaching a telescopic sight. The use of large-calibre rifles as sniper weapons was not unique. Large-bore hunting rifles were commonly used in the First World War and Australians had used the .50 calibre Boys anti-tank rifle to snipe at both the Japanese and Germans in the Second World War. However the United States took this idea further in Korea, fitting telescopes to Boys anti-tank rifles and Browning M2 .50 calibre machine-guns that had been rigged to fire on single shot. This was pioneered by an American Army ordnance officer, Captain William S. Brophy, who discovered that, in the mountainous terrain and at the high altitudes of Korea, the .50 calibre round travelled much further and with greater accuracy than the standard rifle calibres of the day. On another occasion the battalion snipers were tasked with working out how to employ a new sniper scope. Ray explained that,

On arrival in Korea in March 1953, the commanding officer addressed his snipers and told them that he saw them as the ‘eyes and ears of the battalion’, and that they had just purchased … an infra-red operated rifle called a sniper scope. It was excellent for picking out targets at night. The infra-red projector and sight was connected to a small automatic carbine [an American M1 carbine]. The whole thing was connected to a car battery which was carried in a canvas back pack. The system didn’t come with any ammo, so our first task was to ‘borrow’ some from a neighbouring Yank unit. The equipment was very heavy, but was effective out to 100 yds.

One of the particular dangers of the job was counter-sniping. While the threat from enemy snipers was not as significant as it had been against either the German or Japanese armies in past wars, sniping by Chinese and North Korean troops was a constant hazard, particularly for the Australian snipers whose job it was to locate and kill them. During action around Hill 614 in March 1951, 3 RAR was under sniper fire from the hills overlooking its positions. No-one was sure whether these were trained snipers or normal infantry, but there were rumours at the time that Soviet snipers were involved. While this was unlikely, the Australians had captured Russian Mosin Nagant M1891/30 sniper rifles used by Chinese troops, and there were a number of competent Chinese snipers, such as Zhang Taofang, who allegedly killed over 200 Allied soldiers in Korea.

North Korea’s Sniper Rifle —

the Russian Mosin Nagant M1891/30

The Russian Mosin Nagant sniper rifle (AHU image).

The Model 1891/30 sniper rifle was based on the standard Russian infantry rifle used extensively in the Second World War. Sniper variants were created from weapons that proved particularly accurate during production testing. During their conversion to a sniper rifle, they were fitted with either a PV (4x) or PU (3.5x) telescopic sight, the trigger was lightened to 4.4–5.3 lbs (2–2.4 kilograms) and the bolt handle was turned down for operation while using a scope.

As with the rifle’s peers in the Second World War, such as the sniper variants of the Mauser K98k and the Lee Enfield No. 4 T, the Model 1891/30 sniper rifle was reliable, rugged and accurate. While it was reportedly well-liked by its operators, it was longer and heavier than its German or British equivalents.

Around 330,000 of the sniper variant of the Model 1891/30 were produced between 1941 and 1943. After the war, the Soviet Union provided a number of these rifles for Communist nations and groups such as China, North Korea and the NVA in Vietnam.

Private Best, a sniper with 3 RAR, poses with the new sniper scope for a publicity photo in Korea in April 1952. While the device provided effective night vision, it was heavy, unwieldy to carry and awkward to use, particularly on patrol (AWM 147851).

