Rich Ling

Some technologies become so woven into our daily experience that they are taken for granted. In many countries, the mobile phone is beginning to have this status. In 2000, about one person in ten had a mobile phone, but by 2014 there were almost as many mobile phone subscriptions as there were people in the world. Because of dual subscription phones and other doubling up of subscriptions this translated into about 50 percent of the world’s population being active users.1 About a third of the world’s population has access to the Internet, but three of four people who have Internet access can access it via a mobile phone.

The technology has established itself in a niche in our daily lives. It makes coordination of daily affairs more convenient, it allows us to stay in touch with others, and we find a sense of safety and security in having a mobile phone. Still, ownership and use of a mobile phone is not like most other forms of personal consumption because wireless phones are generally part of a socially and materially networked system. The history of the fax machine is instructive here. The fax machine started out as being a link between two specific individuals, but as it reached a critical mass, users in some social communities started to assume that everyone was available for faxing.

Having a phone facilitates many kinds of interpersonal interactions. It allows us to coordinate mundane affairs (“Hi, the bus will be at the station in about twenty minutes, can you pick me up”) and it allows us to work out the small interactions of daily life (“I am a few minutes late because of traffic; I will get there as soon as I can. Thanks for telling me that you moved into meeting room three”). This nuanced micro-coordination is probably one of the most profound functions of the mobile phone (Ling 2012). It allows efficiency in planning and executing our interactions that was not possible with traditional landline telephony. In addition to being useful for instrumental interaction, it also enriches and intensifies social interaction. We can announce the small victories and setbacks to our social circle almost as they are happening.

Critical mass is not a specific number or a physical “fleet” of devices; it is a collective sense that a technology or a system is ubiquitous. Once this attitude has become generally accepted in a group, if our intended interlocutors, for whatever reason, do not have a mobile phone, it becomes a problem. That is, we have evolved a type of planning and interaction that assumes perpetual access to one another. The functionality of the mobile phone, in both the form of voice interaction but also to a surprising degree via texting—first in the form of Short Message System messages (SMS) and now increasingly in the form of apps such as Viber, Whatsapp (bought by Facebook in early 2014), iMessage, etc.,—is being woven into our daily interactions. To be sure, there are alternative ways of conducting coordination and social interaction, yet there is an increasing reliance on mobile mediated coordination. To the degree that it becomes “the” accepted form of interaction, it replaces other systems.

As this develops, the mediation form attains a set of courtesies and manners. We begin to understand the form of an appropriate and an inappropriate text message. We gain a sense of how long it can go before we answer an SMS from an acquaintance, a friend and a spouse. We have a sense that it is appropriate to be available and we scorn others who are less responsible. That is, we develop an ideology that supports the use of mobile telephony.

The sum of this diffusion, entrenchment and sense of correctness is a logic of reflexive expectations. We begin to assume that others will expect a certain type of use from us, and we expect the same from them. There is clearly slack in the particular forms and uses, but so long as we are within certain boundaries, we do not strain the boundaries of other’s expectations.

It is important to remember that “taken for grantedness” is not necessarily a social universal. Obviously, before a technology can be seen as taken for granted, it has to become diffused into society. That is, it has to be used (not just purchased or obtained) by enough people in the group so that it is seen as a normal part of daily interaction. It is worth noting technologies can become taken for granted within smaller subgroups. It might be that a particular clique adopts Foursquare or perhaps MXit (Walton and Donner 2011) as their method of interacting with one another. It may well be that in some groups; members absolutely have to be available via Facebook, where in others it is MySpace, World of Warcraft, via the mobile phone, or via the landline telephone. This can vary from group to group. It can also vary from culture to culture. The point is that the item needs to be, to some degree, diffused within that particular group before it can gain the status of being taken for granted. If it is only our nearest ten friends who use a particular form of mediation, we cannot extend that expectation to people who are outside of that sphere. In this way, those systems that extend across many groups (for example texting) have the advantage of facilitating interaction with both the immediate social sphere and with others who are more irregular members of the social circle.

It is interesting to consider the degree to which the mobile phone has become taken for granted; the degree to which it is engrained into our mutual expectations; the degree to which it has established its own rationality. But it is not the only technology that performs this way. There are other socio-technological systems that function in this way. Communication technologies have a particular potential to become taken for granted. If they can garner use among enough people, they generate network externalities. This is the so-called Metcalfe Law (Metcalfe 1995). Basically, as a communication technology garners users, the total value of the medium increases as each additional user joins. Metcalfe postulated that there was an exponential increase, but this is being overly optimistic. The point remains, however, that as the technology diffuses in to society, the decision to use it is not so much an individual as a social decision.

