New Screens

Donna Haraway (2008) has a wonderful essay on Crittercam, a National Geographic show where cameras are attached to animals in the wild. Following the work of Don Ihde, she talks about the infoldings of technology and animal, and also viewer and screen, and of course the asymmetrical infoldings of viewer, technology and animal. The implication of this assemblage (my term, not hers) is, for Haraway, “epistemological-ethical obligations to the animals” (263). I don’t want to rehearse Haraway’s subtle analysis here, but point to three aspects of mobile screens implied by her analysis. First, we need to consider the relation of self to screen, in this case, the screen in the hand, both furtive and controlling (us watching). Secondly, we need to consider the materiality of the arrangement of camera and subject. The camera is embedded in a landscape; the camera is surveilling a place of business or leisure, with broader implications and articulations to state-sponsored civic traffic infrastructure, organizational self-surveillance, and so on. Third, the articulations through networks of communication and computing that link one to the other imply an ethical responsibility. This means that in viewing these images I am participating in the surveillance at the other end. These three aspects are a part of this assemblage of attention: our attention to the screen in my hand, the attentions of the remote camera, and the myriad devices, processes and relationships established to articulate one to the other.

Body-to-Screen

A Screen in the Hand

We begin with the infoldings of hand and screen, and the production of the experience of attending to the screen. What has been called the phenomenology of the mobile screen is an expression of this assemblage.

In 2000, while walking in Tokyo, writer Howard Rheingold (2003) recognized a new shift in the technological everyday when he realized that some pedestrians weren’t talking on their mobile phones, but staring at them. In my own terms, he was noting a shift in the technological assemblage, especially urban street culture. The urban pedestrian has a particular way of being in and negotiating the space of the city street that is always technologically inflected. Such assemblages are also continually shifting with social, cultural, economic and technological transformations. From the flâneur of the nineteenth century assaying the newly electrically illuminated street, to the privatization of public space made possible by the Walkman in the 1980s, to the opening up of local spaces to elsewheres through the constant communication of the mobile phone, each articulates bodies, technologies, epistemologies and phenomenologies: ways of embodying space. The altered relation of the subjects with their environmental contexts can be noted by changes in gesture, position and attitude. Pedestrians with portable music players stare into space, not making contact with those around them, an attitude continued by people on their mobile phones (attending to a space neither here nor there, but the space of the phone call) (cf. Bull 2007). The attentional gravity of a phone call is to the space of the call which is always other than the physical space that we are in, though we do vaguely attend to that as well. It is not a question of either/or (mediated space or physical space) but the grasping of both, like a form of stereo vision, what Paul Virilio (2000) called stereo-reality.3 What Rheingold noticed was rather than people walking with one hand clasping a phone to their ear, people were looking at their phones. The phone itself becomes a strong point of visual attentional gravity. These people were, of course, texting: typing and reading short messages. Rheingold was noticing this new behavior in its early days, before it had become habit. Soon texting was to become habitual and haptic, that is, performed through feel, not vision. Though the phone in the hand remains a crucial component of the contemporary pedestrian (indeed, they tend to be constantly in our hands like large worry beads—Plant [2001]), they eventually became more the subject of our haptic attention than our visual attention. However, as Cooley has argued, haptic and visual attention are not mutually exclusive, indeed the phone in the hand seems to transform what and how we see (Cooley 2004).

The questions of this chapter are as follows: if one function of a television screen is to look through it (rather than at it); that is, if a live television image transports us phenomenologically to an elsewhere (in a way quite different from the aural elsewhere of a phone conversation), what do we make of the phenomenon of live video images held in our palms, the result of mobile television and webcam applications? There is a hole in one’s hand, and how does the hole in one’s hand implicate us in extended assemblages of care and control?

