Chapter 3 Work Your Program

By the time you start a PhD, you’ve already had close to two decades of education, going back to nice Mr. Clarke in kindergarten, so it all seems pretty familiar. With five or more years of university education completed, it may be tempting to see the PhD as more of the same: You take some classes, read some books, take a test, and write a long paper (or set of papers). But the PhD is fundamentally different from anything you’ve done before, moving you from student to … something else—ideally, a career professional, who is a combination of independent actor, scholar, and general force of nature. The PhD is uniquely open ended and you become more of your own agent over time, with tremendous freedom to manage (or mismanage) your doctoral experience.

Working your program is about making small and large decisions that subtly but importantly help you make this transition from student (with limited agency, following the directions of others) to professional (with agency, making strategic decisions for your long-term goals). We have been encouraging you to be thoughtful and strategic as you make choices, always asking, given both my future goals and the information currently available to me, what is my best decision right now? There are a number of important decisions you will make during your program, and these will be the focus of this chapter. And there is a key (but jarring) question that you need to make at different stages: Should I continue in my PhD program? Every PhD student needs to ask this in their own self-interest, but rarely feels permission to do so. We give you that permission. You alone know your best interests, and we encourage you outright to ask it regularly, and to answer it honestly. It’s crucial to successfully working your career.

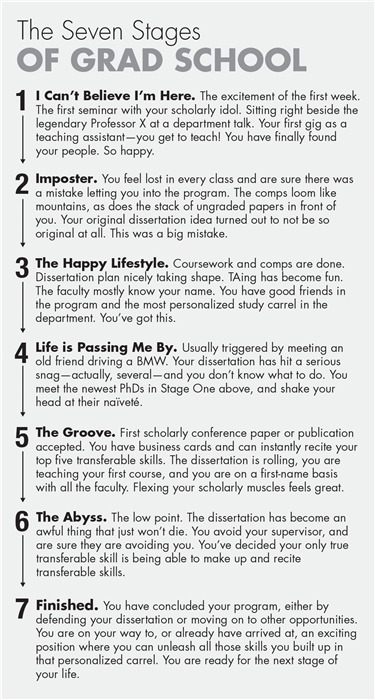

Figure 3.1: The seven stages of grad school

How do I select the best courses to advance my future career?

Doctoral coursework has two somewhat contradictory purposes: to broaden you as a scholar on the road to mastery of the discipline, and to support your specific area of interest and dissertation. Ideally, you will leave the coursework stage of your PhD with four things: course credit toward your degree (bare minimum); increased content and disciplinary knowledge; concrete evidence of skill advancement; and a roster of strong referees for your future job searches based on the positive relationship you developed with each course professor.

The amount and type of coursework required can differ considerably across both disciplines and individual programs. Some programs have a common curriculum that all PhDs take with few options; others offer an array of choices, usually organized by disciplinary field; and some, especially interdisciplinary programs, essentially direct you to the graduate course calendar and tell you to design your course plan. The type of courses in a PhD program may include the following:

• Program-wide courses (often mandatory): surveys of the discipline; general research methods; dissertation-development courses

• Field courses: surveys of a specific subfield

• Skill courses (usually tied to your dissertation project): languages, specialized methodologies

• Elective courses: a chance to either deepen or broaden your learning

Your course selections, especially in smaller programs, may be fairly limited, but usually you have some choice. How should you make those decisions? Start by considering your coursework as a whole, rather than just a bunch of parts. Think of courses in terms of both content and skill development and assess your potential courses accordingly. This approach allows you to identify content redundancies (e.g., three courses on Bushwackian theory) and gaps (no courses on Bushwackian history) and skill redundancies (e.g., four courses developing critical thinking and communication competencies) and gaps (no courses developing global fluency). This information allows you to strategically select courses that will allow you to create the knowledge, experiences, and evidence you wish to possess at the end of your program.

To do this type of assessment requires some work on your part before making your decisions. Ask for the course syllabus (or a past version) and ask around. What is the course like? What are the expectations and demands? Look for at least some courses that look different from one another and that ideally do all of the following: (1) develop or enhance a clear skill that is (2) applicable in some way to your dissertation and (3) tangible and transferable to your broad career goals. When possible, aim to pick something more applied as opposed to yet another seminar where everyone sits around talking about the weekly stack of readings with two presentations each per term; you are likely to be sufficiently exposed to that format in your mandatory courses.

As you explore options, look into whether you can take courses outside your program. There can be some giant pitfalls here, especially if you have no background (i.e., undergraduate courses) in the other discipline—in which case you may find yourself quickly drowning in their unfamiliar approaches, assumptions, and terminology. But if you see some clear connections with your interests and ambitions (and, ideally, a skill), consider branching out.

Even with these assessments complete, you may have options from which to select. Here are some additional factors to consider:

• Secondary subjects: There can be value in taking a course in a secondary subfield; you learn new knowledge and it might help position you in the academic job market. That being said, don’t let it override other criteria; “positioning” is an extraordinarily imprecise game, so don’t let it alone drive you into courses that do not excite you or do not clearly provide a tangible payoff.

• Cross-cutting subjects: You may be really interested in Topic X, but while various courses touch on X, there is no course specifically on it. You can only select one or two courses, and the choice feels arbitrary. This dilemma is not uncommon, especially if your interests clearly straddle different fields or subfields without a clear home. In this situation, ask yourself which course will be most energizing, engaging, and likely to build the best skills. And the bigger question to ask is whether the cross-cutting topic is truly your focus or whether there is another way to frame your interests.

• Instructor: Should you follow the undergraduate mantra of “take the professor, not the course”? Yes and no. A good teacher typically makes for a good course, though at the graduate level much depends on the particular student cohort in a small class. Graduate courses do offer great chances to impress and connect directly with faculty and build relationships with them, leading to possible future supervisors or committee members, research work, and handy reference letters and introductions to their networks. However, you will have numerous opportunities outside the classroom to interact with faculty, so signing up for Professor Great’s course just to get to know her is not always necessary (especially if you’re less than completely enthusiastic about the course content, in which case you may un-impress her).

• Grades: Should you take courses that risk a lousy grade that will impact your future? You have surely already spent much time wrestling with this basic existential question of university education. Grades become less important as you advance in your career, but they still matter, particularly for scholarships. Answer the question however you answered it in the past, since that strategy successfully got you to this point.

• Auditing: While auditing can be a great way to expose yourself further to new and less-familiar ideas (and faculty), without the discipline of grading you are less likely to develop actual new skills and outputs. And while it may be a pleasant three hours every week sitting in on discussions about a mildly interesting topic, your time is likely better spent elsewhere.

What skills will help me excel in my classes?

