As a battalion commander in Afghanistan, my snipers were an important ‘force multiplier’. It was not just their marksmanship that I relied upon; it was also their value as an intelligence asset and their ability to detect changes in the complex environment in which we operated.

Colonel Jason Blain, DSC, CSC, Commanding Officer, Mentoring Task Force 1, January–June 2010

Iraq

The ADF’s commitment to combat operations in Iraq commenced in 2003 when a US led multinational force crossed into Iraqi territory in what the United States later called Operation Iraqi Freedom. Australia’s obligation included a headquarters element and forces from the Royal Australian Navy, Royal Australian Air Force and the Australian Army, under the codename Operation Falconer. The Army’s role was primarily the provision of a Special Forces capability consisting of a 500-strong Special Forces Task Group which operated as part of the Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force–West, supported by a troop from the Australian 5th Aviation Regiment and water transport.

Australian Special Forces were among the first troops to cross into Iraq during the invasion when elements of the 1st Squadron, SAS Regiment, deployed on 18 March 2003. The SAS was employed in combat operations in western Iraq, involving the location and destruction of Scud missile launch sites, the capture of the Al Asad airbase and active patrols of its sector. Each of the SAS patrols contained snipers. By April, with the fall of Baghdad and the end of combat operations, the SAS was withdrawn and a small security detachment (SECDET), based on 4 RAR, moved into the capital to protect Australian diplomats and aid workers.

In 2005, under Operation Catalyst, the ADF deployed a 500-strong battle group to Al Muthanna province to protect Japanese engineers and to train Iraqi military units. The Al Muthanna Task Group was based on 5/7 RAR and later 2 RAR, supported by some 40 ASLAVs and a training team. Almost a year later a slightly larger Australian force moved to the Tallil airbase and was renamed Overwatch Battle Group (West). The primary tasks of the battle group included the training and mentoring of the local Iraqi military and police, the conduct of security operations in Dhi Qar province and supporting US Special Forces operations in the province.

A 2 RAR sniper armed with his SR-98 sniper rifle conducts overwatch from a Baghdad rooftop during SECDET 2 in 2003 (image courtesy of Jason X).

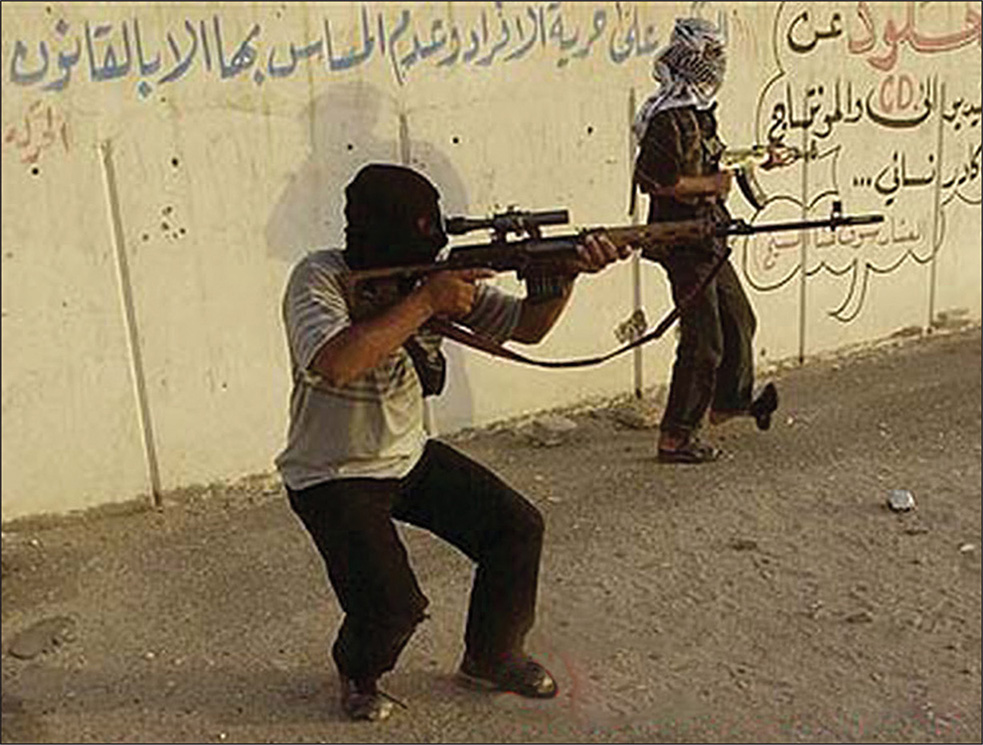

Each of these deployed infantry groups included sniper teams, as did most of the SECDETs. Their work was largely routine with lengthy periods dedicated to physical security, convoy protection and their share of ‘fatigues’, such as filling sandbags and mounting duties. This did not mean that the threat was low. The main threats to the force were assessed as vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices and stand-off attacks using mortars, rockets and even snipers. The use of small arms fire, including that of enemy snipers, was one of the deadliest of the enemy’s tactics in Iraq. This was made even more lethal by combinations of snipers and improvised explosive devices (IEDs). In a number of cases an enemy sniper would ‘overwatch’ an IED location to pick off the bomb disposal crews if the IED was spotted or, preferably, target coalition troops in the confusion caused by the explosion. Some enemy snipers also operated in teams, often using vehicles to move rapidly while another sniper covered their withdrawal. They also used ‘baits’ such as mock IEDs or bodies to lure coalition forces into a kill zone.