The phenomenology of mobile media devices is being mapped by Ingrid Richardson (Richardson 2005; 2007; 2011; 2012; Richardson and Wilken 2009) and others (see, e.g., Farman 2012). So let me touch on some relevant findings. Note, however, that most of these scholars take mobile locative gaming as their object of study, rather than webcams or video viewing. Richardson observes that these screens are only glanced at, usually used in the context of other activities, momentary and interruptible. Content for mobile television, as a Nokia report put it, will be “snackable” (Orgad 2006), designed to fill those distracted, in-between moments. The notion of a person consuming media in distraction is not a new one, by any means, and certainly not unique to these devices—though, perhaps, there are a greater number of sources of distraction today. Walter Benjamin and Sigfried Kracauer noted in the early decades of the twentieth century that reception in distraction was one of the hallmarks of modernity (Highmore 2010). Distracted consumption (which means both a fragmented distracted object of consumption and the scattered attentional state of the receiver) is said to short-circuit critique and thought—we’re not concentrating, after all (cf. Benjamin). But also, it is said to provide opportunities for critique. Reception in distraction tends to sit at the level of habit, the everyday, more a part of the rhythms of our bodies, their spaces, and their days than consciously decoded meanings and communications (see. e.g., Bull 2007; Highmore 2005; Lefebvre 2004).

Richardson also notes the intimate nature of hand-tool relation—mobile phones, for example, are habitually held; they are extensions of our hands, part of our body schema. These screens are not just visual and aural, but haptic. A key way we interface with the phone is by touch—not just dialing numbers but by texting. Larissa Hjorth argues that the “haptic has often been under-theorized in mobile communication discourses” (2009, 145).

Studies of other mobile devices have examined further this relationship of hand and screen. What Heidi Rae Cooley (2004) has termed “tactile vision,” Nanna Verhoeff (2009) refers to as “haptic visuality” in her study of the Nintendo DS (dual screen) mobile gaming system. In the DS one manipulates the image and gameplay by touching a second screen with finger or stylus (comparable, though more intimate, to the mouse-screen interface of the desktop—the mouse is further removed from the action than the finger or stylus.)

A step past the DS is the direct manipulation of the image on screen by touching that screen (and not a secondary one). This, of course, is the iPod/iPhone/iPad interface. What differentiates the haptic interface of the iPhone from that of previous mobile devices is first the relation to the hand—it fits less comfortably than rounder, smaller mobile phones. More crucially, however, is the lack of buttons (beyond the one). Most interaction is done via the screen. But the screen could display anything–numbers, a piano keyboard, or playing cards. That is, unlike previous phones described by Richardson, the affordances of the iPhone require us to look—the surface feels the same and there is no tactile differentiation between applications (which, a contributor to this volume, Gerard Goggin [2006], has pointed out is an issue for those who cannot see).

A key feature of the device is its visually directed haptic interaction. Icons are moved, images stretched, objects manipulated by directly touching them on screen, not secondhand via a stylus, mouse, keyboard or secondary screen. We should not underestimate the sense of control this brings. There seems to be no intermediary. Even though we get used to the spatial dislocation of mouse and screen, and directly manipulate images in front of us on a desktop computer by moving the mouse at some remove from that image, it is much more powerful to reach out and (seem to) do it ourselves with our own hands. This particular sense of agency is an important part of this new assemblage.

We seem to be poised to take another step—the screen moving out of the hand and up to the eye itself, in the form of Google Glass (cf. Wise 2012b, 2013). Control of Glass is hands-free, for the most part, relying on verbal commands and head motions, and potentially even blink patterns. The device overlays a small screen in the corner of your vision. Screen and environment are both constantly present, a literal version of Virilio’s stereo-reality. The phenomenology of such devices is too new to speculate (for clues, see Steve Mann’s work [2001], since he’s been experiencing this for decades), but the transparency of video punches a hole not in one’s hand, but in the world.

