Chapter 2 Select Your Program Carefully

The children’s Choose Your Own Adventure book series speaks to the dilemmas inherent in making choices. Given a small amount of information, the reader makes a choice, directing them to another section of the book with another small amount of information and another choice. Sections lead to choices, leading to more sections and more choices. At the end, based on the preceding choices, the reader winds up victorious, or not. Contemplating if and where to do a PhD can feel equally fraught. There are so many options, and among those, presumably, is an option or set of options that is right for you and your needs, and another set that is not so good a fit. And your choices, ultimately, can have significant consequences for your overall life in terms of what you learn, who you meet, how much time and money you invest, and your future career prospects.

Have we caused you a small anxiety attack? Fear not! Selecting your program is a perfect place to start applying our question: Given both my future goals and the information currently available to me, what is my best decision right now? Like the adventure book reader, you must make hard choices, but unlike that reader you have the agency to increase your information before doing so. The trick is to know what information you need and how to assess it to make your best decision right now. So let’s get to it.

Should I bother reading this chapter if I am already in a PhD program?

There is inherent risk in reading about decisions that one has already made and cannot undo. While you could read everything we have to say in this chapter and think, “Great! I did everything right,” some or all of what we have to say may run entirely contrary to choices you have already made, which presents you with an unhappy dilemma: You can either accept our positions and feel bad about your choices (Terrible Option A) or reject our positions and decide this book is complete bunk (Terrible Option B).

We suggest instead Happy Option C: Use this chapter to identify the strengths of your existing decisions so that you can build on these, and to be aware of their limitations so you can proactively bridge or work around them. Ultimately, choices about grad school are less about truly good or bad decisions. Like most things in life, it’s more about making the best set of decisions you can … and then making the best of the decisions you made.

How do I decide if a PhD is right for me?

Give careful thought to why you want a PhD and what you hope to get out of it. As much as we emphasize career planning here and throughout the book, choosing to go to grad school ultimately needs to be first and foremost an intellectual decision—you want to pursue knowledge further. If you don’t crave knowledge and its pursuit, you’ve got a hellish few years ahead (as does your potential supervisor) before you likely drop out. Only that craving for knowledge is going to get you through courses, comprehensive exams (“comps”), and your dissertation.

Beyond a thirst for knowledge, though, you should ideally have a career motivation, and this career motivation should be broad in scope. Many students enter programs with clear or vague aspirations for academic careers, but as we discussed in chapter 1, the long-standing uncertainties of the academic job market mean that it is a good idea to not put all your eggs and hopes in one basket. We encourage you to consider not applying until you can envisage a number of possible career outcomes, of which “professor” is only one. We should note a particular word of caution to readers who don’t really love research and are considering pursuing a PhD purely with the goal of teaching at the university level: We address this more fully in chapter 9, but all university faculty positions, even many or most teaching-focused jobs, carry expectations for research and scholarly publications; if the fire in your belly for research is even somewhat low at the start of your program, your postsecondary teaching dream has a high probability of being realized only in the form of the “sessional trap” (see chapter 8) of teaching individual courses with low pay and limited job security.

Should you pursue a PhD to obtain specific career skills? We discussed career competencies in chapter 1, and in later chapters we will discuss how you can strategically approach your program (chapter 3) and non-program (chapter 4) activities to build these competencies, and how you can communicate these to potential employers (chapter 8). But an important question to ask yourself is this: How will the skills you develop and deepen during your PhD go beyond what you have already developed in your bachelor’s and master’s degrees? As we wrote in chapter 1, we suggest that your goal should be a successful, rewarding career that uses your talents and the skills you developed throughout your education; it is possible that you already have the education you need to do what you want to do in life. Ideally, your time in a doctoral program will build skills of complexity, depth, and scale that are distinctly different from those of your earlier degrees. If you cannot see a clear path to do so, the considerable time and financial investment in a PhD program becomes more questionable.