Designed in the 1960s as an infantry support or marksman weapon, the Dragunov eventually evolved into several sniper variants and was manufactured under license in a number of countries. One of these variants was the Iraqi-manufactured 7.62 mm Al-Kadesih sniper rifle which was used against coalition forces in Iraq (Wikipedia Commons image).

To deal with these threats, and consistent with Australian operational practice since the First World War, the battalion implemented an active patrolling program, both mounted and dismounted. These patrols were supported by new generation night vision devices, personal radios, interpreters and a public information campaign to win the support of the local population. The battalion’s snipers were an integrated part of the patrol program. The enemy, however, proved highly adaptable and changed their tactics at every opportunity. For example, in August 2007, a patrol from the US 1st Battalion, 30th Infantry Regiment, was targeted by a sniper. As the patrol began to clear the building from which the sniper had fired, there was a massive explosion which killed four US soldiers. The house had been heavily booby-trapped with four 155 mm artillery shells, and a message had been left in Arabic by the sniper — ‘This is where the sniper got you guys!’

To counter such actions both the Australian and US forces would often deploy their snipers in overwatch positions to reconnoitre routes, observe possible IED sites and other ‘hot spots’, and cover the movement of friendly troops. This was quickly recognised by the enemy who responded by placing IEDs in a number of the overwatch positions most likely to be used by coalition forces. In addition, as with our own sniper training, the Iraqi insurgent snipers would identify high-priority targets, such as commanders, and target vulnerable areas of the body that were not protected by body armour.

Iraqi insurgents. One is armed with an Al-Kadesih sniper rifle (Wikipedia Commons image).

On 26 September 2006 a large Australian force of some 60 infantry from 2 RAR mounted in Bushmaster Protected Mobility Vehicles and supported by ASLAVs from the 2/14th Light Horse Regiment (Queensland Mounted Infantry) travelled to the Iraqi Army barracks in Al Rumaythah to discuss training and reconstruction issues. As Al Rumaythah, a town of around 75,000, had a reputation for harbouring insurgents, the Australian force commander deployed his snipers in overwatch positions around the Iraqi barracks. The snipers soon detected several small groups of armed men that appeared to be observing the Australians and the barracks. Over the next hour more men gathered with several groups moving around the barracks in an apparent attempt to surround the Australians. While the snipers continued to observe the local men moving around their positions, a rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) was fired followed by small arms fire and more grenades. The Australians were now under attack.

The snipers returned fire in an attempt to keep the insurgents at a distance and prevent them from fully encircling the barracks but refrained from calling in the artillery, mortar or air support available to them for fear of injuring the civilian population. Attacked by a force of approximately 30 men, the snipers showed remarkable restraint, firing only where there was little risk to civilians. Three hours after their arrival in Al Rumaythah, the 2 RAR group was able to break contact and successfully withdraw. While the Bushmaster and ASLAV vehicles were largely responsible for preventing Australian casualties, the snipers managed to keep the enemy at bay while inflicting several casualties and identifying an exfiltration route.

In another example of the enemy changing their tactics after observing Australian patrol routines, on 23 and 24 April 2007 a 50-vehicle Australian patrol was attacked by RPGs. The RPGs missed and the patrol continued. Later that day on Route Bismarck, a secondary supply route in Dhi Qar province, the patrol was hit by a large IED which threw one of the ASLAVs off the road and set it on fire. As the convoy deployed against the attack, it came under small arms fire, including what some believed to be sniper fire. In the confusion, additional IEDs exploded, damaging two more ASLAVs. Further small arms attacks on other Australian patrols occurred later that night, culminating in a major attack the following day as the Australian battle group attempted to recover its damaged vehicles. Three Australians were wounded and a number of vehicles damaged in these attacks which reportedly involved as many as 30 enemy. An unknown number of insurgents were also killed.

The main Australian military commitment to Iraq ended in mid-2009, although a 110-man SECDET continued to guard the Australian Embassy in Baghdad and protect Australian diplomats and vehicle convoys until August 2011. A small sniper detachment supported the SECDET for much of this period.