Courses ideally offer you opportunities both to work with content and to build skills. If you focus on the skill building and keep up with the material, your chances of excelling are greater than if you just aim to keep pace with the material. This is admittedly hard to keep in mind when you look at a huge required reading list. But as with everything, we urge you to think strategically and beyond the immediate task. Key skills that you should work on developing as you complete your classes include the following:

• How to read quickly: This is how great scholars get anything done and why your professor assigns a high volume of readings. Why is this a key skill? Because even if you never pick up another scholarly book after your PhD, almost any professional position requires an ability to absorb knowledge quickly, and after absorbing six books per week for 12 weeks (okay, we hope we’re exaggerating here), reading a typical government or corporate report will be child’s play. As soon in your program as possible, you need to figure out how to master large volumes of knowledge efficiently. Focus on summaries, headings, and key points, and always be looking for the big picture: impact and influence in the discipline; how things connect or polarize. Come up with a note-taking system that works for you, and use it religiously.

• Oral communication: Professional positions inevitably place a premium on effective speaking, making presentations, and facilitating discussion, and there is no greater opportunity than a graduate course to build such skills. Nearly all courses come with one or more opportunities—and yes, they are opportunities, not curses—to do oral presentations, lead discussions, and participate effectively in group discussions. The more introverted you are (and many PhDs, including us, are at least partial introverts), the more you may cringe at this, but this is exactly the kind of focused, hopefully affirmative setting to build these vital skills. This includes both preparing impressive and appropriate presentations (and the bonus of getting accustomed to coping with technological breakdowns), verbally communicating your ideas, and facilitating discussion by guiding 10 opinionated grad students through a seminar.

• Research: Individual classes tend not to explicitly teach the methods and tools for gathering, organizing, and synthesizing large amounts of information, and students are expected to pick up this skill through experience and practice. That is certainly one option, but it is inefficient and risks leaving gaps in your knowledge. The good news: Most university libraries have highly developed research training sessions available to students and faculty. These sessions are worth your time, and you should seek these out as early in your program as possible because investments in this area will pay large dividends—including increasing your chances for success in your individual classes.

• Written communication: The scholarly world has a deeply deserved reputation for inaccessible writing. Graduate courses can even encourage this as students are forced to read through important but turgid work, leaving students with the erroneous impression that impenetrability is the key to great scholarship. We urge you to go the other way; even in graduate courses, well-written work gets noticed and gets better grades. Constantly seek to improve your writing, because this will benefit your career immeasurably. Good writing itself does not necessarily get you a job, but employers regularly lament that many or most prospective applicants can’t write well. There are untold writing resources available to you in bookstores, libraries, and online, and while we encourage you to read some of them, there are a few quick starting points that you should begin to employ immediately:

• Pay attention to the quality of writing whenever you read. Why is one author so much more engaging and effective than another? Look at what they do and see what you can emulate (e.g., short sentences are usually better than long ones). Absorb yourself in good non-academic writing— fiction or nonfiction—and some of it may rub off on you.

• Learn to structure your writing. Outline your work and what you are planning to say, then go back and fill in each part. Give yourself time to write in drafts. Have someone else read your work (and pick this someone else carefully). Always proofread.

• Kill passive voice—for heaven’s sake, kill that passive voice whenever possible! Shifting to active voice will increase the clarity of your ideas, and as a bonus your word counts will decrease, allowing more space for your ideas and presentation of supporting evidence. Review your work carefully on this front, and then rewrite everything in active voice unless you are making a conscious choice to keep passive voice for style and variety.

How do I select assignment topics within my classes to advance my future career?

We realize we are coming across as ultra-calculating at this point, and that it may seem like we will soon start telling you not to eat breakfast without linking each item to a career competency. (Not spilling food on yourself = professionalism …) But we can’t say enough about the value of thinking about how each part of your graduate program can help to work your career. This doesn’t mean every single move has to be part of a grand strategy, but it’s important to be alert and always looking for opportunities that fit into a larger plan. We’ve already talked about skill building in classes, but this also applies to assignment topics themselves. You are no longer an undergraduate, where what is written for the course stays in the course. Ask yourself: Can topics and assignments be linked to something broader so that they live beyond the last day of class and help you in the future?

The most obvious link is to your future dissertation—some assignments allow you to try out and develop ideas in an initial fashion that you might later use in your dissertation work. But other links may be future publishing goals—a course paper could be the foundation of a scholarly article—or some other way to provide clear evidence of a particular skill set, such as coming up with an original data set. Assignments might also give you skills in preparing for the comprehensive exams, especially overviews of the material, and indeed some grad courses are explicitly designed around this mission. Not all courses will give you opportunities like this, of course, but always be alert for possibilities. And eat whatever you want for breakfast.

How can I protect my mental health throughout my program?

Graduate school’s blend of intense work and unstructured solitary routines provides multiple potential points of stress across the coursework, comp, and dissertation stages. Individuals who flew through their undergraduate years may find themselves grappling with unfamiliar feelings of heightened stress and a sense of being truly overwhelmed, and some don’t fully recognize they are dealing with such feelings. Extenuating circumstances such as money or family issues may be additional factors. Be highly alert to your own wellness and actively seek activities and networks on or off campus that provide balance and support for your life. You likely have access to counselling centres and services that can help you, even if it’s just to check in and get an independent assessment of how you’re doing. It is critical that you prioritize your health and well-being.

Should I pick my dissertation topic and supervisor before I am done my coursework?

The PhD process looks very linear: complete classes, complete comprehensive exams, complete dissertation proposal, complete dissertation … completed. But what this model enjoys in simplicity it lacks in efficiency. The classes will take you one to two years, depending on your program. Add a good half-year or more to study for comps and only then, after two to three years, you start writing your dissertation. If your goal is to maximize the time you spend in graduate school this works well, but we suggest there might be a more expedient way.

While disciplinary and even institutional norms can vary, in the social sciences and humanities individuals are often admitted to PhD programs with a general topic and possible supervisor, but with no obligation to stick to them (assuming no specific promises or funding arrangements were made). Instead, students are free to roam the halls, looking for topics and supervisors that they ultimately feel are best suited for their goals. Unfortunately, this can result in indecision. It is possible—though in our view, highly inadvisable—for PhD students to still be unsure of a dissertation topic or even supervisor in their third or fourth year. It is understandable that, in the press of coursework and comps, making a final decision on the dissertation gets put off. And admittedly we warned earlier against deciding too early and showing up on the first day of the program with a rigid and inflexible plan of exactly what you want to study. But in our view, it is crucial to have at least a general idea by the end of your first year in the program at the very latest. It is okay to have lots of detail still to fill in, but you should be able to clearly answer the question “What is your dissertation about?” by then.

Of course, choosing a topic and supervisor should go hand in hand. We do not recommend coming up with a fully formed dissertation plan and only then looking for a supervisor’s name to add to the front page. Neither do we suggest deciding on Professor Brilliant without really having any idea what you want to do under his guidance. (Professor Brilliant doesn’t recommend it either.) Ultimately, while you have tremendous discretion in your dissertation topic, your choice of supervisor is (normally) limited to whoever is available in the program. Keep that in mind.