Elements of Becoming a Taken-for-Granted Technology

There are several dimensions that determine whether a technology has become taken for granted. The acid test is whether we expect it of one another. If we feel that a technology or a system is expected of us and that we expect it of others in order to be counted as a competent member of a group or a society, then it has perhaps passed the acid test. If it is a problem for others when someone does use a technology or integrate themselves into a system, then the technology has gained a certain imperative.

Elements that constitute these reflexive expectations include (1) the diffusion of the technology or system; (2) our acceptance or legitimation of the technology; (3) perhaps most importantly, the degree to which we expect that others also use the technology and they expect it of us; and finally (4) the degree to which a particular approach or solution becomes dominant and indeed changes the social ecology.

Diffusion and the Perception of Critical Mass

It is clear that in order for mobile telephony, or any other technical system, to be considered as taken for granted there needs to be certain dissemination in a group or society. There are several approaches to understanding how a technology diffuses into society. Rogers’s model of diffusion (1995) is one of these. It traces how different types of consumers adopt an item. There are the innovators who eagerly cast themselves over the new item, the somewhat less enthusiastic early adopters and so on. Eventually we come to the rather dull late adopters who seemingly only adopt an item after they are forced to at the point of social exclusion. Rogers’s adoption curve is a slightly modified Gauss curve with the boundaries between groups generally marked by standard deviations. If we set aside this rather mechanical use of statistics for a moment, Rogers’s point is that there are people who will adopt anything and who serve as a type of vanguard to try out the different items that are pushed out by the production system. The response of the first group is then filtered by what Rogers calls early adopters, who have perhaps a somewhat more sober stance. Adoption among the following groups follows a similar path, namely that their consider the experience of the previous groups before acceptance.

Rogers can be criticized for only looking at the actual purchase of an item. There is the feedback of the previous consumers when subsequent consumers make their purchase decision. However, there is an overall focus on commercial consumption. Indeed, part of Rogers’s success is that he appeals to marketing managers in industry.

An alternative approach is that of domestication (Haddon 2003; Silver-stone and Haddon 1996; Silverstone and Hirsch 1992). Consumption in the context of domestication is not simply a purchase decision. Rather it is the process through which an individual discovers an item, begins to think about how it might fit into his or her life, makes the decision to purchase or obtain the item, and then goes through the actual process of working the item into his or her daily routines. There is also a final stage in the domestication approach in that the individual is judged by others vis-à-vis the things that the individual consumes. Thus, the domestication approach does not enter into the examination of who is likely to be the first or the last to buy an item as with the work of Rogers. However, it considers consumption in a broader, and in a particularly noncommercial, way.

The final stage of the domestication approach opens an interesting notion. It suggests that after we have decided to bring an item (a particular type of watch, an iPhone or a certain type of sweater) into our lives and after we begin to use it, others are free to judge our sense of taste or adventurousness. Domestication does not, however, take the step of seeing the technology as becoming taken for granted. It considers some social dynamics. However, it does not look at the broader diffusion of the item, they way that mass adoption changes the social ecology, the development of legitimations or the idea of reflexive expectations.

An important issue in diffusion of mediation technology is that there must be the perception of a critical mass (Ling and Canright 2013). We need to think that there are enough others who are also consumers so that the device will be useful. Starting at the most basic level, it is absurd to be the only person in a country with a fax or a telephone. There would be no one else with whom we could correspond or talk. Beyond this, there needs to be a certain number of persons available in order for the device to have any utility. As diffusion becomes more general, the last holdouts may even be subject to the urgings of established users.

The establishment of these user networks is one of the decisive issues for communication technologies. Early landline telephone users often bought two telephones, i.e., one for the house and one for the office, or perhaps one for the sales office and one for the factory. The same pattern was seen among early fax users. As additional people bought landline phones or fax machines there was not, at the start, much utility to the dyad of users. These lonely users were entrenched in their own use pattern and perhaps unaware that others were also fax users. They were perhaps satisfied with the ability to fax orders and reports from office to factory. Indeed there were not many users. Quite often, at this point the devices do not enjoy scales of production and they are absurdly expensive. For example, Economides and Himmelberg (1995) report that fax machines cost as much as $2,000 in the mid 1980s when they first began to be popular. Eventually, however, users also began to understand that there were other independent dyads that had the same functionality. Thus, rather than only using their “paired” devices, they discovered that it was also possible to fax to other locations. At first this was a (well-heeled) elite, and perhaps a guarded province. However, as often happens with consumer electronics, the price of the devices fell. By the early 1990s the price had fallen to a tenth of the earlier price. Many people started using the system and at some point, it became an expectation. As additional people adopted the technology, it increased the utility of the device for existing users.2 Indeed this is the important point. When a form of mediation becomes common enough that we can expect it of one another, it has reached a critical mass. I will pick up on this thread in the section below.

