11

Spans and Layers

Flatten and Empower the Organization

Restructuring the spans and layers of management control within a company is one of the most effective tools for addressing organizational bloat. This lever reduces organizational layers and management overhead, which not only cuts costs, but also simplifies decision making, improves flexibility, enhances responsiveness, and unleashes innovation—positioning the company for better growth.

What Is a Spans and Layers Restructuring?

Restructuring spans and layers optimizes two critical aspects of organizational structure: the spans of control (the number of direct reports for each managerial position) and management layers (the number of hierarchical levels that distance the front line from the CEO). A spans and layers analysis enables a company to identify and eliminate narrow spans and excessive layers.

In our experience, even the best-run companies tend to lose focus on their organizational structure over time, at least in some businesses or functions, and end up with too many layers and too much management overhead. This may result from poorly integrated acquisitions, unregulated growth, or simple inattention. Unless periodically reviewed and adjusted, unwieldy organizational structures burden a company with high management costs and stultifying bureaucracy. Excess management layers with narrow spans of control slow down decision making, delay the flow of information from the top to the front lines (and vice versa), stifle creativity, and frustrate employees subjected to micromanagement by supervisors who don't have enough management work to do.

Before reading further, take a moment to review Figure 11.1 , which illustrates management spans and layers, and defines key terms we'll be using throughout this chapter.

The “right” span of control for any managerial position depends on a range of factors. Particularly important is the complexity of the role—the scope and complexity of work overseen, the degree of judgment involved in day-to-day activities, the stability of work processes, and the amount of interaction with others within and outside the organization. Managers overseeing highly complex activities should have fewer direct reports, while those responsible for simpler functions can manage more employees without undue risk.

Generally, spans of control will range from 5:1 to 15:1 for most management positions. In transactional functions such as customer contact or accounts payable processing, each front-line supervisor can manage 8 to 15 line employees. The appropriate span for consultative roles, such as supply chain planning, finance decision support, and sales representatives, ranges from five to eight employees per manager. Expertise roles such as legal counsel, tax planning, or business development require a manager for every four to six employees (see Figure 11.2 ).

Wider spans of control force managers to focus on guiding, coaching, and managing, and empower individual contributors to make decisions and truly “own” their work. Wide spans also enable companies to reduce managerial ranks and eliminate layers of management. Reducing layers winnows bureaucracy, speeds up decision making, increases information flow up and down the organization, and brings senior management one or two steps closer to customers and front-line operations. With fewer midlevel managers clogging up the organization, accountability and transparency increase. Eliminating layers also pulls talented managers up from lower ranks, and improves career opportunities for others stuck in the middle.

In our experience, a range of benefits accumulate as management structures become more efficient:

- Employee engagement increases when decision-making authority devolves to front-line employees, micromanagement subsides, and opportunities for development and advancement increase.

- Decision making accelerates as information moves faster through a flatter organization, and cross-functional collaboration improves with fewer management layers in the way.

- Fewer managers means fewer meetings, resulting in less time spent on administrative meetings.

- Spending on salaried managerial staff declines by 10 percent to 15 percent as highly paid positions are eliminated and work shifts to lower-paid contributors.

For example, expanding spans and eliminating layers across an organization with 15,000 individual contributors will dramatically reduce management overhead costs. At an average span of control of 4:1, the company needs 5,000 managers to oversee 15,000 individual contributors. Doubling the average span to 8:1 means the company needs just under 2,000 managers for the same 15,000 employees—a 60 percent reduction in management overhead. At the same time, expanding spans of control reduces the number of management layers from seven to five, bringing top managers much closer to the front line.

When to Restructure Spans and Layers

How can you tell if your organization's spans and layers are out of shape? Look for these telltale signs of structural inefficiency:

- There are seven or more layers of management between the CEO and the front line.

- Managers oversee fewer than five employees on average.

- Decision making is slow and requires multiple levels of approval.

- Meetings typically include 10 or more people to assure that all stakeholders are represented.

- Bureaucracy is sapping morale across the company.

A dead giveaway is an organizational profile in the shape of an hourglass or an inverted pyramid (see Figure 11.3 ). In an hourglass organization, wide spans at the top and bottom are separated by multiple layers of middle managers with narrow spans of control. In an inverted pyramid organization, the picture is worse: front-line managers have the lowest spans of control.

Embedded in these structures is a tendency to manage by consensus and a fundamental aversion to accountability (or, in some cases, an unwillingness on the part of top management to hold their teams accountable). Overcrowded org charts insulate people from responsibility for delivering results and meeting commitments. Redundant layers of management encourage decision makers to protect themselves from the consequences of their choices. When spans of control are too narrow, even the most routine decisions require multiple managerial meetings. Mistrust flourishes and costs rise as highly paid managers do little more than attend meetings and “chaperone” employees through their daily tasks. Anxious to justify their own existence, managers burden subordinates with endless requests for information, reports, and other “make-work” assignments that leave lower-level staffers with less time for work of real value to the company.

If your organization fits these profiles, it's time to rethink your spans and layers.

