Chapter 6 Build a Strategic Publishing Portfolio

In academia, the importance of “publishing” (inevitably defined as traditional scholarly journal articles and books) is often expressed in terms of volume and measurement: “I got five publications out of my dissertation”; “the applicant has a book and two articles”; “this is a mid-ranked press”; “the article has a high citation count.” There is constant pressure, particularly for junior scholars, to score higher and higher on these measures if they wish to succeed in academic careers. Over time, publishing expectations have steadily risen, so everyone tries to publish more and to score higher on these measures to get ahead of those expectations—and each other. The result is a publication arms race. And no one really wins an arms race.

In this chapter, we suggest a different approach that defines publishing more widely and as part of a broader portfolio of your skills and competencies, rather than just having more than the next person. Project management and writing are fundamental parts of the PhD experience, especially in the social sciences and humanities. Luckily for you, each is also a key career competency: The world needs people who can take a project from idea to implementation to conclusion, and good writers who can communicate complex ideas and research into intelligible form. Publishing is a key mechanism to both develop and demonstrate these skills. The process of publishing is an education in itself that will benefit your career, and the product of publishing—that is, published work—demonstrates your ability to see projects through to completion, work with others (coauthors and editors), adapt to feedback, and communicate ideas effectively to external audiences who, unlike your dissertation committee, are not obligated to pay any attention to them. It is the evidence that demonstrates your ability. For this reason, you should plan to deliberately craft a strategy to develop a publishing portfolio that will support your claims about your project management and writing abilities, rather than just an arms race that you must win.

Do I really need to publish during my PhD?

Absolutely. You gain important skills in publishing that will make you more hireable both outside and inside academia. There are, of course, different types of publishing; we are limiting our definition to writing that has been reviewed and approved for public dissemination by someone else playing an independent editorial role. This can be in print or electronic, through a traditional commercial or scholarly publisher or an online editor, and really by anyone other than you or someone you are paying to “publish” the work. Work that has been reviewed for editorial quality and that has passed a firm test—publish it or not?—carries an external validation that personal online posts or your aunt’s self-published memoir does not. As an aspiring career professional, your publishing time and energy should be focused on work that has been validated by others.

In order to simultaneously position yourself strongly for numerous career opportunities (discussed further in chapter 8), think about developing a publishing portfolio that crosses formats and speaks to different audiences while drawing upon the same project and knowledge base. Peer-reviewed scholarly publications are the coin of the realm in academia and can (sometimes) have value elsewhere. For academic jobs, it is rare to get hired without existing peer-reviewed publications, leading to the arms race discussed above. But whether or not you aspire to an academic job, your portfolio should also incorporate other forms of written communication—such as short media opinion pieces (“op-eds”), articles, essays, and reports—as such publishing can be valuable outside of academia and are increasingly valued within academia as well.

A tougher question is how much and where you should publish. Again, we return to our guiding question: Given both my future goals and the information currently available to me, what is my best decision right now? Your time and energy are limited, and you want to make strategic publishing choices that create the portfolio you need. More is not always better, and quality, visibility, and impact all count. “Scholarly” publications take the most effort and have varying cachet, but there is also a risk in generating lots of easier but minor outputs that do not add up to much, suggesting you can dash something off quickly but questioning your bigger substance.

So yes, absolutely publish. But make careful choices, and make them count.

What should I publish on?

While the academic publishing arms race is ultimately all about how much you publish, our approach urges you to think as well about what you want to say and to whom. Where do you want your ideas to resonate? What impact do you want your work to have? In the long run, this is what will give you satisfaction and, particularly for non-academic employers, is typically more important.

As a PhD candidate, you have a dissertation that will hopefully be publishable in part or whole. But perhaps more importantly, you have a dissertation subject and expertise and knowledge in it. You may also have expertise and knowledge in other areas, say from your master’s work, or other things you are doing while working your program, though as we say below, this is the time to focus narrowly for impact rather than going off in multiple directions. This should be the start of your publication journey—having something to say and the competency to say it, rather than seeing everything only as chunks of material that will increase your volume count. (This is sometimes known as the “salami-slicing” approach of cutting research results into slimmer individual portions that can each yield a separate publication.)