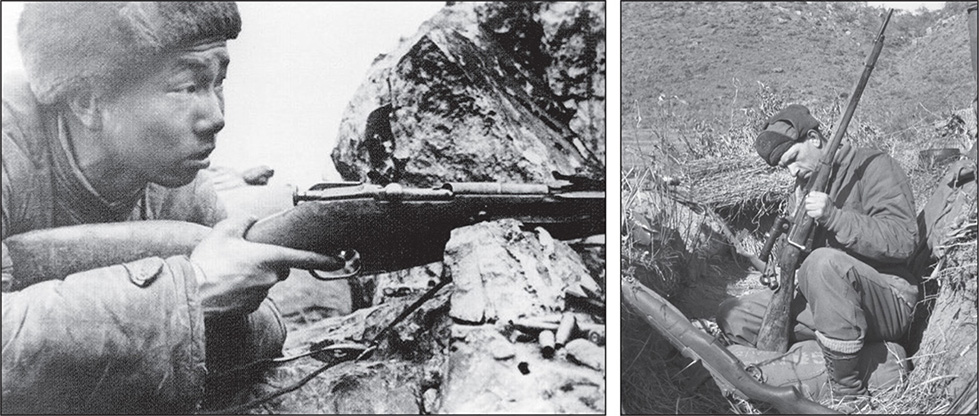

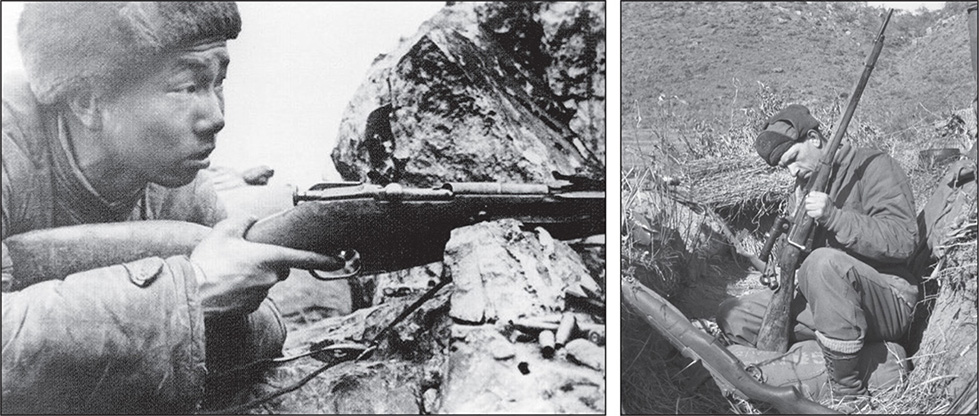

One of China’s best known snipers in Korea, Zhang Taofang, who was reportedly operated in the vicinity of the Australians in March 1951; and (right) Corporal ‘Stewie’ Ham, a sniper with 3 RAR, inspects a captured Russian 7.62 mm Mosin Nagant M1891/30 sniper rifle (AHU image; AWM P01813.474).

Notwithstanding reports of Russian and highly trained Chinese snipers operating in their area, most of the ‘sniping’ encountered by the Australians came from normal infantry using open iron sights. In July 1953 at the Battle of the Hook (also referred to as Battle of Samichon River), 2 RAR snipers Frenchy Ray and Kevin Tupper were deployed to a forward observation post. Ray and Tupper’s observation post had numerous rotting Chinese dead to its front:

The smell of rotten corpses was unbearable at first. We were just 200-300 yds from the Chinese trenches. The head of a freshly decapitated Chinese was starring [sic] at us through the opening [of our OP]. It was approximately 3 feet away, eyeball to eyeball. But from a sniper’s point of view we were happy. Were we truly sniping … eliminating their snipers. … [who] were a real pest. Couldn’t hit anything … Their main job seemed to be to draw our fire. On one occasion, this bloke suddenly jumped up in his trench, large as life, and started firing from the hip with an automatic weapon. My mate Frenchy had an old collapsible telescope, like the ones they used on old sailing ships. Anyway, he falls on his arse but I get off a shot and got him cleanly, then ducked.

Ray and Tupper maintained their vigilance against Chinese snipers, working out a routine. Having identified where all the enemy’s favourite sniper positions were, they marked them on their range card, numbered them from left to right, then zeroed in on each position. They also arranged for the night patrols to tie rags to the wire in no man’s land to assist them in estimating wind speed and direction. Once the spotter located an enemy sniper, ‘I’d shout out “Four!” Kevin would then alter his rifle position just slightly until his aim was on the spot “Four” and fire almost immediately, regardless if he could see a man or not. … We only had a split second to aim and shoot.’ The Chinese had their own plan to deal with Tupper and Ray: ‘They [the Chinese] also worked in teams where one would fire at us to get us to look through our loop hole, and the other would immediately blaze away with an automatic weapon at our sniper plate. … The first time they tried this the Chinese sniper was either a poor shot or over-excited as he stood up to fire, giving Kevin a good shot, and Kevin did not miss.’

While the Standard Operating Procedures stated that snipers were to work in pairs to maximise both effectiveness and protection, some men still preferred to operate as a ‘lone wolf’. Ray described one of his lone wolf operations on 12 May 1954:

At the crack of dawn I left for no-man’s land with my faithful .303 rifle. I advised the forward platoon of my time of return and marched down the hill. It’s the time of day when ambushes are unlikely. One can see fairly clearly ahead in the early morning light. The area had been shelled so often that no trees could be seen, just a few sparse bushes covered the countryside. I organised myself for a day of sniping, laying under some bushes. After some hours of looking around I heard a rifle being fired some 200 yards in the west-front of me. My heart started to beat. At last I was close to a Chinese sniper. I kept on looking for a long time but spotted nothing. This time when the Chinese fired his rifle once more, I saw a tiny puff of smoke filtering through a bush. I knew now where he was hiding but still could not see him through my telescope. I waited a fairly long time just watching the bush when I heard another crack of the rifle I lined up my rifle, nice and steady as if on the rifle range, and fired a single shot. Nothing happened, nothing moved. I waited another half hour and fired another shot. Still no move from the enemy. I passed the rest of the day waiting for his next move. Nothing. I had only two options, I had either killed him or scared the daylight out of him. I was bursting for a smoke by this stage of the day, so I chewed a Camel cigarette from my C ration pack.

Ray eventually returned to his lines, but not before being fired on by his own troops.