You will notice that we do not mention the word “passion” in the decision to pursue a PhD. This is because it is critical to emphasize the practical here. What are the practical reasons why you want to complete a PhD? Unless you are financially independent or have no interest in building a professional career, you need some answers. While a master’s degree is an acceptable way to bide time while you decide what to do with your life, the PhD takes up far too much time and money (and leads to such uncertain career options) for anyone to wander in solely to follow a passion. It needs to be part of a plan for your life. The plan can be fuzzy with lots of possible options—in fact, it should be fuzzy with lots of options. But you should still have one.

A final point is directed at mature students who have been out of school for a while and have perhaps enjoyed some professional success, started a family, acquired a mortgage, dog, snow tires, and so forth and are considering returning to do a PhD. Our message is simple: Good for you for considering something new, but take all our advice to think carefully and double it. It is entirely possible that acquiring a PhD may be exactly what you need to move your career and professional goals ahead. Just look before you leap.

Here are some basic facts to keep in mind as you weigh your decision:

1. You don’t need a PhD for almost all non-academic jobs.

2. While you do need a PhD for almost all academic jobs, those jobs are few (and possibly decreasing) in number, and pursuing a PhD solely for the purpose of securing that specific type of job is risky.

3. PhD programs remove you from the workforce for a number of years, and you lose earnings and earnings growth during that period. The available data suggest that you will make those earnings up over time, but not in a huge way. During that time, you will likely be living like a grad student while your friends are buying their first homes.

4. For many people, the doctoral study stage of life overlaps with the prime family building time of life. Frankly, having kids is challenging at the best of times. Studying for comprehensive exams or conducting ethnographic fieldwork is, arguably, not the best of times.

5. PhDs always take longer than anticipated. While four years is widely bandied about as the “program length,” average completion times in the social sciences and humanities can be six years or more, because dissertations take a long time. Completing in four years is unusual.

6. Being part of a PhD program can be intellectually thrilling. There is a reason that it is a life goal for so many people.

7. In completing a PhD, you will develop a number of competencies that are relevant to and valued across a number of careers. (This book will help you do so more clearly and efficiently.) At the same time, a PhD is not the only way to develop these competencies, and it may not be the most efficient way to do so.

8. Having a completed PhD is highly satisfying. True, some family members may occasionally refer to the fact that you “aren’t a real doctor,” but it is a large accomplishment that you will be proud of.

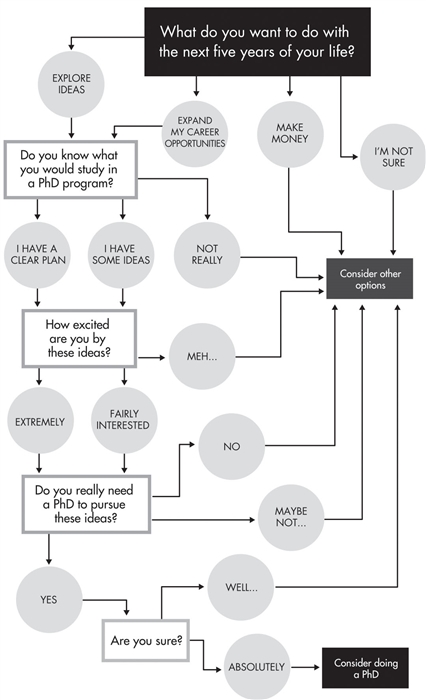

In case anything wasn’t clear, use our handy decision tree (Figure 2.1) to decide if a PhD is right for you.

Figure 2.1: Should you do a PhD?

Still interested in doing a PhD? Read on.

How do I decide which programs to apply to?

It’s remarkable how many aspiring academic researchers do little or flawed research when applying to doctoral programs. Pity your authors here, who in the early 1990s had to do all their program research on paper, looking up addresses and sending snail mail inquiries for brochures. In the online age, the dilemma is working through the cascade of options, so we’ll have some pity for you, too. There are so many choices. How do you even decide where to apply (and send your application fee)?

As we said, you need to approach grad school with a plan—a plan that has some options. With that in mind, you can start thinking about initial parameters to consider when sorting through programs.