The diffusion of mobile phones has a somewhat different trajectory. In the developed world, the mobile phone benefited from being a new dimension to the preexisting landline system. It often gained its first foothold in a country as a device to be used by traveling salespeople (Johannesen 1981) who were not often at a fixed location. It allowed them to coordinate their work and to be in touch with clients and their superiors (Ling 2012). From this beginning it spread to other groups, notably teens and somewhat later to the populations of developing countries (Ling and Donner 2009).

There are dynamics associated with the evolution of technologies that have a critical mass. There are difficulties associated with start-up, i.e., it is difficult to establish the original pool of users. Interactive media have an advantage in that they can often play on the dynamics of social networks in the start-up phase. However, once a system has established itself, it is less vulnerable to being supplanted by alternatives since that would involve altering the practice of the entire social network. The failed substitution of Google Wave for email illustrated this. Email, for all its limitations, is a well established and mutually recognized form of interaction. If one individual or even a small group of pioneers tries to make the transition to a substitute, they will not necessarily be able to count on all their interlocutors following suit. Thus, once a critical mass is established, there is also certain stability in the practice.

There are alternatives that do supplant previous systems. The transition from postal mail to the fax and eventually the transition to scanned documents as attachments to email illustrate this. In order for there to be a transition, however, users have to either convince or be willing to be convinced by their interlocutors of the advantages of the new system. There needs to be some compassionate reason for the first people to make the transition and they need to be willing to work through the frustrations of configuring poorly worked-out technologies. As time goes on, as the system becomes better calibrated, and as there are fewer and fewer who do not use the technology, the final holdouts face increasing insistence that they make the transition.

Legitimation

The previous discussion sounds rather brutal. As a mediation technology gains critical mass, it becomes a juggernaut that rampages through society and forces people to adopt. It is important to note that we develop legitimations and justifications to buffer the adoption process. These justifications help us to explain our use of the device or service and they help us to fit it into the broader values of the society (Berger and Luckmann 1967). They can provide the individual with all the good reasons why they should adopt. In the case of the fax machine it was the speed with which important documents could be sent. In the case of the mobile phone, people often speak of the safety and the ability to reach people regardless of where they may be. Legitimation systems can also be a bulwark against adoption. We can see in the case of mobile telephony that although there are many justifications against adoption (Ling 2004), there are seemingly more that support adoption.

When a new technology appears it is often seen as inconsequential or perhaps the hobby of those who are particularly inclined. As it becomes more engrained in society and as we need to decide whether or not we will make the transition from being a nonuser to being a user, we muster all the reasons for or against the decision. We might be fearful of the complexity and we might think ourselves as being comfortable with the existing system. On the other hand, we might be beguiled by the possibilities with the alternative or we might want to show others that we are abreast of new ideas.

As technologies diffuse, these lines of argument are built up by some to defend the existing system and by others to advocate its replacement. It is in these interactions that we develop the legitimation vocabulary for our perspectives.

Reflexive Expectations

An important point in the cycle of systemic adoption is when we take it for granted that that others in a particular group are users; when we are more surprised by finding people who are not users than we are surprised by finding those who are. In other words, the use of the technology has become routine. It is what we expect. Upon reaching criticality, use of mediation technology becomes a type of public good that is independent of individuals. Universal access (within the context of whatever universe that is being considered) is a type of commons from which all can benefit. Interactive communication services embody reciprocal interdependence. The ability to quickly get information from another person, or to provide it upon their request, is a latent potential in the system (Markus 1987).

As with any other public good there are common benefits, and there are individual responsibilities. In the case of mobile telephony, the advantage to the individual is that they can send and receive texts that help to guide them to meetings and inform them as to the status of different friends. However, the individual also has to maintain the terminal. They have to pay for the subscription and make sure that the terminal is charged, etc.

Change the Social Ecology

An important element that characterizes taken-for-granted technologies is that as they become entrenched, they make alternatives obsolete. As this happens, there is an increasing dependence on the particular item. To use the metaphor from biology, they extend the niche of the item beyond its original boundaries and, in some ways, reform the surroundings.3

To use the example of the fax machine, it changed the way that we think about the transmission of written material and indeed it changed the structure of the institutions associated with information transfer. Previous to the popularity of the fax machine, paper-based information needed to be sent physically. A newspaper clipping, a production report, a contract, etc. all needed to be mailed in their physical form. As the name implies, the fax allowed a facsimile of a document to be sent from one point to another. This functionality was a threat to the postal system. According to Skelton et al. (1995), the substitution of faxing for the postal service came to the UK in 1987 when there was a postal strike. The fax machine had been gaining ground at this time. However, the postal strike meant that users had an additional motivation to make the transition. For what was by then a relatively small investment, they could avoid the inconvenience of the striking postal workers. Looking at this situation somewhat more broadly, the fax machine moved into the niche that had been occupied by another actor. The combination of increasingly functional technology and the perhaps not unrelated strike, fax machines gained a foothold. After they had gained this position, it was difficult for the traditional postal system to regain its position. It is clear that the same technological jujitsu happened to the fax machine with the introduction of email and scanners.