Afghanistan

In the aftermath of the Al Qaeda attacks on the United States on 11 September 2001, Australia committed to an American-led coalition against terrorism. In December Australian Special Forces arrived in Afghanistan, withdrawing at the end of 2002. Royal Australian Navy and Royal Australian Air Force assets were also deployed under the Australian codename Operation Slipper. An Australian Special Forces Task Group of some 190 personnel returned for operations in Afghanistan in late 2005, increasing in size to around 300. In 2006, Australia also deployed a 240-strong Reconstruction Task Force (RTF), based on the 1st Combat Engineer Regiment with a force protection element. This task force quickly increased in size to over 400. Over the period of the ADF’s commitment to Afghanistan, the RTF underwent a number of role and name changes, first to the Mentoring and Reconstruction Task Force (MRTF) in 2009, and in 2010 to the Mentoring Task Force (MTF). All up, over 1500 ADF personnel were serving on Operation Slipper by mid-2009. All the major ground elements included snipers.

As in Iraq, the enemy in Afghanistan learnt fast. While numerous, enthusiastic and brave, they initially lacked training and effective tactics. This changed between the time Australia was first involved in Afghanistan in 2001–2002, and the ADF’s return in late 2005. In the intervening period the insurgents increased their level of military capability through hard-learnt lessons and astute observation of coalition tactics and procedures. For example, they adapted their own tactics as a result of observing changes in Australian patrolling habits, the changeover of battalions and even the arrival of new equipment. The Australians were regularly subjected to complex attacks involving the use of IEDs, machine-guns, RPGs and marksmen, all aimed at shaping the Australians’ reaction and testing for vulnerabilities. In the countryside the Australians soon learnt to watch out for small piles of stones placed by the insurgents at known fixed distances to enable them to accurately engage the Australian troops or vehicles as they passed.

The Barrett M82 anti-materiel rifle (Wikipedia Commons image).

Much press has been devoted to records of sniper hits, erroneously called ‘kills’, both in the numbers attributed to individual snipers and to the range at which a hit has been confirmed. As time and technology have advanced, so too have the confirmed ranges at which a sniper’s bullet has been observed to reach its intended mark. At the time of publication, this record rests with the Australian 2nd Commando Regiment.

On 2 April 2012, around 8.00 am local time, two sniper pairs and their commander achieved a remarkable feat in the Kajaki district of Helmand province, Afghanistan. The two sniper teams, located in separate hides, and their commander watched and waited. Finally observing the enemy, both teams made a final assessment, applied the data to their weapons and prepared to fire. In what is known as a command-initiated engagement, sniper team 1, with Private H on the rifle and Private M observing, and sniper team 2, with Lance Corporal S on the rifle and Corporal L observing, responded to their commander’s order to fire.

Over two kilometres away (2815 metres) and several seconds later, an enemy combatant was seen by all three observers to be struck by a .50 calibre ball round. The target was also directly observed to be bodily removed from the point of impact by other enemy, clearly unaware of where the bullet had originated.

How this amazing feat was achieved remains classified, but recently released metadata (technical data kept by most modern snipers) underscores the phenomenal combination of modern equipment, superb training, determination and tactical planning. The weapon used was a Barrett M82 A1 anti-materiel rifle with a Schmidt and Bender PM2 3-12 x 50 two-turn scope and Woods Reticle (modified mil dot).1 The observers used a Leupold 12-40 x 60 with Mil Reticle, and the ammunition was 12.7 mm MP NM140F2 Grade A.

The successful shot occurred at an altitude of 1160 metres with no allowance for wind. Data was taken from the JBM Ballistics site and tabulated for this particular weapon, a process that assists the firer to take account of a range of variables that increasingly affect a shot as the range to the target increases. It still took further remarkable human judgement to place the round where it was intended, given the stated capacity of the sighting system.

This shot surpassed the previous record of 2400 metres, also achieved by the same weapon in Afghanistan by another coalition army sniper.

A battalion sniper in an overwatch position in Afghanistan showing the typical terrain of Uruzgan province where the ADF spent much of its time (image courtesy of Jason X).

The terrain in the area of Uruzgan, where the ADF spent much of its time on operations in Afghanistan, was dasht (desert) with steep, rocky mountains. In this bare landscape the only fertile land lay in the river valleys where crops could grow and small villages were located. This narrow strip of fertile land was known as the ‘green zone’ and was often where the Taliban was most active. This terrain had advantages and disadvantages for the long-range sniper. The open nature of the country aided observation and firing, enabling the ADF snipers to engage targets at the maximum range of their sniper systems if necessary. However, the lack of vegetation made concealment more difficult and increased the dust signature when firing. It also made it next to impossible to judge the strength and direction of the wind. Strong, gusty and unpredictable winds, often blowing at 30–50 kilometres per hour and frequently changing direction, were a constant challenge to snipers operating in the rural areas of Afghanistan. The absence of trees to act as a wind indicator meant that the snipers would revert to watching through their binoculars or telescope, looking for the small puffs of dust caused by the movement of goats, or even the clothing of the shepherds. At least one sniper pair used an old trick once employed by the Boers in their wars with the British, placing small pieces of rifle cleaning cloth on sticks as their ‘wind sock’. ‘These were too small to be seen by anyone unless you knew where to look, and they could also be used to judge distance and as reference points on that bleak landscape,’ advised a battalion sniper.