In October 1951, the Australian government bolstered Australia’s commitment to the war by sending a second battalion. However, finding sufficient snipers to support the two battalions proved difficult. Consequently, both battalions were forced to reduce the number of snipers to one sergeant and four privates, although there was no improvement in the level of pre-deployment training. In 2 RAR, for example, only one of the snipers had received any sniper-specific training before arriving in Korea, and this was ‘very basic’. Another had only fired five shots from his sniper rifle before departing Australia, and yet another had received no sniper training whatsoever and fired his sniper rifle for the first time after his arrival in the combat zone. This level of sniper training and awareness was reminiscent of the opening days of the Second World War and was unforgivable. The first batch of snipers in 3 RAR had learnt valuable lessons in their first tour, and these should have been built into the training program for the other battalions. Passing on combat experience to new arrivals is vital. For the sniper it could have meant the difference between life and death.

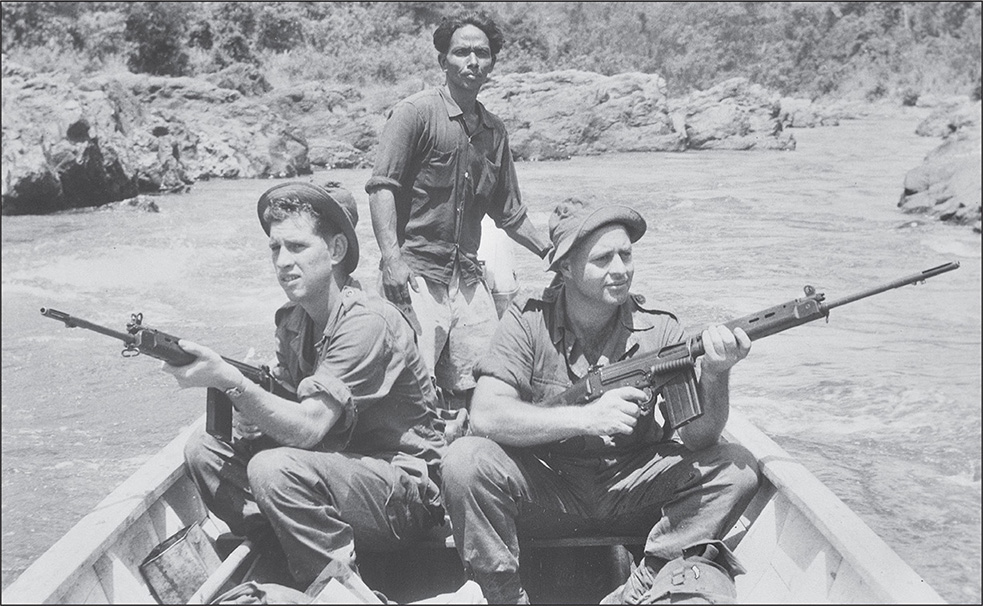

2 RAR sniper team in Korea in 1953 (top), and during their 50th anniversary reunion in Canberra in 2003.

Left to right: Kevin Tupper, Ray Godwin, Ed McMahon and ‘Frenchy’ Ray (images courtesy of Cyril ‘Frenchy’ Ray).

Kevin Tupper, who joined the Army in 1951 when he was just 16 having lied about his age, was a country boy and a good shot. As a lad he would lie on his back and shoot crows with his .22 calibre rifle. It was his marksmanship and hunting experience that helped him survive his first few months in Korea — it certainly was not his Army sniper training. ‘I was given no training on my weapon or as a sniper. The sergeant just gave us a sniper rifle and told us to get on with it.’

‘Frenchy’ Ray emigrated to Australia from England in 1952, having been recruited directly into the Australian Army from Australia House in London. While he was an English citizen, he had been born in Paris and spoke fluent French, hence the nickname. Ray was an excellent shot and qualified as a marksman in his first range practice in 2 RAR, but he was made a sniper because he had told his superiors — untruthfully — that he had been a sniper in the British Parachute Regiment. He explained that, ‘as snipers our collective knowledge was rather poor. Apart from the fact that we were fairly good shots and keen to learn our trade, no-one could help us.’ He admitted that he operated mostly on instinct using his experience as a hunter. ‘I made many mistakes and was lucky I wasn’t killed. For example, I’d move into hides in daylight and probably under observation, and not have a clear, covered escape route. But then the battalion really didn’t know how to employ snipers either.’

Eventually the snipers helped to train one another. One would calculate a method of judging distance across the hilly terrain and pass it on to the others. They, in turn, would practise and improve on the original idea. One idea developed in 1951 saw the snipers use tracer rounds to indicate enemy mortar or machine-gun teams to the New Zealand and American artillery forward observers. They also experimented with the use of tracer ammunition to help them estimate distances, but with limited results. In January 1951, as the weather suddenly turned, the snipers had to learn to fight in the snow and freezing temperatures. None had experienced such conditions before and ‘the Western Australians and Queenslanders had the worst of it’. The challenges included coping with the sun glare off the brilliantly white snow and the tell-tale puff of snow emitted as they fired. They soon learnt that rubbing charcoal under their eyes could reduce the glare and that, by patting down the snow in front of the rifle’s muzzle, they could eliminate the white cloud emitted when the weapon discharged.