Focusing again on the mobile phone, there are some of the same dynamics, albeit in a somewhat different costume. The mobile phone arose from the melding of the switched landline system with the broadcast radio system (Agar 2003). In effect, it gave us a private telephone “line” that employed the radio spectrum. While there is an existing landline telephony system, the fact that we are individually available (Ling and Donner 2009) on a continual basis is seen as a major advantage. It allowed us to send and receive texts and to chat regardless of location. Although it diffused as an extension of the landline system, it has expanded its position so as to replace the both home phones and phone booths. Indeed in many homes people are canceling or never subscribing to the landline telephone system (Dutwin, Keeter and Kennedy 2010). In other words, the mobile phone is changing the social ecology of mediated communication. In addition, it provides for texting (something that the landline system has not done in any large degree) and it has started to provide access to the Internet through advanced handsets. It is expanding the areas in which we can make and receive calls. At the same time the system of fixed terminals is being disassembled. The mobile phone is becoming structured into our communication praxis. To use a biological metaphor, the mobile phone has out-competed the landline telephone system and, after establishing itself in that niche, it has expanded the reach of what we can expect from telephony.

Texting as a Taken-for-Granted Technology

Texting is, for many, a taken-for-granted system of mediation. It has a long since exceeded a critical mass in many groups (Ling, Bertel and Sundsøy 2012), it has become legitimated in terms of the style of use and the meaning of SMS argot (Baron 2008), we often assume that others are available via texting, they assume the same of us (Ling 2012), and it has rearranged the social ecology of communication (Licoppe 2004).

Texting (either using traditional SMS or another service such as Whatsapp, Viber, etc.) is a dominant part of mobile communication. A 2009 analysis of 18,500 anonymous users of all ages in the Telenor net in Norway shows that SMS is one of the dominant activities. When counted as individual events, SMS made up more than half of what people do on their mobile phones. At that point, Individual calls make up 41 percent of the activity for normal users and data transmission (clicking on links) makes up about 8 percent of all activity. Looking at activity in the U.S., according the Pew Internet and American life project, 65 percent of 18–29-year-olds sent SMS in 2009. In 2013 it was up to 97 percent. Between 2009 and 2011 the median number of texts/day for teens 12–17 went from fifty in 2009 to sixty (Lenhart 2012). When comparing to other mediation forms, in 2013 26 percent of this age group had ever used Snapchat and 43 percent had used Instagram (Dugan 2013).