Seeing Through

Bolter and Grusin (2000) differentiate between transparent media and hyper-media. Transparent media are those we seem to see through; the devices themselves disappear. Many of our common communication media such as telephones and televisions are transparent. Hypermedia, on the other hand, are displays that draw attention to themselves—we delight in the virtuosity and spectacle of the surface, but don’t expect to be transported through to anywhere else. We look at them, not through. Many of the joys of the iPhone and iPod touch are precisely apps that are hypermediate. The point is to play with the surface whether it’s manipulating a photograph or moving an image of a paddle in an air hockey game.

Verhoeff likewise notes the transparency of some screens, but contrasts them with opaque media. What’s important for Verhoeff about opacity is that it emphasizes—following Bill Brown’s work—the thingness of the screen, the materiality of the device. The thingness of the screen allows our relation with the device to remain haptic and habitual, but resists the device’s complete disappearance into transparency.

There are a number of dangers when devices disappear. For example, we lose the ability to interrogate their place in our lives once they become taken for granted, part of the woodwork (Wise 1997). We will consider these implications toward the end of the chapter.

Lefebvre’s Windows

These properties of the mobile screen (including consumption in distraction, relative privacy, in the hand/under control, visually engaging, prone to hypermediacy) depend on the practices in which these devices are involved, the types of images engaged with, and so on, rather than the device in and of itself. So, for example, webcam applications differ from, say, Angry Birds, in that they are applications of transparency, not opacity. Hence, my title: a hole in the hand. When one looks at a live, streaming webcam image, the screen in one’s palm provides a view of elsewhere.

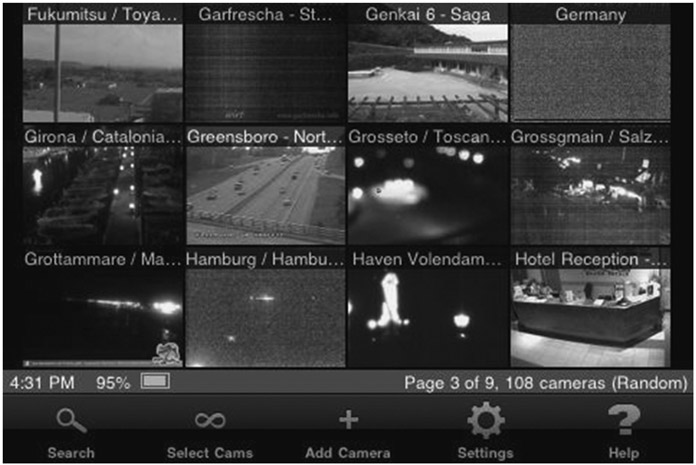

There are currently dozens of webcam applications for mobile phones. Let me give you an example of one webcam application, LiveCams.4 The opening screen of the LiveCams app presents you with an array of twelve squares, each a miniature television screen or monitor. Each square is a randomly selected live streaming image. Several more pages of live cameras follow. One can touch an image and it fills the screen. Many give the viewer the ability to pan, tilt and zoom the distant camera. One can also search for particular places and bookmark one’s favorite cams.

Unlike the more notorious of the early webcams, most of the cameras here are public cams—municipal (traffic, street scenes, beaches) or private-public spaces like skating rinks and hotel lobbies. Like early webcams, the images are blurry and indistinct, lacking detail.5 Some of the images are eerie, almost ghostly (shadowly figures glide past in a Northern European skating rink). Generically, the shadowy images remind me of evidence from crime scenes, grainy surveil-lance footage shown on the nightly news. So, like early webcams, the significance of these images is the fact that we’re seeing more than what we’re seeing. It’s about the fact that I can watch traffic in downtown Prague and not, say, the significance of particular vehicles (though this might be different if I lived in Prague and used the app to warn me about my commute). Given the quality (or lack of quality) of the image, what we see is often a product of our desire. The image is semiotically constructed by the title, place names anchoring the meaning of the image (Barthes 1977) as much as anchoring its location on the globe.