You don’t have to say everything, of course. We say again that publishing should be strategic—writing things that add value to and impact your career. Some publishing can actually have diminishing returns, if you say the same thing over and over, select poor venues, or take on projects that eat up time but don’t really challenge you. Not only does this detract from other important tasks like completing your dissertation, attending a networking event, or spending time with loved ones, but too much low-level or repetitive stuff can suggest this is the limit of your ability and aspirations. Be alert to diminishing returns. As we will soon explain, it is important to keep focused on a single topic, so don’t keep chasing new directions. To build your reputation in a particular area, you may need creativity and novelty to ensure you are building value while publishing on a tightly focused topic. And to demonstrate your ability to write for different audiences, it is also important to try to diversify your writing outlets.

Are book reviews worth the time?

Scholarly journals in book-oriented disciplines are always looking for people to write reviews of recent books. While of service to the profession and gratifying to authors (“Someone read my book!”), this can be time consuming and of limited reward to the reviewer. Many PhD students see it as a first step on the publishing ladder, but it really isn’t. It is hard to write a truly good review, and readers will not remember who wrote it anyway—but the author will if you say anything they find overly critical. There’s not a lot of upside, but there are definitely a few downsides.

Should I publish from my dissertation before I defend it?

There are two kinda-sorta-good reasons to not publish from your dissertation too early. The first is that it takes time away from the goal of completing the dissertation itself. But as you know by now, we don’t advocate a single-minded focus on completing the dissertation at all costs. Publishing can even speed things up by helping you focus from a new angle. The second is that dissertations and the research behind them can take time to take shape, and waiting might allow you to produce much stronger publications in the long run—especially if you are in a book-oriented discipline that normally expects dissertations to be published as monographs. But waiting two to three years after your defence to hold your published dissertation in your hands in book form might not be helpful for your career goals. And if you head in a non-academic career direction, chances are good you won’t publish your whole dissertation anyway, and you will have missed the opportunity to publish your work. Short-term gain and immediate gratification are good here, because your goal is to build your profile, advance your project management and writing skills, and get jobs and opportunities, and your publishing should serve that end.

Of course, some dissertations don’t really break up into publishable chunks, so you might have to wait for the book. But most have at least one chapter, case study, or other piece of original research or reflection that can be turned into a peer-reviewed journal article. (Note that we specifically stated journal article. You want a proper refereed journal article if at all possible, because that appeals to potential employers and future hiring committees more than a chapter in an edited book. We will come back to this.) Consider the options available to you, and reflect on what best aids your career goals.

Should I publish on topics unrelated to my dissertation topic?

The challenge in working with ideas is that new topics are always so pretty, so tempting. Later in one’s career, it can be delightful to explore new ideas, tackle them, and be open to new things. This is not the case, however, when one is in graduate school.

Ideally, all of your work, from your course papers to your dissertation to any additional papers that you write, will focus on a single topic. In practice, you might find you need to explore a few (ideally related) ideas before settling on one; you want to be sure that the topic is feasible and that you can access the necessary data and make a unique theoretical contribution before you commit all of your publishing eggs to one basket. But after you are sure you have a viable topic, it is a good idea to keep a narrow and disciplined focus on it.

Focusing on a single topic, as opposed to a number of somewhat linked or (worse still) different topics, works best for a number of reasons. First, with every new topic that you examine, there is a new literature, or two, or (for those venturing into the sometimes frightening waters of interdisciplinarity) three, four, five … Mastering those literatures starts as thrilling and ends as being a lot of time and work. Simply put, it is more efficient for you to find a niche and develop it. Second, with every item you write that focuses on the same theme, you build your external profile in the area. Two or three pieces on the same topic can add more credibility than five pieces on different topics. Third, every time you focus and expand on the same theme, you build your own internal competence on the topic. Much has been written about “imposter syndrome,” the pervasive sense that everyone else out there is highly competent whereas you are just faking it. It is not a good feeling to believe that you are out of your depths. It does not feel good to believe that you only know the surface literature. Avoid it.

Where should I publish?

Regardless of your career goals, you should pursue scholarly publishing in some form during your PhD, and we will devote most of our discussion in this chapter to that. But in addition, we urge you to build your publishing portfolio by adding selected non-scholarly publishing. There are numerous opportunities to write for key non-academic audiences, such as industry publications, practitioner journals, and so forth. You should seek these out. Writing for these outlets allows you to learn how to write for different audiences (an important skill), and then provides you with evidence for potential employers and granting agencies that you can, in fact, write for a range of audiences. The publications allow you to increase your profile outside academia, which may help you to build networks (discussed further in chapter 7), while inside academia they are increasingly valued as part of knowledge mobilization. And such publications, often more so than academic publications, can have influence on ongoing debates and even practice. Such influence is both professionally and personally rewarding.