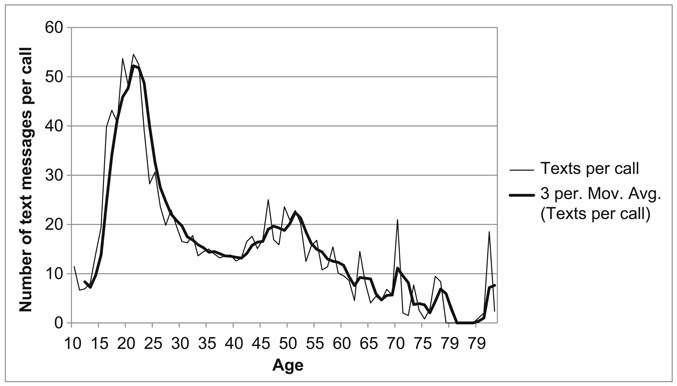

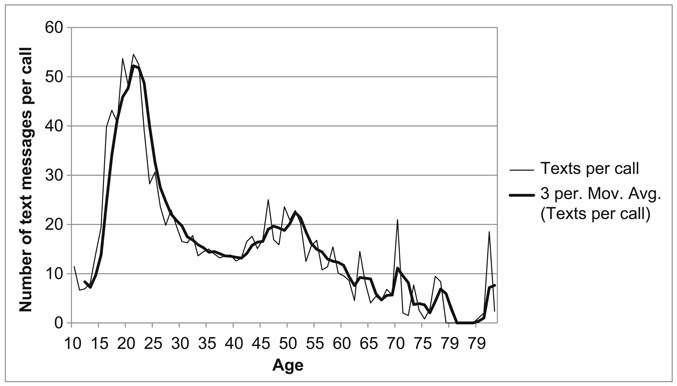

By these measures, SMS (and increasingly text messages sent through other mediation systems such as Facebook) is a central form of communication that we use in order to maintain our social ties. This functionality is likely to also be seen in various other forms of mobile texting services. Texting has moved from being a marginal form of mediation fifteen years ago to being one of the most central forms of mediated interaction. Indeed, in 2013 there were approximately ten trillion SMSs sent and received.4 This breaks down to about eight texts per day, for all 3.4 billion mobile phone users in the world. Clearly there are differences with regards our use of SMS (Lenhart et al. 2010; Ling et al. 2012). Figure 9.1 shows the relationship of

texts to calls for a sample of Norwegians in 2009. Over all, the people in the sample (that included almost 14 000 persons) send almost 4.5 texts for ever call they made. It is, however the teens and young adults who are the most SMS-oriented in their communication patterns.

Figure 9.1

Ratio of texts to calls (three-period moving average superimposed on raw data) based on 13,931 users in the Telenor net in Norway in 2009.

Texting has changed the way that we contact one another and it has changed the landscape of interpersonal interaction (Licoppe 2004). It has opened the doors for asynchronous, text-based interaction. Previous to SMS, we either had to call one another (often at landline telephones), leave notes or simply wait until we saw one another in order to exchange comments. SMS has opened a channel between individuals that did not exist before. The volume of use shows that we have taken it into our daily routines. Indeed, we arrange many facets of our lives using this form of mediation and following the broad theme of this paper, we expect it of one another. To use the formulation of James Katz, we are a problem for others when we do not use it (Ling 2012).

Taken-for-Grantedness and Social Constructionism

Suggesting that mobile telephony becomes taken for granted echoes the sociological tradition that sees social phenomena as having a type of palpable objectivity (Gilbert 1989). This perspective is somewhat different than the idea of social constructivism where it is social forces that shape technologies (Campbell and Russo 2003; MacKenzie and Wajcman 1985). On the one hand, there is the suggestion that it is the technologies that shape social practice (Schroeder 2007). There are elements of this direction that one can read into the approach taken here, namely that technological systems have a type of proscriptive tangibility. The use of the mobile phone and SMS becomes a light version of Durkheimian social facts (Durkheim 1938). That is, our collective notions of use are a social force that is difficult to avoid. They “are imbued with a compelling and coercive power by virtue of which, whether he wishes it or not, they impose themselves” (Durkheim 1938, 51).

We carry with us the sense that we are being negligent toward our social sphere when we forget our mobile phones or when we do not answer texts. We have somehow not paid due respect to our social responsibilities. There is, at some level, the sense that society is being formed as a result of the technical systems that operate in its midst. We are at the mercy of a technology and other’s expectations of how we should use it. By contrast, the social constructionist perspective is interested in examining how social processes shape artifacts. It is the values of social interaction that are brought together in the forming and refining of technology. In the one case it is the technologies (or our reading of the technologies and their uses) that are setting the tempo, and in the other case it is the social processes.

It is clear that both social constructionism and technical determinism can each be used as a lens with which to help us understand the role of new technology. We do indeed appropriate and adapt technologies to our own needs and in this way we are active “cocreators” of technology. It is also true that technologies can, as Weber suggests, stiffen into what he called the iron cage (1930, 181) such that they restructure social interactions. Neither of these positions is to be denied. However, to look at the situation from a static perspective is not particularly helpful, nor is it useful to reduce the discussion to only issue of primacy.

The approach taken here encompasses both the malleability of social constructionism and the proscriptive tangibility of the more technical deterministic approaches. It proposes, however, that this is evolutionary. It is not correct to only look at one point in time but rather it is a dynamic social process. At the point of departure, many (though not all) technologies are socially pliable. This development has been seen in the rise of texting. The Internet or the PC and their many applications are also examples of this and indeed the structure of these applications means that they are perhaps irresolvably changeable. However, with time our collective acceptance of a particular technology constrains their malleability. This can, for example, be seen in the way that time and specifically the notion of “clock time” changed during its adolescence in early modern Europe. There were many different physical devices, many different ways of counting time, different notions of when a new day began, etc. Indeed medieval Europeans had hours that varied according to the seasons and there was no general sense of when one day ended and another began. Thus, the social constructionist perspective can delight in how different cultures and different societies developed timekeeping in unique ways (indeed there is still some of this as in Levine’s Geography of Time [1998]). However, there is also a very real sense that mechanical timekeeping has become taken for granted (Zerubavel 1985). That is, it has become less malleable and we expect of one another that we both use the same timekeeping system. We have developed a more crystallized “taken for granted” relationship to timekeeping and as this has developed, it is less compliant to social shaping. There can be different advances in the devices that are used, but the system of two twelve-hour periods during the day starting at midnight is fixed. This is remarkably resistant to change.

