New Imaginaries of Mobile Internet

Gerard Goggin

We are witnessing an era of intense reliance on communication and media technologies as a central feature of social life. While debate rages about the extent, nature and implications of this development, it is something that not only is observable in private and public spheres but also is a preoccupation in a range of settings. Two of the most important technologies involved in these transformations are the Internet and mobile phones. Launched in 1969, the Internet developed steadily through the 1970s and 1980s before its widespread adoption from the early 1990s onward. The mobile phone had its roots in wireless telegraphy, radio and the telephone, was made available commercially in the late 1970s, and, with the second generation standard (2G) was adopted globally also during the 1990s. Both the Internet and mobiles are now established as mature global media technologies, underpinning the disruption of other communication forms and older media. What is remarkable about these twin trajectories is that they are now entwined as “mobile Internet”—the subject of this volume. Among the highly significant implications of this melding of mobiles and Internet is that mobiles now constitute a preferred way for many people in the world—especially the poor and those on low incomes—to access Internet.

There are many questions raised by the emergence and rise of mobile Internet, which is at the center of cultural and social transformations in many countries. My focus in this chapter is on the distinctive and novel manner in which the social is being re-created (or cocreated) along with the production, consumption and shaping of these new technologies. To understand this, I am interested in considering how mobile Internet as an ensemble of technologies is imagined, and how it participates in wider social imaginaries.

Imagination is a potent, evocative concept in understanding human society and history. The recognization of imagination has often guided studies of new media (Balsamo 2011; Boddy 2004; Douglas 2004; Kirkpatrick 2013; Wheeler 2006). Imagination is closely related to the more delimited concept of “imaginary.” Used across a range of philosophical, social and cultural inquiries (Wilson and Dissanayake 1996; Le Doeuf 1989; Taylor 2004), an “imaginary” refers to a cluster of interrelated ideas. While not necessarily an “ideology” or possessing an ideological function, an “imaginary” is a pervasive, widely held attitude, perception or set of beliefs that colors the way something is regarded, understood or even shaped. Paradoxically, perhaps, in this sense an “imaginary” is not just “imaginary” (that is, conforming to the dictionary definition of only existing in the imagination). Rather, an imaginary has a material existence, as well as real influence and force.

In this chapter, I will be especially drawing upon the philosopher Charles Taylor’s concept of “social imaginary” (Taylor 2004). Taylor notes that an imaginary is a contradictory, ambiguous thing. It has a relationship to actual practices, and also new possibilities. It also is the matrix of values and norms that frame an understanding of the world. For Taylor, the “social imaginary is not a set of ideas; rather, it is what enables, through making sense of, the practices of a society” (Taylor 2004, 2). Taylor suggests that social imaginaries:

have a constitutive function, that of making possible the practices that they make sense of and thus enable … Like all forms of human imagination, the social imaginary can be full of self-serving fiction and suppression, but it also is an essential constituent of the real.

(Taylor 2004, 184)

Taylor argues that Western modernity is characterized by a “new conception of the moral order of society,” which mutates into a social imaginary spawning our characteristic social forms such as the “market economy, the public sphere, and the self-governing people, among others” (Taylor 2004, 2). One of Taylor’s key insights is the importance of social imaginaries for helping people make sense of transformations. Discussing the rise of modern individualism as “by its very essence a solvent of community,” he notes that with the French Revolution we can see people “expelled from their old forms—through war, revolution, or rapid economic change—before they can find their feet in the new structures, that is, connect some transformed practices to the new principles to form a viable social imaginary” (Taylor 2004, 18).

Taylor’s account of social imaginaries is especially suggestive for our topic of mobile Internet. In mobile phones, we have a flexible, versatile, powerful and very widely used set of technologies that are not only tools for negotiating everyday life for billions of people—they support practices and meanings about people’s lives, and where they fit into structures of power. Unsurprisingly, there is an extensive literature on the social and cultural significance of mobile phones, and what they represent. A new development in mobiles since at least 2007 onward has been the pervasive of mobile Internet technologies, which are now highly important to how “ordinary people ‘imagine’ their social surroundings,” as Taylor puts it (Taylor 2004, 23). My argument is there is a new social imaginary emerging, associated with and centring upon mobile Internet—correlated to a set of moral norms and values for society in general—a “common understanding that makes possible common practices and a widely shared sense of legitimacy” (Taylor 2004, 23). Mobile Internet suggests a new category, which subtends the constitutive tensions in late modernity that Taylor identifies in his account of modern social imaginaries. In particular, we find a tension between the notion of sharing, central to contemporary social media, and mobile Internet media, on the one hand, and the logics of economic individualism and social exclusion that underpin this period of digital technologies. Crucially mobile Internet takes shape differently in particular national and cultural contexts, and modernities—just as Taylor notes that “modern social imaginaries have been differently refracted in the divergent media of the respective national histories” (Taylor 2004, 154). Indeed the social imaginaries in which mobile Internet are implicated are especially interested because they engage a range of modernities—Western, non-Western, and others.