How do I select a dissertation topic?

All the large themes of this book come into play when developing a dissertation topic. Passion can be good, but not at the expense of practicality. It must be something that energizes you for the long run. It has to clearly be your choice, though with careful listening to others. It has to be firm but not inflexible. Above all else, it should be part of a larger general plan that has plenty of flexibility itself but takes you in the direction you want to go. While much of your deliberation will be discipline and field specific, we can offer a few guidelines here.

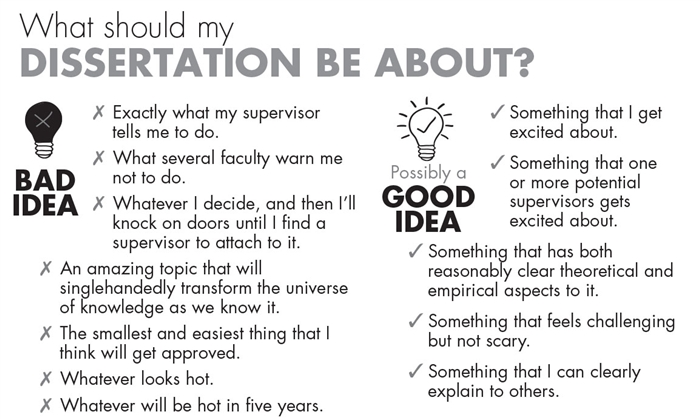

Figure 3.2: What should my dissertation be about?

A first but often overlooked step is to look at some recent finished dissertations—both in your specific field and perhaps more generally in your program. This may be daunting as you scroll through hundreds of pages (be it in the single monograph format adopted by many disciplines or the series of publishable papers format adopted by others) or explore examples of creative options such as an artistic work or visual presentation as permitted in some fields. As you consider recent works, look particularly at the overall question and themes, organizational structures, the methodology and scope of research, and so forth. These will likely vary, possibly to the point that you feel confused about what yours should look like. But looking at a few should give you some definite ideas of the parameters and expectations that should guide your unique project. And don’t feel daunted—these people finished their dissertations, didn’t they? So can you! (If you want. As we will say repeatedly in this chapter, there is no shame in stopping at any stage here.)

After you have done this, spend some time thinking about what energizes you. You need to balance topics that are of interest to potential future employers but also to you personally. There is an understandable tendency among PhD students to try to be strategic about their dissertation topic, by either choosing a subject that feels hot and in demand or steering away from what looks like an overcrowded area. We urge you not to overthink this, and particularly to avoid thinking that you can “time” the academic job market and pick an area that will be in demand when you finish. Trying to pick a field, much less a dissertation topic, with any real precision this way (“I predict that specialists on the Galápagos Islands are going to be in heavy demand in the next three to seven years”) is a very bad idea. Any truly consequential trends will be long term, with some areas in gradual decline and others rising, and there will always be some “staple” areas and skills that are in perpetual demand in both academic and non-academic organizations. Rather than trying to chase a hot area, play to your strengths and do what really interests you and where you can do your best work. Forecasting hiring markets, research grant parameters, and publishing trends with individual-level precision is almost impossible. What can be known, however, is that the dissertation requires a long, sustained period of attention to a topic, and therefore you must be interested in it.

We suggest that the ideal dissertation should modestly excite you—enough to keep you going, but not so much that you lose perspective (“This is going to change the world!”). It should feel challenging and like a stretch (if you are going to write about something you already know everything about, why are you in grad school?) but not scary. And it should be of at least modest interest to other people; if you cannot convincingly answer the “so what?” question, there is a problem.

Our experience: Jonathan

When I entered my PhD program in political science, I planned to write a dissertation on a recent government that I found very interesting. But over my first year, I heard several paper presentations and lots of talks that made me think everyone was doing studies on that exact topic, so I soon abandoned the idea. But almost none of that work ever emerged in print, and to date there has yet to be a scholarly publication anything close to what I had planned to do.

Okay, so let’s turn to figuring out your topic. Most dissertations in the social sciences and humanities are sparked by either a theoretical question or an empirical object of study. Developing the topic, then, commonly becomes a question of how to come up with the other. For example, you are fascinated by the question of how gender roles are constructed; now you need to come up with some empirical way of exploring this. Or, you are fascinated by youth crime rates as an object of study, but you need to come up with a theoretical question to guide your analysis. Stop and think: Are your ideas more about a theoretical question or an empirical phenomena? Have you managed to settle on one and are now trying to figure out the other?

Push yourself to be specific about what interests you. Here’s an example: Perhaps you want to study religious fundamentalism in some way relevant to your discipline. But what exactly about fundamentalism are you interested in? Are you looking at it primarily as a set of beliefs, as a social system, its external effects on society, or something else? Are your own views about fundamentalism relevant to the project? Those all affect your question. But they also affect your object of study: Which religions, and what qualifies as fundamentalism? How important is it to define who and who isn’t a fundamentalist? Does your focus include other orthodox groups? Nailing down these empirical parameters reopens theoretical questions about why you are looking at fundamentalism at all. It can become difficult to handle both aspects, and struggling simultaneously with the theoretical and empirical boundaries of a project is not unusual. We urge you to try and nail one of the two down while leaving the other more open, and then gradually try to bring them together as you move forward in your program.

When you are selecting a topic, practical considerations are also important and valid—especially family and financial ones. If you have kids, a year of remote fieldwork may simply not be an option. On the other hand, prepare to make sacrifices and stretch as far as you reasonably can. It’s okay to build your plan with options and variations that depend on finding additional funding; it’s also okay to make decisions on what is affordable and feasible, as long as you can intellectually justify it.

How do I find a supervisor?

The dissertation topic is only half the story; choosing a supervisor (and committee) to guide you is the other. The story ends happiest when both parts are woven together simultaneously.

The relationship between supervisors and students takes many forms, from Great Mentor and Lifelong Friend and Collaborator down to perfunctory but still effective. (We address ineffective relationships below.) Ultimately it is a professional relationship and should be approached that way. You want someone who will guide, prompt, and sometimes push you to excel. Your supervisor also wants something: a student and future peer who will energize them and make them do better in their own work as well.

As with choosing a dissertation topic, a little long-term strategizing can be good, but don’t overthink it. A big-name supervisor may open many future doors for you—research assistantships, references, employment opportunities, and so on. But not always. One of the most crushing disappointments of graduate school is finding out that the potential supervisor whose research interests perfectly match yours has a very different personality and working and thinking style than your own. Usually this can be navigated, but it takes time and effort from both sides. Alternatively, a lesser-known individual may be a terrific coach who really guides and stretches you to finish well, while Professor Big Name mainly communicates through garbled emails from airports. Again, there’s no firm rule here, though it’s quite possible you can build a separate relationship with Professor Big Name (such as having her on your committee) while working with a more attentive supervisor.