• Canadian vs. international: PhD programs are different in each country, and prospective students do not always realize this until they show up. Coursework is typically more extensive and longer in American PhD programs, where it is standard to admit students directly from the bachelor’s program. At the other end of the spectrum, British and Australian PhDs traditionally have no coursework at all, throwing students immediately into the dissertation (although some have introduced coursework and comprehensive exam requirements). Canadian PhDs are in the middle: shorter with less intensive training than American programs, but longer with more preparation than British and Australian ones. And that’s just the start of national variations. All of these can be great choices—just keep the basic distinctions in mind as you do your research.

• Broad vs. specialized program: Doctoral programs are becoming ever more specialized and niched, meaning somewhere there is a program that probably exactly matches your interests—at least, your current interests. It’s obviously exciting to think, “This is exactly what I want!” But there are two risks here: (1) your interests can change, and (2) getting too specialized too early means you might not realize your interests have changed, and then wonder why you feel increasingly trapped and miserable. In contrast, a broad, disciplinary-wide program gives you more options and freedom to grow … grow, or flounder, that is. Give careful thought to which is best for your career aspirations: A specialized program may lead directly into a related professional field, while a broad program allows more flexibility and a chance to grow and adapt in new directions.

• Big or small: Small PhD programs usually mean more faculty attention and a more intimate community, often around shared interests. Large programs have a richer selection of faculty and colleagues. Your fellow PhD program travellers are important here, as they have the potential to be important connections both while you are completing the program and in the decades that follow. Some will be future key professional contacts, working in industry, government, academia, and the not-for-profit sector; some will be future lifelong friends or nemeses. Small programs will naturally have smaller student cohorts (in some cases tiny cohorts), which can mean fewer contacts but the potential for tighter bonds; the reverse is true for larger programs, though you’re then not stuck with the same three people for the next 4+ years.

• Academic vs. professional: Doctoral programs fall into three (sometimes overlapping) categories: traditional disciplinary PhDs, interdisciplinary programs, and professional doctorates that explicitly or implicitly market themselves as being for people aspiring to non-academic careers. Most universities offer a mix of these with varying degrees of overlap (e.g., professional programs are also likely to bill themselves as interdisciplinary, and faculty may teach and supervise in more than one program). The traditional appeal of the disciplinary programs is that they prepare people in depth for strong academic careers in the core of the discipline; the knock against them is that this is the only thing they tend to do. Interdisciplinary programs are argued to be more innovative; a downside here is that graduates who are interested in academic jobs struggle to position themselves since they don’t quite fit in several different disciplines at once and academic hiring committees often want candidates that can teach broad disciplinary courses.

For many, the big question is between the academic and the professional programs, with a fear that choosing one cuts off opportunities in the other. The good news is that this is mostly not true: Universities sometimes hire people with professional PhDs, and individuals with academic PhDs flourish in a wide range of sectors. It mostly depends on what you actually do in the PhD—the breadth, depth, and skills you acquire and how you position yourself, which is what this book is all about. If one option strongly resonates with you, go for it. Having said that, traditional academic disciplinary PhDs are the normal default choice.

Table 2.1 Thinking through program options

Pros |

Cons |

|

|---|---|---|

Canadian |

Canada! Possibly close to family. |

Canada. Possibly close to family. |

International |

Opportunity to live in another country and gain international experience. Lifetime ability to casually drop comments like “When I was living in Geneva” into conversations. |

Over time, living far from your support network may be isolating, and travelling home can be expensive. You might even grow to miss Aunt Hilda. |

Broad |

Possible to explore a variety of interests and connect in many directions. A feast of knowledge. So many ways to grow. |

Everyone does their own thing in different directions. No one really seems to understand your work. You might feel alone in the crowd. |

Specialized |

Can address your particular interests, and allows you to spend years with people who are similarly obsessed with a particular niche area. |

Your particular interests can change, and the narrow discussions may prove aggravating over time. You may grow to hate the destiny you chose for yourself. |

Big |

Larger pool of peers and future contacts (networking, right from the start!). Lots of different people and groups. |

Sometimes can be a competitive and complex environment where you have to fight for attention. |