How to Restructure Spans and Layers: Five Steps to a Leaner Organization

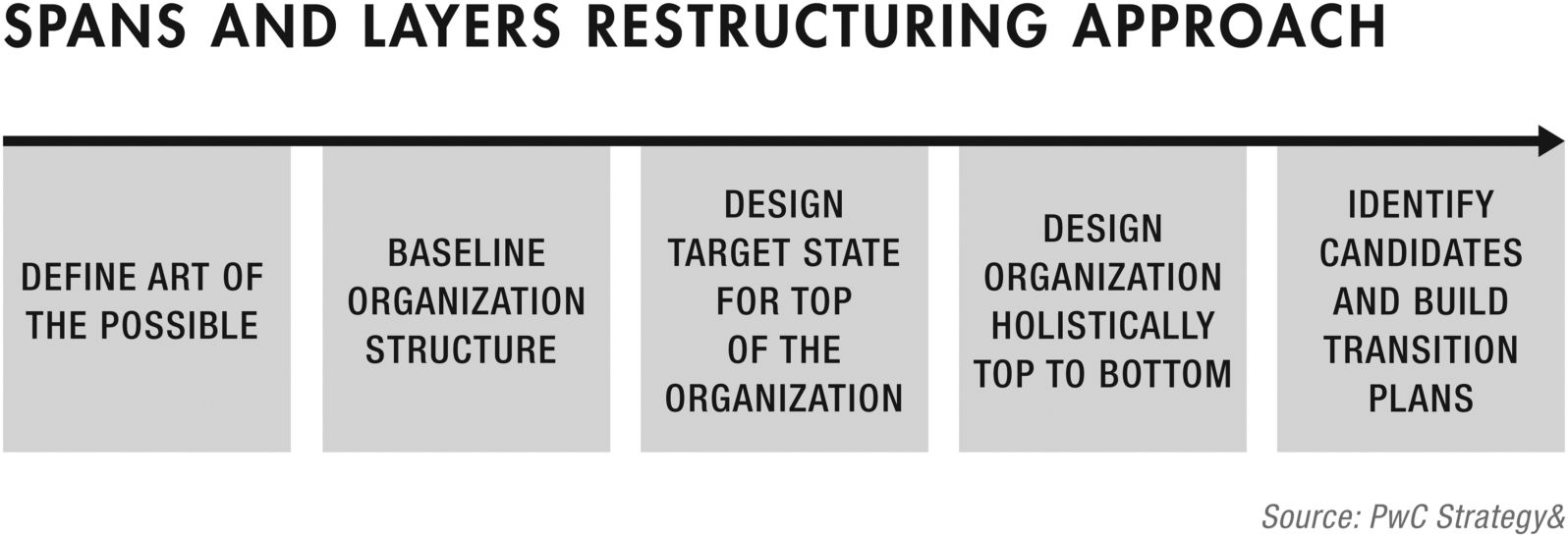

A spans and layers restructuring rationalizes management through a five-step process, starting with an “art of the possible” analysis that identifies all potential opportunities to expand spans and eliminate layers. From there, the process moves through baselining to redesigning upper management, functional hierarchies, and the rest of the organization, followed by transition planning (see Figure 11.4 ).

Step 1: Define the Art of the Possible

An exercise we call “the art of the possible” will reveal the full potential scope of a spans and layers restructuring of your organization. This top-down, analytical exercise highlights narrow spans of control and redundant management layers. It quantifies potential savings from expanding these spans of control and consolidating redundant layers. The art of the possible review comprises two main elements: an evaluation and breakdown of organizational hierarchies based on data from human resources information systems, and a comparison of spans and layers against appropriate functional benchmarks.

Rarely does an organization capture all the potential savings identified by the art of the possible exercise. A variety of risks and other practical factors limit the actual scope of most spans and layers restructurings to between 60 percent and 80 percent of the theoretical opportunity.

Step 2: Baseline the Organizational Structure

After completing the art of the possible analysis, develop a set of options for senior decision makers. Guide their deliberations with organizational charts highlighting low spans of control, a top-down analysis with cascading targets for spans of control at each level of the organization, point-of-view hypotheses for meeting span guidelines at the second level, and scenarios for eliminating management layers throughout the company.

Step 3: Design the Target State for the Top of the Organization

Work with the CEO to restructure upper management, designing logical, coherent operating models for functional organizations and business units. Consolidate major areas of activity by region, work type, or some other commonality that creates potential economies of scale across your operations. This top-down exercise moves beyond mere cost cutting to focus on organizational coherence. It yields insights that can guide later design choices, and helps senior leaders confront difficult decisions that may eliminate the positions of longtime colleagues.

Using the CEO's upper-management redesign as a blueprint, help executive leaders rationalize spans and layers in their organizations. Bring these executives together in joint design sessions to discuss possible consolidation of like activities across departmental lines, and challenge existing segmentation of work that isn't based on rational distinctions. The joint sessions also will reveal opportunities to accelerate decision making, highlight potential “quick wins,” and identify top talent for leading roles in the restructured organization.