Given all of this, a little comparison shopping is fine here. Many, many PhD students end up with a great supervisor who they knew nothing about when they entered the program. (Recall what we said in chapter 2 about bench strength.) Coursework and talking to other grad students should give you an initial sense of individual faculty, and it is a good idea to make appointments with faculty to talk about your interests in brief, no-obligation conversations. Most won’t be offended if you keep shopping down the hall—and if they are, they probably wouldn’t have been a good supervisor. However, communicate clearly. Be open that you are looking for a supervisor and that you are still exploring options. And when you have decided, be sure to ask: “Will you be my dissertation supervisor?” You may get an equivocal answer at first, which is fine. However, some students fail to ask directly, just assuming that of course they will work with Professor Brilliant, while Professor Brilliant vaguely remembers a couple of hallway conversations with a student but can’t quite recall their name. Nail this down, or at least ensure it’s up to the potential supervisor to give an answer.

The supervisor is typically part of a committee (usually two or three other faculty) for your dissertation. Arrangements vary a lot here, depending on discipline and field, sometimes on university-specific requirements, but perhaps even more on personalities and unit size and culture. Some students work almost exclusively with their supervisor and the committee is not even formed until late in the process; others are more plugged into their entire committee from the start. The involvement of committee members will vary considerably, often based on personality and their level of interest in your work. Sometimes a committee member actually does more than the supervisor, especially if the latter is eminent and busy. Knowing all this is important as you look around. There is an excellent chance that you share close common research interests with Professor A, but actually feel a stronger connection and affinity to Professor B, who is less in your subfield but perhaps shares the same methodological approach as you. Or you might be interested in combining topics X and Y and have to choose between an expert in X or one in Y. Often a well-structured committee can help you straddle these choices. However, be alert for dynamics among committee members. It is unlikely that you will inadvertently ask two enemies who have sworn to never be in the same room together to serve on your committee, but you may have people with fundamentally different orientations who will pull you in different directions and can’t agree. The best way to avoid this is to ask your supervisor and committee members themselves for suggestions of additional committee members or run possible names by them. Their reactions will tell you what you need to know.

How do I know if I should continue my program after finishing the coursework?

This may seem like a strange question, even though we already warned you at the start that it was coming. Why would you do one to two years of coursework and then discontinue your program? Well, the reality is that for some students a few years of PhD coursework are all that is needed to satisfy their PhD itch. The fit between the program and their interests or personality just isn’t there, or a great opportunity has presented itself and continuing the PhD program would be a large opportunity cost. No matter the reason, there is no shame in stopping your PhD program at any stage, including after coursework. Let us say that again, because some people need to hear it multiple times: There is no shame whatsoever in stopping your PhD program at any stage.

Is the program energizing you, or draining you? Are you excited to start the next stage, or does it make you feel weary? Does the program seem like something you just need to get through, like a root canal or childbirth, or does it enliven you? You may have mixed answers, since every program will have high and low points and good and bad days. But ask yourself these two key questions: If someone handed you an exit degree in lieu of a PhD, would you happily take it and leave the program? And if you were forced to apply for the next stage of the program, would you make that application? Answer honestly and think about your responses.

These questions are doubly important if you did not receive strong grades in your coursework. The range of acceptable grades for graduate courses is much narrower than undergraduate courses, and failing or receiving a poor grade in any grad course is cause for serious reflection. While a single bad grade can be balanced by good performance in other courses, you need to reflect carefully on what caused it, how important the course is to your overall program, and whether it signifies a broader issue or gap that is likely to affect your future success in the program (e.g., you don’t like reading theory; you don’t like working with stats in a quantitative-oriented program). More than one bad grade is a real concern, as it truly suggests the program may not be right for you, and you may even be required to withdraw. But regardless, it is essential to think about gaps and problems evident in your course grades and whether or how they can be addressed before investing further time and energy into the PhD.

We are not going to tell anyone to stop their program. We are not going to tell anyone to continue their program, either. But we are going to encourage you to consciously make the choice about whether or not you continue your program. You are, as we stated earlier, your own agent and the person who should be acting in your own best interest. Take a pause between the key program stages to make sure that you are choosing to go forward, rather than just drifting along.

How much should I fear my comps?

Ah, comps. While they come in different forms, a fundamental stage in most PhD programs is the comprehensive exams (sometimes “qualifying exams,” “field exams,” etc.) whose purpose is to test your broad knowledge of the discipline or specific fields. Comps act as a filter: They are the most effective method available for PhD programs to identify individuals who have managed to get through their courses but are unlikely to succeed in the program and individuals who are drifting along, not asking themselves the previous question about whether they really should continue in their program. They are deliberately built as big walls—or at least, they seem big—that you have to get over.

We are sorry if that sounds scary, so read that last sentence again: They seem big. Comps take on legendary status in programs, looming bigger and bigger each week with an impending sense of doom. But it doesn’t need to be that way. A comp is just one more stage in the PhD program, and with good preparation you should be equipped to make it.

Comps typically come in two different models, usually varying by discipline:

• They decide: Here, the program identifies a comprehensive reading list, often based on field courses. Your job is to read it and be tested on it, usually on a common exam with a common grading committee. The bad news is that this means you have to read all sorts of things that you find marginal and irrelevant to your dissertation and interests. The good news is that you are likely doing this with others, all working off the same list. This provides great opportunities for study groups and support as you all complain about why you have to read this stuff.

• You decide: In this model, you are the primary designer of the comp, with the exam and committee customized for you. You may select from preapproved but smaller subfield lists, or you may construct your own reading list entirely, which is then approved by the program as the basis for your comprehensive exam. The good news is that it’s all tailored to your interests, your needs, and your strengths (or at least what you think they are). The bad news is twofold. One is the tendency to overdo things, constructing massive lists of what you think you should know and setting the bar too high for yourself; the second is that you will be studying for your customized comp by yourself, without peer support.

Some comps, especially in the “They Decide” model, are retrospective and based mostly on the field courses you just took; others, normally found under “You Decide,” are more prospective and tied to the specific dissertation topic and overseen by the dissertation supervisor. The number of comps you will have to do also varies: Two is typical, but there may be one or three or further subfield exams. They will vary in length of time, question format, and whether there is an oral component in addition to the written part.

Bottom line: Preparation is key here. Use your fear of comps to motivate yourself to be strategic as you prepare.

How do I prepare for my comps?

The best way is to read. The worst way is to … read. The difference, of course, is how you read, re-read, and process the information. We strongly recommend having a clear plan for comp preparation that goes beyond starting at the top of the reading list and going down.