Small |

Potential for a tightly knit cohort and more individual attention from your supervisor and other faculty. |

The same small group of people … for 4+ years … |

Academic |

Go deeper and further intellectually than at any other time in your life; clearest pathway to a potential academic career. |

If you’re not careful and don’t keep your options open, this pathway could lead to a difficult career transition period. |

Professional |

More applied training, with an emphasis on specific skills for a non-academic career. Your program may even make sense to family and friends outside academia. |

The risk of a credential that does not carry depth and weight to justify the years invested, with skills that might have been learned elsewhere. A lot of time, money, and work just to get some letters on your business card. |

Having formed a general idea of what sort of programs you are drawn to, you can now sort through which programs to apply to. Here are some things that might influence your decision:

• Name brand: Prestigious universities have many strengths—international recognition, deep pools of eminent faculty, fat endowments, and so forth. These can all be good for your grad school and long-term career. On the other hand, prestigious universities can be coasting on their reputations or be such vast operations loaded with egos that there’s little time or attention for lowly grad students. They also sometimes offer less funding, since they feel less pressure to compete for students.

• Bigshot name: You dream of going to University X to study under the great Professor Y. Nothing wrong with that, and ideally it will be a life-changing experience. But sometimes the dream is rudely crushed. The great scholar may be so busy and overloaded that they barely learn your name, with supervision effectively delegated to a subordinate. And you may discover that the great thinker has an odious personality.

• Bench strength: Whether or not there is a Mighty Famous Bigshot, you need to also look at the rest of the faculty in the program. (Be sure to distinguish between different programs on the same campus.) Are there names you recognize or whose research areas look interesting? You want to be sure this is a place where you can feel at home and form a strong supervision committee. Beware again of the above perils of big names, as once you arrive you may well discover a wise mentor who you didn’t initially notice. But a good rule of thumb is that if you don’t get excited scrolling through the list of program faculty and their interests, the program is not for you. As we discuss in chapter 3, in social science and humanities disciplines students are often admitted into the program as a whole, then set loose to wander up and down the halls to find a supervisor. (Sort of.) Given this, you want to have a reasonably target-rich environment. This doesn’t necessarily mean a long list in your specific subfield, which may indeed just have a couple of people. But they should be backed up by others who can also be of use to you.

• Program requirements: While the formats of social science and humanities PhD programs are common enough that we’ve gone ahead and written this book about them, there can be significant differences even within the same discipline, and even more for interdisciplinary programs. Research these as much as you can, such as what courses are required and how comprehensive exams work. Admittedly, it may be difficult to know what to do with this information, especially if you’re just reading it off the program website with no insider knowledge. However, you may come across important or striking things that affect your choices or encourage you to make direct inquiries to the program (“Is it true that every doctoral student has to learn three languages to pass their comps?”).

• Past degrees: Students are often advised to complete their bachelor’s, master’s, and PhD degrees at different universities. The reason is that moving between universities exposes students to more faculty, diversifying the students’ influences, networks, and opportunities. While this is not possible for everyone, there is general wisdom in this advice, and you should consider looking at options beyond your familiar stomping grounds.

• Personal: This is the tricky one. Do you have personal reasons that place geographic restrictions on your choices? The toughest challenge is balancing your interests with those of a partner; you may also have other family obligations or reasons. There’s no simple answer here since only you can decide the sacrifices you are willing to make.

There will be tradeoffs among these six considerations for deciding which programs to apply to, and we cannot tell you which is most important. But we can say that your decision should not rest overwhelmingly on just one. We are going to say that again—don’t make your decision based solely on any one of these. It’s fine to have one be the key reason … as long as others are also supporting your decision.

Is doctoral study a good time to have kids?

There is never a “good time” to have kids. As it is sometimes said, if the continuation of the human race depended upon people rationally waiting for the right time to have children, humanity would have died out long ago. As many potential and actual PhD students are of prime childrearing age, two questions will often arise: “Is this the right time to have kids?” and “Is this the right time to do a PhD?” These questions are often of particular concern to female students. While men also struggle with this balancing act, there is considerable evidence that balancing parenthood and academic life at all stages is more challenging for women than for men, with women being more likely to pay a “baby penalty.” Challenging this is a structural problem that is beyond the capacity of this book, but it is important to at least understand the reality and how to approach it.

