Chapter 5 Establish Your Funding Track Record

In his 1990 pop classic “Freedom! ‘90,” the late, great George Michael sang, “Everybody’s got to sell.” Years later, Daniel Pink put forward a similar thesis (but without an accompanying music video featuring supermodels and a burning leather jacket, sadly) in his book To Sell is Human (2013). While the social sciences and humanities often consider the importance of framing and narrative, academia tends to discourage blatant allusions to sales and the idea of persuasion; there is often a prevailing sense that ideas and individuals advance purely on the basis of objective merit. This leaves those with a natural instinct for persuasive communication with a distinct advantage, and those clinging to the idea that “this idea speaks for itself” clinging just to an idea, with no actual funding for it.

Whether one is asking for funding, a job, or resources for their unit or organization, the ability to successfully make a persuasive case is a highly valuable career skill. Applying for grants and awards is a perfect opportunity for you to develop this ability and increase your comfort in acting as your own agent by making a case for yourself. Further, grants and awards are an external marker to the outside world that others value your research—value it so much, in fact, that they will devote money to it. And, of course, this is all in addition to the basic advantage of having financial support as you complete your program. So, given your need to develop the skill of creating persuasive cases to allocate limited resources for a particular cause, and given your need to, well, eat and pay rent, when you consider our overarching question—Given both my future goals and the information currently available to me, what is my best decision right now?—applying for grants and awards is easily a good choice. There is so much to gain that we are going to jump right in.

What is the difference between a grant, a fellowship, a scholarship, and an award?

These terms may be used interchangeably. A grant is typically funding provided to an individual (or team or institution) that is not repaid (unlike a student loan, a line of credit, or worse, credit card debt). Fellowships and scholarships are both types of grants. There are some fellowships out there that do not have funding, offering prestige and profile alone, but typically this is not the case. Award is an even more slippery term; typically, awards are things given after research or an activity is completed, such as awards or medals for the best dissertation, journal article, or book in a given year, but sometimes funds are given during the research process that are called awards. Some awards carry cash value, while others involve prestige and a nice certificate for your wall but no actual money. (Another entity to quickly mention is bursaries, which are awarded partly or entirely on financial need criteria, but they’re outside our focus here.) As the language used is imprecise, we use the term “grant” for any scholarship, fellowship, or award that provides research funding at the start or during a research program, and the term “award” for any honour that is given (with or without money attached) to a completed activity.

What is a funding track record, and why do I want one?

Throughout this book, we have encouraged you to take steps to position yourself for a number of career opportunities, including but not limited to academia; we have repeatedly encouraged you to set your goal as a successful, rewarding career that uses your talents and the skills you developed throughout your education. Creating a funding track record—that is, a record of external grants and awards—will help you achieve this goal. Grants and awards provide future potential employers with a clear indication that your research is seen by others as meritorious and valuable. For careers in general, grant writing and generally pitching for opportunities and money is an important skill. And if you have any interest whatsoever in an academic career, you should be applying for grants and awards—note that we used the plural forms—because hiring committees are looking for evidence of research potential, and external funding provides one indisputable form of such evidence. Overall, a funding track record is increasingly a necessity for competitive academic job applications and may be a distinct advantage for applications in other sectors as well.

There are more immediate benefits to you as well. Constructing competitive applications requires you to cultivate your ability to explain your research in a compelling manner. The capacity to describe your research in a manner that excites others, answering the “so what?” question, speaks to your communication skills. Moreover, it is often in describing your research to different audiences that you start to notice areas for improvement in your work (holes in your argument, gaps in your literature base, limitations to your methodology) that you can address as your research evolves.

As many applications are not successful, applying for grants and awards provides you an opportunity to build comfort with risk taking and rejection. Many PhD students are accustomed to success; PhD students become PhD students because they were successful undergraduates and then successful master’s students. Experiencing failure is an uncommon experience; you might have received a lower grade on a paper than you expected, but actual failure may have been rare. The problem with this continued success bubble is twofold: You might unconsciously stay within this comfort zone and avoid things that risk failure (and thus avoid the associated rewards with such things), and once you wade into publishing (see chapter 6) and into the job market (see chapters 8 and 9) you are going to need to get used to rejection. Applying for grants and awards helps you develop a thicker skin early and learn to be reflective about why you did not succeed so that you can make the necessary adjustments for future success.