Each of the images in Figure 12.1 was in motion—the lights of cars jerkily move down a street (now here, now farther along, like flipbook images or crude animation). Some images you have to scrutinize for signs of life—or, actually, signs of liveness—in order to understand that this is, indeed, a live scene and not a screen capture. Staring at a lonely town corner, one sees a branch move slightly, or a shadowy figure step into the pool of light of a streetlamp before fading back into darkness.

Frustrated with the lack of detail, the semiotic obtuseness of the images, you tap on one and it fills the small screen. For many images, the enlargement makes a difference. For others, the blurs from ill-adjusted cameras at the limits of their resolution and bandwidth become just larger blurs. But for most, figures become more distinct, their movements fluid. The scene resolves itself into something readily identifiable. Ships move across the harbor in Japan, bikers attempt tricks in a park in Seattle, a guest confers with staff at a hotel in Russia, cars move slowly down a Swedish street. As Daniel Palmer (2000) once noted of webcams, one function is the affirmation of one’s longitude in relation to the rest of the globe. Late afternoon in Phoenix, Arizona, but night in Sweden and early morning in Japan.

Figure 12.1

Screenshot of the app LiveCams.

But then, that’s it. A few more cars, another skater gives it a go, a flag moves lazily. A key characteristic of the webcam image is precisely that very little happens. As I wrote a number of years ago, webcams in general allow for a certain scrutiny of the everyday:

[T]his scrutiny is not at the level of the close-up or enlargement (such as in film or photography), or a result of an increase in detail (because of the limitations of the medium, there is sufficient loss of detail), but a product of time. One the one hand, we have the momentary, the moment caught on camera, or a succession of such moments (a certain this-ness, this moment and then this moment) … On the other hand, we have the long stretches of time where we can watch a room or street or landscape for hours.

(Wise 2004, 426, 427)

The webcam becomes Lefebvre’s window, a perch to study the rhythms of the everyday (2004). But this, essentially, leaves us passive, waiting for something to happen. If we so wish, we step further into the panopticon’s guard tower and push the Control button (Figure 12.2). We zoom in a bit, exploring a detail. We pan to the left. More buildings? The open bay?

Unlike deskbound webcams, this mobile screen is not a medium to study the duration of everyday life (and actually makes a poor substitute for Lefebvre’s window) for two reasons. First, like other mobile devices they are consumed in distraction, and so lack the ability to endure over time. They are the snack, the respite, the amusement between other amusements, activities.6 Second, they drain battery power like nobody’s business, meaning that time is very limited on the app unless you are plugged into an outlet (which defeats the purpose of a mobile device). Note the drop in battery power between Figures 12.3, 12.4 and 12.5, indicated by the battery icon in the upper right.

Figure 12.2

Japan.

Figure 12.3

USA.

Figure 12.4

Sweden.

Figure 12.5

Russia.

In summary, the first implication of Haraway’s analysis, that we need to scrutinize the relation of self to screen, provides us with a complex set of practices and experiences. The infolding of hand and device triggers a variety of attentional states—some sub-attentional and habitual, some haptic, some fully visual, some articulating the stereo-attention of mediated elsewhere and proximate environment. These different assemblages of attention do not derive from any one technology alone (whether hardware or software) or any one particular practice; they are not reducible, in other words. Some assemblages we take up, and others sweep us up (and indeed produce us). But each assemblage produces relationships of power.

The presumption of personalized power implicit in mobile devices should not be underestimated; we can be interpellated as sovereign subjects with the world in our hands, available at the touch of a button. Through devices that connect and communicate, they also disconnect us, sort us, separate us, and control us, and we may have less agency than promised.