Mobile Internet Assemblages

In itself, mobile Internet is a complex assemblage (Bennett and Healy 2011)—a set of media and communication ecologies that has, until recently, slowly taken shape. With the popularity of the Web and its characteristics—ease of use, linking the resources of the Internet, working across devices, platforms, applications and screen—quickly established by the mid-1990s, the mobile phone was an obvious platform for the industry to concentrate its efforts (Nokia, 2000). Finnish giant Nokia, along with Motorola, Ericsson and Unwired Planet (later to become Phone.com), instigated the Wireless Application Protocol (WAP) forum in 1997 (Kumar, Parimi and Agrawal 2003; WAP Forum 2000). WAP was a key way that mobile manufacturers and carriers sought to implement an Internet-like environment on mobile phones. Rather than the mobile phone functioning like any other Internet-connected device (for instance, the way Wi-Fi operated), WAP extended a Web client to the device—a crucial difference from the Internet TCP/IP underpinning the public Internet (Huston 2001). In any case, due to slow data speeds and limitations on handsets, operating systems, and applications, WAP proved a frustrating experience for users—and only attracted limited interest (Goggin 2006; Helyar 2001).

The celebrated pioneer in mobile Internet, however, was the i-Mode “ecosystem,” developed by the Japanese carrier NTT DoCoMo (Natsuno 2003). The i-Mode system was a packet-switched data service that operated over the mobile phone network. The innovation in i-Mode lay in the creation of close relationships between networks (owned by DoCoMo) and the other crucial elements of the whole mobile data environment, such as handsets, gateways, servers (with the billing systems), portals and content. Content providers were encouraged to develop products (such as mobile music), and purchase of the service by consumers was made as easy as possible—a notable achievement in the early days of mobile Internet. It took some years before the same ease of use was available in other country—when WAP did become widely used, in its incarnation as WAP 2.0—as mobile portal and premium services took off in 2002–2005, with music, video and other downloads, and multimedia and text messaging proved mainstays of mobile services (Spurgeon and Goggin 2007). This eventual take-up of WAP, harnessed to different business models (Ramos et al. 2002), was one reason why i-Mode did not prove exportable in its original form (Maitland, Bauer and Westerveld 2002; Goggin 2006)—although the approach, applications and services which it incubated are obvious precursors to Apple’s iPhone, Google’s Android, and other smartphones and apps platforms (Goggin 2011b).

It is probably more accurate to see the history of mobile Internet as an evolutionary process, but it is certainly possible to discern two periods of intense development and activity. So far I have discussed the period of the late 1990s and early 2000s, where there was focused, coordinated activity on conceiving, designing and implementing mobile Internet. The second period dates from roughly the middle of the first decade of the 2000s, we can point to an overlapping set of developments that less than five years later made mobile Internet a very widely discussed focus for directions in digital technology—and which greatly shifted the social imaginary of mobile Internet.

To start with, networks developed greatly, with cumulative effects. From a difficult start, third generation networks (3G) were widely rolled out, supporting higher data transfer rates. Existing 2G networks were also extended to better support mobile data. Thus Internet could be much more easily accessed via mobile networks—including mobile video, games, music, photo-sharing sites and the other facets of contemporary “broadband” Internet experience (in the Global North, at least). Mobile networks were also used to provide mobile broadband for laptop computers, tablets and other devices. That is, a chip or USB modem was used in conjunction with a computing device to provide broadband Internet. Mobile broadband achieved very rapid take-up around the world. Fourth generation (4G) mobile networks—involving a mix of mobile cellular and wireless Internet (Wi-Max, and other successor technologies for Wi-Fi) technologies—promised to make much faster access Internet speeds a reality. Finally, developments in next-generation broadband networks accelerated the process of replacing traditional fixed and mobile telecommunications circuits with Internet protocol based packet-switch networks—with significant implications for mobile Internet also (Middleton and Given 2011).

Another important factor in the second phase of mobile Internet is the continued development of mobile handsets. Multimedia handsets predominated in markets where consumers could afford them. With the success of Apple’s iPhone, launched in mid-2007, and development of Google’s Android operating system, smartphones became very fashionable. Smartphones were especially predicated on mobile Internet access, allowing downloading and use of “apps.” Indeed the whole area of applications for mobiles gained dramatic impetus. As well the phenomenon of smartphones and other multimedia phones providing a much better platform for applications, the advent of Internet-based “social media” engaged mobiles in particular.