And finally, the obvious advantage of grants and awards is money to support you and your research. If you already have external grants, there is a chance that you may be allowed to hold multiple grants at once. Even if you are not permitted to do so (and look into that carefully before assuming you cannot), you can use the offer of the grant on your résumé or CV as evidence of your ability to secure funding. It is better to list that you had to decline funding due to all of your other fabulous funding than to not apply.

Bottom line: Apply for grants and awards, even if you have other funding, even if you have sufficient employment income, even if you have a trust fund, and even if your partner or a family member claims to be “happy” being your sole supporter for a few years while you pursue your intellectual dreams. Keep applying throughout your program. Individuals are always striving for ways to distinguish themselves in competitive employment markets, and a funding track record is a great way to do so.

Our experience: Loleen

I applied for a number of grants and awards during my doctoral program, sometimes successfully, sometimes not. When I began my career, I quickly found that my past work in applying for funding was relevant to (and valued by) the not-for-profit I worked for. I soon was asked to assist with, and then eventually take responsibility for, writing grant applications to governments, philanthropic foundations, corporations, and other entities. Every potential funder had different information needs and required a specific “tone”; when looking to put together different funding sources for the same project, I was required to adapt to meet the needs of the audience, playing up certain aspects, providing varying levels of detail. My experience in applying for grants during my doctoral program provided me with the starting foundation that I built upon during my 10 years in the not-for-profit sector. I learned as much from my failures as I did from my successes, and it benefited my career.

When should I start building my funding track record?

In an ideal world, students start to build their funding track record as soon as possible. One can imagine the mythical strategic student who starts applying for grants and awards in the first year of her undergraduate program and then continues amassing honours small and large throughout her undergraduate career, pauses for a year as a Rhodes Scholar (of course), moves on to apply for a prestigious master’s scholarship, and then for an even more prestigious doctoral scholarship, turning down Opportunity A in favour of even more lucrative Opportunity B. If this was you, congratulations, and we encourage you to be humble about such efforts to avoid alienating others. For everyone else, the time to start learning how the research grant world works and to start applying for grants and awards is now. It is not too late. It is possible that some (perhaps many) ships have already sailed, but it is just as likely that opportunities continue to exist for you.

Once you have identified an opportunity, aim to start working on your application at least two months in advance of the deadline. This lead time allows you to develop multiple drafts, solicit feedback from others, and generally polish your application for a greater chance of success. It also allows your nominator or referees (assuming you require such letters) time to develop strong, targeted statements of support that are informed by your application materials, rather than a generic “I taught Sally two classes and she wrote a good paper in each” letter that will not help your case. (See below for how to get the nomination letter you need, and chapter 8 for how to get the reference letter you need.)

At all stages, to be sure, pay careful attention to eligibility requirements; for example, some grants only allow you to apply a specified number of times, so you need to be strategic in when you choose to apply. But making the decision that you will make yourself aware of the opportunities out there, and then devising a plan to take advantage of them, is a good place to start.

How do I learn about grant and award opportunities?

Grant and award opportunities fall into two broad categories. The first are awarded to you with little to no effort on your part. (Sweet!) For example, your graduate program may automatically award scholarships based solely on grades; you may be required to submit a transcript, or they might just manage it on their own. Similarly, your department might submit all or a subset of completed dissertations to your disciplinary association for consideration for a best dissertation award. For such opportunities, there is not much you can or should do to advocate for yourself, other than sitting down with your supervisor and your graduate chair to find out what the opportunities are and to politely indicate you would appreciate being actively considered for anything that might be available. Departments can vary in the clarity and format of how such awards are allocated; in some cases, it’s just up to the graduate chair to pick deserving candidates every year, and it is not unheard of for awards to not be given out because they are simply overlooked. Overall, there can be value in general networking and making sure to leave no stone unturned, but at the same time it’s not always clear how much agency PhD students have for these types of awards.

Our experience: Jonathan

One day as a newish assistant professor, I opened up an email and discovered my book, based on my dissertation, had won an award as “book of the year” from an international research group that I really respected. Not only had I not applied for the award, I wasn’t even particularly aware of it, and I am still not exactly sure how my book even got submitted. But it was a really meaningful honour that I am proud of, and it continues to look good on my cv. I was very fortunate that someone else was looking out for me, because I wasn’t paying attention.

Our experience: Loleen

The unexpected emails I have received include spam and a mildly threatening hate email in response to an opinion editorial I wrote. Jonathan’s experience is not typical.