Camera to Object

The second implication we can draw from Haraway has to do with the materiality of the arrangement of camera to its object—which brings us to the literature of surveillance. As David Lyon (2001) maintains, surveil-lance is a relationship of power. Thus, in any analysis, we need to map the particularities of the situation: the location of the camera, the purpose of the camera, the presumed subject of the camera, and the organizational and institutional assemblage of which it is a part. For example, traffic cameras are part of municipal infrastructures for the management of traffic flow and density. It is one option among many to accomplish this task (from tracking the signals of mobile phones to rethinking the architecture of roadways and the structure of the urban). Tourist cameras are there to translate the location into a scene for the consumption of potential visitors (Chiba), though these can also double as devices to manage employees, customers, prevent theft, promote efficiency, and so on.

We need to consider the materiality of the camera (as Haraway considers the National Geographic cameras strapped or glued to the backs of marine wildlife) and the effects of its placement. Ike Kamphof (2011) discusses nature webcams where viewers can watch live streaming video of nests or watering holes in the wild. We need to consider the ways that the presence of this camera (and its attendant equipment) disturbs and alters the “natural” scene in front of us. For example, what happens if a camera in an eagle’s nest breaks down? A tension arises between the welfare of the nest and its residents and the desires of distant viewers to watch them.

The intentions of each of the examples above (Figures 12.2–12.5) are not clear, but we may speculate on their relationship to what they survey. Figure 12.2, of Chiba, is a wide shot of the waterfront from across the water. It presents the city as landscape, as a whole, rather than focusing on a detail. Perhaps this is for the tourists’ gaze. It may be sponsored by a municipality (civic promotion, harbor patrol) or private concern. But through it we grasp Chiba as an urban spectacle. The Control button on the lower right allows exploration. Figure 12.3, of the park in Seattle, is much more particular: a wide shot of a park where youth ride bikes or skateboards over and around obstacles. The shot encompasses the park in its entirety. This could be civic promotion (facilities for youth recreation in the city) or public safely (to protect the youth there, or to keep an eye on them). Notably, we are at sufficient distance that features of individuals are not distinguishable, and we are not allowed the ability to control the camera to zoom in closer on individuals (maintaining a sense of privacy and safety, especially of a vulnerable population). Figure 12.4, the street corner in Kristinehamn, is a public area of the city, but more specific than the sweep of spectacle of Chiba. We don’t grasp the city as a whole but as a more intimate approach to one block. Like Figure 12.3, we are not close enough to be part of the scene, or even to identify (with) the figures there. We look down on the scene as if from a balcony, higher, it seems, than the light poles. It is surveillance from a window. Compare this image with Figure 12.2, where we look up to the city, and 12.3, where we look slightly down but are closer to being on the same level as the bike riders. Figure 12.5, the hotel reception area in Russia, is an interior scene, angled sharply so that we gaze down at the front desk. It is the ever more familiar position of the surveillance camera, anonymous and “objective.” We watch over, but do not participate. Though the figures are identifiable, the camera does not allow us identification with any of them. This is the most voyeuristic of the cameras, and while it may be an attempt to appeal to potential customers, it exudes the scent of control.

Articulations, Infoldings and Ethics

What Haraway’s third point suggests is that the remote cam viewers are implicated in the relations of surveillance camera and spectator. I am implicated in the organizational relations that keep Russian hotel employees under careful watch, for example, or in the close observance of Seattle’s youth (to keep them out of mischief, perhaps, and to keep them from harm as well).

Kamphof argues that conservation websites leverage the phenomenological closeness (affect) of the camera image into identification with ecological causes and specific animals (usually the cute ones), which leads to donations. That is, an affective alliance is established which is then exploited for capital. Kamphof writes, “A reflex to donate in response to seeing a cute animal lacks in moral weight, even by more lenient standards” (2011, 267). In that the mobile screen is much more a part of our bodily schema than even laptop computers, the image in our hand presents an even closer intimacy, an infolding.