Remember that a comp is just a big exam, and you’ve written a lot of exams by this point in your scholarly career. But one reason why PhD students approach comps with such trepidation is that in some cases they haven’t written a traditional sit-down exam in years. They feel rusty as they prepare for what feels like the biggest exam of their life. They have to scale up, and they aren’t sure how to do that.

To prepare for comps, think again about their purpose: They are about mastering knowledge. They are not meant to turn you into a walking library, able to instantly recall a couple hundred scholarly works in detail. But you should turn into a pretty good library catalogue—knowing what knowledge exists, how it is organized, and where it can be found. Think of yourself as a hawk, soaring above the forest of knowledge and seeing its broad parameters all clearly laid out before you. But with its amazing vision, the hawk can focus on one point and see the details. Similarly, studying for a comp involves both understanding and seeing the whole landscape, and then being able to focus and dive when needed. This is not as challenging as it sounds, provided you have a system, so organize your studying:

1. Rip apart the reading list into categories that make sense.

2. Set up a schedule that is realistic (which might involve some trial and error) but pressures you to keep moving, track progress, and check things off.

3. If you are fortunate enough to have others writing the same exam as you, form a study group. Groups provide a number of benefits, but the most important can be a division of labour, allowing everyone to take an area, read everything in detail, and report back.

Many programs share previous or mock comp exams, especially in the “They Decide” model, so go check immediately. Even if they don’t or you are in a “You Decide” model, ask individual faculty for examples and generally for as much information about the format and style of questions as you can get. Past questions may not be a perfect guide to the future, but they come close, and comp study groups typically and wisely spend time talking about how to answer them. Even more importantly, write answers to the questions and share them with your comp committee. As with eager undergraduates asking, “Can you look at my paper before I hand it in?” the committee may demur, but you may get some feedback.

More tricky to simulate is the oral component. This has become less common than it used to be, but remains in many programs, either as a mandatory component or as a second chance if the written exam is considered marginal. Again, research the format carefully here, but the most common is a follow-up a few days after the written exam where the examiners ask you to repeat and expand your answers. Ideally, this is a happy do-over where you get to be brilliant twice and have a meaningful intellectual discussion with your committee, but it can be a harrowing experience, especially if your written exam did not go well. Know your examiners, their particular interests and style of questioning, and what their expectations are for good performance in the exam. If you haven’t taken courses with them, ask to meet beforehand.

Comps are an ordeal, but slow and steady will usually win the race. Overconfidence and arrogance can be disastrous, but there is no need to lapse into imposter syndrome when you discover you can’t know everything about everything. In most cases, a looming comp failure can be seen coming, and the candidate has been told that there are concerns. That doesn’t mean a free pass for everyone else, but unless you are instructed otherwise, your program and your examiners believe you are capable of scaling the comp wall. Prove them right.

How do I know if I should continue my program after my comps?

Regardless of the outcome, after your comps you should pause and make a conscious decision about your next steps.

Program rules vary on what happens if you fail a comp; some will allow a second try, or it may mean automatic exit from the program (though be sure to know your rights regarding your ability to appeal a negative outcome). Failing a comp is serious business and is definitely a time to ask yourself again whether you should continue in your program. Recall again that comps are often the only point in a PhD program where the program can truly enforce quality control. Failure is definitely a signal that the program has serious doubts about your ability to succeed in your PhD. It is not a skill test that most people eventually master with a couple of tries and then all is well. Be frank with yourself: What happened? Can you identify clear reasons that can be corrected for next time, such as illness, misreading a key phrase, or temporary blanking on a crucial work? Resist the temptation to blame poor instructions, personal biases, or surprise formats, though admittedly those can be at play. The fact remains that a comp is meant to certify your basic command of the literature and ability to analyze it; it’s not an incremental process where practice will eventually make perfect. People do sometimes pass on a second try, but often they do not, for the same reasons as the first time.

But even if you did pass, take a moment. Programs may or may not give you much feedback on your comp performance. Ask for some, and ask people to be frank: Were there concerns? What were your strengths and weaknesses? You may not get much detailed feedback, but pay attention to whatever you do receive (especially if you get individual feedback from each examiner). It may be useful as you move ahead in your program and as you continue to identify and develop your key skills.

So regardless of how well you did in the comps, review again the earlier questions about whether you should continue in your program. Again, there is no shame in stopping your PhD program at any stage. You are, as we stated earlier, your own agent, and you are the person who should be acting in your own best interest.

How do I write a dissertation proposal?

Most programs require some sort of dissertation proposal stage, but the formality and expectations vary enormously. Your program may require a formal defence of the proposal, or it may only suggest it would be nice if you could write a few ideas down at some point. Sometimes it is the focus of a stand-alone thesis-preparation course. Regardless, the proposal will typically lay out your topic, your research question(s), your guiding thesis or argument, your literature review, your methodology and research design, and your planned chapters.

The aphorism “Plans are useless, but planning is indispensable” (usually attributed to World War II general and US President Dwight Eisenhower) applies here. The proposal is important, but not that important. It is primarily a way to focus and lay out your ideas and intentions as best you can; it is also an opportunity for your supervisor and committee to formally sign off on them and affirm that they think the project is doable. Yet dissertations may end up with little resemblance to the proposal that launched them for various good reasons. So don’t spend a year of your life formulating a proposal document and sweating over every comma. Ideally, the proposal and its various components will come fairly naturally as you develop your ideas. If there is a formal proposal defence, it may feel a bit harsh as it’s the one place your committee can really lay out their doubts. However, as with the dissertation defence, everyone wants (or at least should want) you to succeed. The proposal is just a proposal; it is not the dissertation itself. Treat it as a useful exercise to get you thinking clearly about what you will be doing.

How do I work effectively with my supervisor?

Supervisor–student relationships vary considerably and are often a function of personality and individual styles. Your supervisor may be a highly organized person with meticulous routines and schedules who expects you to fit into a monthly meeting slot they have set aside for you. Or you may be the highly organized person while your supervisor is brilliant but elusive and erratic. The onus is on you to adapt to their style. In any career path, “managing up” is a key skill. So figure out how to best manage your supervisor.

We will make one prediction: Your supervisor will emulate the way they were (or feel they were) supervised. There is no Supervisor School for them to learn how to supervise (though some universities may offer some general training and support), and the decentralized, free-range nature of most social science and humanities disciplines means supervisors often have only a vague sense of other models beyond their own experience. It is possible that there will be a close connection between your dissertation and your supervisor’s own research agenda; in this scenario, you may also be working as their research assistant, be part of a team with other PhD students or postdocs, or co-publishing with your supervisor. If this is the case, you will likely have a structured relationship with the potential for multiple points of regularized interaction. But the more common norm in humanities and most social sciences is the peripheral model: Your supervisor and you may have common interests, but your dissertation topic may have little relation to your supervisor’s own agenda and projects, and co-publishing or other collaborations are unusual. The relationship is far less structured (“go away and think; come back when you have something”), allowing for more independence but great perils of neglect; out of sight, out of mind.