The second category of opportunities are those for which you have greater agency, in that you are able to apply for them directly or through your program, providing a written program of research, CV, or other supporting materials that you can refine and tailor for the opportunity. You can imagine awards and grants as being on a ladder: The bottom rung contains those solely based on grades and past performance, and as you move up the ladder your agency increases because the importance of pitching yourself and your specific research grows. Your goal should be to aim to move up the ladder, building your skills.

To identify opportunities in this second category, you will want to undertake your own research, considering travel scholarships and awards (such as the Fulbright Program), government awards and grants, and private awards and grants. Because universities vary greatly in the amount of information they provide online, visit the graduate faculty webpages of numerous universities; this list should include your own university (or, if you are not already in a program, any university to which you plan to apply), other doctoral universities in the same province (as many funding opportunities are province specific), and then some from large, research-intensive universities in Canada. (If you are in a program outside of Canada, adapt these categories as needed.) Across the graduate faculty webpages you are sure to notice considerable overlap, but you may also find opportunities present on some sites that are not on others. Beyond this, conduct basic searches for opportunities specific to your discipline and topic, speak directly with your supervisor and your departmental graduate chair, and attend any research funding workshop offered at your university or by your disciplinary association.

Why are SSHRC grants such a big deal in Canada?

In Canada, arguably the most important grants are from the Tri-Agencies, which are the three federal academic funding agencies: SSHRC (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council), CIHR (Canadian Institutes of Health Research), and NSERC (Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada). Tri-Agency funding is important to universities, not just individual faculty; while the formulas and arrangements change over time, a significant portion of university funding is based on how well the university’s researchers do at securing Tri-Agency funding. Universities typically receive an overhead amount as a percentage of each grant, allocations of other national awards are based on Tri-Agency success, and provincial funding formulas to universities may consider Tri-Agency funds among the metrics for fund allocations. The stakes, in short, are high, and many universities place clear expectations on faculties, departments, and faculty members to secure such funds because the initial grant is a foundation for so much more.

For social science and humanities students and scholars, SSHRC is by far the granting agency of interest, and for this reason we will focus our comments on this agency. Academic job candidates who have a SSHRC funding history, be it a master’s scholarship, a doctoral scholarship, a postdoctoral fellowship or—ideally—all three, can be particularly competitive in academic job searches. Due to the institutional incentives for Tri-Agency success that ripple down to the departmental level, departments are keenly interested in a candidate’s future prospects to obtain Tri-Agency funding when hiring for academic positions. A candidate’s demonstrated ability in securing such funding as a graduate student or postdoctoral fellow is thus seen favourably. Other awards are also viewed favourably, but typically they do not have the prestige or the long-term Tri-Agency value implications of SSHRC awards.

How do I make my grant application competitive?

With grant applications, you are competing for limited resources. The adjudication committee has a finite number of grants to give out, and you must persuade them that your proposal is not just meritorious and meets the grant criteria, but also worthy of being selected above other meritorious applications that also meet the grant criteria. To be persuasive, you must appreciate and respond to the perspectives of others, see the world through their eyes, and identify how your work meets their needs. Essentially, you need to frame and position your work in the manner that suits them, rather than what makes sense to you. Achieving all of this requires three things: (1) a deep understanding of the grant criteria, (2) a compelling case that your work is worthy of being selected over other worthy projects, and (3) time.

Grant criteria

The grant information page will provide you with details about what types of projects and scholars are eligible, the adjudication process, and technical criteria. All of these must be taken very seriously. If you are ineligible, you should find something else to apply to, obviously. But look carefully at the purpose of the grant and the evaluation criteria, as these give you important strategic clues about how to position your work. Be bold and explicit in stating how you meet these criteria. For example, if the criteria are originality, significance, and feasibility, address these points directly:

• My project is original because x.

• The research question is significant because a, b, and also c.

• My research plan is feasible because [your training/planned training], [your access to data], and [your realistic timelines].

The adage “show, don’t tell” is intended for fiction writing, and your grant proposal is not—or at least should not be—fiction. Tell explicitly, and then provide evidence to support your claims (tell, then show). As you work to explicitly address the criteria, you will at times struggle to make a strong case. This realization is good, as you can then do additional research or make additional refinements to your project to fix the deficiencies. Your research program overall and the grant application will both benefit. Finally, address the technical criteria. If the application requires you to use 12 point Times New Roman font, for goodness sake pay attention to this and make sure you comply! Failing to meet all of the technical criteria may get your application disqualified (all of that work lost because of your dedication to APA citation style!) or at the very least will make you look sloppy in your work.