In Asian countries, mobiles have long been important in Internet access and use—especially in their pioneering of social software, with long-established communities around applications such as Cyworld (South Korea) and Mixi (Japan) (Hjorth 2009). In the West, social networking systems had been developed around desktop Internet platforms until comparatively recently (Boyd and Ellison 2007)—with exceptions such as mobile social software, experimented with from the late 1990s (Humphreys 2008). So it was not until 2007–2008 that social networking systems, software and social media become widespread on mobiles in non-Asian countries—and then the growth was phenomenal. By 2010, Facebook had established itself as the leading social networking system in the West, with a substantial proportion of users accessing it on mobiles. In the process, it also become a platform adopted, and reshaped, by users in non-Western countries—something underscored by its role in the “Arab Spring” uprisings of late 2010 and early 2011, which were claimed to be led by “Facebook revolutionaries”—the “Facebook generation” that transcended “classical” political movements (Beaumont and Sherwood 2011; Shenker 2011). The prominence of Face-book’s rise, of course, obscured the fact that there were a myriad of other social networking and social media applications used across the world, not least in markets like China (Qiu 2009; Yu 2009).

Finally, the second phase of mobile Internet was characterized by the interaction of a wide range of different networks and devices—over and above mobiles and Internet. This is evident with the rise of locative media, based on positioning, locational and mapping technology, such as Global Positioning Satellites (GPS), Google Maps and Earth (and other “geospatial Web”) (de Souza e Silva and Frith, 2012; Farman, 2012; Gordon and de Silva e Souza, 2011). Also fast emerging were networks of sensing technologies, Radio Frequency ID (the long-awaited “Internet of Things”), and other technologies. Mobile Internet, then, becomes an especially complex assemblage in its second phase, from 2005 onward (Goggin 2009). It is constituted from a series of quite contingent interactions between different kinds of networks, devices, applications and practices. Mobile television, for instance, becomes as much about the possibilities of using a mobile phone to record video and then upload it to YouTube, as it does about broadcasting television programs to a user’s mobile phone (which was the mobile industry’s early vision). Or mobile Internet is as much about someone using an app to collect the statistics on their bicycle journey to work (“map my ride”), and sharing that with others, as it is about using their phone to browse the Web.

Mobile Internet is also very much bound up, from 2012 onward, with the rise of the pervasive data creation, collection, processing and harvesting of what is commonly—and obviously problematically—referred to as “big data.” The affordances of mobile Internet for such nigh-compulsory everyday data surveillance were dramatized in 2013–2014, through the many relevations of the leaks of material made publicly available from U.S. whistle-blower Edward Snowden. Take, for instance, one exemplary allegation that the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) and its British counterpart GCHQ were developing capabilities to harvest data from “leaky” smartphone apps, such as the famous Angry Birds game:

The data pouring onto communication networks from the new generation of iPhone and Android apps ranges from phone model and screen size to personal details such as age, gender and location. Some apps, the documents state, can share users’ most sensitive information such as sexual orientation—and one app recorded in the material even sends specific sexual preferences such as whether or not the user may be a swinger … Scooping up information the apps are sending about their users allows the agencies to collect large quantities of mobile phone data from their existing mass surveillance tools—such as cable taps, or from international mobile networks—rather than solely from hacking into individual mobile handsets.

(Ball 2014)

As the work of many scholars makes clear—especially the pioneering work of Mark Andrejevic (2007, 2013)—such “sharing” of personal information is the well-entrenched dark side of the affordance of social and mobile media, a topic to which I will shortly return.

Imagining Mobile Internet

While mobile phones have been the subject of great promises and hopes for sometime—ending poverty, for instance, as Iqbal Quadir, banker and founder of Grameen Phone, famously suggested in his widely noticed 2007 TED talk (Quadir 2005; cf. Toyama 2010)—it is fair to say that the Internet has been figured as a sublime medium, since the invention of the World Wide Web and its mass diffusion from 1991 onward. This is evident in one of the most detailed studies of the development of ideas about the Internet, Patrice Flichy’s The Internet Imaginaire (Flichy 2007). Flichy sets out to chart the emergence of a set of ideas associated with, and influencing the development of the Internet—the discourses that form an “integral part of the development of a technical system” (Flichy 2007, 2). Because of the significance of the U.S. to how the Internet emerges in its early phase, he focuses upon the American context. As he notes, the imaginary he documents is quite specific to the American context—while influential elsewhere. Indeed Flichy remarks how the Internet imaginaire was “born in the particular context of the United States but subsequently became universal” (Flichy 2007, 211). In particular Flichy proposes that there is a “cyber-imaginaire,” produced from the “technological imaginaire” associated with the technical projects of conceiving and developing the Internet (Flichy 2007, 107). Key ideas in the composition of this cyber-imaginaire can be traced back an elite of thinkers on the future initially (the likes of Marshall McLuhan, George Gilder, Nicholas Negroponte and others), but once it achieves cohesion and force, it operates much more broadly as the dominant way to imagine the Internet.