We have no instant answers, but we do suggest that you keep a few things in mind. First, it is hard to truly understand how exhausting babies and young children are until you are living with them full time. They are wonderful, delightful, cute as can be, and they will wake you up in the middle of the night repeatedly for five years or so (or at least it will feel that way). That being said, you will feel this exhaustion whether you are in a doctoral program, working, or a stay-at-home parent. Second, raising children can be more expensive than one anticipates, and managing child care (much less paying for it) can be more complicated than one anticipates. As doctoral programs are not the path to short-term riches, it is important to give careful thought to how potential financial and other stresses will impact your family life. Finally, many aspects of PhD life are more amenable than other lifestyles to young families, particularly the potential for (somewhat) flexible schedules and the ability to work remotely (such as from one’s kitchen while the baby naps—oh, please, let the baby nap …). The challenge lies in making this flexibility work in light of the demands on one’s time and energy.

If you are (or plan to be) balancing a PhD program and a young family, your need for strong organizational skills and a clear plan of action, as we recommend throughout this book, is particularly high.

What should I put in my application?

PhD applications typically involve lots of forms and grade transcripts, arranging for reference letters, and writing a plan of study. While the GRE (Graduate Record Examination) is almost universally required by American institutions as a condition of entry, its use is more mixed in Canada and other countries, and many programs do not require it at all. Instead, apart from your grades—which you cannot change—the two substantive areas to focus on are reference letters and the plan of study.

Students in large undergraduate programs often struggle to find good references from faculty who know them more than superficially, though by the time you are applying for a PhD, you will hopefully have some strong relationships with master’s professors. The exact importance of letters can vary by program, discipline, and the level of competition; sometimes letters serve mostly as a form of due diligence to ensure the committee is not missing anything, but at other times letters can be the clincher, particularly in highly competitive programs and scholarship decisions. While it is important to get letters that can speak authoritatively about your abilities, it is not the end of the world if you can’t find a magical dream mentor to write you the perfect letter. What you can do is ensure your referee has the necessary information to write the best possible reference—supply them with your transcript, résumé/CV, graded assignments from any courses you took from them, and information on why you are applying to a particular program. (We revisit how to get the reference letters you need in chapters 5 and 8).

The plan of study is more crucial, though again not necessarily for the reasons you might expect. While a plan of study is indeed an opportunity to demonstrate your academic depth and potential, it is also an important guide to a committee on whether you will be a good fit and have reasonable prospects for success in a program. Saying you want to study a topic related to Africa in a department that has no Africanists is a bad sign (not to mention an indication of lousy research on your part). This is particularly important for smaller programs that admit just a few students annually.

A difficult challenge is knowing how specific to be. Some plans of study are distressingly vague (“I love studying great thinkers and want to do a dissertation on one of Plato, Aristotle, Machiavelli, Kant, or Nietzsche—they’re all so great!”), suggesting that the applicant will indeed love grad school, but will never come up with a plan that allows them to leave it. But other plans are so specific that a committee wonders if there is any potential for growth (“My dissertation will focus on the use of commas in Anne of Green Gables”) and whether there’s any point in the applicant going to grad school at all. A Goldilocks approach is inevitably best—laying out some clear, broad ideas of what you want to look at, but leaving lots of areas to fill in and expand.

Contacting potential supervisors beforehand is generally a good idea; if you think you’d like to work with Professor A, reach out to them by email. They will typically be polite and non-committal, but the resulting correspondence is a chance for both parties to get a superficial but useful idea of each other. If Professor A finds your ideas interesting and thinks they might want to work with you (or doesn’t but refers you to Professor B, who does), this will likely boost your application’s chances; if not, better to learn that now rather than over the next five years. However, we advise against sending scattershot inquiries to half the department. Do some research and target your inquiries toward specific people, particularly the graduate program supervisor.