While one of the sniper pair would usually observe and the other fire, they also learnt to fire simultaneously where the situation warranted. For example, one tactic used when they could not agree on the distance to a target was for each man to adjust his rifle for his estimated range and both fire simultaneously. On other occasions both snipers might fire when they had two similar targets. Around dusk on the night of 13 July 1953, just prior to a major Chinese attack, Tupper and Ray spied two Chinese officers — at least they assumed they were officers. Tupper explained that, even though no-one wore rank in the field, it was often easy to identify enemy commanders by their mannerisms and the tell-tale signs of authority they displayed. In this case, the ‘officers’ were ‘carrying a large pair of binoculars, the other with a map case’. Both of the enemy were standing on top of their trench under the false assumption that they could not be seen. ‘What a beautiful target. Selecting one each, we fired simultaneously. They fell backwards in perfect unison.’

1 RAR sniper Private B. Coffman takes aim in Korea during the winter of 1951 (SLV 15246).

Some of the snipers even learnt to live in harmony with their enemy. In mid-July 1953, just after a Chinese attack, Tupper and Ray reached a quasi-truce with the Chinese opposite their observation post. They developed a set of signals to let the other side know if they were about to eat or rest so that they could keep the noise down, or if officers were visiting ‘so we’ll have to pretend to shoot at you. … You cannot live for weeks a few yards from one another without being friendly with your neighbours.’

Another burden for the battalion snipers was that, just as in the First and Second World Wars, the job was a lonely one. Kevin Tupper explained that ‘being a sniper was pretty isolating. You had your own mates in the sniper section, but few of the other blokes in the battalion had much to do with us.’ Robbie Robertson added that ‘Nobody likes snipers, you know … I’m not ashamed of it, but I don’t want to be called a murderer by some bleeding heart.’

Malayan Emergency and Indonesian Confrontation (1950–66)

In April 1950, following a communist insurgency which led to a state of emergency in Malaya, the British government requested assistance from Australia. Alongside the provision of air force support, Australia initially sent a small group of jungle warfare instructors and a signals unit, together known as the Australian Observers’ Unit. As part of Australia’s contribution to the Far East Strategic Reserve, to which Britain and other Commonwealth countries also contributed, 2 RAR was deployed to Malaya in October 1955. The battalion’s role quickly became one of counter-insurgency against communist terrorists, involving extensive patrolling, keeping a watch on the various villages in its area and generally denying the guerrillas access to their support base, the people.

From 1962 to 1966, Indonesia fought a small, undeclared war against the new state of Malaysia (the former Malaya, granted independence in 1963). Indonesia’s involvement eventually drew in Australia, culminating in the commitment of an Australian infantry battalion to Borneo in 1965. The Australian infantry battalions that rotated through Malaya between 1955 and 1963, and Borneo from 1965 to 1966, were organised according to the establishment and equipment tables for a tropical warfare infantry battalion. This establishment included a sniper in each of the infantry sections; however, these ‘snipers’ are probably best described as unit marksmen as they were never trained as snipers, did not operate as snipers and were not armed as snipers, with most carrying a standard SMLE or Owen gun.

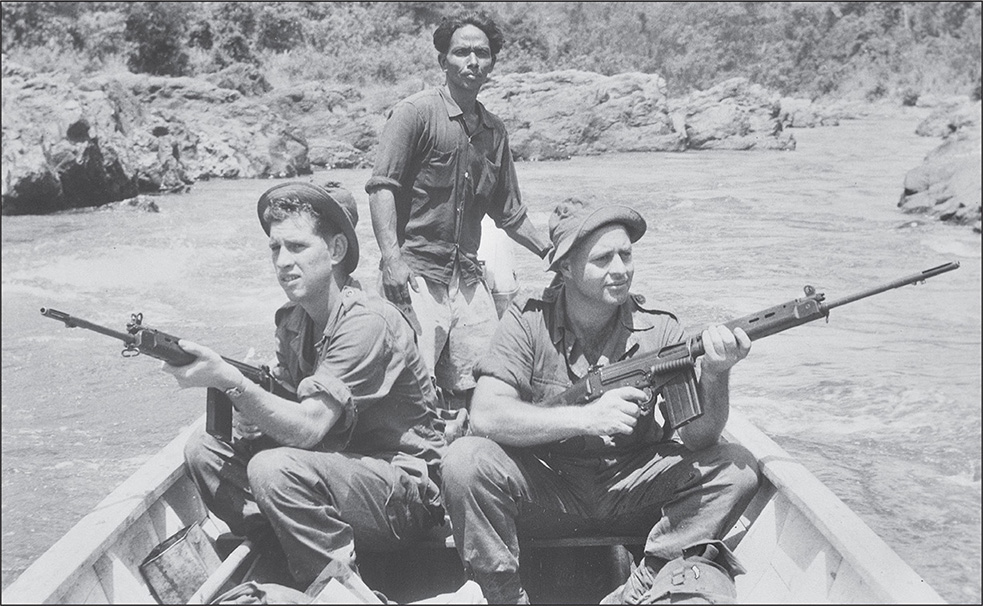

Two members of C Company, 1 RAR, patrolling a river in northern Malaya in 1961 with a local boatman. Both soldiers are carrying an L1A1 SLR (AWM P01306_028).