When deciding where to publish, variables to consider include the following:

1. The purpose of the writing: Is it advocacy? Reports and analyses? General interest or entertainment?

2. The audience: Is it the mythical “general public”? Enthusiasts or professionals interested in a narrow field? Decision makers?

3. The style: Big words? Data driven? Anecdotal? Simple and accessible?

4. Who initiated the writing: Are you responding to an open call for submissions? Were you approached to do it? Were you specifically commissioned to write something?

Any combination of these could be valid … or not. Beware the thirst of many outlets for content—any content, it seems, as long as they don’t have to pay for it. Sometimes, though, a publication may not have many readers or impact, but is still a mark of quality and a career-advancing move because you were asked to do it (many government reports fall into this category). We caution against publishing primarily for the sake of advocacy except on topics squarely in your area of research expertise; when you do publish advocacy pieces, be sure to make it about analysis more than opinion. The bar is often low here, and some outlets are always looking for quick opinions on controversial subjects, but resist the temptation to publish your opinions on matters in which you may be an informed and engaged citizen, but not a research authority or expert. We are not against saving the world, but we urge you to focus your time and energy strategically.

A publication can range from a few hundred words to tens of thousands (or more, in which case it’s called a book). This usually correlates to time commitment, though much depends on how much work you need to do before you sit down to write. It also correlates somewhat to impact and influence, but with more variance. A 700-word op-ed at just the right time on the right subject can advance your standing (and demonstrate your responsiveness and nimbleness) much more than 5,000 earnest but only modestly relevant words somewhere else. However, short writing usually only has a short burst of impact. Ideally you should look for both sprints and marathons.

You may well think at this point that this is all great, but this world of op-eds, public essays, and reports just doesn’t apply in your field. Yet we believe strongly that in almost any discipline or field in the social sciences and humanities, someone is looking for your ideas and research in written form (though they may not have money to pay for it). Admittedly, few government departments or corporate boards sit around thinking, “we need to commission an analysis of references to polar bears in nineteenth-century Germanic literature,” but organizations devoted to polar bears, the Arctic, or German literature might be interested in the aspect relevant to them. Sometimes the demand is certainly more obvious, but we urge you to take our above assertion as a given and think creatively about who that someone is. The first and best way is to consider the things that you read yourself. Can you see yourself fitting somewhere in there? Expand further to the wide universe of low-profile specialized publications, such as professional and industry journals, that have small but highly dedicated readers looking for engaging and substantive content. It doesn’t need to be a perfect fit and is unlikely to cover all your areas, but we believe you will see places where you could publish. You can then consider whether it is in your strategic benefit to do so.

In all cases, when pursuing these publications aim to keep the topic within your area of expertise, as discussed above, and to maintain a professional tone, supporting your positions with evidence. Further, while these non-academic publications are a great addition to your writing portfolio, they should not be the entirety or even majority of your writing portfolio; be sure to pursue scholarly publications as well.

Should I pursue scholarly publications if I have no interest in an academic job?

Yes. While non-academic employers may indeed be indifferent to your piece in the Journal of Very Important Studies, it is rarely to your detriment (you are pursuing a PhD, so they already know you have suspicious scholarly tendencies) and it keeps your options open. A scholarly publication can still serve as a mark of prestige and a demonstration that you are able to complete projects, have some authority in a field, and can engage with other authorities as a peer. Scholarly publications are particularly valuable for quasi-academic and research-oriented positions where there may be no expectation you will conduct research of your own, yet it makes people feel good that you’re published and thus must “understand our world.” It also preserves your academic career options (something we encourage in chapter 8), since scholarly publications are critical to being considered seriously for an academic position.