Operation Baz Panje (Falcon’s Talon) provides a clear example of the role played by the sniper in a battalion operation in Afghanistan. This operation involved a joint Australian–Afghan National Army (ANA) battle group consisting of elements of the Australian MRTF 2 based on 1 RAR, with combat engineer and armour support, and an ANA infantry company with engineer support. The operation was supported by the Australian Special Operations Task Group (SOTG) which provided early reconnaissance prior to the deployment of the joint battle group, and a US aviation battalion equipped with attack and utility helicopters. The operation was conducted during the period September to December 2009, with the aim of extending the ANA’s control and influence through the Mirabad Valley. This involved clearing the enemy from the area, winning the trust of the local population and the construction of a large patrol base for the ANA.

The threat was well known. While this included direct engagement with enemy forces, the highest threat was from IEDs that targeted both dismounted infantry and their vehicles. In the two months preceding Operation Baz Panje, MRTF 2 had lost five Bushmasters, had a crew of one Bushmaster and a dismounted soldier sustain serious injuries, and had suffered its first death, all from IEDs.

The battalion’s eight snipers — four pairs and their sniper supervisor — played an important role in this operation. In the initial phase the snipers were deployed to help cover the gaps between the various infantry platoon locations. This usually involved the sniper teams operating from an overwatch position from which they could cover the gaps by observation and fire, provide early warning of any enemy attempts to infiltrate the area and disrupt or destroy any counter-attacks. Due to the enemy’s tactic of placing IEDs in what they assessed were likely coalition overwatch or fire support locations, the snipers had to be attuned to any changes in their environment and always on the watch for booby-trapped locations. Following the insertion of the battle group, the snipers participated in the clearing phase of the operation by contributing to the patrol program, either participating directly in patrols or deploying to hides and overwatch positions well ahead of the patrol. In this latter case, the snipers would watch for any suspicious activity ahead of the patrol’s route, particularly at the various crossing points used by the Australians and the ANA.

1 RAR snipers move into position near Sarab, Afghanistan, in 2009 (Land Warfare Studies Centre image).

Throughout the operation the snipers assisted their battalion to develop methods of asserting a more persistent dismounted presence within the green zone. This was not only aimed at isolating and disrupting the enemy, but also at both protecting and gaining the trust of the local population. Lieutenant Colonel Peter Connolly, Commanding Officer of MRTF 2, explained that, after some trial and error, the most a successful method was found to be the insertion of dismounted platoon-sized groups, both Australian and ANA, into specific areas for up to two months. Supported by small specialist teams such as snipers and engineers, these dismounted patrols were able to dominate the surrounding area and isolate the Taliban from their support base. Intense patrolling uncovered over 50 weapons caches and discovered and disarmed 15 IEDs in two and a half months. Most notably these techniques forced the Taliban to change their tactics as they resorted to stand-off small arms attacks which were defeated or rendered ineffective by the patrols’ fire discipline and their integral support weapons such as the 81 mm mortar, 40 mm automatic grenade launcher, .50 calibre machine-guns and snipers.

In his 2011 paper, Counterinsurgency in Uruzgan 2009, Colonel Connolly highlighted some of the key tasks his snipers performed during Operation Baz Panje:

They were employed extensively on patrols within the green zone to ‘satellite’ the supported patrol and remain offset from the main body to look for RC [remote controlled] / CW [command wire] IED ‘trigger men’. Snipers were specifically employed for counter-IED operations, and to contribute a layer of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance for major deliberate operations, such as Operation BAZ PANJE.