Step 4: Redesign the Rest of the Organization Holistically

Restructure the remaining levels of the organization comprehensively, rather than layer by layer. A holistic approach extends the coherence of your upper-level redesign throughout the company (see Figure 11.5 ). But rather than relying solely on upper management for guidance, it draws on insights from leaders at lower levels. They often have a better understanding of the rationale for existing management structures, and greater familiarity with the regulatory considerations, customer requirements, and other practical impediments to consolidating layers and expanding spans of control. Tapping a broader knowledge base also surfaces more opportunities to drive efficiency. Just as important, a comprehensive redesign prevents the talent drain that often results when a layer-by-layer restructuring discharges managers in successive waves, which can demoralize—and even paralyze—the whole organization. Instead, the company's entire talent pool is available to fill all management positions in the new organizational structure.

As you redesign your organization around new spans and layers targets for each function, your operations may have to change as well. For example, expanding spans of control may require consolidation of decentralized activities, standardization of common business processes, and upgrading of management talent to manage a diverse set of processes. Consolidation and centralization, however, will eliminate layers of management, bringing P&L leaders closer than ever to the people who actually do the organization's front-line work. In parallel, strive to whittle down redundant levels of hierarchy above the natural business units. This may require eliminating management layers that were set up to manage risks, handle process exceptions, or create placeholder slots that provide regular promotion opportunities for lower- and middle-managers. Delayering also may elevate some roles and downgrade others: a senior management slot may move down a rung, while a midlevel role moves up.

Your organizational redesign should also include a reevaluation of seniority levels for each management position. This is an opportunity to combat the title inflation so common in the corporate world. You may find, for example, that a vice president's role could be assigned to a director-level manager with fewer years of experience but a strong grasp of the organization and its operations. In other cases, you will have to decide whether business objectives are best served by expanding a manager's span of control, or by creating a “player-coach” role for a manager who will perform work as an individual contributor while supervising and guiding others.

Redesigning your organization and streamlining management also requires defining new roles, responsibilities, and decision rights across the company. Often the most uncomfortable part of the adjustment process, this is also the most important thing you can do to ensure your new organization operates effectively. A well-designed and streamlined organization gives more decision-making authority and responsibility to managers accustomed to managing by committee. Clearly defining these responsibilities and decision rights—and linking them to performance criteria—is critical to success.

Step 5: Identify Candidates and Build Transition Plans

You'll need to redefine management roles for an organization with fewer management layers and broader spans of control. Rewrite job descriptions to suit these new requirements, and launch selection processes to find the right talent for managerial positions that may call for different sets of abilities. Also, prepare transition plans that identify the managers displaced by the reorganization, and outline redeployment strategies for those who will be transferred, temporarily retained, or terminated.

Intensely competitive global markets require flexibility and rapid responses to ever-changing conditions and customer preferences. Out-of-shape companies can't move fast enough to capture fleeting opportunities and neutralize onrushing threats. Restructuring spans and layers to eliminate unnecessary bureaucracy will not only reduce costs, but also give your company the flexibility and quickness to win in this ever-changing business environment.

- Avoid the allure of simplistic targets. Beware of targets such as “no more than five management layers” or “no fewer than five direct reports.” Not all spans are created equal. Sustained improvements hinge on developing the right size and number of organizational building blocks for your organization, based on core business processes involved, the type of work, and the interactions required to drive smart decision making.

- Create fit-for-purpose targets. Base targets for management spans of control on the nature of the work, the type of supervisory role, and decision-making responsibilities.

- Start at the top. Work with the CEO to redesign the top three levels of the organization. This allows the CEO to shape the organization, create a model for others to follow, and short-circuit political interference. Redesign the rest of the organization holistically, to ensure a coherent structure, maximize efficiencies, and capitalize on insights from people at all levels of the company.

- Implement measures and incentives. Aim to sharpen the organization's focus on accountability and the consequences of hitting or missing performance goals.

- Design fulfilling career paths. Staffing strategies, including horizontal moves and increased compensation, should challenge and reward managers faced with fewer classic upward promotion opportunities.

- Deprogram micromanagers. Train the next generation of middle managers to delegate more decisions to the front lines, where relevant information resides.

- Modify job titles and compensation levels. They should reflect and encourage simplified and streamlined work processes.

- Institutionalize communications vehicles. They should break through traditional roadblocks that impede the free flow of information.

- Adhering to benchmarks that don't fit your company. Industry benchmarks are just a guide for sizing up potential opportunities. Actual program goals should be based on customized benchmarks reflecting the complexity and risks of your business.

- Confusing operational experience with decision-making acumen and accountability. Establish clear decision rights and accountabilities for every management role.

- Failing to distinguish management activities from activities performed by managers. People with managerial titles (and paychecks) frequently do the same work as those they nominally supervise.

- Naming names. Spans and layers should be an objective exercise focused on roles, not individuals. Don't introduce subjectivity by putting names in boxes as you plan your new organizational structure.

- Hearing too many voices. When too many people participate, every management post is defended. Remember, spans and layers isn't a democratic process. It's a top-down initiative that should be driven and controlled by senior management.