In either model, your supervisor is also distracted. You are likely not the only graduate student they are overseeing, and they have their own teaching, research, and service responsibilities. As you are your own agent, you need to take leadership to make sure you stay on the radar and to ensure your supervisor knows your needs, especially in the peripheral model where the natural inclination is to leave you alone. The best and oft-prescribed solution, especially in the initial stages of the dissertation, is to set weekly or monthly meetings that force both of you to check in with each other. However, this schedule is likely to fade over time as you get deeper into the project and have less to update, one of you vanishes for a time on fieldwork or sabbatical, or you move to a different city entirely, so you may need to find new and more creative ways to maintain the relationship. But take initiative to ensure there is a structured pattern of interaction; do not assume your supervisor will do so.

While ideally your supervisor and you will mutually adapt and form a good relationship, unfortunately sometimes things don’t go so well. This poses all kinds of challenges, and most crucially the dilemma of discerning when things are beyond repair (see Table 3.1 for thoughts on that front). Our biggest advice is to discreetly talk to others, particularly the graduate or department chair. Do not suffer in silence or feel you have no options in a difficult supervisor relationship. Talking to others will help you gain perspective and understand your options. The supervisory committee can be important here, compensating for the deficiencies of the supervisor—though if you find your whole committee to be against you it may be a sign that your supervisor isn’t the problem. Be self-reflective, and above all maximize your agency to address the situation as soon as possible.

Table 3.1 Addressing student–supervisor relationship issues

Problem |

Supervisor-Caused |

Student-Caused |

Solution |

Beyond Repair? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Poor communication |

Your supervisor is unavailable, physically and/or intellectually. You get little or no feedback or direction. |

You are in touch erratically and unpredictably. You send work to your supervisor “out of nowhere,” often with pleas for quick feedback. |

- Schedule regular interactions - Establish fixed dates for sending work and reasonable deadlines for responses - Consider looking to your committee for more direction |

Usually can be salvaged, especially with a supportive committee. But if patterns recur over and over and your supervisor is out of touch for long periods repeatedly, speak to your grad chair about alternative options. |

Contradictory/ ignored advice |

Your supervisor tells you different things at different times. |

You repeatedly do things your supervisor advised you against or don’t do things they advised you to do. |

- Document discussions in writing - Follow up on verbal meetings with memos: “As instructed by you, I am doing the following …” - Seek clarity in instructions, even to the point of bluntness |

Can sometimes be corrected by better communication of assumptions and expectations. But if your supervisor’s vacillations lead to repeated wild-goose chases or junking large chunks of work, it is time for a change. |

Personal dislike |

You and/or your supervisor increasingly dislike interacting with the other. |

- Minimize personal interaction and shift to written communication - Document problems in case of further breakdown/abuse |

The relationship can usually continue, though through gritted teeth. A loss of basic civility and professional behaviour indicates a need for change. |

|

Mutual breakdown |

Your supervisor and you are on fundamentally different wavelengths and cannot agree on what basic aspects of the dissertation should look like. |

- Agree to disagree - Request assistance from the graduate chair to find a solution |

While not ideal, agreeing to disagree can work. If you cannot find a new supervisor, that may be a sign that your subject needs to be revised. |

|

Abuse |

Your supervisor exploits you personally or intellectually. This may extend to sexual harassment or stealing research and publication credit. |

- Know your rights - Create written documentation of any concerns or incidents; if something is bugging you, write it down for later reference/evidence - Do not be afraid to report abuse in confidence to university authorities |

If you don’t trust your supervisor, ask the grad chair to assign you a new one. |

|

How can I progress through my dissertation? (Or, “how will I ever get this done?”)

Your proposal is done and approved. Now you just have to write the dissertation, right? Well …

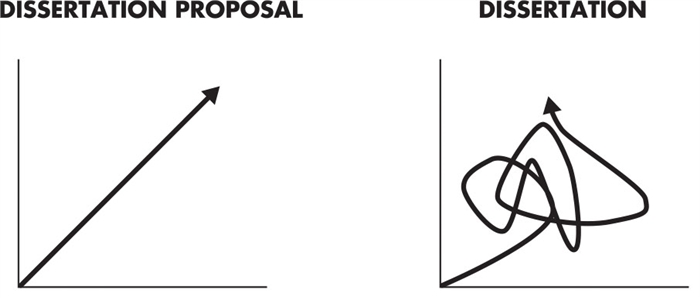

No matter how much you have prepared and planned, the dissertation will have twists and turns you never anticipated, numerous potholes, and possibly giant gaps looming in the road ahead. Some of these may seem disastrous, but nearly all can be navigated and overcome. As we said, the dissertation proposal is rarely a perfect roadmap. But it gives you direction and an initial plan.

The twists, turns, and gaps will take many forms. Empirical data turn out to be unavailable or useless. Theoretical approaches lead you into blind alleys. Access to sources is 10 times harder or takes 10 times longer than anticipated. Travel funding falls through. Your language studies suggest you were born to remain unilingual. You find yourself arguing against your initial thesis. And things just generally don’t go as you planned. We realize this may sound scary, but our message once again is this is normal. Few dissertations proceed absolutely smoothly and most encounter significant challenges. The good news—though perhaps not consoling when, say, the archive you were counting on burns down—is that overcoming these challenges usually makes the dissertation better and makes you better. This is the core of the PhD program: not the coursework, not the comps, but pulling off a major intellectual project that no one has done before. An important part of this—and the sign of a mature career professional who is no longer a student—is adapting to circumstances and forging ahead when there is no well-marked trail. You can do it.

Figure 3.3: Dissertation proposal vs. dissertation (idea adapted from Demetri Martin).

Some challenges will be common to almost all PhD candidates, while others will be specific to your project and will often be different by discipline or field. Even the common challenges may require different solutions that suit your circumstances—this is what your supervisor, committee, other faculty, mentors, fellow students, and any other wise people you know are for. Admittedly, it’s then an extra challenge to know how to weigh their advice, especially when it conflicts, and sometimes they will have none to offer (“Gosh, that’s a toughie. I don’t know”) or it’s even just wrong (“Don’t worry about getting turned down by the ethics board; just go ahead anyway”). But this is part of the discernment process as you move from student to career professional; your professors no longer have an answer key or rubric hidden away in their desk. They can give you guidance, but ultimately the creativity and solutions are up to you. And again: You can do it.