Box 2.1: Sample letters to prospective supervisors

Bad letter:

Hi. I am thinking of applying for your PhD program and think you might be a good supervisor. [For extra demerit points, write that line separately to several different people in the same department.] I am really interested in [three very different subfields]. I really liked your book [title partially wrong] and would like to work with you. Do you have any research grants and are you looking for research assistants? Can you call me to discuss this?

Joe

Good letter [adapted from a real example]:

Dear Dr. Green,

I am an ma student in [discipline] at the University of X considering applying to the PhD program at [Dr. Green’s university]. I am currently working on my thesis under the supervision of Dr. A, due to be completed next summer. My thesis is a study of [blah-blah-blah] entitled [“suitable scholarly title”].

Were I to be accepted to [Dr. Green’s university], I would like to continue work on [subfield] under your supervision. I believe that your expertise in [broader field] would provide me with an excellent framework within which to continue my studies of [subfield]. I have attached a tentative research proposal to give you an idea of what shape my dissertation might take.

I look forward to hearing from you.

Sincerely,

Joe McFadden

In the end, though, grades are typically the biggest single determinant in admissions decisions … and in the financial offers accompanying admissions decisions.

Should I apply for external funding on my own prior to entering a program?

Absolutely. The most common external funding source in Canada for PhDs is Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) doctoral fellowships; some provinces also have their own programs. Receiving money is obviously a good thing, but grants can be very competitive, deterring some students from investing the additional time needed to apply for them. Yet, as we explain in chapter 5, the ability to secure money is also a career-relevant skill on its own that you should start developing as soon as possible, making it worthwhile even if you are not successful this time. On top of this, having external funding makes you even more attractive to prospective programs: It shows that you set and achieve goals and gives you a stamp of approval from an external source.

How do I decide which program acceptance to take?

An offer of admission to a doctoral program is normally accompanied by offers of financial assistance. Practices vary here. The offer will generally be a mix of a teaching assistantship (TA) or other paid work and scholarship money. Individual faculty may come up with extra research assistantship (RA) funds as well. Some programs may also offer waivers that cover your graduate tuition—a potentially huge difference to watch for. Some aspects of funding may be one-time and others are guaranteed annually for a specified period (usually four to six years). Some programs may offer specific recruitment incentives, such as a subsidized campus visit to help swing your decision or moving expenses.

Sometimes, though, there is no money offered at all. It is rarely in your interest to pursue a PhD without funding, and practically never in your interest to go into substantial debt, especially right at the beginning of the program, for several reasons. Apart from the basic principle of needing to live and eat while in the program, the uncertainty of what will happen afterward—or even how long the program will take—makes it inadvisable to incur major short-term costs on the assumption of long-term financial gain. This is different from professional degrees in medicine, law, or business, which have moved almost entirely to a model of charging high tuition that drives most students into substantial debt, on the assumption that graduates will reap lucrative career earnings in the end. It’s also different than undergraduate programs, where borrowing to earn a university degree is (up to a point) a reasonable investment.

In contrast, a doctoral program is a journey into the unknown, and funding at least provides a partial lifeline through the void. A financial assistance package will rarely cover all your living costs no matter how minimally you live. But it’s a start, and a big one. It partly makes up for income you could be earning if you hadn’t made the decision to go to grad school. And funding—especially TA or RA work—is professionally validating. It says that someone values your work.

While some professional doctorates may not offer funding packages (under the medical/law school principle above), it is otherwise normal for PhD offers to include money. So what does it mean to receive an “unfunded offer”—that is, admission, but no money? We won’t mince words here: Typically, it means you were at the bottom of the admission pool—good enough to be let in, but not valuable enough to pursue aggressively. (This does not necessarily apply if you are an international applicant [i.e., not a Canadian citizen or permanent resident] because funding packages might only be available to Canadian applicants.) An unfunded offer might suggest they see you as a middling prospect and revenue source that will generate tuition and grant dollars for the institution with minimal investment on their part. It’s not a good sign. Even if you have the means to get by without funding and without incurring substantial debt (a continuing job, family money, earnings from a previous career, poker winnings, etc.), an unfunded offer suggests the program isn’t willing to bet a lot on your success. Having said that, it’s still an offer of admission and a chance to prove your worth. But be warned.