Table 6.1 Assessing the strategic benefit of publishing opportunities

Will this primarily draw from my existing expertise and knowledge (including my current dissertation research)? |

Existing: 20 points “In a way”: 5 points No: −10 points |

Will it be published in an outlet read by the people that I want to read it? |

Yes: 15 points No: −10 points |

What is the likelihood of acceptance? |

Pretty good (it has been solicited or discussed with the editor): 10 points Crapshoot (most unsolicited submissions): 3 points Equal to being struck by lightning: −10 points |

Money: Will I get paid for this? |

Yes, big bucks: 20 points Yes, but not much: 7 points No: 0 points |

Impact: What sort of impact/resonance do I expect from it? (Be honest.) |

Pivotal and long term: 20 points Will add to general knowledge and debate: 5 points People will talk about it, but only for a week: 0 points Probably not much: −5 points |

Time: Will the total amount of time to do this be measured in hours, days, weeks, or months? |

Hours or days: 5 points Weeks: 0 points Months: −20 points |

Leaving aside money and impact, am I excited about this publishing opportunity? |

Totally: 12 points It’s worth a shot: 3 points No: −10 points |

Scoring (should I pursue this opportunity?) |

|

Below 15 |

Never |

15–40 |

Probably not. Go back and double your scores (including negatives) for money, impact, and time and see if your score significantly improves. |

40–60 |

Maybe |

Above 60 |

Go for it! |

The good news is that writing a scholarly publication is perhaps the best education there is for understanding academic research. As you write, you are forced to condense your arguments and evidence into a specific word count, often 6,000–10,000 words, which focuses your writing style. This forces you to be very clear about your theoretical contributions and to state these explicitly and forcefully. The process also requires you to reflect upon and justify your methodology, and to acknowledge its limitations. While you can hide numerous flaws in a 300-page dissertation, a stand-alone article is so bare-bones that the problems of your research are easy to see. This sounds intimidating, to be certain, but once you have a draft article and can see these problems for yourself, you are in a position to address them, resulting in better research overall. The writing process also makes you a better reader and critic of other people’s published research.

Writing a scholarly publication also forces you to push beyond writing for familiar audiences (your professor, your supervisor, your doctoral committee) to writing for strangers. It requires you to look at your work with a cold, dispassionate eye—just as a future human resources officer or hiring committee will someday look at your job application. Again, this can be intimidating and requires a certain degree of bravery. But it does get easier with time, and through the process you learn not only how to anticipate how you and your work are perceived, but also how to focus on what is and is not within your power. In academic journal article publishing, you will quickly learn to make the submission of the journal article, rather than the acceptance of the article, your primary goal: You have no control over whether the article will be accepted, but you do have control over whether you complete it and submit it, and over how you respond to the feedback you eventually receive. This lesson to focus your energy and attention on areas where you have agency carries over to applying for jobs in academia and in other sectors, and it will serve you well in the long run.

Are book chapters or journal articles better?

Journal articles.

Oh, sorry—you wanted more? While some disciplines certainly value entire books over journal articles, and both book publishers and journals vary enormously in quality, journal articles are on balance definitely more valuable than book chapters because (1) they stand alone as individual author-initiated submissions and (2) they (normally) depend on double-blind reviews where you don’t know who the reviewers are and they don’t know who you are. This stand-alone, arm’s-length relationship is the gold standard of scholarly publishing. In contrast, and as we say in more detail below, edited books may be rigorously reviewed by editors and may go through a single-blind review with anonymous reviewers, but they do not have the same arm’s-length relationship and stand-alone merit of a journal article. Journal articles are also more accessible online and in search engines, giving them greater visibility and potential impact. We talk about the strengths of book chapters below, but make no mistake: On balance, articles almost always have more career value.

How can I get a journal article published?

There are typically three main steps to journal article publishing, which are outlined in the following sections.

Step 1: Choose wisely

All journals display certain patterns and parameters, not just in disciplinary fields and subjects, but also methodologies, writing and organizational styles, and audiences. Your journal selection determines both the audience you are writing for and the article’s structure (including length). The question of how to select your target journal can be complicated. Aiming too high for the top journals in your field can be risky as the chances of getting published are low; journal rejection can be crushing (we don’t use that word lightly) to even the most seasoned academic authors, and the process takes time. On the other hand, you don’t want to underplay your work by only considering the lowest hanging fruit. The best place to start, we suggest, is by identifying journals where the scholarly conversations in your niche area are occurring. For each, ask yourself, “Can I reasonably, truly imagine my article appearing in the journal and being of interest to its readers?” If so, the journal is a worthy contender.