This process of transition from malleability to crystallization is described by Berger and Luckmann in their discussion of institutionalization of social practice (1967). They describe how social artifacts (mobile phone use for example) form as a result of social interaction. We create notions of one another’s actions that eventually become engrained in what they famously call the “reciprocal typification of habitualized actions.”

Institutionalization occurs whenever there is a reciprocal typification of habitualized actions by types of actors. Put differently, any such typification is an institution. What must be stressed is the reciprocity of institutional typifications and the typicality of not only the actions but also the actors in institutions. The typifications of habitualized actions that constitute institutions are always shared ones. They are available to all the members of the particular social group in question, and the institution itself typifies individual actors as well as individual actions.

(Berger and Luckmann 1967, 54)

They go on to discuss how these institutions (such as the constraint to pay attention to time or to carry a mobile phone) are not developed in a power-free situation. Indeed there are forces that urge the social development of these social constructions in one way or in another. The phone companies will want to make us think about making calls, our job will want us to be available, etc. The objectification of these social constructions are the result of our collective actions and they are tempered and adjusted through a whole array of power relations. Thus there is the malleability of the constructionist perspective, the preconfiguration defined by the constraints of the technology and the suggestion that, with time, they will stiffen into social constructions that constrain and direct our behavior.

Other Examples of Taken-for-Granted Technologies

Looking beyond communication technologies, it is possible to see that there are other technologies that function as taken for granted. Mechanical time-keeping and the automobile/suburban housing complex are two examples. It is also instructive to think about well-diffused technologies that do not fulfill these criteria.

As noted, timekeeping has seen this development. The mechanical clock was first developed in the service of Benedictine monks (among others see Zerubavel 1985). As the technology became more robust and portable, mechanical timekeeping diffused through society and in many ways remade social interaction in its own image (for a somewhat strident version of this see Mumford 1934). It gained a central position in society in, for example, the UK in the late medieval period (Glennie and Thrift 2009). As it moved into society it replaced a welter of different timing systems that were, in many cases, based on bells. In a typical city previous to the diffusion of mechanical clocks, different activities were regulated through the position of the sun and quite often by signaling bells. Different institutions, each with their own schedule, would have some system of bell ringing. There were bells for religious gatherings, for civic functions (council meetings, courts, etc.) and for commercial activities. Since each institution had its own set of bells and own schedule there was a confusion of different systems. According to Dohrn-van Rossum, the “acoustic environment” could be surprisingly complex (1992). He reports that Florence had eighty different bells (or more precisely bell sets), each with their own periodicity. If a person were to go to nearby Siena, there was a different set of bells and a different local practice. Mechanical timekeeping simplified this unwieldy system with a single abstract metric that was standard for all.

As mechanical timekeeping became integrated into society, it also engendered a system that legitimized its use. While it can be seen as being stressful (Zerubavel 1985), it is also considered impolite to be late or to waste others’ time (Levine 1998). The use of time is also a social institution. We expect competence in time telling from one another. If we say to one another that we will meet at two thirty, then there is the assumption that each party will understand and respect this decision. Time helps us to mediate social interaction by providing a mechanism through which we can coordinate interaction. Thus, mechanical timekeeping fulfills the notion of being a taken-for-granted technology.

The complex of automobiles and suburban living also, in some cases, fulfills the criteria of being taken for granted. It is clear that for people living in Manhattan or central Paris or London, that is cities where there are well-developed alternatives, a car is not necessary. However, in the vast suburbs of many cities such as those found in Atlanta, Sydney, the areas around Paris and London and of course Los Angeles, it is not reasonable to live without a car. The automobile, of course, has a relatively short history. It is really only in the last half of the twentieth century that there was the intense development of suburbs. In this period, however, the system of automobile-based transportation has altered the development of cities, roads, shopping and a whole array of large and small institutions. In very real ways, this development has changed the social ecology of our lives. We also have developed a range of legitimations for the automobile. We talk about how it gives us freedom of movement, the ability to seek out better opportunities, etc. Finally, it is also taken for granted. In many cities, when we make agreements to meet or to participate in activities, there is also the implicit assumption that the people who are participating will transport themselves with a car. In those cities where there is not a well-developed system of public transportation, not having a car throws the individual on the charity of their friends. This is seen, for example, when elderly people move to sheltered care facilities that are in the fringe areas of the cities. Since this change is also accompanied by losing access to a car, they become isolated from their social ties. Thus, like mechanical timekeeping, the system of suburban living supported by automobile transport has the characteristics of a taken for given system.