Vietnam War (1962–75)

Snipers were used most effectively by the enemy and by some US units. The nature of the war in certain parts of the province at times lent itself to sniper tactics. The enemy in small groups at medium to long ranges are ideal targets for snipers trained in teams and prepared to operate independently by teams.

Australian Directorate of Infantry, ‘Infantry Lessons from Vietnam’, 1972

In the post-Korean War period the Australian Army was involved in a variety of small-scale counter-insurgency operations in jungle terrain. Based on its experience in the latter years of the Second World War, and the lessons learnt from the British Army in Malaya during the Emergency, the Australian Army developed effective doctrine, training and techniques for this form of warfare by the time its first battalion was committed to the Vietnam War in 1965. However, as had occurred at the beginning of both the First and Second World Wars, the Australian Army entered the Vietnam War with no organised sniper concept or any specialist sniper capabilities.

Following the Army’s experiment with the concept of the pentropic division, the infantry battalion’s establishment reverted to that of the tropical warfare organisation in early 1965. This establishment was very similar to that used by the Army in the late 1950s and included, on paper at least, one sniper for each infantry section. In reality no snipers were ever trained, equipped or appointed during the Australian Army’s service in Vietnam, with one exception. However, battalion marksmen were employed on occasion, and some effort was made to trial different telescopic sights on the Army’s rifle, the 7.62 mm Self Loading Rifle (SLR) L1A1.