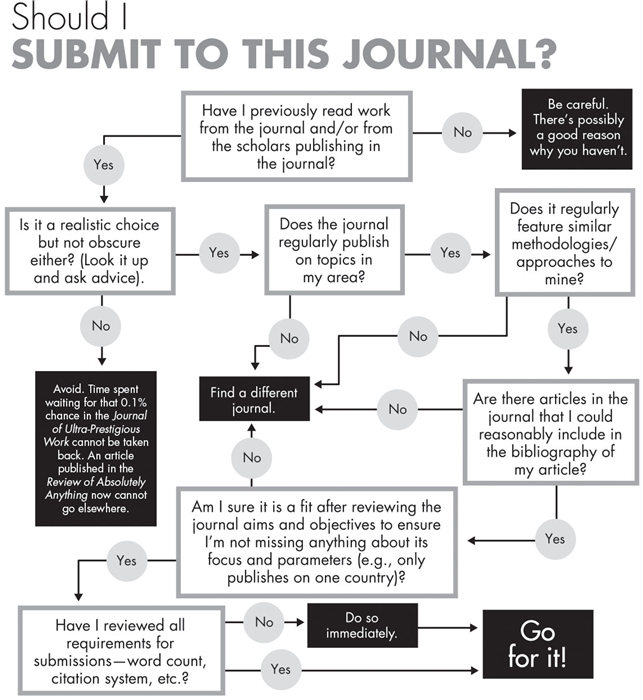

Figure 6.1: Should I submit to this journal?

What are predatory journals?

An entire shadow industry of predatory journals and vanity presses exists solely to “publish” academic work for a fee and allow people to add dubious entries to their publication list. While a few fall into a grey area between reputable and predatory, most outlets are obvious with their aggressive solicitations and “quick review and publication” promises. Publishing with these can have major reputational consequences, suggesting you are either naïve and gullible or you knowingly published in a disreputable location to pad your cv. Neither will aid you in reaching your career goals. The good news is that it does not take a great deal of due diligence to avoid these outlets if you do a little research and ask around.

Step 2: Create structure

Journal articles often follow a formula. This formula will vary according to discipline, methodological tradition, and sometimes even the journal itself, but if you study your target journal, you should see a general pattern. How long do introduction, literature review, analysis, and conclusion sections tend to be? Emulate the structure you see in the journal, particularly for articles similar in topic or method to your own. After it is written, have a trusted person help you proofread it and ensure that you meet the journal’s style guidelines. Then, when you feel it is ready, send it in.

Step 3: Lick your wounds and move forward

Your submission is unlikely to be accepted on the first try (if it is, keep your lucky streak going and head to the nearest casino) and will likely receive one of two responses: rejection or revise and resubmit. Chances are also good that, regardless of which response you get, you will receive some feedback that seems harsh. It will sting. All of the voices in your head (at least one of which sounds like that person, your graduate student nemesis to whom everything comes so easily) will be quick to tell you that this rejection is a clear statement of your worth, your abilities, and your terrible, terrible choices. Your research question is boring and irrelevant, you should have used different data with better analyses, your work is theoretically deficient, and your writing is sloppy. Also, you could be cuter, or at least better dressed.

Rejection

The best thing to do with a rejection is to wait a few days. Once the worst feelings have passed (and they will pass), you need to assess the feedback. If you received a “desk reject,” in which the editorial team decided not to send your paper out for review, consider if it occurred because the journal was a poor fit or because the contribution of your paper was unclear. Typically, the editor will provide you with a small amount of feedback about why the paper was not sent for review, but it is extremely limited (and frustrating). If you received a rejection based on the editor’s assessment of the journal reviewers’ comments, you have the advantage of peer feedback in the form of the editor’s summary comments and the reviewers’ detailed comments.

It is important to take the time to think strategically about your next steps. Unless you are truly convinced that the work should never see the light of day, make the commitment to rework the material and get it back out there. Keep your end goal in mind: an article that can be part of your strategic publishing portfolio. The only way to do this is to get your article back out and under review. Find a second journal to submit your work to, then ask yourself whether this journal is truly a good fit for your work, and if so, what changes are necessary to fit the journal structure and style. You also need to ask yourself if the merits of the paper are easily apparent to the editors and reviewers. If you have received detailed feedback, you need to assess which comments merit changes to your work, which comments suggest a misinterpretation of your work that require you to communicate your ideas more clearly, and which comments are best saved for rants to close friends about how terrible peer reviewers are.

In making these assessments, including the decision on whether or not to move forward with the article, you ideally will have someone you trust that you can discuss these matters with. Your supervisor seems like an obvious choice, but there may be other individuals who can assist you. Be sure to select someone who has experience with journal article publishing and who will provide you with constructive advice (as opposed to cheerleading or copy editing).