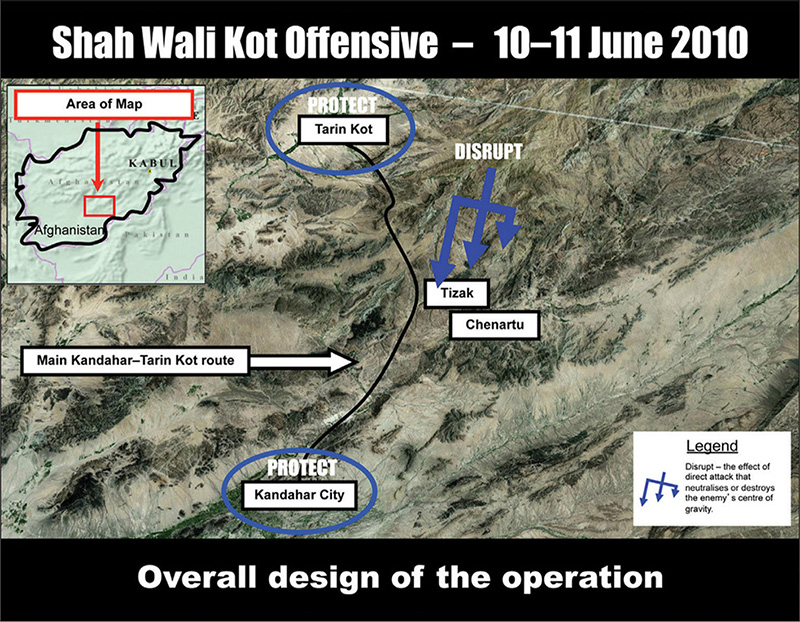

SOTG snipers also played a key role in another operation known as the Shah Wali Kot offensive in May and June 2010. The Shah Wali Kot had been identified as an insurgent crossroad between Tarin Kot in the north, Kandahar City in the south and Helmand province to the west. The SOTG’s role in the offensive was to disrupt the enemy and protect the northern approaches to Kandahar City. The offensive involved Australian soldiers from 2 Squadron, SASR, and A Company, 2 Commando Regiment, supported by members of the Afghan National Provincial Police. The operation commenced with the commandos moving openly into the villages on the route and gathering intelligence from the locals. Eventually an intelligence picture emerged that suggested that the Taliban might attempt to engage the Australians in a decisive battle.

The first engagement occurred in the early hours of 10 June, when the enemy attempted to probe what appeared to be an exposed commando sniper position within the village of Chenartu. Sniper team commander Sergeant Garry Robinson and his observer engaged the enemy, killing three. An intense firefight developed which quickly resulted in the deaths of three more enemy. Sergeant Robinson recalled the intense heat during the battle, which reached more than 50°C. ‘The conditions were trying to work and fight in,’ he said, ‘it was very dry and dusty.’ By 10.00 am all the commandos were under attack from small arms, heavy machine-guns and RPGs, and it was clear that a larger enemy force was moving in to reinforce their attack. Later that afternoon an even more coordinated and aggressive attack was launched by the enemy. Lieutenant Colonel Paul Burns, Commanding Officer of the SOTG, described the scene: ‘The entire position is engulfed in a hail of fire again, but more coordinated and precise this time because [the insurgents have] spent the day doing their reconnaissance and mapped out every single position … Every single commando position was pinned down pretty much by heavy machineguns or rocket propelled grenades.’

Overall design of the Shah Wali Kot offensive, 10–11 June 2010 (Army News image).

As the commandos fought to regain the initiative, air strikes were called in but there were no reports of sightings of any of the Taliban commanders. This was significant as one of the SOTG missions was to kill or capture the Taliban leadership. However the opportunity to achieve this mission came the following day, as Lieutenant Colonel Burns later explained:

On the morning of 11 June, we started to notice about 5 km away … in the small village of Tizak some concentration [of enemy] and a lot of movement. We got some indications that there were a couple of key Taliban leaders in the area. It was at that point that I launched 2 Sqn [2nd Squadron SASR] soldiers to go and do a capture-or-kill mission on those commanders.

Adopting a key role in this mission was an SASR troop equipped with a machine-gun and several sniper systems. ‘The troop commanders … immediately directed the guys to suppress the machine-gun positions down in the valley and up in the high ground,’ recalled Lieutenant Colonel Burns. The snipers played a critical role in suppressing enemy fire while the assault force attacked the enemy positions and drove the enemy from the village. The commandos similarly overpowered the enemy force in Chenartu and pursued the enemy.2

An SOTG sniper takes aim during the Shah Wali Kot offensive (Army News image).

Throughout the various deployments to Afghanistan, the snipers continued to operate as an integral part of the battalion’s patrol program and support the battalion’s operations, working from a series of hides and overwatch positions. They usually operated in pairs or quads, sometimes in conjunction with either Special Forces or Dutch snipers, or augmented by support weapons, a Joint Fires Observer, engineer and/or signaller. On 4 December 2010, for example, a joint patrol of 11 Australian and 15 ANA soldiers left Patrol Base Anarjoy to patrol towards the town of Derapet some three kilometres away. The group contained a sniper quad (team of four) from 5 RAR. Early in the patrol the sniper team leader, Corporal Ryan Avery, decided to split the snipers into two teams, as ‘there weren’t many Australians on the patrol and we wanted to put the .338 Blaser sniper rifle in an overwatch position while myself and [Private] Grant Robbins, with our semi-automatic SR-25s, moved with the patrol members on the low ground.’