Compelling case

Many grants—particularly those higher up the ladder rungs—require you to include a program of research or study plan. To succeed in these competitions, you need a clear narrative: a specified research question, a link to existing scholarship, and a plan of study (feasible methods and a timeline) that demonstrates how you will answer the question to build upon and advance that existing scholarship. Once you have outlined this information into a functional draft, you then need to revise it to make it compelling in the eyes of the adjudication committee. Your goal is to excite reviewers with the potential impact of your research, and the high likelihood that you will achieve this impact. As you revise your first and then your second draft, try to put yourself into a reviewer’s mindset. Imagine a reviewer who is not a specialist in your subfield or even your discipline. Aim to impress them with your clarity, not your jargon and ability to use fancy words or drop big names. And as you revise, always look for ways to increase the energy in your application: Consider using the first person, kill all forms of passive voice, and find compelling verbs.

Table 5.1 Worksheet: Clarifying your work’s significance

Question |

Considerations |

Your Answer |

|---|---|---|

In one sentence, what is your research question or objective? |

This sentence must make sense to all audiences. If you cannot successfully explain it to the grocery cashier, your dentist, and your hair stylist (assuming they are willing to listen to it), keep revising. |

|

Why does this work matter? How will this work help society? How will it advance theory? |

Just because it is important and obvious to you does not mean it is to other people. Why should tax dollars be used to fund this as opposed to (idealistic vision) medicine for sick children or (pessimistic view) large gala events to celebrate government achievements? |

|

How is your work original? |

Demonstrate not only that you know the research area but also that your approach is original in some way; be explicit that the question is not answered by previous research and that you aren’t just proposing to repeat previous research in a different population or time frame. If your research is just “adding to the pile,” your grant application may be moved to the bottom of the pile. |

|

What evidence is there that you will be able to complete this work? |

Being overly ambitious can be risky; while you want to generate excitement, you also need to instill confidence that you will be able to get the work done. Provide a realistic timeline and a compelling case that you have the necessary training and data access to see the project through to success. Feedback from experienced researchers is invaluable here. |

Time

The benefits of starting early on grant applications cannot be overstated. Starting early allows your ideas to percolate and evolve, and allows you to practise your ideas on different audiences for feedback, improving your ideas iteratively. As you read the second point above, you may have noticed that we mentioned writing multiple drafts. We recommend that you aim to never submit a first draft; ideally, you will have an initial draft, then receive feedback from a number of sources, and revise your application in response to this feedback. In working out your timelines for the application, double check the submission deadlines with your unit and university graduate faculty, as individual universities may have internal deadlines prior to the funding agency deadlines.

How can I be competitive for SSHRC doctoral funding?

Your personal ability to access highly competitive SSHRC funds varies at different stages in your academic life. (We should further note that there are different levels of SSHRC doctoral and postdoctoral funds, varying in competitiveness, prestige, and dollar value, but the general processes are largely the same.) One immediate point is that, at the time of writing this book, most SSHRC doctoral opportunities can be won either at the start or in the middle of your program. Indeed, your program may require you to keep applying every year that you are eligible as a condition of your existing funding. This is a huge gift to late(ish) bloomers who may not have outstanding records or really clear research plans upon entry, but really shine in the first year or two of their programs. It also reduces the arbitrary timing of funding if your PhD entry cohort includes Genius A and Mastermind B, both of whom win scholarships that you would otherwise be a contender for.

Check the SSHRC procedures carefully, which change over time but have mostly gone in the direction of devolution except for the most prestigious scholarships and fellowships. Applications that were once all sent to Ottawa for national adjudication are increasingly handled solely within universities, faculties, and even departments themselves, with most universities given a quota of scholarships or a certain number they can nominate. SSHRC applications are infamous for their tight word requirements while being reviewed by broad disciplinary and multidisciplinary committees, putting a special premium on being able to articulate both depth and breadth at the same time. Strong applications use every word with care. Ensure your referees have your exact plan of study, so that their references can amplify and extend your own points. And, as we noted in chapter 2, application deadlines are typically well before the regular admissions deadlines, meaning you must be an early bird to have any chance of enjoying what is considerably more tasty than a worm.

Do not be discouraged if your SSHRC application does not succeed; rather, inquire how you might strengthen it for subsequent years (and for other types of competitions). Grades are typically the single most important factor in decisions, but by no means the only one. Review with your graduate chair or others involved in the various levels of adjudication how you might do better next time. They may be able to offer some useful insights or show you examples of successful applications that will inform your thinking.