Revise and resubmit

If you are given the opportunity to revise and resubmit back to the journal, get to work on it immediately. Make yourself a schedule and establish a plan to do everything you can to address the reviewers’ comments. It is helpful to create a table with three columns: reviewer, comment, response (see sample provided in Table 6.2). If a reviewer’s comment is even remotely reasonable, try to find a way to address it. If it is not reasonable, try to find a nugget within it that you can work with. If it is completely unfathomable to you that any change whatsoever be made in response to the comment—and if you are certain, truly certain, that you yourself are being reasonable— then find some way to politely and respectfully explain why you are unable to accommodate that particular change.

The next critical step is to respond directly to the reviewers and to every single comment. If they write something flattering (“This paper is well written.”), the response is gratitude (“I thank Reviewer B for this positive assessment.”). If they recommend including a particular body of literature, explain how you incorporated this literature. You will send all of this to the journal editor along with the revised manuscript. The amount of detail you provide in this revision table may seem overboard, but it is necessary to demonstrate both to the reviewers and, more importantly, to the editor, that you have taken the critiques seriously.

Table 6.2 Reviewer response table example

Reviewer |

Comment |

Response |

|---|---|---|

Reviewer A |

“I was not convinced that X leads to Y.” |

In the revised manuscript I provide the following two additional sources of evidence to support the claim that X leads to Y: … |

Reviewer B |

“I am disappointed that the author has made no reference to the extensive work of Smith.” |

I have added references to the work of Smith, clarifying that her work applies to daytime while my focus is on night. |

Our experience: Loleen

When I was a PhD student, I sent a paper into one of my discipline’s national journals. It was a sole-authored work and related (albeit not as directly as we recommend) to my dissertation topic. I received a revise and resubmit, which I now with hindsight consider to be an encouraging outcome. At the time, however, I was daunted by the work required to meet the reviewers’ comments. My supervisor, to his credit, told me that I should resubmit, but I failed to do so within the three-month resubmission window. Looking back, I regret that choice. While the resubmission may or may not have resulted in a publication, I deprived myself of the learning opportunity.

Should I write a book chapter for an edited book?

Maybe. Probably not.

This is different from a sole or coauthored book, which in many disciplines is the highest goal. But edited books have a mixed reputation. There are field and methodological landmines here, as the format of stand-alone journal articles may seem to fit certain types of scholarship that are easy to break up and present in 8,000 words with no further context. Work that is more theoretically complex, interdisciplinary, or otherwise does not fit neatly into existing patterns in the field may be better served as part of a broader collection of similar chapters that together make a more coherent whole. Yet while edited books can be great things for scholarship, their career value is shakier. The above factors mean that book chapters inevitably have a reputation as repositories for work that isn’t strong enough for a journal article, which as we said above will always have a higher rank because of its stand-alone processes. And many academics see book chapters as the jury duty of scholarly life: undesirable, but nearly impossible to turn down when summoned. Thus, while book chapters are not bad and may be the best way to publish particular kinds of work, they have definite risks and costs that may outweigh the benefits.

One of the largest risks is time. The edited volume may never see the light of day, or may ultimately be published years (sometimes many years) later than the editors originally promised or hoped. Peer-reviewed journal articles typically have a quicker turnaround, and articles are often made available online far in advance of the actual issue date. Decision making in journals is also more straightforward. Though articles typically go through at least one round of revisions and can be at the mercy of slow reviewers, the article is ultimately either accepted (sometimes conditionally, with clear steps to resolve the conditions) after which it enters the production process, or not accepted. An edited volume, by contrast, will have several stages, even if you’ve been invited to contribute with the implicit presumption that the chapter is a sure thing. It will likely go through one or more rounds of revisions with the volume editor, followed by a further round of revisions through the publisher’s peer-review process, and only then does the publisher make a final decision, which may be influenced by commercial as much as scholarly reasons. If the project starts with a workshop or conference for contributors, that means an additional stage of presentation and feedback, which is good for the work, but it stretches things out even longer. Hence, promises of a “forthcoming” book chapter are sometimes viewed by academic hiring committees skeptically. Journal editors, required to make regular decisions, will also be more on top of the job than most frazzled book editors (see below on why you should not edit a book at your career stage). Opting to contribute your work to an edited volume rather than a journal risks that the work may languish for years before (possibly) seeing the light of day. In that time, the work could have been published elsewhere, informing scholarship, amassing citations, and building your own résumé and CV.