As the patrol entered Derapet it was immediately apparent that something was wrong. ‘We started seeing a lot of vehicles and families moving out of town, which was a sign to us that something was going to happen.’ It was at this point that the two snipers in the overwatch position reported that a large group of insurgents was approaching the town from the north. Soon after, the patrol came under heavy small arms, machine-gun and RPG attack. The patrol conducted a fighting withdrawal, covered by the snipers in the overwatch position. They were under intense pressure until two AH-64 Apache helicopters arrived and strafed the enemy with their 20 mm cannons. The firefight lasted around three and a half hours, with all four snipers escaping unscathed. Corporal Avery was awarded a Medal for Gallantry for ‘his fearless action in repeatedly exposing himself to enemy fire to better engage his opponents and protect the lives of his patrol mates.’

Independent sniper operations would often be within range of a Quick Reaction Force, battalion mortars or air support — sometimes all three. On occasions an infantry team, supported by a Bushmaster, would be tasked to provide protection to a battalion or Special Forces sniper team, to stand by out of visual range to assist in extracting the snipers should they require it, or to act as a cut-off for ‘squirters’ (enemy trying to flee the area).

Medal for Gallantry recipient Corporal Ryan Avery, second from left, with his 5 RAR sniper team members in the Tangi Valley, Afghanistan, in 2010. The three men on the right are carrying the SR-25 equipped with a Schmidt and Bender scope. The man on the left is holding the barrel of a .338 Blaser (Army News image).

In Afghanistan the Australian snipers were able to support a diverse range of mission profiles due to their ability to provide real-time intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, and to deliver precision fire against threats at a distance. To perform these missions the Australian Army sniper has at his disposal an impressive arsenal of weapons. These include both anti-personnel and anti-materiel sniper rifles. For example, both the Accuracy International AW50F and the Barrett M82A1 are 12.7 mm (.50 calibre) anti-materiel rifles commonly used to destroy enemy equipment such as light vehicles, radar installations, ammunition dumps and 107 mm rocket sites at extreme distances. The .338 Lapua Magnum Blaser 93 Tac 2 sniper rifle was also available and was used effectively in both the anti-personnel and anti-materiel roles. These larger calibre weapon systems enable the sniper to fire over long distances, which was often necessary due to the lack of cover in the open Afghan terrain. It was not uncommon for the sniper to be over a kilometre from a potential target.

A 2 RAR sniper fires his AW50 anti-materiel rifle during a live fire demonstration (AHU Image library).

A variety of anti-personnel weapons systems are also available to Australian snipers and marksmen. All 7.62 x 51 mm NATO calibre, these systems include an Australian variant of Accuracy International’s AW SR-98, Knight’s Armament Company’s SR-25, Heckler & Koch HK417 Marksman Rifle System and the Mark 14 Mod 0 Enhanced Battle Rifle (EBR).

The ability of the snipers to quickly deploy anywhere in the ADF’s area of operations also enhanced their operational flexibility. In Iraq or Afghanistan snipers, particularly Special Forces snipers and scouts, could be deployed in a variety of ways. These included high-altitude low-opening parachute drops from fixed wing aircraft, rappelling or landing using rotary wing aircraft, insertion from small watercraft or submarines, and operating from a variety of vehicles, including the Bushmaster, and motorcycles such as the ATV (all-terrain vehicle) quad bike. Regardless of the high-tech transport options available, the sniper often had to simply ‘hoof it’ — walk long distances to his objective. This could involve travelling several kilometres during the night while carrying heavy loads, including several litres of water, extra ammunition and rations, surveillance and other electronic equipment, and radios. For the battalion sniper in particular, this could also mean wearing bulky, warm clothing, depending on the season, and body armour. Body armour, even the light plates, posed a problem in Afghanistan. It inhibited speed and agility, increased weariness and fluid consumption and could cause injuries when the wearer was moving fast or ‘hitting the dirt’. ‘In cities it ain’t so bad, but in the mountains of Afghanistan body armour can be a pain. It just gets in the way and slows you down,’ commented one sniper. While the Army is examining ways to reduce the weight and bulk of body armour, and there have been some advances in this technology, the use of body armour by all members of the ADF is a force protection issue and has been proven to save lives.

Top: an Australian Special Forces sniper team, equipped with a Blaser R93 LRSR 2 .338 Lapua Magnum sniper rifle, operating in Afghanistan in 2008, and (bottom) a 6 RAR sniper firing a Blaser during a sniper competition in 2012 (Defence Public Relations images).

The Blaser suite of bolt-action precision rifles is manufactured by Blaser Jagdwaffen GmbH of Isny, Germany. The R98 LRS (Long-Range Sporter) 2, which is a slightly enhanced version of the Tactical 2 sniper model, is used by the German and Dutch police forces, the Australian Special Forces and some Australian battalion sniper teams. Both models derive from Blaser’s successful sporting and competition rifles and incorporate the company’s unique ‘straight-pull’ bolt action designed for a faster ‘follow-on shot’ than is generally possible with more traditional bolt actions. While both weapons are available in a range of calibres, the Australian Army employs the powerful .338 inch Lapua Magnum cartridge.