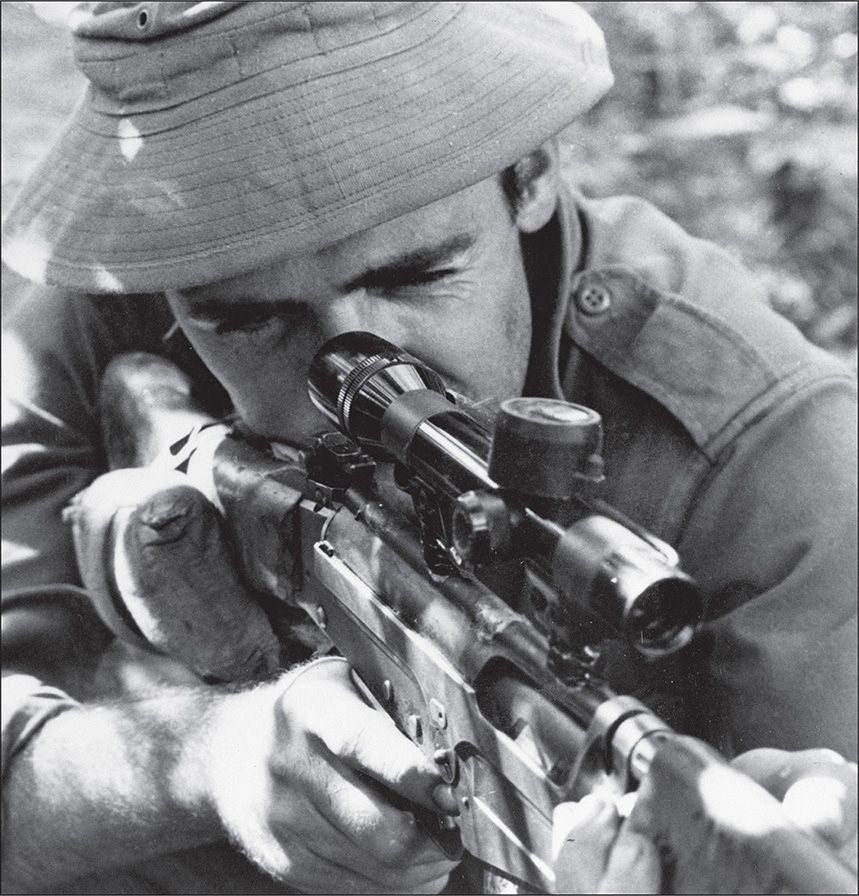

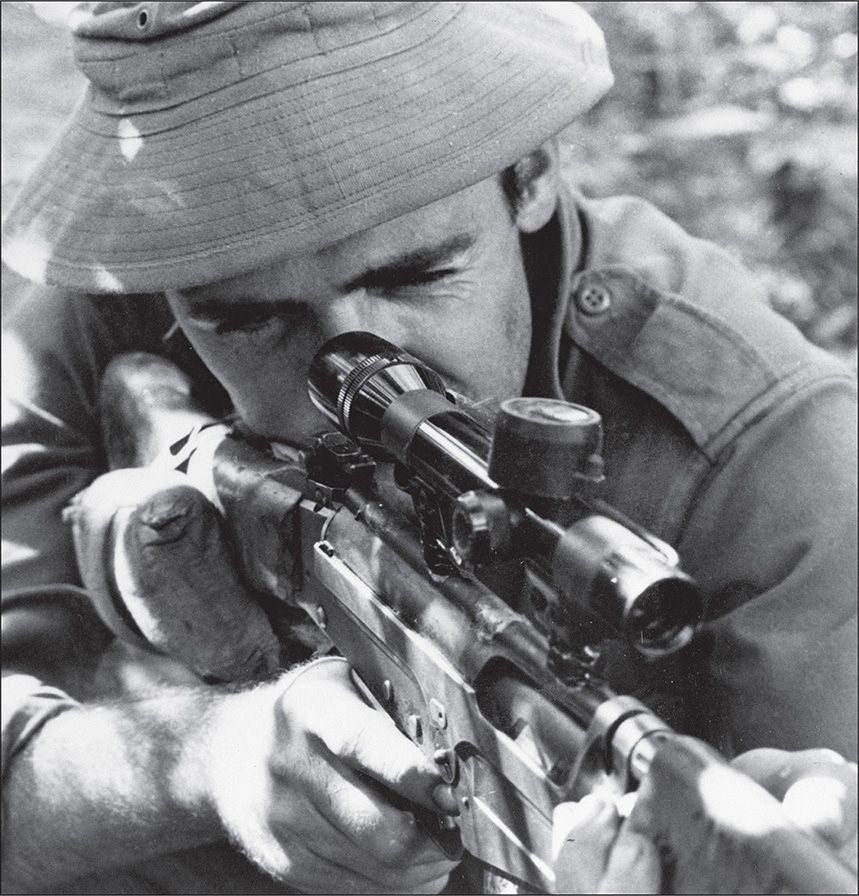

Private Ron Graham of C Company, 7th Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (7 RAR), based near the 1st Australian Task Force Base (1 ATF) at Nui Dat in 1971, sizes up a target through the 2.75 mm telescopic sights of his SLR L1A1. Battalion marksmen who trialled this weapon reported that the sights were excellent for targets beyond 300 yards and were often used for watching tracks (AWM CUN_71_0046_VN).