Nevertheless, there are benefits to a book chapter. They are scholarly publications after all, and being part of an edited collection can be an invigorating experience. A cohesive and path-breaking book can lead to more exposure than an isolated journal article and give you opportunities to publish work that indeed does not fit easily in journal article format. Participating in an initial workshop is especially rewarding, as your work will receive far more attention and informed criticism than any conference panel, and you’ll have an opportunity to meet and interact with other people in your field (ideally at all stages of career). And a good book editor who knows your general field and knows what they are doing will be a joy to work with and make you a better scholar. Appearing in a good edited collection—especially alongside some big names—makes you look good, and if the book is a hit, more people will come across and remember your work in the collection than the average journal article. Finally, as mentioned above, the journal article format can favour some types of scholarship over others. An edited collection can allow contributors to play to different strengths and tackle different theoretical, methodological, and empirical angles as a collective, rather than having to hit all the bells on their own. So book chapters definitely have their merits, especially for new forms of research and interdisciplinary research. Having said that, at the dissertation stage, your work should be hitting all the necessary theoretical, methodological, and empirical bells and hopefully can be published accordingly. Book chapters are best left for later in your career when you want to explore new areas and have the opportunity to be part of something bigger.

Our experience: Jonathan

For years I researched the politics of evangelical Christians in Canada, but I had much more success publishing this research as book chapters or in invited special journal issues than through stand-alone journal articles. A constant problem was that the topic straddled disciplinary and methodological boundaries, and existing research was very American-centric and difficult to build on either theoretically or empirically. This left everything very open ended without firm boundaries, and I struggled to package work into 8,000 stand-alone words that would satisfy reviewers. In contrast, edited collections provided a coherent overall framework in which my work could be one part of the puzzle, without needing to tie up every angle. But journal articles still would have been better for my career.

Should I edit or co-edit a book?

No. Editing a book seems like such an easy thing before you get started. In the shiny, optimistic vision that you can picture so clearly, the contributing authors will submit their chapters on time, at a high standard. You will develop important contacts with important people, and these relationships will advance your career. You will get to know publishers, who will be there for you when you are ready to publish your PhD dissertation in monograph format. Future employers will see the edited book among the many accomplishments on your CV or résumé and single you out for job interviews. And above all else, it will be easy and fun and just come together naturally. Plus your name will be right there on the cover, for all of the world to see!

We hope that our skepticism was evident in that last paragraph, but in case it was not, here is the reality: Editing books is a bad choice for pre-tenure academics generally and for PhD students in particular. As we have already explained in our discussion on book chapters, edited books are an uncertain business at the best of times. You simply do not have the time to devote to uncertain, potentially stressful projects that do little to advance your publishing portfolio. Add to this the potential relationship costs (do you, as a graduate student, really want to be badgering a senior scholar about a chapter that is three months late?) and the advantages (if they existed) of editing a book evaporate.

If you still decide to go ahead with plans to edit a book, make sure to not leave yourself beholden to particular chapter authors (e.g., a book that includes a chapter on each Canadian province, with only one particular specialist available to write the chapter on Prince Edward Island). Your life will become hell.

Should I coauthor?

Probably, but (probably) not exclusively.

Norms vary dramatically by discipline (and even subfield) here, with sole authorship being the overwhelming norm in some disciplines but multiple authors being the custom in others. Relatedly, some disciplines have a strong expectation of supervisors co-publishing with their students, while in others this is exceptional. You probably already have a good idea where your discipline or supervisor fits on these scales.

If sole authorship is common in your discipline, we’ll note that there are many advantages to working with a coauthor. First and foremost, if you work with a good supervisor or mentor who considers the coauthorship a form of career mentorship, you stand to learn a significant amount about scholarly writing and in a constructive manner. Second, coauthoring can be more efficient than sole authoring, allowing you both to build your publishing portfolio and to increase your profile as an expert in the area more quickly. Third, successfully coauthoring work provides you with evidence for future employment claims that you can work well with others. However, all this depends on finding a suitable collaborator. You may have little power over your supervisor’s choice to coauthor with you. But you may find opportunities to approach them or another mentor with a specific idea. And you certainly have agency to seek out peers, especially fellow students, to work with.