If we can transpose the linguistically and culturally specific concept of the imaginaire, and Flichy’s work on the emergence of the Internet, to our contemporary terrain of the mobile Internet some two decades on, then we can find both interesting resonances and divergences. In the first phase of mobile Internet in the late 1990s to early 2000s, when the idea of such technology is not widely appreciated, we find a technological imaginary being shaped. Hence Nokia’s proposal:

We are witnessing the transformation of the mobile phone from a voice-centric communication device to a tool for managing business and private life, and for triggering and sharing experiences … In our vision, the Internet will go mobile, just as voice communication has done.

(Nokia 2000, 2)

The larger social imaginary associated with early mobile Internet is predominantly that of the information society (something explicitly noted in Nokia’s 2000 WAP White Paper). The information society looms large in the pioneering Finnish social theory of mobiles (Kopomaa 2000). The information society also proves a serviceable and durable concept for orienting the larger European intellectual and policy frameworks in which mobile Internet developments are being grasped, as part of greater ensembles of technological systems and notions of the social.

Interestingly, of course, the information society as a concept was greatly influenced by Japanese efforts to grasp and theorize the interrelationships between technology and society in the 1960s (Webster 2002). Yet when it comes to the Japanese i-Mode, we find a distinctive tone to the celebration of this pioneering technology and the culture that produced it (Barnes and Huff 2003; Funk 2001)—often partaking of what David Morley and Kevin Robins term a “techno-orientalism” (Morley and Robins 1995). Writing on the vogue for i-Mode, Mizuko Ito situates it in a deep-rooted “Euro-American fascination with Japanese technoculture,” that invokes Japan as an “alternative technologized modernity”:

On the one hand, i-mode is held up as a technological and business model to be emulated; on the other hand, discourse abounds on the cultural strangeness of Japanese technofetishism that casts it as irreducibly foreign.

(Ito 2005, 2)

It is worth bearing in mind the specific nature of these social imaginaries attendant on the first phase of mobile Internet—European and Japanese—as we now move to consider second, current stage of mobile Internet, and the social imaginaries associated with it.

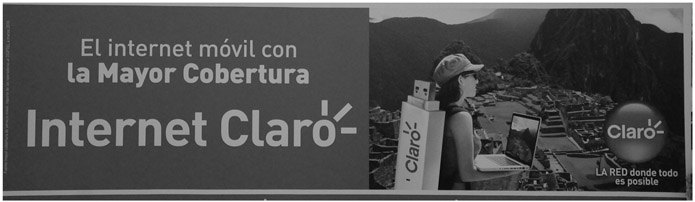

Figure 7.1 “Mobile Internet with the Best Coverage … The Internet Where All Is Possible” (Claro advertising billboard, Cusco, Peru, 2011).

Let me provide two texts that illustrate key aspects of this social imaginary of contemporary mobile Internet, both drawn from advertising in Latin America. The first text is an advertisement for mobile Internet (Figure 7.1), offered by Claro, an interest of the Mexican giant América Móvil, owned by the world’s richest man, Carlos Slim Helú (Goggin 2011a, 23). Mobile Internet, especially mobile broadband, is highly significant in Latin America, where it is the preferred type of Internet connection (Flores-Roux and Mariscal 2011, 5; Mariscal, Gamboa and Rentería Marín 2014).

The ad targets travelers to the iconic Incan city of Machu Picchu, at the time being celebrated for its one-hundredth-year anniversary of its “scientific discovery” by Hiram Bingham, the North American explorer and Yale University professor (Bingham 1948). A young woman, superimposed on one of the high views of Machu Picchu (perhaps from the Sun Gate, through which hikers on the so-called Inca Trail arrive at the site), has a double purchase on its splendors. She enjoys contemplating Machu Picchu with her own eyes, with a version of the image also displayed on the screen of her laptop. What is especially striking and amusing about this advertisement is how awkward and cumbersome the technology of mobile Internet seems here (indeed an ironic counterpoint to the subtle and powerful technologies the Incan society produced, in testaments to their culture such as Machu Picchu). The conceit of the backpacker sees the USB modem carried on her back, but expanded to the full size of a backpacker. She carries her laptop as commonly held, cradled in her arms, but, again, achieving connectivity and coverage at a fair price to traveler ease and comfort. The motto of the advertisement sings the praises of the “Internet where all is possible” (“La red donde todo es posible”), but the grounds of this utopia lie firmly in the crushing immobility of lugging around the burdensome combination still needed of laptop and mobile broadband device.