Recognize also that you will never feel you have enough. There will always be more scholarly literature to read, more cases to examine, more data to gather, more theories and concepts to consider, more examples to give in this list … While you likely struggled with this already as you formulated your topic and drafted your proposal, it will continue throughout the dissertation. Learning how to set both theoretical and empirical boundaries is important, especially if your initial carefully thought-out parameters aren’t working in practice. In most cases, you will be your own worst enemy, while your supervisor and others can cast a more objective eye and let you know that it might be time to stop. On the other hand, if they are pushing you to go further and do more, they are probably right (though see the discussion on discernment in the paragraph above).

Perfectionism can be a huge problem for many dissertations (and scholars at all levels). Sometimes this is about the fear of missing something (“I’d better review my notes for the 124th time”), but other times it’s about perpetual improvement (“I just know I can say more here …”). Avoiding error and improving are both good things, but as with never feeling you have enough, you have to figure out where to draw the line. This doesn’t mean settling for mediocre work. But sometimes it means doing what you can, and then going back to revise and improve later.

As you progress with your dissertation, pay careful attention to ensuring your work meets the standards of trust inherent within academia. As a PhD, you presumably know basic rules of academic integrity. But as you move from student to scholar and career professional, the issues and ethical questions may seem greyer. While there is more and more emphasis on disclosing and verifying data, sometimes you may be tempted to do “little” things (“If I just clean up the language in this quotation a little, it will get the point across much better”). Never forget that your reputation depends heavily on being able to see the ethical lines and stay well away from them. Whenever in doubt, seek advice.

It can take a long time to feel you are getting anywhere in your dissertation. It may feel like standing by a pond, throwing pebbles into the water. Each pebble disappears, but if you are throwing them accurately, a pile is building up underwater out of sight that will eventually emerge. Now obviously we think your dissertation is more purposeful and constructive than throwing pebbles in a pond, but the point is to remember that things can still be building even if you can’t really see them yet.

How do I know if I should continue my program during the dissertation stage?

Unlike after completing courses and comps, there is no natural moment in the dissertation stage where you can pause and reassess whether you should continue in the program. However, there will certainly be moments—possibly many, many moments—where you will wrestle with this question, especially each year that you re-register and possibly pay hefty new fees. We’ll say it again: There is no shame in stopping your PhD program at any stage. You are, we repeat, your own agent and the person who should be acting in your own best interest. At a certain point, it really may be best to stop throwing pebbles in the pond and move on.

But determining this point is very hard. No one avoids significant ups and downs in the dissertation, and there will undoubtedly be times when you can’t stand to even think about it. (We know of one case—not us—where after the defence the student literally set fire to a copy of her dissertation and danced around the burning embers.) It is hard to distinguish between periods of discouragement and the time to leave.

Mental health challenges are common at all stages of education and in society generally, but can be particularly acute during this stressful period. Depression and other conditions may manifest themselves, and the social isolation of completing a dissertation makes it even more difficult for you and others to understand they are more than the usual ups and downs. We strongly urge you to find supportive people who can help you recognize how you are doing mentally and emotionally and to seek help without hesitation.

Even setting aside depression and other challenges, in any PhD there is a chance of an abyss, a time, usually near the end of the dissertation writing stage, when things seem particularly hopeless. The dissertation may seem to be a dead end that will never be finished, and you may feel alone and disoriented, wondering if you are going in the right direction and whether you will ever finish. Not everyone will experience an abyss, thankfully, but if they do, it is the most likely to shake their confidence that any of this was a good idea and certainly whether they should keep going.

Again, ask the questions we presented earlier. On balance, is your dissertation energizing you, or draining you? Most days, are you excited about it, or does it make you feel weary? Do you at least see some light at the end of the tunnel? Or are you just metaphorically closing your eyes and trying to endure it like a root canal? And if someone handed you an exit degree now, would you happily take it and leave? Some programs after a certain stage do require PhD students to formally apply each year to continue in their program. It is often treated perfunctorily, but we urge you to think very carefully about it. Do you really want to reapply? Or is it time to go? Answer honestly and think about your responses.

Take care of yourself, seek the help of counsellors and trusted others as needed, and give yourself permission to consider all options. Trust your instincts and direction, along with the advice and support of your committee and others. Be confident that you can climb out of the abyss, but also be realistic about whether it is worth the time and effort. In a PhD program, and especially at the dissertation stage, doubts are normal and problems are to be expected. Sometimes it is best to stay, and sometimes it is best to go. Be proud to choose either option.

Our experience: Loleen

I recall my abyss moment (which lasted a few weeks) very well. I was two-thirds completed my dissertation and just did not care about it anymore. A lot of my thinking was reflective of personal factors: I was living in another country with no social support network nearby, and while the university at which I was a visiting scholar provided me with office space, I was choosing to work from my apartment under the assumption that it would be more efficient. (The reality was that it was just socially isolating.) I decided to explore other career options and called a consultant that I found in the yellow pages. (Yes, it was the 1990s.) In that phone call, this kind gentleman asked enough questions—and the right questions—to make me realize I did want to finish my PhD. I have always been grateful to him for speaking to me. And he never charged me a cent.

Can I use a copy editor or a statistical consultant for my work?

A tricky issue for dissertations is whether the student can engage professional help, such as a copy editor or statistical consultant, to “polish” the final product. Practices vary wildly, and your institution and program may or may not provide any automatic guidance here (check your program guidelines/handbook). Some disciplines, programs, and supervisors may find this perfectly acceptable and normal, while others are appalled by the idea. We confess to being closer to the latter—after all, this is a piece of academic work and you are being assessed on it as its sole author, so the idea of hiring someone to help with parts of it is concerning. On the other hand, no dissertation is written without specific advice and multiple reviews with marginal notes and corrections from your supervisor and committee, academics regularly review each other’s work, and copy editing is a customary stage for academic publications. Thus, it is a bit disingenuous to claim that mature academic work is ever written without at least some help.

Certainly any professional help should be fully disclosed to your committee. And what concerns us and most programs is when the assistance goes beyond a passive cleanup of small errors to active rewriting or recalculating. Hiring someone to turn poorly constructed academic work into something passable is not, in our view, acceptable. Seek careful guidance from your supervisor and program on these matters prior to seeking out professional assistance; if they are appalled or seem even slightly uncomfortable, you have your answer.

How do I know when my dissertation is done?

We’ve covered a lot of ground, but an important question remains: What exactly makes a dissertation? And who decides when it is done? This is a difficult question to answer, but one you will likely ask as your supervisor says “just one more draft and that might be it.” Your dissertation proposal surely set out some goals and objectives, but determining exactly when they have been met, especially after all the additional twists and turns, can be a challenge.

Even within your discipline or field, there is likely no easy standard for determining when a dissertation is sufficient to go to defence. This is partly because each one is a unique project that is difficult to compare against a set benchmark. But it is also a function of what purpose(s) your particular dissertation is meant to serve in relation to your own future plans and goals.