North Vietnamese sniping

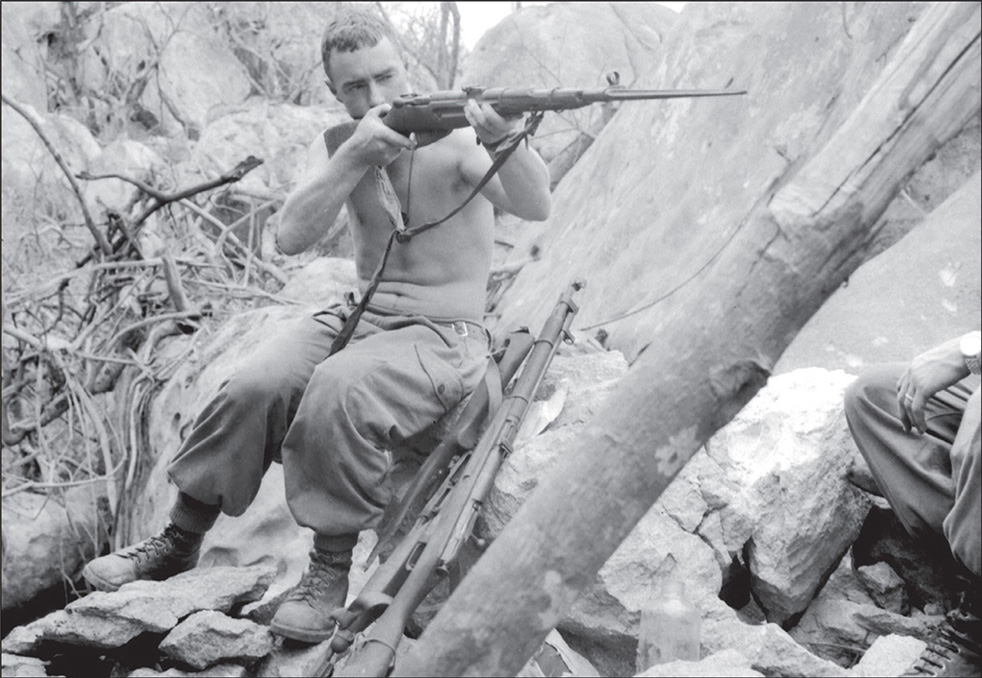

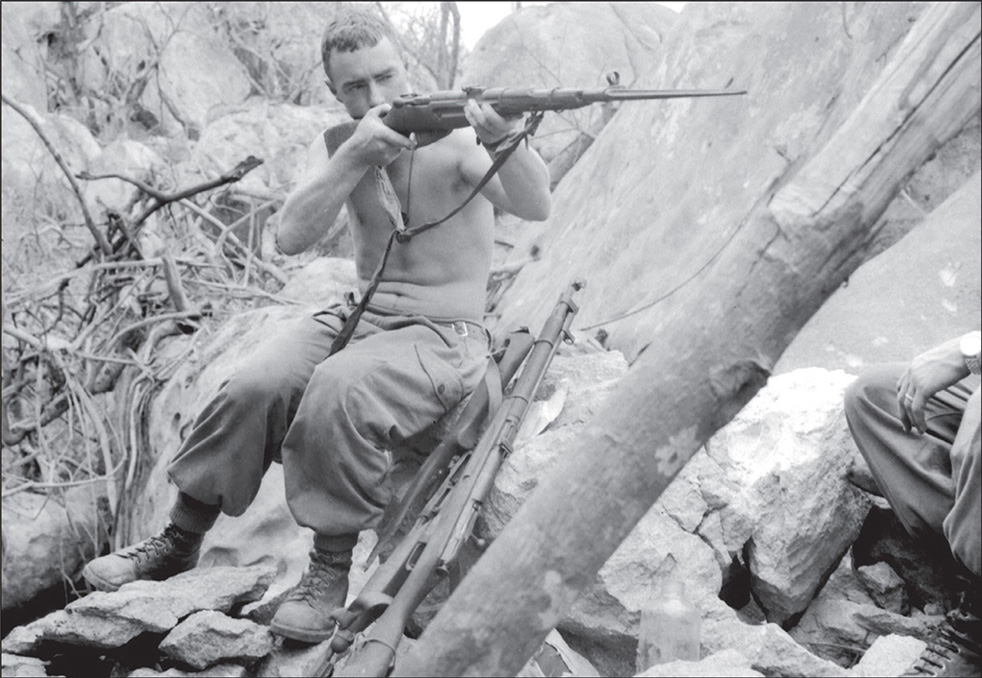

Private Graham Taylor of 3 RAR sights a Russian Mosin Nagant rifle captured in South Vietnam in 1968 (AWM CRO_68_0309_VN).

Numerous contemporary accounts of the Vietnam War, and several of the official histories, contain descriptions of ‘sniping’ by either the NVA or VC. Most of these accounts do not relate to trained NVA or VC snipers using specialist equipment, referring instead to incidents of enemy soldiers taking opportunity shots at anti-communist forces. However, both the NVA and VC did posses some talented snipers and specialist sniping rifles.

The most common sniper rifle in use by the communist forces was the vintage Soviet Mosin-Nagant 91/30 rifle, equipped with either a four-power PU or PEM scope. A variety of other rifles were used, including captured American Remington M700s. The NVA also had access to a very limited number of infrared weapon sight systems which were bulky, heavy, battery-tethered and a poor fit for their available rifles. The snipers were generally volunteers with their level of training varying from short marksmanship instruction to more comprehensive courses lasting several weeks.

The NVA snipers tended to be better trained and equipped and could be allocated to local VC units who provided the snipers with protection parties. Tactics typically involved lying in wait for lengthy periods in hides or, like the Japanese sniper in World War II, positioned in trees targeting tracks and trails known to be used by their enemies. Where employed within an NVA regiment, snipers would often deploy to the flanks of the unit and target enemy radio operators, commanders and machine-gunners.

While the Australians eschewed the use of snipers in Vietnam, partly due to the fact that they considered their area of operations unsuitable for sniper operations, the enemy did not. Both the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong (VC) employed snipers very effectively against the Australians, as was evident in numerous actions including 1 RAR’s operations at Long Dien on 22 August 1968, 9 RAR’s patrols in the Hat Ditch jungle on 8 February 1969, 6 RAR’s actions in early June and 5 RAR’s operations in June and November 1969.

Both the US Army and Marine Corps were also advocates of sniping in Vietnam, their sniper teams supporting US air-mobile infantry operations and conducting independent sniper tasks such as assassination, harassment and ambush. So successful were the American snipers that the North Vietnamese at one time placed a bounty on their heads. Several Vietnam-era snipers achieved legendary status in the US armed forces, such as Marine Corps snipers Charles Mawhinney and Carlos Hathcock. Mawhinney was credited with 103 kills in 1968–69, with an additional 216 recorded as ‘probable’. Hathcock achieved an official tally of 93 kills in two tours in 1966 and 1969, including the destruction of an entire enemy company over a five-day period, and the stalking and killing of an enemy general under extraordinarily dangerous conditions.

Carlos Hathcock was one of the US Marine Corps’ most successful snipers in the Vietnam War (Wikipedia Commons image).

It is clear that the US Army was keen to pass on its sniper experience and expertise to the Australians. In 1969, the Americans lent 1 ATF a total of 12 XM21 sniper rifles. These rifles were accurised1 sniper rifle versions of the US M14 rifle, capable of taking the standard NATO 7.62 mm ammunition and fitted with a three to nine-power Automatic Ranging Telescope (ART) variable scope. In early 1970 the US 25th Infantry Division invited four members of 8 RAR to attend its sniper school at Cu Chi.

XM21 sniper rifle

XM21 sniper rifle used by 8 RAR (AHU Image).

In the late 1950s, the US military replaced its M1 Garand rifle with a lighter, more accurate and semi-automatic rifle, the M14. The M14 held a 20-round magazine and used standard NATO 7.62 mm ammunition, the same ammunition used by the Australian Army in its L1A1 SLR. The early sniper variant of the M14, the XM21, was an accurised M14 with a walnut stock, free-floating barrel and modified rear sights, zeroed to use Match Grade (M118) ammunition. The XM21 was equipped with a Redfield/Leatherwood 3–9 power ART that was ranged between 300 and 900 metres and matched to the M118 ammunition. According to Army sniper instructor Russell Linwood,

A novel feature of the ART was that the scope reticules enabled quite accurate range estimation by quite simply comparing a standing target against the optic’s vertical marks. The range could then be ‘dialed-up’ on the telescope. The variable magnification further enhanced the firer’s capacity to engage the enemy accurately.