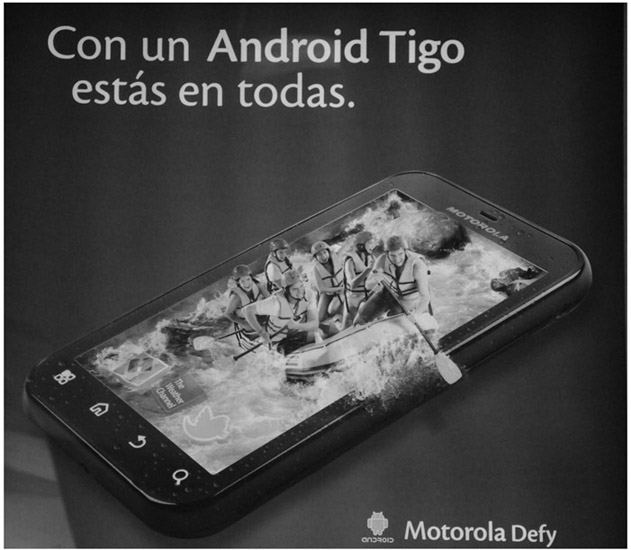

Figure 7.2 “With an Android Tigo, You’re in Everything” (Tigo advertising billboard, Cartegna, Columbia, 2011).

If the backpacker is a suitable emblem for the harnessing of mobiles and Internet, with mobile broadband, advertisements for smartphones typically offer a different take. An advertisement for a Motorola smartphone using Google’s Android operating system emphasizes that with such a device “you’re in everything” (Figure 7.2).

This text nicely underscores the claims and potential experiences of smart-phones by recoding them into categories redolent of the immersive, interactive viewing and audience modes and experience of film and television. The action adventure on the small screen literally spills over the frame of the phone, rather like the trope of the television program erupting into the viewer’s lounge room. The “Weather Channel” icon reminds us that the smartphone provides recognizable television programming and content as well as Internet and new kinds of apps. For many, the mobile phone is no longer an adjunct, but indeed an essential tool and cherished object for navigating the rapids of society.

These two advertising texts provide examples of two prominent representations of mobile Internet, with strong continuity with preceding practices and ideas of the Internet (as evident with the modem-equipped backpacker at Machu Picchu) and mobile devices (the white-water rafting of the Android). Both also suggest new possibilities for mobile Internet. The first image struggles to resolve the tensions between the unwieldiness of the technology, on the one hand, and the infinite possibilities it affords, on the other hand. The second image draws on the practices and representations of mobile phones, established now over three decades. It also draw upon the long histories of media spectatorship and engagement, and the codes and repertoires by which they have found their way into advertising, to provide a new twist—on the small screen on the smartphone. Both these texts provide us with good examples of constituent elements of the emergent social imaginary emergent associated with mobile Internet. However, there is another category that, in my mind, really animates and distinguishes this imaginary that increasingly we find as a feature of discourse on mobile Internet: the concept of sharing.

The Politics of Sharing

At the heart of this new social imaginary is sharing—and how we understand this. In relation to mobiles, we see this imaginary emerging from the late 1990s, especially in relation to practices of text messaging, music, and photo and image sharing, and being capitalized upon especially in the smartphone era. Hence the title of this essay taken from a Peruvian billboard advertising smartphones offered by the Spanish mobile giant Movistar. (Movistar is owned by the parent company Telefónica, which dominates the market in Spain and has a strong presence in over a dozen countries in Latin America [Martínez 2008]). The advertisement (Figure 7.3) depicts a young man showing a young woman something on his phone, both close together and smiling, with the tagline “shared, life is more.”

Figure 7.3

“Shared, Life is More” (Movistar advertising billboard, Lima, Peru, 2011).