One final example of a technology that is widespread but does not fulfill the criteria helps to illustrate the concept. Mechanical refrigeration can be seen as perhaps one of the most significant technical developments of the last 150 years. It has facilitated the preservation of food, changed the quality of the food we eat and has also contributed to the commercialization of food production. Refrigeration in food transport and in grocery stores has changed the variety and the quality of the food we eat. Further, in many countries it is rare not to have a refrigerator in the home.

Refrigeration is also a technology to which we pay little heed. At the same time it is an essential foundation for modern life. In-home refrigeration is widely diffused, it has changed the social ecology and we have a wide variety of legitimations for its use. However, coming back to the idea of social mediation technologies, there is not a sense of reciprocity associated with mechanical refrigeration. With the mobile phone we are somehow failing our friends if we do not have one. If we do not respect time or if we are always the one who needs to be driven we also see the proscriptive tangibility of these technologies. By contrast, if we do not have a refrigerator it does not reverberate through our social circle to the same degree. Thus, it is not an example of a taken-for-granted technology to the same degree as mobile phones, clocks and cars.

Conclusion

It is often commented that mobile telephony and texting in its various forms has established itself in our daily lives. It is a convenient way to stay in touch with one another, to coordinate activities, to reach one another in an emergency or as a way to engage in loose talk.

The system has grown dramatically since the 1990s to the point that it is perhaps the most common type of technology available around the globe. It is possible to call a person in China, Uganda, Haiti as well as Seoul, New York, London or Kinsarvik no matter where they are at the moment. In the developed world, there is often social pressure on the laggards who do not own and use a mobile phone. Their obstinance might be an individual character trait, but it also hinders the smooth functioning of social commerce. The system of making appointments, updating one another and saying in contact has slowly become the province of the mobile phone. Our relationship to the device has made a gradual transition from being something that it “nice to have” to being an integral tie to our social network. We have come to recognize that it is more efficient to have one than not.

Along the way we have developed an ethic that we should be available to one another via the phone. Thus, we do not only have a functional relationship to the device, we have developed a legitimization structure describing its social position. Clearly there are times when we wish it was not that way, but on the whole, we have accepted its role in our lives. Indeed, we demand it of one another.

This has grown to the situation that there is a critical mass of mobile phone and there is a strong legitimation structure. Thus, we have begun to assume them of each other. We assume that we can always call one another to change the time or the place of a meeting. We can send a text to cheer up a sick friend or to ask how they did on their final exam. When they have forgotten their phone or when they are, for whatever reason, not available, the social fabric is torn in some small way. All of this suggests that the mobile phone is a taken for granted form of social mediation. Just as time and timekeeping or the automobile in suburbia is taken for granted, so is the mobile phone.

Beyond being a convenient functionality, we can, in a moral sense, demand them of one another. We, in the sense of the collective social expectations, can ask that a person have a mobile phone, just as we can ask that they pay attention to the time or that they take responsibility to transport themselves in suburbia. The weight of these social expectations comes is not the fault of any particular individual, rather it comes from the interaction of us all working out how to deal with the daily demands we face. The car, the clock and the phone have become three of the technologies that support us in the process of getting to work, agreeing on the location and time of meetings, picking up the kids at school and getting to the store before it closes. At the personal level there is an efficiency that comes from collective adoption. It is easier to coordinate; it is quicker to get in touch, etc. At the same time there are side effects. The suburbanization of society has led to pollution. Clock time leads to stress and this can in turn lead to ulcers and other physical maladies. The mobile phone can have the same impact.5 For better or worse, that is the nature of the situation.

Notes

Sources

Agar, Jon. Constant Touch. A Global History of the Mobile Phone. Cambridge, UK: Icon Books, 2003.

Baron, Naomi. Always On: Language in an Online and Mobile World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Berger, Peter, and Thomas Luckmann. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Anchor, 1967.

Briscoe, Bob, Andrew Odlyzko and Benjamin Tilly. “Metcalfe’s Law is Wrong—Communications Networks Increase in Value as They Add Members—But by How Much?” IEEE Spectrum. no. 7 (2006): 34–39.

Campbell, Scott, and Tracy Russo. “The Social Construction of Mobile Telephony: An Application of the Social Influence Model to Perceptions and Uses of Mobile Phones within Personal Communication Networks.” Communication Monographs. no. 4 (2003): 317–334. DOI:10.1080/0363775032000179124.

Dohrn-van Rossum, Gerhard. History of the Hour: Clocks and Modern Temporal Orders. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Dugan, Maeve. “Cell Phone Activities.” Pew Research Center. September 16, 2013. Accessed November 1 2013. www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media//Files/Reports/2013/PIP_CellPhoneActivitiesMay2013.pdf

Durkheim, Émile. The Rules of the Sociological Method. New York: Free Press, 1938.