The Blasers in use by the Australian Army are fitted with the standard Australian sniper specification scope, the Schmidt and Bender 3–12 power, and can also be fitted with a muzzle-break and a Harris bipod. The stock is fully adjustable aluminum with a skeleton architecture and is finished in a black synthetic coating for grip.

While sniping operations in the Uruzgan countryside were not without their challenges, the snipers soon adjusted. However, as the Australian Army had experienced in operations from Vietnam through to East Timor, a key issue in urban operations was how to ‘fit in’. As one battalion sniper commented eloquently,

In Afghanistan we stood out like dog’s balls. … Any strangers were instantly identified, which made the working out of hides or in overwatch positions around the Green Zone [where the majority of the Afghans lived and worked] bloody tricky, and hiding in the dasht in daylight often impossible.

Consequently, much of the snipers’ movement and operations had to occur at night with the operators remaining hidden, or at least inconspicuous, if possible during the day or withdrawing during daylight hours. In a high-threat environment a sniper pair might also be allocated a protection party or operate as a team of four or more.

Corporal Shane Brown, a sniper with RTF 4 in 2008, in the mountains near the joint patrol base north of Tarin Kowt, Afghanistan. He is armed with an SR-25 and carries a Browning 9 mm pistol in the pocket of his body armour (Department of Defence image 20080619adf8239682_417).

The use of hides by snipers became common in the First World War, and they remain an important aspect of modern sniper operations. The sniper, particularly a Special Forces sniper, may lie in a hide and remain motionless for hours or even days at a time and will often have to ‘bag’ and remove his own excrement and urine, particularly if he plans to reuse the hide. Some snipers even resort to taking anti-diarrhoea medication such as Imodium to reduce bowel movements while operating from a hide. One battalion sniper described his work in Afghanistan operating from hides as ‘cramped, uncomfortable, too hot or too cold, extraordinarily boring for hours, interspersed with seconds of a real adrenalin rush’.

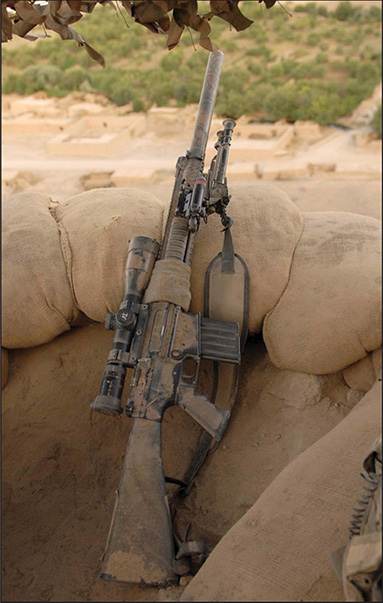

An SR-25 sniper rifle still covered in dust from an operational patrol near Baluchi, Afghanistan, during RTF 4 in June 2008 (Defence Public Relations image).

The Knight’s Armament Company SR-25 Mark 11 Model 0 is an anti-personnel sniper rifle available to Australian Special Forces, battalion snipers, and marksmen deployed on active service. It is a gas-operated, semi-automatic rifle with a detachable sound suppressor, Harris bipod and a 20-round magazine. Chambered for 7.62 x 51 mm ammunition, it performs best with the M118 long-range ammunition which is match-grade military ammunition produced to exacting standards for snipers. The SR-25 was initially supplied to Australian forces in the Middle East equipped with the US-specification Leupold Vari-X mil dot telescope sight. This sight was later replaced by the Australian-specification Schmidt and Bender 3–12 power telescope.

The rifle’s ancestry clearly shows the influence of the Vietnam-era M16 and AR-15 rifles. Developed in the 1990s, it was initially accepted into service by both the US Navy and US Marine Corps and first used on operations in Somalia in 1993 by the US Navy SEALS. The US Army has also adopted the rifle for its snipers and it was first issued to Australia’s Special Forces for operations in Iraq. In the ADF this issue was later extended to battalion snipers and marksmen working with the Overwatch Battle Group in southern Iraq and the SECDET in Baghdad. The SR-25 is also on issue for operations in Afghanistan.

The Australians welcomed this rifle as it provided an alternative to the in-service but aging SR-98. In particular, they liked the rifle’s ability to use semi-automatic fire when required. They were also drawn to the quick release sound suppressor that both masks the sound of the shot and almost completely eliminates flash, thereby assisting to conceal the firer’s position. The suppressor effectively acts as a muzzle brake which reduces recoil, enabling more accurate and faster ‘rounds down range’. Another advantage of the SR-25 over the SR-98 is the Picatinny-Weaver long-rail system which allows various attachments such as the Universal Night Sight – Long Range. Although the accuracy of the SR-25 does not match the SR-98, it can reliably and effectively engage targets up to and beyond the weapon’s advertised effective range of 600 metres in the hands of a competent sniper. Some snipers have achieved a 13 mm grouping at 100 metres which represents an excellent level of accuracy for a semi-automatic rifle.