Typical grant and award criteria

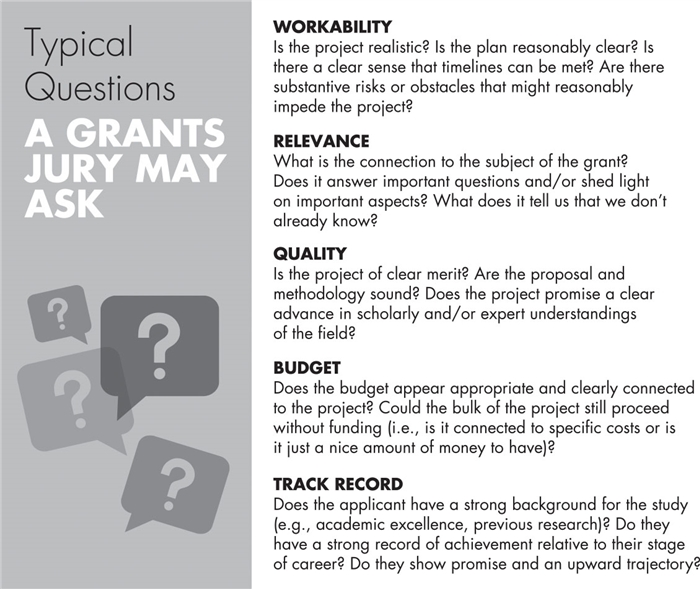

Calls for grant and award applications typically include at least some mention of adjudication criteria; though it may be brief or buried in the text, a careful reading may give you some great guidance on how your application will be assessed, especially for individual specialized grants and awards. Figure 5.1 shows one set of examples.

Figure 5.1: Typical questions a grants jury may ask

How do I ask someone else to nominate me for an award?

Here is the perfect world: You open your email to find a surprise notification; you have been selected for the distinguished Great PhD award, or as a top 30 under 30 (or 40 under 40, since 40 is the new 30) award, or some other honour. You had no idea you were even being considered! Was it your supervisor who nominated you? Or your department as a whole? You are so touched and grateful; all this time you were quietly toiling away, they did notice!

We do hope this happens for you. At the same time, we want you to take whatever reasonable steps you can to strengthen your CV and résumé. And if this involves awkwardly asking someone to nominate you for an award, so be it. The fact that your supervisor or anyone else has not nominated you for any given award does not mean they don’t think you are worthy of the award; it is equally possible they are unaware of it or just busy with other things.

Here is how to proceed:

1. Identify all awards for which you might be eligible. Read the criteria numerous times to make sure you are in fact truly eligible, both in personal (level of study, citizenship, etc.) and project terms, keeping in mind that while the former are usually fairly fixed, the latter may be more flexible. Pay particular attention to disciplinary language and terminology to ensure you actually understand the broad parameters of the award and are on the same wavelength as the funders. At the same time, don’t rule yourself out too quickly, as the parameters may wax and wane over time, especially depending on who else applies that year. If you think you may reasonably qualify, and the work is not too onerous, it is worth a try.

2. Write up in bullet form a list of the award criteria and all of the ways you meet the criteria. Use clear evidence and elegantly worded sentences. This document will serve three purposes: (1) it will clarify in your own mind that you are both eligible and a worthy nominee; (2) it will create a case to your potential nominator that you are a worthy nominee; and (3) your potential nominator can use this document as the starting point for their nomination on your behalf.

3. Set up an in-person appointment with your potential nominator. Come to this meeting prepared with print documentation that provides full information about the award (including deadlines, addresses, forms, etc.), your case for your nomination, and any other documentation that might be needed for the nomination (such as your CV or a copy of your work). Impress your potential nominator with your professionalism, organization, and background work, and make it easy for them to complete the nomination for you. Do not worry about overwhelming them with information (within reason); rather, worry that they will complete the nomination without a key document or piece of information that you didn’t tell them about.

4. When requesting the nomination, state clearly to the potential nominator that you are seeking the nomination because you feel the award would be beneficial to your long-term career prospects, and ask if they would be able to provide a strong nomination on your behalf.

5a. If the person agrees to provide the nomination, ask what additional steps you could take to reduce the associated workload for them, and offer to follow up a week before the nomination is due to see if there is any assistance you might provide at that time. After the nomination is submitted, provide the nominator with a gesture of thanks, ideally a handwritten note or card rather than just an email or passing comment. If you receive the award, drop by to give them a second (yes, second) thank you card. It is hard to be too appreciative.