As David Lyon (2001) has pointed out, surveillance has two faces: care and control. Participating in this surveillance assemblage through the phone app places one within a regime of control, but not directly. You have no individual power over those surveyed (one is not a guard in the panopticon). But what is established, for oneself, is a reinforcement of the continued consciousness of surveillance in other aspects of your life, and a reinforcement of the system of cameras itself by providing to it your attention (making it a viable site for advertising, or simply through its popularity, counted in hits, encourages the site to draw on aspects of the attention economy). Following Heidegger’s notion of care as an ontological closeness, a being-with, we can see that the remote locations and their subjects as infolded with one’s phenomenological sense of presence and place.

Control is via the act of seeing, manipulating and holding in one’s grasp the scene in question. The sight of one’s fingers wrapped around the image reinforces the sense of control and domination (the world in my hand). Care is in the sense of being-with. Though the images refuse immersion, there is the being-with of the synchronic image—we move here as they are moving there (Wise 2004). Holding an image in one’s hand can be a gesture of care (you’re in good hands, as an insurance advertisement tells us). There is a certain intimacy to this gesture as well. As Ingrid Richardson writes, “Thus, there is a certain haptic intimacy that renders the iPhone an object of tactile and kinesthetic familiarity, a sensory knowingness of the fingers that correlates with what appears on the small screen” (2012, 144). In addition, features of the iPhone, like FaceTime, present real-time twoway video streaming. This is certainly a different genre of webcam—the private, interpersonal, video-phone call (like Skype)—which is neither public nor anonymous. These are filled with the eventfulness of the conversation, even if much of the conversation may be nonverbal, just the gentle gaze into another’s face (cf. Elkins 1996). In these cases, the relationship fills the screen: we no longer seek the contingent, the proof of life, the coherence of meaning. Other apps, such as Knocking, Presence or camThis! allow one to see through the camera of another iPhone. Though similar to the FaceTime feature, these apps are less about face-to-face, than allowing others to see the scene in front of one. On the one hand, this sense of shared experience falls under care, but, on the other hand, the control aspects of surveillance, and the potential for abuse, are evident (Calvert 2000).

For Haraway, the ethical obligation she refers to connects to her work with companion animals. The “ethical obligation” is to the creature on the other end. She writes: “Specifically, we have to learn who they are in all their nonunitary otherness in order to have a conversation on the basis of carefully constructed, multisensory, compounded languages. The animals make demands on the humans and their technologies to precisely the same degree that the humans make demands on the animals” (2008, 263).

But though this is an important point that could be made of any such screen and live remote image—that it puts us in relations of care with other humans and animals—I want to propose something at little broader or perhaps more radical, and that is taking seriously something that Jane Bennett says about assemblage theory. Assemblage theory emphasizes the materiality of the assemblage and what she calls thing-power, a recognition of the vitality of things. She opens her discussion with a description of some items caught in a storm drain one morning. She writes: “I was struck as well by the way the glove, rat, cap oscillated: at one moment garbage [that is, swept up in a human-centered semiotic], at the next stuff that made a claim on me” (2004, 350). The recognition of the vitalism of things, of thing-power, is that things make claims on us.7 She writes:

I want to give voice to a less specifically human kind of materiality, to make manifest what I call “thing-power.” I do so in order to explore the possibility that attentiveness to (nonhuman) things and their powers can have a laudable effect on humans. (I am not utterly uninterested in humans). In particular, might, as Thoreau suggested, sensitivity to thing-power induce a stronger ecological sense?

(Bennett 2004, 348)

To bring us to ecology, assemblage theory emphasizes the ways that “humans are always in composition with nonhumanity” (365), and the recognition of this composition creates a “sympathetic link” “which also constitutes a line of flight from the anthropocentrism of everyday experience” (366).

But perhaps, in the end, this is a lot to lay on a moment of staring at a webcam image of a Russian hotel lobby on one’s iPod while waiting for your latte at Starbucks. The challenge is to connect the webcam moment to this sprawling, heterogeneous assemblage, especially because the trajectories of much of that which composes that assemblage don’t impinge on our perceptions.