Whether shooting from hides or other positions, the snipers rarely had the luxury of time to set up their shots and fire with leisure. The basic requirement was for two main types of sniper engagement: rapid shots where the firer quickly adjusts his sight picture based on known distances, such as indicated on his range card, and wind estimation; and deliberate fire involving lasering the target to gain the range, using a wind meter to indicate wind speed, and then entering this data on his scope. In both cases the sniper has to identify the threat; select the target; estimate and allow for range, wind and temperature, and successfully engage his target. All of this needs to be done within seconds and at distances usually beyond 600 metres for 7.62 mm sniper systems and 1500 metres for the heavier calibre 12.7 mm, commonly referred to as ‘50 cal’ or .50-inch weapons.

However, snipers are not restricted to these two forms of shooting, as one particularly memorable example illustrates. One of the Australian Army’s recent recipients of the Victoria Cross, Corporal Benjamin Roberts-Smith, was also awarded the Medal for Gallantry on his second operational tour of Afghanistan in 2006. Acting as a Special Forces patrol scout and sniper, then Lance Corporal Roberts-Smith was operating from an observation post in rugged terrain near the Chora Pass, Afghanistan:

As enemy militia repeatedly attempted to outflank the post, he moved several times to exposed positions where he effectively employed his sniper rifle to hold off the enemy advance. For his display of gallantry in disregarding his own personal safety in maintaining an exposed sniper position under sustained fire he is awarded … the Medal for Gallantry.

Corporal Benjamin Roberts-Smith VC, MG, Commendation for Distinguished Service with the SOTG during operations in Afghanistan in 2000. He is carrying an M14 EBR with a synthetic stock, Picatinny rail, EoTech holographic weapon sight and magnifier, and an AN/PEQ2 designator/illuminator on the side. The EBR is not a sniper rifle but a 7.62 mm marksman or assault rifle (Department of Defence image 20100406_8255596_1715-1).

Another key task of the snipers attached to the MTF was, as the name implies, training the ANA in marksmanship. Soldiers from MTF 1 conducted a 16-day course to teach ANA soldiers from the Afghan 4th Brigade the art of marksmanship. Most of the Afghan students, while excellent marksmen, had not used a telescopic sight before nor had they been provided any formal marksmanship training. This new capability enabled the ANA to provide overwatch for its patrols and to engage targets at extended ranges.

Snipers from MTF 1 instruct members of the ANA’s 4th Brigade in marksmanship during a mentoring session in the Baluchi Valley region. The ANA soldiers are using 7.62 mm Remington 700s (Department of Defence image 20100831adf8115142_062).

The history of sniping has clearly shown that, while the sniper’s marksmanship is of critical importance on the battlefield, it is this combined with his value as an intelligence asset that makes the modern sniper a force multiplier. This was certainly the case in Afghanistan where the snipers were routinely used as part of the battalion or formation’s intelligence collection plan. Their use of powerful optical devices, video and GPS technology, and the ability to provide imagery in real time, made them an important intelligence resource. In this way they could act as the eyes and ears of a patrol on the ground through the provision of video imagery and GPS coordinates, identifying potential threats and, if necessary, eliminating them at a distance. MRTF 2 Commanding Officer Lieutenant Colonel Connolly highlighted the value of his snipers during his battalion’s tour of Afghanistan: ‘Having snipers as an organic intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance capability who were also capable of surgical kills in the populated green zone was invaluable.’

Other tasks or positions were often ‘intel led’, meaning that the snipers would deploy based on intelligence that something was likely to occur either at a specific location or within a defined area. This could be the possible presence of a high-value target at a village house, a weapons buy in a bazaar, or just the presence of strangers in a village. An Australian Army sniper who completed two tours in Afghanistan, explained that:

We would set up to provide overwatch for one of our patrols who might be on foot or even in vehicles, or establish a hide just to keep an eye on an area where there had been some recent enemy activity, such as the placing of IEDs, where we suspected the bad guys were entering our area of ops, or if we were looking for a particular individual. … We used video to identify some suspicious characters, or to just confirm that a particular person was in the area. … From a hide or an overwatch position we could also provide the coordinates for a patrol to intercept or for joint fires [this could include mortar or artillery bombardment, or an aircraft or drone strike], or to cut off the squirters.

Just as the Australian Army sniper was trained in 1916 to ‘note everything that happens in your area; know your and your enemy’s routine and be on the watch for any changes in that routine, or anything out of the ordinary’, so the modern sniper’s ability to become attuned to his environment and observe even minute changes is vital in the complex operating environments of the twenty-first century.

1 A mil dot enables a rifleman to estimate the distance to a target using the image (reticle) he can see through his telescopic sight, and to quickly adjust his fire.

2 Image and story reproduced with kind permission of Army News, 23 May 2013.