More common is to receive offers from a handful of programs, each with different levels of funding. This is much trickier, and if you simply accept the highest figure, you haven’t been reading this chapter closely enough. Instead, go back to the earlier points on choosing where to apply, and recall the central theme of not relying on any single factor. That’s important here as well.

Let’s say you get offers from Universities D and E, and University E’s offer is $5,000 above University D’s. This is a big enough difference to matter, yet not big enough that it alone should drive your decision. Whether you follow the money depends on what each has to offer. All the earlier points apply—prestige, bench strength, and so on—and possibly new ones such as cost of living and quality of life, since $5,000 makes a difference in those areas. If you have the possibility to visit the departments in question and meet people in person, this can be very helpful, but doing so can be challenging logistically and financially, particularly in a country as large as Canada unless the program provides funding to do so.

As with the applications, only you can truly decide here. Commonly, higher sums come from smaller and/or less prestigious programs that know they need to do more to attract you; bigger, more prestigious programs may offer less, not necessarily because they’re stingy but because they have so many more applicants that they don’t feel much need to woo you. But there’s some good news at this point: You may have room to negotiate. When it comes to the initial offer, the figure is usually firm—graduate programs, unlike used car dealers, do not make opening bids expecting you to counteroffer. But if you have two competing offers, the program has an incentive to negotiate and will usually do so, though not in large amounts since most of the funds have already gone out in the initial offers and they usually have to scrounge around to find anything more. But be open with them about who and what they’re competing against, and they may well come up with something. In the above example with the $5,000 difference in offers, University D might up its offer by $1,000 or—let’s get crazy—$1,500. In contrast, if you have two similar offers, you might squeeze a few extra dollars from one of them, but unless you are a real superstar with a faculty member pushing strongly for your admission, no program is going to get into an expensive bidding war for a prospective graduate student.

Whatever you do, don’t take on credit card debt for your program. If you are contemplating a PhD program you are presumably a smart person, and credit card debt is not a wise choice.

Our experience: Jonathan

I applied to four PhD programs and was accepted into two, both of which made similar financial offers. One was at the place where I was currently doing my ma, which was a very good university with a terrific graduate student community. But I chose the other program, at the University of Toronto. Here’s why:

• I decided it would be a good idea to go to a third university, increasing my exposure to new ideas and people.

• I liked the U of T’s reputation and bench strength, though at the time there was no single faculty member that I particularly wanted to work with.

• I wanted to return to the rich Toronto political and professional environment I had encountered while working at the Ontario legislature, which I felt offered the best variety of long-term career prospects.

What is the difference between a scholarship, teaching assistant (TA), and research assistant (RA) offer?

The funds that programs offer you will have different levels of strings and duties attached. Typically there will be a combination of scholarships and teaching assistantships, or possibly research assistantships as well. Straight scholarship money itself may come with no particular duties or obligations (other than to do well in your program), while teaching or research assistantships are tied to specific work duties.

Teaching assistantships

Teaching assistantships typically involve grading, leading tutorial or laboratory sessions, or some combination of these activities. You will typically be assigned to a specific class for a term, and you will need to ensure that you work your own schedule to accommodate the class schedule. It’s essential to recognize that a teaching assistantship is not just convenient money for you—it’s a job, and this fact escapes some students. If you ask to vacation to the family cottage at the same time when the final exam grading needs to be completed, chances are good that the course instructor will be highly displeased. When working as a TA, you need to clearly map your responsibilities into your schedule and then work your own coursework and research activities around these teaching responsibilities. The good news is that TAing allows you to develop your skills as a communicator and manager of your time. And developing a reputation as a good TA will enhance your prospects for other work such as research assistantships, opportunities to teach your own courses, and your overall professional standing. Crummy and indifferent TAs are also noticed and remembered, but not in a good way.