My suggestion is modest and methodological. What the assemblage version of this moment with a mobile device suggests is the starting point for a materialist mapping project. As Latour (2005) would put it: follow the actors. This is quite challenging given the mobility of the actors, the ways they keep vanishing from our conscious landscape, and their electromagnetic tethers don’t impress themselves on our perception. We should not leap too quickly to ecology, or species companionship, or common cause with humanity. If we follow the trajectories of the actors, we get not a stable structure, a synchronous snapshot of a network, but the sprawling convergence and divergence of series of events. The point is to help make visible that which is continually trying to disappear in this assemblage.8

To return to Haraway’s point about the ethical obligations of the assemblage, recognizing the kinship between people and things makes the tendency of this new assemblage to disappear ethically problematic. I realize that there is some contradiction in talking about technologies of visual attention becoming invisible, but functionally they do so. As technologies vanish from attention and fall into habit (or into the walls or beneath the surface of seemingly everyday objects) they no longer make present the materiality of technologies (their thingness), and in so doing erase the reminders that technologies carry with them of their function as well as the conditions of their manufacture and reclamation. For example, with regard to function, Adam Greenfield (2006) in his overview of ambient computing points out that when technological processes become unobtrusive we don’t consider their ramifications easily. His example is the MasterCard PayPass system, which enables one to just tap a special key fob (or mobile phone with Pay-Pass chip) rather than swiping a credit card. The ease of gesture allows one not to ponder concretely what is happening. As a result, PayPass users spend 25 percent more than regular credit card holders because the process has become unobtrusive. The same trend can be seen in the EZPass toll system (Leonhardt 2007). When one has to stop and hand over money at a toll booth there is popular resistance when tolls go up. One notices the difference. With the EZPass one never even slows down. A reader at the booth scans a chip on the windshield of the car and sends a bill later (or takes it out of your account). One never thinks about it. According to one study, within a decade an EZPass toll stop will be 30 percent more expensive than a cash toll.

The second issue with the disappearance of these devices is that what disappears as well is any sign which indicates their manufacturer, or even the fact of their manufacture (Schaefer and Durham 2007). A material thing had an existence before you bought it and put it in your pocket (or wall) and will have an existence after you throw it out. It seems as if our culture never learned the elementary psychological lesson of object permanence: out of sight does not mean that the object no longer exists. The tendency of these technologies to want to disappear distances us from the environmental devastation of copper strip mining practices, labor conditions in microchip factories, fossil fuel consumption and subsequent pollution of the distribution system, and the sheer toxicity of the machines as, once scrapped, they pile up in landfills, heavy metals seeping into water tables (see Gabrys 2011; Maxwell and Miller 2012). To talk of these technologies in terms of assemblage allows us to map these, draw the lines, incorporate radiation, repetitive strain injury and eye strain with heavy metals and other toxins, as well as privacy, control, regulation, convenience, productivity, profit, exploitation, dignity.

Along with function and material effects, a third ethical problem with their disappearance is that it allows us to ignore what Virilio (2000) called the integral accident. Every technology has inherent within it an accident particular to that technology, a disaster enfolded in its very being. For example one cannot have a plane crash without a plane, and one cannot have a plane without a (potential) plane crash. No matter how many safeguards we may establish, a nuclear accident is always somehow a part of what a nuclear power plant is. What, then, is the integral accident of the Clickable World? Data theft? Information war? Or perhaps, more likely, the disastrous inability to function that would result, should this assemblage become as much a part of our human scaffolding as it is designed to be, should it fail.

The final dimension to the ethical problem of disappearing technologies is that these are technologies—ironically—of attention (they pay attention for us), and while we forget them, they remember everything. Martin Dodge and Rob Kitchin (2007) recently brought up what they call the ethics of forgetting—that with ubicomp and new technologies and practices such as lifelogging, we need to incorporate forgetting into the assemblage.