5b. If the person declines to provide the nomination, thank them graciously for considering the request. Reflect thoughtfully on why they might have declined, and consider if there is someone else you could ask to provide the nomination.

6. Regardless of the outcome of your request, and regardless of whether or not you receive the award, be proud of yourself for being proactive in trying to find ways to build your CV and résumé and for taking a risk.

Our experience: Jonathan

For several years, I was responsible for a student essay contest for the best paper about “Parliament.” It was meant in a political science definition of the institution itself and its procedures and reform. Yet every year we received a wide range of papers on topics that went well beyond the above definition. Some were clearly ineligible because they were about political issues that, while they may have been discussed in Parliament, were not actually about Parliament as an institution. Such submissions were a waste of everyone’s time, submitter and reviewers alike. But some papers were more on the edge, not primarily focused on Parliament itself but discussing other aspects of the political system (such as political parties) with clear references to the relevance for parliamentary institutions. They sometimes won depending on the quality and quantity of the overall pool that year. Ensure you are reasonably on target before you start applying, but sometimes you don’t need to be exactly in the centre of the target.

How can I learn grantsmanship from a faculty grant application?

Usually the best way to learn is by doing, or at least watching others do it. This certainly applies to research grants, by which we mean watching faculty as they compete for grants themselves. Ideally this will be a valuable way to learn how to do it yourself, but the opportunities will vary considerably.

We mentioned in chapter 3 that there is no Supervisor School, so most PhD supervisors replicate their own supervision experience as the only model they really know. Similarly, faculty tend to replicate their own past experiences with grants when it comes to involving graduate students in the process of application and competition. Most grant applications are unsuccessful, so for obvious reasons most faculty are inclined to not tell grad students (or anyone else who doesn’t need to know) about what they are up to unless it succeeds. But even when they do successfully obtain the grant, it doesn’t occur to most faculty to let grad students know how it was done, and it is even less likely to occur to graduate students to ask. We encourage you to ask faculty (nicely) about the process of their successful projects, whether they could share their winning applications with you, and how they planned and targeted the application—all while explaining that you are trying to learn as much as possible about the art of asking for money as part of your long-term career development prospects.

In more fortunate situations, you may be lined up as a potential research assistant or team member on an application, and while your input may not really be solicited, you have multiple chances to watch and learn as the application takes shape. Take advantage of those chances (and, using your judgment, look for ways to contribute). Ask why certain things are done (or not done) and what the team thinks the strong and weak spots are in each draft. And whether the application is successful or not, ask to discuss possible reasons for the outcome.

What do I do if I am at the end of my program and didn’t do any of this?

As we said earlier, there are numerous reasons to establish a funding track record, and the financial gains are not the most important among those reasons. As you approach the end of your program, your goal is to create evidence that demonstrates you understand the grant game—both the art of grantsmanship and pitching for money and the more general picture of how the grant world works in your discipline or area of interest.

Here are some steps you can take:

• Research what is out there that you can apply for as an individual student or scholar. Use this research time to educate yourself on the research grant world; be sure to have a solid understanding of SSHRC’s various programs and criteria, but also learn about other government, private, and not-for-profit/foundation funding options.

• Attend any research grant seminars that your university offers (how to write a grant proposal, how to create a Canadian Common CV, etc.)

• Let your supervisor and committee members know you are looking for experience with grant development, and ask if there are faculty members who are working on grant proposals who you might be able to assist.

• Organize a panel session on grant funding for new graduate students, inviting faculty and graduate students who have successful grants to serve as panelists.

• Conduct online searches on how to write successful grant proposals, even if you are not applying to anything in the near future.

• Look for ways you can develop evidence of your ability to write grant proposals and present compelling cases for funding through your extracurricular activities. It may be that your tennis club is applying for a community grant, or that you can take the initiative to find and pursue funding opportunities for your musical theatre group.

Above all else, be sure to maintain your own sense of personal agency; take the initiative to seek out opportunities or, if possible, to create opportunities for yourself.

How do I get comfortable with all of this?

Selling an idea—that is, getting people to buy into the need to support a project—is a skill set. Yet while this is a necessary skill for all of us, many academics are uncomfortable with the very notion of sales. They may associate sales with shady behaviour and with slick advertising campaigns. To all of this we say: Get over it. As your own agent, you must take steps to act in your own interest, and this requires understanding its importance and taking steps to develop this skill. It is a tool that will prove extremely valuable in your life ahead.

And now, assuming that we have successfully sold you on this idea, we will move on.