Research assistantships

Research assistant funding is typically offered to students by individual faculty members with research grants. Research grant funding frequently stresses graduate student training, so the entire idea behind an RA position is that you will be trained, through the process of doing research, how to do research. What types of tasks can you expect to handle? This will vary by the project, the discipline, the individual faculty member, and—over time—the level of skill and responsibility you demonstrate. In the early stages, the faculty member will likely start you off on broad, lower stakes tasks, such as collecting information for a literature review. Once you have demonstrated competence and trustworthiness, the types of tasks may become more challenging and enriching. You may even be invited to collaborate on research and publishing. However, the supply of research assistantships is not always predictable and requires a good fit between researcher and student. Some turn out to be life-changing opportunities, but others are more perfunctory and strictly transactional. And some are miserable fits that one or both parties eventually regret.

As mentioned, your funding offer will often include a mix of scholarship, TA, and RA funding. In assessing the total package, you should consider the work involved and how you will balance your various responsibilities. You may decide that a smaller offer of straight scholarship funding is more attractive to you than a larger offer that will require a considerable amount of time and attention. On the other hand, TA and RA work allows you to build career-relevant skills, which is an important goal of your doctoral program.

Is there a chance that additional funding opportunities will emerge during the course of my program?

Yes. As you spend time in the program, and as you demonstrate your capabilities, professionalism (see chapter 7), and winning personality, there is a decent chance that faculty members (including, but not necessarily, your supervisor) will approach you to take on additional TA or RA work, and when you are later in your program you may even be given an opportunity to co-teach or teach an undergraduate course.

If these opportunities emerge, you will need to make strategic choices in whether or not accepting these offers is truly in your long-term interests. More money is always nice, and avoiding debt is a key long-term consideration. Additional factors that must be weighed, however, include the risk that you will end up pouring quality time into other people’s agendas while rationalizing (sometimes falsely) that it advances your career. Teaching your own course is particularly risky: It may offer double the money of a teaching assistantship, but will be 200–300 per cent more work. In the end, be very careful about accepting anything that does not offer a clear benefit to your future employability. When you consider the costs of another year or two of tuition, living expenses, opportunity costs (i.e., the money you could have been earning if you graduated earlier), plus the increased risk of program incompletion as time drags on, the financial benefits of taking on too much become highly suspect. Consider whether the time devoted to such activities might be better allocated to other activities (such as those outlined in chapter 4) that are truly beneficial to your career.

For these reasons, combined with the fact that additional funding opportunities will not necessarily emerge, we feel it is critical that you make your initial decisions based on the assumption that the funding package you accept will be the entirety of your funding for the duration of your program. There is a time in one’s life for optimism, but gambling on additional funds emerging for you later in your program is not a great idea.

What do I do if I have already started my program and see things I could have done differently?

Chances are good that there are many great things about the decisions you have made so far. The reasons that motivated your choices undoubtedly had some merit, and it is important to recognize this. There is also the opportunity to use the information you now have to ensure that you make choices moving forward that propel you toward your goals. What are the strengths of your current program, and how can you most fully take advantage of these? Where are the gaps between where you are now and where you want to be leaving your program? The next two chapters will tell you how to take action to fill these gaps.

There is still time. There is always still time.

Our experience: Loleen

I did not have a thought-out approach to my graduate school choices; my decisions were influenced by finances and faculty (see “bench strength,” above), but were largely based on personal considerations. The program served me well, despite my somewhat impulsive decision making: I pursued classes in other departments, completed summer statistical training at another university, and did a Fulbright program; furthermore, and importantly, my supervisor and committee members provided me with individual mentorship that shaped my career. While I would engage in more strategic and careful decision making if I were making the decision today, I had a well-rounded experience that has served me well.

So, what should I do?

Part of the fun of Choose Your Own Adventure books is seeing how different information and circumstances structure choices and outcomes. There is abundant information available to you as you consider your graduate school options—first the question of whether or not you should really pursue the degree, then what schools to apply to, and finally what offer to accept—but it takes work to obtain this information. As the decisions you make will determine how you spend the next four to six years, it is a wise investment of time and energy.