The theme of sharing is something that recurs in many advertisements and other representations of mobile Internet. Interestingly, the image in Figure 7.3 is strongly grounded in mobile phone culture. While mobiles were most often thought—in Western societies especially—to be individual, personal devices, they were shared from their inception (Crawford and Goggin 2008; Weilenmann and Larsson 2001). With the advent of camera phones, especially preceding the easy sending or broadcasting of pictures taken, mobiles were often used to display and show photos to friends, intimates, colleagues or strangers. The phone itself functioned as a photo album, but also a prized repository for digital memorabilia and collectables. In the Chinese context, Leopoldina Fortunati and Shanhu Yang have described such a socio-technical ensemble, not so much as “networked individualism” (Miyata et al. 2005) but as “semi-socialized individualism” (Fortunati and Yang 2012). With the advent of Facebook, apps and other personal media technologies underpinned by much faster mobile Internet, interoperable applications (for example, photos taken on a smartphone can be easily tagged and uploaded to the Internet, with sites such as Facebook or Flickr integrated into Apple iPhone or other applications), and the interweaving of mobiles and Internet in many other ways, sharing increasingly occurs across devices and platforms, reframing the previous centrality of mobile devices to collective, reciprocal investments—and generalizing the cultures of use, and rhetorics, based on sharing.

Sharing of files and content was the defining feature of peer-to-peer (p2p) networks from the late 1990s that came to general notice with Napster (music sharing) and bittorent (Internet downloading of television and movies). Since the appearance at least of Web 2.0 as a notion (O’Reilly 2005), there has been much discussion of the important role of the user in digital technologies, and the requirement for participation in their design and operation. The idea of “user-generated content” accentuated the role that users played in creating the kind of content that became widespread and attractive in digital participatory culture—for example, creating videos for YouTube (Burgess and Green 2009), or play an important role in cocreating online games. Discussions of social media also note the importance of users contributing information and content, and engaging in interaction, as what animates applications such as social networking systems, blogs, or micro-blogging software such as Twitter. In a corrective to the postulate of the user as ceaselessly productive, some scholars have also noted the importance of the bulk of other users who make sense of such user-productions by their lurking, listening and consumption. However, there is a deeper, much more fundamental logic at stake here. This has become evident in the concerns felt by many about the compulsory nature of many social media platforms that compel users to provide their information.

Facebook is perhaps the most prominent example (not least because it is a repeat offender), raising many issues of privacy and control of users’ information. More recently, the rising popularity of locative mobile media has heightened such anxieties. Smartphones, especially, have the capacity to gather detailed information about a user’s whereabouts and location, tracking their journeys through space and time (Wilken and Goggin 2014). In addition, apps such as Foursquare are available that present users with the dilemma about where, to whom and why to allow information about their location to be relayed to other users (de Souza e Silva and Frith 2012). Critically, these developments in mobile Internet center on sharing.

As I have mentioned, sharing has been a prominent theme in Internet culture, stretching back past p2p networks to newsgroups, and much earlier sociotechnical developments in the Internet. At a certain point in the development of the Internet, such sharing was theorized in very interesting ways via the notions of the gift (see, for instance, Barbrook 2005; Veale 2003). Yet sharing takes on new dimensions with mobile Internet. The socius of mobile Internet valorizes sharing—as represented in the Movistar advertisement above. Yet forced sharing of information is, at another level, a condition of entry into mobile Internet, and a requirement of participation (Meikle 2014). So there is evidently a tangled mix of practices, ideologies, desires and materialities fused in this emergent social imaginary of mobile Internet, to be confronted and disentangled.

Conclusion

It is not possible to offer a full inventory of sharing practices as they figure in mobile Internet. As my brief discussion here entails only some of the most obvious examples that have figured prominently in North America and Europe—especially the former when it comes to locative media. There is some research on sharing practices with mobile phones in a range of other locations and cultures, but as yet little work on mobile Internet. Yet we are aware that there is a very wide diversity of practices developing, specific to particular regions and setting (not least Latin America, with its reliance on mobile broadband).

It is still arguable where sharing is the conceptual wellspring feeding into new social imaginaries in which mobile Internet figure—as this may not be the case across specific locations. That said, sharing certainly features in discourses across different parts of the world, and appears to be at the heart, mutatis mutandis, of new media forms. Of course, sharing has long been believed to be at the heart of human society, bound up with reciprocity, the gift, and communication (Mauss 1966; Strathern 1998). So in mobile Internet we may see an ancient fundamental being invoked in new ways, offering a new solution to the modern problem of how to reconcile individualism, the corrosiveness of the new economy, and what creates the public and private spheres, and community.

This is worth bearing in mind as we survey the global scene in which mobile Internet is profoundly implicated in the epochal social transformations of our time—the rise of China, and its urbanization; the “Latin American” century; the realignments in Europe; the new prospects of Africa; democratic uprisings in the Middle East; the global finance crisis and the dissent it has provoken. Here we have a protean technology, playing a concrete, yet highly resonant symbolic role in the remakings of these societies. We might recall Taylor’s remark that “modernity is also the rise of new principles of sociality,” and in the centrality of sharing in mobile Internet, and broader convergent digital media, we may yet find something that genuinely productive, that exceeds the harvesting of consumer and users in these new systems of extracting and exploiting value.