The telescope could be replaced by an AN/PVS-2 Starlight Scope and fitted with a Sionics suppressor for night firing. The Sionics suppressor replaced the standard M14 suppressor and resembled a can attached to the end of the barrel. While not a standard silencer it was designed to reduce both muzzle flash and blast, which it did very effectively. The Australian Army’s 8 RAR sniper team used a combination of the Redfield/Leatherwood and Starlight scopes (depending on night or daylight firing) and the Sionics suppressor in its sniper operations in South Vietnam in 1970.

Introduced in 1969 to meet the need for a new sniper rifle for use in South Vietnam by the US Army, and officially renamed the M21 in 1975, the XM21 was an effective, accurate and reliable sniper rifle, producing acceptable groupings out to 700 metres. It was the US Army’s main sniper rifle throughout the Vietnam War and remained in service until 1988 when it was replaced by the bolt-action M24 Sniper Weapon System.

On the night of 9 September 1970, the four Australian sniper novices, along with their American instructors, Captain Lomus and Sergeant Carrion, and a protection team from 8 RAR, deployed to the Nui Dinh Hills. According to Corporal Ron Goodall, who commanded the protection party, the area known as the Three Sisters afforded excellent observation and fields of fire:

My platoon was tasked to provide protection for the sniper group while they conducted sniper operations and also to ambush. The sniper group was commanded by Capt Lomus of the US Army [and consisted] of four snipers from 8 RAR … Capt Lomus and Sgt Carrion coached the two sniper teams, each team having a spotter and a shooter. The position we occupied was on high ground overlooking a vast expanse of paddy fields. The sniper teams mainly operated at night to cover any enemy movement from the hills to local villages. During the day the fields were being worked by the villagers. Unfortunately no enemy movement was detected by them for the two or three nights. On the third day my section was tasked to escort the sniper team to an RV with vehicles. They went back to Nui Dat. … The rifles the snipers had were the XM 21, an updated version of the M14. They were fitted with an ART 3-9 X telescope for day and a starlight scope for night, and a flash eliminator on the end. I first thought it to be a silencer. Each sniper had special ammunition designed for the task. Each round had to be accounted for.

Corporal Cliff Bond receives instruction in the use of the XM21 sniper rifle from Sergeant Carrion, US Army, while other members of the 8 RAR sniper team and Captain Lomus (US Army) look on. This photograph was taken in September 1970 after one of the 8 RAR sniper operations in the Nui Dinh Hills (image courtesy of the Commanding Officer, 8/9 RAR).

While this and a subsequent operation were unsuccessful, the potential for the use of snipers was not lost on several of the battalion’s officers and non-commissioned officers. The commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Adrian Clunies-Ross, reported that ‘the sniper team were a valuable addition to the Battalions [sic] potential effectiveness’. Major Mal Peck, who served two tours in South Vietnam and commanded Delta Company, 8 RAR, from 1969 to 1970, also attended the 25th Infantry Division’s sniper course at Cu Chi. He ‘agitated with the Infantry Centre when back in Australia about reintroducing sniper training as I felt it was a valuable capability and under-rated by Army, but US Army and marines had proved its worth in Vietnam.’ Major David Rankin, Officer Commanding Charlie Company, Mentioned in Despatches and a recipient of the Military Cross for his action with 8 RAR in Vietnam, also recognised the potential of sniper operations in Vietnam, provided the terrain was right. He had spoken to the 8 RAR men who had conducted the operation in the Nui Dinh Hills and advised that all were very impressed with the XM21 sniper rifle.

As the war drew to a close, the Australian military began to assess the lessons from its involvement in Vietnam. The Directorate of Infantry was responsible for a report entitled ‘Infantry Lessons from Vietnam’, written in early 1972 by Lieutenant Colonel R.A. Grey. The report contained the following brief reference to sniping in South Vietnam:

Snipers. Snipers were used most effectively by the enemy and by some US units. The nature of the war in certain parts of the province at times lent itself to sniper tactics. The enemy in small groups at medium to long ranges are ideal targets for snipers trained in teams and prepared to operate independently by teams. Some special equipment such as starlight scopes and noise suppressors to assist in concealing the sniper’s position would be needed. Likely tasks are:

a. In ambush as a team of three, by day and night. b. To cover the approaches to villages by night.

c. To disrupt enemy mining activity by teams in ‘hides’ close to enemy base areas. Interest in the art of sniping has declined in recent years in our Infantry. Perhaps it is time to revive it?

Nevertheless, several years would elapse before action was taken to reintroduce sniping into the Australian Army.

1 An accurised rifle is selected by the manufacturer based on its degree of accuracy in firing tests.