Dutwin, David, Scott Keeter and Courtney Kennedy. “Bias from Wireless Substitution in Surveys of Hispanics.” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. no. 2 (2010): 309–328.

Economides, Nicholas, and Charles Himmelberg. “Critical Mass and Network Evolution in Telecommunications.” In Toward a Competitive Telecommunication Industry, edited by Gerald W. Brock, 47–64. Mahwah, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum, 1995.

Gilbert, Margaret. On Social Facts. London: Routledge, 1989.

Glennie, Paul, and Nigel Thrift. Shaping the Day: A History of Timekeeping in England and Wales 1300—1800. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Haddon, Leslie. “Domestication and Mobile Telephony.” In Machines That Become Us, edited by James E. Katz, 43–56. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 2003.

Johannesen, S. Sammendrag av markedsundersøkelser gjennomført for televerket i tiden 1966—1981. Kjeller: Televerkets Forskninginstitutt, 1981.

Lenhart, Amanda. “Teens, Smartphones & Texting.” Pew Internet & American Life Project. March 19, 2012. Accessed February 3 2014. wwww.pewinternet.com/~/media/Files/Reports/2012/PIP_Teens_Smartphones_and_Texting.pdf

Lenhart, Amanda, Rich Ling, Scott Campbell and Kristen Purcell. “Teens and Mobile Phones.” Pew Research Center. 2010. Accessed November 15 2012. http://www.pewinternet.org/2010/04/20/teens-and-mobile-phones/

Levine, Robert. A Geography of Time: The Temporal Misadventures of a Social Psychologist, or How Every Culture Keeps Time Just a Little Bit Differently. New York: Basic, 1998.

Licoppe, Christian. “Connected Presence: The Emergence of a New Repertoire for Managing Social Relationships in a Changing Communications Technoscape.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space. no. 1 (2004): 135–156.

Ling, Rich. The Mobile Connection: The Cell Phone’s Impact on Society. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufman, 2004.

Ling, Rich. Taken for Grantedness: The Embedding of Mobile Communication into Society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012.

Ling, Rich, and Geoff Canright. “Perceived Critical Adoption Transitions and Technologies of Social Mediation.” Paper presented at The Cell and Self Conference in Ann Arbor, Michigan, 2013.

Ling, Rich, and Jonathan Donner. Mobile Communication. London: Polity, 2009.

Ling, Rich, Troels Fibæk Bertel and Pål Roe Sundsøy. “The Socio-Demographics of Texting: An Analysis of Traffic Data.” New Media & Society. no. 2 (2012): 280–297.

MacKenzie, Donald, and Judy Wajcman. The Social Shaping of Technology: How the Refrigerator Got Its Hum. Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1985.

Markus, Lynne. “Toward a “Critical Mass” Theory of interactive Media: Universal Access, Interdependence and Diffusion.” Communication Research. no. 5 (1987): 491–511.

Metcalfe, R. “Metcalfe’s Law: A Network Becomes More Valuable as It Reaches More Users.” Infoworld. no. 40 (1995): 53–54.

Mumford, Lewis. Technics and Civilization. San Diego: Harvest, 1934.

Rogers, Everett. Diffusion of Innovations. New York: The Free Press, 1995.

Sawhney, Harmeet. “Wi-Fi Networks and the Reorganization of Wireline–Wireless Relationship.” In Mobile Communications: Re-Negotiation of the Social Sphere, edited by Ling and Pedersen, 45–61. London: Springer, 2005.

Schroeder, Ralph. Rethinking Science, Technology and Social Change. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

Silverstone, Roger, and L. Haddon. “Design and the Domestication of Information and Communication Technologies: Technical Change and Everyday Life.” In Communication by Design: The Politics of Information and Communication Technologies, edited by Silverstone and Mansell, 44–74. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Silverstone, Roger, and Eric Hirsch. Consuming Technologies. London: Routledge, 1992.

Skelton, C., T. Lynch, C. Donaldson and M. Lyons. Modelling Product Life Cycles from Customer Choice. Ipswich: British Telecommunications Laboratories, 1995.

Walton, M., and J. Donner. “Read-Write-Erase: Mobile-mediated Publics in South Africa’s 2009 Elections.” In Mobile Communication: Dimensions of Social Policy, edited by James E. Katz, 117–132. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2011.

Weber, Max. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Routledge, 1930.

Zerubavel, Eviatar. Hidden Rhythms: Schedules and Calendars in Social Life. Berkeley: University of California, 1985.