On the other hand (though your discipline may have a different dominant view here), you should ideally publish at least one journal article on your own. You want to clearly demonstrate to future prospective employers that you are able to independently make an intellectual contribution, to independently complete work projects, and to independently write at a high-quality level. The use of the word “independently” in triplicate in the last sentence hopefully drives home the point that coauthorship can raise uncomfortable questions for prospective employers and creates undesirable ambiguity about your exact contribution and capability. If you publish with your supervisor or other mentor, a search committee or human resources director is torn. Did you do most of the work? Were you more a research assistant than intellectual collaborator? Or was it a genuine partnership of equals? It could be any of the above, and it is difficult to know. The questions may be fewer if you publish with your peers, where there may be a presumption of a more balanced relationship and genuine collaboration. But even here you have not clearly and irrefutably demonstrated your ability to work independently (yes, we used that word again).

If I do coauthor, how do I make it work?

Coauthoring can lead to almost any outcome: a highly positive experience, a highly negative one, or any point in between. In many ways, it is analogous to taking a road trip with someone: Even if you think you already know them fairly well, by the end of the trip you know far more than you ever expected to … and in some cases hoped to. We could belabour this analogy by referring to disputes over who should drive, whether or not the passenger is contributing in a meaningful way, and whether the washroom pitstop was overly long, but as this will prove tedious, let’s move on to some practical advice.

Successful coauthorship comes down to expectations and communication. When coauthoring, you need to pay attention to who needs (or wants) the publication more. There are power dynamics at work in most relationships, and that is true in authorship as well. Often, there is one individual who is more committed to and motivated by the project; this person might be the principal investigator on the grant funding the research, or a graduate student seeking to add to their CV. While you don’t need to have an explicit discussion about the topic (“Mark, I feel I care more about our paper than you do …”), in your own head it can be useful to clarify whether or not you are the driving force behind the work or not. If you are the person who wants the publication more, expect to do more (in some cases, almost all) of the work. Yes, this may seem unfair, but (hopefully) you are still getting something out of the partnership, such as strategic insight or data access, to make the coauthorship worth it. If you are the person who wants the publication less, you need to be careful that your lower motivation doesn’t result in you failing to fulfill your commitments, thereby damaging the relationship.

Clear communication is key in coauthoring. The business adage of “underpromise and overdeliver” applies here. If you realistically think you can get the work to your coauthor by October 15, promise it for October 31; in the best case, you impress them with your efficiency, but if something comes up that pushes your schedule back you have some extra time to meet the deadline. Here we refer you to chapter 7 and suggest you build these coauthorship commitments into your schedule in a realistic fashion. If you find that the scheduling exercise leads you to conclude that you have taken on too much and cannot reasonably expect to meet particular timelines, let your coauthor know as early as possible, and if necessary offer to withdraw from or take a lesser role on the paper.

I am at the end of my program and didn’t do any of this. What do I do?

As always, it is never too late. First of all, if you have completed or are about to complete your dissertation, start thinking about what you can do with it. Could it be published as a book? As a series of articles? While the process takes time, effort now could yield happy things later, and if you are interested in an academic job, scholarly publications are vital. In addition, review the first part of this chapter and the wide world of publishing beyond scholarly outlets. We remind you: Somebody somewhere is looking for your ideas in written form. While a scholarly publication has inherent value regardless of your career goals, those goals may be better served at this point by looking primarily at other types of publishing that can emerge much faster and establish your professional credibility. And you can still work on that submission to the Journal of Never Too Late Studies, because that will also advance your goals. Publishing is ongoing, and once you get started, you will get in the groove.

So, bottom line, what should I do about writing and publishing?

We started this chapter by describing the publication arms race in academia. We urge you not to focus on somehow winning that race by producing more than anyone else, but to see publishing as a wider goal that spans different types of publishing and builds and illustrates your overall skills and expertise. We believe you should do the following: (1) start publishing during your PhD program; (2) focus on a select topic for which you seek to be known; (3) think widely about all kinds of publication outlets while prioritizing scholarly publishing; (4) be highly selective in your writing outlets and highly conscious of the opportunity costs of different options; and (5) consider coauthorship as a supplement to (rather than a replacement for) sole authorship. You will ideally leave your PhD program with a publishing portfolio that demonstrates your ability to complete projects, meet scholarly standards, work independently, write for diverse audiences, and contribute substantive information in your area of expertise. And it always looks great to see your name in print, and no one—arms race or not—can ever take that away.