Sources

Andrejevic, M. iSpy: Surveillance and Power in the Interactive Era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007.

Andrejevic, M. Infoglut: How Too Much Information Is Changing the Way We Think and Know. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Ball, J. “Angry Birds and ‘Leaky’ Phone Apps Targeted by NSA and GCHQ for User Data.” Guardian. January 28, 2014. Accessed February 14, 2014. www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jan/27/nsa-gchq-smartphone-app-angry-birds-personal-data

Balsamo, A. Designing Culture: The Technological Imagination at Work. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011.

Barbrook, R. “The Hi-Tech Gift Economy.” First Monday. no. 3 (2005). Accessed March 30, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v3i12.631 (update of article first published in 1998)

Barnes, S., and S. Huff. “Rising Sun: iMode and the Wireless Internet.” Communications of the ACM. no. 46 (2003): 79–84.

Beaumont, P., and H. Sherwood. “Egypt Protesters Defy Tanks and Teargas to Make the Streets Their Own.” Guardian. 28 November, 2011. Accessed March 21, 2014. www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/jan/28/egypt-protests-latest-cairo-curfew?INTCMP=SRCH

Bennett, T., and C. Healy (eds.). Assembling Culture. London: Routledge, 2011.

Bingham, H. Lost City of the Incas: The Story of Machu Picchu and its Builders. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1948.

Boddy, W. New Media and Popular Imagination: Launching Radio, Television, and Digital Media in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Boyd, D., and N. Ellison. “Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. no. 13 (2007). Accessed March 21, 2014. http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol13/issue1/boyd.ellison.html

Burgess, J., and J. Green. YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture. Cambridge, UK, and Malden, MA: Polity, 2009.

Crawford, K., and G. Goggin. “Handsome Devils: Mobile Imaginings of Youth Culture.” Global Media Journal. no. 1 (2008). Accessed March 21, 2014. www.hca.uws.edu.au/gmjau/archive/iss1_2008/crawford_goggin.html#_edn1

de Souza e Silva, A., and J. Frith. Mobile Interfaces in Public Spaces: Locational Privacy, Control, and Urban Sociability. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Douglas, S. J. Listening In: Radio and American Imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

Farman, J. Mobile Interface Theory: Embodied Space and Locative Media. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Flichy, P. The Internet Imaginaire. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.

Flores-Roux, E., and J. Mariscal. “Oportunidades y Desafíos de la Ancha Móvil [Opportunities and Challenges of Mobile Broadband],” Actos de la V Confer-encia ACORN-REDECOM, Lima, 19–20 May, 2011. Retrieved November 24, 2011. www.acorn-redecom.org/papers/2011Flores-Roux_Espanol.pdf

Fortunati, L., and S. Yang. “The Identity and Sociability of the Mobile Phone in China.” In Mobile Communication and Greater China, edited by R. Wai-chi Chu, L. Fortunati, P.-L. Law and S. Yang, 143–157. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Funk, J. L. The Mobile Internet: How Japan Dialed Up and the West Disconnected. Pembroke, Bermuda: ISI Publications, 2001.

Goggin, G. Cell Phone Culture: Mobile Technology in Everyday Life. London and New York: Routledge, 2006

Goggin, G. “Assembling Media Culture: The Case of Mobiles.” Journal of Cultural Economy. no. 2 (2009): 151–167.

Goggin, G. Global Mobile Media. London and New York: Routledge, 2011a.

Goggin, G. “Ubiquitous Apps: Politics of Openness in Global Mobile Cultures.” Digital Creativity. no. 22 (2011b): 147–157.

Gordon, E., and A. de Silva e Souza. Net Locality: Why Location Matters in a Networked World. New York: Wiley, 2011.

Helyar, V. “Usability of Portable Devices: The Case of WAP.” In Wireless World: Social and Interactional Aspects of the Mobile Age, edited by B. Brown and N. Green, 195–206. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001.

Hjorth, L. Mobile Media in the Asia Pacific: Gender and the Art of Being Mobile. London and New York: Routledge, 2009.

Humphreys, L. “Mobile Devices and Social Networking.” In After the Mobile Phone? Social Changes and the Development of Mobile Communication, edited by M. Hartmann, P. Rössler and J. Höflich, 115–130. Berlin: Frank & Timme, 2008.

Huston, G. “TCP in a Wireless World.” Internet Computing, IEEE. no. 5 (2001): 82–84.