The escalation of publishing expectations in academia means there is tremendous demand to treat a dissertation as immediately publishable upon completion. But “completed” and “publishable” are not the same thing (except in certain programs that expressly set this standard, especially with the multiple-paper option). Historically, many dissertations were not published at all, or only after years of revision. But now, many supervisors and committees see their role—really, their duty—as pushing you to not just “complete” the dissertation, but to produce a publishable product that will give you a fighting chance on the academic job market. You need to decide if it’s the standard you want to follow. That’s not to say the alternative is “no standard.” But many dissertations are coherent, original, and well-deserving of a PhD, but are also lumpy, disproportionate, detailed but extremely narrow, or otherwise unlikely to satisfy a publisher or set of journal editors. If you feel that is good enough to suit your future goals, tell your supervisor and committee and ask if they agree.

Supervisors in turn may be somewhat unsure when to declare your quest over, because they are waiting to see how far they can push you. A good supervisor has been coaching you to excel all along, and they want you to be the best you can be. So they may set what seems to be a higher standard for you, because they think you can achieve it. Alternatively—and let’s be frank—sometimes dissertations are passed with committees holding their noses. This is when the student has hit some kind of bare minimum and the committee feels they can push the student no further; they made it, though they are unlikely to go further in the academic world. But they’re still a doctor of philosophy.

What should I expect for the dissertation defence?

Most PhD programs in Canada have long relied on an oral defence of the dissertation as the final stage of the doctoral program, though there are alternative models such as a written external review that determines whether the dissertation is passable. The lineup varies but typically includes an external examiner from another university, your supervisor and committee, and at least one or two other faculty examiners. In some programs, the defence is a public event—all your fellow PhD students will come watch. In others, it is much more of a closed affair. Some defences are extremely formal (possibly the only time in your program that you’re addressed as “Ms.” or “Mr.” or see your supervisor in a suit) while others are surprisingly relaxed (“Hey, Joe and Linda—which one of you wants to ask the next question?”). You may receive the examiner’s report before the defence, or it may be kept top secret. Rules and norms here will vary widely.

To non-academics, the dissertation defence may seem like the toughest stage of all—having to defend your work in front of five, six, or more professors! What a test of fire! But while programs and disciplines will vary, the dissertation defence is generally not meant to be a firing squad where the examiners blast away and see if the candidate survives. In most cases, it is more of a final flourish, but with an immense amount of preparatory work beforehand.

Our biggest tip: Ask about the procedures, especially if you haven’t had opportunities to watch previous defences. Know what to expect. Take advice on whether and how to make an opening statement, use of technology, and approximately how long it will take (and when and how long you will be asked to leave the room while the committee deliberates). In short, control the stuff you can control.

Ideally, a defence is primarily a conversation about the academic merit and acceptability of your work. Some of the questions may be tough, and it’s always wise to prepare for a real grilling since the examiners will feel a duty to be as rigorous as they can be. But—again, ideally—the dissertation and you have been well prepared and can withstand their slings and arrows. Your program, and especially your supervisor, should not let you walk into the room unless they are confident you can succeed. And the external examiner should be chosen carefully, as someone who has standing and independent judgment but is not going to be excessively narrow, impossible to please, or arbitrary and petty.

Remember one very important fact in the defence: It is not about the field or topic like a comprehensive exam, but specifically about the dissertation. And who is the expert on your dissertation? You are, of course, and you know it far more deeply than anyone else in the room. Prepare well by reviewing it (we guarantee you will occasionally pause and ask, “What was I thinking when I wrote that?”) and all the comments from your supervisor and committee. Anticipate lines of questioning and sketch out responses, though there is no need to memorize a script. Your real answers in the defence should be natural and based on your underlying command of the material. Try and think of 10 really tough questions and how you will handle them—and then relax when most of them don’t even come up in the defence. In fact, examiners, especially if they are later in the question order, may even feel stuck for questions (“Hey! The external examiner asked all the methodology questions I was planning!”) and may use up their time with long comments or speculative questions (“Tell me, how would your study of 1970s disco be different if John F. Kennedy hadn’t been assassinated?”)

Sometimes things aren’t so ideal. The supervisor and program haven’t prepared you well. An examiner goes ballistic because you don’t mention a particular body of literature. A committee member suddenly decides now is the time to bring up a major concern they’ve sat on for two years. But while these can be harrowing experiences, the worst-case scenario in such situations is rarely failure but passing with significant revisions—new pages or even an entire chapter (but almost always closer to the former than the latter). This means more work, but unlike all your other dissertation efforts, this one should have clear instructions and a clear finish line. The true worst-case scenario is when the dissertation is not ready but the defence takes place anyway at the insistence of the student against the advice of the supervisor. Typically the relationship between the two has broken down, but sometimes students push the defence because of financial or personal pressures, especially at the end of the academic year. The result may not be pretty, and at best will probably be the nose-holding scenario mentioned above. Don’t be that student.

And now you’re almost done. You are waiting out in the hall while the committee deliberates (or, quite possibly, is just trying to figure out how to fill in the paperwork). This may take a while and be a painful wait, but eventually they will invite you back in. There is a good chance they may ask for some minor revisions and corrections, and a smaller possibility of major ones as described above. But … that’s it! You did it! You have a PhD! Congratulations!

I am well into my program and didn’t do any of this. What can I do now?

There is no perfect student who does every aspect of their program “ideally,” and even if one existed, no one would like them very much. But no matter what stage you are at, you have choices and agency. You can take ownership of where you are now and make whatever adjustments are within your scope of action or influence. And chances are good that you have done at least some of what we describe in this chapter. Start by creating a grid of the career competencies listed in chapter 1. What career competency areas were covered by your coursework? By what you did for your comps? By what you are doing for your dissertation? Where are there gaps? If you can spot areas of truly absent competencies, what resources are available to you as a grad student that you can take advantage of? Above all else, be sure to give yourself credit for the strengths you have developed and the good choices you have made. You made the best decisions you could with the information you had at the time. Now, after reading this book and reflecting more on your experience, you have more information to inform your future decisions. Use it.

So, how can I work my program?

Throughout this chapter, we have returned repeatedly to the idea of personal agency: that you are continually making choices. At each stage, we of course hope that you will return to our guiding question: Given both my future goals and the information currently available to me, what is my best decision right now? While your future goals may remain relatively consistent (and again, we suggested that your future goals should include a successful, rewarding career that uses your talents and the skills you developed over your education), the information currently available will change over time. As you proceed in your program, the knowledge—dare we say wisdom—that you acquire will grow, and your choices will become more nuanced and informed. And at each step, you get to make choices. It is your program, and your life, and no one is going to care about it as much as you do and will. By consciously making the key decisions over your program that align your actions with your goals, you will be doing everything you can to work your program and your career.

Nice Mr. Clarke from kindergarten would be proud of you. And even if he isn’t, we are.