Ito, M. “Introduction: Personal, Portable, Pedestrian.” In Personable, Portable, Pedestrian: Mobile Phones in Japanese Life, edited by M. Ito, D. Okabe and M. Matsuda, 1–17. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005.

Kirkpatrick, G. Computer Games and the Social Imaginary. Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2013.

Kopomaa, T. The City in Your Pocket: Birth of the Mobile Information Society. Helsinki: Gaudeamus, 2000.

Kumar, V., S. Parimi and D. P. Agrawal. “WAP: Present and Future.” Pervasive Computing. no. 1 (2003): 79–83.

Le Doeuff, M. L’Étude et le rouet. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1989.

Maitland, C. F., J. M. Bauer and R. Westerveld. “The European Market for Mobile Data: Evolving Value Chains and Industry Structures.” Telecommunications Policy. no. 26 (2002): 485–504.

Mariscal, J., Gamboa, L. and Rentería Marín. “The Democratization of Internet Access through Mobile Adoption in Latin America.” In Routledge Companion to Mobile Media, edited by G. Goggin and L. Hjorth, 105–113. New York: Rout-ledge, 2014.

Martínez, G. Latin American Telecommunications: Telefónica’s Conquest. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2008.

Mauss, M. The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies, reprint ed, translated by I. Cunnison. London: Cohen & West, 1966.

Meikle, G. Social Media and Sharing. Professorial Inaugural Lecture. February, 26, 2014. CAMRI, University of Westminister.

Middleton, C., and J. Given. “The Next Broadband Challenge: Wireless.” Journal of Information Policy. no. 1 (2011): 36–56.

Miyata, K., B. Wellman and J. Boase. “The Wired—and Wireless—Japanese: Web-phones, PCs and Social Networks.” In Mobile Communications: Re-Negotiation of the Social Sphere, edited by R. Ling and P. Pedersen, 427–449. London: Springer, 2005.

Morley, D., and K. Robins. Spaces of Identity: Global Media, Electronic Landscapes, and Cultural Boundaries. London and New York: Routledge, 1995.

Natsuno, T. The i-mode Wireless Ecosystem. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2003.

Nokia. WAP White Paper. Helsinki: Nokia, 2000.

O’Reilly, T. What Is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software. 2005. Accessed November 24, 2011. www.oreilly.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/news/2005/09/30/what-is-web-20.html

Qiu, J. L. Working-Class Network Society: Communication Technology and the Information Have-Less in Urban China. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009.

Quadir, I. “The Power of the Mobile Phone to End Poverty.” TED Talk. July 2005. Accessed March 6, 2014. www.ted.com/talks/iqbal_quadir_says_mobiles_fight_poverty

Ramos, S., C. Feijoo, J. Perez, L. Castejon and I. Segura. “Mobile Internet Evolution Models: Implications on European Mobile Operators.” Journal of the Communications Network. no. 1 (2002): 171–176.

Shenker, J. “Egyptian Protesters Are Not Just Facebook Revolutionaries.” Guardian. January 28, 2011. Accessed November 24, 2011. www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/jan/28/egyptian-protesters-facebook-revolutionaries

Spurgeon, C., and G. Goggin. “Mobiles into Media: Premium Rate SMS and the Adaptation of Television to Interactive Communication Cultures.” Continuum. no. 21 (2007): 317–329.

Strathern, M. The Gender of the Gift: Problems with Women and Problems with Society in Melanesia. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Taylor, C. Modern Social Imaginaries. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

Toyama, K. “Can Technology End Poverty?” Boston Review. Nov/Dec 2010. Accessed March 6, 2014. http://new.bostonreview.net/BR35.6/toyama.php

Veale, K. “Internet Gift Economies: Voluntary Payment Schemes as Tangible Reciprocity.” First Monday. no. 12 (2003). Accessed March 30, 2014. http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1101

WAP Forum. WAP White Paper: Wireless Internet Today. Mountain View, CA: WAP Forum, 2000.

Webster, F. “The Information Society Revisited.” In Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Social Consequences of ICTs, edited by L. Lievrouw and S. Livingstone, 22–33. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2002.

Weilenmann, A., and C. Larsson. “Local Use and Sharing of Mobile Phones.” In Wireless World: Social and Interactional Aspects of the Mobile Age, edited by B. Brown and N. Green, 92–107. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001.

Wheeler, D. The Internet in the Middle East: Global Expectations and Local Imaginations in Kuwait. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2006.

Wilken, R., and G. Goggin (eds.). Locative Media. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Wilson, R. and W. Dissanayake (eds). Global̸̸Local: Cultural Production and the Transnational Imaginary. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996.

Yu, H. Media and Cultural Transformation in China. London and New York: Routledge, 2009.